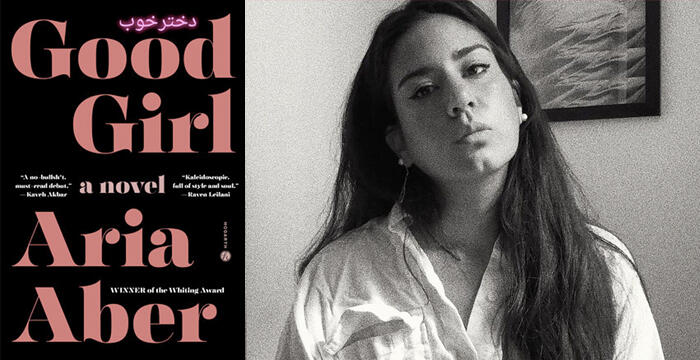

Aria Aber : Good Girl

Poet Aria Aber’s debut novel Good Girl , set in the club scene of Berlin, is a book brimming over with sex and drugs and music, true. But really at its heart it is a book of self-making and unmaking, of self-destruction and self-discovery, where 19 year old Nila navigates the irresolvable dialectics of being a second generation Afghan-German immigrant, finding home neither in the world of her family nor in Germany at large. A book coursing with desire and shame, flight and pursuit, Good Girl is ultimately about the desperate need to find oneself and one’s home, whatever the cost. Where home might not be a place or a people at all, but the world of art and literature itself.

For the bonus audio archive Aria contributes a reading from Palestinian writer Yasmin Zaher’s debut novel, The Coin. This joins Isabella Hammad reading from Walid Daqqa’s prison writings, Zahid Rafiq reading Kafka, Rabih Alameddine reading Fernando Pessoa, Dionne Brand reading Christina Sharpe and much more. To learn how to subscribe to the bonus audio and the other potential benefits and rewards available when you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter, head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today’s conversation.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you by poet Daniel Khalastchi's The Story of Your Obstinate Survival, a collection which Shane McCrae calls "as rich with music as any poetry being written today, a triumph of song." The volume explores trauma through surreal, sound-driven lyrics that marry violence with the absurd, deeply internal, and yet inextricable from the political, this is a thoughtful, musical, uncanny book of poems you want to spend your time with. “With as much abandon as with hope, these poems sway on the edge of a miracle,” Sabrina Orah Mark writes. The Story of Your Obstinate Survival is out from the University of Wisconsin Press. Today's episode is also brought to you by Creature Needs, a path-setting fusion of literary art and scientific research that deepens our understanding of the interdependence between life and habitat, art and science, and the human and the more-than-human world, a collaboration between the University of Minnesota Press and the non-profit organization Creature Conserve, Creature Needs pairs prominent writers from poets Kazim Ali and Danika Kelly to prose writers Aimee Bender and Ramona Ausubel with recent scientific research from which to create their creative work for the book. Whether Sofia Samatar responding to Jaguar Conservation in the Borderlands, or Thalia Field engaging with the effect of wind turbine farms on the health of the side-blotched lizard. In the words of Library Journal, Creature Needs is “A thought-provoking and emotionally resonant read that stands out for its lyrical prowess and formal innovation, making it a significant contribution to contemporary literature as well as a key volume bridging the gap between the worlds of science and art.” Creature Needs is out on January 21st and available for pre-order now. I'll also add, as a perhaps relevant aside that I too am in Creature Needs, and for my prompt, I was given a research study asking whether two different endangered species, the boreal toad and the greenback cutthroat trout could be safely introduced into the same lakes, whether they could be reestablished together in the same space at the same time without interfering with the success of the other species. My resulting hybrid piece, both fiction and non-fiction, one that engages with Sabrina Orah Mark, Donna Haraway, and Ursula K. Le Guin, also looks, I think like the show does, at questions of listening and dialogue, and at the importance of not ignoring the limits and limitations of the ways we devise scientific studies when looking at the results of the studies themselves, to explore as much what is closed down by the questions we ask, what we don't listen for when asking them, as what is opened up by them. In that spirit, today's conversation is about a book that by the author's own framing is one motivated by irreconcilable questions, a book that embraces contradictions and the dialectics those contradictions create. Like the study I was given in the Creature Needs Anthology, Aria Aber's book Good Girl, which follows an Afghan-German second-generation immigrant, 19-year-old Nila, in the nightclubs of Berlin, is also about precarity, about dislocation, about a search for home. It is a book coursing with desire and shame, self-erasure and self-discovery, sex, drugs, violence, racism, philosophy and art, and much more. It poses many questions that question and circle themselves, that generate meaning through staying open and open-ended. I'm excited for you to join us as we circle them together. For the bonus audio, Aria reads from another fellow debut novelist from the Palestinian writer Yasmin Zaher's novel, The Coin, a reading that joins Zahid Rafiq's reading of Kafka, Rabih Alameddine's reading of Pessoa, Kaveh Akbar's reading of his poem In Praise of the Laughing Worm, an epic reading of poems, and then writing prompts designed just for us by Danez Smith and much more. The bonus audio is only one thing to choose from when you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. There are many others, including the Jewish Currents Magazine Bundle, to the Tin House Early Readers subscription receiving 12 books over the course of a year months before they're available to the general public. Regardless of what you choose, every listener-supporter is invited to join our collective brainstorm of who to invite in the future on the show, and every supporter receives the robust resources related to each and every episode of what I discovered while preparing, things we referenced during the conversation, and where to explore once you're done listening. You can find out about all of this and more at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today's conversation with Aria Aber.

[Music]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest poet, Aria Aber, grew up in Germany, has a BA in English literature from Goldsmiths College in London, an MFA in poetry from NYU, and is pursuing a doctorate in English and creative writing from the University of Southern California. Aber is a contributing editor at The Yale Review and an assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Vermont. Her debut poetry collection, Hard Damage, won the 2018 Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry, a poetry debut that announced a formidable new voice, much as Solmaz Sharif did with Look or Layli Long Soldier with Whereas. Solmaz Sharif said of Aber's debut, “Personal and historic, Aria Aber’s Hard Damage traces the multiple displacements faced in the aftermath of violences, national and otherwise. At turns scathing and tender, ironic and keening, Aber writes richly of warfare and Rilke, German and English alike. There is too much barbed beauty for my few sentences to contain, though Aber’s do—elegantly; dangerously. A tremendous debut we are lucky to behold.” Yusef Komunyakaa added, “Aria Aber’s Hard Damage confronts the reader with both a masterful directness and lyrical clarity. Though the poet pays homage to tradition, these poems also realize a voice and experience—truth and sonority, spirit and grit—that are individual. Each turn in this narrative of dislocation dares a root-fed luminosity. Indeed, the speaker of Hard Damage transverses multiple way stations (Kabul, Berlin, Paris, New York City, and elsewhere), always carrying history and family through these migrations. This necessary collection possesses passion and wisdom.” Aria Aber went on to win the 2020 Whiting Award. She's been a Kundiman Fellow and a Wallace Stegner Fellow, and her poems have appeared everywhere from The Kenyon Review to The New Yorker. She's here today to discuss her second book, her debut novel, Good Girl, one of the most anticipated books of 2025. Here are the thoughts on Good Girl from three past Between the Covers guests: Leslie Jamison says, “Aria Aber's stunning Good Girl is a novel that understands home as a heartbeat and a heartache, writing into the ache and daily metronome of exile. It’s a love song and a torch song for Berlin—like an ode to a body full of chronic pain, this is me and it also hurts me. I disappeared into the many overlapping and colliding worlds of this book and emerged with a glistening, vibrating, beautifully exhausted heart—newly alive to the complexities of love and family and becoming ourselves.” Garth Greenwell adds, “Aria Aber’s Good Girl is a novel of overwhelming and conflicted love—for persons, for histories, for artistic creation, for Berlin. Her poet’s eye makes a thermal map of emotional landscapes, lighting up passion, desire, desperate hope, and violence, and showing how difficult they can be to distinguish in the crucible of experience. Rarely has the wildness and bewilderment of youth been conveyed with such richly textured heat.” Finally, Kaveh Akbar says, “Aria Aber’s Good Girl dives heartfirst into one of the art’s great crises: that the great searing ecstasies of youth should form us before we have the psychospiritual maturity to articulate them. Usually writing this good is realized through a gauzy patina of recollection, but in Good Girl the bass beat is still full in your chest, the coke drip’s still a numbing bitter in your throat. Aber’s ear is so remarkably good you hardly even notice she’s building this great symphony of textures, mosaics within mosaics. Seldom has the scald of shame felt so vivid, so lode-bearing, so eviscerating. Good Girl is a no-bullshit must-read debut.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Aria Aber.

Aria Aber: Thank you, David, and thank you for that wonderful introduction. I feel very moved.

DN: To me, there are a hundred different ways one could describe this book and its main character, Nila. You and I are talking before the book has come out, before you've toured with it, and so I'm particularly curious how you will present it ultimately and frame it. I found one brief pre-pub video you did for Hogarth where you introduce us to Nila and to paraphrase you, Nila, a 19-year-old German Afghan aspiring photographer who falls in love with Marlowe, a much older American writer. Together they explore the seedy underworld of Berlin nightlife. But then you say this story isn't just about clubbing, art, sex, friendship, and drugs. But as an aside, I'll say that there are ample amounts of all of these things. [laughter] It's also about violence on both a national level and on a personal level. You did this video with a nice cameo from your cat [laughter] and then seduced us with this amazing Good Girl merch. But all of this to say, I was impressed with how in a really, really brief snippet, you were able to touch on so many elements of what animates the book. But if I were to try to do the same thing that you did, if I were to try to articulate Good Girl as a reader, for me it was about both self-making, which could include the performance of selves and also the unmaking of selves, and also self-discovery, and about how the two, I think need each other, and yet sometimes are entirely at odds with each other. To begin our conversation, I was hoping maybe you could further introduce us to Nila and her situation, the context and impulse that propels this losing and finding of herself. I know this is an impossible question because that's what the entire book is about, but just give us another layer or another step towards what is animating Nila as we begin the journey in Good Girl.

AA: It is a really hard book to describe because it's trying to do all of these different things. I think in order to give it a more theoretical framework, I was really interested in writing about extremes and opposites almost in a dialectical tension with each other. Shame and desire, I would say, are the two catalyzing forces at the heart of Nila. She’s 19 and she lies about where she’s from. She’s of Afghan heritage but tells people that she’s Greek and sometimes other nationalities. At some point, she claims that anything but Muslim is okay because she has an ethnic name and there are only so many ways that can be interpreted. But there are also other types of opposites or binaries that I wanted to explore such as beauty and terror, youth and old age, cultural tradition and innovation, repression and freedom or liberty. Also within Berlin, which is such a diverse and vibrant city that's close to my heart, I wanted to explore parallel societies. On the one hand, we have, of course, the immigrants and the refugees, Berlin houses, one of the largest Turkish populations outside of Istanbul, who are accused by the German society sometimes to not assimilate properly or integrate themselves into the workforce because they are dependent on welfare or are accused of having secret mafia businesses. On the other hand, you have the club scene, which Berlin is famous for, and this really thriving community of techno fiends and dancers who also exist somewhat adjacent to capital because they don't revolve their life around work, but rather around pleasure and hedonism. I really wanted a protagonist who can navigate both of these milieus without judgment and through code-switching and shape-shifting moves fluidly through these worlds. I think it was important also that she's young so that those observations that she provides are not judgmental or overly cynical, but still curious and hungry. The reason why I decided on kind of writing within the tradition of the bildungsroman was because I was so deeply interested in staying with a consciousness over a period of time until the person arrives at a moment or at like this narrative precipice from which there is no return and self-knowledge is gained through a lot of difficulty and I think the most intense period in our lives when this happens is between childhood and adulthood. Truly that moment when something breaks out of you and you have understood that the innocent period of unknowing and naivete may be over. All of these other aspects and themes, such as friendship and art and drugs, are part of her awakening, as well as the political violence in the background.

DN: Well, I don't normally ask guests to read this early, [laughter] but I'd love to have you read the opening to the book if you're willing. Part of why I wanted you to read this early is because I feel like you'll set the stage for us, the tone and the voice and the music of Nila herself because I feel like this will underscore my belief that novels by poets are the best novels. No pressure, [laughter] but I think you will mesmerize people as you read this beginning.

AA: Okay, so this is the first page.

[Aria Aber read from Good Girl]

DN: We've been listening to Aria Aber read from Good Girl. What's interesting, which you've already referred to is that you have a protagonist, Nila, who herself is a fiction maker. She creates this ever-shifting identity with everyone outside of her home. As you've mentioned, no one knows she's an Afghan who comes from a Berlin ghetto. When she's out in the world, she's Greek or Italian or Israeli. She invents a past and erases her own. Yet there is this sense that, to use her words, her hunger to ruin her life, that it's not just a negation of herself, but also a way of finding it. Perhaps the fictionalizing of her life is not only shame but also a mode of discovery. Before we unpack that a little bit more with Nila, your fictional character who fictionalizes, I wanted to spend a little time with your own fictionalizing, with your experience of bringing your own life's concerns into the realm of the fictional, even as Nila shares some broad details of your own life as a second generation Afghan, German, and with parents who share some of the details of your own parents, similar to your poetry collection, and with the acknowledgments at the end of the book, including you thanking the bouncers, DJs, and dancers at various clubs in Berlin, that "allowed you to experience freedom and utopia and abyss," much like Nila experiences those very same things. Even with all this, I don't get the sense that this is autofiction. But I did wonder how you situated yourself to the story in relationship to your own, whether it has always been a novel, if memoir had ever crossed your mind, what attracted you to write fiction, and how writing it differed from how you imagined writing it would be.

AA: That is also such a great question. I actually never thought about writing a memoir. I'm not that interested in autofiction either, even though I love some of the authors who would fall into that category, such as Garth Greenwell and Annie Ernaux and Sheila Heti. I think maybe one day in old age when I'm psychoanalyzed enough, I can look at my own life with enough distance and clarity and maybe pseudo-objectivity in order to make it interesting enough and illuminate my own psychology. [laughter] But for Nila, I wanted someone who was similar to me and yet different enough so that I can manipulate her and put her in situations where I had somewhat of an authorial agency. Even though a lot of the texture and the setting is inspired by my own youth, there are a lot of aspects where we don't overlap. For example, my mother is not dead, I'm not an only child, I didn't grow up in Berlin, I'm not a photographer and I never attempted to be one. That medium of art is also a very different one that I chose for a specific reason because I thought it was challenging to write about but also interesting to bring into text something that is visual and analyze it. I chose the novel because this story or this, I guess, political awakening that I was writing towards for a young person seemed to be too much to bring across just in the world of small poems that are more formally concerned. I did think at some point about writing a novel in verse, however, that would have drawn too much attention to the form, to the breaking of the line. I wanted to maintain a sense of realism for the reader, to spend more time with the story, but also I think there is a big subconscious aspect to writing and the form presents itself to you and you just have to follow it where it goes. In this case, it was a novel. But I've also said elsewhere that I think I have a more novelistic disposition than a poetic one. What I mean by that is that I often lie in my poems too. The emotional truth is there, but I deviate a lot from fact when I write even small lyric poems. Even though I am aware that there is this unwritten or invisible contract between reader and writer and in our post-confessional moment that we're still inhabiting right now in poetry, most oftentimes readers expect everything in poetry to be factually true. So I'm not writing persona poems or anything, but I'm also not necessarily true to the facts of my autobiography if anyone were to check with my parents or my sister or anything. [laughs] So I think it comes really easy to me to create a narrative tapestry that is fictional because I'm interested in atmosphere and place so much. The places that I've inhabited in my real life are often, at least I think, quite boring.

DN: Well, I think you may have answered my next question, but I'm going to ask it and see if we can get another layer of an answer from you. Because five years ago when you were touring for Hard Damage, you said in the Atticus Review, “The parents in my book are loosely based on who my parents are, but they aren’t autobiographical depictions of them or my relationship with them. I tried to create characters with archetypical features for the collection; a wounded mother, a distant father.” Then you add as an example that in reality, you were much closer to your father than how he was portrayed and he was much less of a mystery to the mysterious father in your poetry. You also said at the time that you rejected the idea of honesty in poetry, that you didn't think honest representation of stories is possible in poetry, and that you believed that the lyric operates as fiction. I'd love to hear more about that if you still believe that, but I also mainly bring this up because I'm wondering if in light of these thoughts and in light of your last answer, if you find it easier to be honest in fiction or put a different way, how does your relationship to honesty and honest representation, whatever that means, how does that change now that you're writing a novel? Especially given that at the time you also said, to complicate this question further, that you trust images and sound more than you trust narrative, that the silent mysterious elements of a poem possess a prophetic quality whose intelligence will reveal itself much later to you.

AA: I love that you dug up that interview. I had forgotten that I said that. But what that brings up right now, first of all, is that I did truly look to novels in bildungsroman-type novels, especially when I was putting Hard Damage together at the time, because I wanted an arc to develop for the speaker to start in childhood and end up in adulthood where she looks back at her life and have these, yeah, as I said, archetypal characters to inform her development. That's interesting. I guess there is a narrativist or fictional element to my poetry and there has always been. Honesty is such a hard thing to discuss, I think in terms of writing, especially when it is fiction or when it is lyrical because poetry especially exists in this shadow realm between nonfiction and fiction. A lot of people write nonfictional poetry. But I am very much a writer who's guided by the metaphoric or stylistic devices of language rather than by fact. That's why I can't be a journalist, probably, in a very basic way, because what people say in real life is often quite disappointing to me and I wish they had said something else to drive the plot forward or illuminate the psychology of a certain person better or in a way that I find more interesting. But yeah, one thing that comes up right now for me is an interview that Eduardo C. Corral did many, many years ago that I read where he talked about the lyric and what happened for him when he was putting together or writing his first books Slow Lightning is that once he understood that he could follow the music of the line rather than the truth of the memory, he could really inhabit the magic of the poem, meaning that the poem has its own intelligence and its own truth that you then follow as if language exists in the symbolic realm of a different type of honesty than what might be historically factual. I really related to that. I think I needed to hear that. I read that interview during my own MFA and that unlocked something for me to or unlatched my own relationship to the lyric. I had a conversation from several conversations over the course of my so-called training as a poet, either during my MFA or during my Stegner Fellowship, where other writers who have a different disposition could never lie in poetry. One of my friends, the great poet, Callie Siskel said, "But the poem knows that the name is not Kathleen or the blanket was gray and not blue, so I can't lie to the page," which was so fascinating to me because I think personally, writing was a way for me to inhabit a dream life, one that I couldn't realize within the material constraints that I found myself in as a young person. The page to me is a place of invention rather than just reproduction.

DN: I love that. Well, staying with you in relationship to your imagination and your imagined characters, we have a question for you from Jamil Jan Kochai, the author of 99 Nights in Logar, which was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award and more recently, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories, a finalist for the 2022 National Book Award. Karan Mahajan calls Jamil a once-in-a-generation talent, and Claire Messud said of his latest book, "Kochai is a thrillingly gifted writer, and this collection is a pleasure to read, filled with stories at once funny and profoundly serious, formally daring, and complex in their apprehension of the contradictory yet overlapping worlds of their characters." So here's a question for you from Jamil.

Jamil Jan Kochai: Hi, David and Aria. This is Jamil Kochai and it's such a pleasure and an honor for me to be able to drop in on your conversation today. I actually wanted to ask about Aria's character writing process when it came to so many of these great characters that we see in Good Girl, whether in Nila herself, Eli, Aunt Sabrina, or Nila's mother and father, or even Marlowe, who I love to hate. I guess I wanted to ask first of all about the process of coming up with these characters. But the second part of that question that I think I'm probably even a little bit more personally invested in is having finished the book, were there particular characters that you found yourself continuously thinking about or wanting to return to or even missing in one way or another?

AA: Hi, Jamil. I love that question. I love his writing so much. I'm such a big fan of his work, and it's such a nice surprise to hear him right now. The question of how I came up with these characters is fascinating and again, I think a lot of it is subconscious but constructing Nila and giving her limits and not exactly reproducing who I was at that age was important. I made her less political than I was. At that age, she starts out with a slight disaffection or apolitical nature and comes into it later but is surrounded by these people who have very strong opinions and theories such as Doreen and Eli and Marlowe and even her parents because they used to be activists. She's in this politicized community on all sides but is trying to reject it. In some ways, these characters are inspired or maybe palimpsests of people I used to know at the time, but they served a function in order to create very specific power dynamics between Nila and everyone else around them. Marlowe specifically was an interesting character to write because I instilled into him some of my own opinions about art making within the conversations that they have or about writing, he is the only writer in the novel. That was a fun character to sketch out. I wanted to write a book that has really complex and non-stereotypical Afghan women in it because I had not encountered that in literature before. I'm sure there are books that have that, but my own reading is kind of limited mainly to German and English literature and I was yearning for representation that is both complex, nuanced, maybe even a little ugly, and those are the types of ambitions and tensions that can be included in these characters and female characters that are also strong. That was especially important to me, or how Aunt Sabrina came up as kind of a surrogate mother. As I finished the book, one thing that I realized was that the parents or parental figures for Nila are quite passive. The father doesn't do that much. The mother is dead and absent. Aunt Sabrina and Uncle Rashid serve as kind of stand-ins for a more active or yeah, activated relationship with parental figures for her, which was quite interesting to me. That was not something that I had planned initially. That must have been rather subconscious in the creation of it. But I also wanted to have friendships and friends in the novel because that's something that I feel is missing in a lot of contemporary literature and was not representative of my own experience as a young person. Friends were important just for the texture of the world that I was trying to bring across on the page. I have to say when it comes to the second part of the question that I miss all of them, but I especially miss Doreen, Eli, and Nila, I think. Those three ended up being some of my favorite characters.

DN: Well, I can say that like Jamil, I loved hating Marlowe. [laughter]

AA: Me too. It honestly took me a while to get to a point where I could look at Marlowe with compassion. I think that's one of the secrets of being a fiction writer is that all of your characters are you. Once you allow that to emerge and accept it, they become less flattened probably, yeah.

DN: Well, let me interject just one thing that I learned today in reading, I guess an interview just came out this morning, one of the first interviews of you about the book came out this morning. I learned that contrary to our discussion so far about the ways your life and your portrayal of Nila diverged from each other and the way we're talking about a dream space or an imagined space, you also, as part of doing that, took up smoking again, moved to Berlin. Tell us a little bit about the re-encounter and what that was about for you of re-encountering your younger self even though what you're portraying in Nila isn't exactly your younger self, but maybe some of the energy of that younger self.

AA: Yes. I didn't move to Berlin specifically to write this book. It just so happened that I ended up back in Berlin in early 2020 because I didn't have health insurance in the US. Obviously, we were in the middle of a pandemic. That was a very precarious position for a lot of people. I also was in between visas. I ended up in Berlin and that allowed me to inhabit the story or the sketch and draft of the story that I already wanted and had in my mind but hadn't actually set out to write yet. I was renting this apartment in Friedrichsein, a neighborhood that I'm familiar with, and all the clubs were empty and the shops were shut down. I took these long walks every day and experienced two types of very intense grief. On the one hand, there was this public grief of the pandemic and also the political upheaval of that summer, or the whole year, really, because there was a right-wing terrorist attack in Germany in February, and then we had the summer of George Floyd. Then on the other hand, I was grieving a friend who had passed away in April, and who was very important to me during my own party-girl era, so to say. The interesting thing about fresh grief especially is that it's so vigorous and actually makes you feel more alive. I think Sheila Heti has a sentence about that in Pure Colour where she talks about how grief didn't actually numb her down or gray down her perception of the world but opened her up to it and that's exactly how I felt as well. I felt as though all the doors of perception had been opened and I was inundated both by my own memories but also by all of these sensations that I was having while walking through the city. That allowed me to bring a really embodied experience into the writing of it. I did start smoking again. It is true. I think partly it is because all my friends in Europe still smoke real cigarettes. On the other hand, because listening to a lot of techno music made me nostalgic in some ways and allowed me to re-inhabit a younger version of myself that could remember what it was like to be that excessive and be that hedonistic because I did leave that lifestyle behind. It was a fascinating experience. I wrote the last three or four chapters of Good Girl during that time. They emerged in, I would say, deluge out of me and they almost are still exactly the way I wrote them during that first draft. Then I had to figure out over the next couple of years how to get the character to where she arrives at the end, which was a complicated endeavor and quite different to writing poetry because I've never started a poem at its end, but always rather at the beginning and I'm surprised by where it takes me.

DN: Well, moving away from you in the world versus you in your fiction to Nila in the world versus Nila at home, I'm heading over the next question to past Between the Covers guest, Megan Fernandes. Megan's the author of The Kingdom and After and of two collections with Tin House, Good Boys, which it feels like should be shelved next to Good Girl, [laughter] and her most recent book, the one that we talked about for the show, the amazing I Do Everything I'm Told. Poet and editor of Poetry Magazine, Adrian Matejka says of this book, “The collection is, at its center, a book of love poems like all the best poetry collections are. The pretense of love, the past tense of love, and what we do when the little galaxies we build with others start to come apart. Fernandes navigates these spaces with the kind of slick wit and care that love poems require: awareness, eros, and utter abandon.” I just have a totally random aside, but as I was poking around to write this intro for Megan, I stumbled across a course description for a class she's teaching this spring at Lafayette College where she shares an anecdote that I loved, which has no purpose but I'm going to share it anyways. I mean it has a purpose but not for this question. Quote, "A French professor in college once told me about a conversation between the famous impressionist painter Degas and the symbolist poet Mallarmé. Degas told Mallarmé that he wanted to write as well as paint. He said that he had some great ideas for poems, but he could not seem to articulate them when he sat down to write. Mallarmé responded: ‘This is because you don’t write poems with ideas, but with words.’” So with that, here's a question for you from Megan.

Megan Fernandes: Hi Aria, it's Meg. I'm so excited to ask you a question about Good Girl. I've read the book twice now. I love it so much. Congratulations. My question is about the sort of genre of coming of age and the character's journey towards self-knowledge. There's a lot of restraint in this book in terms of what the character is willing to say about herself to this emerging subculture, if we want to call it that, in Berlin. There's also a lot of indulgence in drugs and nightlife. There's this great tension that you are working through in the book between restraint and indulgence. Yeah, I guess my question is about what does the character learn about herself? What was surprising to you as the author about what the character learns about herself? Also, is this also a book, a little bit of a revenge book in the way that a man is kind of used as a plot device towards a woman's self-knowledge and ultimately self-sovereignty, not to give too much away, in a way that a lot of bildungsroman books men are using women that way? You've done that in such a great way without flattening any of the characters, which we cannot say the same thing about some of our esteemed male authors. So yeah, whatever from that you want to talk about; self-knowledge, what the character learns, what surprised you about how the character learned, and also maybe something about the relationship between restraint and indulgence in that sort of process of self-knowledge.

AA: Hi, Meg. I love her. It's so wonderful to hear her. What a nice surprise again. Before I start answering the question, I think that actually both of the poetry book titles that you just mentioned exist in a similar realm as the title Good Girl. I Do Everything I'm Told is another one that is related to it. Okay, so I guess that those were two or three questions. To answer the first one about indulgence and restraint, I think I can loop back to what I said early on in the beginning that I was interested in writing about extremes and about opposites, and specifically about these two forces of shame and desire with Nila. She is ultimately driven by the sense of eros or the life drive down a path of filth and excess and the restraint that is cultural because of her Afghan family and is imposed upon her. She obviously wants to break open, rules are meant to be discarded or meant to be exploded really. She thinks that self-destruction or self-erasure is the only way to do that, even though it allows her to encompass a journey of self-fulfillment, which is this dialectical tension that I am interested in, in particular. But the shame that she's so often trying to outrun catches up with her eventually and then leads to a sense of withdrawal, isolation, self-hatred. As a narrative device, it was so useful for me as an author to use shame to illuminate her inferiority, her psychology, her inferiority, inferiority complex, and her neuroses, but also to, I think, elasticize the narrative, slow it down a little bit. Every time she has a conflict with another character that makes her feel ashamed, I could include those childhood chapters that reveal something to the reader about her background and underpin the present-day narrative with the past, even though the past is still full of lacunae and questions because she doesn't know what her parents' life in Afghanistan was, but we do learn more about her childhood that way. I was interested in indulgence and shame and how they work in the novel or how they work in Nila's life in particular because shame was something that I grew up with. Afghan culture is a shame-based culture and there is something extremely biblical or Abrahamic about it. The way shame functions I think actually goes back to the fall from Eden and Adam and Eve suddenly becoming aware of their nudity and hiding their genitals with fig leaves or whatever and especially shame as related to the nude female body and what her genitals represent or what kind of desire they might lead to is something that Nila is especially interested in and driven by and feels complicated about. Then the second question about it being a revenge book, I love that interpretation. I had never thought of it that way, but I guess it does function as a revenge book in some ways because it is so extremely feminist. But in reality, the male characters that I was more invested in or more invested in exploring Nila's relationship to was not Marlowe, but the men in her community. I think the irony here is that Nila assumes that she's suffering this extremely singular fate because of the patriarchal rules that she's trapped in, imposed on her by her family. But what she learns later on in the novel, I think, is that the male members of her community are also suffering from a kind of restraint imposed onto them by the German society because men who are Afghan or Muslim or read as Arab are often seen as a threat or as a terrorist if they don't castrate or emasculate themselves. They're also not liberated in this world that they're inhabiting together. What was most surprising to me in the novel or in how Nila's self-knowledge emerges, I think the most surprising aspect was how she arrives at this understanding that I just spoke about as under as understanding herself as part of a larger collective or a group or empathizing with the men in her family that it happens via a photograph that she encounters. This photograph that I describe, a little backstory to it, it's a photograph of Nila's father and his cousins and some of his brothers on a hill in Afghanistan. They wear kofias and Afghan dismal shawls on their shoulders. One of them holds a camcorder. But Nila thinks in her memory that it's a rifle and this is something that actually happened. The photograph just came up as I was writing it and it's a real photograph that I have and during revision, I went to look for it and then I realized that it isn't a rifle but actually a camcorder. I'm not exploring this so much overtly in the novel because it almost seemed like a cliche of my own subconscious that this happened but that was probably the most surprising little slip in terms of writing it, yeah.

DN: Well, it feels like there are innumerable reasons we could give for why Nila creates an alternative identity out in the world. I think part of it is, as Megan alludes to around the simultaneous restraint and indulgence of Nila, the coming of age, or a coming into self-knowledge for sure. But I also think about the racism that is the totalizing weather of Good Girl. There are neo-Nazis living next door, her teachers probe her about whether her father is involved in al-Qaeda, she's called Jew Nose in school, neighbors refer to her family as orientals, swastikas tag her door. But we also get a regular drum beat throughout the book, usually in the background, mentioned often in passing about a Syrian bakery being burned down or a Turkish girl being stabbed or a Turkish flower seller shot in his shop or a market being burned down because people think the owner is Muslim but when he turns out to be Greek, the mayor of that German town's responses we didn't know. Or at one point, Nila repeating a line from Michel Houellebecq's novel, Platform, “Intellectually, I could feel a certain attraction to Muslim vaginas,” where Nila goes on to say, "This is the representation I saw of myself in these books everyone lauded in my youth, a disgusting, hairy cockroach of a being uncultured and uncouth, barely good enough for sex." Before I make this into a question, as an aside and out of curiosity, you've mentioned in interviews about your poetry collection Hard Damage that your own childhood in Germany was one of both subtle and overt racism in a school environment that was very wide and you felt you didn't have the language to define it as it was back then. I'd be curious to hear about the absence of language around that for you. But also, while I would never presume to imagine that being an Afghan in the US is any better and it could even be way worse, I'd be interested in hearing about any differences around the othering and racism as it manifests in Germany versus the United States too.

AA: I think in part it is easier to live in the United States as someone who looks like me and has my name because I can pass as ethnically ambiguous here, whereas in Germany, I am definitely the most othered kind of person and no one would mistake me as ethnically ambiguous. People think I'm either Arab or Turkish, which is a very different experience than being in the US. Part of the reason why I chose to set this book in Berlin and not elsewhere was in order to illuminate exactly that tension. There is a moment later on in the novel where Nila has a Somali co-worker and witnesses her experiencing some kind of racist joke which puts into perspective her own so-called privilege that there might be people for whom the racism in Germany is even worse than for her, but she doesn't have the kind of understanding that I think an American person would have because race here, when you talk about racism, I think the first thing that comes to mind is the racism against African Americans or Native people because that is part of the cultural and historical fabric here. It really depends on the context that you're in. Within the context of Germany, especially with the Turkish guest workers who came over in the 70s and in the 80s in State, the other, the big other is someone who is from the Middle East or from the former Ottoman Empire. I wanted to write about the NSU, The National Socialist Underground Organization, which is a real terrorist cell that existed and now exists in a second iteration, because their violence against Turkish immigrants started before 9/11. It was just interesting to me to gesture at how deeply seeded that form of xenophobia and violence is in German society, even though they pride themselves on having rid themselves of it through this very excessive and prominent memory culture. Yeah, so coming to America for me was a way of experiencing a kind of ambiguity, a kind of freedom, even though that word is very weighted and at the moment that we're in right now also doesn't necessarily translate as a real freedom. But yeah, there is a kind of claustrophobia that I do live through when I am in Germany. The lack of language around it, I think has to do with the fact that I wasn't versed in critical race theory at all, but also didn't know how to articulate it because I grew up in a very culturally rich household right at itself and being educated and privileging education and I was sent to a very good school and my parents are not first generation or even second generation academics, all the people in my family have a college degree. In some ways, class is the main concern for Nila, but she also doesn't have the language for that in the book either. I guess I asked myself this question at some point after finishing the book, would have Nila lied about where she's from if she had been from a rich family? I think the answer is no. Even though the racism and all these microaggressions and this othering leads to this very severe form of shame for her, so that she lies about where she's from to all these people around her, I think ultimately, the source of her shame is poverty and this very material lack and disenfranchisement. One other thing that I wanted to mention which we haven't spoken about yet is that she doesn't only lie to the people outside of her home about where she's from, but she also lies to her family about what she does. She leads a double life and wears a mask at all times. There is this sense of impossibility of being herself in all ways, even at home.

DN: Well, to stay with this question of class, for every drug taken in the book as a refuge from life or as a pursuit of life with lines like, "We snorted speed to stunt the ecstasy, drank some wine to stunt the silence, then collapsed side by side on his couch and smoked about a thousand cigarettes." For every line like this, there seems to be just as many mentions of insects in this book: Spider ants, bees, carpet beetles, flies, or lines such as "like cockroaches we scurried through our district." And later I want to more fully talk about Kafka's presence in the book, but for now I will just read the epigraph from Good Girl, which is from the Metamorphosis, “Was he an animal if music could move him so? He felt as if the path to the unknowable sustenance for which he yearned was coming to light.” This feels like the perfect opening to the book, honestly, as it is through the music at the clubs, the drugs, the culture where she is seen as human or more human, not a ghetto-dwelling unwanted immigrant. But it seems, as we've already sort of explored, a devil's bargain in so far as so much of her family dynamic is one of shame. Some of this is very deeply informed by being a second-generation immigrant, I think, in a general sense, embarrassed by her parents' inability to communicate in German, or even when she's 10 years old, she saw herself as the adult in this regard, translating and correcting their grammar. But the other part is the parents themselves are also ashamed of their fate saying, “We had a normal life once.” It was one where they were educated middle class professionals in Afghanistan, but they can no longer do what they're trained to do in Germany, where multiple family members now drive cabs. I couldn't help but wonder if one part of Nila's shame was not just or only not wanting the predetermined fate of her people in Germany, but also the witnessing of her parents' shame at their own diminishment. A shame which suggests an otherwise that Nila never experienced, a before and an otherwise. The dynamism it must have had, the activism they participated in when they were in a country where they actually thought their actions could change the place for the better, unlike Germany where they're not even in a role where they could participate in the national culture in that way.

AA: I think, in part, the shame that Nila experiences is hyperbolic, excessive, and very solipsistic and only related to herself. But then, in some other ways, it's also an inherited feeling that she absorbs by her family, witnessing them, being aggrieved about what has happened to them, about the class that they have pummeled from, and the impossibility of transcending that in the new country and how much pressure is put on her to do it for them and lend them a hand upwards. In some ways, Nila has never had the ability to be a child fully, even at the age of 10 or 11, she has translated government documents. She has the privilege of being fluent in the language of the society that they're in, which her parents don't, which allows her some flexibility, but also puts a lot of responsibility onto her. She assumes the role of the adult, which is not a fate that is singular. It happens all the time. It happens in the US. It happens everywhere, I think, in exilic or diasporic communities. But I also think that as with the class anxiety or the class shame that she experiences, one of the other main wounds within her is the wound of exile. As Edward Said says somewhere, exile becomes the defining factor of your subjectivity, if that happens to you, the impossibility to return to the original country. Of course, that is different and much more material for Palestinians than it is for Afghans. But if you look at how long Afghanistan has been occupied for by different empirical forces and now by the Taliban, which some of the Afghans in the diaspora or even within the country think also of as an occupying force, I think it translates to a similar melancholy condition for the people, this absolute lack of origin or a country or unity with a native landscape, which she has inherited. I think she's very young still so she might not understand that she exists in this third place of being neither from there nor from here, but might experience a sense of solidarity with other people in exile. A couple of times, I am hinting at that in the novel with the character of Setareh or Eli, but it is also true that apart from shame being this repressive force that is used against women within her culture, there is also the melancholic shame of her parents about what has happened to their lives and their fates and the material limits that they brush up against over and over again. Yes, I think it is also familial and shared and something that she has been taught by them. By other people, I think I mentioned an encounter in the novel where a girl in her neighborhood lies about being Colombian and not Iraqi or something. It's not just something that she does, I think lying about where she's from or fabricating a different kind of reality, but that other people in her community do as well. That is something that I experienced in post-9/11 Germany a myriad of times. That was quite fascinating to me growing up.

DN: Well, both of your books allude to parents with activist pasts. Both have mothers who knew the revolutionary Meena Keshwar Kamal. You have a poem dedicated to her. The mother in Hard Damage went to prison as a political prisoner, political prisoner because she believed in women's rights. One passage in that book that stuck with me goes, “Today the editor in the white shirt asked me, 'What printing device did your mother use?' And I think that's when I saw, really saw for the first time, not the prison, but the thing preceding it. A basement cluttered with paper, drabs and ink, the city peeled completely white, her black hair curled with soda cans, printing the magazine that fought the government, and it occurred to me that she was beautiful.” All of this made me curious who Meena is to you and your family and how her philosophy relates to that of you and your parents before they were parents.

AA: I love that question. Thank you for that. Well, Meena Keshwar Kamal is someone that my family knew, especially my mom's side of the family, they were all activists, they all went to political prison. They started being activists with different socialist groups, but eventually, the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan, (RAWA) was founded by Meena Keshwar Kamal. My mother and her sisters and some of her brothers also joined them and they did print the flyers and the little magazines or journals that they did in their basement or actually I think it was their attic and ended up in political prison. My mother was there for two years and I was raised with that kind of Marxist or socialist philosophy in the house. It was very much present. It was one of nuance because it's anti-empire on all fronts. They were anti-Soviet and anti-US, but still believing in a socialist politics. Some of them were Maoists at the beginning, even though that also started to deteriorate eventually as it so often is for the leftist groups and infighting that happens. But yeah, she was this kind of cipher and icon that I grew up with. We had pictures of her in our family albums and all these stories that I grew up with and people who used to know her and were inspired by her. The women in my family would bring her up as the martyr who had died so that I could have the kind of freedom that I wanted and the life that I wanted. She has always been a real source of inspiration for me, especially because Afghan women are portrayed as these repressed burqa-wearing figures in Western media. But the reality of it was different, at least for me.

DN: Well, like in so many immigrant families, there are all these divergent stories of how different lives in Nila's family either flourish or fall apart after their dislocation and arrival in a new place. Nila locks on to certain stories as inspirations, and I was hoping you'd read another section for us that contains some of these family stories.

[Aria Aber read from Good Girl]

DN: We've been listening to Aria Aber read from Good Girl. One paradox in Nila's psyche is that just after this passage that you read where she asks, “Why can't I be free,” where she wants to reject her life and all its various compromised paths entirely, and she describes it as if every cell in her body was screaming “I want to live,” right after this, she expresses the allure of her parent's life before, which I suspect she imagines as one that coheres and makes sense, where counterintuitively she says things like, "I envied the orderliness of religion - how easy it seemed to have a set of morals to adhere to, a set that connected you to the higher essence. Stupidly, I daydreamed about a version of reality in which we were God-fearing people and my heart would be pure. If you believed in God, maybe we wouldn't live here anymore,’ I said to my mother once. ‘Well, try praying harder,’ she said to me, ‘if that's the way it works.’ The religious families seemed happier to me, calmer. Their homes were always clean. They looked like they didn't fight, had mothers who were content with their homemaker roles, not as conflicted as mine, torn in two by a repressed need for liberty and the desire to be loved by her husband. She didn't leave my father, because unhappiness was not a reason for women to get divorced. Everyone was unhappy.” As you've talked about this dialectical aspect of the book, I really love this polling from two extremely different irreconcilable directions. I think of Bhanu Kapil's book, Schizophrene, which is partly a look at the relationship between migration and an increased incidence of mental illness, which has lines like, "Nobody is emigrant. All trajectories are psychotic in the reliance on arrival." In one of its epigraphs from Adorno, “It is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home.” I'm definitely not suggesting anything psychiatric with regards to Nila, even as she describes herself as having the "illness" that Nadia had in the passage you read. But rather she's in a situation with no arrival and no home in many regards, one that produces this curiosity about if they were God-fearing, and yet one that also romanticizes the family members who've escaped things entirely, that aspect propelling her into the clubs and a sort of obliteration of self-through-drugs. I guess I wanted to hear more or have you speak more into this irresolvable split that is happening not only in the book, but literally these two passages side by side, the one you read and then the one I read after it.

AA: I do think of her as a deeply paradoxical character who embodies extremes and whose sense-making is deeply disturbed. Yeah, I like the idea of being split subjectivity, a split consciousness that emerges out of exile or the exilic condition. There is probably something deeply psychiatric about this book. I could pathologize her or the other characters. There is the sense of PTSD or trauma that disrupts I think the narrative of people in the diaspora or exile in general because it prevents a sense of temporality or linearity and leads you to loop back to the past. The past is always overshadowing the present or catching up with it and creating these ruptures within the self, but also within place. I think I was thinking of emerging out of ruins and what that might look like for a young person like Nila, the shards of her family, that some of them she can touch and see in the forms of her parents or photographs she has access to and a lot of them that she doesn't have access to and that exists in this unstable realm of the oral tradition of stories that she hears and stories that other family members tell her. Her relationship to religion is extremely conflicted because she is existing within a family structure or within a nuclear family that doesn't adhere to any religious rituals, even though maybe the prior generation or other people in the extended family do. That leads to a sense of confusion for her, because she doesn't understand why then without God or this overarching spirit that would exist in a vertical space, she still has to adhere to the rules that are related to religion or come out of religious tradition. I think she just yearns for something, for a structure that is stable and which she can't find in her family because they are also—at least the mother and the father in some sense—adolescents who are still trying to square what rules to keep and which ones to discard and how to marry their own values within the values of the larger community, because everything is so based on reputation and image, and she rebels against that. I love the passage that you read out loud because it is deeply ironic. I don't think Nila would have adhered to any types of rules within a religious family either. She would have probably broken them too because she's driven by this insatiable hunger for all kinds of experiences. But what that speaks to, I think, more deeply is that she has this yearning for spirituality and for becoming one with something higher and bigger than herself, which is almost mystical in nature, I think. She ends up finding a version of that in the club scene, ultimately through the use of consciousness-altering or expanding drugs, and those allow her to experience a sense of the solution of boundaries between self and other. That is ultimately, I think, what she desires.

DN: Well, that's a perfect segue to my next question. I wanted to spend a moment with purity in relation to goodness, with Nila's favorite story in the Quran being Gabriel taking out Muhammad's heart and washing it in the snowy waters of the Zam-Zam. She too wants her heart to be cut out by God and washed. She desperately wants to be good, but in the mornings her yearnings for God quote, "like every true thing she had ever felt embarrassed her." Even in her life with her much older white American boyfriend, Marlowe, who says, "It's Deleuzian, really. We’re small machines trapped in the big machine of capitalism, and techno can defamiliarize this existentially fraught condition," Nila, on the other hand, in contrast to poststructuralist theory, believes in some sort of a priori truth, or wants to at least, in the goodness of God. You've talked about your own family having a wide spectrum of relationships to religion. You've talked today about your mother's side, which you've referred to in other places as atheist and often mocking of religion while your paternal grandmother was an old-school Muslim, using your words, and that you reconciled with spirituality and God within your own heritage using mind-altering drugs and ayahuasca ceremony in Peru. I know that's probably very personal. I don't know if that's something you'd feel comfortable talking about. But either way, I wonder if you could speak a little more into these questions of purity and goodness, badness and ruin, which get expressed in her love relationship in this very abstracted philosophical debate. But it's also this sense of a priori goodness, it's sort of like the irretrievable Afghanistan too, I imagine.

AA: Absolutely. Yeah, I do think that Afghanistan or the place or the moment before exile became a reality for this family for Nila does exist in this almost platonic ideal place in her mind that she can't return to, but that is one of unity and wholeness. Now she lives in a fractured world and yearns for what I just said, stability and security in some sense. Goodness is really interesting to me. Again, I think in a dialectical sense, because there is another chapter in the novel where she talks about suspecting that goodness or purity could also be found in an excess, which is also, I guess, when you look at the history of ancient religions and how they have used mind-altering substances or still use to this day and certain rituals, also a way to encounter the divine or the absolute essence that encompasses us all. My own relationship to spirituality is really pantheistic, maybe related a little bit to Spinoza or lying somewhere between Rilke’s understanding of God and Spinoza’s understanding of God that God is everywhere and transcendent or immanent within nature and we all have a molecule of it within us. In some ways, I can’t control what I believe in. This is something that I've always felt, even though, as I said, I wasn't raised with any traditions within my very private household. I was sent to a Catholic school that is similar to the school that Nila goes to in the novel. I did have these two traditions, or a set of references to fall back to every time I experienced something disastrous and that made me yearn for God, which was either Catholic prayers or Muslim prayers. I think ultimately they're just different lenses through which you can look at the same thing. I also experienced religious ecstasy or a kind of mystical relationship with the other realm in my personal life. For sure, during experiences that included a shaman and ayahuasca or other types of drugs, but within the realm of the novel, I wanted Nila to yearn for that type of revelation and not achieve it, so that there is a boundary. Every time she is close to having an encounter that could be related to religious ecstasy, I think something prevents her from achieving that type of unity. That was a tension that I was interested in exploring within the book. Initially, there was a chapter included at the end, preceding the breakup between her and Marlowe, which is now taken out of the book, where I had a long meditation on this encounter with music, which related to the epigraph in the book. Nila did experience a kind of religious unity with everything, but I decided to take it out ultimately because it was more interesting to me that it remains unattainable.

DN: Well, I had two questions for you about your life post poetry collection or post Hard Damage. One is that you wrote Hard Damage before you yourself had visited Afghanistan. When you did ultimately go to Afghanistan for the first time, you've suggested that if you had gone before you wrote the poetry, that the book would have been quieter, less angry, and more restrained. You've also said that after going, the sense of lack or the sense of absence didn't resolve and that you couldn't write for a while afterwards. When you were on the VS Podcast, you said to Danez and Franny that going to Afghanistan disabused you of it as your home. You related it to Solmaz's last trip to Iran, where something shifted for her too in this regard. Danez then talked about going to Nigeria and feeling grief. It all made me wonder given that Good Girl I'm imagining is written at least partly after going to Afghanistan, how going to Afghanistan, how you see that manifesting in this book versus the previous book living within an imagined sense of Afghanistan.

AA: I love that question so much. I definitely wrote all of the book after visiting Afghanistan. Perhaps venturing into prose allowed me to inhabit a little bit of the fascination and the anger about being in exile that I had explored in Hard Damage because Nila doesn't have access to that country. She doesn't have a firsthand experience of the landscape, so it still exists within this realm of imagination. But I could voice my own experiences or the knowledge that I gained while being there, which is a kind of grief, but also an alienation from that place through the character of Sabrina, who then tells her that she actually doesn't know a lot of the things that she feels angry about. I could explore that tension within the dynamic between them and fictionalize and dramatize it a little bit. At the same time, my next book, I'm writing two books right now, one is a poetry collection, and then the other one is a fiction book, a novel again, the novel is set in the 80s in Afghanistan, actually, and has a character who returns after some period of being away, which I hope will finally allow me to write about it in more clear way, I think, as from what I have been able to do until now, because I think I just had to restructure and reconfigure and reintegrate my relationship to language and what propelled me to writing in the first place after I visited Afghanistan, because I just assumed that I would feel ultimately at home being there and that didn't happen even though I experienced a type of linguistic intimacy with that place that I had never ever thought was possible because suddenly everyone around me was speaking the language of my home which felt so private to me and I almost felt naked but not in a bad way that would make me feel ashamed, but rather like relieved almost. It did feel like a return in the sense of language, but it felt extremely alienating in all other ways. It took me a while to recover and stitch my own subject to it back together afterwards.

DN: Well, my second question that comes from looking back at Hard Damage is how you've mentioned in various places, including the VS Podcast and also your interview at the Poetry Foundation website called Homesick for an Imagined Place, you've said that you feel like your first book was appropriative of experiences in ways that you wouldn't do now. You say explicitly within the book about the mother figure in that book, that her wound is not mine. But at the same time, it does feel like some aspect of the mother's wound is the daughter's wound too. There is that dialectic too, I think. But could you talk a little bit about what you would have done differently looking back, regarding experiences you didn't live or and/or, if the shift in position for you, around what you feel like you should or shouldn't portray, and from what point of view, if that played a role in any of the choices you made in writing Good Girl?

AA: That is such an interesting question, and I am going to contradict myself, because earlier I said that I would never write nonfiction, but I think the only way to have written about other people's experiences without appropriating them, from my point of view, would have been to allow their own voices to enter the page through maybe a nonfiction collage the way Svetlana Alexievich does it in Zinky Boys. I still dream about maybe writing a book in that vein one day. It didn't really manifest in any real way, I think, in the writing of Good Girl other than creating these other characters who have experiences and life knowledge that Nila doesn't have and chastise or reprimand her for assuming certain things. I think it allowed me to illuminate the idiocy and naivete of a young person through the family dynamic that is portrayed in the novel.

DN: Well, we have two questions for you that are variants of the same question, and it's also a question that I also share with them, so I'm going to play them back to back, and then also piggyback myself onto their questions for a triple-headed question before you answer. The first two parts of this three-headed question are from Kaveh Akbar and Fatima Farheen Mirza, Kaveh who appeared on Between the Covers’ first poetry collection Pilgrim Bell, most recently published, like you, their debut novel, “Martyr!” which Karen Russell said is one of the greatest novels she has ever read and which was shortlisted for the National Book Award in Fiction. Fatima is the author of the 2018 best-selling and critically acclaimed debut novel, A Place for Us, of which Ron Charles for The Washington Post says, “She writes with a mercy that encompasses all things. Each time I stole away into this novel, it felt like a privilege to dwell among these people, to fall back under the gentle light of Mirza’s words.” Here are their questions for you.

Kaveh Akbar: Hey, Aria, congratulations on the release of this beautiful book. Hi, David, thank you for all you do for authors and readers, for books writ large. My question for Aria, writing the novel, you also did your own translation for the German edition. It's kind of your debut volume, both as a novelist and as a translator of a full-length book. I know that you've done individual translations. Can you talk a little bit about translating yourself and being a kind of double debutee? Thanks.

Fatima Farheen Mirza: Hi, Aria. I loved your book, as you know. I wanted to ask about your experience translating it yourself into German, especially because German is one of the languages of your childhood and it might even be the language that Nila is experiencing her life in, and yet you wrote it in English. I wondered what that was like writing it first in English and then later translating it into German and if there were any sections of the book that felt more alive and one or the other or perhaps more confronting to you or more emotional to you or even if there were certain emotions that felt more present in one language or another. I was thinking about the sense of freedom that Nila has in this book and also the sense of shame and I just was curious about your experience as you were translating and writing it.

DN: Hi, Aria, this is David Naimon, host of Between the Covers. [laughter] I'm amazed, like them, that you essentially wrote this book twice. Similar to Fatima, I wondered if you noticed anything about Good Girl's personality being different in German. For instance, when you say in Hard Damage that the first person singular pronoun in German is not capitalized, you ask, “Is my German self-hood humbler? Does it fold into itself?” I'm also curious how faithful did you feel like you had to be to this so-called original. I say so-called original because, in this strange way, you wrote the book in your third language and then translated it into the language you grew up in, a language you are closer to, the language of your formative years. So, in a weird way, you could make an argument that the German, though it hadn't been written yet, was the original. I could imagine you envisioning very different audiences, both audiences you know very well, which who knows, perhaps, could make you make different choices in how you render those sentences. Does one version feel more honest or vulnerable than the other?

AA: I love these questions. I guess I can go back to my decision as to why I started writing in English in the first place. English to me, I went to bilingual school also so it was there in my education and very present, but I didn't start writing in English until my early 20s when I think the second year I lived in London and was doing my English literature degree there. But it allowed me to be more playful and a little more liberated from the strictures that I experienced in German. Even though German is the only language that I don't have an accent in and feel most comfortable in, it felt like the oppressor's language. I know that this is factually untrue because German did not colonize Dari. Actually, if you think about Afghanistan, it's rather that Dari is the colonial language over Pashto. Nonetheless, because I grew up as a child of refugees in Germany, it felt inhabiting this oppressive force because it was the language of the government and the language of bureaucracy and education. I always, like Kafka, felt a little bit like a foreigner within that language, even though I mastered it pretty early on and do feel at home in it. There was always the sense of conflict that I experienced between Farsi and German. Moving into English, into this unknown territory, allowed me to reinvent a sense of self as a writer that was not overshadowed by I think the grief that German has for me, and also allowed me to be extremely innovative in the way I construct my sentences. I love English because it's both Germanic and Latinate. You can use words like sybaritic without it sounding strange. You don't have that in German because it's such an earthy language, even phrases that are borrowed from philosophies such as "estrangement" or "alienation" are just "verfremdung" in German. So they're a little more pedestrian in a way, a lot of the phrases that I so love in English, and that you can't just use without it sounding absolutely bonkers or extremely pretentious in the German language. It has a different kind of texture to it. Yet at the same time, this is a little counterintuitive, but English feels more musical to me because the grammar is slightly more paratactic than German syntax, which allows me to be more fragmentary in my writing, and also to break many more rules and be free about it and not feel as attached to, I think, the idea of correctness. Because English functions as a lingua franca and has been altered and affected by all of these other dialects and languages around the world, it just feels like a more flexible medium in which I can write. I decided to make Nila an adult who looks back at her own life at the very beginning of the book so that I could situate her also as a foreigner, as kind of like a minor speaker within the language, so that I could explain some of the estranging choices that I make linguistically, some of the overt lush textures and the musicality that I saw relish in while writing. Bringing that across into German was an extremely difficult task, I have to say. It does feel like I have rewritten it, even though I still believe the English is the original, the true original. But I had to honestly sacrifice a lot of the music for it. I remember my sister read an early draft of the novel and my sister lives in Germany and she knew that I would start the translation very soon and she was already quite sad about it because she understood that I couldn't quite replicate the exact musicality of it and there were some words that I tried to keep or some foreign loanwords that I then chose from this old dictionary that I used while translating in order to bring across some of the strange texture that I have in English into German and my German editor refused to accept those, which was a funny experience. [laughs]

DN: Oh, wow.

AA: But I kept capitulated to the fact that, yeah, I do want it to be readable in German and not too opulent. So I just had to accept the constraints of the target language in this case. But a little bit of a fun background tidbit is that I did write two of the chapters where they're at the festival in German first.

DN: I love that. Yeah, that's amazing.

AA: Yeah. So those were actually retranslated into English and then translated again into German.

DN: Yeah. Well, when talking about Hard Damage, you said, “In a way, writing in a language that is not ‘my own’ and not ‘my family’s’ works as a shield from their eyes; it provides me with more liberty. English is a room in which I can dance and scream and laugh in whichever way I like.” I love this because it feels like it mirrors Nila's desire for a third space as well. Not a linguistic space in this case, but not her family space, not Germany space, but this space to dance and scream. It doesn't come as a surprise that many of the writers that you cite as important to you also work in a language that isn't primary for them. In the book, there is this line about Nabokov, “The poetic intensity of his style stemmed from the fact that he was exiled in English; that he excavated the strangeness of English because he was a foreigner in it.” You've described your first book in this way, that there was a lot of sonic play more so than later on because you were back then looking at English from the outside. That book also opens with the line, “Into English, I splintered,” and later, “To miss my life in Kabul is to tongue pears laced with needles.” I also think of your essay in Jewish Currents when they had their Paul Celan portfolio, who's one of the formative writers for you, where you say, “When we studied Celan’s mysterious, hermetic poetry in high school in my small, Catholic German hometown—where the people I felt closest to were the dead, and where, lost and lonely, I sought refuge in notebooks and soft paperbacks of modernist literature—I felt a door open in me: to the possibilities of language, and, in particular, to the political dimensions of writing in a language in which I, as a foreigner and child of refugees, felt displaced and alienated. Celan helped me imagine a home in poetry by showing me that one can defamiliarize the world of words.” Then you go on to explore Celan's poem Speechgrille and how the title in German comes from the word for these medieval barred windows from which nuns were to speak from, from their cloisters. They had these gothic screens hung with cloth and studded with nails to make touch and eye contact difficult. This becomes a vision of Celan's own adversarial relationship to the language he's making his own art in as a Jew writing in German post-Holocaust. I just wondered if this sparked any further thoughts for you about him, about that poem, or more generally about English and German.