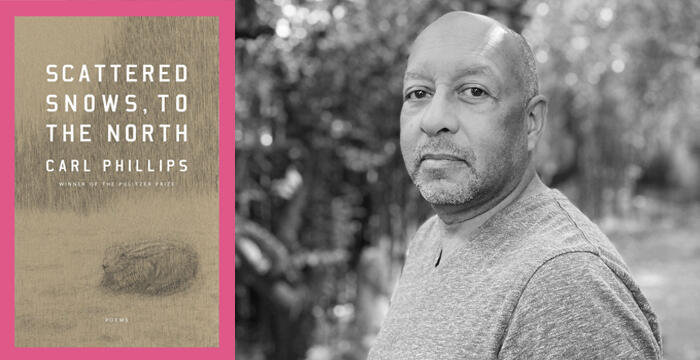

Carl Phillips : Scattered Snows, to the North

Today’s guest is one of the most singular and celebrated Anglophone poets writing today, Carl Phillips. We center his latest collection, Scattered Snows, to the North, his first since winning the 2023 Pulitzer prize in poetry. But we also use his three craft books written over the decades (in 2004, 2014 and 2023 respectively) to look at his body of work across time. We spend time attending to language, to syntax, to form. And equally, we look outward toward questions of voice, community, identity and more.

For the bonus audio, Carl contributes a reading of a medley of poems about black swans, poems by James Merrill, Randall Jarrell and Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon, which he comments on as he goes. He ends this remarkable reading with a black swan poem of his own. You can find out how to subscribe to the bonus audio and about all the other potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter at the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the Bookshop for today’s conversation.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode of Between the Covers is brought to you by All Lit Up, Canada's independent online bookstore and literary space for readers of emerging, quirky, and acclaimed indie books. All Lit Up is your Canadian connection for award-winning fiction and poetry, author interviews, book roundups, recommendations, and more. The only online retailer dedicated to Canadian literature, All Lit Up features books from 60 literary publishers and now they offer e-books in accessible formats through their ebooks for Everyone collection. All Lit Up makes it easy to discover and buy exciting contemporary Canadian literature all in one place. Check out All Lit Up at www.alllitup.ca. US readers can also shop All Lit Up close to home, save on shipping when they purchase books from its Bookshop.org affiliate shop. Browse selected titles at bookshop.org/shop/alllitup. Today's episode is also brought to you by Lena Valencia's debut short story collection Mystery Lights of which Julie Buntin says, “Brilliant and beguiling. These are stories with teeth.” From a lost sister transformed by cave-dwelling creatures to an influencer attempts to derail a viral TV marketing campaign with her violent cult following. Mystery Lights presents an exciting new voice in contemporary fiction. In stories that Clare Beams calls, “Sharp and finally honed as knives,” Valencia's characters speak to the fundamental truths that shape us and prompt readers to question their own assumptions about what it means to live and survive in this world. Mystery Lights is out August 6th from Tin House and available for pre-order now. Some of my favorite conversations, ones that I can only do a couple of times a year because of what they require, are with great poets who've been writing for decades where we can look together across their work over time. Today is one of those conversations where we center Carl Phillips' latest poetry collection, his 17th, but use his three remarkable craft books over the decades as a way to look at his most recent poems. It's a conversation that goes deeply into both the micro and the macro where at certain points, we're attending to language, syntax, and form, and others where we're looking at poetry in relation to the world at large; questions of identity, voice, community, and more. For the bonus audio archive, Carl contributes a remarkable gift for us. He created a medley of poems that he reads, all poems about black swans, poems by James Merrill, Randall Jarrell, and Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon, respectively. He discusses each of these as he goes, then finishes with a black swan poem of his own. This reminds me most closely of Jorie Graham's contribution of a medley of poems about rain and her commentary about them, and also Alice Oswald's reading from the Book of Job and a short ballad for Anne Carson. Lastly, since Garth Greenwell features prominently in today's conversation, I'd also mention Garth's reading of a poem by Frank Bidart. The bonus audio is only one possible benefit of joining the Between the Covers Community as a listener-supporter. Every supporter gets the resource email with every conversation of what I discovered while preparing, what we reference while we're talking, and where to go once you're done listening. Every listener-supporter can join our collective brainstorm of who to invite in the future. Then there are simply a ton of other things to choose from, whether rare collectibles from Rae Armantrout and Karen Joy Fowler to the Tin House Early Reader subscription, receiving 12 books over the course of a year months before they're available to the general public. You can find out about all of this and more at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now, for today's conversation with none other than Carl Phillips.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest, poet, and writer Carl Phillips has a BA from Harvard where he studied Latin and Greek Masters of Arts in Teaching from the University of Massachusetts, and an MA in Creative Writing from Boston University. He was a high school Latin teacher for many years and later for several decades until this year, he was professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis where he's just become Professor Emeritus. Phillips is the translator of Philoctetes by Sophocles and has written three books of prose, Coin of the Realm: Essays on the Life and Art of Poetry, The Art of Daring: Risk, Restlessness, Imagination, and most recently, My Trade Is Mystery: Seven Meditations from a Life in Writing, a finalist for the 2023 Pegasus Award in Poetry Criticism. Carl Phillips is best known, however, as one of the most celebrated and original poets writing in English today. Phillips is a four-time finalist for the National Book Award and Poetry, and was named winner of the 2023 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for Then the War: And Selected Poems of which Richie Hofmann said, “Carl Phillips is a poet of enchantment and persuasion. I couldn’t mistake these poems for any other poet’s work. In a moment obsessed with snappy performances, Phillips’ poems are contemplative, rich, and troubled. They are rarely axiomatic or quotable. Often, their power lies in their unfolding.” From 2011 to 2020, Phillips served as judge of the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize, the longest-running annual literary award in the United States, whose past judges include W .S. Merwin, James Merrill, Richard Hugo, W .H. Auden, and Louise Glück. He's a recipient of the Kingsley Tufts Award, the Jackson Poetry Prize, the Lambda Literary Award among many others. He's served as chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, has received fellowships from everyone from the Guggenheim Foundation to the Library of Congress, and has 17 books of poetry to his name, from his astonishing 1992 debut In the Blood, winner of the Samuel French Morse Poetry Prize to his 2020 collection Pale Colors in a Tall Field of which Lisa Russ Spaar said, “I read each of Carl Phillips’s books for the deepest pleasures poetry can provide — intelligence, linguistic chops, mystery. I also read them as primers, field guides, breviaries: as translations of personhood, in all our flawed and searching complexity.” Carl Phillips is here today to talk about his latest, 17th collection, his first since the Pulitzer Prize for his selected poems entitled Scattered Snows, to the North. Publishers Weekly in its starred review says, “Phillips has long been an exquisite navigator of the long sentence, and this capacity for meditation on the page is on full display, as is his flair for rendering thought through controlled syntax. Dancing between beauty and catastrophe, he evokes desire and longing in the face of forces that threaten routine and survival: ‘Isn’t every season,/ no matter what we call it, shadow season?’ These poems strike poignant and enduring notes, suffused in ‘the split fruit of late fall,’ which ‘wears best when worn quietly.’ This is another poised addition to Phillips’s dazzling body of work.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Carl Phillips.

Carl Phillips: Thank you for having me, David.

DN: I'm going to turn over the first question to another person. Not just any other person but a past guest on the show, one of my favorite conversations and most cherished poetry collections from 2022, Poet Ama Codjoe, author of Bluest Nude. A collection our current US Poet Laureate Ada Limón describes as follows, “Sensual, sound-driven, and brimming with a necessary truth, the poems in Bluest Nude are pulsating with both grief and beauty. Wrought out of resurrection and reclaiming, these brilliant poems honor the mystery and legacy of the body. Codjoe has written a true triumph of a debut that feels urgent and deeply human.” So here's a question for you from Ama.

Ama Codjoe: Hi, Carl. First, I will just say how grateful I am to have briefly studied with you at Cave Canem, which I think of as one of my truest schools. I remember really fondly how you would collage, quilt, and xerox these packets for us that were full of poets I'd never heard of and how years afterwards, I would stumble or encounter this poet and remember this moment of introduction, which feels like a generosity and somehow just a really tender offering for a young novice poet. Thank you. As an opening to my question, I wanted to ask if you would read the poem Surfers for us? Could you read it now?

CP: Yes. [laughter] It's so strange to do that. Yes, I can.

DN: No one's ever asked a question that's prompted a poetry reading as part of the question before like this. I love it.

CP: Oh, okay. Well, here we go.

[Carl Phillips reads from Scattered Snows, to the North]

Ama Codjoe: I love this poem and this new collection so much, and I can't wait to listen to you read it. Even though you're actually one of the poets who I've heard read enough that I can hear your voice in my mind as I'm reading your work, to me this feels like a particular and special kind of listening as love. The last time I saw you in person was in the green room before we read together, which was a really special evening. You and Shane McCrae were sitting together on a couch. Later, Shane would give you the most beautiful introduction and I said, “Here are two of the most prolific poets on one couch,” which for some reason tickled me to no end. I think one of the gifts of being alive while you're alive is trailing a little behind you and picking up the books that you publish every year or every other year. As a reader, I can sometimes perceive what seem like gradual and dramatic shifts in part because of the frequency of your publications. I definitely felt this shift when I read Then the War: And Selected Poems and I was so happy that it was honored with the Pulitzer Prize. I also feel like there's some kind of turn that's happening in Scattered Snows, to the North as well. I wonder how you think about these shifts and turns, or using the language of surfers, how you might, in this moment today, describe the second, third, or fourth lives of your bibliography. Or having heard this question, do you think about the various accumulations, culminations, experiments, departures in a completely different way? I understand the author may not be the most objective person to describe an arc, arrows, or whatever image or shape but I'm interested in how you might describe it. I'm so grateful to walk in the wake of your work. Thank you, Carl.

CP: Thank you, Ama, for that question and for your generous and kind words. I remember that evening well when we read together. It was such a lovely night. I guess like many poets maybe, I think of all of my work, all of my books as just one long extended meditation coming from a single life and often it seems to me, as in actual life, not writing life, we don't see unless until after a lot of time has passed, we don't understand that we were going through a phase or we were coming up to a major turn in how we conducted our lives, who we spent our lives with. It feels in hindsight sometimes as if we can see a narrative and everything was moving inevitably towards where we are now. But that's not how it actually is. It's all very random. Because I write very intuitively, I'm not able to write a book with a sense of a book in mind. I don't have a project or anything, so because of that, I'm just writing poem by poem. I know I've said somewhere before, it sounds a little melodramatic but I feel like I'm sometimes writing from a life but mostly writing for my life. I've never written for any reason then. It seems to be able to stay here I suppose. It feels like each poem is a small little rescuing device, which makes it sound as if I'm constantly on the brink of demise. But maybe that's how it feels, I don't know, maybe I am. It feels anyway as if that's the reason for writing. I'm not thinking, “Oh, it's time to address this change in my life,” or anything like that. I feel like I may have wandered away from the question. But I think the changes I've seen in the last couple of books suggest to me they seem as if they just come out of being older. I see how I write about relationships now, I see how I write about the body now and it's different but that makes sense because I'm writing about it from the point of being a 64-year-old as opposed to when I was writing at 34. I don't like to think any of it is less. It's just different. I feel as if I differently and maybe more confidently inhabit my body now than I did in my 30s. But what I write about changes slightly. It depends. Sometimes I think all I do is write the same thing over and over but through this constantly changing lens of getting older. Love is a typical one. I, of course, very much believe in love and I'm fortunate to have it in my daily life. But it's not how I imagined love would be when I was 25. It's better in some ways but also, it comes with all of the experiences I've had in the past that I have to carry with me. It's as if we never shed the past. We move outside of it but we're still carrying it. Like in a little sack is how I sometimes imagine it. This way, I think I'm carrying my various selves, so I'm still the 10-year-old me in some way. I don't know, I can be looking at a dog playing in the field and suddenly remember playing with a dog when I was 10 in a field like this. It's confusing and exciting. That's my rambling approach to that answer.

DN: [Laughs] Well, let me follow up or extend Ama's question because I really like how the way she's placing herself in a generational lineage with you and characterizing herself as trailing in your wake mimics the gesture in Surfers, the poem that she chose to foreground. Staying with this gesture, I wanted to read something that you wrote in your craft book The Art of Daring, a book that I really love from 2014. “The deeper one gets into what eventually amounts to a career, the harder it becomes to incorporate daring and risk into it. As in life, if we're lucky, we grow more comfortable, successful, and accordingly more aware that there's more to lose. So there's a resistance to changing what's in place already. Meanwhile, we're aware also of there being daily less time left, which can bring fear. This issue of time, it seems to me, should spur us on to live even more adventurously if not now, then when?—but mostly it doesn't, or so it seems when I look around me. Why risk what it's taken us all our lives to at last get hold of? Or if we haven't gotten it by now, why try? Why bother? Yet for the artist I think an appetite for a certain recklessness is crucial, if the work is to not only extend itself, but also deepen and meaningfully complicate itself.” I read this as an extension of Ama's question, thinking about how you are at a major inflection point in your life, having finished several decades of teaching, moving to Cape Cod, returning to where you lived during some of your teen years and where your father lives now. I wonder how this dynamic of looking back at what you are departing from while moving forward into a new phase in your life that is also in a way a return of sorts, how it relates for you around the ways risk becomes harder as one's life and career takes on a greater and greater shape. Because particularly right now, in a way, you're breaking form in your own life in terms of you're entering a new life or a new phase of life. I wondered if maybe you could think about how that does or doesn't echo in the book we're talking about today.

CP: I feel like I should have been warned that the questions would all be hard. [laughter] Well, I like that idea of breaking form, I mean I've only been retired a month so a lot of things have happened very quickly. It's a lot to have moved from St. Louis, to have sold a house, and sorted out tedious things like Medicare. That's a whole different thicket of complications and yeah, start anew. But it's interesting because you're right, I'm starting in a place that I have lived for a long time before. One of the things that makes it new on one hand is I have moved here with my partner of almost 11 years who is not from here, is born and raised in the Midwest. In a way, he's discovering this place that I know and I find I'm discovering it in a new way, seen it in a new way through his eyes. At the same time, what's been important for me to stay aware of is I had a long relationship with somebody else in this very same place and not in this house but 15 minutes from here. It's weird to go, say to a restaurant for the first time with my partner now but this is a place that I used to hang out with somebody many years ago. Things like that. It's a return and it's also a new experience because I've not been there with him before. Well, I guess that's the personal life side of it. But with writing, I don't know, I mean, it's not that I disavow what I said in that essay but if there's one place where risk continues to always happen for me, it's on the page because maybe it's the one place where there isn't anything to lose, it seems to me. I know people could say they don't want to lose their career or their reputation, they don't want someone to hate the newest book or something. But I guess I don't think anyone will believe me. I have never written for accolades ever. It never occurred to me that I could be a poet in the world. My mother wrote poems when I was growing up for a hobby. I wrote them for a hobby. I thought I was going to be a high school Latin teacher my entire working life. I was looking forward to that and enjoying it while it was happening, so it all has been a fluke. I've seen plenty of articles that suggest that I've somehow had a plan and plotted to be whatever I am now, and it was all about connections that apparently I stalked out. No, it's all been pretty random because I actually am a lot more naive than I think people think when it comes to real life. So in that sense, I've always just done what I wanted to in poems. It's hard for me to answer questions sometimes when people say, “Well, why do you do this? What does this mean?” because I truly think, “Well, I don't know how else would anyone do it?” I read other people's books and I see how other people do it. But I think well, as with walking, we each have our own gate and we all do it the way we do it. There's no explanation for it. It still is mystifying to me. It's gratifying to me that people read the poems and seem to like them. But there's a part of me sometimes that thinks, “Well, that's so strange that people would like them because they're just my weird little ramblings about being me.” But I am a human being and I can see how that can be one touchstone for understanding what it is to be a human being.

DN: Well, in the same book, in The Art of Daring, you say that increasingly for you, daring has come to mean restraint. But if I were to have to answer Ama's question on your behalf, my answer would be more in line with something you've said more recently. You said, “Daring has come to me in restraint 10 years ago,” and five years ago when talking to Rick Barot when he interviewed you for The Paris Review, you said, “My newest poems are very invested in storytelling as a kind of unraveling. Poems that proceed by and often end in loose ends rather than anything even vaguely like resolution. Unraveling seems maybe more true to how our lives are. We like to think they're compartmentalized and neat but it seems to me that life is actually about a lot of spillage that we're trying to hide from ourselves and from other people.” One idea of yours that's often quoted and that you often bring up is it's a human need to give shapelessness a form. But it feels a little like the new collection is in some ways the rehearsal of the opposite of this as it is very death-haunted with recurring motifs of autumn, twilight, snow, winter, extinction. When I think of unraveling in shapelessness rather than form, I think of how the book opens with “as I took off my clothes” and ends with, “they took off their shoes, their clothes, and swam out to the dark ship.” In your most recent craft book, My Trade Is Mystery, you recount a childhood dream where you are separated from your mom at the North Pole and there's snow everywhere. The snow is absorbing the sound of you calling for her, the snow obliterating any ability for you to see or orient yourself and I wonder if one way to look at your new collection Scattered Snows, to the North is a collection that is not only making shapelessness into form but also finding forms that confront one's ultimate shapelessness. Talk to us about whether daring still feels increasingly about restraint as you said in 2014 and how if at all we are unraveling your new collection.

CP: When I say that daring is more about restraint and I think this is reflected in this new book, I feel as if for a long time in many of my books, I would sort of end with some kind of epiphany that might seem to come out of the blue but would turn out to have been something that the poem was leading up to the whole time. At some point, I just got bored with that. I guess I'm very interested in how poems end. I've always been resistant to closure because epiphany doesn't have to be closure necessarily. But often it seems to me that large things in life, doors don't close that loudly in reality. To me, it's daring to end a poem sooner, to end on what would seem like a non-ending moment, that to me is restraint. It's restraining myself from an impulse to wrap things up or decide how people should think about what was just said. I mean, even in the opening poem of this new book, it's very short. In some ways, I feel as if nothing happens. Two people are undressing, there's a remark about the weather outside, then there's this sentence that says it's difficult to believe in them, the beautiful colors of extinction but these are the colors. The first question could be, “What colors? What are the colors? What are they talking about?” [laughter] But I knew when I wrote that poem, I feel as if I've said everything that needs to be said if one wants to spend enough time with these three little sentences, that may not be the case for everyone but to me, it took a lot of restraint. I took staring at this for weeks to believe that it was a real poem, especially because I also am, as people know, very fond of a long periodic sentence. In general, that poem is just very straightforward sentences, very spare syntax. Meanwhile, there is unraveling. I agree. I see that in these poems, the unraveling that can be mortality I suppose and the unraveling of memory. But I'm not sure that that means that there's shapelessness anymore. I'm starting to think that there's a shape to the act of being unraveled, to unraveling another thing. It just means a shape has been taken away if we want to unravel a sweater, so we have a ball of yarn at the end but that we still have a shape and we still have some substance but it's no longer what it had been shaped into. So maybe I'm curious about that. Even the idea of snow, on one hand, disguises the original shapes of objects but it provides a new shapescape if we can make up that word. We might not see anymore that cars and bushes are covered but there is a weird white shape that's been made, so it's both obliteration and creation.

DN: I love that. Could we hear the first two opening poems in the collection?

CP: Sure. This first poem is called Regime.

[Carl Phillips reads from Scattered Snows, to the North]

There's the first poem. Second poem's a little longer. It's called Before All of This.

[Carl Phillips reads from Scattered Snows, to the North]

DN: We've been listening to Carl Phillips read from Scattered Snows, to the North. I have a question for you about these poems but before I ask it, here's a question for you that refers to the opening poem. This question is from the poet Richie Hofmann, whose most recent collection A Hundred Lovers was described by Eduardo C. Corral as follows, “Richie Hofmann chisels the excess away, brings to light splendid language. His formal intelligence is ravishing, restless. Crackling with vows and disavowals, studded with keen and elegant imagery, simultaneously raw and curated, his poems remind us the flesh is as curious as the mind.” Here's a question for you from Richie.

Richie Hofmann: Hi, Carl, it's me, Richie Hofmann and I have a craft question. You've spoken about the tension and erotics of syntax, and about the push and pull of lineation. Reading your new book with its dramatic opening poem almost in haiku stanzas, I'm curious to know more about your thinking about the stanza, the little room that groupings of lines make, and also the lines that drop into almost stanzas, how they break and shape, cut against or reinforce. Are they architecture, music, or both, or neither? Thank you.

CP: Thank you, Richie. It's so strange to hear these voices of people I know. [laughter] Strange and comforting. Huh. Well, I'm just looking at that first poem Regime with the little short lines. Is it music or architecture or both, I mean I've always thought of lineation and stanza breaking, and making as a kind of musical notation. For me, because I believe in lingering slightly at the end of each line, I feel as if I'm trying to deliberately measure out rhythm and the pace of things. It upsets me when someone reads one of my poems or their own poems as if there are no line breaks at all. Kind of reading you go to and you think, “Are they reading prose poems? They seem to be reading prose,” so there's partly an answer I suppose. I guess in this poem, for example, in Regime, I know people can't see it but it is three sentences that are cast across five stanzas. The first four stanzas are three lines, so that's 12. The last stanza is two lines, so that's 14. I guess I did have the sonnet in mind because I think of a sonnet though, not as 14 lines, but as a way of arguing or thinking. There should be certain turns at certain places, it seems to me. I like to think this poem has that and a feeling of kind of conclusion, and non-conclusion at the same time in that final couplet. What else is it to say about it? I guess one thing to say is that it's only at the very end that there's a closed line that ends with punctuation. From the very start, I've been interested in having stanzas not be closed. To me, it generates momentum down the page because you can't stop in the stanza. You're forced by the grammar and syntax to keep moving. I've always been interested in a three-line stanza because there's a built-in instability to it. I think that might answer some of the questions. The drop line thing, that doesn't happen in that first poem but I know what Richie's talking about where suddenly, a line appears beneath where it would appear if it were on the same line as the one above. It's always hard for me to explain this to my publisher. They think it's just a typical indented line but actually, it's meant to be a sort of continuation. It's a way of having almost a stanza break effect but it's not a full stanza break, so it's become like the difference between a whole note and a half note in music.

DN: Well, let me ask you a question from me about the opening poems too. I wanted to ask you about description and your relationship to it, which you've already alluded to about this opening poem. In The Art of Daring, you talk about storm watching with your partner at the time, a landscape photographer, and how his instinct was to first see the world for what it is rather than what it conjures in his mind, which comes later for him and that you are the opposite, first seeing what something resembles, then only reluctantly what it is. One thing I noticed, which you've pointed out already today in these poems, is an attentiveness that is also abstracted from physical detail. Like the lines, “It's hard. to believe in them, the beautiful colors of extinction; but these are the colors.” Or in the poem Little Winter, “Little fever-snow of days when, just as certain colors, even now, can suggest a time that you called innocent, more honest.” In both cases, as you've already alluded to, you reference colors without specifying them. It made me wonder if you could talk more about description, specificity, and abstraction in this regard, whether this is something emblematic of your approach or whether it's a departure from it.

CP: It's hard to know if it's emblematic or departure but maybe I'll get there as I answer this question or try. It's interesting because on one hand, what's crucial to me is to very accurately describe the physical world. I feel as if poems to me are not transcriptions exactly of the world but I feel as if we do have to recognize the world of the poem. As I used to say to my students, a large part of making a poem is world-building. You want your reader in the context of the poem to believe that what is happening could happen. So if you're going to describe trees in winter, you should be describing them as they actually appear, depending on what part of the world you're in. I know sometimes my students find it a little tedious for me to care about those details but it matters. What kind of a lawn are we walking across? Or if someone's saying, “The lawn felt good on my feet.” How did it feel? Why did it feel good? It matters to be specific, I think. Although many people think that my poems are allegorical, they're not intended as allegories. I was asked once in an interview, “There's a fox in one of your poems. What is that about? What is that standing for?” I felt bad telling them it's the fox that comes into my backyard every night. [laughter] There's a fox running in the backyard and that's all it is. It doesn't stand for anything. On one hand, that specificity is important but I also think it's human for us to impose meaning on things the way other animals wouldn't. We are conditioned to think of, I don't know, like a crow as being full of mischief or being a thief and stealing things or something. Or if it's black, we're supposed to associate that with death or something but it's just a crow doing whatever crows do. I feel as if in my poems, increasingly, but I think I've always done this, I often will correct myself. I'll find myself starting to think about even in that poem, that longer poem I read this morning where I talk about the trees bending seems as if they remind me of this but then there's this moment of, “Well, but that's not what they're about. They're just trees bending in a wind,” but it's as old as at least Homer in The Iliad, there's some scene where an embattled hero is described as an oak tree withstanding these winds and all of that, so we're always trying to match up human experience and impose it on the natural world. I think maybe because it's lonely to be human and we want to believe that these things actually are speaking to us or have us in mind the same way people want to. They lose somebody, a dog or a human and suddenly, they think that a bird flying and landing on their hand is the dead coming back to send a message. That would be nice to believe but I myself don't believe that. I think it's just random. You die and that's it but that's a harder thing to sit with.

DN: Well, we have another question for you that like Ama’s is about time but like Richie’s is more on the level of language. This question is from the poet Han VanderHart, author of What Pecan Light and the upcoming collection Larks. They are also the host of the Of Poetry Podcast and co-founder and co-editor of the poetry press River River Books, so here's a question for you from Han.

Han VanderHart: Hi, Carl, this is Han VanderHart and I'm calling in from sunny North Carolina. As a reader who is a longtime admirer of your formal engagement with several classical influences, I think of the Homeric simile, John Milton's blank verse and I'll include Geoffrey Hill's sculpted au revoir here. I want to ask a question that relates to your new collection Scattered Snows, to the North, or really any of your collections a reader might be spending time with now. My question is about how, in your poetry, you build your preferred verb, lyric arguments whose grammatical for stalling and extension resonate for me with a queer experience of lived time. For example, the delayed subject, the subordinate clauses, the volta disjunction. Do you see yourself as working against received logical forms or having a queer sensibility of time in your syntax? I think this is a question about how arguments can be queer and how songs can be a queer argument. But ultimately, I want to ask you what you see your particular grammar as really risking in your poems.

CP: Thank you, Han, for that question. It's a good one. I now see my sentences, syntax, and all of that as being queer but I didn't at the start, not least of the reason for that is because I didn't know I was queer. I didn't quite understand I was queer. I was just writing poems and had to write my way into that understanding. But I have, over the decades, come to realize that well, first of all, I should say when I first started writing in a serious way and trying to send poems out, I was very aware, I would look at all these journals and try to find out journals that might be suitable for my work and I kept coming across them, and thinking, “Well, I don't feel like I write any poems like this.” I was disappointed because my first reaction was, “That's because I'm not a poet. I seem to not have the trick of how to write a poem.” It took me a long time to realize, “You might be writing something that no one's writing, Carl. That's all.” That's all that means and, “You're maybe not original but you’re yourself, you’re unique.” But it took me a while to see that those very things that you mention, the delayed resolution of sentences, the constant stepping back, the syntactical evasions, to me that is part of what it is to be queer, especially if someone in my generation, happily, there's a lot more openness about queerness these days though it's still dangerous for many people in many parts of the world to be openly queer. But certainly, I grew up not even knowing that was an option. When I learned that queerness was an option, I was also very clear that it was the wrong option in most people's minds and that there was something subversive, and terrible about being a gay person. I think we realize this even as kids. We learn to mask who we are and we also learn the codes for how to recognize others who are like us. I sometimes think of my sentences as ways of publicly speaking, saying one thing. But those who understand see that, “Oh, this is a queer person,” they can see that simply by the sentences. This is a navigation system that refuses to have anyone be able to pin me down in some ways. It's not exactly like being self-closited or something. It's just protection, I suppose. But the fact that I keep doing it, I guess because I don't know any other way to write, I think that part, I think of it as a revolutionary act in some ways, I mean, just as I think to be openly queer is a revolutionary act just by existing, I think refusing to write in what is considered the proper way is resistance. I remember when I was in a writing program, one of my teachers told me that I was going to have to sort out how to be less Mandarin. That was the term. I went home and looked it up because I didn't know what it meant. I thought a Mandarin was an orange or something in China. [laughter] But then I learned it was these baroque, overly elaborate sentences for no particular reason. At the time, I thought, “Well, maybe that is a problem. Maybe my sentences are posed.” But then I realized I couldn't write any other way. I started writing when I first started reading William Carlos Williams and I was amazed at how simple the sentences were. But it never occurred to me that I could write those. I still find him one of the poets I admire the most but I can't write that way. This kind of linearity that I sometimes associate with a public notion of masculinity and of what is considered clear argument, even my essays, I've been told that I seem to never really get to the point. But to me, an essay is about associative leaping from idea to idea. What I trust and what my risk is in writing an essay is that the reader is going to slowly take these pieces, and start to collage them together and see that, “Oh, it seemed as if he was hopping around in random directions. He always was dancing around this subject. These were just different entry points.” But I kind of go in, then leave without tying each piece up. I think of the poems that way too, so yes, I guess it is queer but I wasn't conscious of that at the time. Of course, there are many queer writers and everyone writes differently, so it's not as if that is the queer way to write a sentence by any means.

DN: Well, I really love Han’s characterization of your work as building lyric arguments through grammatical forestalling and extension. I think it rhymes with what others have said about your work, including Richie mentioning in his question the push and pull of your syntax and also Garth Greenwell in his incredible essay on you called Cruising Devotion where he says, “The crux of Phillips's poems is this: A life of pure abandon, a life of pure restraint; they are irreconcilable, and neither is bearable in itself. It's to attempt to think through or around or past this irresolvable conundrum that Phillips mobilizes the rhetorical strategies of the via negativa, making what could be sterile impasse, the barren end of thought, instead into something productive of new revelation.” Or Rick Barot in The Paris Review saying, “Phillips has always maintained the perhaps paradoxical quality of being candid and private at the same time.” Or Dan Chiasson in The New Yorker characterizing you as, “A poet of erotic life as scored for solo contemplation.” Or in your own words when you were on the VS Podcast back when Danez and Franny were hosts and they do their rapid fire questions toward the end, and one of them is the best thing to hear during sex and you say, “Stop, don't stop.” [laughter] All of this feels like a crucial element of your work, both on the micro and the macro level. But before we bring it back out to how it manifests in its broadest strokes, I wanted to stay a little longer closer to language and syntax. The grammatical foreselling aspect makes me think a little of Rosmarie Waldrop's thoughts on prose poetry where what she calls gap gardening is a means of obstructing the passage of time from within the sentence to interrupt the experience of time passing that is inherent to sentence structure. In your essay, a brief stop on the trail of the prose poem in your first craft book Coin of the Realm, you start with The Annals of Tacitus, a first-century Roman historian and you suggest that because the first line is written in dactylic hexameter, like an epic would be, that this choice signals that what we will read is more than history. Then later you meditate on one of Russell Edson's many weird poems. You're only the second person who's brought up Russell Edson in 14 years. The other being Lydia Davis. You meditate on his poem On the Writing of a Prose Poem and that poem goes as follows, “When thinking of writing a prose poem it seems more than natural to think of suicide; to think of someone at last exposed to the God of things who might thunder, as I imagine it, from the sky, you have ruined my thing, now I shall ruin your thing,” and you say, “Hear Edson suggesting, as I interpreted, that the prose poem is the result of pitching ruin against ruin, offers a direction of thinking about the prose poem that might be the most reasonable one available. If we can think of mortality as an ongoing form of erosion, and I do, and of erosion as a form of ruin, not without its possibilities for beauty along the way, then perhaps the prose poem is simply another proof of what art does best and for me was meant to do in the making of poetry, we have captured one thing and in so doing, we have briefly mercifully staved off another.” It is almost I think like this is a fractal aspect to your poetry in so far as your collection is dealing with this question in your life and also in life more broadly but also finds itself doing this at the level of the line, and the sentence, perhaps gardening in the gap, to borrow Waldrop's phrase. I wondered if this sparked any further thoughts for you about grammatical forestalling or as you titled a recent talk, Pressure Against Emptiness.

CP: It's interesting, that gap gardening idea from Rosmarie Waldrop because I hadn't thought about that. But the idea of a sentence says the progression of time, which obviously it is, but there are ways in which you can stall arrival in that sense, then each sentence becomes a kind of exercise in mortality versus immortality or something, or refusal to want to accept that the sentence must end, which I suppose is also involved in that idea that I first got from Lyn Hejinian of a resistance to closure itself. This idea that the poem does have to end but that equals a little death in some ways, so how can we make it not, which leads to people ending with an ellipses, dash, or nothing or the restraint I've talked about where you refuse to have a tying up of the argument. So I guess I agree that it seems to be at work, though I hadn't really thought of that at all. I feel as if that's not a very adequate answer. [laughter]

DN: I like that you're discovering it like this in real-time.

CP: Well, I am. One of my fears about being on this show is that it's long enough to lay bare how Carl isn't even all that clear of what he's doing himself. [laughter] Yeah, I'm not very conscious of that. But also this idea of gap gardening ties in with what I said earlier in the program about the poem being a kind of staving off of something. I've described it somewhere before that I think of each poem as a wedge between myself and what feels at the time like the unbearable. Then you've got this wedge and you feel as if, “Okay, I've been saved again.” But then somehow, the wedge isn't enough to hold up so you have to make another one and reinforce it with, in this case, another poem. I wonder if maybe just the making of literature is always a kind of large or a kind of staving off of the mortality that we know is there waiting for us. Because as long as we can say something, we're alive. As long as we can keep making, we're physically in the world ourselves.

DN: Could we hear one of the prosier poems in the book? I was thinking maybe Searchlights or if you have another you'd prefer.

CP: Well, I was going to say I'm very good at doing what I'm told. I'm actually not but in situations like this, I am. [laughter]

DN: All right.

CP: I'm just going to read the poem you mentioned.

[Carl Phillips reads from Scattered Snows, to the North]

DN: We've been listening to Carl Phillips read from his latest collection Scattered Snows, to the North. So instead of asking you what makes prose prose poetry, I wanted to ask you a harder question but one that I'm confident you're up for. I think it was in your recent Pressure Against Emptiness talk but I'm not 100% sure. But in one speech, you said sort of as an aside that you tell your students that 90% of poems out there aren't poems, which of course begs a giant question. Tell us what makes a poem a poem, obviously for you, and what one of those 90% of the poem-shaped pieces of writing that are often called poems and read as poems, what those poems or not poems are lacking when you encounter them that makes them something else.

CP: Okay. [laughter] I realize how arrogant I must sound to have made a big statement like that in about 90% of poems but I'm going to stand by it. First of all, part of it has nothing to do with form at all. Well, it's easier to talk about form, so I'll do that first. I know it's somewhat cliche to complain about this but I guess I think that a lot of what was called poetry to me seems like prose and lines. What makes me think that is I'll look at a line, I'll look at a poem line by line and see no reason why this line had to be broken where it was or what benefit there is to my seeing just this chunk of language in isolation. To me, lineating is a way of measuring information. You're giving in portions and saying, “I want you to look at this set of words right now, then this set, then this set in this order.” But when I look at many poems, I feel as if, “Oh, okay, I don't really see why is this one word taking up a whole line,” or “Why are these 20 words taking up a whole line?” Then I start to distrust the authority of the poet because I think, “Well, they don't know how to make a poem architecturally. So I'm not sure I can sign on in terms of its form.” Okay, that's one thing. It continues along with stanza breaks if that just seems random. I've complained for many years that the default stanza is the couplet. People think, “Well, he hates couplets.” I just hate couplets that are not meant to be couplets. So for me, the hardest thing when I make my own poems is coming up with the final shape because it's not right until it's in the right shape. It has to feel inevitable by the end, even though I've usually spent hours really getting it right. But that's me. It's probably for the best that I retired because I have seen the eye roles that I get when I make these statements. [laughter] That's okay. I think the reason people resist what I'm saying in this manner is because it means that they would have to work harder. It means that they have to hold themselves accountable to a knowledge of form, which doesn't have to mean any traditional canon. It can mean whatever you do, what is the reason why you did it this way. But one of the things that mostly troubled my students was when I would simply say, “Just talk to me about why the poem looks the way it does on the page.” They would have no answer. Or they say, “Well, I don't know. It came out that way,” or “I don't know.” I think there should be an answer, even though we might not immediately have it when we've just written the poem. But another maybe larger part of my dissatisfaction, I suppose, is when poems seem merely a transcription of what I already know to be the world. At which point I think, “Well why was this poem written?” For example, if someone wants to say, “I went into the meadow. I saw a bee landing on a flower. I felt good,” and that's the end of their poem. To me I haven't seen anything I haven't seen before but I would love to be shown it in a new way because what I also used to tell my students is our experiences are fairly finite. Most poems aren't about anything new. They're love, death, whatever, usual big themes, fear. But why do we go to certain poems and say, “Oh, this has shown me yet another way to look at the idea of fear”? Or why do we revisit the same poem over and over across centuries? It's because it touches in some way that is not how we have understood it before and we want to return to it. So I think that's the challenge of how to transform daily experience into something new but at the same time, in such a way that the reader says, “I've never seen it this way and I'm persuaded that this is a valid way to see it,” then you add it to your bank of experiences. I used to think once I'd written my first book and come out, and I thought, “Well, I guess I've solved the riddle of being queer.” That was the answer. I'm gay. But what about right now? Little realizing that well, that's going to change over time. It's like saying, “Well, I've solved the subject of love.” [laughter] “No, you haven't.” You see it clearly right now at 22, and 42, it's going to look very different. I think it's just that. I think we all want to write in large part because we have some thoughts and feelings. We want to put them on paper. But the first question I asked myself after I've written a draft is what would make anyone think they should read this? Because I get rid of a lot of things of my own, simply by realizing nothing here is new or it's not new within my body of work. I've said this way before, so that was a nice exercise but it's not a poem. But maybe that's a little harsh. I do believe in generosity and I believe that there's room for all of it. I'm not the person to determine what is a poem and what isn't. But let's just say what I want from a poem when I'm reading one by someone else is I want to learn something about the world and I want to learn something about language. So I want to be excited that, “Oh, I've never seen a sentence made that way,” or “I've never seen someone interrupt themselves in this strange way that at first seems almost like a mistake, but it's working here, how come?” That's the kind of poetry that excites me. But that's just one. That's not the answer. [laughter]

DN: Well, we have a question for you that is also I think about your philosophy or towards poems and poetry. This question is from the poet Nicole Sealey, the originator of the now huge poetry phenomenon every August, The Sealey Challenge. Her most recent book, The Ferguson Report: An Erasure, won the 2024 OCM Bocas Prize in Caribbean Literature in the poetry category. So here's a question for you from Nicole.

Nicole Sealey: In your poem Fist and Palm from your latest, which I'm currently enjoying, you write, “These songs I've built from things too difficult to speak of.” This reminds me that poems owe nothing to truth. My question for you then is what, if anything, do poems owe?

CP: What do they owe? Oh, huh. My understanding of the question is what do they owe us in terms of accuracy to the truth. I do like how that overlaps with what I was just saying because on one hand, I think a poem does have to show us the world as it is, I mean the real world, even though the way it's presented in the poem might not seem recognizable right away but it has to be authentic. But in terms of what it owes us in terms of personal truth, I mean in the way this gets into the idea of confessional poetry, I suppose and I like that part that Nicole quoted about words that are about things too difficult to speak of because you could say, “Well, haven't you spoken of them if you've written words?” But I've always thought that my poems are speaking about one thing that only I know about but they also are speaking about something that is available on the page. So I guess I think of poetry as very private. One of the difficulties I got into early on in my first couple of books is that I think people were a little scared of me because they assumed that everything in the poems was something I actually had done. One of the exciting things to me about a poem is it's a place to do a lot of things that you might not do in real life but you can have the fantasy. Yet, I also think every poem is autobiographical at some level. Just the words we chose, the order in which we chose to put them says something about who we are as individuals. But for me, it's almost as if there are things too difficult to speak of but they need to be addressed. To me, a poem comes out of the need to at least maybe indicate the emotional, psychological narrative, which is not the same as the narrative story of what has happened. I think it's why I've read somewhere that some people have said that my poems feel like overheard bits of conversation and you don't get to see the context. I don't purposely do that but I see now that that's a fairly accurate description. The context is removed sometimes because that's the painful part. The part that actually the poems sprang from is too difficult to speak of. But here's how it felt, here's how it felt psychologically to come through that. But no one's going to get the actual autobiographical story in that sense, which can be frustrating for some readers if that's what they want. But that's not the poet I am but there are plenty of poets who are.

DN: Well, to extend what Han called a queer experience of lived time via the delayed subject, the subordinate clauses, the volta, the disjunction, and taking this out of questions of syntax and of the line into larger meanings and themes within your work, I wanted to start with the question that you posed to Gabrielle Bates when she was on the show. Here's you asking the question to Gabby when Gabby was on for Judas Goat.

CP: Hi, Gabby. It's Carl Phillips. Congratulations on Judas Goat. I have a question for you. What if I said that your poem When Her Second Horn, the Only Horn She Has Left, which I can't stop rereading, what if I said it feels simultaneously like an ars poetica and a crime of passion? What if?

DN: So here's the poem by Gabby that you foregrounded.

When her second Horn, the only Horn she has left, goes up through the white and copper topped tunnel of my eye and enters the basket of bone. We are no chimera, the ancients ever dreamed at once, too mundane and two fearsome at once to separate and too dependent. There is more to say, but my speaking is done with me. The goat screams. I vibrate, My screaming is done. The first Horn. I hold in my hand like a dagger clasped by the blade. Black blooded at the base whisper of for lacing the ripped edge. I'd only wanted her to stop lying.

I wanted to use this, your choice of this poem, and the piercing of the eye and its basket of bone by the goat horn to talk about penetration in a variety of ways. When asked in a conversation for Boston University, “What is a uniquely Carl Phillips poem?” what you describe is the interpenetration of different modes within one sentence. You say, “A poem by me is going to use language in unpredictable ways. It’s going to be a mix of long, syntactically complex sentences, and then ordinary statements that anyone might say on the street. I feel like my poems are physical. There’s a sense of having come through something because of sentence manipulation. I want each sentence to be a physical experience in some way.” You could also say that the way you've structured the book involves a sense of penetration across boundaries. There are three different sections, which each suggest one to the next, a forward linear progression, one that we might expect from a narrative. Part one is called Somewhere It's Still Summer, part two, Rehearsal, and part three, When We Get There. But each section has a poem titled the same as one of the other section titles so that for example, the first section ends with a poem that shares the title of the third section When We Get There. Each section, in a sense, is penetrated by a poem that is nodding to a different section. But when talking about penetration in your work, we are most often talking about it sexually or sexually and metaphysically in concert. As you say in an earlier poem Topaz, “Our longing / now to fill a space, and now—getting filled—to be the space / itself.” You even have a chapter in one of your craft books entitled Penetration in the Art of Daring. In that book you say, “I think restlessness of imagination but also bodily, by which I have mostly meant sexual, I see that now, is what brings us to that space where art and life not only seem interchangeable for a moment they are so, space where they penetrate one another. Space in which caught between the two, we can be variously lost, broken, or we can summon that daring that can bring us — loss and brokenness, and toe to unknowing.” You also say, “Restlessness carries us to penetration – we pierce the world as we knew it. The world as we've never known pierces us, in turn, daring pushes us past this, and then what?” I love that you end this with an unanswered question and I think on first blush most people would get why you would liken penetration to both restlessness and daring. But even as I'd love to hear more about either of those, I also particularly love to hear about this notion of penetration as a method of unknowing when many might imagine that we penetrate something to know it instead of to unknow it.

CP: Wow, I seem to say a lot. [laughter] I was just thinking, “Wow, Carl, really? Do you say all these things?” It just means I'm old, I guess. I've had time to say a lot of things. I agree that on one hand, penetration is a way of owning, in a way, something. Sometimes, that's how people see it sexually, pinning something or someone down. But I guess I think that there's another way of thinking of penetration as you break through what is knowable, what you see in front of you. But you're not guaranteed what's on the other side. In that sense, there's the possibility for at least discovery. What we experience or discover may make us strangers to ourselves or we have to reconfigure who we thought we were. That's a form of unknowing, I suppose. But I think of penetration too as something that it's both ways, I mean penetration, you can be the penetrator, you can be the penetrated, so I think they're both different ways of knowing and unknowing simultaneously. I guess that's the way in which I see penetration as being a way to both know and discover, and be unknown or have one's assumed knowledge questioned. But also, I think penetration can be misleading, the idea that penetration is to own something and to know it, I think that's often what we think, and what we discover is that, at least with a human being, that you can't pin a person down in that way. You can pin them down physically if you want and you can be pinned down physically. That doesn't mean that we have any knowledge of who the person is inside as an emotional self and a psychological self. I think that's the problem sometimes it seems to me with sex in some ways. It's the problem that is in Louise Glück's poem Mock Orange where this idea that you would think at the moment of sexual union that now, we are one, we absolutely know each other, but that's the actual moment at which the two cells fall away from each other and we realize that there's a part of us that can never be penetrated, that can never be known. Even if we try to explain it to someone else, they can't know what it's like to be in our head, our body. There's something very misleading about penetration because I associate it sometimes with conquest. But what have we conquered, really? We've just conquered the physical self or been conquered physically. But we're still very much ourselves and that seems to remain intact.

DN: Well, returning to Garth Greenwell's essay, Cruising Devotion, he says at one point about your poem, Hymn, “After all these lines nothing is resolved, nothing is finally arrived at, arrival isn’t the point; the point is an articulation of restlessness, achieved through rhetorical and conceptual means that I think have a particular pedigree in the tradition of apophatic theology, the via negativa, the disciplined path not of knowledge but of ‘unknowing.’ The argument I want to make is that Carl Phillips has used sex as a mode of philosophical inquiry.” Then later, he says, “These branching inquiries have led Phillips to a remarkable exploration of the tension between competing desires or impulses that he has framed as a series of dichotomies, dichotomies that he interrogates to the point of dissolution: domesticity and wildness, indulgence and restraint, stability and restlessness, safety and risk, even risk so unbridled that he has called it, at times, ‘suicidal.’ In exploring these impulses, Phillips’s goal has not been to adjudicate between them, much less to reconcile them, but instead to make the tension between them, their irresolvability, itself a tool for further inquiry. This has produced a poetry of shimmering, ever mobile negotiation, the intellectual rigor of which is both remarkable and takes a particular form. Its closest analogue, as I’ve already suggested, is apophatic theology, the mode of religious thinking—of thinking about absolute experience—that characterizes what we often call mysticism.” At another point, he suggests your work makes a heroically defiant claim of sacredness made on behalf of demonized bodies. All these ring true for me as a reader, but I wondered if it rings true for you as a poet and how you see, if you do, sex and the divine or the spiritual in relationship to the body. I know from reading your prose that encountering the Greeks when you were young and discovering their twinning of sex and divinity, one example being Sappho's prayer infused with sexual desire, was impactful to you and that you also admire the work of the poet-priest George Herbert where in your lecture on Confession at Warren Wilson, one quality of his that you like is the unanswered question: Is he being blasphemous or devout, arrogant or humble? And you ask yourself, “If sin can lead us closer to God, could we consider it as recommendable, even good?” But your poetry in regards to its language and references or in what it notices seems quite secular, which doesn't, in my mind, contradict anything Garth suggests, but how do you see the divine, the mysticism of negation, the spiritual or the devout or the sacred, if you do, in relation to your poems, and more pointedly in relation to the way you portray sex in your poems?

CP: One thing I do want to say in front is I sometimes wonder if all my poems have been one long attempt to justify behavior. Long ago, I came up with some phrase, flexible morality. I thought, “Yes, that's what morality should be. It should be flexible. No one should say this is right, this is wrong. There's no binary about it.” But I grew up with that being what it was. There's good and evil. There's right and wrong. In coming into my queerness, of course, I came to see that, well, there are other options. Also, even before that, being biracial, I was constantly, as a kid, asked why am I not Black in the usual way or am I trying to be White or “What am I?” was a very common question. It was hard to figure out like, I'm just who I am. I don't feel I'm supposed to fit in any one place. Anyway, in terms of morality, I feel sometimes as if the poems have often been these slippery philosophical arguments trying to justify messy behavior. Even my reading of George Herbert in that talk, I mean, that's one way to read him. I don't think everyone does, but is it more convenient for me to think that, oh, to sin is actually maybe a way to come into some kind of understanding of goodness or what's correct? Or is that just my way of explaining it away? My relationship—to get to the actual question—to the divine, I'm not a religious person. I don't have any religious faith or anything. There's a part of me that at least wants to believe in the ancient Greek idea of Daimon, the idea that there are these forces, not gods like Zeus or somebody like that or Athena, but just forces that cause people to move into rage, to sorrow, or whatever. But I don't think that's true. I just think we're here and then we're not. But I've always been fascinated with the impulse to want to believe in something. I think it's because it's bleak to be totally existentialist and say, “Well, there's nothing at the end of any of this and there's no purpose in anything we've done.” We have to believe, I think, just to get through each day that there's a reason. I mean there'd be no reason to clean your house if you thought, “It's all death anyway,” so why bother? [laughter] But you still have to maintain your life because you're not dead. But long ago, I did get interested in this idea of the conflation of the erotic and the spiritual, the divine. I think I thought at the time that it was new. But I also realized I had read things like Teresa of Ávila, saints who described their encounters with God as a kind of sexual ecstasy, not just religious ecstasy. I also am fascinated with Augustine's confessions and his desire to want to be better, and at the same time, unwillingness to let go of pleasures of the flesh. Even my first book has an epigraph from, I think, Romans that says something like, “For what I would, that do I not, and what I would not like to do, that do I.” This idea that I'm aware of how I should behave, but I'm not behaving that way. That goes back again to these ancient Greeks, in the tragedies, the crime usually is simply that someone is behaving the way they feel they should versus how the state has decided they must behave. That ties into with the biraciality but also queerness. I grew up being told that I'm supposed to marry a woman and have a certain number of kids and that's my life. So what does it mean when you can't help it? If that's not how you can live your life? So you're standing at that very crossroads of contradiction. To be told that this is the way things are because of some God who's decided it's right becomes problematic because then being yourself is blasphemy. How can that be? It has meant that I've had this weird relationship to religious texts and religious thinking because I'm interested in faith and the idea of devotion to one person or one divinity or something. But I also feel as if it's not realistic. That spills over into how I conduct my life in a relationship with another human being because I don't know, I guess I want to believe in things like—and this was the problem, early on when I was writing, I was trying to write in my second book. I think my point was I was in my first queer relationship. I think I thought that I'm going to figure it out. I hadn't seen examples of two men in the public media and all that. I hadn't seen examples of two men living happily ever after together. But I thought it must be possible because that's what's going to happen with me. I was certain of it. But the deeper I got into the relationship and into the poetry writing, the more I realize that it's not that easy and good intentions aren't enough to keep people together. Love isn't necessarily enough to keep people together. I would have been astonished in my 30s to be told that you can love somebody and not be able to continue a life with them. I would not have believed that was possible. Equally astonishing to me is the lives of many people where they don't have love, but they continue to live with the person that ostensibly they love. But now I understand how much more complex it is to be a human being. So I think the poems, the poems have always been wrestling with that. That poem that Garth mentions, Hymn, which is a good example, the title is H-Y-M-N, as in a religious song, but of course, I also mean him, H-I-M. In that poem, I mean, basically, the poem is a cruising poem. It's a poem of going off and meeting a stranger and giving them a blowjob. But it's cast in this language of religious devotion, the idea that, yes, are you giving someone a blowjob? Or is that also the gesture of prayer? You're on your knees, as in prayer, which to me at the time seemed wildly blasphemous to even write, but I also was excited about it. At the same time, I'm aware that the question is there somewhere, like, “Is this just a way to justify this kind of behavior? If you see it as religious, as sacred, is it okay to behave in certain ways?” I'm really interested in the idea of there's religious faith, but then there's the faith of giving yourself up bodily to somebody in a dark room whom you don't even see. That's faith, too. That's a different kind of commitment. “But aren't they related in some way?” is the question I've asked? I've often had people avoid me after readings because I think people don't want to think about that stuff. And I understand why.

DN: Well, maybe as a lead into continuing this meditation, could we hear Fist and Palm and Somewhere It's Still Summer?

CP: Sure. Do you want them in that order?

DN: They don't have to be in that order.

CP: Okay. Just because the book opened up at Somewhere It's Still Summer, so let's go and read it. Here's Somewhere It's Still Summer.

[Carl Phillips reads from Scattered Snows, to the North]

And here's this poem called Fist and Palm.

[Carl Phillips reads from Scattered Snows, to the North]

DN: We've been listening to Carl Phillips read from Scattered Snows, to the North. Thinking of the Chimera created in the poem of Gabby's that you were attracted to, created by the goat horn penetrating the eye socket of the speaker, and similarly, almost a new composite creature of you and your younger self in Fist and Palm, I wanted, as a first step toward talking about your poetry's relationship to nature and the non-human, to ask about both the centaur imagery in Somewhere It's Still Summer and how in your prose you've described the poet as a minotaur, or like a minotaur. I'd love to hear about this notion of half man, half animal, which I feel like we've already been speaking about, just prior to you reading these poems. I'd love to hear about it in a general way, but also what about the centaur and the minotaur in specific, if there are particulars about their stories that make you choose them over a merman or a werewolf, for instance?

CP: Yeah. I hadn't thought about that, but I like that question. I guess the thing about the minotaur, anyway, which has a man's body by the bull's head, it was considered monstrous, not something good by any means, which is why it was locked up in a labyrinth. The problem with the minotaur, too, is that it eats all its victims and so it's quite violent and vicious. So fun there's the minotaur, then there's the centaur and the thing about the centaur, you could call it a monster but maybe it makes a difference that the minotaur, the body is a man and for the head, we have an animal so we don't have the kind of human rational thinking. The thing about the centaur is the top part is the man and the bottom is a horse. Yes, there's an animalistic body, but there's rational thinking that happens with centaurs. Centaurs in mythology were famous teachers of heroes. Achilles had a centaur for his teacher. So they were known as being extremely wise. But the other thing about centaurs is they're known for being super horny and unpredictable. There's a famous wedding they broke into, they go to the wedding and then they all carry off and rape the bride because that’s their horse lusty part. So of course, I’m interested in the tension between, and centaur in particular, rational thinking, knowing how we should behave but the other part that’s an animal with a big horse cock that just wants to do stuff with that. It seemed to me for a long time to be a good symbol for what it's like to just be a human being actually, even though we like to think, no, we're all rational. But I remember, it came up in the days when these weird sensational trials were happening on TV for the first time, the Menendez brothers and things like that, people would say, “How could this happen?” I never wondered how it could happen. I always thought, “Oh, people snap. They can know all about how they should be towards their parents. That doesn't mean they wouldn't kill them.” None of it is shocking to me. But I think it is to most people because we distinguish ourselves from animals instead of saying, “Well, that's always just being held artificially in check in some way.” Wait, what was the question? What's my interest in these mythological creatures?

DN: Yeah, I mean, just the reasons why you would choose these in specific.

CP: Yeah, because something like a merman, first of all, a merman doesn't have any, I understand, sexual parts. So there's not much that can go on there. I don't know how threatening they can be unless they have a trident or something. [laughter] But also, in particular with the centaur, I have a fascination with horses because of how massive and physical they are and this weird relationship we have to them in terms of riding them because it all seems, I've seen it in real life, it seems as if you're under control. You control the horse but there's a huge massive amount of power that can go awry right there between your legs and you just think that you have the ability to steer it around but that doesn't always happen. There's an exciting tension between unbridled power and rational control and the illusion that we have that control over an animal. All of it interests me.

DN: Yeah, that's great. Well, I want to spend a little bit more time with you as a nature poet and one of the things I love most about your poetry is the abundance of the non-human in it. You've said that because you were living on various air force spaces during the first 15 years of your life, always moving, that community was whatever could provide reliable company, and that was often not people, but books, animals, and trees. But the thing I love about this aspect of your poems is that it doesn't feel like the non-human is separate from you. Similar to the chimeras, there is a sense of inseparability in a way between the natural and the human in your poetry. For instance, in your essay Among the Trees, which is a meditation on your earliest memories of trees, that essay among other things is also primarily about human encounter among the trees, where you say, “What happened back there, among the trees, is only as untenable as you allow yourself or just decide to believe it is,” and, “What is cruising, if not a form of hunting,” and, “In a sense, the poems themselves are trees, or tree-like, in that they become a place where what’s difficult and/or forbidden can have a place both to be hidden and within which to feel free to unfurl and extend itself.” In this collection, many human experiences are evoked through non-human imagery. Memory is compared to a moth in a web in one poem. Trees grow quiet like thinking in another, or the line's “Little stutter skiing of plovers, lifting like a mind in winter.” You don't hesitate to anthropomorphize to imagine, for example, what a river might love. I wondered how you saw these non-human forces in relation to your own lyric self and whether you have an ethos or a set of parameters on what you will or won't put these forces in service of when you use them.

CP: It's funny because I don't like anthropomorphizing. I hate it when people say the trees waved at me and smiled or something like that. [laughter] But I'm aware, and maybe it's related to something we talked about earlier, about our human impulse to impose humanity on things or impose meaning on things that relate to us when they don't. I don't have an ethos about it. I mean, I love the natural world. I spent a lot of time in it. I don't think there are messages being given to us. I think there are messages, but they're not meant to come to us. They just are there if we want to see them. For example, if we want to look closely enough at a hawk making its way towards a fish that it can see beneath the water, that we can see the fish there, it can be seen as a lesson in patience, close observation. That’s what the hawk has to do to get to this fish. But also, as it goes down, it gets the fish and takes it away. None of that is an allegory about anything. At the same time, it’s hard for me not to think about the randomness with which destruction comes upon us. The fish is just there hanging out, and suddenly, is in the air and going to be eaten, for what reason? Nothing. Except it was there. To me, that’s a lesson that’s not intended as a lesson but it’s something that when I look at it, I think, “Huh, I feel like I’m being reminded about something of human experience in this natural world.” So it's like some cultures that seem to suggest that you need to try to be one with the natural world because we are also animals and that close observation can teach us things about how to live a life in nature, because we're in it too, even if we're in houses and apartments, whatever. I guess mostly my relation to nature is just to want to know, “How am I part of the constellation in some way?” I mean, I don't know. I was watching something that's mundane yesterday while I was waiting for my dog to come out of the yard, I saw one bee on a bit of clover. I just stared at it. It seemed important to spend time looking at it. But I didn't leave thinking about it. I'm not going to put in a poem. But it seemed important to remember that there's business and energy going on everywhere at any moment. I never really stopped to look that closely at something like that. I'm also a little afraid of bees so it's not my usual tendency to get right close to it. At the same time, sometimes I feel as if, “Well, we're all inhabiting the same world and it seems important to be cognizant of that.” I think it's such a human thing to want to build houses that shut out the world. We have AC so we don't feel humidity or we have screens so insects won't fly in. It's true. I don't want insects flying around in my house. But at the same time, I sometimes realize that is actually how it's supposed to be, that everything is intermingling. It's just artifice that we have property lines and porches with screens on them, that kind of thing. Again, I feel I might be straying from the natural world, except to say that it's really important to me, and I'm glad you brought up the essay about the trees, because for a long time, I've thought that it makes absolute sense that cruising happens in the woods a lot, and sure, partly because no one can see you. But also, it sometimes has seemed as if it's the most natural thing in the world to feel sexual desire for somebody. It's only in society that we're told it's not the most natural thing all the time, depending on whom you're desiring. There is a way in which being in the woods, so it feels as if, “Well, this is no less natural than a bird making a nest or a fox crossing your path.” Again, that could also be a rationalization for forbidden behavior. But I always ask myself, “Who's forbidding it and why?” Usually, not for any reason that is inherent to the act itself, but for how it offends somebody in some way. I don't know. I look to the natural world as a kind of its own moral compass in a way, its own way of reminding me that a lot of what I think of as established morality is artifice. We both have to live within its boundaries to some extent but I think it's important to also realize that they aren't fixed answers.