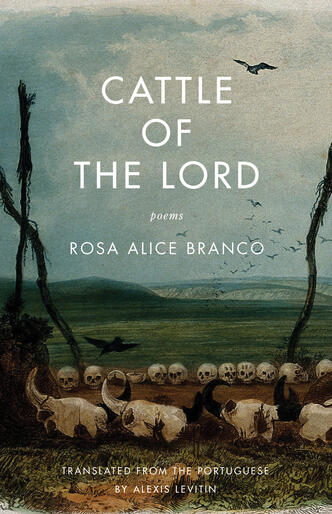

Rosa Alice Branco is the prizewinning author of Cattle of the Lord, translated by Alexis Levitin. She is one of today’s premier Portuguese-language poets, with over ten collections of poems translated and published around the world. The English translations of her work, developed in collaboration with renowned translator Alexis Levitin, have been featured in New European Poets and dozens of magazines and journals in the United States, including The New England Review, Prairie Schooner, and Words Without Borders. Branco has received the Espiral Maior Poetry Prize for Best Collection in Brazil, Portugal, Angola, and Galicia. Originally from Aviero, she now lives in Porto, where she is a Professor of the Theory of Perception at the city’s Institute of Art and Design.