Excerpts: Dear Memory, For Joshua, Peyakow, & Saga Boy

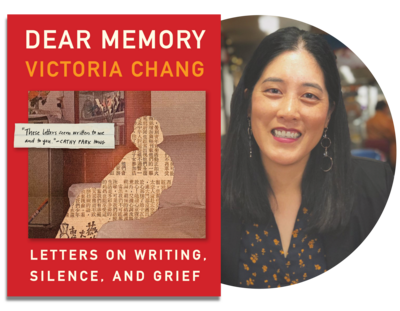

Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief by Victoria Chang

Dear Mother,

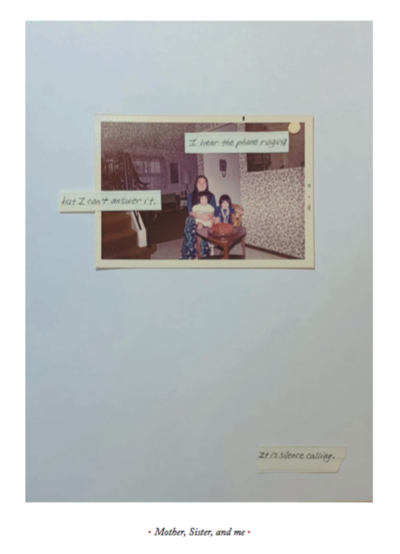

I have so many questions. What city were you born in? What was your American birthday? Your Chinese birthday? What did your mother do? What did your grandmother do? Who was your father, grandfather? It’s too late now. But I would like to know.

I would like to know why your mother followed Chiang Kai-shek, taking you and your six (or seven?) siblings across China to Taiwan. I would like to know what was said in the planning meeting. I would like to know who was in that meeting. Where that meeting took place.

I would like to know the people who were left behind. I would like to know if there are other people who look like me.

I would like to know if you took a train. If you walked. If you had pockets in your dress. If you wore pants. If your hand was in a st, if you held a small stone. I would like to know if you thought the trees were black or green at night, if it was cold enough to see your breath, to sting your ngers. I would like to know who you spoke to along the way. If you had some preserved salty plums, which we both love, in your pocket.

I would like to know if you carried a bag. If you had a book in your bag. I would like to know where you got your food for the trip. Why I never knew your mother, father, or your siblings. I would like to have known your father. I would like to know what his voice sounded like. If it was brittle or pale. If it was blue or red. I would like to know the sound he made when he swallowed food.

I would like to know if your mother was afraid. During college, I spent several weeks with her in Taiwan. She bought me bao zi, buns, every morning—the bao that steamed in small plastic bags with no ties, and sweet dou jiang, tofu milk. Always too hot for me to drink. She sat there and watched me eat, complained to me about your brother’s wife. Complained of being sick and how no one would help her.

Do you know how long it took me to gure out how to call an ambulance? And then when they came, she refused to go. I still remember how the two men stared at me, as if I could move a country.

Listen. It’s the wind. at’s the same wind from your countries. Sometimes if I listen closely at night, I can hear you drop a small bag at the door. I hear the sound of the bao touching the ground and the wind trying to open the bag.

But when I open the door, there’s nothing there. Just the same wind. ousands of years old. Happy birthday, wind. Happy birthday, Mother. April 6, 1940. I know this now. All the nurses, doctors, and morticians asked me, so I memorized it, your American birthday. April 6, 1940, I said again and again. As if I had known this my whole life.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

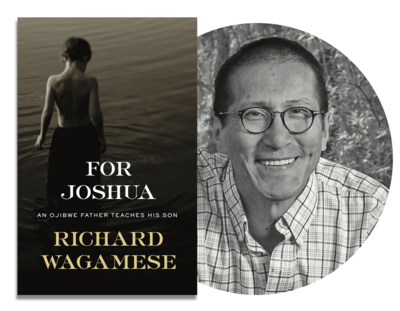

For Joshua: An Ojibwe Father Teaches His Son by Richard Wagamese

Drinking is why we are separated.

That’s the plain and simple truth of it. I was a drunk and never faced the truth about myself—that I was a drunk. Booze owned me. I offered myself to it when I was a young man and it was only too glad to accept me into the ranks of its worshippers, the ones who are willing to pay with everything for one more round. I drank because it made things disappear. ings like shyness, inadequacy, low self- worth—and fear. I drank out of the fears I’d carried all my life, the fears I could never tell anyone about, the fears that ate away at me constantly, even in the happiest moments of my life, and your mother did the only thing that she knew to do and that was to take you away where you could be safe. I don’t blame her for that. I’m thankful in fact. I drank on and off, like I’d done all my life, and your mother grew tired of my constantly returning to the bottle. She refused to let me see you. When I nally got sober I knew I had responsibilities, but by then we’d been apart more than two years. is book is my way of living up to some of that responsibility.

As Ojibwe men, we are taught that it is the father’s responsibility to introduce our children to the world. In the old traditional way, an Ojibwe man would take his child with him on his journeys along the trap lines, on hunting trips, shing, or just on long rambles across the land. The father would point out the things he saw on those outings and tell his child the name of everything he saw, explain its function, its place in Creation. Even though the child was an infant and incapable of understanding, the traditional man would do this thing. He would explain that the child was a brother or a sister to everything and that there was no need to fear anything because they were all relationse father would perform this ritual so the child would feel that it belonged. He would do this so that the child would never feel separated from the heartbeat of Mother Earth. So that children would always feel that heartbeat in the soles of their feet. He would do it so that kinship was one of the rst teachings the child received. The father would do this to honour the ancient ways that taught us that we are all, animate and inanimate alike, living on the one pure breath with which the Creator gave life to the Universe.

And he did it for himself.

He performed this task so he could learn that devotion is a duty driven by love, one which has its beginnings in the earliest stage of life, and that teaching, preparing a child for the world, begins then as well.

This book is my way of performing that traditional duty. I do not know if or when we will be together. Because of the way I chose to live my life, the price we’ve paid is separation. I am neither a hunter nor a trapper. I am not a teacher, healer, drummer, singer, or dancer. Nor am I a wise man. But I offer this book as a means of fulflling that traditional responsibility. I want to introduce you to the world, to Creation, to the landscape I have walked, to some of the people who have shaped my life. All I have to offer is all that I have seen, all the varied people I became, and maybe you will glean from all of it an idea of the father that my life and my choices have denied you.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

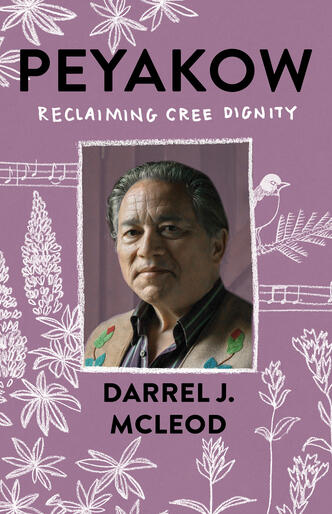

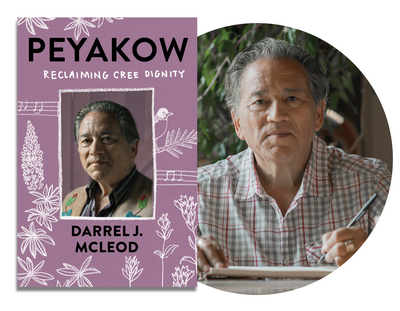

Peyakow: Reclaiming Cree Dignity by Darrel J. McLeod

That afternoon, I strolled to the cemetery at the edge of town and paused beside the white picket fence around one grave. I looked toward Shass Mountain and began to pray—not to Jesus or to God, but to the ancestors of this place. I asked them to accept me, to protect me and guide me to do the best I could to help their descendants.

At two in the morning in a cabin along the shores of Stuart Lake, I woke with a sucking hollowness in my chest. Was I really going to do this—move north on my own, leaving my teaching job and friends in Vancouver? More importantly, was I going to leave Milan? When the emptiness didn’t recede, I lay in the dark, thinking. I pictured my classroom at Trafalgar Elementary, on the west side of Vancouver, and wondered how my students would have reacted had they seen Yekooche, the school building and the students—the beauty, the starkness, the unkemptness and the abject poverty. I thought about the contrast between my well- equipped and neatly organized classroom, tastefully decorated with student art, and what I had seen at the Portage School. I would have to get rid of everything but the furniture and start anew. What would we do for phys. ed.? There was no gym or even a playground. I would have to recruit an entirely new team of teachers, and that wouldn’t be easy. The next day I would need to start ordering books and poring over résumés.

I tried to lull myself to sleep by picturing Milan’s bulky hands and his kind, loving gaze. Milan had purchased a trendy condominium in Kitsilano, where we had settled into a comfort- able life with a circle of caring friends, the type of friends I could only have dreamed of having in northern Alberta or in Calgary— teachers, a school principal, a physiotherapist, a Guatemalan friend and one who was Rotuman. Weekly dinner parties. Weekend mornings at Granville Island Public Market enjoying coffee and croissants while we listened to buskers were followed by hours of me singing my favourite tunes and accompanying myself on piano or guitar at home. Surely Milan would stick with me through the transition to working and living in Yekooche. He had been so supportive in my university years, through my five years of teaching and through my sorrow when first my sister Debbie died, and then Mother.

Why was I making this drastic change in my life? Was I trying to rebuild my connection with Cree culture after losing my only bridge to it—Mother? Was I trying to get back to my roots, or was it simply more escapism, a distraction to avoid my predicament—a collapsed and diminishing family, sexual confusion, an uncertain future, a constant fear of falling into a downward spiral and losing everything?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

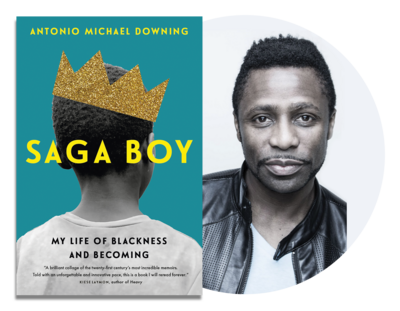

Saga Boy: My Life of Blackness and Becoming by Antonio Michael Downing

Chapter One

MONKEYTOWN

I

Poulourie was my everything.

Pou-lour-ree. These three delicious syllables ruled my life. I was five, and if I ever got my hands on as little as fifteen cents, I would buy poulourie, a fluffy, golden deep-fried ball of dough that was crunchy on the outside and chewy on the inside. I lived in New Grant, a village in the south of Trinidad—or “down South,” as we would say. It sat between wide, muddy rivers full of crocodiles, thick tropical wilderness, and fields upon fields of sugar cane. The yellow-and- brown two-storey building where we learned was called New Grant Anglican School, and it had been established in the year 1900. To the front, there was a paved asphalt area where we played netball, rounders, and hopscotch in our neat uniforms. In the field next to that, we dashed about, made believe, and whenever possible, yelled as loudly as we could.

Next to this field was a small shop of wonders. They sold: pickled red mango, coconut sugar cakes, sticky peppery anchar, and of course, poulourie. It was pretty much neutral in taste, but it was served with spicy mango chutney or sticky sweet tamarind sauce on brown wax paper. Poulourie was my favorite thing.

One day, I had bought three or four and was fixated on inhaling them while waiting to cross the main road. I was straining not to get any chutney on my khaki uniform. Cars roared by while I stood, my mouth wet with wanting. I was captivated by the mesh pattern inside the dough balls, by the heat of the wax paper and the green mango chutney. Just as I looked up, a twenty-seat maxi taxi passenger van dashed right by my nose. My nostrils burned with diesel. A drunk on the other side of the road staggered backwards, his eyes bulging big, like guavas.

“Yuh go get kill one day!”

In Trini, an alcoholic was a “rumbo.” Everybody drank rum, and I knew from the way big people talked that you never listened to a rumbo.

Still, I finished my poulourie, which was never “poulouries” even if you had several, and looked both ways before crossing to my street: Monkeytown Road, Third Branch. Which at this point was the only place in the universe I knew.

II

On a day like that, it would have been normal to hear the sound of Miss Excelly’s voice drifting over the tombstones. There was a cemetery on either side of the street, and ours was the first house after the one on the left. Her voice would catch me as soon as I left the junction, drifting like a breeze.

My grandma—we called her Mama, and everyone else called her Miss Excelly—was always singing. When she woke up with the kiskadees, when she was happy and smiling, when she was thoughtful and laughing to herself, or when she went to bed, the bullfrogs as her backup, she sang. Hymns, mostly. About Jesus and salvation and redemption and power. So basically every single song in the Anglican hymnal. “Power in the Blood,” “How Great Thou Art,” “Rock of Ages,” “Abide with Me,” and the draggy one that was her favourite, “Stars in My Crown” which I didn’t really understand then, except I knew it had something to do with getting “stars in my crown … when at evening the sun goeth down … in the mansions of rest.”

What I did know was that her bright eyes and soft face got very strange when she sang this hymn. She would smile with her whole face but have tears in her eyes. Was it possible to be sad and happy at once?

In those moments coming home from school, the world seemed dim and out of focus. Everything hushed. Her voice perfumed the very air. The tall grass across the cemetery leaned in slow motion. Beads of sweat slid down my forehead and tickled my neck. All of creation became her voice calling me home.