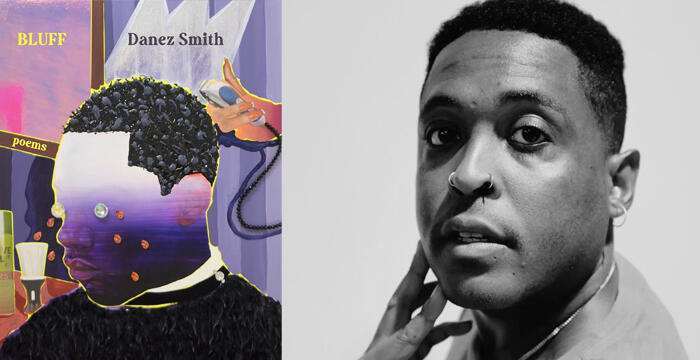

Danez Smith : Bluff

Danez Smith’s poetry is so many things, a poetry of resistance, of elegy, of joy, of care, of repair. Their poetry is Afrofuturist and Afropessimist. It’s nature poetry, decolonial poetry, queer poetry, a poetry that is archival and documentary. And it is also a poetry that questions poetry itself and even more so, questions the poet, a poetry that is continually in the process of self-remaking and unmaking, of forging and severing allegiances, a shapeshifting poetry, a poetry of mutual aid, a poetry reaching toward, and already singing from, an elsewhere and an otherwise. Nam Le for the New Your Times, speaking of Smith’s new book Bluff, doesn’t just suggest that this book is a major turning point for the poet, a volta within this poet’s evolution, but also suggests that Danez’s volta might also represent a turning point for American poetry at large. This twinning, of the self that is Danez to the poetry collective, feels prescient, as their poetry contains so much, and so much powerful self-examination, that it becomes an examination of all of us, for all of us, of what it means to be an “I” and what it means to be a “we.” Who better to lead us through than a poet like this?

For the bonus audio archive, Danez contributes something really special for us. As one of the six members of the Dark Noise Collective (along with Fatimah Asghar, Aaron Samuels, Franny Choi, Nate Marshall, and Jamila Woods), Danez reads a favorite poem from each of their five peers and follows each reading with a writing prompt designed for us and related to the poem just read. After five poems and five writing prompts, Danez reads a poem of their own too. This joins an ever-growing archive of supplemental material from Ross Gay reading Jean Valentine to Dionne Brand reading Christina Sharpe to Nikky Finney reading from the diaries of Lorraine Hansberry. To learn how to subscribe to the bonus audio and about all the other possible benefits of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today.

Transcript

David Naimon: It's hard to be a reader in 2024. Before getting into a good book, you have to somehow ignore your inbox, avoid doom-scrolling, break free from the algorithm, and then just when you're getting into it, there's an alert that pulls you back out. That's why a reading technology company, Sol, designed the Sol Reader, a wearable e-reader that helps you shut out the world and get back to reading. You put on the Sol Reader like a pair of glasses. Just slip it on, lay back, and see the pages of a book right there in front of you on an E Ink screen. Think of it as noise canceling for your eyes. No distractions, just words. Check out the Sol Reader at solreader.com to start reading without distraction. If you use the code COVERS15 at checkout, you'll receive 15% off your purchase of Sol Reader limited edition. Today's episode is also brought to you by award-winning author Melanie Cheng's newest novel, The Burrow. Following the members of the Lee family as they adopt a rabbit in the wake of loss and grief, the novel follows the family as they navigate hope and tragedy. Bringing together four distinct perspectives and one wide-eyed rabbit, The Burrow reveals the enormity of loss, long-buried family secrets, and how we learn to survive in a newfound world. Rajia Hassib declares, “The Borrow’s restrained prose and heartbreaking honesty capture the paradox of living with trauma.” In the words of Helen Garner, the novel provides "a calm, sweet, desolated wisdom." The Burrow is out November 12th from Tin House and available for pre-order now. During the weeks I was editing today's episode with Danez Smith, I was at a residency in Wyoming, the same residency I was at three years before at the height of the pandemic and with the same cohort for visual artists and myself. For much of the last year, I've been working on edits both macro and micro on my own manuscript with my agent and I was determined to have the final ones done and back to her before returning to Jentel, as I was hoping to start something entirely new there. But as I arrived, having triumphed in the first part of my goal, getting the manuscript finished, I not only found myself clueless about what to begin or how to begin, and not only that, but also feeling spent to, not blocked, but empty with all that mental space that had been dedicated to editing suddenly removed and with no time to adjust. Danez had just sent me their contribution for the bonus audio, which included, as part of it, many writing prompts they designed just for us. I decided to listen to this gift from them for the first time on one of the epic runs I used to do there three years before in a place called the Thousand Acres. Running with my bewildering emptiness up into those hills with the cows and the deer and the sage, I was suddenly filled with so much from three years before. When I was preparing for my conversation with the iconic Aboriginal writer Alexis Wright, who I was happy to see was one of the frontrunners for the Nobel this year, I did some investigating into songlines so that I at least had the most rudimentary understanding of them before we talked. One thing that stuck with me was how not only did a given Aboriginal community sing as a navigational tool as they moved along their traditional pathways, and not only did these songs act as repositories of knowledge of rituals, stories of animal and plant knowledge, the location of waterholes, and much more, but that the land itself acted as a cue to remember parts of the stories as you went, that you weren't just singing the land, but it was also singing it back, that the memory of it was held by you and also by the land back and forth. I was reminded of that as I jogged up into the thousands with Danez in my ears because as soon as I did, as soon as I returned there, all the circumstances of the world from three years before rushed back to me as I remembered and moved through the landscape for the first time again. I remembered that back then, I was preparing to talk with Rosmarie Waldrop and that I broke down crying on a run contemplating it, I was thinking about her shattering poems about her longtime partner poet Keith Waldrop and how he didn't recognize her anymore, how she had been a child and young teenager in Nazi Germany, with parents who were supporters of the regime, fleeing her family, coming to America, and alongside all her incredible poetry through the decades, dedicating her life to translating the work of the Jewish writer Edmond Jabès, who himself lived in exile from Egypt. But just as my re-encounter with this land was triggering these memories, at the time, three years ago, Rosmarie’s poetry itself was triggering my ability to feel and be wracked by all sorts of feelings that I think are easier to shove down in the day-to-day of making it through when you're not lifted out of your life and placed in a privileged position of having a residency. The Trump presidency that had just ended earlier that year, that we were 18 months into a pandemic, and not just the fear and isolation of that, but also that it was clear we had no interest in facing or addressing why we've been at an elevated pandemic risk for the last quarter century. The heat dome that had happened the year before in Portland, where it reached 118 degrees, where millions upon millions of sea creatures cooked in their own shells, a temperature that seemed unfathomable in the Northwest, and is a higher high than many places have ever experienced in the Southeast, and a fire that came quite close to the city limits with the air pollution so high that it was higher than the top of the scale, where a lot of my priorities clarified in an instant as the first thing I got ready was a small suitcase of my podcast supplies in case we had to flee. All of this rushed back with Danez's soothing, inspiring, warm, funny, fierce voice accompanying me to the top of the ridge. Where this time, I had another good cry about Gaza and Lebanon, to echo that cry in the same place years before, and all of this happening before the election results. Me now riding this, up in the air at 30,000 feet, between Wyoming and Oregon, bracing myself for the next four years, I confess I was feeling spent before November 5th. Like, I needed to find a new pace for my life for the podcast to find a new, better life-work balance. But the election results gave me unexpectedly a burst of reserve energy somehow about doing this. Thinking about how the show has invited in and been porous to the world and its politics as they've been unfolding, whether our relationship to the more than human world or around questions of decolonization or of race and gender, and the unfolding live streamed horrors we've seen non-stop in Palestine for the last 13 months, questions of art and representation in relation to any and all of these things, yes, but also just questions of living through it all too, of making it through, the podcast has been a way through for me, and I hope it has been for you too, and maybe even a small part of all of us figuring a way out too. I feel beholden to so many of the people who've been on the show, whether Dionne, Christina, Canisia, and Billy-Ray, Nikky, Natalie, Layli, Brandon, and Bhanu, Adania, Viet, Hélène, Naomi, Jorie, Solmaz, Kaveh, and now Danez, knowing they are all out there, asking all these questions alongside us, feeling the feels alongside us, I can't express how much that means to me, and honestly, I can't think of a better guest, a better conversation, a better artist, a better person to present to you today within the long shadow of all of this, with poetry that somehow so skillfully confronts and transforms every one of the things I've mentioned, the entire litany of things I've listed, than today's guest, Danez Smith. Before we begin, indulge me for a little longer while I do the thing that I wish I didn't have to do, that I honestly feel most self-conscious about doing, which I'm most sick of hearing my own voice saying, and that is asking you to consider joining the Between the Covers community as a supporter of these conversations, whether for a short time, for a long time, or as a one-time thing. I'm only here because of you, and that isn't an exaggeration. Today's guest, Danez themself is a Patreon supporter. What I jog to in the Thousand Acres is their 30-minute contribution to the bonus audio archive, where they read poems by each of their five peers in the Dark Noise Collective, from Franny Choi to Fatimah Asghar, to Nate Marshall, and then they create a writing prompt for us after each one, a prompt inspired by each poem. This joins wonderful contributions from Ross Gay to Natalie Diaz and many others, not to mention a gazillion other things to choose from, including the book-length anthology from Jewish Currents, called After October 7th, with writings from Noura Erakat, Fady Joudah, Hala Alyan, Arielle Angel, and Dionne Brand, among many others. Past guest Anne de Marcken, who just won the Ursula K. Le Guin Prize for Fiction, she helms the most incredible press, the third thing that Le Guin would have adored, with books that are also art objects made with immense care that she's offering to supporters. There's always, when it isn't sold out, the Tin House Early Readers subscription, receiving 12 books over the course of a year, months before they're available to the general public. Or maybe there's just been a conversation or a series of conversations that have felt like life rafts, that have felt like a way across the narrow bridge, or have felt like a way of connecting and feeling connected. If so, consider joining us. You can check it all out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now, as we gather ourselves and reach out to others to confront the years ahead, I can't think of a better person and poet to lead the way than today's guest, Danez Smith.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest poet, writer and performer, Danez Smith, came to poetry through theater and performance. Their first poem written for a high school acting class and their poetry coming to the forefront in the world at first on the stage, where they have twice earned the title of Individual World Poetry Slam finalist, as well as a two-time Rustbelt Individual Poetry Slam Champion.

Danez Smith: Four times.

DN: Four times.

DS: Wait, how many times did I win Rustbelt? Hold up, one, two, three. Yeah, I think four. [laughing]

DN: And a four-time Rustbelt Individual Poetry Slam Champion. They've also served as festival director for the Brave New Voices International Youth Poetry Slam. They're one of the co-founders, along with Nate Marshall, Fatimah Asghar, and others, of the Dark Noise Collective, a multi-racial, multi-genre poetry collective whose work spanned poetry, music, dance, and performance. They attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison as a first wave hip-hop and urban arts scholar and pursued an MFA at the University of Michigan. Danez was, for the longest time, co-host with Franny Choi of one of the great poetry podcasts VS where they talked and laughed with some of the great poets of our age, including past Between the Covers guests Ada Limón, Ross Gay, Morgan Parker, Tommy Pico, Kaveh Akbar, Hanif Abdurraqib, and many, many others. Their first collection, Insert Boy, was winner of the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry. But it was with their 2017 collection, Don't Call Us Dead, where they leapt into a new orbit within the public poetic imaginary. Winner of the Forward Prize for Best Collection and the Poetry Society of America's Four Quartets Prize, a finalist for the National Book Award for Poetry, and heralded as an essential read by National Public Radio, Former US Poet laureate Tracy K. Smith says of Don't Call Us Dead, “Danez Smith's is a voice we need now more than ever as living, feeling, complex, and conflicted beings. These poems of love extend beyond the erotic into the struggle for unity--not despite the realities of race but precisely because of what race has caused us to make of and do to one another. Don't Call Us Dead gives me a dose of hope at a time when such a thing feels hard to come by. This is a mighty work, and a tremendous offering.” Their third collection, Homie, was winner of the 2020 Minnesota Book Award and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, the NAACP Image Award for Poetry and Publishing Triangle's Thom Gunn Award. Their work has appeared everywhere from The New Yorker to The New York Times, from The Pushcart Anthology to Best American Poetry, from PBS NewsHour to The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. A Cave Canem and NEA Fellow, they have two books coming out this year. Arriving this November is Blues in Stereo: The Early Works of Langston Hughes, lovingly curated by Danez, who also serves as a guide through the work. As Hanif Abdurraqib says, "In Blues in Stereo, we get to witness a young poet figuring out the work and the self in tandem, clearly brimming with potential, turning corners as they arrived. This book is not only a gift for what it gives us of Hughes, but additionally, it is a gift to any poet working at any stage of their life and career, needing a reminder that there is more to reach for.” Danez's other book is the one we're talking about today, their fourth poetry collection out from Graywolf and entitled Bluff. With starred reviews in Publishers Weekly and Library Journal, Sarah Michaelis for Library Journal calls this a not to be missed collection that will surely be one of the best of the year entire. Past Between the Cover's guest Nam Le for the New York Times suggests, “Bluff represents a notable turning point for the poet — and maybe for American poetry as a whole,” saying, “the main shift may be a signal one in American poetry, one we're privileged to witness. It's a shift from polarity toward antinomy, from the ruling sense of either/or to the unrulier all-of-it-all-at-once. This is embodied in Smith's poems of place, in which Minneapolis is ‘my murderer, my mother/-ship, my moose heart, my mercy.’ It's where George Floyd was killed, but also where the ‘beauty of the food drive makes me cry’; where ‘my neighbors are dying./my neighbors are killing’ but also where ‘we became our own cops.’ In these searching, stunning poems, Smith metaphorizes city into body politic, showing us the interstate running through all our hearts; demonstrating that we all contain protest and police, cowardice and commitment, money and kindness, looting and food drives. There's no poem to free us and, anyway, there's no freedom from ourselves, no future without slave ships in its past, no world where God, reason/the stars didn't sign off. In the face of all this, what is hope — or despair — but a bluff?” Welcome to Between the Covers, Danez Smith.

DS: Ooh, oh, my God, I've got one of those intros. [laughter] I'm sorry, I'm looking serious, but David, I've told you so many times, I'm such a fan of your brain and your curiosity in this podcast. It is my walking partner. As I go past my favorite trees in the neighborhood, I'm always listening to your voice. It is a pleasure. I was listening to Isabella Hammad's interview yesterday which is brilliant by the way and so necessary and so needed for these times. I can’t wait to pick up her book. But the fan in me was so giddy, was like, “Oh, my God, I’m getting one of those tomorrow.” [laughter]

DN: Well, it’s a mutual fandom. I’ve been so excited for this. So let’s get going. Okay, so in preparing for today and listening to and watching a lot of your performances and interviews over the years, one thing I really love about you out in the world in relationship to your own work is the way you look back across your work as if from a high vantage point—I think as if we could say from a Bluff, but even before this book Bluff—and making meaning of it and from it, perhaps as a way to see where your poetry was going and whether you still wanted that to be the same trajectory going forward. To look at it with the benefit of time and of distance and to see what still seems visionary and what seems now limited. You do this in many ways. For instance, for this year's Eric Williams Memorial Lecture, you said your first two books were born of thinking you were going to die, first as a Black man in America and second as a Black gay HIV positive man in America. But at a poetry event in Kalamazoo, you also talked about how your first two books were working through and moving from boyness to a they/themness. That's something I want to talk to you about later on today. But before we open Bluff together, let's talk about its arrival in relationship to you and your own self-narrative and self-revisioning. Because when I think about moving from a he-ness to a them-ness, one way many might think about this is as two different framings of individual identity. But when asked if your "they" was singular or plural, you say it's the latter. I feel also this movement toward the "we," but also toward defining what the "we" is and isn't, too. You once described your Don't Call Us Dead book tour as “yelling at white people for money.” [laughter] Homie is a book where you instead wanted to write for the people you loved. At a Homie performance that I was at at the Tin House Summer Writers Workshop, you said prefacing some of the poems, something like, "White people in the audience, these poems are not for you." But perhaps coming full circle, this summer at a reading you read, “dear white america,” one of the poems you're most well known for, but this time you read it with the intention to reclaim it, to reclaim it from, in your words, the dirt on it. I'm personally a sucker for this art making that's also unmaking and remaking, which feels like a self-making and unmaking and remaking, but also a negotiation of you with the world and the world of your readers. My long question is hoping you would talk about this, about this relationship to you and your work publicly, but also thinking about it yourself, and also make a first step toward orienting us to Bluff in placing it within that process.

DS: I think it's all about moving, I think Nam Le maybe had it really right in his review, moving towards an embrace of nuance and complexity. I think growing up, very Christian, growing up Black, growing up many different things, I think there was this idea that if you are just this way, [laughs] if you are just in a certain particularness, if you stay in your lane, there's safety there. But there's not much movement within that safety. It's just this line that you follow in order to guarantee life. Don't get too far outside of the line. Even in the moving from he to they, there's a lot there in terms of gender. I think they, for me really speaks to maybe a more Indigenous concept of two-spiritness, of recognizing both the masculine and the feminine, of recognizing that my male ancestors, for better or worse, are as alive in me as the wonderful lineage of women that I come from and who I feel a home and a particular kinship haven't come from their blood, but also that there's a commitment to community there. I think for some of us, and I think this is very much coming out of The Black Arts Movement for me, there is a wonderful “we” that is holding behind the “I” even maybe going to the Rastafari concept of “I and I,” the “I” that is myself, the “I” that is divine, and the divine, or in God, there is all of us. There's this “I” that I come out of, not just an “I” that is siloed. For me, there is that multiplicity within they-ness. I think that multiplicity speaks more than just to gender, even community, but a multiplicity across time as well. I am in community with my older selves that I haven't arrived at yet. I am setting up gifts and problems for them to receive sometime in the future.

DN: I love that.

DS: [Laughs] Yeah, even little stuff in my day just as a quick example, when I go to the gym, I say, “I'm loving an old Danez.” [laughter] I'm making sure that he has a nice body, that they have a nice body that they can move around. But I'm also in community with my younger selves as well. I think of two brilliant Black women writers. When I say that, I think of Angel Nafis, who in her brilliant poem, Gravity, which is tattooed on my back, says, “I'm ninety. I’m a moonless charcoal,” we are always this expanse of selves. But I also think about Toi Derricotte, who every year when I was at Cave Canem would give us the talk about go and write your hard poem. The hard poem for her was often coming from a wound, from a source of trauma, but it's the poem that you can't stop writing your whole life. You keep on returning to the wound as an older, more experienced self. The hard poem is different when you write it at 20, at 25, at 35, at 47, the rest of your life, you'll always have new eyes on which to see it, while you can also remember what it was like to see it from those older eyes that no longer fits you. You can respect all of it and you can learn from all of it. I very much feel that self-community across time. I think about it in my relationship with my family, with my grandfather, that's a whole nother topic, but who, even within the space of a week, was a very different man Monday to Friday than he was on Saturday when he would drink. I learned how to compartmentalize across time that relationship to him. I just think there's such gifts in reflection and such power in prayer. I think maybe they're similar things, reflection and prayer, just facing in two different directions of time. In reflection, I can think back and learn from who I was and where I've been and what I thought. While I can't revise my actions, I can revise my forwardness and I can take apart what I've done, what I've said, and learn from it and really touch on it and see, “Is that true. Was that a momentary truth that I needed right then? Is it going to last me? Do I need to put some of these thoughts down and pick some new things back up?” Prayer, which is often like asking the future for transformation, is often informed by that past as well, “Please let this become ephemeral. Please let its temporariness be true, let me escape what is feeling current and constant, or let some change that has no evidence in my life come about right now, soon.” I think about that. We're often begging time. We can't change it. There's one thing that maybe we can bend towards, but I don't even know if I answered the question. [laughing] But whether it's the “I,” whether it's the community, I realized late in writing Bluff that really what I was troubling was time. I thought it was location and I thought it was language and surely, those things are true. But what I'm really begging for is an interruption in the oppressive patterns of time that we still seem to be stuck in.

DN: After publishing three books in a little over five years, you had a several year period between Homei and Bluff where you didn't write, not only because you weren't sure what else you had to say, but where you'd become cynical about poetry. Again, in your Eric Williams Memorial Lecture, you talk about how you've characterized the poetry world as in two camps, Dear Diary Poems and Fight The Power Poems. But that when a broke poet writes a Fight The Power poem, that then is showered with money for it where you can buy a car with the poetry money, it can mess with your head. In an event you did with Patricia Smith, you talked about navigating your sudden shift in profile and exposure, where you became quickly one of the most high-profile poets in the US with your second book, and about the white gaze and white salivation over your work as elegy and as protest. I wonder if these years of not writing, if part of the story of that not writing is figuring out not just whether to write, but if you did, how to take it back, perhaps the way you want to remove the dirt from “dear white america,” to frame it again, and maybe for the first time. But you've also said that you've had a troubled relationship with your last book, Homie, even though it is the book that is explicitly addressing those you love, which also made me wonder if there's something around Homie that needed to be sorted out too, and what that might be, but all of which to say, talk to us about the period of not writing and then re-engagement.

DS: Right, because in Homie, even from the title page, you have this door, this limited access with the two titles. I think my problem with Homie was really another thing about time. It was rushed. I learned a lot from that. I think my press did as well, just about what it's like to work with me. The background of that was not too long after Don't Call Us That came out, I had sent Jeff Jeff Shotts—the beloved editor at Graywolf, shout out to Jeff—a package of maybe 30 pages of poems that was just like, “Oh, I just want you to have a look. Here's where my mind seems to be going.” They were very excited about it and what I got back was a contract. It was like, "Oh my god, we would love to put this on the contract." At the time, I was like, "Oh my god, absolutely yes, look at this endorsement. I'm so excited to keep on working with y'all." But it also put a date on it, a due date and I realized now I had the power to push it back if I would have wanted to, but I felt allegiant to that contract and to finish in these thoughts and what arrived on the other side of that contract was a very intense bout with writer's block and I wrote crap. I did one of the worst residencies in my life. It wasn't worse, it was okay, but I was just not in a creative space. Everything I was writing was crap. What I call my mountain sister, the poet Monica Sok, was at the same residency. I'll never forget, I taped all the poems on the wall and she came over and was looking at them and just the faces she was making while reading some of these poems. Oh God, I had this really awful poem about grace that I think I showed her, I was really excited about, and her face said everything. [laughter] I was just like, “Maybe we're still at the drawing board a little bit.” But I realized I couldn't rush the thought. I don't think poetry is something where I can just pump it out, where I can say, "Okay, I'm writing a book about friendship," then just write 50 drafts really quick about friendship. No, I think it requires a long time. I'm grateful to the poems that take 15, 20 minutes to write. I have those poems. My poem Dinosaurs in the Hood was that poem. It was 15 minutes in an airport. But I'm also grateful to the poems that take years of thinking. There are so many poems like that in Bluff for me where I knew I wanted to write a poem, let's say, about rondo. I knew I wanted it to encounter the freeway in some way, but it took five years for the right sentence to start from to show up. Even if I could see the poem in its shape, the language needed to be right. Same with the poem Two Deer in a Southside Cemetery. I drove past this deer all the time and you see two deer in a cemetery all the time, you can't help but think, “Oh my God, they need a poem.” [laughter] There's certain things that just scream at poets like, “You must write about me.” But the language, once again, wouldn't come. I had to be patient. So poetry really requires patience and silence, as Carl Phillips would say. I'm very grateful to his My Trade Is Mystery in the essay about silence in there for really giving space for taking cold and gratefulness in the silence in the road between poems, the poems are the plateau. After Homie, I think now I like it, now I can see the mountain and I love what Homie does for other people is actually other people's love of that book that convinced me of it because while myself as the maker was maybe frustrated with it, and I think it was maybe not even frustrated with the poems, I do think it's a good book. I was frustrated with the process. I don't call this dead. It was such a beloved process to make that book. There was a lot of that. I'm trying to save my life energy, but there was also just a long meditation with the work and being able to sit with it and being able to let it breathe. Writing a poem like “summer, somewhere” was just such a long meditation that was written over months. So really being able to wait in the work and not rush, the waters were calmer. With Homie, it was a little bit more of a rushing river. You got to get this done, you got to get this done. Because I think I was just dealing with grief after grief after grief, Don't Call Us Dead was running around yelling at white people about race, but it was also me coming to terms with my own mortality and shouting from the rooftops, like, “Let me tell you about this diagnosis I just got.” I can realize now that it wasn't a really kind act for the self. With Homie, there was so much love there, but there was also the grief of my friend Andrew passing and his suicide and my own suicidal ideation and attempt. While there was such a grand appreciation for friendship, I think I was still unstable writing that book. I don't think I was in my best self. But here we were writing it and then performing it. At Homie, I didn't really get to tour it. A year, a month after Homie came out was the lockdown. But I was grateful. I got to do a little bit of touring and very intentional touring, doing shows with friends across the country. That was beautiful. But then I went from grief to grief to isolation and we all went into isolation. After that, then George Floyd gets murdered by Derek Chauvin, assisted by the rest of the police that day. Who could think of writing? I mean, I didn't write for all of 2019 after Homie, which I thought was maybe normal, a year wasn't too bad. But then lockdown happened, and I really couldn't think of what to write. I was just drinking and smoking all day, that damn day. Then the uprising start following the murder of George Floyd, and I couldn't think of writing anything, especially not poetry. I wrote some prose then, an essay that would go on to become Minneapolis, Saint Paul in this book, and I only wrote that, I think that was for The New Yorker. They reached out and said, “Would you write something?” I only wrote it because my partner at the time encouraged me to and said, “You're here. This is something that you can do. If you don't do it, somebody else is going to do it wrong. So I need you to sit down and spend some time diving into the language and trying to make sense of all this.” It was only a bare encouragement that I did that. But otherwise, I just didn't have anything left to say. For a while, I felt fine with it. During the uprisings, I felt like my energy shifted more towards action than it did towards language, especially the preciousness of poetry. I think it felt too urgent for poetry at the time. I think poetry can be urgent. I think I've had moments in my life where poems come out urgent. But I think I realize a danger in that. Even thinking about the meteoric rise of my profile, part of that was writing the poem “not an elegy for Mike Brown,” which I posted on Facebook the day after his murder, which then is one of the poems that catapults me into this other sphere. I think I wanted to be careful this time. Maybe there's a little bit too much self-flagellation in this book, although I do think the performance of that exfoliation might be productive for myself and maybe for readers. I really wanted to be particular with language and what I think language does. This book was me rescuing my relationship to poetry and kind of saying, “Okay, you've been doing this now for 20 years, 20 years into a relationship, it has to be a different relationship than it was when you first started, so why are you coming to poetry and what do you think poetry can do? What are its weapons, what are its failures, how are you complicit in that? What are your dreams for it?” I just had to re-meet poetry and I had to come to terms with myself as an artist in a way that now on the other side of it I feel very free. I'm grateful to Bluff. It cleared the space for the things that I'm writing right now. After you married somebody for like I think somebody said like after seven years, just go to couples therapy and check under the hood. [laughter] So I think it's very much that. It was just me checking under the hood of my relationship to poetry and also my relationships in Minneapolis, which had never really been too evident in my poetry. I felt like a poet of nowhere in my first three collections, it's very hard to see place unless there's a couple of times where it's like, “Oh, maybe they live in Oakland,” or “Oh, they're going back to Minnesota.” But other that, place is very absent from my work before then. I think a lot of us who live where we grew up have an awkward phase with it or maybe you want to flee it. That's what I did many times. I was like, “I got to get the hell out of Minnesota,” and then I'm gone for two years, I'm like, “I absolutely must go back.” After the uprisings, I really didn't want to leave. I loved it here. I'd met the person who would go on to become my husband. I felt reconnected to community in a way that moving away and being on tour so much is interrupted. I had a deep time here for the first time in a very long time. Then I was pulled away by a fellowship that I had applied for, the Princeton Arts Fellowship. The beginnings of Bluff come from not only wandering back into my relationship with poetry and figuring out what works and what doesn't, but it comes out of an extremely missing for Minneapolis and St. Paul and missing my people after such a long period of mourning and possibility that we went through with the uprising. I think that brought me back to love. Do I still love this art form that I've held onto and that has held me for so long? How do I also make tangible the love and also, on the other hand, frustration that I have for this place that has raised me and helped me?

DN: I just want to mention one really incredible thing you said in a Madison Wisconsin radio station probably four or five years ago that I think is related to you speaking to how you found your way back to words and maybe taking them back from the way sometimes they were being consumed or framed, which was by asking yourself as a way to check in with yourself, “Could I read this poem to Trayvon Martin's mother?” which I think is just a useful and brilliant thing maybe for writers listening to figure out what that barometer would be for them, who could they read their poem to?

DS: Yeah, you need to be cautious. I mean, I think there is a certain amount of fearlessness and risk, of course, that has to come with writing. When we teach writing, what we're teaching people is how to take big swings, how to go for those risks. But in the same hand that takes the risk, there must be caution. There must be a fear of hurting the wrong person. Could I read this poem about Trayvon Martin to Trayvon Martin's mom? What would she think of this? Would I only reanimate her grief? Would I make the wound larger? Or would I offer her some type of healing? If I've written a poem in a way that it can be taken and commercialized and used for purposes that I think go against my liberation, then I have not written the right poem. I think there, with Bluff, the tone of it is very different because I want nothing to be misconstrued. It's more than the metaphors and the images. I think Bluff very clearly has a mission statement. It's because I want these poems to do something in the souls of the people who picked these poems up. I want us to look at our hands and wonder about the possibility of them. I want them to think about our collective responsibility to ourselves and to our words and to our communities and to our collective future. I couldn’t do that, only worrying about beauty, only worrying about Crap, there had to be a caution. The caution led to inspire passion, but I had to write these poems in a way where there is no argument about what they mean and what they believe in.

DN: Well, I definitely have an attraction to this public engagement with one's own process, but also with one's own imperfections. One of the main things that kept me interested in doing the 2022 limited series on the work of Ursula K. Le Guin to talk about one writer for over 25 hours with 12 different people is not because she was a perfect visionary, but rather that she had this really compelling and public relationship to her own limitations, where at the same time she could be utterly visionary and also somehow behind the curve on the same issue, but over the course of the following decade, think her way through a self-revision in public, a revision that never erases or hides the original, but rather very generously leaves evidence of the making and the unmaking as she changes. Yet she also went back into her world and changed the rules of them too. I was excited to see when I opened Bluff that your latest book takes all these questions about you and your audience and about poetry into the poetry. Many of the questions we have for you today from other people are asking the same question to you about this but in different ways. As a first step toward talking about revisioning within your actual poems themselves, we have a question for you from past Between the Covers guest, the poet Ama Codjoe, whose debut full-length collection, Bluest Nude, is amazing and, unsurprisingly, won the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize, whose past winners include C.D. Wright, Alice Notley, Patricia Smith, Adrienne Rich, and Henri Cole. She actually asks you two questions, but for now, let's hold off on the second one, hold it in our minds and we'll return to it later. We'll answer the first one now, but here's a question for you from Ama.

Ama Codjoe: Hi, Danez. Congratulations on Bluff. What a magnificent title and what a tremendous, tender, curious, biting, ferocious, poignant collection. There's so much to admire in these pages and I love the risks that you're taking in terms of experimentation and form. I wanted to ask a few questions regarding space and place. The first is if you could speak to the experience of reading your work in progress, so this is writing that you shared about your hometown with a hometown audience, and I know this because it's in the book in this essay My Beautiful End of the World, so I'm wondering how that experience made its way into your revision process, and if there are a few behind-the-scenes stories that you could share from that experience. Secondly, I was curious just more generally about geography and form and how they're brought together in this book. I'm thinking about a poem “rondo.” I have made up a myth that maybe depending on what side of town you live on, you say it differently. But this merging of place and history and visuality that's happening in many different ways in the collection, I wonder if you could just talk about that, how that came to be or what that kind of meditation has brought or wrought. I am so grateful for your work in the world, for your presence, for your aliveness. Thank you, Danez.

DS: Thank you, Ama. Oh, I love her. I was just speaking her name the other day, and I also know another adamant listener of Between the Covers, so it's nice to put the Patreon talking to each other. Okay, so the first question about the work-in-progress reading that I did. I did that with a local or cultural speech, which is run by one of my best friends in this world, Tish Jones. She has always made abundant space for me and my work in her practice. I'm very grateful to her. I love teaching for her and all the things she does to care for and love on our community. That was a beautiful event. I did that event because I missed the live editing that happens in the spoken word in slam space. There is no greater editor than the encouragement or the silence and disinterest of an audience. I miss back when I was starting, I was so involved in slam and going to open mics and stuff like that, but you're getting constant feedback. But at a slam, you're literally getting numerical feedback. The judges, as random as they may be, are letting you know what hits a general audience. So, sometimes the answer is it just wasn't the right night for you or the judges say you need to perform it a little bit better. But if there’s one thing spoken word poets know and slammers know is that you have to go back to the page. Sometimes you only get funky as your last cut. So it's like either you go make the poem better, you go write a better poem, there's really no option. The further I've gotten into my career, the less access, not less access, but the less I participate in those spaces. I try not to take up too much space as large. I still go to open mics, but I don't always want to be the one that gets up. I wanted to have my community's eyes and opinions on work that is about them. They also do an open mic that I love the format called Re-Verb and at Re-Verb, whoever performs at the open mic has the option to ask the audience for feedback. It's a beautiful way for younger artists especially to come and get that live generous feedback about what they did well about what they could do better. It's wonderful because it makes poetry not just this showing of products, but I think it returns us all to our process. The reading was fantastic. We did a couple of different things. We did some live feedback of just people throwing hands up and telling me things. We did small groups on a couple of different poems. We had hand packets of poems and asked folks to just get in groups that I think like five or six and mark them up together and talk about what they did. I got to take all of that back home. Some of it was super useful and transformed the poems. Some of the poems stayed the same, some of them, maybe something in the feedback asked me to go and write another piece. I think one thing that probably happened the most was the essays in the book really expanded based on that feedback. It made me, I think, write in ways where I wanted to expand maybe the view of who is in Minneapolis and these poems, and then these essays, the Minneapolis, Saint Paul poem didn't have the litholine poetic things before that session. It was really just a checking point for me to say, “Okay, how do these people who are in the poems respond to them? How do they see themselves? Have I misrepresented us in some way?” There was a lot of affirmation that came out of that, that I knew I was on the right track. There was also a little bit of argumentation. I got to really wrestle with myself. I think that and a talk that, once again, my friend Angel Nafis gave me sort of, if you think the book is self-flagellating or deals in regret, no, oh, you should have seen the first drafts of it, [laughing] there was maybe no room for optimism or hope. It was just like, “Oh, my God, I did such a bad thing. I wrote poems,” and the way Angel put it to me was that, “Oh my God, that's just a dust. It won't do anything, it might be temporary, but it won't feed anybody.” From Angel and from that session, I think is where the optimism of the book comes from; the pointing towards hope and not just sitting in the doom of pessimism. I love pessimism because I think it keeps us sober and keeps our eyes clear. But if there's no optimism, what's the reason for getting out of bed in the morning? I needed those two things to be held together. I think that session was a good reminder that my community is not static, that we are still living together and there's a future that we're still building together. Why not, in the room of your pessimism, just make a window of possibility of which to leave?

DN: We have another question for you. But before we hear it, and also to set it up, I was hoping we could hear the first of the “anti-poetica” poems, then if you read this poem, the longer image text poem “on knowledge.”

DS: Okay, first poem in the book, “anti-poetica”.

[Danez Smith reads from their latest book, Bluff]

This is “on knowledge.” For everybody listening, because that's what you do with podcast, this poem has texts that normally is in a black box and sort of bouncing around the box a little bit and escapes the box at some point. Big black box [inaudible].

[Danez Smith reads from their latest book, Bluff]

DN: We've been listening to Danez Smith read from their latest book from Graywolf, Bluff. This next question is from the poet Evie Shockley, who was the guest of yours on the VS Podcast, an episode called Evie Shockley vs Gathering. Evie's latest book, Suddenly We, was a finalist for the 2023 National Book Award for Poetry, and the judges' citation said, "In suddenly we, we are reminded of our collective entanglements, set against the backdrop of historical, societal, and ecological upheaval, a shared reality that shakes us from modern individualism. Through her ekphrastic responses to creatives and iconoclasts as well as her own innovations in poetic form and page and sonic play, Evie Shockley’s collection invites us into the continual revelation of that interconnectedness that, if we had the courage to see, just might agitate us to act.” Here's a question for you from Evie.

Evie Shockley: Hey, Danez, it's Evie. I hope you can hear me. I am speaking to you literally from the southern coast of France with the Mediterranean crashing against rocks just below where I'm sitting. I was really thrilled when David wrote to ask if I would be willing to pose a question to you for this interview because, one, I knew that meant I would get to read Bluff in advance, which was exciting. Two, I was really curious to see what it would be like for you to be the subject of an interview of this sort given how wonderful you and Franny were as interviewers in your own right. Yeah, I'm really happy about this opportunity. What I want to ask you about Bluff. Bluff is really a tornado of a book, and I use that metaphor very intentionally. A tornado is very destructive in certain ways, but it's also oddly, if not precise, particular maybe, just outside the path of a tornado, things can look like nothing was touched. There's also the eye of the storm where things are calm, even as everything else is whirling around, around that space of calm. My mom once told me a story about a tornado coming through West Tennessee where she grew up and said that it picked up a cow from one pasture and put it down, still alive, basically unharmed on the other side of the river or something like that. So I'm thinking about that aspect of tornadoes, their ability to be both destructive and yet not wholesale destruction. Bluff is a book that really seems to, in one sense, have it out for poetry, yet it does this dance in which poetry comes out at times maybe unharmed, still able to do what it does. I was interested in that, that kind of doubled movement of the book. There are these anti-poetica poems with amazing lines like “no poem to set you free” that seem to warn against us putting too much faith in poetry and then that line comes at the very beginning of what is a very long manuscript of poems. It's a line that cautions against putting faith in the thing that you yet invite readers to stay with, with you. I was interested in that, not in a kind of "got you" in a contradiction kind of way. I mean, of course it's contradictory, but I'm interested in how you think about that contradiction. I'm wondering where you sit in relation to whatever your thoughts are about the contradictory move between putting faith in poetry and distrusting what poetry does. There's this wonderful graphic poem early in the collection called “on knowledge,” one part of which is a black box surrounded, bordered by what at first looks just like a decoration until you realize it's the capital "I" just going all the way around the edges. I'm thinking about that "I" and the eye of the storm of a tornado and the lines from another anti-poetica that say something like, oh, yeah, here it is, "The problem with being a poet is once others know." You got me thinking a lot, Danez, and I’d love to hear what you might say about the relationship among these ideas that I’ve raised around poetry and being a poet as you put it before us in Bluff. Thanks so much as always for your beautiful, powerful, just fierce work and for being somebody who I can't imagine 21st-century American poetry without. Peace.

DS: Ooh. Oh, wow. Okay, I'm going to collect myself. I can't listen to Evie talk to me sometimes without tearing up. She said a very kind and true thing to me at Furious Flower recently when talking about the poem "less hope" in her lecture or in her presentation that the poet was too hard on themselves and I think I needed to hear that. I don't think I'm that hard on myself. I think I believe in poetry if I can release 130-some pages of it into the world. [laughter] But I talked earlier about that exfoliation that I do think needed to happen and maybe in ways becomes a performance of how do we shed. When we talk about decolonizing the mind, how do we remove the mind from certain formulations and economies and configurations? How do we shed a skin? I think a lot of what's happening in Bluff, not just in the arguments about poetry, I think it happens even in its relationship to violence, there's a lot of space for disagreement here. Thank you for that question, Evie. I think poetry is big enough for me to beat up on it and I wanted to test the limits of both poetry is not a luxury and poetry does nothing. Maybe those two thoughts and consolation and really ask what does poetry do? I think the answer I came to is that poetry itself is not sufficient. But the way poetry has the ability to transform one's relationship to your own humanness and the humanness of others and to life and to nature and to the possibility of things and the future and of God, both with a big G and a little G and the God up there and the God everywhere, I think that's what poetry's potential is. I think that's what all arts potential is. I love arts for art's sake too. I'm not going to beat up on that too. I love a weird self-obsessed poem. [laughter] I love a weird Jean Valentine poem, that I don't know if Jean necessarily has political aims in the same way and go on the mountain, but goddamn it, if I don't understand something about living after coming out of that poem, that's what poetry does. That's what poetry, at its best self, for me, that's the volta that we create in the spirit. When we say, “Poetry changed my life,” you don't mean that poetry fed you, but you mean that a poem gave you some type of belief that helped you tie yourself onto tomorrow and let it take you wherever it's going to take you. When people say, “Poetry changed my life,” you say, “It reordered me, it redirected my sight, it changed something about the way I witnessed and participated in the rest of the world.” I think that's what I was really trying to press on with all this beating up of poetry, but what is poetry going to do for your action? What is poetry going to do for how you relate to the rest of the world? To offer my own counterpoint in the writing to all that anti-poeticas, I think I want to just read the end of what is the only true ars poetica in the book, which maybe is in counterpoint to all the tornado-ness that Evie's pointing to. This is from the end of ars poetica: “dear reader, whenever you are reading this is the future to me, which means tomorrow is still coming, which means today still lives, which means there is still time for beautiful, urgent change, which means there is still time to make more alive, which means there is still poetry.” I think when I put my revolutionary and human hopes for a free Palestine, for a world where people are housed and not hungry, where that is not a requirement that we place upon the citizens of the world, when I think about anti-war movements, about humanist movement, all these things, it's all about the volta. I always come back to that; the sense that something can open up, can transform, can redirect. I think I was maybe searching for, “Okay, poetry, beloved genre of my life, and also what pays my bills, can I track then how I see it transforming me or not? What can I put it in concert with?” I think this is a book that, by the end of it, still believes and loves poetry, but also recognizes that poetry must be in coalition with a great many other actions in our life. That the poet, at least the type of poet I want to be, cannot be satisfied by writing it down. But we have to live the stanzas as well and encourage others to get out there. There's a lot of wrestling here. Not just in poetry. There's as much bending towards the utility of violence and of retaliation here as there is hope for peace. I think the poem “end of guns” is right next to a poem about the apocalypse. [laughs] Like, how long could you go until you have to kill some white dude? [laughter] There's all this both-and. I want myself and to encourage the people who are going to pick this up to embrace that nuance. Because there's always-I forget who said that originally but, “There's the truth, and there's what really happened.” [laughter] One person's truth, another person's truth, what really happens is in between. So I want us to seek those nuances. I think there are too many clean answers maybe in some of my other books. I think I also always came off scot-free in those books. I just get to live and mourn and things happen to me. But I wanted to have more skin in the game and look at the blood on my own hands and think about my own complacency in things and the ways I've done harm as well. I think what comes out of that is something that's not trying to be pure or what is trying to be human. Humans wrestle, we struggle, we are not infallible. We are in fact very fallible, but that doesn't mean that we are sullied. We can learn from that dirt, we can learn from that wreckage, and I do think that there are things in us that must fall. So I'm glad for the metaphor of the tornado. There are things that I do want to destroy within my own thinking, that I have to kill the colonizer and the state in the easy ways that we fall into performing those logics. I have to destroy those. But in destroying that, the tornado is a great metaphor because I don't want to destroy my orientation towards love in that process. Poetry does teach me a lot about love so how can I be particular—I like that particular over precise—how can I be particular about what I do seek to destroy in the world and in the self? Maybe if that does nick my love practice or nick my faith a little bit, maybe that's a good thing. Maybe there are formulations on love and faith of mine that need to go away. That if I am trying to plow a path and destroy my relationship to the most vile parts of Americanness, then maybe there is something about the way Americanness has taught me to love that also needs to be scarred and then healed over in the process.

DN: Well, I really love Evie's notion of the tornado and of moving the cow to the other side of the river with us as the cows, I think, still alive, but in a new place, thanks to you, that you aren't just revising yourself, but you're revising us in the process. This image of a transported cow, I think it answers some of the questions you have about what poetry can do. Maybe as you say, no poem can free us, but it can still get us to the other side of the river. I'm thinking about the throughline in a lot of the questions we have for you, given that both Ama and Evie bring up the visual elements in your new work, the black box in “on knowledge” that your words page to page have a shifting relationship to, and the black line in the poem “rondo” that is the freeway that split your historically Black neighborhood in Minneapolis, where one in eight Black residents were displaced. I think about how you say the poetry can't just be what's written down on the page. Here we have not just white space, but black boxes and black lines. But I wanted to ask you about—or we have a question for you, and I'm going to piggyback on this question—I want to ask you about another element that takes us away from what's written on the page two. When I talked to Isabella Hammad recently, the episode you're in the middle of listening to, which is also about voltas, about turning points and epiphanies, there's a line that she says in that book, Recognizing the Stranger about writing against the consoling fictions of static identity.

DS: Whoo!

DN: Which I feel like that describes this book Bluff by you and your work, I think at large too, not just against static identity of a person, but even I think the static identity of the book itself as there's this QR code in the book that takes us away from the physical book entirely and to a very unfixed set of poems elsewhere. I'm going to play you a question that's particular about that. But I'm also hoping you'll in addition speak more generally about the QR code and what we would find elsewhere that's also somehow mysteriously tethered to the written in front of us. Until recently, Tin House's assistant publicist was the poet and performance artist Jae Nichelle. I had vertigo when I discovered who she was, [laughter] that one of her poems on YouTube Friends with Benefits has been viewed 1.9 million times, that she was huge, and really it felt like I should have been working on her behalf, not the other way around. Jae is, like you, a poetry slam champion, and her debut full-length poetry collection, God Themselves came out last year. So here's a question for you from Jae Nichelle.

Jae Nichelle: Hey, Danez, it's Jae Nichelle and I so appreciate Bluff through and through for sure and the QR code section of the poems makes me think about how that set of poems lives differently than the print book because theoretically, you could change those poems at any time, theoretically, since they exist digitally. There are several times in Bluff where you reference poems that you've written in previous books and how you'd address those subjects differently now so I'm wondering if you had the ability to subtly tweak poems in your books without anyone knowing, kind of like how people said Beyonce was regularly changing the Renaissance album on streaming platforms like lowkey. Would you do it? If not, why wouldn't you do it?

DS: Thanks, Jae. Jae is so brilliant. God Themselves was so brilliant. The chapbook that they released with YesYes is so brilliant. I just love that poet. Jae, I saw your Furious Flower and I don't think we got to talk long enough. I hope next time we get to sit down a little bit longer. Okay. No, I wouldn't change them. I think it's fine that they have the things that I disagree with. It's that thing about being in community with yourself across time. Do I wish that I could go back and whisper in my 14-year-old self's ear, “Hey, just do 20 sit-ups a day, you’ll appreciate it later”? Maybe. [laughs] Is there a part of me that wishes I could go back and talk to 23, 24 Danez and say, “This is a very good time to believe in condoms, young man”? Maybe. It would have saved me some grief and some health care, but I can't change the past, and I need those relics, not those relics, I need the things in the past that I wrote to still be true to who wrote them. If I were to change anything, it wouldn't be to revise the thought, it may be to change the line like, “Ooh, I think that's a little bit embarrassing.” There are a couple of poems out there where I was like, “Oh, girl, there's a better metaphor.” [laughter] Or “Just make the sentence a little bit more athletic.” It may be more for aesthetic reasons of just like I think there's a better way to say it, or I think there's a word missing there, or I think there was a better word choice. But I think the poems themselves, or the thoughts themselves that the poems carry, I think must remain true. Then, just like with Bluff, I had the ability to go back and reflect, to argue with myself to correct. I think that's what makes, let me get in my little Christian bag, that's what makes testimony so powerful. I call myself a Christian plus, I go to church still. I believe in a lot of other things. I maintain an altar for ancestor veneration. The God I believe in would not create only one door to the knowledge of him. I think there are many doors to understanding God. But the most powerful testimonies are the ones of transformation and of understanding. Job is maybe a little bit uninteresting when we think about Job himself from the Bible, or whatever your people call that text. We all got all the Abrahamic religions, we got the same first step. Job is so perfect that God and the devil want to test him. The story of Job actually I think reveals a lot more to us about God and the devil than it does about Job himself, who was just so perfect that he never cursed God. I think what's more interesting for me in my coming over religion was when people come up and say, “I was one way and then I changed my life. I used to believe this. I used to do this. I was out here in the streets bad and now look at me now,” that's inspiring. That's what's inspiring. It's not inspiring to hear somebody show up and say, “I was perfect always.” It's also really a violation to just the honesty of the experience of being human where people try to false flag like they've been perfect their whole lives. Oh my God, just went through some stuff with that in my family, went to a wedding where—they don't listen to poetry podcasts, I can say this—where somebody was just trying to pretend like they had been a perfect father their whole life and the rest of the family just had to turn to each other and say, “Well, that man were nowhere to be seen.” Why [inaudible] and so it's just like be honest, and we can be honest about our past selves. It's such a great offering to others to be able to talk about the ways we changed. While I do believe we need to center the voices of Palestinians in the ongoing genocide that is happening in Palestine right now, some of the most powerful testimonies alongside those Palestinian stories are the testimonies of anti-Zionists who were Zionists. To say, “I was once this way and now I am another. I freed myself from the shackles of my old thinking. I have averted, I have redirected.” That shows us the great possibility of humanity. I'm just speaking from my one little corner. I don't want to get rid of the old things in my poems. I want to learn from their mistakes. If there's anything that I feel does more harm than good, then maybe I might take some of those out. Maybe there's a line or two here, maybe, maybe, maybe, but I also feel like I want to leave the work in a way that is flawed. I used to talk a lot about productive failure and feeling like failure is this useful concept. I'm always failing. The poems are never perfect. We're always just sort of attempting to get as close to the hem of the garment as we can. I still think that's true. I think as writers, the process is not to make some perfect thing, you know? The most perfect book you can think of, somebody gave two stars on Goodreads. It also depends on who's looking, who is it going to be perfect for? Can I accept it for its fallacies and learn from it? I have dissatisfactions with every book I've written. Whether it be a particular poem that I just don't think is up to snuff by the time it comes to publication or maybe something about the process, but those failures make every book that comes after stronger with its own complications. I think Don't Call Us Dead maybe in my mind is like, “Ooh, I really wrote the shit out of that book.” Once I get rid of the shame I have towards Homie, not the shame, but rather the residue of what was not always a smooth process for writing that book, then I'm able to see the ways in which I'm like, “Okay, Homie, actually, there are some things that are really going on in there that are really cool that maybe are improvements that are doing some other work in the heart and in the craft of the thing that are really freaking cool, man. Similarly, in Bluff, I think I would say this is my best book so far, but there are things from here that I'm going to learn from as well that are already evidence of themselves in the work. I mean, we often use this metaphor about our poems or our books are children. It's just like the unconditional love. You got to love your baby, even if they're a little bit ugly. [laughter]

DN: To extend what you mentioned earlier about how Angel Nafis pulled you aside at one point to say, giving you a heart-to-heart saying, “Whoa, you should pull back on the self-critique,” an element that's still prominent in the book, which at one point, as you said, was way more. It makes me think of a line in one of her poems: Too much of a good thing is still too much. But what I think makes it work, perhaps similar to you move from he-ness to a plural they-ness or an “I” that was masculine to a “we” that doesn't map neatly on gender or race or nation, is that to interrogate the self for you, it seems to me, is to interrogate the culture and the nation that you were raised in. Not only the ways it has othered you or the ways it has wanted you dead, but also the other ways you, like all of us, reiterate it, repeating things that sustain it and legitimize it, which touches again on this issue of voltas within the self. I doubt it is a coincidence that there are both multiple anti-poetica poems and also multiple ars America poems in this book, and that an example of each opens the book together before the epigraphs of the book, two doorways that are kind of one doorway. It feels like Bluff in your self-critique becomes a decidedly anti-national book that emphatically decouples any "we" in your writing from anything to do with the US as a nation or with nations more generally. But before we explore it, I was hoping we could hear a couple of poems in that spirit, “ars america (in the hold),” and Last Black American Poem.

DS: Yes, yes. My pleasure. This poem particularly, I think I want to shout out Phillip B. Williams as a thinker. Yeah, I think it's in conversation with a poem of his and that takes a graphic of the middle passage of a boat of a slave ship and tries to talk about that. I think this poem here has loosely, in my head, shaped like that boat in the whole. Also shout out to Christina Sharpe, whose wake work from In the Wake and just much of her scholarship, I think has a great impression on my mind in the poetry.

DN: Yeah, me too.

DS: Yeah.

[Danez Smith reads from their latest book, Bluff]

DS: All right. This one, Last Black American Poem.

[Danez Smith reads from their latest book, Bluff]

DN: We’ve been listening to Danez Smith read from Bluff. I mean, all of this is up right now, again, with the genocide in Palestine and Kamala's candidacy. I was hoping we could talk about these poems, which critique past poems of yours with the ending line, "Forgive me, I wrote odes to presidents." But in doing so, also really critiques the tethering both of your story and the larger story of Black liberation to a national story, like I think about Roger Reeves, his critique of the centering of the Black experience as central to nation building in the 1619 Project, that for him, it is important to stay at the margins of the story of nation, to find true encounter and develop mutual aid in the margins, to not tell the story of a people that says, “Now it is our turn to be at the center,” or to say to native folks, “If you're upset that you aren't also focused on in our project, you can do your own project and center yourselves similarly.” But instead to tell a story of Black native alliance at the margins as he does with the story of Sixo from Toni Morrison's Beloved. We talked quite a bit about this when he was on the show, and I got the sense, though he didn't say it explicitly, that this isn't easy work, this critique, that it comes with blowback from his own people upset because of it, that it creates community and community across difference, but it also strains community. I think of Elaine Castillo's line, “Sometimes to fight for your family is to fight with your family.” But independent of Roger and Elaine, I'd love to hear about your engagement with this question of the story of self, the story of nation, which you're decidedly reevaluating in Bluff.

DS: I understand the great hope to finally be American, to finally gain back the two-fifths of citizenship that we were often do not. I understand it, you have no other motherland besides a story of interruption and enslavement that the furthest you can trace back is the water, which makes you want to be from here. I understand what it means to see Black people in positions of power and to feel like you have finally made it. But I question always what power does and why is power useful. If we understand the danger of that power, that particular American power, and how it exercises itself both within and outside of the borders of this country, I think it doesn't take thinking too long to come to the conclusion that maybe that power ain't worth it. Yeah, I am 100% with Roger. I have a poem in the 1619 Project, I didn't agree with a lot of the conversation that went on around that book. It was very hard to witness the dismissal of Indigenous critiques. I thought Natalie Diaz had a lot of fair points around that and just to be silenced. Why are we trying to center ourselves and we should be in solidarity--I agree we should be in solidarity at those margins. We should understand that there are, if we think about Black and Indigenous solidarity, those are the two original sins of this country. May we not try to wash those sins away in a way that allows us to come into power. I think, yeah, the first Black president is cool, but if he's not radical, what does that do? If Tim Walz becomes the first male vice president, not first male vice president, [laughter] but if he becomes the vice president, we will have the first Indigenous governor here in Minnesota when the lieutenant governor picks a position. What does that do? Is the land going to go back to its original stewards? No, we're still going to be the colonized state of Minnesota on Ojibwe and Dakota and other lands. I was just watching The Daily Show interview with Ta-Nehisi Coates.

DN: I was watching that too.

DS: Yeah. Jon Stewart was pulling that line from his new book, "your oppression will not save you." Similarly, becoming the partner of your oppressor will not save you, or becoming the oppressor will not save you. I think we really need to question why we aspire for higher positions and acquiescence in the colonial project. Surely, I'm questioning the idea of nationhood in general. I don't think nations do good things. But there's a village, a big village that we all live in called Earth. I think thinking about our solidarities within there that actually are more Indigenous in their practices that are one with nature and with each other and with the other creatures and the land is how we get there because we know that nations see both people and land and nature as resources and that are finite and often expendable for a very ephemeral dream. The American dream doesn't care, I think, about the next lifetime. It is so based in meritocracy and the individual that we oftentimes even start exploiting and doing such horrendous damage to the people that even at our most selfish we should still care about; our family, our community. Yet look at how it makes us betray love, look at how it makes us betray common sense for a nation so based in white supremacy, white supremacy which is so based in a historical and future relationship to purity and power. They don't believe in climate change, so it’s just like, “What are you even going to rule? What is so powerful about what you're doing if there's nothing in 50 years?” I think we have to untie our relationship, slowly but surely. First, it's the Last Black American Poem maybe for me. Denouncing, maybe trying to uncouple my blackness from the dreams of American-ness. You see it in the lives of other writers. We see it in Amiri Baraka who first becomes Black and radical in his politics and then realized that the racial critique isn't enough and becomes anti-capitalist. There are layers and levels to this power. I was very moved by the movie Origin this last year which is based on Isabel Wilkerson's Caste.

DN: Oh, yeah.

DS: The Ava DuVernay film, which takes the book and also narrativizes what was going on in Isabel’s life, beautiful film, I saw it three times and then scheduled for a fourth in my living room sometime soon. But what Isabel does in that book to really show how Caste is an identity politics tied to capitalist and colonial desires is brilliant. It makes me weep the way the information in that movie is uncoupled. But there's always that first thing you have to scathe away. For me in this book, and I think most abundantly in my work, it is a relationship to blackness and blackness within America and globally anti-blackness. I think my book very much, or most of my collections I think very much are comfortable being viewed of as afro-pessimist texts, so accepting the inevitability of anti-blackness and death. But also I think there's an afro-optimist tune here too, which recognizes like, “Okay, there is a somewhere and a somehow within the future where I can center my blackness but that also links me to something that is Indigenous and human in everyone. How can I start to shed these things?” So much of the book is about getting rid of the “I”, how do I get rid of what I've been told is the individual aspiration for greatness that will keep me from a collective possibility of holding on to possibilities? It really feels like we're in dangerous times where we need to really decide are we so invested in holding on to power and letting power reign unfettered, unchecked in its current systems or are we going to make some very uncomfortable decisions and maybe add a couple years to the clock? Because the Earth is ready to get rid of our asses. We're doing a very good job of speeding along both the ecological apocalypse coming and we look like we're very invested in killing each other too. Greed will exhaust us very soon. If and how are we going to break from the dreams of the industrial revolution and colonialism? We've gotten so far, we're so intelligent as a species. Yet, the great stupidity and ignorance of which we do damage to our world and to each other, when are we going to actualize all this intelligence that we got? We can make artificial intelligence now. We got computers thinking better than humans and it's ridiculous that we still can't recognize that the greatest gold we ever discovered was a language for love and the possibility of it and that it's real to I think most of us in all cultures and yet we still don't center it and actualize it. If the world had a love practice, war wouldn't exist and if our love practice was wide enough to look outside of the borders of language and nation, what could we achieve? But we're ignorant and we're greedy and we're scared. We let those things rule us. I don't know, I'm just trying to break some away because we gotta break some away. [laughter]