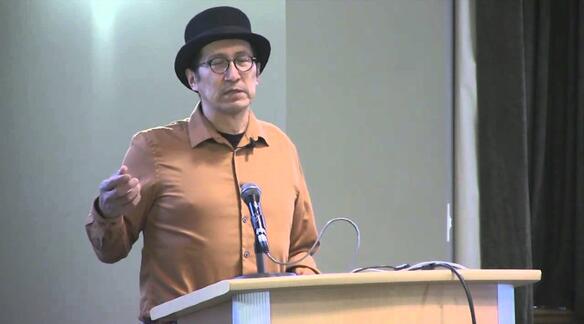

Richard Wagamese (1955-2017) was one of Canada’s foremost writers, and one of the leading indigenous writers in North America. He was the author of several acclaimed memoirs and more than a dozen novels, including Indian Horse, Medicine Walk, and Dream Wheels. Indian Horse was the People’s Choice winner of the national Canada Reads competition in 2013, and its film made its world premiere at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival. Wagamese began his career in 1979 as a journalist and worked as a newspaper columnist and reporter, radio and television broadcaster and producer, and documentary producer—both individual works and his body of work have been celebrated with numerous awards, including the George Ryga Award for Social Awareness in Literature, the Canadian Authors Association Award for Fiction, and the Matt Cohen Award in Celebration of a Writing Life. Wagamese was honored with Honorary Doctor of Letters degrees from Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops and Lakehead University Bay. He lived in Kamloops, British Columbia.