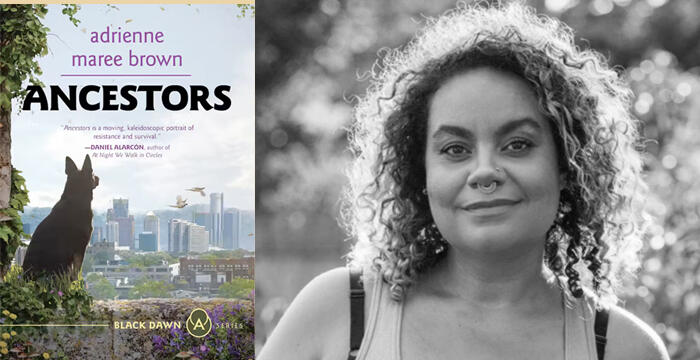

adrienne maree brown : Ancestors

With the arrival of Ancestors, the third and final book in adrienne maree brown’s Grievers Trilogy, we take the iconic frames she has created in her nonfiction work—emergent strategy, pleasure activism, fractal responsibility, loving corrections and more—and look at how they are dramatized within this fictional near-future Detroit. Much as the three books do themselves, one to the next, we look at questions of care and solidarity at three different scales—the individual, the interpersonal, and the collective—and we explore how they relate to each other fractally, both within this imagined world, and within our own. We conjure the work and thought of everyone from Ursula K. Le Guin to Octavia Butler, Grace Lee Boggs to Saul Williams, Toni Morrison to Toni Cade Bambara, as we explore everything from the allure and dangers of utopias, to how to knit oneself into a larger collective as part of dreaming an otherwise.

adrienne’s first appearance on the show was for the 2022 series Crafting with Ursula, where we looked at questions of social justice and science fiction in adrienne’s work alongside that of Ursula K. Le Guin.

For the bonus audio archive, adrienne contributes the singing of two songs from the Grievers trilogy. This joins bonus audio from many other past guests, including Dionne Brand, Christina Sharpe, N.K. Jemisin, Daniel José Older and more. The bonus audio is only one of many things to choose from if you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. Find out more at the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today’s conversation.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you in part by Brilliant: The Art of Literary Radiance by Jenny Forrester. Forrester's writing instruction manual and manifesto is a call to tell a story for your own sake and for others. Art as activism, the personal as political. Brilliant is more than craft, more than memoir; it's prophecy, resistance, transformation. Forester invites you to dismantle the narratives that oppress and to build the ones that liberate, to write as witness, to write as revolution, to write not just beautifully, but meaningfully. Whether you're a poet, a novelist, a truth teller, or an experimentalist, this book is your companion, your catalyst, your call to the page, radically personal, fiercely political, fearlessly radiant. Brilliant: The Art of Literary Radiance is available now at powells.com or by contacting the author directly at the email jenny@theforrest.org. Write like the world depends on it. Today's episode is also brought to you by There Are Reasons for This by Nini Berndt. A stunning novel that, in the words of Kristen Arnett, is messy, beautiful, gorgeous, and compelling. When Lucy arrives in Denver in search of Helen, the woman her recently dead brother loved, she finds nothing is as she expected. The city is crumbling, the weather is tempestuous, and she’s increasingly obsessed with Helen, who has no idea who Lucy truly is. Called haunting and incantatory by Kimberly King Parsons, There Are Reasons for This is a modern love song about the fallibility of love in all its iterations, about the denial and tethering of desire, about the family we are given and the one we find for ourselves. To what comes next, whatever that may be. There Are Reasons for This is available now from Tin House. Before we begin today’s conversation with Adrienne Maree Brown, I want to say a couple of things about voice. First, my voice in this conversation, which longtime listeners are going to notice is unusually and inexplicably low, you might think I have a cold. No. You might think I have allergies. Not the case. I even stop at the beginning as I’m introducing her, marveling at how I sound to myself, and say outside the interview, “Let me drink some water to clear the frogginess out of my voice,” but to no avail. Our conversation is about, among many other things, cross-species solidarity and cross-species ritual magic. So perhaps the frogs are indeed insisting on their presence. I can’t say. Or maybe it’s a second puberty, as I did think about chanting my Torah portion at my bar mitzvah, not knowing which of my two voices—the old or the new—would come out. But what was even more uncanny than hearing one’s own voice as other, was at the very end of our conversation, having just talked about ancestors and ancestral spirits, I asked Adrienne to read a poem and quite suddenly, as she gets ready to begin, her voice becomes really different and for a moment she isn’t sure she can proceed and she says something like, “Just so you know, when I talk about ancestors, they get up all in my throat.” So puberty, frogs, or ancestors, something was going on, not just for me, but for both of us. And staying with the theme of voices, even if we didn’t talk at length about songs and singing in this conversation, it would be a special thing that for the bonus audio archive, Adrienne sings two of the songs in the Grievers Trilogy. But after you hear our discussion about songs, you'll see even more how special it is that she contributed this to the archive. And strangely, while most of the bonus audio archive is readings, some craft talks, some writing prompts, and some translation interviews, lately, people have been contributing songs—whether Leanne Betasamosake Simpson giving us a sneak peek of her upcoming album, or two past guests of the show, Dao Strom and Alicia Jo Rabins, who have since collaborated on an EP that they released this year, sharing two tracks from it—the bonus audio is only one of many things to choose from when you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. And no matter what you choose, every supporter gets resources with each and every conversation and is invited to join our collective brainstorm of who to invite into the future. You can check it all out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today’s episode with Adrienne Maree Brown.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning, and welcome to Between the Covers. I’m David Naimon, your host. Today’s guest writer, Adrienne Maree Brown, has been many things—from a doula to a social justice facilitator to the author of many books, including Emergent Strategy, Pleasure Activism, We Will Not Cancel Us and Other Dreams of Transformative Justice, and Holding Change. Emergent Strategy, both the book and the practice, looks to science—to emergent patterns in the non-human, plant, and animal worlds—as models for adaptation and inspiration, and also to science fiction, particularly the philosophy of change in the works of Octavia Butler. Brown, along with Alexis Pauline Gumbs, published the Octavia Butler Strategic Reader. She’s run a series of Octavia Butler–based science fiction writing workshops, and she collaborated with Walidah Imarisha and Sheree Renée Thomas on the anthology Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements, which contains writings from one from LeVar Burton to Mumia Abu-Jamal. Adrienne Maree Brown is also a podcaster, co-host of Octavia’s Parables, a deep dive into Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, as well as the co-host of the podcast How to Survive the End of the World with her sister Autumn Brown. As if that were not enough, Adrienne is also a writer of science fiction herself. She attended the Clarion Sci Fi Writers’ Workshop and Voices of Our Nations in the inaugural cohort for their speculative fiction workshop. She was the 2015 Ursula K. Le Guin Feminist Science Fiction Fellow at the University of Oregon Special Collections Library and Archives, which houses the papers of key feminist science fiction authors including Joanna Russ, Molly Gloss, James Tiptree Jr., and Ursula K. Le Guin herself. Brown’s first appearance on Between the Covers was in 2022 as part of the “Crafting with Ursula” series, where we looked at the relationship between science fiction and social justice, between the imagination and organizing, in both Le Guin’s work and Brown’s work side by side. Since then, she has published Fables and Spells: Collected and New Short Fiction and Poetry, and Loving Corrections, where she brings her writings on belonging and accountability into a generative space, a loving corrections frame, where rehearsals for the revolution become the everyday norm in relating to one another. But the reason for Adrienne’s return today is because the year before we first talked was Adrienne’s fiction debut with the book Grievers, a book that inaugurated AK Press’ Black Dawn series, which aims to foreground the values of anti-racism, feminism, anti-colonialism, and anti-capitalism, as well as centering queerness, Blackness, and anti-fascism. Grievers was met with critical acclaim and was followed by the book Maroons, both receiving starred reviews by Publishers Weekly. The occasion of our conversation today is the arrival of the third and final book in the Grievers Trilogy called Ancestors. Michigan poet laureate Nandi Comer says of this book, "This post-industrial, post-pandemic, post-apocalyptic novel examines the collective struggle for harmony in the face of personal and collective trauma. ... Ancestors delivers tender conjecture full of somatic healing, spiritual fortitude, and human re-connection. This is the book we need." Welcome back to Between the Covers, Adrienne Maree Brown.

Adrienne Maree Brown: Thank you, David. You're one of my favorite people to have shared a bio. I'm always like, "I'm doing great at life when you introduce me." [laughter]

DN: Well, one thing that is really great about discussing your trilogy as a trilogy—looking at the movement between Grievers, Maroons, and Ancestors, and what that movement across books might teach us—is that it gives us a chance to look at the ways many of your ideas in nonfiction, whether Emergent Strategy or Pleasure Activism or Loving Corrections, manifest in this fictional world, especially because seeing them dramatized is really, I think, unforgettable. But before we explore that, I think we need to do a little bit of world-building together and discuss what I would call the 3Ds: the situation, the disease, the setting, Detroit, and the main character, Dune, all of whom we encounter at the beginning of the first book Grievers. It's really impossible to separate these three elements, I think. But let's start with the disease. The disease that Dune's mother is patient zero of, and which only seems to be happening in Detroit. Talk to us about Syndrome H8, both what it looks like when you get it, what it looks like if you come across someone with it, who gets it, what we know or what we don't know, and even what you were thinking about as you began imagining it.

AMB: Beautiful. Yeah, maybe I will answer that a little in reverse, is what I was thinking about. I moved to Detroit in 2009, and I started writing this text in like 2011. Part of why was because being in Detroit was being in this city that was both a ghost town and felt like a place of tons of new birth. So driving around, I was with someone who loved to share the history of the city. We would drive around and they would point out things like, that used to be the Motown building, and actually, when they demolished it, there were Stevie Wonder lyric pages flying down the street. And that used to be this and that used to—like they would point stuff out like, this was a major place in our labor history, and this is a major place. And there was just a sense of, like, there was so much that was here, and a ton of it was empty lots. So it would look like this is a spacious city, but if you were with someone who knew the history, they were like, "This used to be a booming block, a community, like tons of people here, and now they're all gone." Once you knew that, it was like, "Oh, of course you can feel the presence of all that's not here." So Syndrome H8—when that came to me, it was like, what would it look like if the grief that we feel about being in places where everything is gone, or where all of our people are gone, what would it feel like if that was quantifiable as like a physical grief, a physical experience that other people would be like, "Oh, they're in that place. They've crossed over into this unimaginable grief that you can't necessarily return from." I was like, is calling it H8, which is hate, is that too on the nose? But I was like, "I want to make it as clear as I can that there's something about this disease that is targeted at people." Because I was sitting with that. I'm like, "The impact of living inside of a people who other people don't want to exist manifests in our physical bodies and makes it almost impossible for us to live into our full capacity of life, our full lifespan." I know so many people with so many different stories where they're like, "I know that the stress of living under racism and inside of patriarchy and inside of capitalism and all these other things—I know that—" I remember friend Alexis Pauline Gumbs when her dad died, she was like, "I know because he's Black, that that played a part in why he died so early." I grew up in those stories where my grandmother and great-grandmother died in hospitals where it felt like they didn't get the care they needed. So anyway, all of that was swirling around. I was like, "What if that was a disease? If we were able to say there's a disease that's targeting Black people." So what happens to Dune is she watches her mother get this. She's witnessing—they're in the kitchen together and all of a sudden her mother, who's mid-sentence, just stops talking. And she's just kind of glazed and staring straight ahead. And she's breathing, but that's it. There's no other sign of functionality. There's no will. There's no capacity to move. There's no capacity to respond. There's no sense that there's anybody inside able to bond. In that first book, it's a mystery what's happening for the person. We don't actually know what the experience is like from inside. In truth, throughout the book, you never fully understand what that is, but I give some strong hints of, you know, that felt like me just being like, I have some assessments of what happens in the spirit realm, but I'm not going to fully assert it. But I do know that they don't die. They transition. They move to a different consciousness and a different reality, a different place of spirit. That felt important for me because I was like, I'm surrounded by spirit. I think anyone in Detroit will know this feeling. I think there's other cities that carry this too. Like when I'm in New Orleans, I'm like, "This place is thick, much thicker than the amount of people standing around me right now. I can just feel the layers." Anyway, so the syndrome happens and it's targeting Black people. We don't know that right away, but pretty soon it becomes clear that that's who is coming down with this, and no one is recovering. It's like, once you get this, your systems all shut down. You stop receiving food. There's just nothing that is translating out. It's like a comatose state. That quickly overwhelms the entire medical structure of Detroit. So then it becomes, well, who can receive care? And does it make sense to receive care when no one is recovering? Then they end up quarantining the city. Later along in the journey, you'll learn that there's a manmade component to this syndrome. That felt important to me too, because I think most of the things our folks are sick with now are manmade. So yeah, there's some stuff around H8.

DN: Well, because there's so little known about what it is or how it's spread, much like with COVID at the beginning, and the debate between say a lab leak and a market spillover. There are various theories about H8 and N1 given that it affects only Black people, like you said, is that it's manmade and that it was actually created specifically to target Black people in one of the blackest cities in America. I initially presumed that this was you working through and being inspired by your own experience in pandemic lockdown, but that isn’t the case at all. Our first question for you is actually about this. The question comes from the writer, artist, facilitator, mother, and theologian Autumn Brown—the front-woman of the eponymously named soul-pop band Autumn. She’s also a writer of speculative fiction and creative nonfiction, and she co-hosts the amazing podcast “How to Survive the End of the World” with her sister Adrienne Maree Brown. [laughter] So here’s a question for you from Autumn.

Autumn Brown: Hey, sister, surprise.

AMB: [Laughs] What a good surprise.

Autumn Brown: It’s kind of weird that we’ve never talked about this, but here’s my question about the Grievers Trilogy. The first book of the trilogy is published in September 2021, yet you started writing that book—which is about a pandemic of grief—long before the COVID-19 pandemic actually began, and the other two books are written in the wake of the pandemic. Most readers of science fiction will recognize the narrative device of a pandemic as a really effective way of looking at one of the core questions science fiction asks, which is, “If we keep going down this path, then what?” It’s an incredible device for looking at how social relationships can be rapidly reshaped by rapidly unfolding conditions beyond our control, which is arguably what is actually true most of the time. But I digress. The thing I want to ask you is this: how did living through an actual pandemic shape the writing process for the series as a whole? The virus, this grief disease, is sort of its own character in the series. How did you come to understand its role in the story and how was that shaped by our actual lives? That's my question. I love you so much.

AMB: Love you too.

Autumn Brown: I hope you're having a good time recording. Okay, bye.

AMB: [Laughs] That's such a sweet surprise and a good question. Yeah, one thing to understand is I had written the book, I started writing in 2011. It first showed up as a short story. And, you know, when I went to VONA, when I went to Voices of Our Nation, I had Tananarive Due as my teacher for a week of scholarship. We brought the story there, we worked it there. She was like, "You want to understand the short story and then build on as much as you can." I worked on it for years. It kept being like a short story, a play, I kept changing form. Then when Black Dawn was like, "Do you have anything that could work to launch this series?" I sent them this manuscript and they basically came back—Zenobia came back—and she was like, "I think you have the first two books of a trilogy here." So both Grievers and Maroons were mostly written, I'd say like 75% of them were written before the pandemic, this COVID-19 pandemic. So I learned a lot when we went through actual COVID. One of the biggest lessons, because one of the things I was concerned about in the book, that always worries me when I'm in any sci-fi world is how much can I just focus on this world that I'm in and how much do I need to think about how the rest of the world would respond to what's happening here? How much do I need to attend to the world beyond the borders in which I want to work right now?" I was like, "I want to be in Detroit, with the understanding that Grace Lee Boggs had always dropped in, which is like, "Detroit shows what the rest of the country has to look forward to. Detroit shows what the rest of the world has to look forward to." Like there's something particular about what happens here with capitalism and race and the ecology of the place that is a foreshadowing. So I was like, "If I can just focus on Detroit, I will learn something about the rest of this country's possibility and potential." So going through actual COVID-19 was really helpful because initially when it was contained, when it was like there's something going on in China, there was a real sense of like, "Oh, that's far away from me," and "It's scary, I'm sad that that's happening, but it's far away from my life." The immediate crisis of my life continued to take precedent. Then when they were like, "Oh, now it's here. Now it's closer," I happened to be in Italy when it reached Italy, and I was on sabbatical. So I was very much like not watching the news, not on social media, like not tuning in. I landed in Italy two weeks before everything, the whole world shut down, like right at the beginning of March of that year. So all of a sudden, because I was there, it mattered. I started having to pay attention and family members were like, "Do you understand what's going on?" I was like, "Oh." So suddenly it became relevant to me. But so that idea of like, "When did it become relevant to me? When did it become something that was impacting my life?" helps me feel permission to really dive in to the Detroit of it all. Because I was like, because they quarantined relatively quickly and whatever this is is starting here, it's happening here. It was okay, you know, I was like, "Oh yeah." Especially the pace of crisis between 2011 to 2020 and 2021 picked up so rapidly that like the amount of people that would have paid attention, I think in 2011 even to something happening in one place, was already different. Less people can pay attention to anything that's happening anywhere now, like we live in this world. So I was like, "Okay, I can just dive in in Detroit." I know that like people will be like, "Something weird is happening in Detroit, but we don't really know what's going on there." There are so many other crises going on. We're not going to hyper-focus. So I was like, "Okay, I can just kind of like let my folks go through this experience." I think the other small strange thing was like, in my first book in Grievers, I hadn't written people having like masks or doing any of that. I was like, "Oh, right." I didn't go overboard with that, but I was like, that's one of the things that quickly I learned. I was like, "Oh yeah, when there's a pandemic, people suddenly like PPEs, like we got to cover our face and cover our hands and do all this stuff." The way that the syndrome moves is like, people don't have a sense of how it spreads. People are like, "Maybe it's in the water, maybe it's in the air," like we're not quite sure, at least initially. I remember that part of COVID-19 and being like, "Yeah," like the uncertainty, like being inside the population where everything is happening around you and people are just dying all around you. I wanted to capture that feeling of like the person you run into on the corner or at the store or in line for donated goods or something, they might be the ones who are giving you the information or more trustworthy information than what you're getting from the news. The news is doing the sort of broader strokes thing, either catastrophizing it or trying to be very theoretical with the doctors or whatever. All of that felt like I was like, "Oh, going through the experience of COVID helped me to, I think, ground the pandemic that was happening in the book in more sense of like, yeah, here's what we really do." But I also wanted to catch that feeling of waiting. So that's before COVID-19 ever came along from my doula work—birth doula, death doula, sickness doula, all that stuff. So much of me is waiting, sitting, and feeling, and not being able to do anything. So Grievers, I really gave Dune permission to just be in such overwhelming grief but also something in her still wanting to stay alive and my experience of grief, that's exactly the heart of it, is being like, "It's just too much to feel the loss." But something in me still wants to stay just enough alive that I'm going to nourish myself or give myself some water. I let her go further than I've ever gone. When I'm grieving, I still usually try to buck up and participate in things. I was like, "Well, what would the level of crisis need to be where I didn't even feel I needed to do that anymore?" COVID-2019 gave me that lived experience too where I was like, "I'm not going to buckle up. I'm going to sit in my house and cry." Then thinking about how long it takes for people to want to return to normal, I think that shaped the second two books. Maroons and Ancestors both feel like, I’ve been astounded by how quickly this world has wanted to blow past the safety protocols that we knew would help us to get back to normal. That's both true within the communities that have gone through hurt and through pain in a larger society. So I was able to work with that to be like, "Yeah, even if you're living inside of a total apocalypse, there's some part that's like, 'Okay, how do we create some normalcy and some rhythms of community here? If we're by ourselves, if we're in small groups, if we're in a larger societal experiment, how do we give ourselves something that feels normal and how important it is to our desire to continue?'" So yeah, those are some of the ways that it interplayed with the writing process.

DN: Well, you could definitely read this trilogy as the deepest of love letters to Detroit. This book couldn't be more lovingly place-based. I've never been there, but I feel like I have been there now. I was even rooting for the Pistons in the playoffs this year because of your books.

AMB: Yes. [laughs] Thank you.

DN: I feel like you've already spoken into why Detroit and what Detroit provides as a setting, what lens it gives us into the past, present, and future of our country. But I wanted to ask you about how you portray the world in Detroit. The first book in the trilogy is the most fraught book. It has all the fear and isolation that an unknown plague brings with it. It has a lot of other things too, but compared to the other books, things are the most dystopian at the beginning. Yet, unlike Octavia Butler's Parable of the Sower, where resource scarcity and poverty and the breakdown of government services leads to immense violence, the breakdown of societal norms, even the rise of modern-day slavery and human trafficking, and mentions in passing of the possibility of cannibalism, your book, even at its most dystopic moments, has none of this. The books aren't about this. They are about survival, about grief, and about death in that first book, but mainly not in competition with anyone else. I wondered if you could spend a moment talking about this choice in the series, which I think deeply affects the tenor and the atmosphere of the trilogy as a whole.

AMB: I kind of went back and forth on this one. I feel like I've read so many texts where the worst of us comes out and we turn on each other and everyone's stealing from each other, killing each other, all these other things are happening. But then I've lived through multiple large-scale crises in my life. What I've noticed is how quickly people turn towards care and towards trying to help each other and also towards some anarchy. That there's a way that people are like, "Okay, whoever we thought was going to get us through this or get us out of this doesn't seem to be present right now." So we've gotta figure this out and how quickly people become capable of providing something to their communities. So I wanted to lean into that. That might be the most utopian aspect of these books. Like I really tried not to make a utopia. I got in some trouble with my ancestors by the book, by the end of Maroons, because they were like, "Girl, that's a utopia. You need to get it together." [laughter] But, you know, I never think of a maroon space as utopia, because I'm like, what it actually takes to survive in a place that is not set up the way you were societally trained to survive can feel like such labor that it's like, "Oh, this isn’t the utopia I was thinking of." Most of us, I think when we imagine utopia, there's still this—even if we're not aware of it—there's still this sense of "someone is taking care of us." I'm like, "Well, whoever's taking care of you is not in the utopia generally." So anyway, that doesn't mean some of these things aren't happening. There's a scene where Dune goes into a grocery store that she thinks is abandoned and there's someone in there and they're armed and there's this sense of danger and this sense of "Oh, if I wasn't me or if I wasn't able to come up with a coherent story for why I was here, this might not go well," that she's on guard. But then I also wanted to represent like even the people protecting that store, like anyone else, they're just trying to also survive. I was like, "What if everyone in this story is written as someone who's trying to survive with some benevolence and some compassion rather than writing about it as like, these people are trying to survive and they'll kill everybody, you know?" It felt really helpful to write it that way and to imagine it that way and to imagine into what I felt. Also, the COVID-19 experience reiterated this into my heart, it was like, look, folks are not running in the streets and stealing from anybody. Everybody's just trying to stay safe and trying to get their needs met. And if any running is happening, it's people with resources running to hoard what they can from the stores, but everyone's just like, "How are we going to do this? Do I have the privilege to make adaptations for this thing or am I an 'essential worker' where that means I don't have necessarily the same agency other people do to stay safe?" I was much more interested in the internal work of letting a society break down inside you, and then having to figure out what makes life worth living and who makes life worth living on the other side of that. I'll also say there's something here around when you feel like you're of a community versus looking from the outside. I keep thinking about this watching Gaza or stories about the Sudan, the Congo, and places where I'm like, from the outside, we just see this death and destruction and the horrors of it all. But from within, there are just people who are like, "I'm trying to keep my kids engaged through this struggle, and I'm trying to find some bread today." Everyone's a human being, so everyone's trying to do the same things we would all try to do in those moments, which is, "I've got to take care of basic needs and I've got to take care of the people around me." And that's what I experienced living in Detroit, was a lot of people who are rooted in care and trying to figure out how to offer care to each other. So yeah, I gave myself permission to focus on the emotions of the characters that I was in and not giving them a multitude of existential crises. Also, I'm like, there's already enough. Having a pandemic is enough. Living on an Earth that is in crisis is already enough.

DN: I love that element of the book. I also love this notion of you, what you just said about breaking down society inside of us.

AMB: Inside of us. That’s the piece. So Dune is the main character and she is the child of two activists, organizers in Detroit, but she grows up as kids do, a little in opposition or a little like, I'm going to do my own thing." So she grew up steeped in all this culture of organizing, but then she was like, "I don't quite know what my calling is yet. I know my mom's not able to really create stability. So I'm trying to figure this stuff out," but so I'm like, she's double socialized already in both the American experiment and the revolutionary reaction to that. So then when all the things get pulled out from under her, she's got to figure out, "Which parts of this are going to break down within me. And then who do I want to be?" I love that part of the answer to that is like not alone. You know, she really tries on aloneness to an extreme degree, but then it's like, "Okay." Then when stuff starts breaking down inside of you, I also wanted to rebuild it very slowly. You know, I think a lot of times when people talk about, "You need to find your community," there's this idea that you're going to like drop into something that's already like a highly functional, multitudinous group of people who all have like working agreements and everything's going well, but that's not how I have ever built community. It's always been one by one and like letting myself be drawn into the companionship of one person at a time or one creature at a time. So that's the other part that felt important. It's like, stuff is breaking down. Now you have all these people who are like, "Okay, we're all on the other side of this breakdown and it's breaking down inside of us in different ways." So then when she finally is drawn to someone and it's like, "I do want to go find that voice. I want to find this person," it's someone else who society is breaking down inside of them as well and together they're both like, "Well maybe the ghosts matter, like maybe the people who are dying matter, maybe this place matters." You know, we're not sure yet, but we have some hypotheses that it matters to be here and be alive and be paying attention and like really that's their only common ground at the beginning.

DN: Well, I think it's crucial that Dune is, unlike her parents, not predisposed towards collectivity in organizing but an introvert.

AMB: She's an introvert. She has to be by herself. [laughter]

DN: She's confronted with a rupture of intergenerational knowledge because of H8, and we watch Dune learn to cook through books instead of from another person. We watch as she puzzles out, gleaning from various community gardens. As she starts to become an archivist of sorts about the disease by using her father's model of Detroit in their basement to record where she discovers people who have died, recording the seemingly nonsensical words each person keeps repeating when they're still alive but immobilized. She doesn't know if a pattern will emerge from her data. She doesn't know if she will be the person to discover the pattern if there is a pattern, but the act of archiving feels to me like something at a minimum she can leave for the future. But all along the way what stands out to me, in Grievers, is how you dramatize dailiness, the unglamorous quotidian acts of caretaking. She lives with her largely nonverbal, elderly grandmother who depends upon her, and that dependence involves repetition, the wiping of butts, bathing another person's body, changing a diaper, without much gratitude in return, and along with her work learning to glean, to can preserves, and to cook. It is all work that's often feminized, that's considered feminine work, work that is usually deemed unworthy of being dramatized, but here you dramatize it. It reminds me of the animating questions in Le Guin's Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. How it was the male hunters who had their hunts glorified when they came back with a kill and then told their stories about the hunt. Even when the meat was largely incidental to the survival of the people, which was mainly sustained by the work of women, not the hunting but the gathering. An activity that was not seen worthy of story. But similar to how your story of quarantine Detroit doesn't center vigilantism and conflict, it also doesn't center heroism. It feels like you're showing how one could not only create a future archive around an unknown disease, but also begin to archive knowledge of how to live and survive through the act of doing it. I'd love to hear more about this aspect of Dune's life and if there is indeed a philosophy underpinning what you're centering here, whether wiping a grandmother's bottom and wiping it again or gleaning in the fields.

AMB: Yeah, thank you. I love that you picked up on this piece, the larger piece, because back when I was in that "VONA" moment, that like 2013–14 era, Octavia's Brood was bubbling up. Walidah Imarisha and I were starting to work on this collection of short stories from science fiction movements. One of the things we talked about was to write fiction, there has to be some core conflict, and that's how all fiction exists. I found myself really wondering about that. I'm like, "What would it feel like to have a book where the motivating energy wasn't coming from conflict, but was coming from something else?" Is it possible that that energy could be the will to live or the will to care or to become more tangible in what you're doing in your daily life? Dune is someone who's been a wage worker. You know, she's not someone who's like, "I've got this like massive purpose that I'm serving." She's very young and she's still figuring that stuff out, you know? So I was like, "Yeah, could I at least do this book?" I think in the next books, I allow a little bit more of the conflict and there's some more dynamism going on. But in this one, I was like, "Well, really, how do you become a whole human being?" In my life experience, it's been that doula work, those doula moments, which inform a lot of Emergent Strategy as well, which is like, "Can I slow myself down enough to attend to the adaptation that's needed here? Am I willing to do whatever, again, that work is that has been devalued?" In this state situation, it's like, there's no one else I can hire. There's not someone I can hire to come do this for me. I think there's always the sense of community just beyond her reach, but she's unable to do that in her grief. She's not able to reach beyond the boundaries of the house initially. So then it's like, how much can happen inside of this world? I've had so many caretakers. I've really got to be around and with and in the work of caretaking for so much of my adult life. I think those are the best people I know. The people who, yeah, stay, and they're like, "I will do the act every day and the listening to the repetition." This is one of the aspects of H8 survivors is a lot of them will have these words that they get stuck on repeating and they just keep saying over and over and over again. In a way that's like some of it's sensical, some of it's nonsensical, but if you've ever been around, especially elder people who are on their path out, a lot of times they kind of whittle down to these repeated interactions or repeated words or repeated memories, and it's like these are the core gems of my life. This is the thing that, as everything else is passing away, I keep coming back to. When I was sitting with Grace as she was in hospice, she kept remembering her brother who had long been gone, but she kept remembering him as if he was there in the room with us and having conversations with him, conversations with her dead mother. So, yeah, I kept thinking about what, what are the essence, I'm like, "If this grief pulls us down to just the little crystallization that's left after everything, what are those stones?" You know? So there's something about being, "Can I just hold the stones and keep holding them and keep holding them and sitting with them and seeing if some pattern emerges from being with them?" Can I be in the care and see if something emerges? For Dune it absolutely does. Like she's not healed in some big epic magical way initially. Like magic is definitely flowing through her and we start to see that. But what's actually healing her is the repeated motion of care and being like, "I'm the person who's going to stay in care and it doesn't make me better or worse than anyone else, but it makes me a contribution." I love the moment when she has to start figuring out like that she has to care for herself as well. Grievers really closes with that moment of like, "Oh, like I'm alive and I'm going to care for myself and I'm going to indulge and be good to myself and we'll see what happens from that."

DN: You mentioned recently in your newsletter some shows that you've really loved and two of them were The Pit and Dying for Sex.

AMB: Yes.

DN: I found The Pit incredibly grounding and therapeutic which seems weird because everything is going wrong all the time.

AMB: All the time. [laughs]

DN: Yeah, misery and pain is the climate. But the way Dr. Robby goes through this never-ending, unmanageable and under-resourced situation and tries to remain human and to teach and to heal and to listen is just amazing. I think of that and I also think of Dying for Sex’s beautiful, unflinching ability to be with death and dying in all of its textures and nuances, including the beauty and the humor of it, but also the holiness of it, I think. I can see why you love these shows in the way that you portrayed Dune, figuring it all out while losing everything she knows.

AMB: Yeah, absolutely. Like I really love watching any, I mean, the TV shows that will get me every time are the ones that are not positing that things are good or things are awful, but things are existing. Like what it means to be human is to be with the full realm. Like you're going to be grieving. You're going to be overcome by what humans are doing to each other. You're going to be overcome by how powerless we are in the face of trying to protect our loved ones and some really sweet thing is going to happen or some fucking hilarious thing is going to happen or it's all going to be there at the same time. Both of those shows I was like, I'm hooked and this is how I also want to be creating. I want to create worlds and people where folks are like, "Oh yeah, like I can feel the humanity of that." Like Dune is overwhelmed with grief and then she's masturbating and then she's going to figure out how to cook a cake or what, it's like she's just a person in a life. I think that grief, again, there's this way that we'd be like, "Oh, when someone loses someone," I think sometimes we can pull away or be like, "Oh yeah, they've just got to be in their grief." It's a busy thing, to-do list full of, "No, I'm just sitting here crying." I'm sitting here crying and maybe it would be nice if someone came and sat on the porch with me for that and didn't ask me to be or do anything other than that. Then when we're sitting on that porch, we're probably going to laugh and we might have a smoke. Like the humanity is always there and I love thinking about some of the biggest laughter I've ever experienced has been at a funeral, in that you're building your plate of mac and cheese afterwards or whatever and it's just like, "Oh yeah, remember the person that just died was also kind of like an asshole, but like we love them and remember when they did this thing to us," it all seems so beautiful in retrospect to look at a life and be like, "Oh yeah, like this person did all these things and I just got to love that person," right? They don't go out with like some saintly halo over them. No one really does. Everybody goes out like a person. So it was really beautiful to get to write this and have these people where like Dune, Dune's mom is a hero to everyone else in Detroit, they all like respect and love her so much, but like most organizers’ kids, they're like, "Oh my gosh, my mom's never got her shit together. She's not around," or whatever it is. I was just like, "Yeah, let's just have all that be here." Her mom is an outstanding person who's also not a saint and Dune is not a saint and that she doesn't have to become one for the story to work, but she does have to be willing to be a little magical because that's also part of being human. It's like contributing to the magic of it all. I wanted all that in there.

DN: Yeah. Well, one aspect of the books I really like are the occasional songs. Later in the trilogy, the Ancestor journals, the way we move into a different relationship to language when we encounter these other forms, it's a completely different reading experience. I think of how Le Guin’s Always Coming Home has this too, and also has many songs, moving into different modes of language. In Grievers, Dune sings a song at one point that was particularly memorable, and two of the stanzas go: "What is the freedom road when all the warriors have gone home, when all the healers sleep alone? Who else will bear this load? How does the galaxy hold all this pain and not knowing? Hold all this pain and keep glowing. Who am I meant to be?" In the aura of these lyrics, we have a question for you from the writer Daniel Alarcón. He's the host of the Spanish-language podcast Radio Ambulante. His story collection, The King Is Always Above the People, was long-listed for the National Book Award. In 2021, he was the recipient of the MacArthur Genius Grant. So here's a question for you from Daniel.

Daniel Alarcón: Hey, hi Adrienne. This is your old friend, Daniel Alarcón. I'm so excited and honored to be a kind of remote participant in this interview that you're doing. I have known you since 1997, so quite a long time. I still remember the first time I saw you perform, like sing, it was pretty revelatory and I knew you sang and I knew that music was a really important part of your identity and your craft as an artist, but I had never heard you sing before besides like, you know, kind of like the kind of singing everyone does in the radio or at a bar when a song comes on. So this is the first time I heard you sing at a performance in New York. It was around this time of year, this is May right now, I'm sitting in the park and I heard you sing and it was beautiful. It was remarkable for me to sort of discover and appreciate my dear friend in a different light with a different set of talents that were kind of almost unimaginable to me, the way you would perform a melody and hit these high notes. It was just very moving. I was just so in awe. So my question for you is about singing and about performance. I'm just wondering how it intersects with your work as a writer. Because I do feel like your writing has a certain lyricism but I'm just interested in the relationship between those two art forms, writing and singing and music and the written word. So I hope you can expand on that, and I can't wait to hear your answer, and I love you, and I'm super proud to be your friend. Take care.

AMB: Oh my God. [laughter] It's so sweet. I love this, like, this is your life thing. So, yeah, Daniel and I co-edited a magazine together at Columbia University called Roots and Culture and he was a year ahead of me I think or two but I just was always like "Oh he's the best writer I've ever met in my life and I'm glad to know him" and yeah so it's really beautiful to hear his voice and yeah I love this question. So I think the truth about song for me is probably that that's the root system, like actually the way things move through my body is melodies and lyrics and song. When I'm singing and what I love about singing, you don't need any words if you get the sound true. If you can really let a true thing come all the way up through you and fill it up and through the lungs and get it out through your, and if it can still be true when it comes out, it doesn't matter the perfection of it, it just matters that it is so true. You know when you hear something or you know when you sing something, you're just like, "This is it." I'm not contorting. I'm not shrinking. I'm just letting the full thing be here. It may sound very quiet. It may sound very loud, but it's just like, is it the real thing? And in some ways it's much harder, like doing this project, writing across three books and being like, "Okay, there's a character and I have to build a world around this character and I have to have dialogue and there has to be all these other things," there's sometimes a part of me that's like, "Can I just sing Dune's song and everyone will just know what they need to know about it and we can keep it moving?" But then sometimes a song, I often will hear a song and be like, "God, I wish I knew every single detail about that lyric. Where did it come from? Who said it? Who felt it?" Like it comes down to essence, like poetry can sometimes come down to essence. So then it's like, can I give myself permission? I loved with these books that I was like, "Let me just dance with going back and forth between them." I liked that I wanted to make Dune a singer who wasn't like a performer singer but she was just someone who was like "Songs spill through me and I can use them to help people or comfort people." And the songs that came through here I still, my plan is still to record these songs and release them as their own little album project because they're all very distinct. They have, you know, this one, "What is the freedom role when ♪ The warriors have gone home ♪ ♪ When all the healers sleep alone ♪ ♪ Who else will bear this load ♪" Like it's just like clear in my head, like this is how Dune sits and she just sings for her grandma or whatever. When people are dying, a lot of times they'll ask to be sung to, or they'll have favorite songs they want to hear over and over again too. It's this universal language. That's the other part for me about songs and music in general. Like I love being someone who, I'll hear a song from Molly or I'll hear a song from China or hear something and I'll be like, "I don't know the words but I know what this means. I know what this feels like. I understand it." Yeah, I feel like songs can take us beyond translation. Then coming back into the realm of the stories, it's like, "Okay. Now I've got to say something that will need translation," and both things are really useful for the brain and for the human experience.

DN: Just hearing that little snippet, you feel—or I feel in my body—just how much more is coming from the song, where I don't even want to ask you more questions. I want to lay down and have you keep singing. [laughter]

AMB: You want to lay down, I'll sing to you. [laughter]

DN: That's what I want. I mean, that's what it creates, that desire. It feels like it's transmitting something that no matter how much conversation we have isn't being transmitted.

AMB: It's a different thing, right? It's different. I think there's a spirit in the song. If you sing it right, if you get out of the way of it, that's also taken some learning because when Daniel saw me sing, I was taking voice lessons. I was studying song and I was really learning like how vast my voice could be. I had a voice teacher that I would meet up in the rooftop level at Barnard. There was just like sort of greenhouse room where I could see all the way down the city. She'd be like, "Sing it down to the Empire State Building, sing it all the way down," and I'd be like, "Huh?" You know, like just really like, "How... how... whoa, whoa... how big can you go?" But I trained. I really trained myself to sing and then I kind of had to kick all that away because I had trained myself to sound very pretty, but it wasn't necessarily very truthful. Like I was much more focused on how pretty the notes would be. What I love about then the songwriting that has emerged later in my life has been like an almost channeling, just really giving myself over and being like "Spirit, come use my body and my voice right now." I often find out how I feel about things because I just let myself sing and then something comes out. There's another song in this book that's "♪ ♪ I think too much about how I will die.♪ ♪" That song, it came before I really understood that it went with this book and it just was looping. I was like, "This is my own suicidal ideation literally looping through me," the way I process the grief of being alive and recognizing how precious and incredible aliveness in the world is, and then recognizing that there are people who don't feel that preciousness and that I will spend my whole life trying to be a voice of the preciousness up against this force of, you know, that numbness or that void, that emptiness. It's like, I watched The NeverEnding Story at a formative moment in my life. Like I was like, "The Nothingness!" [laughter] It's like, there are those of us who are like, "I love being alive so much that I can barely speak and I can barely get my breath together," and it's just so beautiful. Song is the place where that can just flow through me. But also the grief of being like, yeah, I'm on this earth and there's nothing I can do in my lifetime that will convince all the other people on this earth by the time I die to give themselves over to this beautiful life experience. Like that's grief feeling. You know, I'm like, "Oh, I can't bring you all to the heaven that we live on." Like we live here, it's beautiful, but part of the experiment of The Grievers Trilogy was like, "Can I make one pocket sacred and just show what that would look like and how it would sound?" So they're singing all the way to the very end of that.

DN: Well, there's this scene that I think of a lot from the trilogy where the National Guard are wanting to evacuate people. There's already been a mass exodus and simultaneously a quarantine. An organizer activist, Eloise, who's pissed about being told to go, says she won't leave until everyone can leave. But she also admits that she would be equally pissed if she were told she had to stay. Somehow, this feels like a key to me. It's a scene that has me imagining into Eloise's history in Detroit, both the way Detroit has already been abandoned long before the plague but also how Detroit, as you've mentioned, has already been doing intense solidarity work before the plague too, that perhaps the plague is amplifying something about Detroit in both directions. I want to talk about Detroit, both by circumstance and ultimately by intention,n becoming a Maroon community and becoming this pocket where this song is sung, and what challenges it has because of this. But before we do that, first in the broadest strokes, I'd love to spend a moment about another shift that happens in mode from Grievers to the second book, Maroons. In the first book, as we've talked about, Dune is largely alone, and she's even mostly in her own head when she is with others. It's a situation that in some ways suits her, but perhaps to a fault. Maroons is a dramatic shift into the relational, and I wanted to talk about the various ways it becomes more deeply relational. The way Dune moves the trilogy into a much more deeply connected place is first by hearing a pirate radio broadcast and trying to find where it is coming from. The show is called Everything Awesome Circus and the host Dawud, goes into these wild verbal riffs that—like the songs and like the ancestor journals in the book—they have their own syntax and they have their own style. So many of these broadcasts are really great. I think of one where he says, "There are four things that matter. One, looking into someone's eyes. Two, sleeping deeply enough to dream. Three, saying exactly what you mean. Four, being creative." When he says in his slant rhyme style, "All I have really tried to do since I got here was plant seeds of joy and water them with laughter in the shadow of disaster in the fucking cold," it reminded me of your recent appearance on Tananarive Due’s podcast, Lifewriting, where you talked about how you love podcasts because of the way they feel related to radio, of hearing someone come into the room in this way. I’d add that podcasts, like pirate radio, but unlike broadcast radio, have no set form. An episode could be thirty seconds long, or, like this podcast, four-hundred-thousand hours long. [laughter] But here we are, finding intimacy at a distance in this broadcast, storytelling, oral form. I wondered if you wanted to say anything about Everything Awesome Circus and the experience of writing it, or even perhaps read a paragraph or two of a broadcast riff you want to read for us as part of that.

AMB: I think that I've mentioned before that all the characters in this trilogy are based on people who actually passed away during my time in Detroit so they're people that I knew and they're people that I lost. They're sketched after these people. So they're not like, "This is the person," but it's like, oh, I want to honor. "Dune really looks like this organizer named Shetty, who was one of the first people to ever pick me up from the airport with Jenny Lee." So Dawud is based on this poet named David Blair. David Blair, one of the best poets that we've ever had who passed away from a heat stroke in Detroit. But his poems were like mind-blowing to me and he was this bombastic, beautiful gay Black man who was just brilliant and exacting. So when I was thinking about The Everything Awesome Circus, I was like, "I want something where someone is just leaning into being unhinged, is poetic, is like a little scared and a little alone," but also just like, "We might as well fucking enjoy this." Like, we're at the end of it all. So there's something about that. That I was like, there's someone who was like, "I could be serious and I could do all these kinds of things, but like, I'm also, I don't know, I'm just figuring it out." So I had the best time ever writing those sections, like really just letting myself be like, well—and I'm someone who, like, I came up at an edge with spoken word where some people were like really into spoken word and other people are like, "Hell no, don't do spoken word, whatever." [laughter] And I was like, I think if I'd been born maybe a few years earlier I might have just become like a spoken word poet and just gone that route. But this felt like it allowed me to play into that. So maybe I'll just read the first way we hear Dawud and I'll see if I can get the—I used to have it very clear in my head—his rhythm, his rhythm.

[Adrienne Maree Brown reads from Ancestors: A Grievers Novel]

DN: So good. [laughter]

AMB: He's so fun. I'm like, "He's just such a trip." You know, Detroit has all these characters who are so unique, like just right now, you go to Detroit. Every time I'm in Detroit, I'm like, "There's someone I'll get in a conversation with," and I'm like, "This conversation is unhinged from the rhythms of a normal social interaction. It's suddenly intimate and it's wide-ranging and it's poetic and it's all the things." It'll just be with like the Black man standing at the bus station or the person who's like driving your car or whatever. Blair was like that, where like you'd ask him a question and the answer you would get would take you in a totally different direction, but it was a worthwhile divergence. I also, as a podcaster and a podcast listener and a radio, I'm like, I love the form of someone sitting alone and letting themselves fly into whatever realms they need to explore. Then putting that out there with the idea of, you know, it's that message in a bottle move. That's like, "I'm going to put this out there and we'll see what happens." Dawud is like that, where he's like, "I might be the only person actually left here. I came with the National Guard and they've kind of abandoned the project, but I haven't found my family yet and I'm still here and I don't know if anyone else is out there." And Dune is like listening to him like, "I didn't know anyone else was out there, but now that I know you're out there, I need to meet you." And it was also important to me that like he not talk like that in real life. So it's like he has his show persona, Dawud be in the place to be, but then when she meets him, he's like this kind of curmudgeonly, gruff person. That also feels very Detroit. It's like, you'll have these people who are like doing whatever dynamic magic. Then when you meet them, they're just like—and I'm like, great. These are my people. I love a good curmudgeon. Poetic curmudgeon.

DN: Me too. Well, extending your notion of something unhinged from social norms, and staying with the relational shift in Maroons. Maroons is extremely sexual. Lots of sex portrayed in it. To me it is the relationship between Dune and Dawud—not just sexually, but in every way, including the sexual—that feels like a decoder key to something you're exploring around creating relations as part of dreaming and otherwise into being, especially when the dreaming by definition isn't just your dream. So Dune and Dawud are both queer, but Dune dates other women and Dawud other men, but here they're creating a relationship where it isn't the normative society looking from the outside in, calling their dating queer. It is queer to both of them from the inside, queer and strange in a way that challenges how they see themselves, that requires them to in some ways become unfamiliar to themselves. It almost feels like it's queer squared.

AMB: Yes. [laughter]

DN: It requires a lot of imagination, practice, experimentation, communication. And I want to read a lot into this relationship. Perhaps I'm reading too much into this relationship, but it is very clear that they aren't together in the end because of limited options, even if limited options may have forced them into a consideration of this in the first place. I wonder if there is a subtext to this central relationship. We talked last time about fractals, about things mirroring and echoing each other at all scales that if you want democracy in the world, you've often said, "Have you looked at how you conduct your own household? Have you started with the ways you are every day in the world?" I wonder if you're suggesting Dune and Dawud's relationship in a way as a small-level fractal from which to move from to a larger scale love across difference.

AMB: Yeah, I absolutely am. You know, to me, there's so much that has happened with identity that has made it almost impossible for us to love each other. I think the way we're meant to love each other because some identities have chosen to focus on domination and other identities have had to then focus on surviving the domination. So then within ourselves, we can get very like hierarchical, even if we don't mean to. I remember when I first realized I was queer, it wasn't like, I like girls and now I only like girls. It was actually like an unhooking from rigidity. It was like, "Oh, I can like anyone. I can really feel attracted to anyone. The things that people tell me are supposed to matter here are not the things that matter to me." I would find myself having a conversation with someone who there was a huge age difference or there was a cultural gap that, you know, like I remember having a talk with a priest one time and being like, "This priest is so attractive. There's so much chemistry that's happening here. I don't want to act on that, but I just, I'm like, that's just real. There's just this really this feeling here and society says there wouldn't be." So I also have read so many post-apocalyptic things where people are just kind of thrown together and they end up just like casually having sex with someone or hooking up or whatever and just being like, "I don't know, you're the only person here, I guess we have to fucking survive." There was something about these people who are like, their primary love for both of them is Detroit. The primary relationship that both of them have chosen to be in is to be in Detroit, to stay there and to stay surviving there, even at the risk of madness, at the risk of not surviving, at the risk of losing agency or losing—if Dune, particularly for the first part of it, she's like, "If I get caught, they're going to just send me away from home and I'll have nothing at all left," you know? So they're both in this primary relationship to Detroit, which I think automatically decenters what would normally be their way of relating to each other. Then I liked the element of surprise for both of them, which I have experienced before in my life where I'm like, "I didn't expect to feel attracted or drawn to you, but I think I love you." Maybe that will be physically manifested and maybe it'll be something else. But like, I love those moments when it's like love is starting to emerge here and it's emerging where I was told I wouldn't. That to me always feels like the queerest thing we can do is to see possibility where we were told there is none and to see like, "Oh my, I already am something I was told can't exist." You know, like to be queer for most of us, at least in this time, is to be like, "I was never given this as an option. I was told it was bad. I was told I would be punished." Yet I just already am that. So I have to figure out how I want to live with that. I think for both of them, they're able to slip outside—again, this is the breaking down the society inside ourselves—it's like they're both able to without a lot of fanfare, that's the other thing I like about them is that they're not like, "Oh my God, this is," you know, they're just both like, "You're kind of giving hot right now." [laughter] You know, it's like, "I don't know, I'm just really like, I want to spend my time with you." I wanted that. I think this is one of the lessons that Octavia offered us is in her stories, people fall in love, even in the apocalyptic condition. There's something compelling that makes them want to move forward. Like there's something on the other side of the collapse and it's love. Like loving the earth and loving each other. That's what's on the other side of letting go of these systems that tell us they're taking care of us but they don't actually allow us to truly love each other the way we want to. To live in the US right now is like, "I love you and I won't be able to protect you from the state. I won't be able to protect you from the police. I won't be able to protect you from poverty. I won't be able to make sure you get the healthcare you need." You know, loving is like such battle. I wanted to show that if you remove a lot of those structures, then love can just be love. It can just be like, "I've got something I want to offer you. Do you want to receive it? Do you want to give back anything? Do we want to build something together?" Each decision that they make feels very like organic. Like there's no one pressing the other person. No one is like, "I'm the top and you're the bottom of this dynamic," which also felt like trying to reimagine relationships between men and women where you have removed those assumed dominant-subversive relationships, remove that part of it also felt exciting to me. I really wanted to explore just for myself, like, could I write sex scenes between them that would feel sexy to lesbians, sexy to gay men, and sexy to hetero people? Like how sexy could it get? So far the feedback has been really good on that. Like Alexis De Veaux reached out to me. She was like, "Yeah, I would get with Dawud," you know? [laughter] She's like the oldest, like the lesbian I know. So I was like, "Okay, cool. I think we're in." [laughter] I wanted him to be someone that was like, "This is a man that I could imagine sleeping with," but the dynamic between them, like neither of them has to give up who they are or the sex they like or the love they feel. I hope that you can feel like the sex could come and go, but the love relationship between them is core. It's like in relationship to Detroit. You've read Octavia's work. So she has the ooloi, that alien species that comes and it becomes like a third between the humans. There's a way for me that Detroit was like that a little bit with them, like at least in my mind, you know, it's like they both love the city and they're not going to leave the city. So that becomes the third part of their tripod. I find that when people love each other and they're place-based or they're like, "We both love the same places," or "We both love the same kind of places even," it creates this other third leg of solidarity in their relationship. So I wanted to show all of those different things, but I love their togetherness. It makes me really happy.

DN: Well, it was hard to know where to place this next question from another, because it could be anywhere in the interview, but also because where it is placed might change how you answer this question. Because one way I view the trilogy's movement, and I have no idea if you'd agree, which is, I think, a fractal relationship between the three books, is that Grievers involves more isolation and individuation, Maroons, more relation and chosen families, and Ancestors, more questions of larger collectives and solidarities, both horizontally in the contemporary moment, but also vertically across time and perhaps space-time. So I decided to place this question sort of in the middle of the arc of our conversation, instead of decidedly in one of these modes. This question is from the poet, the Arab American Book Award-winning novelist and psychologist Hala Alyan.

AMB: Ahh!

DN: Alyan's latest book is a memoir. It released this month called I'll Tell You When I'm Home. Past Between the Covers guest Kaveh Akbar says of it, "I'll Tell You When I'm Home feels as rich and supersaturated as contemporary consciousness itself. I can't stop talking about it." Current Between the Covers guest Adrienne Maree Brown says she wants her readers in the wound with her inside the stories that don't get told enough, inside the body-mind of a displaced woman struggling to create something bigger than herself. Brilliant. So here's a question for you from Hala.

AMB: I'm going to cry. Okay.

Hala Alyan: Hi, my beloved. It's Hala. First of all, congratulations, Alfa Mabruk. My question, unsurprisingly, is around care. I think you've done such tremendous beautiful work for so many of us thinking about and inviting us to think about care as such an essential, central part of capacity building, and endurance building. I sort of have two questions for you. The first is, how did you think about care while you were working on this specific project in this specific time, in the time that it was being written? So for this book, what did this particular story call for in terms of care, in terms of what was your system kind of craving during this time and how did you find it and then I'm curious about whether the writing itself felt like a form of care. You know there are some projects that I don't think "drain" is the right word, but there are some projects that exact a toll but their telling is necessary and their writing is necessary. And then there's some projects that just feel—at least for me—that have felt really kind of regenerative and sort of delicious and like that is its own form of care and that's its own form of reprieve. So I'm curious if you can speak a little bit about that. Love you.

AMB: I love Hala. [laughs] This is so good. Hala is such an incredible writer and an incredible human.

DN: She is.

AMB: She and I have been building like a deep friendship over this past two years and yeah, anyway, so beautiful questions, Hala. I would say care is such a major character of this book. Like, in some ways, it's kind of a care adventure book or something. I really am like, I hope that one of the things people notice in the book is that almost everyone is driven by care, everyone who survives is someone who their orientation was like, "Who am I going to care for? How am I going to care for myself? Then who else am I going to care for?" So it's a really big part of the storytelling of the book, like wanting to model also what different kinds of care look like. Like some people almost always go first to community care. So Eloise is like that. There's these women who are like, "We've got a farmer, we've got eggs." There's different people who are like, "We're figuring stuff out for a larger group." That's one of the things that emerges over the course of the book is like her mom was actually involved in helping plan for the care of a post-crisis Detroit. Like care is woven throughout, but that there are different ways to do it. So for some people, the care that they're offering is that intimate hospice care or internal home care, whatever. Then for some people, it's this larger thing. I think we judge each other so harshly right now for where we choose to put our care. We actually politicize it and romanticize it and do all these weird things where it's like, if you're doing a massive organization or a massive volunteer effort or something like that, you're like, "I'm really caring." But then I'm like, "I know so many people who are like in a house every day wiping someone's butt or like helping them get in and out of the bath or helping a child understand how their mind maybe works different from the kids in their class." There's just so many really sweet intimate places where care is happening. There's something, some kind of connective tissue between learning to care for one person really well, even if that person is yourself, and then being able to provide care and be part of a culture or a society of care. So I think one of the crises we're in right now is that people don't really know how to care for themselves without withdrawing from the human project. It's like, "I'm going to go away from everybody and there, I will care for myself and I'll return to this reckless, careless dangerous society and survive until the next time I can do that." It felt really important to me to be like, "Whatever happens next is rooted in care." It's not just the care of the humans for each other but also the earth, the city of Detroit is sentient in this set of stories and it wants to also care for its people, which leads us to the second part of the question that Hala is asking, where this book was a very healing journey for me to take. You know, it was like give myself a fractal, microcosmic experience of my deep grief about the world and how Black people are treated and how anyone we determine to be class is treated, how women are treated, how disease gets responded to, how place is not cared for. There's all these things that are all swirling inside of me as the grief of being a human who wants so much better for us. I think I let my grief, I really let myself be in grief with Dune in that first book. But in my own way, I'm a dissociator, so I will grieve by making something. I will grieve by planting something. I will grieve by cooking something. You know, it's rare that it's just like sitting somewhere crying, but I needed to give myself the care of writing a character who just gets the full room. Then the rest of it is like, "Okay, what is a society I could imagine wanting to participate in?" [laughs] I always feel so disingenuous when people are like, "Yeah, it's like this utopia and like everyone lives in the one house and everyone takes care of each other's everything." I can feel the claustrophobia that comes with most people's vision of utopian society. I always feel bad, like I'm like, "Am I too capitalized or what has happened to me? Is something broken that makes me not want to be all up in the collective all the time?" But then writing this book was like caring for someone like me who's like, "I don't want to be around a billion people all the time, but I do have something to offer. And maybe I could be a leader. Maybe I could cast a spell. Maybe the love that I make, maybe the song that I sing for my dying elder, like maybe these are the ways that I can legitimately weave myself in." And so I felt like I was caring for myself as the book went along. But when it came to Ancestors, that's when I really was like, "Okay, what is my greatest wish truly for what happens here?" I think for anyone, it is a very caring question to ask yourself is like, "What is my greatest wish? What is my greatest hope? What is my deepest vision? What would healing actually look and feel like?" I have to say I went and sat by the Eno River because I was kind of stuck. I had been writing and writing, and I just felt stuck. Everything was still happening inside this boundary of the city that had grown up. The river was like, "You have to let go of utopia or you have to make it so that everyone can be there. Figure it out." [laughs] It was so healing to write the third book with that as my instruction, was like, I either have to let go of the boundary that's keeping them all safe, or have to make it possible for everyone to be here and like, how would I write that? How would I do that? It felt like such self-care to do that writing. Now I feel like I have much more clarity. Like when I think about Emergent Strategy and Pleasure Activism and these ideas, I'm like, "Oh, now I understand more how to bring them into the world through these pockets of deep practice and pockets of like really being yourself authentically in the practices." As I finished, I had the same feeling I had when I finished writing Emergent Strategy, which was like, "Okay, that's like, that's a way. That's a definite way." [laughs]

DN: Well, everyone should hold in their minds what the river spoke to you, because we're moving towards that question slowly but surely in this conversation. I did want to mention just one other thing around care or less obvious forms of care that I really loved, which was Dune’s working through periodically and intermittently in the three books her own shame and difficulties around her changing body. So her body has changed, her diet has obviously changed, her activities have changed. It's unrecognizable to the way she used to be, and she's having to work through a lot of her own internalized biases around what this body is and how to be sexual in this body. I don't know if we've connected to this, but there are also scenes laid in the book with an older mentor who's never been held or seen as a sexual being as an older person. It feels somehow related, them both working through this self-conception and how to move through the world, and how to release some things about a way they might be being viewed.