Diana Arterian : Agrippina the Younger & Smoke Drifts

As an artist, how does one dive into the wreck of an archive, a canon, a shared collective memory, a history—one filled with silenced voices, distorted accounts, erasures and elisions—on behalf of those wronged by it? Poet Dionne Brand says “the salvage is the life which exceeds the wreck” and Diana Arterian’s work seems animated by this work of salvage and recovery. We look at her new poetry collection, Agrippina the Younger, about a Roman Empress who, today, is only known as the “daughter of,” “sister of,” “mother of,” “wife of ” various men of history; and also at Diana’s new work of translation (co-translated with Marina Omar) Smoke Drifts, the first time the Anglophone world is able to engage deeply with the work of the Afghan poet Nadia Anjuman, a rising literary star silenced in the prime of her life. We look at feminist practices and strategies of archival confrontation in these two very different contexts, Ancient Rome and modern Afghanistan, and the different considerations and choices Diana makes as she dives deep into the wreck and somehow resurfaces to re-present these lives, this art, shimmering with life, for us.

For the bonus audio archive Diana contributes an epic medley of readings, everything from ancient Armenian poetry to some co-translations in-progress of contemporary Armenian poetry; from her memoir-in-progress to a hard-to-find 35 year old piece by Alice Notley called “Homer’s Art” which wonders how a women could write an epic and if “there might be recovered some sense of what the mind was like before Homer, before the world went haywire & women were denied participation in the design & making of it. Perhaps someone might discover that original mind inside herself right now, in these times.” To learn about how to subscribe to the bonus audio archive and about all the other potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter, head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today’s conversation.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today’s episode is brought to you by Heather Clark’s The Scrapbook. This debut novel from Clark is the story of an intense first love haunted by history and family memory. Inspired by the World War II scrapbook of Clark’s own grandfather, hidden in an attic until after his death. Writing in the Times Literary Supplement, Anna Katharina Schaffner called The Scrapbook “an ethical meditation on memory, complicity, and the psychological tremors that can affect our lives decades after the events that prompted them, events that we might not even have been alive to experience.” The Scrapbook is available now from Pantheon. For any listeners in New England, Clark will appear at the Brattleboro Literary Festival in Vermont on October 18th, a festival that will also feature past Between the Covers guests, Aria Aber. In a way that wasn’t planned or anticipated, this year might end up being characterized by, more than anything else, water. From the spring conversation with Patrycja Humienik about her book We Contain Landscapes to Rob Macaisa Colgate’s My Love is Water, from Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s Theory of Water to Robert Macfarlane’s Is a River Alive, from the time-and-space-defying notion of the sea within Madeleine Thien’s Book of Records—that is somehow an ocean, a building, a portal, a refuge, and more—to what will likely be the last conversation of the year, or perhaps the first one of next year, which is a deep dive into the science and poetry of water in South Asia and the United States, and a water-informed ethics and path forward. I only notice trends like this after the fact. But with four of the episodes this fall, I’ve recently recognized either the beginning of a new trend, or that they themselves form and complete an uncanny quartet of correspondences around the theme of diving into the wreck of the archive. Something we’ve definitely touched on before on the show, from Dionne Brand when we talked about her book Salvage, to Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s memoir of historical excavation, A Ghost in the Throat. This new quartet begins with the last episode with Olga Ravn and her book set during the 17th-century Danish witch trials, and how almost every word in the primary texts are the words of the men—the judges of these so-called witches—and about the remarkable way Olga finds to recover and re-present the women in this history, a methodology that is somatic and kinetic and utterly remarkable. Today’s conversation with Diana Arterian is the second of four that again is confronted with the erasure of women’s voices, this time both in ancient Rome and in contemporary Afghanistan, and a new set of strategies of how to enter the archive—to make art from the gaps, erasures, distortions, and elisions, to reveal the flimsy foundations of what is considered settled history, and more. For the Bonus Audio Archive, Diana has gifted us an epic contribution—a medley of readings, beginning with ancient Armenian poetry and then some of her co-translations in progress of a modern female Armenian poet. She reads as well from a memoir in progress and also from a hard-to-find piece by Alice Notley from a 35-year-old chapbook called Homer’s Art, where Notley asks, “How could or would a woman write an epic?” and wonders if, “There might be recovered some sense of what the mind was like before Homer, before the world went haywire and women were denied participation in the design and making of it. Perhaps someone might discover that original mind inside herself right now in these times.” These questions and wonderings of Notley’s are kindred questions to the ones that animate Diana’s work and today’s conversation. We get to witness Diana today showing us many possibilities of how to make this question of recovery into art that is vital and alive now. The Bonus Audio Archive and Diana’s contribution is only one of many possible gifts and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. Regardless of what you choose, you will receive the resource email with each and every episode, with everything I discovered while preparing for it—of the things either one of us referenced during the conversation, and places to go once you’re done listening. You can check it all out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today’s conversation with Diana Arterian.

[Intro]

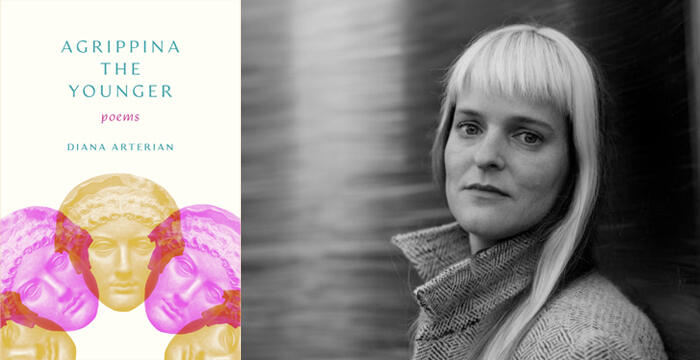

David Naimon: Good morning, and welcome to Between the Covers. I’m David Naimon, your host. Today’s guest, the poet, translator, critic, and editor Diana Arterian, earned an MFA in poetry from CalArts and a PhD in literature and creative writing at the University of Southern California. She has taught at CalArts, Fordham, Merrimack, and Wichita State. Her criticism has appeared everywhere from the Los Angeles Review of Books to the New York Times Book Review, and she writes The Annotated Nightstand column for Lit Hub, where a writer shares their TBR pile—or stack of to-be-read books—followed by Diana’s commentary on the titles. A column that has included the to-be-read piles of many past Between the Covers guests, including Rachel Zucker, Aria Aber, Danielle Dutton, Isabella Hammad, Brandon Shimoda, and Catherine Lacey. Arterian is also a long-standing poetry editor at Noemi Press and is the co-editor of the book Among Margins: Critical & Lyrical Writing on Aesthetics, where writers from Kazim Ali to Brenda Hillman, Bhanu Kapil to Alice Notley explore a different aspect of aesthetics. She’s a two-time finalist for the National Poetry Series, and her own writing has been recognized by fellowships from everyone from Millay Arts to Yaddo. Arterian is the author of two chapbooks—Death Centos, a collection of cento poems created out of the last words of historical figures that was picked as one of the best books of 2013 by The Volta, and also With Lightness & Darkness and Other Brief Pieces from Essay Press. Her first full-length collection, Playing Monster :: Seiche, came out in 2017 and was a Poetry Foundation staff pick and garnered a Publishers Weekly starred review, which declared that “Arterian weaves a family narrative of devastating clarity from letters, found text, memories, and more in her striking debut. At the core of the text lies the shadow of terror and abuse inflicted by a narcissistic and sociopathic patriarch. The post-traumatic stress of a family is a complex subject that Arterian skillfully describes in plain language, achieving deep emotionality.” Alice Notley adds, “Playing Monster :: Seiche is a devastating classic. It’s like reading a detective story or thriller, but with real pain, real consequences. Poetry exists against terror, Aristotle said, and the community is the audience for what one endures as it seeps out into us, the chorus. For we’re all the same one, aren’t we?” Now, eight years later, 2025 welcomes the arrival of two books of Arterian’s. This fall, we will see the arrival of Smoke Drifts, selections from both of the poetry collections of the Afghan poet Nadia Anjuman, brought into English from Persian for the first time ever by Diana and her co-translator Marina Omar. Persian translator Elizabeth T. Gray Jr. says of Smoke Drifts, “Anjuman’s biography is so iconic, so tragic, that it tends to distract us from the depth and brilliance of her work. Here is a poet who had mastered Persian’s classical and modern poetics, its forms, imagery, tropes, rhythms, and historical resonances. In these ghazals and free verse poems we find the patient stone, the caged bird, the green garden of hope blighted, the desire for a Beloved denied, all reworked in the context of twenty-first century Afghanistan. With passion, irony, and anger she distills that literary heritage, and the beauty and constraints of her life, into poems of ferocious and devastating precision. A voice with power to be reckoned with, and thus silenced in her time.” Already arrived earlier this year—and the reason for us gathering today—is Diana’s second poetry collection. This one from Northwestern University Press’s Curbstone imprint, entitled Agrippina the Younger. Past Between the Covers guest Diana Khoi Nguyen says of this book, “In Arterian’s vision, women have ferocious agency. This is the reclamation of a woman overlooked, alongside documentation of the author’s own obsessive searching for Agrippina, which is itself a mirror portrait of a contemporary woman reaching across centuries. This feminist collection is both a timeline and a map.” Robin Coste Lewis adds, “Diana Arterian was my classmate. She was a year above me, rightly so. Whenever she spoke, my understanding expanded. I grew. My mind unlocked. I began to comprehend the world and art more intimately. With Agrippina the Younger, with both its elegance and courage to embrace the history of our darkness—and with such aesthetic muscularity—I am learning from her still. By stepping toward, instead of running from, the ancient histories of women-hatred, Arterian somehow excavates these legacies with a language and lyricism that holds our horror and beauty in sublime balance. 'She does not look away . . .” Welcome to Between the Covers, Diana Arterian.

Diana Arterian: Oh my gosh, David. Thank you so much. Before we jump in, I briefly want to just reflect this brilliant light you always shine on your guests at the beginning and say that no one comes close to the work that you do, which is so rigorous and thoughtful and in-depth. I think one of my favorite things is listening to episodes where people have never listened before and they hear their introduction and are gobsmacked. But I think one of the things that really makes you remarkable is how much you care about the shape of the show and how you want it to change and how you're interested in maintaining an ethics. I am just so amazed with your work and so grateful. So I wanted to say this before you took me on the Jungian ego trip we're about to go on, [laughter] but also to make a plea to the listener that if you have 10 bucks or 20 bucks, please give it to this amazing literary citizen. I know that this is a passion project for you. You barely stay in the black. Anything that you can give, listener, please do. As soon as I got a job, I started to be a supporter, and I'm so glad to be here as a guest.

DN: Oh, Diana, this is going to be a love fest of debating because this is what I’m going to say in response to this.

DA: I was going to say your question better be good or else it’ll be awkward. [laughter]

DN: Because I look back, and it was seven years ago now that we first started talking about you being a guest on the show. Between now and then, you’ve been sort of a literary matchmaker. It’s because of you that Diana Khoi Nguyen reached out to me and that Douglas Kearney came on the show, and that another guest this fall is coming on the show too, who I won’t mention. You’ve also frequently included mentions of Between the Covers episodes in your Annotated Nightstand column at Lit Hub. The writer Ama Codjoe, I consider a guardian angel of the show. Long before she was a guest, she reached out as a listener and called me in, offering some advice around holding space as an interviewer, drawing from her past working with educators and administrators in arts and social justice. We’ve since become friends. I consider the way that you bring other writers together, both out in the world, but also how you continually celebrate the show as you do—

DA: It’s clear I’m a fan. [laughter]

DN: A different form of care, a form of guardianship perhaps. I wanted to start today also by saying thank you to you.

DA: Oh my gosh. I’m so excited to speak about this work and to speak with you.

DN: So the first two or three questions I’m going to ask are questions we are really going to be answering over and over again in different ways. So you don’t need to feel the pressure of being comprehensive, as I think by the end we will have been comprehensive. But as a very preliminary first step, orient us to who Agrippina the Younger is within the history of Rome, where this falls in that history. Before you begin, I’ll just add that it’s rare that a poetry book begins with a family tree, which I loved, but also appreciated having as its presence. I think its presence is a testament to this not being the easiest question of knowing where to begin and where to end.

DA: Yeah. It’s funny because in another interview that’s not out yet, somebody—it was Tiffany Troy—asked about the family tree. I realized that it was because of One Hundred Years of Solitude. I think it’s in One Hundred Years of Solitude where Márquez has the family tree at the beginning. Everybody has the same names. I was just referencing it all the time as I was reading it, like 20 years ago. Similarly, with ancient Roman families, everybody’s names are the same. Even siblings will have the same name. So Agrippina essentially was in what I think of as this golden family of Roman nobility. I think of them almost as the Kennedys. You know, her parents were this golden couple. They were in love. Her father was a general. He had incredible honors. Her mother and her father traveled together while he was on campaign, which was—I think she was the first noblewoman to do that—and actually had conversations with Agrippina’s father. His name is Germanicus. She would have conversations with Germanicus and have an impact on his campaigns. Her parents were ultimately connected to Julius Caesar and the other big names that you may know, even if you’re not super dialed into ancient Roman history. So I think one of the things that’s really interesting about her is that she’s born into this role that she’s going to get married as a teenager, which is really common. That’ll be a political marriage. She’ll have children, and those children ostensibly will fill some sort of political role—ideally sit in the imperial seat—but, you know, maybe there will be some jockeying or something. She came from a large family. She was one of six siblings, which was also really remarkable and kind of showered more positivity upon her parents. I think one of the things that’s really interesting about her family, which was something that I didn’t realize until after the book was done, was that it was the only time that there was a real sense of there being a dynasty in ancient Rome. You know, you have Augustus, who’s the high watermark as an emperor, but then his adoptive son or stepson, Tiberius, is emperor. Then we have Caligula, who’s Agrippina’s brother. Then we have Claudius, who’s Agrippina’s uncle, whom she also marries, which was also weird then. Then her son, Nero. So it’s all within the same family—five emperors in a row—which never happened again. I think that there was a lot of promise in all of this younger generation and all of them getting married and creating this long line of progeny that would continue this dynasty, which did not happen. Spoiler.

DN: When I look back to interviews of you from 10 years ago, back then you are talking about Agrippina the Younger and working on a book about her. Early in the book, you say, “I tried to chase the woman who built a secret entrance into the Senate so she could listen in on discussions otherwise reserved to men. A woman who described giving birth in the autobiographical form, usually used to depict military conquests.” These lines alone would justify an enduring interest in this figure, even as I think they only scratched the surface of what is compelling about her. But let’s chase not Agrippina for now, but the origin story of when and how your interest in her began, which is at least a decade old. When it began, how it began, and why it began. As I know, it began with a specific telling of her death and then ramified from there, I think.

DA: I wrote about this for Lit Hub, and it’s funny because I don’t remember the first instance of my connecting with her story. But one of the most famous points in her narrative is that her son, the Emperor Nero, had her assassinated. That, I think, is true. She died by his order. The version that I heard was that he had her cut open so that he could see the womb—her womb. I mean, he was fully tipped into madness at this point, I think. But this sense of “I want to see my origin, which created this incredible body and person,” it was so disturbing. I just could not get it out of my head. I think the fact that it overlaid the maternal body and violence so explicitly—I mean, almost to the point of being a farce or absurd. So I wrote what is actually the first poem in the book for a class. Everybody was just—and Robin Coste Lewis was in the class, Douglas Manuel, a lot of really amazing poets—they were all just like, “Who is this person?” I was like, “Oh, yeah, this is just one version of how she died.” So they invited me to write a bunch of poems about her death or the versions of her death, which include attempts at poison. Nero apparently—all the different ancient historians reference this—that he had a self-sinking ship built so that she would drown. That failed because she knew how to swim. So I became obsessed with that. Then I went to Vermont Studio Center, and Alice Notley was there, and I was already deeply obsessed with her work and was so thrilled to be able to even just sit in the same room as her. It was really beautiful because we ended up becoming friends in her time there. She looked at these original poems about Agrippina’s death. She was like, “Who is this person? What was in her childhood, essentially, that would provoke her desire for power?” I feel like she did this really beautiful thing of gently making me understand that I was doing the same thing that people had been doing for centuries, where they just focused on this dramatic, violent moment in this person’s life. Actually, I was just going through an old notebook to prepare for this conversation, and I found my original notes from that meeting with Alice, and I’m like, “Oh my God.” She was telling me the stuff to do that would take me eight years to figure out, where she’s like, “You should really look at these other books, and you should watch these operas about this family.” And then I was like, “Yeah, okay,” and then promptly, I guess, was so focused on just learning more about this person and her history that I forgot that instruction. But yeah, so that’s the origin, and then I just totally fell down the rabbit hole. Also, I should say it was quite late in edits for the book, pre-publication, that I learned that that version of her death—of having her womb opened—was a total invention quite late, from the medieval period, early Renaissance period, in these illuminated manuscripts. That seems to be this warping of what many people say were her final words, which were essentially, “Smite me here,” or, “Smite my womb,” or, “Strike here,” with the thought that she was hoping to strike the origin of her injury. “This is why I’m dying, it’s because of my son. The womb that made this child is why I’m dying, which I feel like is a really pretty remarkable and empowering final word.”

DN: In your defense, it seems pretty understandable that you would be fixated on the death and replicate this problem of historical memory, not only given this image of Nero cutting her open, but as you said, all these other death stories—the poisoning, the hitting over the head, the self-sinking ship.

DA: I mean, it’s absurd.

DN: Yeah, it’s hard to not be dazzled by all of these very melodramatic moments where lots of people are focusing not on what she accomplished, but either on her body or on her death, which you’ve written about. You’ve also written about the medieval illuminated manuscripts that some characterize as crass jokes at her expense, as they emphasize the sensuality of her corpse and also of Nero standing over this erotic corpse of his mother. Your book opens here with the end nevertheless, but then in an inverse chronology, the second poem is at the site of where she is born. This inversion of history and time, however, I think is from another vantage point true to the chronology of how you discovered her, and then moved from her death to her life. So I was hoping maybe we could hear these two opening poems, Agrippina the Younger—the poem of this false depiction of her death—and then The Rhine, where she eventually is born.

DA: Yeah, I would love that. Yeah, just to emphasize, this is the very first poem I wrote about her. It’s the spark that lit the fuse.

[Diana Arterian reads the poem called Agrippina the Younger]

[Diana Arterian reads the poem called The Rhine]

DN: We've been listening to Diana Arterian read from Agrippina the Younger. Let’s talk about diving into the wreck of the archive—spending a moment talking about the difficulties of doing so, which I think are many when it comes to the reclamation of women’s stories in particular. To begin, let’s set out the problems and obstacles before we talk about what your solutions are. As an entryway to provoke thought, even though these are different stories, I think of the fate of Sappho, an incredibly celebrated poet in her time—600 years before Agrippina—so celebrated then that Plato referred to her as the tenth muse. Yet we only have three or four complete poems of hers today. Mostly, we have fragments—single lines or fragments of lines. That is partly because some of these have been found within the rolls of papyrus that were mixed with plaster to wrap mummies, and others were recovered similarly as part of the stuffing of mummified crocodiles. Their fate is related to her fall in status, as this material used in mummification usually was discarded papyrus—like old government documents and other things that weren’t seen as useful or valuable, maybe if we’re wrapping something with newspaper today. This tenth muse, who had nine volumes of her poetry in the Library of Alexandria, many have suggested that her style and subject matter are part of why so little survives. A couple of centuries after her death, they’re already mocking her in plays as an immoral courtesan with a style of writing that was too simple and open, too personal, and too intimate compared to the typical public-facing hero narratives. Then with the arrival of Christianity, she’s called whore-ish and love-crazy, and her work is burned by the Bishop of Constantinople in 380 AD, another public burning by Pope Gregory VII in 1073, and then again in 1204. So no single collection of her work survives the Middle Ages, and almost all we have of her is the words of men about her—positive or negative—across the ages. I bring this up because Agrippina wrote three memoirs, none of which survive, and you have to wonder why they don’t survive, and just how accidental it is that nearly every written word about Agrippina, who assumes the throne of the empire of Rome, [laughs] is now a word written by a man. I was hoping you could flesh out the details and implications of this further for us regarding Agrippina—Agrippina the Great, political figure, and who knows, perhaps Agrippina the Great writer, who is also the wife of, mother of, daughter of, etc., instead of being centered in her own right.

DA: Thank you so much for that really nuanced history about Sappho, which I feel like synthesized so much. I recently read this book by Daisy Dunn called The Missing Thread that’s about ancient history and women. It really crystallized for me how remarkably rare it is to have anything written by a woman or even quoting a woman to endure from the ancient world. And, you know, the short answer for that is because of misogyny. I think it’s really interesting to hear about Sappho, who was so remarkably venerated, undeniably had her laurels as a creative writer, maker, and yet as time went on and society shifted and there were these big changes, her gender essentially was a reason to write her off. With Agrippina, I think just like any woman who is trying to write or make or be quoted, in general, they weren’t really felt to be worth the vellum or the papyrus or the parchment. The fact that she wrote those memoirs—so two of them were, and I’m sorry for not being able to quote the Latin—two of them were the misfortunes of her two families. So it was her mother’s family and her father’s family. Then she wrote the equivalent of a memoir, as you mentioned earlier, that normal women did not write. The people who wrote them were politicians of note, high-ranking military officials. It was just like a victory lap, basically. So the fact that she even wrote anything gives us insight into her as a person because she felt that her life and the lives of her parents’ families were worthy of record, and also that she likely had an interest in maintaining some sort of legacy. Yeah, Mary Beard—who’s the fairy godmother of this book, if you don’t know her work, you should, she’s amazing—she’s the one who says, and I quote her, she says something like, “It’s one of the greatest tragedies of classic literature that we don’t have these works, even any of them.” And then the fact that, and I reference it multiple times in the book, how the reason we even know they exist—well, I guess Tacitus in his Annals had access to them. It was before they were destroyed. So he ostensibly references them, but he’s also a very hostile narrator toward Agrippina and her family. But the reason that we even know that she wrote these books is because she talks about giving birth to Nero and him being breech, which is deadly today, and how they both survived. Pliny references it in his Natural Histories under prodigious and monstrous births. But he doesn’t quote her. So it’s like, it’s so terrible, because you can feel the proximity is so palpable, but it’s still gone, you know.

DN: It feels important to say, because I think the natural tendency is to think that these things have been lost to time accidentally. Even in my conversations with Ursula Le Guin for the show, she was talking about this in sci-fi even now. Someone who was getting as many awards and was as much a part of the conversation in the 80s as William Gibson was with Neuromancer, where they’re big and comparable peers. We still know 25, 30, 40 years later of William Gibson, but we don’t know of this other person. It’s like they quietly slide out of—or don’t enter—the canon. She was worried when we were talking about what is going to happen to Grace Paley, for instance. That was someone she was focused on, like, “Is she going to silently fade into the background?” A lot of what she talked about, which I think you do, is feminist citational practice against oblivion. Like you mentioned, this lineage with Alice Notley. You’ve also written about Carmen Giménez and the things that she’s helped you with in terms of editing. Later, I want to talk about the ways you address the absence of what we have from Agrippina herself by using prototypical Agrippina figures within history as well. But I just wanted to acknowledge that it feels like this is still a contemporary question.

DA: Oh, yeah. I think it’s also important to note that her existence in the archive, even though her words—she wrote all these words and they didn’t survive—that was a decision that people made to not allow them to survive. She represents innumerable women and people who, for whatever reason, are chewed up by systems of power to not exist in the archive. I know about her because she’s an empress. You know, she was this incredibly powerful woman. There are endless, endless people who were just as worthy of attention, who didn’t have the opportunity for whatever reason—pointedly, because in general, the archive is a violent, colonial, hegemonic practice and system. What you were saying made me think of when I was at the residency at Millay Arts. Edna St. Vincent Millay was a rock star. She was the first rock star American writer. It’s really surprising to me. Ostensibly in the canon, she’s still taught in schools, etc. But her home is in disrepair. We can’t access it really anymore, except for really random events. So it’s not that long ago. You know, I don’t know—100 years ago. It’s just really stunning where we’re throwing our attention and efforts for preservation.

DN: Well, in listening to history podcasts about Agrippina, it’s interesting that as Rome moves from being a republic to an empire, women end up having more power and influence. She, as you said, comes from Rome’s first family. When her brother Caligula is the man, she has great visibility and status. She has box seats at the game. Later, she’s the first woman on a coin. She’s the first woman mentioned in a loyalty oath. But also all these other things, I think, that aren’t particular to her but are particular perhaps to the era. Her father dies under mysterious circumstances. Her mother is killed horribly. Her brother Caligula is assassinated. She marries the new emperor, Claudius—her uncle—who ultimately is assassinated by poison, of which Agrippina is accused. Given all that is happening around her by everyone else, it is certainly possible she did do this, but these historians on multiple podcasts also raise the point that this is also the trope of the times—the devious woman who poisons—that it should at least cause us to pause, if not, as some do, look upon it skeptically. This trope is made into a caricature by many elite male historians who repeat each other, as your epigraph from Tacitus nods to when he says, “I am not inventing marvels. What I have told and shall tell is the truth. Older men heard and recorded it.”

DA: I know. [laughter] It just stopped me in my tracks when I got to that.

DN: It’s so good. It’s so terrifying.

DA: Yeah.

DN: So really, it seems that even the broadest strokes of history, in its most general sense, might be or perhaps should be up for debate. Perhaps we confer into other things—for instance, while it’s understandable that Nero would rebel against his micromanaging and critical parent when he’s in charge, that he likely only killed his parent because she was a mother and not a father or an uncle. I don’t know if that sparks any more thoughts for you.

DA: Yeah. I mean, I think one thing that’s not ha-ha funny, but generally funny, is—of course, I have a Google alert for Agrippina the Younger, and I have had for years. Most of the times she pops up are in news articles about poisoning and mushrooms. [laughs] There was a recent murder attempt, I think, in Australia where somebody tried to use poison mushrooms. So she’s been popping up there. I’m trying to remember some of the other things that you said—I was trying to scribble things.

DN: Just the sexism in the trope, like on the one hand, you could say, as you do in one of your epigraphs, and it’s probably true that poisoning makes sense as a form of soft power influence for a woman who doesn’t have access to something structurally, yet it could be used against women who haven’t done anything at all.

DA: No, I think that there’s some statistic, a fuzzy statistic, about how actually probably the most murderous people are all the women who killed their husbands through poison over the years. Let’s hope that they were breaking free from oppression in that act. But I had this moment when the book was about to come out and I thought, “Oh, God, does this book even need to exist?” Obviously, people know at this point that she’s not reduced to potentially poisoning Claudius. I don’t know if she did. Probably not. I mean, he was 63 at a time when living that long was pretty remarkable. He also could eat and drink whatever he wanted, which he did constantly. But then I got in my Google alert on Agrippina the Younger that there was an event for an illustrious nationwide institution that was going to talk about her. So, of course, I hawked the 13 bucks and watched and was absolutely gobsmacked by the fact that this guy, who was a scholar of ancient history, was just saying the same stuff about her. “Oh yeah, maybe she had sex with Nero, and maybe she had affairs with her brother”—just stuff that was like any modern historian today would say was not true. “Oh yeah, maybe she killed all these people. Maybe she killed her second husband.” You know, I think in general, coming out the other side of ten years of being in those texts is that it’s really hard to say what’s true, and we’ll never know. At the same time, I think it was absolutely a time of drama and political intrigue, and people were being exiled, assassinated, forced to suicide pretty consistently. I think in large part because they were in a relatively new political system where there is one person with a lot of power, where previously there had been a Senate, right? So a group of people who would make decisions. But if it is all pointed onto one person, there’s suddenly a lot more room for paranoia and fear. But it’s also the space in which women were able to have proximity to remarkable amounts of power, like Livia—her grandmother, Agrippina’s grandmother—and employ that proximity with remarkable facility. So yeah, I mean, I think it’s pretty stunning to me how it continues and how she’s just like this footnote as somebody who, “Oh yeah, she just had sex with the wrong people and murdered her husband probably and got murdered herself. The end.” [laughs]

DN: I would love for you to read The Death of the Emperor Claudius at Age Sixty-Three [in Its Multitudinous Truths].

DA: Yeah.

DN: But before you do, or as a preface to doing so, talk to us about the long titles—titles like Caligula Starts with the Forced Suicide of His Adoptive Son [with Whom He Was Named the Share Power], or The Exile of Agrippina’s Mother by the Emperor Tiberius for Four Years [Until She Dies Where Her Mother Died and a Daughter Will].

DA: Right. [laughs] This is a very, very fair question. It’s just a basic craft one in that a lot of times I found I was trying to shoehorn in context for these chronological markers into the actual lines of the poems. Then I just felt like it made them feel really wooden or dead. Or every time I would try to edit, they just felt like they didn’t belong there. I know that the book itself, in terms of the chronology of Agrippina’s life, is a little amorphous and soupy. But I wanted there to be enough things for people to hold on to so that they could have some context and so that they could understand this insane, insane period and what was happening. So this is The Death of Emperor Claudius at Age 63 and Its Multitudinous Truths.

[Diana Arterian reads the poem called The Death of Emperor Claudius at Age 63 and Its Multitudinous Truths]

DN: So the next question is one that has innumerable answers, because I think it’s the lifeblood of what makes this book unique. Anywhere we start will be necessarily incomplete to explore how you engage with the history and the positionality of yourself within it. But I knew for sure when I heard this next question that I wanted to start with it rather than one of my own, because it’s so incredibly well articulated. This is from the poet Brandon Som. His last book of poetry, Tripas, was a finalist for the National Book Award in Poetry and was the 2024 winner of the Pulitzer Prize. Rick Barot says of this collection, “In Brandon Som’s Tripas, a vision of the self is profoundly contingent on portraits of others that manifest ‘what’s passed down and what’s recovered. Saturated with exuberant language and story, the poems in Tripas have the amplitude of archives and the intimacy of songs.” So here’s a question for you from Brandon.

Brandon Som: Hi, Diana. This is Brandon Som. It’s a thrill to be a part of this conversation about your brilliant work. For my question, I was hoping you’d talk more about your approach to and understanding of the act of study that you invoke at the start of your book by quoting Solmaz Sharif, who writes, “History is a kind of study.” The educational model we are often given presents study as an act that is quiet, focused, and often passive—the rote memorization we do when we study for an exam. A study is often bookish, reserved, and respectful. To have a study is often a marker of class and class privilege. In your book, we encounter study as something far more active and dynamic. It involves movement, traveling across time and space, as well as form and genre to include prose and verse, as well as lyric poetry, travel writing, personal narrative, historical analysis, and literary and cultural criticism. Could you talk about the act and activism of study in your book and the experience of what it means for a poet to engage with history as a kind of study?

DA: Oh, my gosh, Brandon. Brandon and I also overlapped during our PhD. I remember he did a job talk to prepare for something. It’s all these faculty and then me and maybe one other student. As soon as he finished, we were supposed to give him feedback. I immediately was like, “I cannot wait to tell people that we went to school together and that you were an absolute genius.” I knew it right away. [laughter] The faculty were like, “Okay, anyway, so here are some notes.” But I stand by that. He just has such a beautiful spirit and is so brilliant. His writing is astounding. I love this question. It’s something that I have been thinking about a lot. I think he does such a beautiful job of describing the different shapes that study can take. He and I also, because we got our PhDs together, there’s a certain kind of rigor that we’re taught that we are meant to employ, and that it should have a certain shape and level of intensity. I certainly brought a lot of that to this book, in that I felt I needed to read a whole lot because I’m not a historian. I don’t really know anything about ancient Roman history. What I do know is within this 100-year period, if anything. So for anyone out there who’s a deep lover of ancient Roman history, if I misspeak, please forgive me. But I think anything that takes a decade to write, you’re going to change. With every single—or nearly every single—line or image, there are pages and pages and pages of reading that I did to try to pin it down, or if I invented, to invent based on something that felt real. At the same time, the fact that my first point of contact with Agrippina was the half a dozen ways she died showed that ancient history wasn’t really something I could trust or lean on in the way that we’re often taught we can and should. So as I was writing and as I started to also integrate these prose poems, it feels like a lot of things exploded out more. I wanted it to be less about drilling down into something and having a really certain sense of an answer, and more groping in the dark and trying to just be open to whatever came. I recently did an event with the absolute powerhouse and former guest, Anna Moschovakis, and she talked about it as a feminist epistemology, of how there’s almost this kind of searching quality to it, that it’s broad and just kind of open and curious. That was certainly how it ended up for me, how it felt. Even though I did these self-made assignments where I would read certain things or watch certain things or go to Rome, what I ended up wanting to include was also that experience of just feeling lost and not knowing what to trust or how to try to describe something.

DN: I love Brandon’s framing of your study as kinetic. One of the most notable things about the book is that your active contemporary pursuit of Agrippina is a big part of the book. Your previous collection, Playing Monster :: Seiche, which also has an archival element with found texts and letters, began as two books—one about your childhood experiences with an abusive father, and later as an adult, the aggressive, sometimes stalker-like acts toward your mother by strange men; the other book about a body of water and the pollutants that it becomes the receptacle for—an ecotext of sorts that you improbably, if successfully, worked these two books into one book. So it’s interesting that the Lit Hub review of your new book says, "Agrippina the Younger can sometimes read like two projects in one, each good enough to be published solo: the Agrippina poems add up to a verse biopic, lean and lived-in; the prose poems, a travelogue featuring Arterian herself as tour guide, armchair art historian, and immaculate endnoter. But the book’s sparks fly in the flinty friction between the two projects, between verse and prose." So we have a question for you from another who shares my desire for you to talk further about this double project held together as one—that is, if you even see it this way at all. This is from past Between the Covers guest, the poet and artist Mary-Kim Arnold, who works with both text and textile as mediums and who came on the show to talk about her book The Fish & The Dove, which, like your book, is engaging with the archive and archive formation and the reclamation of female voices within it. Both her personal history engaging with transnational adoption, but also the history of occupation and war in Korea, and much more. As Diana Khoi Nguyen attests to when she says, “At the core of this collection is the legendary Semiramis who, born from an Assyrian goddess, married an Assyrian king, ruling his empire after his death in a time when a female ruler was unthinkable. Through persona and self-portraiture, as well as found language, Arnold has masterfully crafted a searing account of personal history unflinchingly situated within fraught contexts.” So here’s a question for you from Mary-Kim.

Mary-Kim Arnold: Hi, Diana. This is Mary-Kim Arnold. I’m delighted to be able to ask you a question about this beautiful book. I loved the decision to include the family tree, which put me in mind of some particular kinds of texts, like a multi-generational biography or maybe what we might think of as a more traditional history book. The titles themselves of each section are primarily descriptive of particular events or places. Of course, when we see the alternating poems and prose passages, we understand that we’re in a very, very different kind of book. I guess I would just love to hear more about how you thought about the alternating poems and more narrative passages working together as the book was coming together. Thank you so much.

DA: Well, it’s so great. I’m such an ardent fan of Mary-Kim’s work and so grateful that she blurbed this one. You know, it’s funny because I think that, as you so aptly pointed out, both of my poetry books at the very least jockey between two narratives—or in the case of this, it’s that, but also very different modes. Part of me wonders if I just watched too many soap operas as a child. [laughter] I mean, because I think that it’s not even a question of attention, but I think in general I really love how things can vibrate, even if they feel like they’re very different from one another, or how they can illuminate more. You know, with my first book, there were these two stories that didn’t feel connected to me at all at first. Then it was so clear that once they were put together, they illustrated something much bigger than just what happens in the walls of the house. I think that part of it too, maybe to extrapolate a bit on what the poem titles were doing, I think having these prose poems, hybrid pieces, also allowed for me to expound more on some of the context and also how I felt about it. I’m in some of the more ragged, right-edge poems. But yeah, I just felt like it gave me a level of freedom. Also, at least to me—I mean, I’m impressed that Lit Hub thinks that the book could also just be the spare poems—but I feel like it would get really... I mean, they’re really intense. It almost feels like there are these two different shapes. There’s this laser that’s being pointed or something in the more “normal” poems. Then the prose poems are almost like this mist or something where it’s like you can move between. It provides a reprieve, at least for me as a reader. But also, I wonder if there’s some deeper thing that I should work on with my therapist about how I don’t have a lot of faith in just being able to pursue one thing and how that will deliver or work. But I think a lot of it was just, perhaps pointing back to Brandon’s question, the whole process was so intense. I was really just feeling along and trying to think of alternatives. I tried to pursue what shapes the work required and tried to heed those. One of the ways that I did that, which I talked about in my interview with Diana Khoi Nguyen at BOMB, was Bhanu Kapil’s Humanimal was an absolute touchstone for me for writing this book, and how she includes herself. There are lots of different—I mean, she goes even into more exciting media using images—but how, you know, moving through time, thinking about people who were real, also going to the place where these girls—for those of you who don’t know it, there were feral children who were taken from their wolf family. This is all real. An Indian missionary killed the wolves and tried to "domesticate" them. They both died relatively quickly. But Kapil wrote this book because she wanted to write her MFA thesis and just pulled a book from a shelf. It was this man’s diary. So there’s a lot of overlap in her interests. You know, it’s like here are people who were misused, to put it mildly, and who were real. You can go see where they lived. But also, she’s connecting it with more personal experiences and kind of putting herself in their story. But yeah, I don’t know. I think there’s something that makes it a little spicy. [laughs] People say it’s a page turner. People have said both of those books are page turners.

DN: They have, yeah. I love all of Bhanu’s books, actually. I don’t think she has a bad book, but I think Humanimal might be my favorite.

DA: Yeah, me too.

DN: But it’s another thing to just mention, I think, about it. This is another testimony of a man, a missionary who ran an orphanage, saying he rescued girls from wolves and killed the wolves. There are no witnesses. A lot of the objective stuff around it, including the photographs he provided and including the doctor who was there, contradict that the story is true at all. That there’s talk that he beat the girls to perform in certain ways, that one of them was neurodivergent. So there’s this whole question of, I think, also of rescuing the girls from the narrative of others. Because also in Bhanu’s book, there’s also this European film crew that’s filming theatrical productions of the mythology of the wolf girls, which is interesting that there are no words, again, there are no words other than the words of this book.

DA: Yeah. So one of the beautiful things about it is that she tries to invoke a haunting so that they can be present in some of the poems, but it terrifies her.

DN: That reminds me of when you were talking with Diana and BOMB, you talked a little bit about, or maybe she talked a little bit about how Romulus, who is where the name Rome comes from, is a twin who mythologically was raised by wolves. There’s all this imagery of them drinking wolf’s milk from their wolf mother, but that the word for wolf was also the word for whore, or came from the same root word?

DA: Yeah, lupa. That was Mary Beard. Drop that knowledge.

DN: Okay. So we have this other alternate story, perhaps, for how the namesake for Rome was raised.

DA: Yeah, by like a sex worker rather than a feral animal.

DN: Yeah.

DA: I mean, the fact that those are ostensibly social equivalents is notable.

DN: Yeah, I think so too. Well, I would love to hear an example of this other mode, the contemporary prose mode that I think is both somehow more active, to think back to Brandon’s notion of movement, but also more reflective at the same time. I was hoping we could hear The Colosseum.

DA: Yeah.

[Diana Arterian reads the poem called The Colosseum]

DN: We’ve been listening to Diana Arterian read from Agrippina the Younger. Well, one thing that you do that I really like that I mentioned earlier, that perhaps is another strategy to deal with active gendered erasure and/or silence within the archive, is to reach toward other female figures in Agrippina’s time and constellate them in some fashion with Agrippina. For instance, you call Messalina a counterpoint to Agrippina. Messalina, the wife of Claudius before Agrippina, who was characterized as sexually insatiable, predatory, and ruthless, where Tacitus, once again, and Suetonius, and also Greek historians who self-described as suspicious of women, are the ones spreading these stories and canonizing them after her death. She, like many then, is sentenced to death by forced suicide. But also, she suffers what is considered the worst punishment possible, worse than forced suicide, which is to be condemned to memory oblivion, which is interesting to think that lots of people aren’t officially condemned to memory oblivion who are suffering the worst punishment, memory oblivion. But in this case, where you’re removed from the historical record, from coins, statues of you are smashed, and more. You call Livia, the wife of Augustus and Agrippina’s great-grandmother, a woman of great influence and power, so much that the senators, fearful of her power, argued for a return to a republic from an empire. You call her a proto-Agrippina, and you even connect Agrippina with the Celtic tribal queen Boudica. In your poem with the amazingly long title, The Uprising of Over 200,000 Lead by Tribal Queen Boudica for Her Husband’s Naming His Two Daughters (and Nero) as Heirs When She Became a Widow]. In that poem, Boudica gathers her tribe’s people with her daughters in her chariot and kills between 70,000 and 80,000 Romans in the British Isles, with you saying on her behalf, “I’m fighting as a human for my stolen freedom, bruised body, enraged daughters. As for your men, go ahead and live and be slaves.” You say in your essay Power, Motherhood and Murder that Agrippina is power-hungry in a way that is usually coded as masculine, and perhaps that is why you call Agrippina Boudica’s shadow. Of course, I’d love to hear any thoughts you have about any of this, but mainly, I was hoping you would talk about Octavia and the anguish you felt when you ultimately removed a series of Octavia poems from the book. Enough anguish that you’ve written an entire essay about them and her. A woman you say "performed the role of Roman woman, a few words poised, demure, with such perfection, even the misogynist ancient historians love her. None of this was enough." You also say of her that she is a "young noblewoman chewed up by the system of Roman politics, totally innocent and dead at 22, despite playing by the rules," and "her abject disempowerment at the orders of a lunatic, all of which happened despite being an emperor’s child and part of a noble family." Talk to us about the removal of these poems and the importance of Octavia and of your poems to her, nonetheless.

DA: I so appreciate this question and the ability to shine a light on this woman. I mean, I think that maybe on opposite ends are Boudica and Octavia, right? Boudica, who righteously feels that she has the right to fight back against this colonial power, and does, I mean, remarkably, goes far, kills lots of people, raises London. Then Octavia, who is essentially playing her role, she’s doing her job. “Okay, I will marry whomever you want. I will do whatever you need.” Her marriage to Nero was really crucial for, again, thinking about the extension of that dynasty. “Okay, great. We’re braiding the Claudian and Julian lines. These two are going to get married. They’re going to have kids. We’re going to have emperors for generations.” Yes, I had more poems about her, including Nero is the first emperor to assassinate his brother, his stepbrother, Britannicus. This happens at a dinner, a public dinner. Octavia’s there. So she watches her brother die. Her father’s already dead. She doesn’t have anybody. She’s, I think, 19. I think her precarity and vulnerability are just so palpable. Of course, we know very little about her. I think we know even less than we do about Agrippina. But at the same time, when she’s thrown into exile by Nero, who claimed that she was barren and essentially did all he could to sully her name, including having an ally claim that they had had an affair, whatever. People took to the streets. They held up statues of her, and she clearly was beloved, probably because she played by the rules so well. She was part of this dynasty. It’s really heart-wrenching. The other person I think of, too, who I wasn’t really able to include is Sporus, who is a young man who looks so much like Nero’s second wife, Poppaea, who dies probably in childbirth, to the point where other people are like, "This is remarkable how much he looks like her." Nero has him castrated. They get married. He’s wearing an empress’s regalia. He’s called the empress and mistress, but he’s also tethered to this horrible person. After Nero dies, I think he marries another senator. He has this really difficult—I mean, he doesn’t have any agency at all. I think he ultimately dies by suicide. Very young, maybe 20. So there are these people who are just so vulnerable and don’t really know or don’t have the capacity for whatever reason, whether it’s because of how little power they have or they don’t have the political minds that some people do. I think Messalina is a good example in that she was somebody who I think did want power, but also didn’t really know how to operate within that system in a way that Agrippina did. Yeah, I mean, I’m still heartsick over it. It was 2,000 years ago. [laughs] I still really wish that she had had a different outcome. Who knows what kind of person she was, but nobody deserves the death that she had. So young and totally innocent.

DN: Well, I want to step outside of this book for a little bit, but I don’t think we’ll be really stepping outside of its themes. Within the book itself, you are also another person like Livia, like Messalina, like Boudica, put in relation to Agrippina. I don’t think it’s a stretch to see the themes you explore with your mother and your family in Playing Monster :: Seiche as having some resonances with questions of male power and the silencing of women’s voices within your latest collection. But I wanted to spend a little time with your other book out this year, the book you co-translated with Marina Omar of the Afghan poet Nadia Anjuman’s poetry, a book called Smoke Drifts, because it feels in conversation with your project with Agrippina too. Perhaps the most obvious way it is, is because it is yet another example, like the origin story of your interest in Agrippina, of a woman whose death and the circumstances of her death threaten to overshadow the brilliance of her life. Here is Between the Covers guest, the poet Aria Aber’s words from her introduction to Smoke Drifts: “Anjuman married a man who was, like her, a graduate of literature at Herat University, but rather than finding a true partner in him, he and his family denounced the publication of Flower of Smoke for having brought shame upon the family. On November 5, 2005, just a few months after the publication of her first book, her husband beat her unconscious and left her to die the most terrible death. According to Anjuman’s brother, beatings were not uncommon in their marriage, and although her death is often called an alleged ‘honor killing,’ in reality, this femicide was the consequence of a far more quotidian domestic violence, and her husband was arrested for her murder. Anjuman’s father was pressured to forgive him to lessen his sentence, to which he relented. This led to a quick release, and the husband was granted custody of their young son. In the end, there was no real justice for Anjuman’s heartbreaking death. The tragic end to her short life manifested her fate as a martyr and made her a symbol of all Afghan women yearning to be free. Despite the circumstances, I hope that it isn’t by her death that she will be defined, but rather by her poetry.” Here again, you’re part of a project, I think, to release someone from definition by others. I was hoping to hear a little more about Nadia’s brilliance, her poetry, and your engagement with it—an engagement that goes back 15 years.

DA: Yeah, it’s really interesting. I didn’t plan for these two books to come out the same year. It just happened that way. As I was editing the addendum to that book, Smoke Drifts, and then also looking at some of the materials I had written for essays about Agrippina, I realized that both of them, some of them, there was essentially the same first sentence of “I learned about this person because of her murder,” which is something that I’ve reflected on a lot. Part of that certainly is that that’s not how they deserve to be remembered. I think too, to kind of dip into something a little more personal, as I’ve been reflecting on it, I think—well, just for example, I remember when I was still in the thick of writing the Agrippina poems, and I was talking to one of my siblings. I was like, “I don’t know why I’m so obsessed with this person,” and my sibling just rolled their eyes, and I was like, “What?” and they were like, “It’s clearly about Mom.” I was a little taken aback, and I didn’t—I mean, now it seems obvious to me. I had a mother who I loved so deeply and I was totally obsessed with. And I think the reason that feels connected is that this was somebody who was in a really abusive relationship with my father who, for some context, his first wife left him when he put her head through a window, and his third wife left him after he broke her collarbone and tried to throw her down a set of stairs. A very angry, violent person. The fact that my mother was able to extricate herself and four children from an abusive situation like that is a statistical anomaly, and that nothing grievous happened to any of us. Especially for anybody who has children, those consistent points of contact—because they had, I mean, this is the ’90s—they’re barely bringing in issues of abuse into divorce proceedings. So any points of contact between an abuser and the victims, there’s more potential for violence to happen, right? It was something that she had terrible guilt over, that she had had four children with this person. It was something that I would really try to coach her through and explain, like, “No, you’re actually a fucking miracle. You got us all out. All.” But I think one of the things that has become clear to me as these two books are coming out and I’m thinking about them together—and these two women who are separated by 2,000 years but ultimately are dead because of male family members, very different circumstances—but this is the defining feature of their lives, according to history, right? Is that absolutely that could have been my mother’s outcome. Statistically, very likely. Or something terrible happened to me or one of my three siblings. I think the fact that that hasn’t changed for 2,000 years, and it doesn’t matter where you are in the world. I mean, I make a pointed note in my translator’s note in this book about gender violence. One of the facts that I learned recently that really blew my mind was the number one killer at the workplace for women is men, because that’s where they know where to find them. It’s often when they try to leave. That’s the United States. So anyway, I’m trying to remember what your question was. I’m sorry.

DN: We can stay with the translator’s note. I really appreciated the translator’s note because I feel like it humbly acknowledges the fraught positionality you have in relation to Nadia Anjuman—one with, I would imagine, many more potential pitfalls than your relationship with Agrippina. In it, you engage with your whiteness and your Americanness, the ruthless history of the U.S. occupation of Afghanistan, that you aren’t a speaker of Dari. You do, I think, a delicate and complicated tightrope walk around acknowledging the plight of women under Taliban rule while not making it a spectacle that a so-called civilized person would look at from afar. Where in Nadia’s time, in Aria Aber’s words, “She studied literature and writing in secret at the famous Golden Needle Sewing School under the guidance of the professor Muhammad Ali Rahyab. Three times a week, about 30 women in long burkas met up at his residence under the pretense of learning how to sew. But beneath the fabrics and needles in their bags, they carried books, pens, paper. They discussed Dostoevsky and Nabokov and Tolstoy while the children played outside in the courtyard. Those children would alert the adults in case the morality police came to check on them. If they had been caught, they would have been sentenced to death.” You mention that after the more recent re-takeover by the Taliban, where women now aren’t allowed to speak or sing in public, that women, unidentifiable in their burkas, are posting videos of themselves singing poems of resistance, including poems by Nadia. But you puncture our tendency to buttress our self-regard as the enlightened and civilized, similar, I think, to the way you do in Agrippina the Younger around modern portrayals of Caligula and his era as an utter freak show. You say that we portray it this way so that we can re-inscribe ourselves as not them. You do this in your translator’s note, citing statistics like the one that you just cited—for instance, that nearly half of all female murder victims in the U.S. are killed by an intimate partner. But mostly, I love how you talk about your collaboration with Marina Omar—that it was important that you were doing this work with another woman, that Omar was born in Afghanistan at the same time as Nadia, that she was a translator for refugees. And finally, at one point in the note, you say, “Anjuman’s work is a means of access to a particular voice that has been consistently forced silent by regime after regime, and then pigeonholed by Western media outlets and governments as nothing more than the voice of the oppressed in need of saving.” I want to hear some of your Nadia poems—some of the poems that you’ve translated of Nadia. But before you do, do you want to speak to any of this, to the poems themselves? What attracted you to her writing or to the collaboration with Marina? Anything about this project in that way?

DA: Yeah, as you mentioned, it started 15 years ago. So this year is a crazy culmination of a lot of years of effort. It was during my MFA. In one of my courses, there was a student who made some offhand comment about, “Why does poetry even matter?” Obviously, he was not a poet. I was just totally stunned. I was stunned silent. I didn’t know what to say. This was in a course discussion. But in classic Diana Arterian style, I immediately got really focused on how to create something to prove him wrong. Because I had met a poet while I was in college who was tortured over her poetry under Pinochet, not to mention the long history of poets who are considered incendiary or who can transmit information or commentary during fascist regimes or oppressive governments. So I was so angry. I started to make a chapbook, which I actually tried to find before this interview because I was thinking about it, but I think it’s in a box somewhere. That was called A Criminal Poet. I did all this research about these different poets who were incarcerated or killed by their governments—so like Lorca, Osip Mandelstam, Nazim Hikmet, who was a Turkish poet—just wanting to write about their lives and then wrote, honestly, some not very good poems about their experiences. While I was doing research for this chapbook, I found out about Anjuman, mostly because, honestly, I was just Googling “poet killed” or “poet imprisoned” or just trying to find out anything I could. She so clearly did not belong to this group of poets who were harmed because of their writing by a government. Even though, I mean, a lot of the language that was coming out in Western news outlets was that she was killed because of her poetry, which I don’t think is true. I mean, as Aria noted, it’s clear that she was living in a home that involved a lot of domestic violence from her husband. I don’t think he meant to kill her. So I wanted to make something about her. I was in a chapbook class with Jen Hofer at the time, so I wanted to make a book about her because she seemed so important. I was finding these attempts at English translations that were just online to honor her. It’s clear that her story made it past the boundaries of Afghanistan because she was just this rising star. She was going places with her work, and she already had this enormous readership. Also, that she was this remarkable member of her community in this big city known for its poetry. So I wanted to make a little chapbook about Anjuman, and I asked a family friend who’s from Iran if he would help me render some in English just to put into this thing that I would turn in for my class. He immediately burst into tears. We just flipped open this book that I had bought of the original Persian, and he just immediately burst into tears while reading one of the poems. That illustrated to me that this was somebody who was very powerful as a creative maker. So I made this little book, and I read everything I could about her in English. It was really interesting. I think a lot of my experience during my master’s and in my first book was recognizing the stakes. I think this is one of the things that’s really powerful about translation—is that the stakes and your ethics are just immediate. That was something that took more time with poems of my own making. With my first book, I at some point actually thought maybe I shouldn’t publish it because it seemed to really be painful for people who read it. It made me realize that I wasn’t making things in a vacuum. But I think with translation, one of the things that’s really remarkable about it is that you enter into the circumstance with that immediately. I really wanted to do something about her work and have it not just be about her death. Through Jen Hofer, I connected to this remarkable network of Persian translators. I wanted to find somebody to work with and pay them for their work. So I ultimately got connected with Marina that way. She’s not a literary translator. She’s an academic—well, she used to be an academic. I felt like she was such a remarkable partner. I was really grateful that I was able to get a grant to pay her a sizable amount for her work. I made sure that our names are both on everything and essentially tried to do everything that I could to push back against the long history of white translators who don’t actually know how to read a language, who employ somebody to provide them with literals and then erase them from the whole process. Marina too was really moved by the poems. It took us several years to put something together. To build upon my comment about the fact that with translation, the stakes are really clear because you’re the steward of somebody’s work. You know, if you’re somebody like Vallejo, who could just be translated infinitely—and is, which is amazing—it’s a little bit different versus if this is somebody who is not really translated and there’s no volume of translated English work. I feel like it was really educational for me. If I would go to AWP and talk to a stranger about the work, and they would just hear the story, they would say, “Oh, you need to lock that down.” I started to feel more and more repulsed by how frequently that happened. Then I remember I was a finalist for a scholarship, and I went to the interview, and that’s all they talked about. Like, they didn’t talk to me about my own writing or my scholarship. I was like, “I really hope I don’t get that money.” I didn’t. So I was so relieved. It would have felt really ugly to quite literally financially benefit from this woman’s tragedy. I feel like I grew up as an artist as I was working on it in general, and understood my role as a creative person in a community who has to move with ethics and care.

DN: Let’s hear three poems of Nadia’s brought into English by you and Marina. I was hoping we could hear Go, The Sun of Knowledge, and A Story.

DA: Sure. This poem is a ghazal, which is an ancient poetic form. Often, what will happen is there will be a repetition every other line at the end of the line. She loved this form and used it a lot.

[Diana Arterian reads the poems Go, and The Sun of Knowledge]

DA: Let me find this last one. It’s been really fun to edit this book, just remain in awe of her remarkable imagery and storytelling.

[Diana Arterian reads the poem A Story]

DN: We've been listening to Diana Arterian read from Smoke Drifts. Before we return to Agrippina the Younger proper, I wanted to mention the teaching guide associated with it, available on your website, which includes discussion questions, writing assignments, and a section of complementary and supplementary texts that vary widely—Joy Harjo, Adrienne Rich, Cecilia Vicuña’s poem The Disappeared, which includes the lines, “But how to speak if each syllable falls into the sea / The m of mother drifting away / other, other, where have you gone? The f of father sinking further down / ather, ather, where have you gone? They didn’t fall / They were thrown to leave us without speech to drown our words.” That section also includes two past conversations on this show—the ones with Doireann Ní Ghríofa and Tyehimba Jess. I guess I wondered, selfishly perhaps, why you saw these two conversations in conversation with your book?

DA: Oh my gosh. Well, first of all, my bookshelf is in a fight with you because it keeps falling off my wall because of all the books that I get or get from the library because of this podcast. Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s book, A Ghost in the Throat, was something—I mean, I was already deep into the Agrippina book by the time you had that conversation with her. I love that book.

DN: Me too.

DA: It feels like they are friends, the Agrippina book and Ghost in the Throat. Similarly, here’s a person who is trying to reach back in time toward a woman who was horribly wronged and of whom we only have this small remnant. I feel like because the book has such kinship—and Ní Ghríofa speaks so thoughtfully about her process—I mean, it’s essentially why I got the book and then loved it and then bought it for a dozen people. I also love that this book that’s strange and specific in its inquiry is this runaway success, which is really exciting. Then Tyehimba Jess—I got Olio I think maybe before I listened to the interview—and loved it and felt very validated that it won the Pulitzer. It’s a book that I thought was a real showstopper, and then it was venerated. But I think one of the things that was really great about that interview, and one of the things that’s great about Jess, is how he talks about developing material in response to other material. I wrote about this explicitly for the Poetry Foundation—about this idea of counter-monument poetics—and how he built so much of his book based on John Berryman’s Dream Songs, which was a book that I read in my MFA and really liked, but there was no real explicit conversation about the racist tropes of the book. He spoke about that really thoughtfully. I feel like your questions provoked really great responses about how there’s this—I wouldn’t even necessarily call it a wound—there’s just this huge injury in this book that is taught across MFA programs, and no one’s talking about it even a little bit. But I think how writing can be a means of reclamation and redress, and I think both of their work is doing that in a really aesthetically compelling way, but also, most important, I think, has a politics that’s really pointed. And I mean, I love that both of those books, The Dream Songs and Olio, both won the Pulitzer. I feel like that was really poetic justice.

DN: Yeah.

DA: I also just love that book. I mean, he’s a genius.

DN: He is a genius. Yeah. Well, we have another question for you from another. But before we hear it, let’s set it up with hearing another poem first. Could we hear After Agrippina’s Wedding to Domitius [as with Custom What Follows]

[Diana Arterian reads a poem called After Agrippina’s Wedding to Domitius [as with Custom What Follows]

DN: So this next question is from the writer and artist Daniela Naomi Molnar. In her paintings, she both harvests her own pigments and uses different water sources, both often from places of great significance. In her words, she says, “In my writing and visual art, I work with memory. I visit the edges of life (clear cuts, concentration camps, dying glaciers) to forage for flowers, rocks, and bones and to write. From these experiences, I make pigments, poetry and prose as a way to explore how art might shift memory and, in turn, our future.” Her latest book is an erasure poem of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and is described by Alicia Jo Rabins as follows: “PROTOCOLS: An Erasure is a fragmented psalm, an outcry, a fractured cultural memoir, and a gripping and timely reflection on how human beings can choose to use language to destroy—or to rebuild.” So here’s a question for you from Daniela.

Daniela Naomi Molnar: Hi, Diana. I am so happy to be speaking with you this way, and congratulations on your amazing book. One poem in your book ends with the line, “I don’t want to imagine anymore.” This line gripped me, partly because you rely on imagination very often in this project to find your way into Agrippina’s life, because often it’s the only way in. So much of what we ought to know about her has been scrubbed or dropped from a version of history that simply doesn’t value her. Yet I understand the refusal of imagination in this poem. It’s a refusal to imagine violence, which is also a refusal to acquiesce to the perpetrator of the violence. This imaginative dialectic makes me think of hyperobjects, those ecological nightmares that humans have created but can’t quite imagine, like Styrofoam or climate change. The temporal and spatial scope of these things exceed our imaginative capacity. Yet, on a daily basis, we’re also asked to imagine these sorts of impossible violences again and again. So I’m curious to hear about the times in this project when you relied heavily on imagination and the times you refused to imagine. I’m curious how both imagining and refusing to imagine felt for you and how this dialectic pertains to our current moment when our imaginations are being daily strained to imagine both profound violence and better futures.