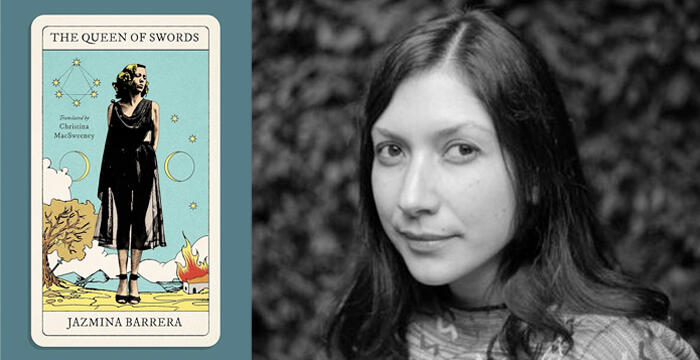

Jazmina Barrera : The Queen of Swords

Jorge Luis Borges called her the “Tolstoy of Mexico” and César Aira the “greatest novelist of the 20th century,” so why is it likely that you haven’t read or even heard of Elena Garro before now? And given that Garro was, like her fantastical stories, not beholden to the truth when accounting her own life, and given that her own life was, in its radical shifts and contradictions, so wildly resistant to comprehension, how does one present her now to the world? Jazmina Barrera may be the perfect writer to do so as her new Garro-centric book The Queen of Swords is as unconventional as her subject. Full of cats and revolution, Tarot and the CIA, conspiracy and embroidery, this anti-biographical love letter to another writer also becomes a portrait of Jazmina as well.

For the bonus audio archive Jazmina contributes a reading from Elena Garro’s story “When We Were Dogs,” in Christina MacSweeney’s translation. To learn how to subscribe to the bonus audio and the other potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter, head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you by Brick, a literary journal. Each issue is as purposely crafted as a good novel, such as John Irving. Juan Gabriel Vásquez calls Brick “an indispensable feature of my personal landscape and a place I visit to renew my pact with the written word.” Christina Sharpe declares Brick “a wonder.” An international literary magazine based in Toronto, Brick is beloved by writers and readers the world over. The masthead of each issue hosts these words from Rainer Maria Rilke as translated by E. E. Cummings: “Works of art are of an infinite loneliness and with nothing to be so little reached as with criticism. Only love can grasp and hold and fairly judge them.” It's this love that drives Brick to publish the most invigorating and challenging essays, interviews, translations, poems, and boundary-pushing fiction. Brick’s winter issue is available now featuring Lydia Davis, Cristina Rivera Garza, Madeleine Thien, Solvej Balle, Rinaldo Walcott, Diane Seuss, and many others. Visit brickmag.com to subscribe to the magazine or gift a subscription this holiday season. Print subscribers get free access to Brick’s complete digital archive with issues spanning nearly 50 years. As a bonus for Between the Covers podcast listeners, take $5 off any subscription with coupon code betweenthecovers. All fall I've been talking about a quartet of interviews that are focused on diving into the wreck of the archive and strategies for salvage and creation in relation to erasure, distortion, and more. Today’s is the fourth. It feels like if you were to listen to Olga Ravn, Diana Arterian, Robin Coste Lewis, and today's with Jazmina Barrera, you'll get a crash course that will show you very different projects with many different creative methodologies that are nevertheless in conversation with each other, and I think they all deepen each other. They also join many other kindred conversations, whether Dionne Brand about her book Salvage: Readings from the Wreck, Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat, Tyehimba Jess’s Olio, or recently Rickey Laurentiis’s Death of the First Idea. But today's conversation with Jazmina Barrera and her engagement with the Mexican writer Elena Garro has some unique elements among them all. For one, focusing on an author who herself bends the truth or creates mythologies about her own life. But even more so, the truths of her life don't come together and cohere into understanding in the traditional sense. So how do you honor a writer, a person, who escapes easy meaning and categorization? What strategies do you employ to try to orient yourself to someone who defies orientation? What strategies do you employ to honor the mythification within one's approach? The further we go into this interview, the more methodologies to honor Garro's life are revealed, and yet strangely, it becomes more and more an anti-biographical book at the same time. In the spirit of the way Garro herself wrote, and some of Jazmina’s attempts to engage with history and the archive remind me also of the conversation with Laynie Browne, who has many books that are books of homage—writing under the aura of another writer, working within the mode this other writer has created and finding yourself within it. Where the archive you are drawing on is as much within yourself as anywhere else. Because Jazmina's book is coming out at the same time as the first arrival of a story collection by Elena Garro in English, Jazmina for the bonus audio archive contributes a reading from Garro's story “The Day We Were Dogs.” This joins many other contributions and is only one of many things to choose from if you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. You can find out about all of them, all the benefits and rewards and resources at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today's episode with Jazmina Barrera.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest, writer and editor Jazmina Barrera, studied English literature at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City and earned a master's in creative writing in Spanish from New York University on a Fulbright scholarship. Her writing has appeared everywhere from El País to the Paris Review, Letras Libres to The New York Times. She's also the co-founder of and editor at the press Ediciones Antílope, who have published past Between the Covers guest Claudia Rankine's Citizen in Spanish, as well as translations of Rebecca Solnit, Terry Tempest Williams, and Rivka Galchen's Little Labors, co-translated by Jazmina and her partner, Alejandro Zambra. Her debut book, Cuerpo extraño, an essay collection, was awarded the Latin American Voices Prize in 2013. Four of her books have since been brought into English, all translated by the acclaimed translator Christina MacSweeney and published by Two Lines Press, a press committed to, in their words, publishing daring and original literature in translation in striking editions. The San Francisco Chronicle says about her book On Lighthouses: “On Lighthouses appears on the surface to be six poignant personal essays littered with intriguing references to lighthouses, their keepers and their myriad influences on literature and art throughout history. But what comes through is a dark and often obsessive meditation on what it feels like to squirrel yourself away from the world and embrace isolation in the name of pursuing a passion, something beyond just a good-natured study of shipwrecks and their saviors.” And Verónica Gerber Bicecci adds, “Like a bowerbird constructing its nest, Jazmina Barrera collects microhistories about the hypnotic, geometric light emitted by lighthouses; but when she finds and listens to these histories in the dark intervals, she is a bat hanging upside down in the tower of memory.” The Atlantic says of her book Línea nigra, an essay on pregnancy and earthquakes: “When interpreting pregnancy through art, no starting point is better than the musings of the Mexican writer Jazmina Barrera. To call Línea nigra a memoir would be reductive—it includes so many references to fine art, literature, and history that it functions almost as an anthology or a masterfully curated museum of child-rearing.” Heralded by past Between the Covers guest Julie Phillips and Fernanda Melchor, with starred reviews from everywhere, Línea nigra was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Autobiography and for the Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize, and was picked by both Kirkus and Vogue as one of the best books of 2022. The New York Times says of her debut novel, Cross-Stitch: “Needlework is often depicted as a peaceful activity: feminine, unthreatening, decorative. Yet in Jazmina Barrera’s Cross Stitch, embroidery is revealed to be as quietly brutal as young womanhood, despite the shroud of innocence society often places over both.” Which brings us to the reason we're talking today, the arrival of Jazmina's La reina de espadas, in English as The Queen of Swords, which, like all of Jazmina's books, transgresses boundaries. Ostensibly a biography of the Mexican writer Elena Garro, it also flirts with memoir—as Jazmina is a character in this book—and she herself says from within its pages that what we hold in our hands is rather a personal portrait. Alongside the release of The Queen of Swords, Two Lines Press is also releasing at the same time Jazmina's favorite book by Garro, The Week of Colors, brought into English for the first time by Megan McDowell, with an intro from past Between the Covers guest Álvaro Enrigue. Of Jazmina's latest Elena-Garro-centric meditation, The Queen of Swords, a book that was longlisted this year for the National Book Award, Eileen Myles says, “This neo-bio is a total pleasure. I’d never known Elena Garro and now I’m riveted by the entire morphing fact of her. Jazmina Barrera’s take is intimate and playful, and transgressive in the ways we generally get condemned to when considering a life, especially a literary and a female one. Here we splash dramatically, surrounded by Garro Barrera’s obsessions, toys, affairs, homes, animal friends, the works. It’s a joyous brainy blast and I’m intrigued and changed byThe Queen of Swords as a reader and a writer.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Jazmina Barrera.

Jazmina Barrera: Thank you so much, David. It's such a pleasure to be here.

DN: So I want to start with a question that you can't possibly answer comprehensively, but nevertheless, I want to put it at the beginning as a frame for our conversation, something to think back to as we explore Elena Garro and you in relationship to her. So, Borges called Elena Garro the Tolstoy of Mexico. César Aira called her the greatest novelist of the 20th century. As much as she disdained the term, she was the unheralded beginning of magical realism—or at least her and Rulfo probably—her work having been a big influence on Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. She appears in the work of Carlos Fuentes, Silvina Ocampo, and Octavio Paz. Álvaro Enrigue, in his introduction to The Week of Colors, suggests she might be the first writer to perceive the importance of Frida Kahlo independent of the all-encompassing persona of Diego Rivera. She was one of the most important Mexican playwrights with 16 critically acclaimed plays, and many of her works were adapted into films. Yet in preparing for today and looking for seminars and conversations to watch or listen to, I frequently came across ones like the one titled ¿Por qué nadie lee a Elena Garro? or “Why Doesn’t Anyone Read Elena Garro?” And you find many efforts out there to address and change this now—from books like Elena Garro y los rostros del poder to UNAM’s round tables in English explicitly aimed to elevate her from obscurity. Similarly, you say in The Queen of Swords itself that despite your six years of studying literature and writing, and working on a master’s degree, you had never read or been taught her work. You ask two questions, which I want to ask you. Why had it taken so long to find her? And why were her books so hard to find in Mexico? Perhaps we can start to answer this simply by talking about how you did find her and what effect she had on you as you first encountered her.

JB: So I was studying an MFA in creative writing in Spanish at NYU. There were teachers, wonderful teachers from many Spanish-speaking countries, including Lina Meruane, who's a wonderful Chilean writer. I was working with her in this novel that I never finished or published. There was this story in the novel: a woman and her daughter were running away from this powerful, frightening male figure, a father figure. When Lina read my work, she immediately told me, "You have to read Elena Garro. You have to read her because there's many things in here that are in conversation with her." And I had heard about her, of course. Especially, I would say, in the dramatic aspect of her work, I was in contact with many playwrights who mentioned her and who said to me that her plays were really influential, and still very famous in the theatre. But in my studies at UNAM, in my studies later on, I never read her. I didn't read her as I did many of her contemporaries, for example, in high school. Her books weren't easy to find. I actually found a couple of them in the NYU library. That's the first time I read her. I was mesmerized, but they didn't have any more books in the library. When I came back, I tried to find a couple of other books and couldn't. I didn't stop to wonder why until I was invited to write this book, which wasn't actually going to be this book, but a much shorter version of it. It took me a while after I started doing research to understand why was that? Her books being as good as many of her contemporaries, why weren't they taught to us in high school or in college? And I think there are many reasons. It's not an easy answer because her character was a difficult one. She still is a very polemic character, and I was reminded of that when I published this book. Of course, being married to Octavio Paz, such a powerful, influential, important man in Mexico, created problems for her and for her work to be read, understood, and cherished, as I think it should. Also, I think she got in trouble with a lot of people. She was a very feisty person. She had a very strong character. So there are many people still alive who are intimidated by her person. She was also persecuted by the government, by very powerful people. She was very frightened and even paranoid at times, I would say, with reason to be so. So she got really isolated. Then the story of her inheritance is also troublesome. Still to this day, there are trials and fights around her books. So I think all of these things put together create a context for her books to be unavailable and difficult to read, which is changing. In the past few years, her books have been republished and contemplated in a different light, and her work is being spread out in a much wider, from many different institutions, from the government, from publishing houses, from the academy. I think there is a push for her books to be studied now since a very young age, and I'm sure in a couple of years, this will be very different. I really hope so.

DN: I hope so too. You're part of a wonderful, if totally by chance, sequence of conversations on the show right now that I would characterize as feminist engagements with the archive and with erasure and silencing. So we had Olga Ravn from Denmark engaging with the 17th-century Danish witch trials, where all the primary sources are the voices of the male judges, and Robin Coste Lewis rescuing the Black figure from several millennia of art history that was forged in the pathology of the white imagination and its anti-Blackness, and Diana Arterian looking at Agrippina the Younger, an all but forgotten empress in Rome, who is usually now remembered not for her own accomplishments, including her three memoirs, but as the wife of Claudius, the brother of Caligula, and the mother of Nero. Ten years ago, a Spanish publisher who was re-releasing a 1982 novel of Garro's to mark the hundredth anniversary of her birth was condemned for something similar, where the cover advertised her as Octavio Paz's wife, the lover of Adolfo Bioy Casares, an inspiration to Gabriel García Márquez, and admired by Jorge Luis Borges, as if she needed to be re-presented and confirmed by a chorus of important men. Within your book, you say you are writing The Queen of Swords to do justice to Elena Garro on her own terms, but then you take it back and say that that is pretentious to say, that no, you are writing the book for yourself. I wanted you to maybe talk into or stay with us within this tension or friction regarding your own motivations to write this book, both for her and for you.

JB: Of course, I think it's a natural impulse, I would say, when you start to get familiar with this character and start to build a relationship with her. I started to build affection for her and to want to save her in a way. You know, she's a very frustrating character at times because you see all of her greatness or all of her wonderful imagination, sense of humor, and you see and you read all of these other forces outside of her and within her conspirating to bring her down. So I think it's only natural that at first I thought, "This is it, I'm going to bring her back. I'm going to save her from herself and from her destiny," [laughter] which is of course impossible and it's egocentric in a way because, as I mentioned, there are many people around her now trying to bring her work and life to a different light and to a different appreciation. And trying to be humble and being true to why I was writing this book, I thought, "Well, no, actually what I want to do is just understand her." That's the main goal. It's not an easy one because she's a really strange character and her life is full of mysteries, full of secrets, full of taboos, and classified archives. It's just a practically very difficult research to do, but it was enough challenge for me to keep going. I just wanted to understand, it's not even to redeem her or to justify her, just to understand her and to share that understanding as far as it was possible.

DN: Well, with these other recent episodes on the show that I think your book is in conversation with, one of the main questions is how to rescue and re-present a person and their work and their life from oblivion, especially when their own words don't survive, where the official record is only from sources that we should have skepticism around, sources that shouldn't be considered official history even though they are considered official history. But your challenges, I think, as you've already nodded to, are different. In this case, we have a wealth of material written by her, an abundance of material in her own words written by her hand, but both the work itself and her life itself, they don't cohere, they aren't stable. Cristina Rivera Garza called her books "books with a basement vault, or a fracture, or both. Nothing is what it seems with Garro; or else everything is something else." Not just the books—the way she tells her own life story is full of fabrications, which you explore. In fact, many people you encounter when you're working in the archives say she's mad or that she's the spy who went mad. Vilma Fuentes, in contrast to Garro, confused reality and fiction but wasn't mad. Yet even within her very political life, both her own politics and the way she's characterized by others politically seem full of irresolvable contradictions. In other words, she's uncategorizable, which is, I think, a great asset as a focus when you're telling a story about someone, but also, as you've said, a great challenge. So I was thinking, before we begin to talk about these things, I was hoping you could read the opening one-page chapter in Christina MacSweeney's translation called "A Life on the Run," which gives us a taste of this convoluted but also almost mythical history before her birth that she inherits and continues after her birth.

[Jazmina Barrera reads from The Queen of Swords]

DN: We've been listening to Jazmina Barrera read from The Queen of Swords. You make some really interesting and I think ultimately powerful choices in how to write a book engaging with a character like this. Even though you open the book, "The beginning, at least, is clear," that first page isn't so clear. [laughter] I mean, that's as clear as it gets, probably. So maybe it seems clear relative. Elena Garro is already on the run, escaping our understanding of who she is, as you say, even in the womb, before she is born. We even learn far later in the book that she lives in eighty-six different residences in the course of her life. One thing you do, I think, is brilliant, is that early on you say, "This whole book should be taken with a grain of salt, because even though I never met her, I've fallen in love with her. I love her in those small parts of her scattered here and there, in her truths and her lies, because there is no space for indifference when faced with the huge personality of a woman who was brave, vain, charismatic, egocentric, brilliant—all that and so much more." So from the beginning, because you declare your love, that you are not impartial but under her spell, you declare yourself in a way as the unreliable biographer of an unreliable writer. In a sense, you're mirroring her in this way, I think. But more than that, you say, "This is not a biography but a series of portraits." And it feels like, in a way, at least to me, that these portraits are of both of you, of her refracted through you and vice versa. I guess I wanted to hear a little bit about how love shapes the writing, but also how and why you don't consider it a biography, and how that shapes the writing.

JB: Yes, so there are several biographies about Elena Garro. Some of them are more from the academic point of view, some of them from the journalistic point of view, but they are very good and they have a lot of information. I didn't want to do that. I really had the idea of the portrait in mind. Well, my mother was a painter, so painting is always on my mind. When I think about a portrait, I always realize how you see the character, but you mostly see the idea of the character that is in the eyes of the painter. You miss the gestures of the hand, the perspective, the framework, the intention in there. It's a mirror, it's a mirror where you see both reflections. I really like that. I thought it was more honest in a way than how many biographies try to erase the narrator to present this idea of objectivity, of truthfulness, of authority. There's also this idea of the expert behind the biography. I had no intention of becoming an expert in Elena Garro because I think that's impossible, because I think that would take me a lifetime. I just wanted to have a dialogue with her, with her work, with her life. I thought that many of the books written about her tended to reduce her into a stereotype. Either they transformed her into a crazy person, this exotic, which she was in a way, but just reduce her to something impossible to understand, someone violent, someone not worth the while. Or they transformed her into this perfect victim, which she was not. I think even though she was a victim of a lot of violence from many aspects of either her personal life or the government, she also had a lot of agency. She was a very brave woman. She was a woman who was able to control certain things about her life and other people's lives. I think it's disrespectful to her to disregard that. I also didn't really like traditional biographies that much. I found them a bit boring. I thought in this intention of compounding everything, every single thing about a person's life, which I think many times have to do more with the biographer justifying his work, you know. "I know so much about this person. I'm going to tell you everything you need to know about this person." I mean, a life is such a long amount of time that it could take you a year to write a single day in a person's life. You have to leave things out. It's just the way it is. Not only that, but the way you put that information together doesn't necessarily have to be the chronological one day by day. So I thought it was interesting to explore how many other ways can we talk about a life? How about we forget about the chronological framework and we look at it through, let's say, numbers or colors or cats, [laughter] what would happened then? And I think that made sense in this case, particularly because Elena Garro always played with time in her books, with form, with genre. She never got comfortable in her writing and just stopped there. She always kept pushing the boundaries, exploring other ways of writing. She also had the most amazing sense of humor. That is one of the things that made me fall in love with her. I couldn't leave that out. So I tried to preserve that and to do honor to her in that way also by having some sense of humor here, which is something I think many biographies lack. So I found amazing examples of books like these. I don't know why, but many of them were French. I really, really liked this book by Marie Darrieussecq about Paula Modersohn-Becker, who was a painter. I also really liked Pascal Quignard's book about the painter La Tour. There is also this book by Nathalie Léger about Barbara Loden. I found this book so inspiring because they went well beyond the traditional form of a biography. They had all the freedom in the world to address these characters in different ways and to really create a dialogue, which I thought it was difficult not to do because once you get close to a life, as close as you get when you are writing a biography, there is a dialogue always in your head. You anticipate what this person would say, for example, or you imagine how they would react to one of your ideas. I thought that was so interesting. I just wanted to make that transparent.

DN: You've given a great talk called "Why Me? — Self-Translating: Exploring Identity in a Foreign Language," where you speak about translating Amina Cain's most recent book, A Horse at Night, and having trouble finding an adequate Spanish word to convey the English word "self." That "yo" translated as "I" is not the "self," that "ser" or "to be" is not the "self," that "yo misma" is not the "self." Also, how weird it is that in English, "I" is capitalized and that the self is presented in this language as an object or as a thing. About how when you were pregnant, you became obsessed with the uncanniness of self, of being two and one. About microchimerism, where genetically distinct material of the fetus is left behind in the mother and remains there. That with the Nahua people, who were part of Garro's life from a young age and whose cosmologies influence her work, in their cosmology, all beings have three selves. You end this talk in a beautiful way about how the miracle we all live for is the communion of selves. Sometimes we achieve it through motherhood or through sex or through science or through being in the wilderness. But it all makes me wonder if perhaps your series of portraits of Elena Garro, rather than a cohesive narrative, arise from a sense of a multiple uncapitalized multiplicity of selves. That perhaps Garro has left distinct material of her life in your body. That perhaps the goal of this book is to live in a way at the borderlands between you and her. I think of the way Eileen Myles referred to you in her blurb as "as one as Garro Barrera," as if you were one newly created being. But does this prompt any thoughts for you about selfhood or about the pursuit of otherness in this project, The Queen of Swords?

JB: Oh, so much. That is beautiful, David. Thank you. Definitely. I think that is one of the most liberating things for me about reading and writing, the possibility of transforming yourself while you are entering someone else's head, while you are hearing someone else's words. That they inhabit you, that they change you. Elena Garro was such a complex character. She lived through the whole 20th century almost. She lived through many, many important historical changes in Mexico and in the world, through historical events that directly impacted her life, from the Spanish Civil War to Mexico's '68 student movement to the Cold War in Europe or in the United States. All of these changed her life continuously. She, as you mentioned, lived in 86 places in her lifetime. She went from being a wild child in the state of Guerrero in Mexico to being a socialite in the highest cultural spheres of Mexico and France and Europe and having dinner with Picasso, and to running away from gunmen in Mexico, to hiding in small hotels in Spain with no food and not knowing where she was going to sleep the next day. You cannot reduce this woman to an easy depiction. It's too much. Her work is like that. You get novels, short stories, poetry, essays, memoirs. She wrote magical realism, realism. She wrote the saddest books and the funniest books. So you're right. I thought I can't just do one portrait of her. I need to do a series of portraits. I also need to leave space for the reader to create their own image of Elena Garro, to interpret all of these contradictions, all of these mysteries and silences in a way they want and can, because otherwise it wouldn't be true to her. While doing that, I realized, of course, this is an extreme case, but we are all like that in a way. We're all changing. We're all changing masks. We're all transforming ourselves according to what happens around us. This, I think, is so unstable. It's just how it is. But there's a freedom in that as well. I found it so liberating, the idea that you can, while doing research on her, this idea that you can be so many people at the same time and through your lifetime, it is liberating.

DN: Well, the main setting where we encounter you as a character in the book is in the archives at Princeton University. As a first step to talking about how you dramatize you as a character in pursuit of Garro within the book about her, we have a question for you from the author Brenda Navarro. Here's what three past guests of this show have to say about Brenda: Miriam Toews calls her a "brilliant new voice, eviscerating and propulsive." Yuri Herrera calls her an author who knows that behind all affection lies hidden danger. Fernanda Melchor calls her one of the best-kept secrets in Mexican literature. Her award-winning book Eating Ashes, called a masterpiece by El Mundo, arrives in English, translated by Megan McDowell, in January, a book of separation and migration and an exploration of dispossession and tenderness in the aftermath of violence. So here's a question for you from Brenda.

Brenda Navarro: Hi, Jazmina. I'm Brenda Navarro and I am delighted to greet you in Between the Covers. I love to ask you about your world with archives. Do you have a specific methodology? [inaudible] matters that cast you? Or is the documentation that leads the way? Congratulations on your work and a big, big kiss to you and David.

JB: Wonderful to hear Brenda here. I love it. She's such an admired writer for me and just a wonderful person. I don't know that I have a specific method for doing research in archives or just in general. I'm very intuitive in the process. I think that's just because I don't have proper training on it. [laughs] I'm not a researcher. So I just start with what I have in hand and then look for other sources. As Brenda says, sometimes just the archives, the documentation leads the way. So you go to something that takes you somewhere else, etc. Here, I mean, most of the information about Elena Garro has already been published, except for what is in that archive and what is in other archives, which are closed, which we won't have access to them until maybe 2030 or something like that. There are also archives that I couldn't even find where they were, for example, the Bioy Casares letters that she received from Elena Garro. I just couldn't find where they were. So I went to Princeton and more than looking for the information that was in that archive, I mean the content of the archives, I was really interested in the material aspects of it. I think that was what I found the most appealing and endearing—just these old papers with the stains of coffee and cat's pee on them and the doodles. [laughs] All of this tiny information, which I think many times is left out of the big biographies and the big studies, which are concentrated on the big facts of life, I think all of this tiny stuff gives you a lot of information about the personality, the daily life of someone. It's all so alive. I think that that was one of my favorite moments in the research of this book. Also one of the weirdest because I spent so many hours in this basement just reading papers and papers and looking at photographs. Then I went out of it at four o'clock without having eaten and just started to hallucinate her, just started seeing her in places and dreaming about her and having these images in my mind, these very real conversations with her because all of these papers are so alive. It felt like I was intruding into an intimate place, that I was spying on someone, on something. It was just an amazing experience.

DN: Well, I picked out a paragraph I was hoping we could hear that was also going to help with the question I want to ask you afterwards. This is a paragraph of you, I think early on in the archives.

JB: Yes.

[Jazmina Barrera reads from The Queen of Swords]

DN: So you've already spoken a little bit to the question I'm going to ask, but I'm going to ask it nevertheless. Several years ago, we ran into each other by chance on the streets of Portland during the book festival. Then I reached out to you after you went back home to ask you for recommendations for our trip coming up to Mexico City. I was hoping for ones that weren't obvious, rather more deep cuts as I've been going to Mexico City since I was a teenager in the 80s. You gave us such a great list of suggestions that were beloved places for you that we dedicated our entire trip to seeing the city through your eyes. Even though you and I didn't know each other, nevertheless, I felt like I was getting to know you in a special way without you there, and yet in a way you were there everywhere. I'm somehow reminded of this when thinking about you rupturing the limitations of time and space to find an intimacy with Garro. The reason why I bring it up is because the next time we come to Mexico City, you and Alejandro had my wife Lucy and I over for dinner. One thing I was struck by was, as you've already alluded to today, both of your deep engagements with French literature. You recommended to us Neige Sinno’s latest book, Sad Tiger, which was also like your book nominated for the National Book Award this year. He also had a lot of Perec, who, perhaps along with Calvino, is the most known and beloved member of the Oulipo movement. In the passage you just read, you use a word, "infra-ordinary," but without alerting the reader to its unusual origins. It's a word coined by Perec, where he says, "How should we take account of, question, describe what happens every day, and recurs every day: the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary, the background noise, the habitual." And he suggests in that same piece of writing, a piece called "Approaches to What?" that trains only begin to exist when they are derailed, when they're not doing what they're always doing. Alecia Beymer at the Poetry Foundation continues in a piece that she's writing about this essay by saying, "We recognize scandal as the pit explosion in the mines. What we forget or are unable and unwilling to see is that the truly marvelous and significant and scandalous thing may be the daily work in the coal mines." So given this employment of this word, "infra-ordinary," in The Queen of Swords, I wonder about its influence on your work and sensibility. If it has an influence beyond what you've already spoken to a little bit about today, looking at all these textures and marginalia within the work itself, but also curious if Perec more generally has an influence on your work, whether in this book specifically or more generally.

JB: Yes, I love this question. I think Perec's work is one of the... I mean, I don't remember when this happened, but there was a time when Alejandro and I counted how many books we have from the writers we had the most books, and I think Perec won. He's one of our favorite writers, and I think he has influenced everything in my writing from my idea of genre to my idea of aesthetic freedom to just the enjoyment of reading and writing, this delightful playfulness in his work. But also, for example, in what is the name of this book in English, the one, the building...

DN: Oh, is it Life: A User’s Manual?

JB: Yes, so that book is one of my favorite ones. As you might remember, this book where he tells the story of all of these apartments and the people in them through the objects in the apartments, and each object becomes this pretext to telling all of these other stories. So just paying attention to the things that surround us is, to me, one of the most interesting things in life. I would even say it's a political act nowadays when we don't know where so many of the objects around us come from. If we knew, maybe we would act differently, and I definitely wanted to do something about that in this book. As I was saying, I think most of the biographies just concentrate, as you said, on scandal, and especially with characters like this, it's big romances and the political scandals that you hear the most about. But I think in all of these aspects of the material life of Elena Garro, you get a lot of ideas of who she was. So I dedicate a chapter to her clothes, for example, because she really liked embroidery and textiles, and she had a huge appreciation for beauty everywhere around her in the objects of her life, and she would sometimes spend the little money she had in just buying beautiful curtains. It could be understood as something "bane" or something superficial, but I would say it could also be understood as a rebellion against money and capitalism. I was rereading a short story in The Week of Colors where she says something like, "The way I was educated was not to save money, but rather to appreciate the beauty and to spend it and to share it." There is also this weird chapter in her life where she doesn't have money, but she takes in a homeless person in her house and feeds them. It's like, yes, I think all of that is part of the same thing. There's also a chapter about her notebooks, for example. I think you can learn things about a person just by looking at the kind of notebooks that they choose, whether they like spiraled notebooks or just plain-colored ones, or you can learn things about them from the cigarettes they smoke, for example. There's another chapter about her cigarettes, and she got into all kinds of trouble while looking for cigarettes in the Civil War in Spain, for example. I thought these tiny things were windows into her life and her character, yes.

DN: I wanted to ask a quick question also about this community that forms. So you are at the archives, you're spending all day there, but then at the end of the day, you meet with other people who are also at the archives who, I don't know if it's coincidence or an uncanny coincidence or it's just the nature of what the archive is. But all of these people you gather with to reflect on what you've discovered or what you're looking for that you haven't discovered, they're all representing different people who are contemporaries of Garro in her time. So in a weird way, this is another mirroring, a contemporary mirroring of this historical moment, where you're all avatars of these other writers. I just wanted to hear a little bit more about that, about the community that you're making meaning or figuring out meaning with.

JB: It was wonderful. It was maybe like being in a gang of archaeologists. I don't know why I thought that it could be something like that, because you keep finding these tiny clues about all of these writers who were contemporary, and because the literary Spanish-speaking world was and still is small. Many of these writers were in contact with each other and they exchanged letters, and there was this sense of camaraderie, but also just the delight of gossip. [laughter] It was so exciting to be with other people who understood how incredible these findings were because in my daily life around me, there aren't many people interested in the letters Elena Garro exchanged with, I don't know, Pepe [inaudible]. But there were people there who understood and who were like, "Oh, you have to look at these and have you seen these?" And "I found these," and they were sharing their excitement too. It was just such fun. I mean, the place was very beautiful as well. Of course, these were much more experienced researchers who knew what they were doing, so also they shared tips with me. Yes, it was an amazing experience.

DN: I intentionally wanted to wait a while before introducing the towering overshadowing figures in Elena’s life, most notably her husband, Octavio Paz, who doesn't simply overshadow her by chance, but also seemingly by design. I have to say, he comes across both in his own words and in his actions as an utter monster to me. We have a question for you from another in relationship to this. But before I play it, I wanted to preface his question with some context for the question for people who haven't read the book of some of what we encounter of Paz in The Queen of Swords. At one point in the book, you share with us Octavio Paz's letters to Elena, eight of which contain death threats during his courtship of her. Ones that include, "Obey me, adore me, stop studying or pursuing art." And, "I look at your portrait and don't know what to do, whether to love you or to kill you." And, "Maybe you don't deserve anything, not my rage, but perhaps a bullet, something that will annihilate you." And "I understand your situation. You don't understand mine. You must obey me automatically without thinking or I'll kill you. Don't be pigheaded." Sadly, and yet somehow not surprisingly, we only have Paz's letters in this correspondence. He calls her his divine little girl, an insolent kid, the goddess formed of tears and semen. Their marriage is an abduction because she's legally underage. She describes her wedding night as a rape. She flees home to her parents, but he threatens to have her father deported if she doesn't return, which she does, but considering suicide along the way, which is her first of many attempts. He prohibits her from writing poetry, which she had to do on the sly. He makes her burn her poems, or he rewrites them and claims them as his own. When they are in Berkeley for his Guggenheim Fellowship, he refuses to let her study at the university so she works as a maid. You note that the things he most reproaches her for, her intelligence, her skepticism, and her irony are her greatest literary tools. All of what I just said in this one or two minutes only scratches the surface of Paz in this book. But in the aura of this towering figure, we have a series of interrelated questions for you from the writer Francisco Goldman, whose last book, Monkey Boy, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and winner of the American Book Award, and was described by Anthony Domestico for Commonweal in this way: “For Goldman, the autobiographical novel isn't the last puff of a dying genre but a form through which to consider the competing moral and aesthetic demands of the real and the imagined. Monkey Boy is a fascinating hybrid, tightly, almost symmetrically structured, concerned from beginning to end with the possibility and transformative power of love. Monkey Boy doesn't jettison fiction for nonfiction, the artificial for the real, but considers the truths of both. The novel is dead, long live the novel.” So here's a question for you from Francisco.

Francisco Goldman: Hola, querida Jazmina, aquí está mi pregunta. The Octavio Paz we learn about here in your beautiful book was a monster. We know Carlos Fuentes could be too, but why do they still intimidate people? You write humorously, but not only that, that now you feel so attached to Elena Garro, you feel afraid too. Why? How has Mexico changed? Is an Octavio Paz conceivable among your contemporaries? I wondered if your fiction-writer self were to try to imagine the letter you wish Elena Garro would have written to Paz, what that letter would have been like. Then I realized, in some ways, your book is that letter. Is that true in a sense? Elena Garro compared writing to stitching and embroidery, and Paz even tried to prohibit her from doing that. Can you say a little bit more about that? Do you and Elena Garro share the aesthetic?

JB: Hi Frank. [laughter] I’m imagining my luck that one of my favorite writers is a dear friend and lives next door. [laughter] Yes, so this has been, I think, one of the hardest things about publishing this book, just realizing how strongly Octavio Paz still looms over the Mexican cultural scene. I knew it, of course, but it's been quite something just to experience it. I mean, these people died not that many years ago, so there are still relatives around, there are still students of them around, family members around, and they are still making money in a way. There are still many institutions with their names, there are still funds that come from the money they made, they are still paying the salaries of people here. So I think it's understandable that many get upset when you “criticize” them. I didn't necessarily think that's what I'm doing, I was very reluctant to pass judgment in this book, or at least without noticing it, without making it explicit that I was passing a judgment. I wanted for the readers to be able to make their own minds about this relationship. I just wanted to present the evidence I found, which is eloquent enough, I would say. There were many people mad at this book either because I was too critical of Elena Garro or not critical enough, or because I was too critical of Octavio Paz. No one said I wasn't critical enough, actually. [laughter]

DN: It's true that you don't need to provide judgment or commentary, I mean his words on their own condemn him.

JB: I think so. Yeah, I agree that it's terrible. What I found was awful, such a huge amount of violence. It was difficult for me—I mention that in the book—to understand how much this violence was the average amount in that time. Was this just the prevailing attitude of men towards women, or was this a particular case, which I think it's both. I think this was in the air and he was a special case, and their relationship was a special case. Still I think that in my generation there is distance enough from these characters that many people are starting to come up to them without feeling that it is a personal threat to them or to someone else to criticize them or to question them. So I think this is just a matter of time that we will get to see these characters without all of these passions arising around them. I think it will happen and I think many people are realizing who they are. I mean, I also got all kinds of reactions, many people who really liked the book, who were friends of Elena Garro. But what I found most interesting was a couple of people who were Octavio Paz's pupils, who were their protégés, who really loved him, who came up to me and said, “I can't believe this. I didn't know this. I didn't even want to know this,” which I think says a lot about the attitude of people around here. Yeah, I think this is, of course, happening all over the world with the rise of feminism and Me Too and all of these movements that start to point out these different kinds of violence in the past and in the present. I think it's a very interesting question. What do we do with these monsters? What do we do with these complex characters? Even Elena Garro herself, who wasn't a saint, who still had many things that we can criticize about her. How do we read them? Or do we stop reading them? Or can we love them even though they have all of these flaws, despite them? And are we still allowed to talk about them or teach them? I don't think there's an answer for them. I think each case is a specific case...

DN: And for each specific reader, I think.

JB: Yeah, someone who is able to hold both thoughts at the same time and say, “This is a wonderful piece of art and this was a horrible person.” And someone who maybe is not, who says, “I really cannot appreciate this thing right now because this other idea is hurting me or is making me sick or something.” I think it's all valid. Yes. And Frank had many other questions, but I think I forgot them. [laughter]

DN: Well, I want to spend some more time with his questions, actually. So I'll extend his questions on his behalf. Because I love how Francisco asks you what you imagine Garro’s letters to Paz would have said. But also whether you see the book as the answer. I'm curious about that. I'm also grateful he brought up embroidery and stitching because I want to talk about the formal qualities of your work, which I do think also have a political underpinning to them, a feminist underpinning to them. In the broadest strokes, I feel like I see a pattern in how you construct your books, even when the topics differ greatly. In On Lighthouses and in Línea Nigra: An Essay on Pregnancy and Earthquakes, and in this new book, The Queen of Swords, and all three, you weave or braid or stitch together many things and also many outside voices. And in doing so, I feel like you not only weave them, you leave the stitching visible, perhaps like the línea nigra itself, the dark line that some women get on their abdomen during pregnancy. Your novel Cross-Stitch also has two origins, one as a novel that was close to your own lived experience, and also a short essay written about embroidery, where you say in one interview, “I then decided to embroider the fragments of the essay with the fragments of the novel and make something like a quilt out of all of this.” That seems similar to what you say in The Queen of Swords, when you say, “This is not a biography, it's scarcely a notebook. It is a collection of stories, ideas, facts, and cats.” Embroidery is a feminized activity that, unlike with Garro, who was prohibited from doing it by her overlord husband, was sometimes an obligatory activity for a woman/wife. You’ve talked about how women, when they weren't encouraged to write or even to read, would find liminal activities—recipes, diaries, letter writing, embroidery—that could become literature-adjacent sometimes, or even a way for women to pass messages to each other through clothing or through objects. Mila, the character in Cross-Stitch, who herself has written a book on needlecraft, says, speaking of cross-stitches, "The stitches are figures, crosses that seem to be separate, but are in fact a chain and a single thread. One thing." I feel like you do this across your books, which have you in them, and yet we discover you through the voices of other people, whether that's Ursula Le Guin or Elena Garro or Robert Louis Stevenson. I view some of the choices you make in The Queen of Swords in this light, rightly or wrongly. For instance, you don't use endnotes or footnotes, but instead the margins of the book are alive and active with citations from various books of Garro’s, making your sources ever-present. I even think of how you tour for the book with your translator, which I feel like makes it clear when your work is in another person's words. Often I bring up on the show—probably too often—I bring up Christina Rivera Garza’s phrase of “returning writing to its plural origins.” But I feel like you're a particularly supreme example of this. Garro says, “My technique for writing is sewing. If I didn't embroider, I couldn't write.” I guess I wonder if you could speak to this. Am I reading too much into what I notice is perhaps connections between your books formally and this embroidery or stitching motion that Francisco is also asking about?

JB: No, I think you're absolutely right. I think it has become something of an aesthetic in my case. I haven't embroidered since I was a child. I'm not wonderful at it, but I do enjoy it a lot. I've been also very drawn to fragments in literature since my first book. I always find different answers as to why I am using the fragments in each particular book. For example, in On Lighthouses I imagined a cabinet of curiosity and I had a very visual idea of how the fragments went along with each other. In Línea Nigra I thought that the fragments had something to do with the rhythm of the first month of motherhood and interruptions. It was also just a book that wanted to homage many other motherhood books who had that same form, small fragments. In Cross Stitch, I was looking into all of these different ways in which embroidery had, on the one hand, been a way of oppression for women and part of all of this ideology that wanted to enclose women in the house and in domestic activities. This was, after all, a mandatory thing to learn for women—to embroider—but also how women subverted that oppression and found ways of expressing and creating through embroidery that were very liberating. The form just came naturally out of this. And then Elena Garro mentions—I don't remember, did you just read that phrase or not—but she does say somewhere that embroidering for her is a method of writing, is her method for writing, which I find beautiful because I've had that experience myself, that having a manual activity, either working in the garden or embroidering or cooking or washing the dishes, is in many of these activities for me where ideas come to my mind, these ideas that then I get to write about. But there is something in the way that the hand, I don't know, creates space and time and silence for ideas to appear. I also think that you're right, that there is this beautiful thing about embroidery that the patterns and the stitches are shared amongst women freely. You pass them from one generation to another, you share them with your friends, with the women who are embroidering close to you. There is not this sense of ownership that you do get in many of the more traditionally masculine Arts, with a capital A. This preoccupation with originality and with copyright. There is something very beautiful in the fact that you don't know where these stitches come from. You can trace them sometimes back to Egypt. You can find them in so many different countries at so many different times in the history of humanity. It doesn't matter. They keep renovating themselves, they keep changing and going backwards and just creating beauty and working as a way of expression. I think there are many books to me that feel like that, that are very generous in the way they share other voices, other ideas, other books, other genres, other disciplines, even the way they integrate music or gardening. Writing for me has always been a way of sharing. So I think that's why my books are always filled with quotations. I always work really hard so that they don't feel pedantic or snob or just overwhelming. When I find something that is exciting to me, writing is my way of just sharing that with the people I love, but just with anyone who will listen.

DN: I love that your exploration of Elena becomes an exploration of you, but also that you discover, I think, things about you that you share with her, like this embroidery–writing connection. But you also literally, thinking of this notion of a cross stitch being a single thread, you actually discover repeatedly your own family and their history intersecting with the histories you're exploring of Garro and Paz as you explore the archives. I mean, obviously, you're not going to talk about everything that you discover of the ways your family’s involved, but it's not insignificant, the things that you are finding of your own family members, your grandparents, in relationship to these figures. Maybe there's one or two of them you'd want to share with us about things that you found.

JB: Sure. The first thing I found I think was this mention of my great-grandfather in one of Octavio Paz's letters. I have this great-grandfather who was a Maya archaeologist in Yucatán, and he was working in a museum where Octavio Paz was working at the time, and they become friends. That was just a curiosity to me. It was like, wow, this was really a small world. The middle class in Mexico has always been a small world, but I think maybe in the past it was even smaller. Then these other things started to appear, this picture of a different great-grandfather and my great-grandmother with Elena and Octavio Paz having dinner somewhere in Cuba, I think. They are talking to each other. It's like, I just wanted to know what they were saying. Did they like each other? Did they not? And then the final thread that I think connects my family to Elena Garro is the ’68 student movement, where my grandfather had to go searching for my grandmother who was in the middle of the shooting and survived miraculously. The way that affected my family—because my grandfather had to leave the country after that—it's a very dark period of Elena Garro. It's a before and after for her, actually, because she came from a time where she had been very active in defending peasants in Mexico who were having their lands taken from them and she was helping them. She became really political at the time and she came close to this movement and at the same time rejected it and got somewhat caught up in between. She betrayed them, but she was also persecuted by the government after that and even kidnapped. It's so confusing. But after that she had to leave the country and she was away from it for about 20 years and she had a really rough time for a while there. She was living in tiny hotels with no money and just really depressed and scared. So it was very important for me to understand that particular time. I mean, for the sake of the book, but also in a personal way because I had this chapter in my family that came from that period that I also wanted to understand. I don't know what it did to me to find all of these coincidences with my family and Elena Garro. I think it just added up to all of this ghostly aspect of writing this book because there was, as I mentioned in the Princeton chapter, I started to imagine her and to see her in my dreams and then suddenly she was there just like having dinner with the ghosts of my family and it just started to become really close to me and to become, yes, more intimate, more personal.

DN: Well, let's spend a little more time now with her politics, which is the most maddening part of trying to understand her life, particularly the exile, which it's clear that you don't entirely grasp it. I don't grasp it as a reader. You don't grasp it as someone who knows far more than me. Álvaro Enrigue says in the introduction to the story collection The Week of Colors that she was exiled as “a traitor to the left or as a leftist betrayed by the right,” that she was the friend of brutal oppressors and brutally oppressed. You describe her stories in a more general way as “stories that denounce violence against women, that describe the child's mind with astonishing levels of understanding, that speak openly of the perversity of the government, of racism, of classism, and the struggles and resistance of Indigenous peoples.” But her political life in the world seems almost impossible to parse in contrast to those themes in her stories. For instance, she was an anti-fascist in Spain in her 20s, a supporter of Trotsky, had an affinity for communism, but then decades later in her memoir she opens the book with the line “I've never heard of Karl Marx,” and she was mainly known as an anti-communist with a hatred for Lenin. Yet she was also an anti-capitalist who believed in the Mexican Revolution and also in land redistribution. She even goes to a wealthy farewell party for a writer with a group of campesinos seeking support against land theft and together they puncture the tires on all the expensive cars. Yet you say her characters often seem enamored with monarchies. In the ’60s, she writes against the student uprising while also being accused of helping to start it. She's surveilled by the CIA and by Mexico, and she says she meets Lee Harvey Oswald in Mexico City at an event full of Cuban diplomats and Mexican leftists who had expressed hope during that party that Kennedy would be assassinated. The CIA thinks she's nuts. Communists want her dead. There are threats that her house is going to be blown up. Ultimately, rumors she's going to be assassinated. So as you mentioned, she leaves for decades in exile. I mean, I don't know if there's anything more to say about this. I love that you don't try to make sense of it, to reduce it to something with a through line. But I guess can you speak a little more to how you orient yourself as a writer, as a portraitist, to the way she is perceived politically in relation to her own politics on her own terms.

JB: Yes, I just gave up at some point. [laughter] Because I thought it was me. I thought I wasn't understanding it. But then at some point I realized this is not understandable. I mean, there are just too many contradictions, too many ambivalences. I don't think she understood it herself. Or many of the people around them really knew what they were doing. They were sometimes just reacting to different interests at the time, or they were going with whatever more powerful people were telling them to do and changing their minds. I think it's a particularly difficult period to understand in Mexico's history, more so regarding her, [laughs] yeah, because she's such a maddening character in that regard. And then what was the question? [laughs]

DN: No, that was it. That was it. I mean, even though she has contradictions in regards to feminism also—that she didn't consider herself a feminist, that she was against abortion even though she had many abortions—it seems like her relationship to gender politics is perhaps the most cohesive of her political positions. You talk about how as a teenager she was in a school of 3,000 boys and seven girls, that in the ’40s she writes two magazine pieces called Lost Women 1 and 2 about a women's reformatory, where in order to write them she has herself imprisoned for several days. Her description of the punishments and tortures there ultimately gets the director fired. Given the threats of violence in her own life and family, it isn't surprising she writes about rape and femicide, how marriages deprive women of their identity. The thing that Paz does in The Queen of Swords that haunts me the most is around their daughter, Helena, who was often being taken care of by his mother and his stepfather. When she's four years old, she's raped by Paz's stepfather and gets gonorrhea. But once she's cured using genital cauterization at the time, Paz sends her back to live at his mother's house where she's raped again. Elena Garro and her daughter become lifelong companions as adults. I guess I'd love to hear more about her portrayal of women in her work, anything that comes to mind, any particular examples that stay with you, because you characterize her writing as feminist from your perspective in contrast to her own framing of it. Perhaps you could also speak a little bit to her and her daughter's contentious, but very enmeshed lives together as adults.

JB: Yes, yes, of course, I'm saying these stories are feminist from my point of view. In this time, I know that she wouldn't consider them that, or at least for a while she wouldn't. I think it's very evident the way she represents and criticizes violence against women, physical violence, rape, the particular violence that husbands exert against mothers while menacing them or using their daughters and sons to punish them. The violence that is learned from one generation to another and that haunts entire towns, femicide, all of these, they weren't easy topics at her time. I think she was extremely brave writing about them in the crude way she did. She's very literal in all of these stories. She also wrote about the way women weren't allowed to study, they weren't allowed to work. She denounced all of this in a really powerful way, I would say, because that is the other thing. She just wrote beautifully, I mean her prose was fantastic, she was very convincing in all of these topics. She used her own life many times as material for writing, so there are many characters that sound like her at times or she uses phrases from her journals and diaries. There are many scenes where you recognize her own life in there, but she also has all of these other women in her books. She has Indigenous women, peasant women, house-working women from the highest classes to the lowest ones. She really represents an entire diversity of women and they are all very complex characters. Most of them at least, I would say some of them are more simplistic, but she has many characters who are weak, but also revengeful, but also charismatic, all of these different aspects, which I think is a feminist way of portraying women who had been for such a long time reduced to stereotypes. So yes, I would definitely call her a feminist even though she didn't understand herself to be so. So for me, Helena Paz is the saddest character in this story. I think if there is someone who is actually a victim of the circumstances, it is her. I mean, as you mentioned, she suffered all kinds of violence since she was a small child. She got caught up in this horrible marriage. She was the daughter of a very young Elena Garro. I mean, I imagine myself having to deal with a violent husband and a small child and I'm sure it was very difficult. She suffered physical violence. She became addicted to alcohol and barbiturates. She was moved around all of these places where they were living. I don't think she had any stability at all. It is no wonder that she became such an unstable character. She clearly was very sensible and very intelligent, but just maybe when she was about to break away from her mother a little bit and start her own life, this 68 drama happens and she has to flee with her mother. Also, she had a lot of health issues, which prevented her from becoming truly independent. So her mother was always by her side, taking care of her. But I think as they grew more and more isolated, their relationship became more and more violent and sour. It is really, really sad to read about that time in their lives and the way they treated each other and the people around them. Yeah, I really suffer when I go to that part of her life.

DN: Yeah. Well, we have another question for you from someone else.

JB: [Laughs] I love this.

DN: I mean, Elena Garro not only writes sometimes fantastically, but as we've mentioned also sometimes fantastically about how she portrays the facts of her own life. But she is sort of a fantastical figure herself. As a child, she's an arsonist. She makes raids on the homes of her extended family. She invents a language that the nuns think of as heresy. She was too wild for all the labels, and yet it seems like she attracted all the labels. In light of that, we have a question from the poet Eileen Myles. They came on the show long ago now for their incredible book Afterglow: A Dog Memoir, which itself was described as wild and unruly. Chris Kraus said of it, "Ghostwritten in part by deceased pit bull Rosie, this ‘dog memoir’ explores—among other things—geometry, gender, mortality, evil, aging, and plaids. Myles makes new rules for what prose writing can be." Next year, Fonograf Editions is publishing their never-before-published 1978 collection Bird Watching, along with their first three collections as a new yet archival poetry volume. So here’s the question for you from Eileen Myles.

Eileen Myles: Hi, Jazmina. If you could spend some time with Elena Garro, and I wonder what time it would want to be, if you could spend two hours with her, or a day with her, or a weekend with her, or two weeks with her, so decide the time, what would you want to do? How would you like to spend that time with Elena Garro? I mean, it sounds like she was a tough character, so it's possible that you would absolutely not want to spend time with her. So obviously the answer could be no, but within your stretch of imagination, if you could, what would you do? Thank you.

JB: I love Eileen. I'm such a huge fan. [laughs]

DN: Me too.

JB: They're amazing. I love this question because they usually ask me, what would you ask her? But what would I do with her? I would be very scared to spend time with her, I have to admit that. [laughter] I mean, I wouldn't beat the chance, but it would be so intimidating. I think I'd love to go around her library with her and hear about what she loved to read, her thoughts on particular books, writers. I think I would just love to do that so much.

DN: Do you know of particular writers that she had an affinity for?

JB: Well, at the end, the Russians. She was just obsessed with the Russians, and I'd love to hear about that. She, of course, was very close to the Argentinian fantastical writers of her time, to Borges and Bioy Casares. I wouldn't say Silvina Ocampo, even though they are supposed to be enemies because they were both in love with the same man; their short stories have a lot of similarities to them. I really think someone should write something about that. [laughs] She loved the Spanish Golden Age. She liked the theatre of the Golden Age, the Renaissance theatre, the poets. She really liked the Greeks, classical literature. She was really critical of Mexican literature, her contemporaries, but she really liked Rulfo, for example. [Inaudible] was clearly a big influence. She really liked Octavio Paz’s poems, we have to say. Even at the end, when she hated him, she kept saying she admired him.

DN: Yeah. Well, I love that Francisco and Eileen’s questions both ask you to imagine. To imagine either what is written on the missing letters or to imagine spending time with Elena Garro to conjure something in your mind that is not knowable. Because there’s a whole delightful thread of this book that is not only about Garro’s interest in the occult, but how you yourself try to conjure or gain access to something about her through using divinatory practices. Garro is named after Helena Blavatsky, the founder of the Theosophical Society, and her middle name, Delfina, comes from the she-dragon that guards the oracle of Delphi. Tarot is a constant in her diaries of exile. At one point, when you’re feeling like your manuscript was incorrigible and beyond repair, you decide you want to read Elena Garro’s cards, but a friend tells you you can't read cards for her, but that they could read cards for you about her. Your questions for the tarot reader are, I think, a testament to Garro’s resistance to being known, that even deep into your project, knowing more than most people know about her, your questions to the cards are in some ways still the questions a beginner would have too. “Was she ever in love with Paz? Did she really befriend the head of the secret police or did she only use him for protection? Was she persecuted or was she paranoid?” And that you allow your book to stay, in your words, “beyond repair,” to not answer these questions but to ask them, to have the book remain a bit shaggy and stitched together, I feel is all to the book’s benefit, at least for me. But as you do tarot readings, palm readings, get her astrological chart read, and you throw the I Ching, when you reach an impossible-to-answer question—and there are so many with this figure—bringing in chance or inviting answers from outside of you, from outside of a human mind, can be revelatory in a different way. One person tells you they think Garro is the Queen of Swords, and you think instead that she’s the reversed Queen of Swords. But I wondered if you could talk about anything that comes to mind around this, the use of divination, which, on the one hand, you could just say simply is another way you're mirroring her in order to find the terms of your book that respect who she is. But on another level, you could see it as a way to confront dead ends when your pursuit is too linear. I'd love to hear anything you want to say about this part of the book, but also maybe you could orient us to the Queen of Swords and what it signifies for you as a tarot card.

JB: So, Elena Garro always had this magical aspect to her and her mind. As you mentioned, she comes from not only a religious but a somewhat esoteric family. She says that because of her closeness to different cosmologies and ways of understanding the world, her closeness to the Náhuas, to her father’s Buddhism, she understood time and reality in a different way. You can see that in her writing. As her life becomes more and more complicated, obscure, difficult, as there were more uncertainties to her daily life, she goes more and more to these divination techniques, to the I Ching, astrology, the tarot cards, always looking for answers about when she's going to get money, when she's going to be able to sleep somewhere. She even starts to read the cards for other people who come to her. This idea is almost like a stereotypical house of witches, these two women isolated from the world with their cats, so many cats, [laughter] and people coming to them for astrology and tarot readings. As you say, I came to a point in the writing of this book where there were still so many secrets, mysteries, contradictions, things that seemed impossible to understand, that I thought, well, if these were good enough for her in her time of despair, maybe they will be good enough for me too. I have to admit I'm a very skeptical person. My mother loved reading astrology books and I Ching and all of that, but I always thought of it as nothing but a game. But while I was doing it for this book, I came to appreciate it so much. I thought they were, yes, games, but games that really could connect you with information that maybe was inside of you, maybe was somewhere else and that you didn't have access to before. They were these fantastic mirrors that really did help me understand some things that I thought I couldn't understand. They gave me confidence in my instincts. Sometimes they helped me understand my unconscious better. They also just allowed me a different perspective on Elena Garro. Yes, it was one of the most fun parts of the book doing this. As you say, it was also an homage to her and to her approach to reality. Yes.

DN: Luna Miguel says in this book, “There’s a reason they called you the outcast queen. Or in the words of María Luisa Mendoza, the poorest queen. I’ve learned that you are the queen for reasons that have nothing to do with your work. Nobody has yet allowed you to be crowned as the best female writer in Mexico.” And you say that you call the book Queen of Swords to please Elena, who would have preferred a monarchy, who would have loved to be a queen, but instead ended up a witch. There are many things in your book that we didn’t explore today, the way she deeply and repeatedly engages with class for one, or her two-decade-long love affair with Bioy Casares for another, which in so many ways is the opposite of the one with her husband, his letters saying “I admire you, I respect you,” expressing a desire to hold her hands and her feet, even if, in my parenthetical about this, at the same time she’s worried that he’s going to seduce her daughter. But thinking of Bioy Casares’s wife, Silvina Ocampo, who you’ve mentioned, her and Garro make me think of when I was talking with Ursula Le Guin about gender and canon formation, that no matter how big someone seems at a given time—and I think we’ve established that many of the writers of the time had respect for Elena Garro—no matter how big someone seems at a given time, or how much they’re a part of the conversation, women can still slide to the edge and then off it and not be remembered. Ocampo was translated by Calvino into Italian and by William Carlos Williams into English, and yet is only now, like Garro, being recovered, reconsidered, and re-presented outside the shadow of her husband and their male contemporaries. Like the women translators doing this work on behalf of Ocampo, and you and Christina MacSweeney and Megan McDowell are working a sort of magic, also with time, and you’re reaching back and pulling forward, I just want to say something you said earlier, where you were being humble and downplaying the importance of what you’re doing. I don’t know if you’re rescuing her, but I still wonder. It seems incredibly important. I wonder if Hélène Cixous hadn’t championed Lispector decades ago in French—would the cascade have happened of recognition in English? Maybe it would have. I have no idea. But I wonder if it’s bigger than you think, this chain or stitching together of mainly women, women translators and writers, working a magic with time, reaching back, pulling forward. It also mirrors Garro’s own very unique relationship to time. And in the spirit of the way she inverts time—and there’s this beautiful way you mirror the inversion in the way you tell the story, and I’m not going to spoil it, but it’s really great. I want to end with where we should have begun. Instead of using the most important thing about her in your mind, if we were to have done it correctly, that should have been the frame for our entire discussion today, but instead I’m going to place the most important thing about Garro at the end as an open door at the end of our conversation. You say time is the true protagonist for her. The title of her first book is itself a time inversion, Recollections of Things to Come. To extend that time inversion of ends and beginnings, ends and beginnings that are leaving their traditional places, that first book was written in the aura of her near-death experience from an abortion. You say her whole body of work can be seen as a treatise on memory and time. There are stories with houses where time does not elapse or with invisible clocks or parallel historical times. In the titular story of her collection The Week of Colors, we learn that “weeks did not actually follow each other in the order her father believed.” It was possible to have three Sundays in a row or four consecutive Mondays. Equally possible was Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday—but this was coincidence, a pure coincidence. It was much more likely that from Monday we could jump abruptly to Friday and from Friday return to Tuesday. In her life, there are these strange coincidences of time: Paz, Bioy Casares, and Garro all die within twelve months of each other, and their daughter dies the day before the 100th anniversary celebrations of her father’s birth. I imagine—I’m totally reading into this, but I’m imagining—she’s dying, unable to bear the celebration. But I have no idea what her relationship with her father was. But that’s how I imagine it. You connect her strange relationship to time to many things, one of them being the Indigenous culture around her, the Náhuas women who helped raise her. We see her, in her stories, not only restructured time but also even restructured the Malinche myth at one point. So I guess I wanted to end here with any final thoughts you want to share about Elena Garro and time, thoughts that can serve as the beginning for listeners to encounter Garro after hearing you speak about her today.

JB: I remember that I forgot to answer a second part of your previous question. So can I do that now? [laughs]

DN: You can if you want me to.