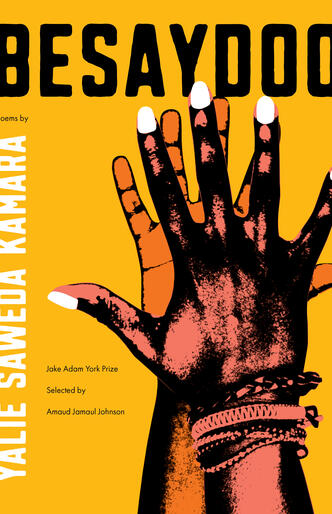

On Yalie Saweda Kamara’s Besaydoo: a monument to multiplicity (and home)

As an Afro-Latina American citizen, I tend to seek stories that center voices, cultures, experiences, and lifeways historically peripheralized by the Western literary canon. But for all the breadth that I encounter still with every new BIPOC-authored book I read, I am routinely enchanted by a sense of what remains familiar. What lands have you been denied, what spaces have you been neglected in—and rejected from—and from what sunless places were you forced to grow? I ponder these questions as I read, acutely aware of the ways longing for BIPOC authors so often manifests on the page as a reaching toward home. It is a feeling as familiar to me as home itself, and Yalie Saweda Kamara’s stunning debut collection of poems, Besaydoo, is no exception to this rule. In her elegantly wrought love song for diasporic peoples and places in this country and beyond, Kamara renders a touchstone for all those still wandering in search of a home to call their own. So, too, does she render an invitation to find yourself at home anywhere you know: in the faces of loved ones, in the scents of a city, in the sacred consonants of your very own name.

Kamara’s collection aptly begins with a poem called “Oakland as Home, Home as Myth.” With its powerful opening line, “Oakland is a killing field, they say,” Kamara reframes stereotype as mythology. And in subsequent lines blooming between this staggered refrain, she wrenches her beloved city from the grips of stigma, illuminating the intimate olfactory experiences that come not from merely visiting a place, but from living and loving and existing within it. “What if, in this story of trickling blood, there is no gun, but instead a finger / pricked by a blackberry bush on Thornhill Drive?” Kamara asks. In these lines and elsewhere in her poems, beauty abounds and persists, resisting against the tension of prescriptive labels carelessly crafted by the kinds of “outsiders” who feel most at home within their own assumptions. Still, Kamara is nothing if not a clear-eyed storyteller; she does not shy away from a negative reputation, nor does she seek to make her ode a new kind of revisionist mythology: “Land of dirty concrete and sunshine. Land of the slain and the ever rising. Land of / Tom Hanks and bullets. Land of Slideshows and Market Hall. Land of Chow Mein and / pine trees. It’s true, our contradictions are dizzying.”

From reclaimed portraits of Oakland, California, and Bloomington, Indiana, to a biography of the author’s name, to love letters for Gabby Douglas and a powerful vision of “New America,” Kamara’s poems don’t just reach far and wide—they run deep. But perhaps the truest gift of Besaydoo is its ability to always connect the endless griefs of existence back to fierce, unwavering (Black) joy. In the white space between every line, I read the joy of a poet who has learned that the elegy and the ode are two sides of the same coin. It is the joy of a woman who has called multiple people, places, languages, and religions “home,” and the joy of a culture-bearer whose every stanza is an invitation to “Yes…mourn, but…celebrate too.” I gratefully accept her invitation, and I hope you will too; for our multitudes and multiplicities are beyond cause for celebration—they are cause, too, to make ourselves perfectly at home.

Besaydoo

While sipping coffee in my mother’s Toyota, we hear the birdcall of two teenage boys

in the parking lot: Aiight, one says, Besaydoo, the other returns, as they reach

for each other. Their cupped handshake pops like the first, fat, firecrackers of summer,

their fingers shimmy as if they’re solving a Rubik’s cube just beyond our sight. Moments

later, their Schwinns head in opposite directions. My mother turns to me, revealing the

milky, John-Waters-mustache-thin foam on her upper lip, Wetin dem bin say?

Besaydoo? Nar English? she asks, tickled by this tangle of new language. Alright.

Be safe dude, I pull apart each syllable like string cheese for her. Oh yah, dem nar real padi,

she smiles, surprisingly broken by the tenderness expressed by what half my family might call

thugs. Besaydoo. Besaydoo. Besaydoo, we chirp in the car, then nightly into our phones

after I leave California. Besaydoo, she says as she softly muffles the rattling of my bones

in newfound sobriety. Besaydoo, I say years later, her response made raspy by an oxygen

treatment at the ER. Besaydoo, we whisper to each other across the country. Like

some word from deep in a somewhere too newborn-pure for the outdoors, but we

saw those two boys do it, in broad daylight, under a decadent, ruinous, sun.