Isabella Hammad : Recognizing the Stranger : On Palestine and Narrative

Today’s conversation with Isabella Hammad is truly like no other on the show in its fourteen year history. The main text of her book is the speech she delivered for the Edward Said Memorial Lecture in September of 2023. A remarkable speech called “Recognizing the Stranger” which looks at the middle of narratives, at turning points, recognition scenes and epiphanies; which explores the intersection of aesthetics and ethics, words and actions, and the role of the writer in the political sphere; and which complicates the relationship between self and other, the familiar and the stranger. It does all of this in the spirit of Said’s humanistic vision, reaching for narrative forms that can best reflect Palestinian lived experiences. Hammad delivered this speech, however, nine days before October 7th. The response of Israel, and the West at large, prompted her to write an afterword, an afterword that is a third of the book entire. Hammad herself had had her own turning point, her own recognition scene, where the terms of her own analysis had irrevocably changed. The afterword reflects this change, sitting at a right angle to the speech itself. The book as a whole captures this turning point within a writer in real time, preserving the gap between two selves, and we explore both on their own terms.

If you enjoyed today’s conversation, consider joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. One possible supporter benefit to choose from is access to the bonus audio archive. Isabella Hammad has contributed an extended reading from writer and political prisoner Walid Daqqa’s letter “Parallel Time.” This letter hasn’t been published in English but it was, in 2014, adapted to the stage in Haifa under the same name. The Israeli culture ministry, in response, defunded the theater. To learn how to subscribe to the bonus audio, and about the many other possible rewards to choose from, head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally here is today’s BookShop.

Transcript

David Naimon: Are you trying to finish a writing project by the end of the year? Want to make your mornings more productive? Join the Morning Writing Club, your ultimate companion for starting your day with creativity and focus. Whether you're a seasoned writer or just starting out, the Morning Writing Club offers the perfect blend of community and motivation to jumpstart your writing routine. Author and Rose Books publisher Chelsea Hodson started this club to provide resources, accountability, and community for writers, no matter where you live. For $9 per month, you get access to the morning accountability Zoom session that Chelsea hosts every weekday morning, two monthly Zoom Q&As with authors and publishing professionals, the chance to have a one-on-one meeting with a literary agent, as well as two years of archived videos, craft essays written by Chelsea, and so much more. Visit www.morningwritingclub.com to learn more and make your mornings count. Today's episode is also brought to you by Signs, Music, a masterful poetry collection by acclaimed writer Raymond Antrobus that details imminent fatherhood and the arrival of a child. Victoria Adukwei Bulley says, "Signs, Music is a prayer for a world that might yet look tenderly upon young black life." It also has what Will Harris calls a “level of genuine intimacy,” exploring both the joyful and vulnerable moments of parenthood. Signs, Music presents a moving exploration of what it means to bring new life into existence, of the changes and challenges that inevitably come to pass, and of the hopes we carry for future generations. Signs, Music is available now from Tin House. Shortly after I recorded this conversation with Isabella Hammad about her new book, Recognizing the Stranger, I went to New York City, brought there by Jewish Currents, to moderate a conversation between Dionne Brand and Adania Shibli as part of their all-day event, an event that almost didn't happen, as despite a year of planning, Brooklyn College canceled the contract nine days before the event, claiming there was a leak in the Performing Arts Center auditorium, even though many of the Jewish Currents events were happening in other spaces in the complex, spaces without that leak. Masha Gessen wrote about the dubious circumstances in The New York Times in an opinion piece called, “The Organizers Are Jewish. The Cause Is Palestinian. This College Won't Be Hosting.” I bring up the Jewish Currents event because my conversation with Isabella just before I went was so unlike any I've ever had in the 14 years of doing this because of unique structural elements in the book that capture a change in the author in real-time. My conversation with Isabella because of this, became part of my conversation with Dionne and Adania. Now that I'm back in Portland, recording this intro to the show, with everything that happened during the Jewish Currents event still reverberating in me, I find myself now wanting to frame the conversation with Isabella through everything that happened in New York. Two of the panels near the end of the Jewish Currents day of events, a Jewish panel called Judaism and Jewishness Beyond Zionism, and a Palestinian one called Palestinian Liberation After the Destruction of Gaza have stuck with me because of their intensity, an intensity that reflects, I think, the urgency of the moment, but also how these people, particularly on the Jewish panel who had fierce disagreements on many things, could nevertheless face roughly in the same directions, both demonstrating the need for coalition building across differences, differences that often sink movements, where I'm left with both an irreconcilable set of feelings inside me, but also with the hope from these panels that people aren't getting lost in differences of language and vocabulary or lost in real differences in philosophy that aren't the most important differences, that they aren't turning inward and doing a circular firing squad, something Naomi Klein and I puzzle out in part one of our conversation about the left's relationship to language that can get in the way of effective coalition building. I bring all this up, these panels that felt fraught, full of disagreement, and sometimes outright contradiction, and yet were also allowing for some of these things to simply remain unresolved in order to come together for a shared purpose because it relates to something extremely unusual in Isabella's new book, a book that was made from the Edward Said Memorial Lecture speech that she gave almost exactly a year ago, a speech about many things, about narrative, about epiphanies and turning points and recognition scenes in narratives, both in general, but also in particular, narratives of Palestine. A speech that is philosophical about questions of self and other, about what writing is for, about the tensions, confusions, and mysteries between words and actions, and perhaps most notably about the middles of narratives and how it's hard to know if you're at a turning point until after the fact. Nine days after she delivered this speech, October 7th happened, and with her witnessing of the Western world's response to Israel's clearly stated aims, not just to collectively punish a long-standing captive civilian population, shutting off the entry of food, water, medicine, fuel, and electricity, but also referring to the siege as one against human animals as a war between the children of light and the children of darkness, a rhetoric that gave no pause to the West and its unconditional support for it, Isabella felt prompted to write an afterword to the speech, an afterword that is a third of the book entire. The terms and mode of the afterword are very different than the speech itself. I wouldn't say it works against the speech, but that it is at a right angle to it, that there is a legitimate gap between the two, and if not exactly a contradiction between them, a generative unease. Part of this is simply a shift in priorities of what to center, of what to foreground as we reach nearly a year of the indiscriminate destruction of Palestinian life and Gaza. But it is more than that, Isabella herself has had her own recognition scene or turning point where the terms of her own analysis have shifted in real-time. The terms of the afterword are different because Isabella herself is now different, and the book captures this disjunction between two selves, this metamorphosis in real-time, and preserves it in all its complexities and countercurrents. I could have glossed over this gap in the book between the two parts or focused only on the speech, the main body of the text, the purported main text. But I decided to take both parts seriously on their own terms. This approach, I think, enhances the unease, not between Isabella and I, but within the book itself, and perhaps within both of us individually. But I hope it does so in a generative way. I made it challenging for both of us, I think, emotionally, where we explore something in the book on its own terms, that she herself wrote not that long ago, but then leap across to the Isabella of now and interrogate it or reflect on what is more vital to center now and why. Because of this, I sometimes have my own independent sense of unease where I'm exploring something I myself wouldn't otherwise center, but doing so because of the words before me. Again, I don't want to give the impression she is disowning the speech, but she is reorienting herself both to it and a new sense of herself in relation to Said and to Palestine. One of many examples of this that I want to mention before we begin is my bringing up and making meaning of things around Jewish identity and also around Judaism as a religion. Regardless of whether this was before or after October 7th, I wouldn't, generally speaking, be bringing up in a major way Judaism and Jewishness to unpack the meaning within them with the Palestinian guests unless their work itself was explicitly doing so. But the speech itself in no small part does just this: it engages with encounters with Jews with Said's meditations on Jewishness in relation to what he calls Palestinianism and on both Freud and Moses. Even knowing how the afterword moves decidedly in a different direction, we do explore the speech on its own terms, which involves, and I'd suggest, invites me to make meaning from it as a Jewish reader. We also together then look at what we both think are the better priorities of the moment. The last time Isabella was on the show, last year, she contributed an extended reading from writer and political prisoner Walid Daqqah, his letter from prison, Parallel Time, in a translation by Dalia Taha, a letter that, according to Isabella last year, had not been published in English, though in 2014, it had been adapted to the stage in Haifa until the Israeli culture minister defunded the theater in response. Since then, Daqqah, the longest-standing Palestinian prisoner, one of 38 years of imprisonment, has died. Erika Guevara-Rosas, of Amnesty International, wrote after his death that even on his deathbed, Israeli authorities denied him adequate medical treatment, suitable food, and prevented his wife and four-year-old daughter from saying a final goodbye. This reading joins many other incredible contributions from everyone from Dionne Brand’s to Natalie Diaz’s. The bonus audio is only one of many things to choose from if you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. Another possibility is getting a sampler of issues of Mizna, the magazine of Arab American culture and literature, helmed by the Palestinian poet George Abraham, who I had the pleasure of meeting at the Jewish Currents event in New York. You can find out more about the rewards, resources, and gifts that you can get by joining the community at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. All of this to say, this unsettled book I think is a gift to us all, and I hope whatever gaps in your own analysis and self-conception that might come to the fore as you listen and engage with it, or any gap or disjunction revealed between you and what you hear, that we can hold the contradictions and gaps in such a way where those of us who care about stopping the genocide can still be facing the same way. Now for today's conversation with Isabella Hammad.

[Music]

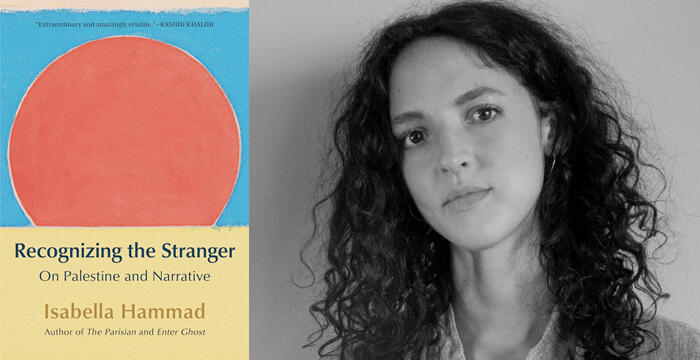

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest, British-Palestinian novelist Isabella Hammad, grew up in London, studied English at Oxford, did a graduate fellowship in literature at Harvard, and an MFA in creative writing at NYU. Her debut novel, The Parisian set in early 20th century Palestine at the end of Ottoman rule and at the beginning of the British mandate announced an important new voice both in Palestinian literature and more broadly in the literature of the Anglophone world. The Parisian was the winner of the 2019 Palestine Book Award, the Sue Kaufman Prize from The American Academy of Arts and Letters and named a Book of the Year by everyone from LitHub to Vogue to Amazon. Hammad is a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree named in the once a decade Granta list of best young British novelists, a Lannan Foundation Fellow, and her writing has appeared everywhere from Conjunctions to The Paris Review to The New York Times. Last year, Isabella Hammad and I spoke between Portland and Palestine about her second book, Enter Ghost, a book set in contemporary Palestine and Israel that follows a Palestinian theater group aiming to put on a production of Hamlet in the West Bank. Since we talked, Enter Ghost was picked as a best book of the year by The New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, both the Sunday Times and the Times in the UK and many others. It was a long-listed for the Ondaatje Prize, was a finalist for The Chautauqua Prize, was shortlisted for The Women's Prize for Fiction, The William Saroyan International Prize for Writing, and The Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize, and was the winner of The Aspen Words Literary Prize in the Royal Society of Literature's Encore Award for Best Second Novel. Also since we talked, she, along with other prominent writers from Michelle Alexander to Emily Wilson, to past Between the Covers guests Naomi Klein, Morgan Parker, Lorrie Moore, and Kate Zambreno, withdrew from The PEN World Voices Festival in protest of PEN America's relative silence and inaction around the siege of Gaza and the fate of Palestinian writers, journalists, and cultural institutions in comparison to both other conflicts and the stances of other PEN chapters around the world with regards to this one. Given that today's conversation is partly about the power and limits of words, I'll read one paragraph from that open letter in anticipation of our discussion. Quote, “Scholars are increasingly reaching for novel words to describe the scope of Israel’s cultural genocide. Words like ‘scholasticide’ are invoked to describe the elimination of systems of education and ‘epistemicide’ to describe the erasure of systems of knowledge. In contrast, PEN America, took four and half months to utter the word ‘ceasefire,’ then only with a vague ‘hope’ for one that is ‘mutually agreed,’ rather than a clear call. We expect more from an organization that exists for the express purpose of protecting freedom of speech and thought, and advancing a vision of our common humanity.” Last fall, Isabella Hammad delivered the annual Edward Said Memorial Lecture, a speech called Recognizing the Stranger, a speech that now, in expanded form, has become a book of the same name. Rashid Khalidi says, “Hammad shows how art and especially literature can be much, much more revealing than political writing.” Similarly, Max Porter calls Recognizing the Stranger, “A pitch perfect example of how the novelist can get to the heart of the matter better than a million argumentative articles. Hammad shows us how the Palestinian struggle is the story of humanity itself, and asks us not to look away, but to see ourselves.” Finally, Viet Thanh Nguyen says, “An urgent work for a devastating time, Recognizing the Stranger proves that Isabella Hammad is as fine a critic as she is a novelist. Following in the tradition of Edward Said, she demands an ethical, political, and artistic confrontation with the text, the world, and the other. It is hardly a surprise that she is one of our most astute writers when it comes to Palestine.” Welcome back to Between the Covers, Isabella Hammad.

Isabella Hammad: Thank you for having me back.

DN: You open your lecture with an uncertainty around time where you say, "When I was wondering what to talk about in this lecture, I started thinking about Edward Said and lateness as a point of departure. Then I went back to his early book Beginnings. And then I decided after all that I preferred to start in the middle.” I wanted to start here with time and also timing. You wrote this speech in August of last year and delivered it nine days before Hamas' attack on October 7th, and Israel's still ongoing indiscriminate destruction of Palestinian life ever since. I want to read part of another open letter as a way to begin to talk about the complexities of time. This is an excerpt from near the end of it. “Each provocation and counter-provocation is contested and preached over, but the subsequent arguments, accusations, and vows all serve as a distraction in order to divert world attention from a long-term military, economic, and geographic practice whose political aim is nothing less than the liquidation of the Palestinian nation. This has to be said loud and clear, for the practice only half declared and often covert is advancing fast these days, and in our opinion, it must be unceasingly and eternally recognized for what it is and resisted.” This language could have been in any number of open letters over the last 10 months, but it was actually written nearly 20 years ago. A letter signed by 18 writers, including John Berger, Toni Morrison, Arundhati Roy, Naomi Klein, Howard Zinn, and José Saramago. It could have been written not just in 2006, but today, or in 1982 or in 2014. Everything since October 7th is echoed in that 18-year-old letter and many other letters going back decades. Yet, at the same time, everything since October 7th has stood out for, by many metrics, it has been worse than the original Nakba 75 years ago. I say all of this because what October 7th put into motion prompted you to write an addendum to the speech, an addendum that is a third of the book entire, not a reappraisal of the speech necessarily, not a counter to it, but perhaps it's oblique to it insofar as its tone and approach is quite different. I wondered if you could speak to your speech in time and why you wanted to bring the time since your speech into a consideration of it as you presented to the world as a book.

IH: Thank you David for that very thoughtful introduction and for reading part of that letter that we wrote which I'd like to speak a bit more about perhaps as a kind of an experience of a collaborative writing that was actually in its way quite wonderful, talking about writers working together and also that excerpt from that older letter. I mean maybe this partly answers your question about the the afterword, about the genocide, but what's strange as you say or what feels sometimes uncanny is that when we look back at descriptions of the continual Israeli attempt to obliterate Palestinian forms of life within historic Palestine, they're often uncannily just describe what's happening now. It's this thing where it's both the same and it's new. It's a continuation of a long-standing policy, it's just that it's in the open. So, I think what has changed, apart from the complete impunity with which they are conducting their military campaigns, now spreading to the West Bank, but also the ways in which everyone can see it clearly, that's the change. It's actually an internal one. I guess what was weird in a way about my lecture was that I was getting there on my own, but thinking it through story, it took me a while to work my way through it to find that argument about turning points and seeing clearly. Then actually, I think partly the afterword is also about my own seeing clearly. It’s about myself as well. I think that that has to do with a quite major loss of faith in humanistic principles and in the tradition of humanism. Edward Said was a humanist and he spent much of his career trying to recuperate humanism or to find ways in which the tradition of humanism could be a critical one, could be one that develops, that changes, that is not discriminatory, that can expand, that can be adopted. There are other thinkers who work like this, like Sylvia Wynter, even Fanon, they have this attitude that we want to raid the conceptual armory of the West, of the Western philosophical tradition and use it to our own purposes. We are also human. We expand the definition of the human. I think that over the course of these 10 months, I found that more difficult to hold on to more and more. That's my moment of recognition, which is what I described to some extent in that afterword.

DN: Oh, I didn't respond because I thought you were going to speak to the World Voices open letter.

IH: The letter was interesting because afterwards, many members of the board defamed us and said we were against free speech. In the letter, we really specifically say, “This is not about free speech. We're not against other people that they're including in the festival. That's not the point of this.” Also, the idea that there should be free speech about a genocide is crazy. It's just crazy. It's a totally lopsided ideological element of American culture, that the highest good is free speech, rather than that free speech is a side product of a just political system, but without any reference to what the content of the speech is. Obviously, it's also completely hypocritical because it's always free speech except for when it comes to Palestine. There was a real twisting of our words but what was wonderful about the experience of doing that letter was actually that we were a group of writers, many of us didn't know each other and we all felt the same and we had this collaborative writing experience of writing this letter. We all agree this was way better than being in some festival. This was a way of articulating something together and nothing about it was coercive. We just put it out into the world and we said if anybody wants to sign, they can sign.

DN: As you suggested in your answer to my question, many Palestinians talk about the Nakba, the original dispossession in exile, not as an event or not only as an event, but as an ongoing forward-echoing process. In a way, it's not really surprising. It is and isn't surprising, the uncanniness and the timeliness of the fact that you are talking about the middle of narratives, about turning points in narratives in this speech that is written and delivered before October 7th, about how hard it is often to know what a turning point is until after the fact with you thinking of Israeli apartheid in light of the Berlin Wall and South African apartheid asking where in the narrative we now stand without knowing how to answer the question that you pose. Uncanny because October 7th feels like a turning point as it is happening, but a turning point toward what seems unclear as you ask in the afterword, are we at the beginning of a decolonial future or of another more complete Nakba? This reminds me of a passage in the Palestinian-American poet and performance artist Fargo Tbakhi's essay Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide where he says, "To write in solidarity with Palestine is to write amidst the long middle of revolution." Later he says, “The long middle is not a condition of time; we might be nearer to the end of revolution than the beginning, we might be nearer liberation than defeat, but our experience and our actions exist within the frame we can see, the frame of the long middle. Liberation is the end, but it is a geographical end rather than a temporal one, a soil and not an hour. We move towards it— sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly, but always. It is the location by which we orient our movement. We know it because it gets closer, not necessarily because it comes sooner.” I quote this is a way to begin to discuss your choice, to discuss turning points as a way to deliver an Edward Said Memorial Lecture and as a means also to talk about the shape or form of Palestinian narratives.

IH: Yeah, it's beautiful, that essay. I mean, I guess the point about turning points is that they're human constructions. That's what Said says about Beginnings. That's giving a kind of a marker in the sand for difficult knowledge. In fact, he uses the word difficult knowledge for the issue of Beginnings, among other examples. Freud's, many of Freud's ideas, he said, were already in existence, but Freud marked the beginning when he wrote them down and this gives us this marker to inaugurate some of these ideas. We can say the same thing about turning points. They're something we've made up for ways of making sense of things, and that's just a natural human tendency and we make narratives and that's how we make sense of the world and how we move through it. They might change, they might overlap, they might be abandoned, you know. But I think that's beautiful in the essay that you just quoted from the idea that the endpoint is always in sight actually. The endpoint, we know what the endpoint is. We don't know what that endpoint's going to look like. We also know it won't actually be the end in some ways. Liberation always is followed by many complications and state building and all of these things and everything else; we know from other anti-colonial movements and their afterlives. I think I was interested in turning points because of the way I've written novels so far and the way I've written fiction in general is with a kind of concern for this relatively classical shape of a story where there is change, this change over time. I think this is a little bit passé in a way, it's like an older idea about how you write character. But I'm really interested in it. I guess part of the reason I ended up writing the lecture about that is I was wondering why am I so interested in it, why am I so interested in people's capacity or not for change. I always ask people what texts did they read, what experiences did they have that changed their attitudes to things. What I'm really usually asking about is what changed their attitude to Palestine. I'm always interested in the development of political consciousness, how it forms, how we understand ourselves, not only as individuals but as part of groups, as part of something larger, as part of an epoch, and that makes its way into my writing. I unpacked that and realized it was because of Palestine quite specifically.

DN: Well, another thing that Fargo says in Notes on Craft is that “Craft is a machine built to produce and reproduce ethical failures; it is a counterrevolutionary machine.” This reminds me of a recent guest on the show, Vajra Chandrasekera, whose fiction interrogates Buddhist hegemony in Sri Lanka and where we also talked about the parallels and resonances and divergences between Israel and Sri Lanka. He critiques world-building, which he contrasts to writing on similar terms to how Fargo critiques craft, the potential and power world-building has to reiterate the world as it is. I myself feel that uneasiness in talking about words with you when what we need more than anything are actions. I think of what Sally Rooney said as part of your conversation with her where she's talking about engaging with this endless stream of horrors on her phone or on her screen where she says, “Everything in me rebels against what I’m witnessing. And I think of everything I’ve written to you until now, about geopolitics, about public opinion in the west, and I think: how pointless! Some celebrity said something on Instagram, and I’m asking you whether this is cause for optimism, really? When every time I pick up my phone I’m seeing footage of destroyed neighbourhoods, grieving mothers, mass graves. It makes everything I have to say feel absurd and disgusting. In these moments I lose faith in language, in conversation, dialogue, everything. The only word that means anything to me at such a moment is the word: No. And all I want to do is repeat it to myself again and again, seeing these images of devastation and suffering. No, no, no.” I feel this, both this speechlessness and refusal, but thinking of Adorno's quote, or some would say misquote, that it is barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz, something that to me seems patently false insofar as some of the most vital and enduring and lifesaving art engaging with the Shoah, including incredible poetry, has been made in its shadow. It makes me wonder if the most enduring art in the face of speechlessness somehow contains the “No” of Sally Rooney in it. But I raise this because this uneasiness around language and this questioning of what it means to be a novelist at all, but particularly at this time, the examination of not only the power of language, but the power of language to do harm and to reiterate the world, not only the failure of language but also the ways language can fail by pretending to be more than it is, all of this uneasiness is baked into and animates your speech. I wondered if you could speak to your own self-questioning a little more about you as a maker of novels in touch on some of those questions and anxieties about what it is that you do.

IH: Thank you. It's a great question. There's so much to say. I think before I talk about my own grappling with those different questions, I don't want to say that we always have to bring it back to Gaza. The other day, I was in a conversation with a writer there called Mahmoud [Rashed], who's been unable to leave, you may know about him, you're nodding. He said lots of things, but he said, “It's not enough to feel with us. You have to talk about us,” which I think when we prioritize that, when we return to this as the priority here, it's okay to have all this unease and to talk about the difficulties of speaking, the compromises of inherent in speech, the lies we tell ourselves about the power of language and how that's bound up within industry and particularly in this country, in the US, and balance that with actually the importance of continuing to speak. Those things exist at the same time and we can engage with that and talk more about that. But the most important thing is to keep talking about them. I find that helpful. It also humbles you a bit. It's like, yes, you’re out of your head a bit about what's the value of saying anything? But we do have to continue to speak because this is significant, not only for those people who are there who've been slaughtered, who are being slaughtered, and not only physically but in their minds, I don't know how they're surviving mentally under that, being moved from place to place, being starved, being imprisoned, being assaulted, being so frightened they can't sleep. But the significance is huge for everybody on the planet. The fact that a population can be so disposable is terrifying. To me, it's very linked with the ways in which we're destroying the planet as well. It's this kind of savage removal of any boundaries or any pretenses or the pretenses have been worn away. That's really frightening and should frighten people very seriously for themselves. Having said that, I do continue to feel complicated about this issue of speech, and particularly in the West, where language is focused on as the most important thing. It does obviously have to do with the fact that the story of Palestine has always been one of language to some degree. It's always been an issue of naming. Palestinians were famously denied the ability to generate for themselves, and were always subordinated to this story of Europe and Europe's crimes for which they paid the price. The language was given to the colonizer, to such an extent that even cities are renamed. A language is overlaid, so reclaiming certain words like the word Nakba, the word Nakba is more than just genocide, more than just apartheid, more than just settler colonialism. It's all of these things, it’s both a specific event in 1948 and it's an ongoing process of obliteration that incorporates all of these elements to different degrees and in different ways and in different geographies with different tools. So to use the word, to use the Arabic word is very important to conceptualize it properly. Language is both very important but the focus on language in the West and on the slogans, all of this seems to be just a huge distraction from what's actually happening. Then it becomes a battle over words about being politically correct about using the right phrase. It has to do with distance because they're not close to the bombs.

DN: Yeah. Well, in this speech, you bring up Aristotle in a way that harkens back to Aristotle in your last novel. In the speech, you talk about what Aristotle called anagnorisis, narrative moments of recognition, like the example you provide when Darth Vader says to Luke Skywalker, "I am your father," and then everything that has already occurred suddenly takes on a different valence. In Enter Ghost, there is a debate about Aristotle's notion of catharsis in relation to the theater, and more specifically in relation to the shape or form of the Arab story and the Arab relationship to theater. There's an anxiety here about what theater does and doesn't do, where at one point the director of this Palestinian version of Hamlet says, "There's a danger that 'art might deaden resistance, by softening suffering’s blows through representing it.’” Again to return to Fargo's piece Notes on Craft, he speaks into this as well about the Brazilian anti-fascist theater maker Augusto Boal who asserted that Aristotelian narrative structures were coercive tools of the bourgeoisie that in Fargo's words were "serving to purge an audience’s revolutionary emotion and with it the obligation to intervene in an unfolding narrative as an active participant. This coercion is intended to make us feel as though world-historical events are beyond our grasp, that we have no agency within them and should remain within the status quo.” He goes on to quote Boal who says, “The poetics of Aristotle is the poetics of oppression: the world is known, perfect or about to be perfected, and all its values are imposed on the spectators, who passively delegate power to the characters to act and think in their place. In so doing the spectators purge themselves of their tragic flaw—that is, of something capable of changing society.” As an aside, I'll just say I love that the tragic flaw is the thing that's capable of changing society. “A catharsis of the revolutionary impetus is produced!” Back to Fargo who concludes: “Palestine requires that we abandon this catharsis. Nobody should get out of our work feeling purged, clean. Nobody should live happily during the war.” Given that this is an enduring preoccupation of yours, I wonder if you could talk about the strategies you use to write narratives or counter-narratives that prevent this counter-revolutionary catharsis or make it less likely. I suspect simply bringing this open question into the work itself as a question might be part of that, but talk to us about your thoughts or your own puzzling out as a storyteller in relationship to how to inoculate or attempt to inoculate your own art from becoming that discharge of revolutionary impulse in a counter-revolutionary way.

IH: Yeah, it's always a fear. That's why they debate it in the book. They debate the value of it. I have this feeling about Greek tragedy, it came out of ritual, it came out of Dionysian pre-democratic rituals and it converged with democratic principles and the structure of the state. It contained the ritual, the carnivalesque, the wild, the emotional within a structure that was coordinated by the powers that be as a way to purge feelings from the population. Obviously, it's not only that and there are lots of other things happening in the different plays, but it seems to me that that's the structure and that in some ways, a tragic hero is like a scapegoat that allows the population to release something and then to go back to being a docile population, which is also what Dionysian ritual allowed to do to purge all of those feelings, then you go back to being docile because you've been alleviated of some of that pressure. Obviously, the person we've not mentioned is Brecht, who very much signed on to this idea and wanted to alienate an audience specifically in order to make them conscious of the social and political context in which they're living and then to do something about it, to take arms against a sea of troubles as it were. So I am concerned with that. I guess in a way that was why my book, the book about the play, ends in medias res, so it ends without the play being complete. It denies catharsis in that way. I don't know if this is inherent to the novel form, if the novel is inherently tied to its bourgeois aesthetic origins if it's hard to unshackle from that. I don't think that's true because there are lots of novels that are politically committed that do engage with struggle in direct ways and are galvanizing as well. I think that we shouldn't close down how readers respond to texts. We can't actually control how they read novels, how they respond to them, what they take from them. That wildness and that uncontrollability is part of their power and it's part of what's magic about novels. It's a category error to suggest that the novel is going to itself, someone's going to read a novel and then go into the street and march, but it can be part of a developing political education that allows them to take action. I think that it's not so clear, but I won't lie that that fear that revolutionary fervor is sapped by the well-being feeling that comes after watching something or reading something terrible, it is a counter-revolutionary emotion. But another counterargument is that it's very tiring to fight the fight. We're all exhausted at the moment. I mean, I'm exhausted and I know everybody's exhausted. You can't expect us to remain at that high tenor all the time. It's a kind of multifarious process that requires also contemplation, it requires also moments of calm. They all feed each other in different ways. It's a bit of a messy answer.

DN: It seems like it has to be a messy answer.

IH: Yeah.

DN: Before we move on to the part of the speech that is interwoven most deeply into my own life and in my own work, I want to spend one more moment with this mysterious relation of language to the world. This question, which is probably the most asked question in the world of writing and art making: What does writing do in the world? I think of Wisława Szymborska's famous line: “I prefer the absurdity of writing poems to the absurdity of not writing poems.” I feel like if I press on this question of words in relation to the world, I can end up with one feeling, and if I press further, I end up in the opposite position. If I stick with it, it flips again so maybe this speaks a little to the messiness of the answer you just gave. For instance, I think what we need now is the cutting off of arm shipments and arms embargo, the use of material actions to leverage an outcome, not more rhetorical, hand-wringing. On the other hand, words must be powerful, and they must be threatening to the powerful when we see the long-standing silencing around the Palestinian narrative rise to new levels, where the largest book fair in the world cancels past Between the Covers guest Adania Shibli's ceremony, a ceremony celebrating her and her panel, where she is supposed to receive an award for Minor Detail, or Masha Gessen, who was supposed to receive the Hannah Arendt Award for Political Thought, named after a Jewish intellectual who herself was opposed to a Jewish state, and the event was scuttled because Gessen criticized that state. But I also see people using words not to act, proclaiming they care, but needing the perfect conditions within language in order to do so. If someone says the wrong word—genocide, settler colonial, or river to the sea—it keeps them on the sidelines over and against their supposed concern about the crimes being committed. I see many people facing away from the conflict and policing language, critiquing what open letters were signed, having arguments within a purely rhetorical space, as if it were true that if we had the correct language, we would have the correct outcome. For me as both a writer and an activist, but primarily the former, I feel that tension inside myself between the complexities I want there to be in language, and the imperfect necessities of political speech used as a tool to create material change in an unfolding, pressurized moment. I would have never written any of the open letters that I signed with the language that they used, but they pointed in the right direction, for instance. This is my long way of hoping you talk a little bit, you've already nodded in this direction, but if you could talk a little bit about your piece in The New York Review of Books called Acts of Language, which feels in conversation with your speech and which opens with how you are struck by the verbal contortions writers are going through to avoid engaging with Gaza, how so many writers are lamenting the speech of pro-Palestinian protesters rather than focusing their energies on the actual violence that these protesters are protesting. You give examples like Judith Shulevitz in The Atlantic who says about the campus protest at Columbia, "A voice breaking the calm of a neoclassical quad with harsh cries of ‘Intifada, Intifada’ is not a harbinger of harmonious coexistence." But most notably, you engage with Zadie Smith's essay, Shibboleth, where she focuses on and centers the language of the protesters much more than the genocide itself, and goes so far as to call the language in rhetoric when it comes to Israel-Palestine as themselves weapons of mass destruction. Talk to us a little, as you do at length in the essay about what the focus on Palestinian speech and/or speech about Palestine is obscuring what work it is doing intentionally or unwittingly when we stay in that space of centering the speech.

IH: Well, first to reflect on your point that there are some people who feel morally cool to do something but reject the terms in which Palestinians describe what's being done to them, I think that the lecture I gave is about recognition, but the opposite of recognition is denial. I think that, first of all, the West is in denial in many ways. Less and less so, more and more people are confronting what's happening among the populace, but the institutions, the culture institutions, the universities are denialist institutions, and I think it's quite helpful to talk about denialism as a phenomenon, which is a denialism not only about Palestine, but about structures of empire and genocidal histories which are not acknowledged. I mean, Germany committed more than one genocide. What about Namibia? These things haven't been acknowledged in the Court of Justice and there's been no compensation, there's been no retribution. There's an ongoing denial about these histories, which are now coming to the surface. We're seeing the tip of the iceberg, but there's a huge mass underneath. There's no wonder that people are in denial because to confront that reality is to confront many things that structure their lives and structure their societies. That's really scary. I understand that that's really scary. The liberal response is to try to keep a little bit to be said, “Well, that bit's bad.” “Yeah, the killing of the Palestinians is bad, but let's keep this bit or let's keep that bit.” But the whole thing is rotten and it's all connected and that's what's coming to the fore. It's like gangrene, you open it and it's all rotten down to the bottom. That's terrifying. To face the front, to properly look at that, I understand it's really difficult for people. But I think denial is on a spectrum. It can take people a while. I would say that those people who are having trouble with terminology, they're having trouble confronting some of these things, some of that is because they're actually on a journey. That's also okay, you know. In any movements, we need coalition building, not everybody's going to agree on the same things, you have to work together. Sometimes that means just getting the bare minimum, the ceasefire is the bare minimum. Can't believe we haven't even got a ceasefire. Then we can talk about liberation and the afterword. But again, I mean, yes, the issue of language that I wrote about in that essay is related to what I was saying before about terminology, but it is also just a way of distracting about getting up in arms about young people who maybe they go overboard or they're not sure what they're doing or they're really clear. I think it's probably very small fringe who you might not agree with but I actually went to visit the students at Columbia and they were amazing. They were so organized. They really knew what they were doing. They'd studied so hard. They were watching movies together. They were having discussions. It was amazing. It was admirable. I tell you, they were led by Jewish students. The Jewish students, they're the LGBTQ students, and they're the Black students. So this whole idea that Jewish students are being threatened is just bollocks, it's just a way to try to protect Zionism, which is an ideology that is unfortunately inherently genocidal. I know that that's a difficult thing for people to say and they're now trying to police this language to make it illegal to say that, which also shows you more of what I'm talking about. But also one of the issues that I was trying to confront in that essay was the misguided attempt to silo what's happening on university campuses from the reality in Gaza. They are connected so you can't divide and say, “Well, okay, let's just take a step back from the violence and talk about the ethics of what people say rather than to see it all as connected,” and I think that's what the students valiantly have been trying to do which is to say, “No, no, it's all connected and these universities that are sending this money or that are involved in these funds, they are connected. Our speech on campus cannot be divided from that.”

DN: Well, I want to move toward talking about turning points, recognition, scenes, and/or epiphanies in relation to otherness and/or the stranger. But first we have a meta question around this for you from another about whether you had your own recognition scene about writing about recognition scenes. This is from the author Alexander Chee, who himself has declared that Recognizing the Stranger has changed him, that it feels both prescient and eternal. He is the author most recently of How to Write an Autobiographical Novel and the upcoming book Other People's Husbands. So here's Alexander Chee.

Alexander Chee: Was there a particular moment that inspired your essay for the Said series Recognizing the Stranger of the kind you describe in the essay, one of those moments when you somehow brought out in someone the recognition of a Palestinian’s humanity, yours, someone else's, or was the inspiration found in reading Hamlet for your new novel, or some mix of these things?

IH: That's a great question. Thanks, Alex. I don't think I had a big recognition moment, but I am interested in being wrong. [laughter] I'm interested in what it means to be wrong. It has also to do with the discomfort in the culture with being wrong. People are very uncomfortable with being wrong, with being told they're wrong, with acknowledging they've done something wrong, or that they've mis-conceived something. I find it very interesting, just as a human being existing in the world. I'm just very interested in moments in life in general. This is a banal answer in a way, because there was no some revelation, but it's something that happens repeatedly in life and I'm just very aware of and fascinated by, which is when you think something is the case, and then you're blindsided by the revelation that it is completely other than you thought, that kind of experience, it's like when the edge of your awareness comes into view, and I find that fascinating about what it means to be human, and actually as a kind of corrective to solipsism, or to any sort of fear that it's only your consciousness and everybody else is whatever the thought experiment we used to do as children, like is it just me and everyone else is a mirage? It's when you realize that you're just a little thing in the world and there are millions of other people with other ways of living and seeing the world. I think that fiction is particularly positioned for investigating that. That's why my work is peppered with moments like that, not necessarily grand turning points, but also just moments where a character confronts that limitation, that feeling of wrongness, which I also talked about in the lecture. That I think is creatively where it came from in a sense, combined with what I said before about always being concerned with the development of people's political consciousness and how people confront that wall of understanding when it comes to Palestine.

DN: Well, it's the first step toward talking about not just recognition scenes, but recognizing the stranger, the notion of otherness, and what recognition in relation to the other actually means, I wanted to start with an anecdote you share in the speech. One thing your speech looks at is the notion of epiphanies and how the short story form is shaped around them, classically speaking, and what the implications of this are. You share an anecdote about your visit to a kibbutz, and then your subsequent failed attempts to turn this anecdote into a short story in its normative form. To set up some questions for you, I was hoping you would share with us about the Israeli you met, the story he shared with you, and its after-effects on you, as you do in the speech.

IH: Yeah, the story was that he left his post. He was guarding the fence, the partitioned fence on the Gaza Strip, and nothing happened, he was young and then he saw a naked man walking towards him and he was supposed to shoot anybody who came close but he didn't because the guy was holding a photograph out and was clearly naked and unarmed and it was kind of a shock factor. That made him have his moment where he was still in shock when I had this conversation with him. But I guess what it led me to think about was the question of persuasion and that this had obviously had an effect on this one young man, this stunt by this guy who was holding out a photograph of a child who presumably had been killed by Israel and that it had had an effect on this one soldier, okay. But he had to stand naked, he had to show himself literally naked to the soldier and put his life on the line in order to beg him to recognize that he was a human being. I was interested in the story and I was interested in that because it very much plays exactly to that form of sudden coming to knowledge, essentially, that I was interested in. But it never worked as a story. It didn't function and I think it was because it was all about the soldier. It wasn't about this guy who was so desperate that he was willing to be shot naked with this photograph.

DN: You also talk about how when writers are brought to PalFest, the literature festival in Ramallah, that you are always moved to see the scales fall from people's eyes, to see how opinions change on the ground rather than just simply in discourse. But also how every time you see this, there's also a despairing sense of deja vu. This is echoed by something you quote also in the speech by Omar Barghouti who says, talking about witnessing the "aha" moment when an Israeli realizes a Palestinian as a human being, “How many Palestinians have to die for one soldier to have his epiphany?” You've talked about how many Palestinians have devoted their lives and careers to inducing epiphanies in others. But also how you are often asked if your aim is to educate Westerners, a suggestion you've found both reductive and sort of undignified. You propose another model about thinking about your work that's inspired by a book called Radius. I was hoping you could talk to us about this alternate framing, rather than creating art that is meant as an epiphany machine. What is this other model that you put forth?

IH: Well, we're talking about the question of persuasion which leads on from your last question to try to persuade the other that you're a human being is what Palestinians have done for a very long time to try to prove that they are human, to humanize themselves, to write stories that humanize Palestinians. I think it's insane to me that human beings should constantly have to humanize themselves. I mean, it's not on us to prove that Palestinians are humans. It's up to the other to overhear. I think that purely rhetorically, live aside the ethics of a politics of persuasion, but rhetorically, it's much more effective to overhear than to feel like someone is trying to persuade you. It's actually much more effective to hear dialogue, to hear different points of view, and to develop your understanding that way. I think that that is more effective when we think about what Mahmoud [inaudible] said about you have to keep talking about us. It's not that we're trying to persuade someone, but we'll keep talking and they'll listen. When they're ready, they'll listen. That's just a more effective way to go about it. It has an effect on a craft level. My first novel, I started when I was very young, I just left college so I had more naive ideas about narrative then. I think it's okay, just to admit. I was like, “I'm going to write a novel about Palestine before the Nakba.” But even then, I didn't want there to be persuasion. I didn't want there to be any overt agenda. I didn't want there to be philosophizing. I just wanted it to be before the Nakba. Then I read a novel with all sorts of characters, all sorts of things happening. Obviously, some of my political views make their way in, but I wanted it to be quite restrained in that sense. It came from this instinct also that to try to persuade is not very effective. You may persuade individuals who may have their aha moment, but it's the wrong way to think about literature, instrumentalizing literature in this very one-to-one relation with acknowledgement and action. It's a lie we tell ourselves as well about the ongoing capacity for human beings to have double consciousness, to simultaneously feel emotion, to identify with the character in a novel and also quite easily to take up a gun and to shoot at members of that character's community. That happens all the time. The example that Barghouti gave when I heard him talk at that time was of the Said Barenboim Orchestra, which was the East West Divan. It was an Israeli-Palestinian orchestra. Said is very criticized for it because it essentially was a kind of normalizing outfit, what they call normalization. He gave the example of an interview with an Israeli violin player, a young guy. He talked very happily about his participation in the orchestra, but he had no problem swapping his violin for a gun. It had had no effect on him. He may have realized that Palestinians were human beings, but hadn't stopped him from shooting them. There are different forces at play. I think it helps to put less pressure on individual recognition as it were, then on larger structures as well, if that makes sense.

DN: It does. Well, this question of influencing others, and I would also say being influenced by others, of perhaps even defining the notion of self inextricably in a relational way to otherness, I feel like it's at the core of the open questions I try to hold space for on the show. I wanted to talk about what the role your speech has played in my own life in this regard. But it requires me sharing an anecdote, if you'll indulge me. As far as I know, there aren't literary awards for literary podcasters. It came as a surprise to me to be given one from another field entirely, from what's called The International Forum for Psychoanalytic Education. In anticipation of going to their conference and both being interviewed before an audience and then giving a speech at the awards banquet, the award forced me to think hard about what it was I did and also how I framed it, but it also presented a challenge in so far as it prompted me to think of it in relation to psychoanalysis, which is something I know very little about. I've gone to therapy, most of my adult life, but never to an analyst. I was aware that my image of psychoanalysis was likely a century outdated, that the field had surely evolved and changed over that time, even if the stereotype hadn't, I just didn't know how it had. I didn't know where this particular group of psychoanalysts fell within the larger community. I suspected they weren't normative or centrist within it given my invitation as an awardee. I was happy to find that they were—if not rogue analysts—certainly at the margins interrogating its borders. I think of Hala Alyan, the Palestinian poet and psychologist, who looks to break out of the mode in psychotherapy of centering the individual as such and the individual subjective interior experience, which I feel like you were just nodding to and what you're thinking about around making novels and looking more toward more collective modes. I think of our thoughts when I think of one of the other people I was honored alongside Dr. Francisco González who works with Latino immigrants in San Francisco and has developed the notion of community psychoanalysis and has written about psychic life at the intersection of the individual and the collective, about the ethics of place and what he calls “the gated communities in our minds.” I bring this all up because in figuring out how I was going to articulate my own work to this somewhat unknown audience, there were three things I used: My conversation with Naomi Klein about doppelgangers and projective identification, and the ways we construct narratives that reiterate and pass down trauma where we looked at this in relation to Jewish memory, identity, and history. My conversation with Pádraig Ó Tuama, the queer Irish theologian and poet about reconciliation work he did in Northern Ireland with Protestants and Catholics, based on an idea that people opposed to each other, if given the space to talk, will either air their grievances or tell a story that buttresses their own goodness or their own victimhood. Instead, he had them meet through a shared third space, The Book of Ruth, a book of the Hebrew Bible from both of their traditions that, nevertheless, most Christians don't know very well, but also one that doesn't have divine intervention in it, so something an atheist could feel welcome in, and which is about taking risks across borders and about mutual aid on behalf of strangers and despised peoples in a way that troubles both the sense of self and a sense of peoplehood. This approach has really influenced my notion of how to write narratives that are porous or porous to counter-narratives and as a framing for conversations on the show, I spoke about both of these when interviewed, but from my acceptance speech, I talked about the end of your speech, something I was nervous about doing, not knowing how it would be received, sharing a table with people who have been teaching Freud for 30 or 40 years. While it was a very diverse group of people overall, there were, given the profession and its origin, a preponderance of fellow Jews, Jews of unknown political persuasion, and also unknown connections to victims of the Hamas attack which had happened less than a month before. But it was received incredibly well. You're looking at Edward Said's, I would call loving psychoanalysis of Freud, lying Freud down on the couch and looking at why he might believe that Moses, contrary to both Bible scholars and Egyptologists, was not only not a Hebrew, but an Egyptian, and that the monotheism he introduces came from a specific pharaoh. What you unpack here feels very close to my own sensibility or aspirational desire of how to move through the world. I was hoping you could talk just a little about this part of the speech, about Said and Freud and Moses in relation to where you're headed in Recognizing the Stranger.

IH: Thanks, David. That's great that you did that. [laughs] I went down well.

DN: Me too. [laughter]

IH: Yeah, it's quite an amazing lecture, Freud and the non-European. It's very much Said's own late style, this lecture. Freud was basically an anti-Zionist. This was concealed actually by the state of Israel. There was a letter he wrote to one of the early Zionist leaders saying, "This is a terrible idea." This letter was written in Hebrew saying, "No foreigners should see this." It was concealed in the Israeli official library, National Library. They didn't want to admit that Freud, among others, Walter Benjamin as well, these people were very concerned about the Zionist project and its implications after the disasters of the Second World War and the Holocaust. I guess it's difficult at this time to talk about loving strangers beyond the stranger being the Palestinian, because at the moment the Palestinian is the most abject, the most denied, the most dehumanized, and so the stranger now is the Palestinian. There is a beautiful book, you may know it, by Etel Adnan called Sitt Marie Rose, which she wrote during the first phase of the Lebanese civil war about the killing of a Syrian Christian woman called Marie Rose, who was helping the Palestinians. She was killed by a Phalangist militia, the Christian fascists. It's a very polemical text. It's a kind of extraordinarily polemical text. I taught it in Palestine one summer and the students loved it. [laughs] I think they loved what she said. Adnan puts all these words into the mouth of Sitt Marie Rose, she tells to her attackers and she lectures them on their clinging to the tribe and the vital importance of loving the stranger. She positions love, she describes love as a force like electricity, which can be destructive or it can be creative, like the sun. The stranger in the text is the Palestinian, of course. But I guess what I wanted to gesture out there was the ways in which an anti-Zionist ethic is one that ultimately recognizes everyone and we have to be quite careful about not allowing the humanist language that Said uses to disregard the immediate pressing urgency of Palestinian liberation, but that ultimately it is about everyone. It is about all strangers, whoever that stranger is. It is about the possibility always of being wrong.

DN: Well, I feel like you're raising of a discomfort about the stranger being someone other than a Palestinian at this moment speaks to this tension between the conclusion of the original speech and then the afterword, which is written after October 7th, one delivered just before one written afterwards. If you'll indulge me, my next question is going to nevertheless be about the end of the speech. Then the one after is going to be about my own anxieties, about speaking about it this way, and what you do in the afterword around that. I want to read several of the lines from that section of the speech that stuck with me in talking about how Freud dissenters the conscious will by excavating that which we do not understand about our own selves. You say, “Acknowledging the alterity in our minds and hearts is to reconcile ourselves to ambivalence, strangeness, and internal disunity,” and "The otherness that comes at you from the world has been inside you all along.” When thinking of Moses in Freud's interpretation of him, and Said's subsequent meditation on the great stranger at the heart of the Jewish story, and subsequently, Freud's refusal to submit to ethnonationalism by searching through an alternate archaeology for origins that destabilize rather than stabilize, you say, "Said reverses the scene of recognition. Rather than recognizing the stranger as familiar and bringing the story to a close, Said asks us to recognize the familiar as stranger. He gestures at a way to dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity.” This speaks really deeply to me as a person, but also as a Jewish person. To tie this back to The Book of Ruth, but not in a Protestant or Catholic context, but in a Jewish context, it's interesting that the book is about taking risks across borders, but also borders of identity where someone from the absolute most hated community risks are taken on their behalf, that this person from the most othered community then becomes the matrilineal line that produces King David, one of the most quintessentially Jewish figures since he represents the height of the Israelite kingdom. It's interesting to me also that this book is read on the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, the holiday commemorating Moses receiving the revelation on Sinai, because Moses and David being what you would think of as the most emblematically Jewish figures, or maybe perhaps the figures that would be put forth as a fixed identity of what a people are, Pádraig talks about, when we talked, he talked about the four prophetic theories in the Hebrew Bible of why the Jews had been punished with Babylonian exile and captivity. He speculates that The Book of Ruth was written as a counterbalance or an antidote or an opposition to one of those theories, that it was because Jerusalem needed to be ethnically pure and that people with wives from other communities or mixed heritage children should be kicked out. I wondered if this is why The Book of Ruth, at the definitional moment of what Judaism is when Moses comes down with the tablets, if we read it as a warning against the dangers of fixed identity, or in your words, as a way to dismantle the consoling fictions of a fixed identity, so much so that in your speech, whereas Said nods toward the irredeemably insider, outsider, unhoused position of Jews, you suggest he is now just as much describing himself, and that Palestinianism for him was just this very thing, an ethical position of never feeling too at home. I understand the awkwardness of bringing this all up in this way now, but I wondered if you could speak into, or if this sparks any thoughts for you, either in concert with Said or maybe oblique or in a countercurrent to Said.

IH: Yeah, I mean, I guess it just requires reiterating again the difference between Jewishness and Zionism and that Zionism seeks to fix Jewishness within the state of Israel and the structure of that state. The apartheid structure itself is one that seeks to fix identity. When people complain that Palestinians refer to the Israelis as the Jews, which is what they say, it's hard to argue that given that it says on their ID cards, it defines them as Jews, you're a Jew or you're a Christian or Muslim, you don't have a national identity if you're not a Jew. I think that it's about resting those things and refusing that conflation that the state insists upon and that increasingly American universities are insisting on and to fight that, I think is really, really important. That fight is being waged and is to be waged by Jewish people, which they are doing valiantly. That's why I think that that's the important thing there to allow us to engage with those ideas without that discomfort of saying, “Well, at the moment, who is the belligerent and who is the massacred?” But again, it returns to how we started with the moment of time and timeliness and where we are in the story. I guess we've now fallen into this moment in the story where we can't help it, there are certain things that press upon us with regard to an ongoing genocide, where the official number, say 40,000 people have been massacred, but it's likely to be much, much higher. Estimates are as high as over 100,000 up to a quarter of a million. This is beyond. I love what you've said, and at the same time, it's hard to prioritize that in the face of this extraordinary violence, which is unlike anything we've seen actually. This is five times the Hiroshima bomb has been dropped on this population. I think that's maybe why my afterword, it feels so palpably different just because I still believe those things and I still love Said and I love his reading of Freud and I love his reading of Jewishness and the ways in which that can also be a kind of Palestinianism that these things can all be sort of ethical, intellectual positions, which require a nonalignment that require a kind of remaining aloof from the group. But Said himself moved between alignment with the group, with the party, and being aloof. Now is a moment where we all have to fight.

DN: Yeah. Well, that's exactly the uneasiness I'm feeling and even bringing up that last question. I want to stay in the uneasiness a little longer with you if you're good with that. Because much like there are dangers and pitfalls, I think, and irresolvable mysteries when speaking of language in relation to action, and what one or the other can and can't do, it feels like there's something similar with this psychoanalytic dynamic of Recognizing the Stranger, similar pitfalls and risks. Thinking of the Palestinian campaign for the academic and cultural boycott of Israel and their guidelines about what should or shouldn't be considered boycottable, they do think cultural activities that they call normalization projects, ones that are based on a false premise of symmetry between the two sides, activities bringing both sides together to overcome barriers, but without addressing root causes and requirements of justice, that these activities are boycottable. Fargo in another essay of his, using Alex V. Green's term of what he calls the having conversations industrial complex, says, "The fetishization of conversation and its constituent parts, dialogue and listening, is a colonial tool to obfuscate, suppress, and limit the material demands of colonized and racialized peoples, foreclosing any revolutionary gestures or possibilities.” Or as Darwish said in Fady Joudah's translation, “No / victim kills another, / there’s in the story / a victim and a killer.” I also think of your review in Jewish Currents of the reissue of Anton Shammas's classic Arabesques, which is about his own family's dispossession, but which he wrote in Hebrew, and where you say, “He acknowledges the trope of the good Arab who speaks Hebrew well and earns conditional inclusion in the Israeli state project, and risks fulfilling the trope as he tries to subvert it.” Much like I think both that words aren't actions and that words are powerful and that words threaten the powerful, I feel like these are real and vital points being raised about encountering the stranger, that the risk, particularly for the victim in that encounter, is the risk of further entrenching and normalizing that the dynamic one is meeting for in the first place. Yet at the same time, hated enemies meet all the time. The negotiations between The Irish Republican Army and the British were once unthinkable. I bring all this up because I wonder, well, I know that you share this anxiety around this meditation on Recognizing the Stranger and I know that you and Pádraig Ó Tuama are very aware of structural and power dynamics and are both coming from the place of the colonized, but I wondered if your post-October 7th afterword might be motivated by anxieties inherent to this question of otherness in Recognizing the Stranger, where the afterword opens not with the stranger within the familiar, but instead with your mother recognizing herself in the plight of fellow Palestinian women on TV by saying quite simply, “That is me,” which feels like, interestingly, there's this incredible tension, electrical tension between the way you end your speech and the way you open the afterword. I don't know if it's resolvable, it's certainly not reducible. But if we could speak to that gap a little more, that would be great.

IH: What has become increasingly clear, even more than I was before, is, as we said before, the question of working in collectivities rather than as individuals. I think this is where, for me, one of the discursive risks in the US context lies, which is the pressure on the individual to recognize and to be recognized and to speak. When you brought up the issue of the boycott, for example, or of normalization efforts, for instance, someone rang me the other day and asked me, “I've had an offer from an Israeli publisher, should I go with it? What do you think?” I said, “I'll tell you my opinion, and you can take it or leave it. My opinion, as you would imagine, is no. These are the reasons why.” Even if you speak to some good Israeli soul who either already is an anti-Zionist or is on their way there and you participate in that journey or you humanize Arabs and so on, just quantitatively, the amount of people you persuade, it pales in comparison to the group power of us standing together and saying no, that has a much greater power than that individual conversation. That's not to say that that individual conversation wouldn't have value or maybe it would be effective. It's about a kind of a sacrifice, actually, it's sacrificing that, which might be wonderful. It might have other really good effects, but it's the principle when you're part of a movement that says it's not all about you, it's about heeding the call of Palestinian civil society and sometimes doing the right thing is not what you want to do. Sometimes it feels like, “Oh, but it's not perfect.” But that's part of it. That's part of it. You don't necessarily want to do it, but you do it because you're with everyone else and you're participating in something larger than just you, than just the individual. There's obviously some dialectic going on there. That's the principle of the boycott movement, which is what's brought down the South African apartheid. It started in Ireland, these principles there. It is the main nonviolent resistance movement, which is vitally important. It's been criminalized and we need to support it as an act of free speech in itself. But of course, when I wrote that afterword, it is talking about one person looking at one person on a screen and both things are true at the same time. [laughs] There's also like human-human relation and I don't know, it's still complicated, of course. I mean, I don't know if I answered that adequately.

DN: You did. I love that you preserve the complication and even contradiction in the speech, but also in the speech in relation to the afterword. In your meditation on the Greek word “epiphany” in relation to the short story form in the speech, you talk about it having three meanings: the manifestation of a deity, which is the Christian meaning of the word most commonly seen, but also the appearance of the dawn and the appearance of an enemy army; the latter two suggest something appearing beyond the horizon, beyond the field of vision that become, as they appear, a revelation of light and threat, respectively. I bring this up in thinking of ways of address, both in art and in the world, ways that work against the normalization of the status quo. To me, the most unforgettable poetry collection this year is by the Palestinian American poet and translator Fady Joudah, a collection whose title isn't speakable, perhaps a pictogram, perhaps a bracketed ellipsis. But the reason it feels like it speaks both so deeply into and from the long middle of genocide, and yet also seems timeless, is related to this combination of threat and light, as many of these poems are addressed to what he calls his "enemy friend," which reminds me of how you describe the protagonist in Arabesques as having a fraught intimacy with his Jewish-Israeli counterpart. That Fady’s speaker chooses to move further into that fraught intimacy is what makes the poem so powerful to me. When you suggest in the speech that we become less human when we don't recognize the alterity in ourselves, there's a way that his poems suggest the outcome of this lack of recognition when the people are incapable of looking inward can be and is this very terror being rained down on his own people. I also think of the political prisoner, Walid Daqqa, who recently died in captivity. Last time you and I talked, he was still alive and you read from his letters for supporters of the show. I think of him when he says, “In the jailer’s quest for control, he looks into the prisoner’s mirror to see his hideous self. He is afraid of what he has done, and what the reflections of this mirror may do to his self-perception, and so he seeks to destroy it.” It feels like both the threat and light of Fady’s address, his approximation to his enemy friend, is by refusing to other his enemy by stepping forward instead. I feel like it forces the jailer to see that the enemy is actually inside. The threat is inside looking back from the mirror. In light of this and these questions of humanity, dehumanization, and projective identification, I wanted to return to what you alluded to at the very beginning, your own recognition scene in the afterword, where you quote from the film Exterminate All the Brutes, a quote that goes, “The idea of extermination lies no farther from the heart of humanism than Buchenwald lies from the Goethe House in Weimar.” The proximity of humanism to colonial violence and genocide is something you say you knew all along but did not want to know. Something that I feel like Daqqa and Joudah, and now you, I think, are trying to redirect back to its source.