5 Reasons to Teach This Book: The Blue Sky

Welcome, friends, to the latest installment of 5 Reasons to Teach This Book! In this interview series, we examine what we can learn from Milkweed’s titles by discussing our books with educators, authors, and booksellers. This month, we’re featuring The Blue Sky, a novel that originally joined our catalogue in 2006 but will be reissued this summer as part of the Seedbank series.

The Blue Sky is a tale of family—blood and found—and the distances we travel to preserve our chosen bonds. In fictionalizing his own childhood, author Galsan Tschinag walks readers through the familiar and anxious space between childhood and adulthood, as well as making tangible the distinct ache of a culture forced to fade. I haven’t read a book as rich with love in quite some time; nor have I felt so keenly another’s loss.

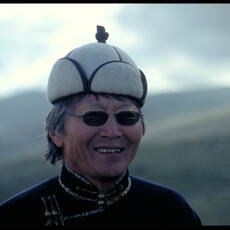

I was thrilled to get in touch with Katharina Rout, the author, educator, and translator responsible for making this book accessible to English-language readers. Aside from being (as I learned in our exchange) a praiseworthy grower of spinach, she’s also—unsurprisingly—a fantastic resource for better understanding the intricacies of literary translation. What happens to a character’s voice when it crosses into another language? What do we stand to learn from the nomadic Tuvan people’s way of life? The answers to these questions—and more—lie below.

Bailey Hutchinson: One of my favorite things about The Blue Sky is how the text manages to balance the voice of a young Tschinag—urgent with love and attachment—with deft prose, capturing at once the perspective of a child and the composition of an older, wiser eye. How did you go about maintaining that balance in translation?

Katharina Rout: An earlier version of the novel offered more of the adult’s perspective, whereas in the novel’s final version the child’s voice dominates. The novel gained greater immediacy and emotional power as a result. We are drawn so much into the child’s experience of the world that we might be forgiven if we overlook the wisdom of the narrator who knows that our young hero’s world is about to shatter. For the balance you mention it was crucial that the language remained consistently concrete and the tone non-judgmental and warm. At no point does the more mature voice claim superiority.

The brilliance of the novel’s composition comes not least from the fact that we barely notice how well constructed it is. We feel invited to listen to a storyteller but read a carefully crafted coming-of-age novel. Of course, that is the author’s achievement and not anything the translator can take credit for.

Bailey Hutchinson: There’s a temptation to think of the world of a book as not-our-reality, even in works of nonfiction; one may think a story or person too far removed from their own place or time or lived experience to be relevant, but The Blue Sky proves quite the opposite. “When the sky was involved, we were not allowed to lie,” Tschinag writes, and I think this speaks to a sort of universally recognizable earnestness in the book. What other big truths does The Blue Sky carry?

Katharina Rout: Many of the book’s truths are universal because regardless of where we grow up, we learn about love and trust and caring in our families, much like Dshurukuwaa. When we are little, the adults in our lives are huge and powerful, as are Dshurukuwaa’s parents and grandmother, and we long for agency and have dreams for our future, as does our young protagonist. But then we discover that our parents are not omnipotent or infallible and cannot protect us from great losses and despair. Gradually, we develop a sense of the burdens of adulthood and the potential of material wealth and greed to sow disharmony in our families and neighborhoods and to destroy our precious natural resources (such as the trees, for example, that Tuvans feel so strongly about protecting that they have created a taboo on cutting them). We learn that we and our loved ones are mortal. And in the face of these experiences, we develop a deeper appreciation for the kindness and love we can share, for the resilience we can develop in the face of painful change, and for the planet’s gifts we are sustained by.

Bailey Hutchinson: There are, of course, so many different ways to learn from this book, but I’m especially interested in the impact The Blue Sky has on The Reader vs. The Writer. As an instructor, what would you hope to guide each “type” of student towards noticing in the book?

Katharina Rout: In my experience, students learn best how to read if they also write, and vice versa.

For example, they could be asked to tell the story, or parts thereof, in the voice of the father, the mother, or the grandmother. Each version would have to be mostly a pastiche made up of the character’s direct speech in the book. Another exercise would ask students to collect all the sayings the characters quote in the novel. These sayings refer not only to customs and practical necessities but also to appropriate ways of talking, as in “People rarely meet with their death because of a horse but often because of a mouth” (36). Students would then rearrange the collection of sayings and create additional ones in the same style to write about the social values embedded in the novel, something like A Tuvan Art of Living. In a similar exercise, they could create a manual for herders. Or they could take a particular scene in the book and describe a similar scene in their own family, focusing especially on the similarities and differences in the emotional interactions and verbal exchanges.

There are many possible variations to these exercises, but they all intimately connect reading and writing.

Bailey Hutchinson: A friend once told me that a good translator approaches every book as though it is written in a language of its own. What is it like for you navigating larger conventions of literature written in German alongside the unique world of The Blue Sky?

Katharina Rout: Your friend’s excellent point is particularly true of The Blue Sky, which really is written in a language of its own. The memories of its author, Galsan Tschinag, and the experiences of his fictional alter ego and his family are rooted in the Tuvan culture from a time when the Tuvan language was exclusively oral. As the narrator tells us in The Blue Sky, letters did not exist, and language travelled “from mouth to ear” (22). Concepts such as “bringing up” a child did not exist, either (22). In order to write about his childhood, the author first had to translate his oral experience in Tuvan into a written language, possibly Mongolian or Kazakh (the two languages he grew up with in addition to Tuvan), before he also learned Russian in school.

But while Tschinag has published fiction in Mongolian, the language he prefers to write in is German. It was during his studies in East Germany in the 1960s that Tschinag became a writer. He admires some of the greatest German writers, such as Goethe, whom he considers a shaman, credits the East German writer Erwin Strittmatter as his mentor, and after his return to Mongolia translated German literature into Mongolian. But he also loves much of Russian literature, especially Lermontov, and feels a literary kinship with the Kyrgyz author Chinghiz Aitmatov. Seeing his work only within the context of German literature would miss the enormous importance of the Tuvan oral tradition. Tschinag has always emphasized that he wants to tell not simply his own story but the stories of his people so they won’t be forgotten should his minority culture disappear from history, as he fears it will.

When Tschinag first encountered German, he was startled by its sharp, hissing sounds, which struck him as being hard like German buildings and much else in German culture. By contrast, he says, Tuvan sounds are as round and soft as the felted yurts his people live in. In his writings, he has in effect created a hybrid German that is sprinkled with Tuvan, Kazakh, and Mongolian words, with anachronisms and neologisms, and that echoes the patterns of oral storytelling. At times, he draws on the old epics and their stylistic devices, at other times on shamanic chants. For Tschinag, who is a shaman and by his people is referred to as “the singer,” words can have almost magic qualities and are his means of communicating with the spiritual world. But most often, in The Blue Sky, he evokes the daily, intimate conversations in the family yurt.

Knowing German literature was not sufficient for me to translate this book. I had to learn much about the reality depicted in it. For example, we are told on the first page where to put bad dreams. I struggled with how to translate the German word for the emptiness (“Leere”) we were to send our dreams to. Into what void? What absence? I sent my question–and many similar ones—to the author. You must come to the Altai, he wrote back. Then you will find out. And so I went. Tschinag showed me much but waited before addressing my questions. One day on the steppe, he pointed at the burrows of marmots or mice. That’s where you put the bad dreams! The emptiness I had wondered about became “a hole in the ground” in my translation.

Bailey Hutchinson: What other books would be listed under the Required Reading section of The Blue Sky’s syllabus?

Katharina Rout: The Blue Sky can be part of many different syllabi, from young-adult coming-of-age stories to reading lists in anthropology courses on pastoralism or history courses on the Soviet Union’s influence on ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union and its satellite states. It beautifully fits into syllabi of Indigenous writings about contact and colonization. A high school syllabus might pair it with As Long as the Rivers Flow (2005) by Larry Loyie and Constance Brissenden, the story of a young Cree boy that contrasts the traditional education provided by his Cree community and the residential school he and other children have to attend, much as do Dshurukuwaa’s siblings in The Blue Sky. Readers of any age may want to read The Blue Sky together with Chinghiz Aitmatov’s stories or novels. Or they may turn to the books by the great Yuri Rytkheu about the Chukchi people, who, like the Tuvans, have wisdom to share with us as they survive the threats to their culture and natural environment.