Keetje Kuipers : Lonely Women Make Good Lovers

From the craft of writing sex in poetry to the virtues of failing publicly, today’s conversation with poet Keetje Kuipers is not to be missed. We explore everything from storytelling within poems to the dialectic between control and wildness; everything from queerness and wilderness to fantasy as a portal to truth on the page.

Keetje’s contribution to the bonus audio archive is unusually generous. Part reading, part teaching meditation, she draws upon many of the themes we discuss in the main interview and finds a poem by another that exemplifies that theme, whether it be an example of what an embodied poem looks like, or who is in her lineage of nature poets of the Mountain West that are also queer women, or poems that exemplify a beautiful dance between control and wildness, and she reads these poems for us and talks about them. To find out how to subscribe to the bonus audio archive and about the other potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter, head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today’s episode.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you by poet and novelist Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi's debut collection of poems, Disintegration Made Plain and Easy. Off-kilter, uncanny, and full of a tender yet surrealist energy, this illustrated book is hallucinatory and strange, like an R-rated Shel Silverstein. Equal parts Jack Handey and Heather Christle, this is a collection Brian Evenson calls "cozy and deranged," and Lemony Snicket adds, "I am laughing and frightened and not sure which way to turn." A gorgeous gut punch and possibly the weirdest poetry collection of 2025, Disintegration Made Plain and Easy, the first release of brand new indie publisher Piżama Press, is out on May 27th. Today's episode is also brought to you by Julia Elliott's Hellions, an electric story collection blending folklore, fairy tales, Southern Gothic, and horror. Says Jeff VanderMeer, “A genius at the short-story form, Julia Elliott achieves new highs with the astonishing Hellions. Beautiful, visceral, surprising stories, both wild and dangerous, with a Southern twang but universal appeal. Elliott is an Angela Carter for our times.” And Carmen Maria Machado adds, “Julia Elliott’s fiction is its own country. Every sentence drips and unsettles, every character lusts and schemes, every landscape is alien and forbidding. But there is something eerily familiar pulsing underneath the wildness—the way your waking life snakes through the logic of your dreams. I am obsessed with these lush, feral stories.” Hellions is available now from Tin House. Back in 2022, when I did the limited series Crafting with Ursula—12 episodes over 12 months with 12 different writers about 12 different aspects of Ursula K. Le Guin's writing life—I didn't know going in what I would learn or discover or be particularly captivated by. In the end, the aspect of Le Guin's writing life that was most impactful on me and memorable was the way she learned and re-evaluated herself in public. Her journey around gender and feminism, and the way she undertook it in a way that invited the reader to see how it unfolded. Her willingness to go back and change her mind, to question herself about what she had done previously, but without ever disowning it, instead leaving a sort of open-source, citational trail of breadcrumbs. I mention this because while today’s conversation with Keetje Kuipers talks in depth about many things—everything from the craft of sex writing to storytelling within poetry, to the dialectical tension between control and wildness—one of the things I was most excited to talk to Keetje about was failure and failing publicly. About why sometimes doing this very thing is an important thing to do. This is something that Keetje has thought a lot about, and we think alongside each other today about it too. Unsurprisingly, given how deeply enmeshed Keetje is in the poetry ecosystem—a writer, a teacher, an editor, the founder of a poetry award, sometimes a poetry judge—Keetje's contribution to the bonus audio archive is unusually generous and wide-ranging. In her 20-minute contribution, part reading and part teaching meditation, she draws upon many of the themes we discuss in the main interview and finds a poem by another that exemplifies that theme. Whether it's an example of what an embodied poem looks like, or who is in her lineage of nature poets of the Mountain West who are also queer women, or poems that exemplify a beautiful dance between control and wildness. She reads these poems for us and talks about them. She then ends with a poem of her own, similar to Kaveh Akbar's contribution, where he read a poem In Praise of the Laughing Worm that he really liked but didn’t fit with the collection as a whole, so it remained outside of it. Similarly, Keetje reads a poem like this that didn’t make it into the new collection, meditating on how one orders a collection, what story the book tells as a book because of the choices you make in this regard, and why this particular poem would change the story of the book in a way she didn’t want it to. This joins bonus readings from so many iconic poets—Jorie Graham, Dionne Brand, Danez Smith, Layli Long Soldier, Natalie Diaz, Forrest Gander, Arthur Sze, Ada Limón, Alice Oswald, Rosmarie Waldrop, CAConrad, Nikki Finney, and many others. Subscribing to the bonus audio is only one possible thing to choose from when you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. Every supporter can join our brainstorm of future guests, and every listener-supporter receives supplementary sources with each and every conversation. Then there's a whirlwind of other things to choose from. Yes, access to the bonus audio is one of them, but also the Tin House Early Reader subscription, getting 12 books over the course of a year, months before they’re available to the general public. Rare collectibles from past guests, a bundle of books selected and curated by me and sent to you, and more. You can find out more at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. And now, for today’s episode with Keetje Kuipers.

[Intro]

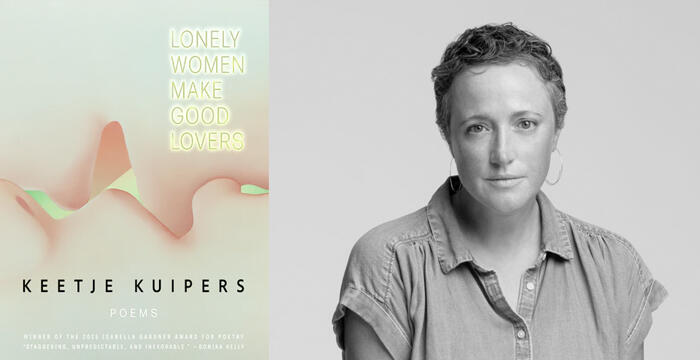

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest, poet and editor Keetje Kuipers, earned a BA at Swarthmore College, her MFA at the University of Oregon, and is the author of four books of poetry. Her debut, Beautiful in the Mouth, won the 2009 A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize from BOA Editions and was named a Top 10 debut poetry title by Poets & Writers. She followed this with The Keys to the Jail in 2014 and All Its Charms in 2019. Kuipers' writing has appeared everywhere from Poetry Magazine to The New York Times Magazine, to NPR's The Writer's Almanac, to American Poetry Review, Orion, The Believer, and more. It has also been reprinted in The Best American Poetry and in the Pushcart Prize anthology. She's been a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford, is a 2025 NEA Fellow, has been a visiting professor at the University of Miami and the University of Montana, and an associate professor at Auburn, where she was also editor of the Southern Humanities Review and where she founded the Auburn Witness Poetry Prize in honor of the poet Jake Adam York. Kuipers has been on the board of the National Book Critics Circle, has been a judge for the National Book Award in Poetry, and is on the advisory board of the Dual Language Writers Conference Under The Volcano in Tepoztlán, Mexico. She co-curates the Headwaters Reading Series for Health and Well-Being in Missoula, Montana, which focuses on using poetry to build knowledge and trust among community members around issues of health, Native health, women’s health, LGBTQ health, mental health, disability, and more. If that were not enough, since 2020, Kuipers has been the editor of Poetry Northwest. During her tenure, she founded the James Welch Prize for Indigenous Poets. Keetje Kuipers is here today to talk about her latest book, which, like all her collections, is out with BOA Editions, called Lonely Women Make Good Lovers. With starred reviews from both Foreword Reviews and Publishers Weekly, poet Marilyn Hacker says of Kuipers’ latest, “The poems are elegant, earthy, and pertinent. Kuipers moves language marvelously, and I love her understatedness, making lyrics of what could be ‘politicized’ texts, which are all the more persuasive for the transformation.” Donika Kelly adds, “Keetje Kuipers’ Lonely Women Make Good Lovers is a staggering, unpredictable, and inexorable collection. Caught in the nexus of hunger and ruin, Kuipers’ speaker explores the atmosphere between what she knows or almost knows and what cannot be explained. Recognition of the self, of others, Kuipers shows us, is a practice. A compelling read, these poems are nimble and vulnerable, mapping a return to the self, a return to longing, a return to the archive of what the body remembers.” Finally, poet and critic Stephanie Burt says, “How does romantic love bring us together—or isolate, or confound? What if there's a baby on the way? What if we come to each other naked as birds in flight, as stripped logs, as old photographs, as pure ideas? What does a grown-up, clear, thoughtful, emotionally available, gifted lesbian poet get when— decades after Adrienne Rich—she comes up, still wearing her tanks, and takes her mask off, after the proverbial wreck, and makes ‘a pact with the world,’ with her wife, with their earth and air? This poet is your poet. Here are your poems.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Keetje Kuipers.

Keetje Kuipers: Thank you, David. That was like a weird, almost out-of-body experience, having listened to so many of your introductions for other writers while I've been folding the laundry or driving to pick my son up from preschool. That was like a strange dream. [laughter] Thank you.

DN: Well, I think the first time we talked was now six years ago. So I’m glad we’re finally here.

KK: Me too.

DN: Yeah. Well, I wanted to start with situating your new book among your previous books for a couple reasons. For one, even though your new book and the one just before it, All Its Charms, are distinct—with a different feel, a different focus, and more—there’s also very much a sense of continuity, of chronology, of the furthering of a story as we are again with you within the same relationship and family, even if what is foregrounded and explored is different. It made me think of a couple of things. For one, how you’ve talked about how the MFA poetry education you received at the University of Oregon was very narrative-based, where storytelling was a big part of the program’s ethos, which I suspect is unusual for poetry departments. I can feel that within your poems, but also with regards to the connective tissue between the most recent two books. So I’d love to hear about how you see these two books in relation to each other. I guess how you would characterize them separately and also sequentially, how they relate and diverge in your mind.

KK: Yeah, I think it's hard for me to think about these two most recent books simply through the lens of craft and the arc of craft. Those are obviously really important elements to those books. I can talk about that briefly before I get to what feels to me like the larger concerns that were shaping the evolution of those two books. But I think having Dorianne Laux and Garrett Hongo as my mentors in graduate school, I was getting all kinds of an education from each of them and from my peers in that program who were phenomenal. From Dorianne, I was learning a lot about the importance of narrative and the importance of story. From Garrett, I was learning a lot about the value of metonymy. From both of them, I was learning music in different ways. Music, I think, when I look back, seems to be the place where those two mentors overlapped the most and maybe even influenced me the most. In thinking about the evolution of these two most recent books, I got very into, with my second and my third book—All Its Charms was my third book—I got very into polishing the poems to a perfect kind of shine. I think I lost some of the wildness in my first book. That first book was primarily written in graduate school and the two or three years after graduate school. I didn't have so many rules for myself then. I was just willing to not just play, but if I did something playful, to leave it at that, to appreciate it for its play. Whereas in my second book, which I wrote while I was a Stegner, I felt tremendous pressure to push myself to some kind of next level. You think you get a fellowship like that and you think, "Oh, now I just have these two years to write and simmer inside this reading and writing world." Really, the pressure was so tremendous, and it was internal pressure, not external. It was so tremendous. I wrote poems that I look back on, I can't stand them. I can't stand them partly because they were full of ache and pain, but also because they were really trying too hard to be something that I am not as a writer. So with my third book, I was still stuck on polishing and on perfection. Everybody knows that the poem that's had plastic surgery performed on it is really not so beautiful as the poem that's born into the world with its many freckles and birthmarks and imperfections. I'd rather add some tattoos and some scars to my poems than get them botoxed. So I think with that third book, with All Its Charms, I started to remember that, but I was still polishing. With this book, I think I'm back there now. I think I'm back to appreciating maybe not imperfections, but the amazing particularities of what any poem might do or be on the page and not feeling like—I mean, I revise the hell out of my poems—but not feeling like I need to revise them into submission. Yeah, so that's all the craft. But then I think there were other things that were shaping those two books that were very external to my writing process, or at least to my knowledge of how they might influence my writing process. One was that I left a tenured position as a professor in order to prioritize my queer family's happiness. That meant choosing geography over being a professor. That plunged me into a tremendous amount of doubt that I didn't see coming. So I had my second book come out in 2014, and then in 2016 was when I left that job. I had really just begun to write that third book. All of a sudden, I just completely doubted whether I belonged in the world of writing poems at all without that sort of stamp of validation. "Who am I to be writing poems?" And the poems I was writing had babies in them. "Who gives a shit about that?" [laughter] I really, really doubted the value and the worth of the work that I was making. I was lucky, beyond lucky, to find a small, intimate writing community in Seattle that convinced me otherwise. Then when that book entered the world, readers convinced me otherwise. But I didn't believe in that book. I didn't believe in it until months after it had been published. Then that changed what I was able to do with this book. I had wanted to get back to wildness, but knowing that anybody cared if I did or not was what made it possible for me to actually begin to take the risks that I wanted to take.

DN: Well, staying on the macro level of looking at your books across time, we have a question for you from past Between the Covers guest, the poet Gabrielle Bates, author of the collection Judas Goat. I also believe she first met you as your student at Auburn and is now your peer. So here's a question for you from Gabby.

Gabrielle Bates: Hi, Keetje. Hi, David. I'm holding a copy of Lonely Women Make Good Lovers to my chest right now, sort of hugging it. I love this book. I'd seen versions of many of these poems over the course of the last few years, thanks to our every-other-month-or-so workshop, and I just have to say what a thrill it's been to read the collection and see how you've managed to pull even more power and music and personal revelation forward in your revisions, and to see what's recurring across the poems more clearly now that I'm seeing them all together. I think it's so interesting that a friend of yours, upon reading the manuscript of your first book, said that you were using the words "glitter" and "glimmer" too much. And now, in your fourth book, that obsession is still with you. There's a motif I track across the book of sequins and little crystals. You describe water shimmering like sequins on a tarp, water glitterless like the back of a rhinestone, glittering fragments of shell, and the black bracelet of a scorpion. We see women gluing Swarovski crystals on foam cases, diamonds raining on Saturn. This glittering motif in the book feels like it's doing a lot of subtle but important work thematically and texturally related to questions of gender performance and convergences of natural and synthetic beauty. I'm so glad that—whether consciously or unconsciously, or a mix of both—you've allowed that obsession to recur and evolve in your work. You have a vexed relationship to certain recurrences, I know, rhetorical moves you're very good at, which frustrate you to repeat in poems, but I'm interested in the repetitions you've embraced, if any come to mind. Repetitions in the poems themselves or even in your process, which have felt generative or meaningful for you. You could reflect on the recurrence of glitter if you want, or about something else entirely, something that's maybe happening behind the poems we see, a revision strategy you repeat, a certain number of syllables per line, anything at all about repetition that compels or intrigues you?

KK: Well, first I have to say that I’m crying, which before we started recording, David, I told you I have a bit of an emotional hangover from AWP, which always just sucks every ounce of feeling out of me and then leaves me sitting in a pool of it. So I’m feeling all of that. But Gabby, whenever I think I’m going to cry, I try to picture a clown, like one of those classic sort of horrifying clowns. So that’s what I’m going to do while I talk about Gabby. I’m going to picture somebody wearing a red nose and a bright neon-colored wig. Gabby was one of my first students at Auburn University, and she was one of my daughter’s first babysitters. So when I went back to work after being on maternity leave when my daughter was born, Gabby would babysit Nela in my office while I taught the graduate workshop at night. And Nela would cry, and I’d race out to nurse her on the break, and it felt like it was fairly traumatizing for all three of us. But you’re right, Gabby started out as my student and has become my peer and has become someone who I admire and look up to so much as a writer. She’s one of those people in Seattle who taught me to believe in my work again, which is such a gift. She’s right, Gibson Fay-LeBlanc, who is an old poet friend of mine, when he first read the manuscript of my first book before it was published, he said, "We’re putting you on a glitter-glimmer watch." [laughter] And I did trim those words back in the first book. I didn’t really see them show up again so much in the second or third, but I did notice as I was reading from the book at various events this last week at AWP that, yeah, glitter and glimmer are back. And I think it’s interesting that in this book, that makes me feel like I’ve returned to a kind of wildness and freedom and risk and danger and play in my writing, that those words show up again. For some reason, they must be the place that I go when I feel activated in a certain way as a writer. Gabby is absolutely right. She knows that I hate it when I write what I call a “Keetje poem.” I really hate those Keetje poems. They come really easily. They are about 14 lines and about 10 syllables per line. Their rhetorical moves, they do move like a sonnet. They present an idea, they deepen that idea, they complicate that idea, then they question that idea, and then they throw a sucker punch at the end. [laughs] And you know, sometimes they end up being the poems that people consider, you know, like some of my best poems. Or the poems that readers get most excited about, or that people comment on after a reading. But when I first write one of those again, I am totally irritated and frustrated with myself. It feels like I'm just using my strongest muscle, and I want to use all the muscles. I want to work those weak ones, and it feels like cheating. I've tried to get myself not to feel that way about it. I've tried to get myself to embrace my strengths and to realize that I'm writing those "Keetje" poems because they are something that, after years of working hard, I can come to in a more sort of easy and unconscious kind of way. But like I said, there's something about it that feels too easy, and that makes me less interested in writing them. To me, they feel predictable, even if to a reader they might feel full of surprise. Other repetitions, I think we never know until somebody else tells us what we're doing a lot of. My first book had a ton of boats in it, which I didn't realize until a reviewer noticed it. My second book was full of my dog, which I didn't realize until someone pointed it out. I'm not sure yet, other than the reoccurrence of glitter and glimmer, what it is in this book that's repeating itself or showing up again. But Gabby's right that I do—as much as I don't want to write "Keetje poems"—I do have, I wouldn't say moves that I fall back on, but I do have some sort of formal constraints or craft choices that help me when I'm revising. Those 10 syllables per line feel like a life raft to cling onto in the revision process. A lot of times then I break out of that in a final draft of a poem, but that is something that helps me when I want to tighten a piece and I want to make sure that there's absolutely nothing in there that doesn't belong. I'm pretty obsessed with making sure that every word in any given poem points towards what is at the poem's heart. I want to make sure that every adjective is not serving just that particular moment in the poem, but the poem as a whole—every noun, every verb—that each of them is pointing. That doesn't mean creating a poem where there's one umbrella metaphor. "Oh, this one is the ocean." I want my poems to be full of strangenesses, like that Jack Gilbert poem where suddenly raccoons are licking the inside of a garbage can. I want those strangenesses, but I want all of them to be pushing towards the same thing. That’s something that I hold onto anytime I’m crafting a poem.

DN: In that spirit, I also think of something you said that Gabby six years ago in The Adroit Journal, which isn’t about repetition but rather a breaking, I think of the illusory boundary between books. That the last poems you find a place for in a given book feel like the impulse for what's going to come next. It reminded me of a similar sentiment that Jorie Graham expressed the first time she was on the show, that within each book of hers, there's a particular poem where something happens which is new, which is at the border of that book, which is the next thing she needs to explore. It always has to do with a formal or musical discovery. You yourself have talked about how your second book, The Keys to the Jail, was written from a place of self-blame. And yet there were two poems at the end which granted a begrudging forgiveness to yourself, a forgiveness that then expands in your next book, All Its Charms, into something that is not begrudging but more full of wonder that forgiveness is even possible, and that there might be joy on the other side of it, to paraphrase your words. But back six years ago, you said the last poem added to All Its Charms—called “Digging Out the Splinter”—was the poem that you saw back then as suggesting the new energy of what would come next. I wonder if that still holds true. If so, if you could dig out the splinter for us, carrying it forward into this collection. But also either way, if you could also talk about how shifts in focus and theme manifest in shifts in form between your last book and this one. Three years ago, you said in a CutBank interview that this new book feels more like your first book—something that you've already mentioned today—much more like your first book than any of the others. Whereas since then, you've described your work as making sure that the poems fit imagistically and lyrically what you call a kind of poetry sudoku. But now you're returning to a more formal wildness where you're allowing yourself to let words feel wrong or images remain that don't quite belong to the world of the poem, so maybe even contradicting what you just said about everything pointing in the same direction. Again, this is years ago now—both of these interviews—but talk to us about whether there is a seed poem from All Its Charms that's now blossoming in Lonely Women, if it's still the same poem.

KK: Yeah, I think that poem “Digging at the Splinter” was one of my earliest attempts at a very honest poem about being married and how complicated it is. And how ultimately—I mean, people talk about marriage as a compromise or a series of compromises. And I don't really agree with that, at least not the way like in pop culture we think about a series of compromises. Like, "Oh, one compromise is that my spouse snores or is terrible at loading the dishwasher, or doesn't like going to see live music with me," or whatever it might be. But I think it's a series of compromises in terms of letting go of the self that we cling to so desperately. This single identity that, for better or for worse, it's terrifying to let go of. I have found myself many times over the years wanting desperately to hang on to my anger, to hang on to the usefulness of blame, the usefulness of regret. And the great compromises of marriage are that I don't get to do that anymore. You know, anger, blame, regret do not get to be safe places for me to hide. So I think that poem about the splinter is maybe the first poem that started to really think about that honestly. It made space for my ability to do that work, that really uncomfortable and painful work, of giving up the bad crutches that the self wants to make use of all the time. Examining that in more poems. That's what I feel like I got to do as part of the project of Lonely Women Make Good Lovers. Maybe figure out how did I come to be using those particular crutches to hold myself up as a person, and especially a person in relation to my partner, my friends, my family. What would it feel like to fling those off of myself?

DN: Yeah. Well, could we hear “Digging Out the Splinter” from your last collection, and then the opening poem of your new collection?

[Keetje Kuipers reads the poem called Digging Out the Splinter]

[Keetje Kuipers reads from Lonely Women Make Good Lovers]

DN: We've been listening to Keetje Kuipers read both from her last collection, All Its Charms, and her latest collection, Lonely Women Make Good Lovers. This feels like such a bravado opening to me. To open a book with you and your ideal fantasy lover looking lovingly at your sleeping wife from her bedside before you and Garbo succumb to your desire for each other, and that the people presumably awake in this poem are clearly in a dreamed scenario, and the sleeping and possibly dreaming wife is in the very real world of the poem in a way. It's such a wonderful inversion. I think this opening also points to an important quality about your work, which is an attraction to taboo, not just voicing this fantasy, but imagining it with your wife unconscious next to you while having it, and having this be the poem we first encounter in the collection. But in your last book, too—a book centered less on Eros than on motherhood, but motherhood in a far from sentimental way, not editing out the baby shit in the bathwater, for instance, not afraid to write a poem about your white daughter with her Black doll. But talk to us about the gesture of the Garbo poem, which seems to say something like, “Look out, this collection might go anywhere.” And talk to us about what it means to hold open the space for what is often thought, but so often kept to oneself, that it's usually left unsaid, let alone fully dramatized like you have, creating this space, inhabiting, embodying. There's a narrative here again. So you're really holding a space for this unspokenness in this poem.

KK: Something I had really never played with in any of my poems before I wrote this one was using magical realism in my work. And what I kept finding myself coming up against in my last book, All Its Charms, that really frustrated me was the inability to make sense of the complicated narrative of my life in these narrative poems that I was writing. I had always dated men my entire life until I met my wife. Then we were together for three years. Then we broke up for seven years. I dated exclusively men again. Then she came back into my life at a time when I had already made the decision to become a single mother by choice. I said, "You can come along for this ride of me being pregnant if you want to, but I'm doing this thing." So we did. We got back together, but we did everything out of order. We were long-distance while I was getting pregnant and had a baby and was raising a baby. And then we got married. And then we still didn’t live together for another six months after we were married. Then she adopted my daughter years after that. It’s all out of order and a little confusing and doesn’t fit so easily into what many people want to think of as the story of like, “Oh, when did you come out?” and “Oh, when did you and your wife decide to have children?” I’ve not been a very static being. So trying to write poems that include transformation, a chronology that doesn’t match up with what we’re sort of culturally attuned to, with dwelling in gray areas, that was super frustrating for me in All Its Charms. What I decided with Lonely Women Make Good Lovers is that I needed to find a way in my poems not to make excuses for those complications or even what some might consider inconsistencies, but instead to find a way to embrace them and to dig into them in the poems. So that was sort of how I stumbled into making use of magical realism. There are a few other poems in the book that do that as well. Once I started doing that, and once I started going back and reading Alberto Ríos and thinking about it, I realized that there’s really nothing better suited to the queer experience and trying to make it legible on the page than magic. So, for me, in this Greta Garbo poem, there is the magic of fantasy and of the strangeness of combining desire and the erotic with having my kid appear in the poem. And yes, those layers of dreams and dreamers and my wife—I mean, my wife jokes I talk about how this book is about her and she’s like, “Yeah, well, I’m asleep in most of the poems that I appear in,” so she’s doubtful. [laughter] But really, the magic is in pursuit of a fuller queerness on the page in many ways.

DN: Well, staying with your wife as a character, given that there is so much narrative, and this is usually something I’ll ask people who are writing memoir, but it completely applies to you, we learn a lot about your marriage and your family, down to your sex lives. But before we talk about sex, I did want to ask you how you navigated this, if at all, with your wife. How the two of you negotiated—if there is even a negotiation—what parameters you have or don’t have of what will or won’t find itself in a poem about another person whose relationship matters to you. Obviously, not any person, but a person where it would matter to you if it caused a rupture, if you did it wrong.

KK: Yeah. I’m thinking—this hasn’t really occurred to me before—but hearing you describe her as a character, which of course is what she is in many of these poems, it makes me realize that I think part of the reason she’s asleep in so many of them is because when she’s awake, she’s an absolute saint. When she’s really the best person in the entire world. So that’s not very interesting, having a saintly, perfect person in a poem doesn’t make for a lot to dissect and to dig into. But I’m the villain in the poems. And I think that’s true to how I see myself in the marriage as well. So I’m the villain who writes about it as well. Like, that’s another “bad” thing that I do. My wife would object to all of the things that I just said. She would say that I’m not the bad guy and that there is no bad guy in our marriage and that I’m too hard on myself. And I think that that level of compassion and forgiveness from her is what allows me to write the poems. If I thought that she thought that I was the bad guy, I don’t think I could write these poems. So that amount of compassion and forgiveness from her allows me to write what I’m most afraid of, which is—as you said—any kind of rupture that could occur in our partnership. But she’s not a writer. She’s a lawyer. She calls herself a simple person. I would call her matter-of-fact. She is incredibly proud of me. But I don’t share my work with her as I’m writing it. I don’t really even share it with her as I’m publishing it. I will sometimes talk about poems—we talk about our work lives—and I’ll be like, “Yeah, I wrote this wild poem,” or “I managed to squeeze our vacation in Palm Springs into a poem,” or something like that. But when this book arrived in the mail as an arc, I had a moment of panic because I realized she hadn’t read all these poems, and that she needed to read them before anybody else did. That is really her one thing. She just wants to make sure she's the first one who knows. That to her is the sort of measure of intimacy. She did read it, and she said it was great and that she was proud of me. But I sort of pressed her, like, "Are you okay with this? Are you okay with these? Like, do you want to talk about any of these poems?" And she said something which I think is really smart, and which is the way I'd never thought about it. You know, no matter how much I reveal in a poem, there's so much that I can't fit in. And all of that is ours. So she understands very wisely that these poems are a slice of our love and our marriage and our struggles that are then sort of distilled or sharpened or honed in some way. But there's all the other stuff floating around them in a cloud and little puffs and wisps of smoke and fog, and that maybe that more sort of ephemeral stuff that I don't pin down in the poems is what our marriage is really made of, and that only belongs to us.

DN: Well, before we talk about sex and writing sex, let's hear a couple more poems before we do. I was hoping for Magician at the Woodpile and Bleeding.

[Keetje Kuipers reads from Lonely Women Make Good Lovers]

DN: We’ve been listening to Keetje Kuipers read from Lonely Women Make Good Lovers. So recently in The Cincinnati Review, you wrote an essay called “Breakwater”: On the Craft of Sex in Poetry. It's an associative modular essay that has lots of memorable insights such as, "In order to believe that I can be desired in a poem, I must desire myself first. I can’t write the poem where I have sex unless I believe in the sex, the same way I can’t press the vibrator to my own body with any hope of pleasure without believing my body deserves that pleasure." You also talk about how you bring your purple vibrator to writing residencies because it reminds you, like your daily walks, to be in your body while you're there. You say, "To successfully make the transition to the page without the poem losing its inherent embodiment—its lived music—requires a commitment to imperfection and surprise, to being overtaken, to losing, at some point, the control that many writers hold dear." You’ve also offered a generative workshop called “O let me, please”: How (& Why) to Write the Sexiest Poems of Your Life, where you quote Melissa Febos as saying, “When something seems difficult, in writing and in life, we tend to make rules around it.” You continue by saying, "Just as there are a myriad of cultural norms around sex, there are a million rules about how to write it, too. But rules were made to be broken by poets—or re-invented on our own terms" Talk to us about embodied writing and about what a commitment to imperfection means in regards to this, about writing sex, and what poetry or sex writing rules, about which poetry or sex writing rules are broken in doing so?

KK: I'm thinking again about what we were talking about earlier, about letting poems have parts in them that maybe seem like they don't match up or they don't belong. That Magician at the Woodpile poem, for instance—I mean, I think of that as a love poem. That is a love poem to every one of those dicks. You know, the poem is full of a kind of voiced gratitude for each one of them and our time together. I think there are a number of poems in the book that try to do that, that try to talk about a sort of gratitude. We're told all the time to live in the present. I think that's great, be present. Be present in your life. Don't be on your phone. Be here in the world. But I think also like it's wonderful to be present in the past and to allow oneself to feel fondness, not just gratitude, but fondness and love for all the people we've ever been. So it's a love poem to those dicks. It's a love poem to who I was with those dicks. It seems to me that if I'd written that poem earlier in my life, it might have instead been an angry poem or a poem of rejection. "I reject that straight self who existed before. I disown her. I disown her desires that she once had and acted on." I don't want to write poems that disown any part of myself. I don't think they're very interesting to write or to read. I think it's much more compelling to enter into a poem knowing that the agreement is not to make a point, though I do believe deeply in rhetoric in poetry and the importance of argumentation in poetry, but is to complicate the point. That's what I'm wanting to do. And I think the body is a great way to complicate the point, because famously, the body does not lie, and what the body wants or what the body doesn't want sometimes doesn't seem to make sense. I had an experience at AWP this last week. I was riding in a Lyft, and it was like a horrible Lyft ride for me. If anybody else had been in that car with me, they wouldn't have thought that it was a terrible Lyft ride. But for me, it was a terrible Lyft ride because I was filled with desire for my Lyft driver, who was like the epitome of some kind of straight white male fantasy, like sort of curly, dirty blonde hair, and he was probably like 25 years old and he was dressed like a day trader. He had like a button-down, blue and white striped shirt on. I mean, it was grotesque to me. My desire was horrifying to me, not because I'm ashamed to desire somebody outside my marriage—I think fantasy is wonderfully useful in so many ways in our lives—but because I was repulsed by the straightness of my desire and the obvious predictability of it and not feeling queer enough in the moment of my desire. So that's what's interesting, that's what's complicating, and that's where my body is absolutely not going to let me lie. So I think with this whole book, with each poem, I wanted to write it as far as I possibly could into what felt uncomfortable and scary to me. That meant letting my body lead the way sometimes when my mind really didn't want to.

DN: Well, I look forward to the Lyft poem, too.

KK: [Laughs] I'm sure it'll happen.

DN: You have a recent essay you published called "When Touch Becomes Political" about moving to the Deep South with your wife and how your fear of being seen out in the world at large as a lesbian couple created a feedback loop that affected the two of you at home. That the anticipated homophobia, which never did materialize the way you feared it might, affected how intimate or affectionate you were in your own house, even with the blinds drawn. You say, "At some point, it stopped being an act when we walked through our door and refused even the brush of a hand. The internalized shame had won out not only over my love for my wife and my attraction to her, but also over my most innate instincts for physical affection and touch. Gone was the intimacy we’d once so easily found together when it had just been two girls in one twin-size dorm bed." I wonder about this question of queer visibility in relation to being visible in your poetry. How the questions of this essay manifest—or don't manifest—in Lonely Women Make Good Lovers. Because I would imagine surely, that internalized shame coming into your relationship must mean that it finds itself in your heart and also in the hand that holds the pen or types the word, that this is a poetry issue. I mean, it’s obviously a relationship issue primarily, but I can't imagine how it couldn't also then become something you have to face in some way—or not—when you're writing poems.

KK: Yeah, I think one of the things that has surprised me and I think also surprised my wife is what a boon it is for our private relationship when we are public with our relationship together. There is nothing that makes me more inclined to take my wife home and take her to bed than being out with a group of friends who we feel really comfortable being affectionate with each other in front of. There's a wonderful thing, and I think this is true regardless of sexuality, whether you're gay or straight or whatever—if you get to perform your relationship in front of an appreciative audience, that's a real turn on. It's healthy inside the bedroom and outside of the bedroom. And there have been periods of time when we haven't gotten to do that as much, and then there are periods of time when we get to do it more. I think similarly, I have found myself, when I'm reading from the poems in this book, like I just did at AWP, I come away from that experience really wanting to see my wife and be with my wife, because they remind me not only of my desire for her, but just the depth of our intimacy and our closeness, and also they remind me of everything that's not in the poem that's ours. So I think in some ways what happens after the poem is written in my relationship to the poem is what affects or has an effect upon my marriage. I do not think about it at all when I'm writing the poems. I probably should. I would maybe be a better spouse if I did, but I do not think about her feelings or the poem's effect on our marriage at all during its composition or revision or magazine publication. But I think that writing the poems—I mean, speaking of feedback loops—the last few years I have tried to work on my marriage more than ever before. I think then when I'm doing that work in our marriage, in the real world, I want to do some kind of comparable work in the poems, and I'm pushed towards that unconsciously. Then once I do, I kind of want to step out of the poems and explore what I've discovered in them on the page with my wife outside of that arena. Then, yeah, that is its own much more healthful feedback loop that I think happens in the work.

DN: I love that. So back six years ago when we first started thinking about the possibility of having a conversation for the show, back then you were doing a series at Poetry Northwest called Line Cook, where you paired a literary podcast episode with a recipe. Twice Between the Covers was part of it. One was called Yuri Herrera with Zucchini Ricotta Gnocchi and No-Cook Tomato Sauce. The second is called Matthew Zapruder with Curried Chicken Thighs and Cauliflower, Apricots, & Olives. In this one you were at a writing residency—one that I particularly love—in the remote high desert of Oregon called Playa, without a good internet connection and with chicken thighs that you hadn't yet eaten and it was already your second week there. So on the one hand, you were puzzling out salmonella risk, and on the other, you were looking through what podcast episodes you had long ago downloaded since you couldn't download new ones. Episodes you called "leftover fairy tales." One of them was one lonely episode of this show, of which you said, "I say lonely because even though I adore David Naimon’s astute conversations with poets and prose writers, this particular episode was one I’d been trying to avoid listening to. Because, really, who wants to hear anyone, even a couple of beloved writers, ask the question, “‘Why poetry?’” And I should say, Why Poetry is the name of the book Zapruder was on the show discussing. So either you were going to eat cold cereal and listen to a retelling of Rapunzel, which was a previously downloaded episode of a podcast for a car ride with your daughter, or you were going to cook questionable chicken while listening to Zapruder, a poet you admired, make the questionable and, for you, unnecessary effort to get you to enjoy reading poetry. You say, "You know how sometimes it’s really nice to be proven wrong? Zapruder and Naimon got right down to business, and were soon talking about psychotherapy and the fictive spell and how Wallace Stevens was a crackpot philosopher. ‘What a couple of lovable nerds!’ I thought, as I chopped apricots and mixed spices. ‘This is outstanding!’ You could actually hear the moments when the two of them sort of took a breath to wonder in amazement, like they were both gazing up at the stars or at least a really pretty satellite crossing the sky. The bottom line is that I didn’t get food poisoning and I think I might actually give Zapruder’s new book a read. Sometimes scarcity is a good thing." I bring this up because this is a rare and wonderful thing for me to learn that a poet or listener or art-maker is interweaving and pairing meditations on food and cooking with one of these conversations. Or an anthropologist who's teaching a class using Crafting with Ursula, the series, as its structure. But you've now outdone yourself, Keetje Kuipers, as you have a poem in this book about masturbation, which you describe in your sex-writing essay as follows: "Writing it is an act of daring myself to be seen—or fully heard or felt—not by others, but by myself." Yet, even though this is daring yourself to be seen by yourself, not by others, this poem of self-pleasure and of self-seeing called Greek Chorus was influenced by outside forces—by others—namely by my conversation with Alice Oswald, where in the endnotes you say, "This conversation inspired the rhetorical framework that allowed this poem to find its voices." So thinking of food and thinking of masturbation, I was hoping you could introduce us to how Alice finds her way into shaping Greek Chorus, which is formally different than most of the book. Then hopefully we could hear Greek Chorus together with Eating Sea Urchin.

KK: I'm thinking still about embodiment and pleasure and enough food. And one of the greatest pleasures that I get on sort of a daily or weekly basis is feeding my family, which sounds like a silly little thing, but when they moan while they're eating, like nothing could feel better to me. My wife and I joke about how I've taught our children to make moaning sounds when they eat because I do. They learned it as little people and now it's something they do too. I mean, they have extremely high standards so I don't get a moan all the time, [laughter] but yeah, I love thinking about what poetry and food have in conversation in the body. The way when you're at a poetry reading and somebody reads and it's really good, there's a "mmm" sound, you know, that the audience makes or a sighing sound. It's the same thing when we consume a really delicious meal of chicken thighs and apricots and cauliflower that haven't gone bad yet. When I'm on residencies, yes, as you mentioned earlier, I like to bring my vibrator because it keeps me in touch with my body, and never do I have so much time to enjoy myself as when I'm on a residency. But I also really like to spend a lot of time listening to podcasts when I'm on residencies. I'm writing and I'm reading a ton—reading an absolute ton—but I like to either, when I'm taking a walk or when I'm cooking a meal in a residency, or as I did when I was at Storyknife, which is a residency in Alaska where you don't have to cook any of your own meals, I did an embroidery project and I would just sit there and listen for hours. I remember distinctly embroidering some bunnies while listening to you, David, have a conversation with Charif Shanahan. So I was listening to this interview with Alice Oswald when I was on residency at the T. S. Eliot House in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in the little room on the ground floor that used to be the cold room where they would, I think, keep the milk and butter and things when it was T. S. Eliot's family's summer home when he was a child. I listened to your podcast because they're delightful and also because they make me feel so much smarter after I've listened to them. And this was one with Alice Oswald where I got to think about the role of the chorus, the role of the Greek chorus, and the role of the character, and the role of the accumulation of characters in our lives, and the choruses that we get to play back in our own minds—the best choruses. So yeah, I'm glad that that conversation brought me to this poem.

[Keetje Kuipers reads from Lonely Women Make Good Lovers]

DN: We’ve been listening to Keetje Kuipers read from Lonely Women Make Good Lovers. So I want to spend a good amount of time with my favorite element of your way of being a poet in the world and writing poetry in it, which is your philosophy of failure. You curated a series of meditations on failure at Poetry Northwest, where each week a different writer presented a piece of theirs they considered a failure. Your introductory text to the series as a whole is really amazing. It's called "There's no way you'll ever be able to get this right." And in it, you recount the time you were working on the poem in your last book about your white daughter's Black baby doll and also listening to a lecture at Bread Loaf by Terrance Hayes on practicing failure, how you had been too scared to share drafts of this poem with your POC poet friends, while at the same time every white poet who saw it said you shouldn't try to publish it. The feedback you received was that the combined elements of race, ownership, and the body created something too sensitive and complex for you as a white poet to touch. In other words, there was just no way you'd get it right. You had, in fact, drafted and redrafted it until it became "neutered of all emotion and all risk." But in listening to Terrance, you had the revelation that the poem's meaning, its very reason for existing, was intricately bound up in its inevitable failure, that the purpose of writing it wasn't to get it right or absolve yourself or demonstrate your allyship, that the initial impulse wasn't to look good, that you started writing it because it scared the hell out of you. I want to quote more from this essay of yours because there's so much in it. But before I do, talk to us about poems whose reason for existing is connected to their inevitable failure.

KK: Yeah. Yeah. Well, I'm a failed person. Like as much as I want to be deeply compassionate, unselfish, generous beyond measure, like I fail at all of those things constantly. So to write poems where I would try to represent myself as not failing at those things, they're not only lies, but they're uninteresting. There are certain kinds of failures that anyone would be interested in writing into in a poem. There are failures that we don't mind so much, or that we've come to terms with, or that are publicly acceptable, and privately acceptable as well. Then there are failures that, yeah, that feel untouchable, culturally, personally. And so I think that is what I was coming up against in trying to write this poem, was this untouchable kind of failure. I got really interested in this book in humility, and I've taught a class on humility and poetry. One of the assignments that I love to give to the students is I ask them to think of the time when they were really embarrassed or ashamed of themselves. And I say, you know, not like you fell off the stage at your fifth-grade talent show and everybody laughed at you, but where you said something or did something that deeply wounded another person. Maybe you didn't even mean to, but you did. We all have those. We all carry them around inside of us. I think there are a couple of poems in this book. There's a poem in this book called I Wasn't Trying to Steal Her Boyfriend. And before this book came out, I reached out to the person who is the "her" in the poem. I said I wrote this poem and I sort of apologized for like re-inscribing that wound. She said, "Keetje, I don't even remember that. You're wonderful. I love you. It's fine." And so those things that we do where we wound somebody else are the wounds that actually we carry around painfully inside of ourselves, often much longer than anyone else who we hurt. So I want to encourage my students to write those kinds of poems. I want to encourage myself to read those kinds of poems. There are a number of those poems in this book. One of the panels that I was on at this last AWP was a sex poems panel. Some of the questions from the audience at the end got me thinking about writing poetry from the place of having been the perpetrator of sexual discomfort in another person. Like, that's a poem that I've not written. That's a poem that I've not really read. I think like, okay, that's the next dangerous, scary place for me to confront, maybe in my work, or one of them anyway. And again, it's not about making myself look good, not about absolving myself, also not about glorifying. I mean, I think there are lots of poems out there that I get very frustrated with that I see come across my desk at Poetry Northwest, for instance, in the submissions, where someone is thinking they're writing the poem of amends, and really they're writing the poem of the glorification of their own chaos and harm that they've done to others. I really don't have any interest in those poems at all because there is no amends. Certainly, nothing can be made in a poem, that's not how that works. So, I think instead acknowledging and living with and dwelling in the poem, in the failure of myself as a person to be the person that I so desperately want to be, that I want to imagine that I am, is the only way to get into those poems and to, again, write the poem that's complicated enough to be worth reading.

DN: Well, to stay with that essay a little longer, one element of this, it seems to me that seems particularly important is not that the poem is a failure, but that certain failures, certain ones that can't do anything but fail, with these types of failures, it seems like you're arguing that there's something useful and important about sharing them, about being public alongside them. For instance, you talk in this essay about how this poem about the black doll, which you do end up publishing, was the first poem that you had ever submitted for publication where you knew it would never be finished and could never be finished and that it remains a failure. You say, "Like many of us, I wish to commit no harm through my work. However, at the same time, I feel deeply that we can do no good without risking harm. Mostly, though, I think we risk embarrassing ourselves. And we should." You go on to talk about, among other things, the Tony Hoagland debacle about the poem he wrote that when he visited Claudia Rankine's class, the students confronted him around its racism, and he responded that the poem was meant for white readers. This prompts—this isn't in your essay, but this does prompt a public exchange between Hoagland and Rankine, something that I discussed with Claudia on the show 10 years ago, and if I remember correctly, possibly also in one of my conversations with Lacy Johnson, who I think was one of the students when this happened. But either way, your takeaway is not that he shouldn't have published this poem. Rather, the problem was, in your mind, that he didn't own up to it being a failure, a full-on mess of an attempt by a white poet to engage with race. Similarly, you say of the controversy around Dana Schutz's Emmett Till painting, which you say, "Would be way more interesting to engage with if she admitted and understood its deeply elemental failure, her failure, and could talk about it openly," I really love this, and I think it's needed to somehow de-stigmatize taking these risks, perhaps by taking the risks and taking the heat. Because I remember when Claudia was on the show 10 years ago, she was talking about how white writers need to practice staying in their own bodies as people raced as white within their work, not as unraced universal ciphers. But in the world at large, it feels to me that this is entirely disincentivized to do. If you try and you fail or only partially succeed, you simply invite yourself to be piled on about it and you likely will be piled on about it. So I wonder if starting from this place that it's important that I fail like this publicly, is part of the solution. But I want to hear more thoughts about this phenomenon of recognizing from the beginning, not necessarily the impossibility, but say the improbability that you waiting into this topic from your subject position could fully work.

KK: Yeah, I think the thing that strikes me in the idea of getting comfortable with failing and being willing to fail publicly as a white writer engaging with race in America, engaging with the incredible privilege of my white body moving through this world and this dangerous country and the incredible costs that the bodies of color around me pay in blood and with their lives simply for living, I think the thing that strikes me is that to say, "Okay, I'm okay, I'm going to go there and I'm okay with failing," is actually just like a little part of the step. Because then what happens when you fail and you get taken to task is you have to remain permeable. You have to remain open. You can't say, "I signed up for this. I'm going to tough it out. You know, I'm going to take it. I'm going to take the hits." That is not you taking the hits. You taking the hits is letting it fucking hurt. Let it hurt your pride. Let it hurt your ego. Let it hurt all those small insignificant things that for any individual are the most painful things and the most meaningless in the grand scheme. That is what we're most afraid of, the self, the precious fucking self, and it's the thing that matters the absolute least. So we have to put the most painful, least important thing on the line in order to be a part of the world that we're writing about. That, to me, feels like the barrier that we don't quite articulate when we're talking about what I think of too as a necessary kind of writing and a necessary task that we should all be taking up.

DN: Well, before we talk about how you take risks and fail within this new collection specifically, I did want to mention that you've given a craft talk at Sarah Lawrence called "Beyond the Precious Self: Publishing Your Failed Poem" and you've also said that as editor at Poetry Northwest you accept poems that are not perfect, poems that "might have a scar or a limp or a bruise but that also have a pulse." But obviously, not all failures are good or interesting or useful. So I've been asking myself how you judge when a failure is something worth trying to publish or useful to publish. Perhaps you can remember this wondering of mine as I play a question from someone else, because in the spirit of my question, we have a question for you from the poet, Annelyse Gelman. Gelman is most recently the author of the book-length poem, Vexations, which was longlisted for the National Book Award, the winner of the James Laughlin Award, where Solmaz Sharif and Aracelis Girmay say in their judges' citation that, "The world Gelman creates is a strange, slant rendering of our own, delivering shock after shock of recognition in our reading of its intimacies—clarity, threat, pleasure, dread." She's also the founder of Midst, which is a publishing platform that captures and saves and shares the writing process, where each poem includes an interactive timeline showing how each poem has been written, edited, and revised. In a minute, we're going to spend a little time with the poem from your new collection that was in Midst in its various iterations. But first, let's hear a question from Annelyse, which is not about this poem in particular. So here's the question from Annelyse.

Annelyse Gelman: Hi, Keetje, it's Annelyse. I wanted to quote from your process note for the poem that you wrote from Midst. I think there's so much in it to ask about. You wrote, "A poem is an opportunity to investigate something complex. I begin with the knot of that thing. Rather than trying to untangle it, I simply want to be able to see the threads more clearly—to understand how something becomes tied so tight in our minds. So while it might seem that I'm wrestling with language when I revise, the choices provided for me by language, for instance, syllabics, line breaks, figuration, are really just opportunities to wrestle with the rhetoric. What I am trying to do is get the knot to open up a bit so that I can lay its complicated and still tangled form out on the page." Then you say, "This becomes an even more delicate and dangerous undertaking when the poet is implicated in the knot, which is the only kind of poem I'm interested in." When I watch your writing process unfold, I can clearly see how you implicate yourself in your poetry. I see you constantly returning to what you've just written to ask yourself and the poem, "Is this true? And could it be more true?" I'm curious about how this relates to the way that you read. How do you know when a poem implicates its poet? What do you think makes that implication feel sincere? And can you speak more to the idea of implication and why it's so important?

KK: I love that she found that question, "Could it be more true?" in watching the way that I wrote that particular poem. And I think that is, that is how I push myself in a lot of my poems, especially the ends of my poems. I want to know, not only is it true, but could it be more true? And I think that's what I'm looking for too, like when I'm reading submissions for Poetry Northwest, you asked how do I know when it's a failure worth publishing? [laughs] And obviously, I don't want to publish poems that are failures because they're lazy or insufficiently examined. I want to publish poems that are failures because they tried very, very hard to reach towards something and maybe fell a little bit short. So if I'm asking of others' poems, "Could this be more true?" Maybe what I'm really asking of those poems that I read that come across my desk is, "Is this not more true because the poet decided to remain hidden and remain afraid? Or is it not more true because it's been pushed to the absolute edge of what any writer is capable of in telling the ‘truth’ of themselves in the world?" So I'm looking for risk all the time, and danger even. But yeah, I'm looking for a kind of, here's some bravery, of misstep and the kind of misstep that might take somebody right off the edge of a cliff. That's what I'm looking for in those poems and in my own. As for complicity, I think that goes back to what I was talking about before with notions of humility. I mean, if we are really trying to practice being in relation with each other, both in the world and on the page, then that first humble move is one of acknowledging our involvement and pivotal involvement in harm. So that has to be not where we work towards, but where we start from in taking on these poems.

DN: Well, before we talk about your poem in Midst, which is also in Lonely Women Make Good Lovers, could we first hear it—Boat Puller / Bird Woman / Madame Charbonneau?

[Keetje Kuipers reads from Lonely Women Make Good Lovers]

DN: We’ve been listening to Keetje Kuipers read from Lonely Women Make Good Lovers. So, not that I'm the right person to judge, but to me this is a much more successful failure—that is, if you consider it a failure at all—than the ones in the last book, I think. The previous ones feel like your refusal to ignore the way you are raced and even the ways you're inadequate to bring it into your poetry. But within your poetry, not just with the black doll, but with white passivity around the ongoing killing of Black people and self-care at the playground, and another poem that is in response to the Muslim ban and engages with Japanese internment. But in a way, it feels like, I don't know, I feel like the poems in that collection, I like them, and yet I feel like you've inserted this piece into them that, in its imperfection, is pointing at something. But here it feels like these larger structural violences live more fully or complexly to me, or that they find a way to really root down and breathe within the poem. The reason I presume you might put it in the same category as the other so-called failed poems you’ve published is only because you say in the end notes that it was a privilege to publicly work through the blind spots and missteps through Midst’s interactive time-lapse software. I’ll point people to this so they can see what Annelyse is doing over there. But when you say “work through the blind spots and missteps,” you follow it with the parenthetical “many remain, I’m sure.” So talk to us about working your way through blind spots and missteps with this poem—what the blind spots were, how Midst helped you find your way through, and if there were other ways you found your way through, did you gather readers like you did for the black doll poem? Did you seek out Native readers? And either way, talk to us more generally about the original impulse that brought you to the page to write this and how you did, especially given all the documentary sources that are quoted within it, that I was really impressed with how you read it right now, by the way, changing your voice with the various sources.

KK: I don't think I've ever read this poem for an audience before, so that was a new experiment for me. I'll start by saying that I did not bring this poem to any of my Indigenous colleagues to read and give me feedback on. I think for a couple of reasons, I mean one, I think they have enough work to do, they don't need to do that work for me. And two, if I were to do that, what would I really be asking for, right? I would be asking for—I would want to get the okay, I would want to get the green light. And that's a shitty thing to ask for. [laughs] And also, not what we're after here in this work. So I would be asking to be told that I was okay and that I did it okay, and that can't be what writing a poem like that is about in any way. I keep going back to what Annelyse said about, is this true and could it be more true? When I was drafting this poem in Midst—I mean, when I’m working on a poem in a Word doc, I’ll put filler in, I’ll put little notes in, I’ll type little questions in. Sometimes those are not real cute. Sometimes they're not flattering. Sometimes they’re kind of dumb. Sometimes they're dead ends. At their worst, they're deeply unexamined. I really thought about having a piece of paper next to me while I was working on this poem and writing it there instead of on the screen, because I wanted people to see where I got to, but I didn’t necessarily want them to see those things that happened in the midst of writing the poem. And I decided not to do that. I decided to type them into the software and to let them be there. And so again, I feel really grateful that Annelyse saw those moments as me asking, “Is this true, could this be more true?” And when I hear you talk about those three poems from All Its Charms that you gave as an example of failure poems and poems that are working through otherness and othering and whiteness and race and all of that, I think I hadn’t yet found a greater kind of courage to ask myself, could this be more true? Which is not to say, like, “And now I’ve achieved it, and now I can write those poems, and I can always ask myself that question.” I think, no, that’s just like a continuing practice that I hope continues to evolve and deepen, and there's always more work to do. But I think maybe that’s sort of the starting point of what is missing from those poems in the last book is the ability to really say, “Could this be more true? And if so, what could make it more true? How do I make it more true?” This poem was particularly challenging in that way because it involved a unique kind of attempt at imagining what is true and questioning what we have agreed upon culturally as being true of this historical figure who has been made myth and been used again and again and again by our country. And yeah, what could make it more true? And that was what I came up against again and again in its writing, and that was what was uncomfortable for me, and that was what yielded, I think, the most fruitful parts of the poem.

DN: Well, there's something I think really generous about how you frame failure both within your poetry but also out in the world. Speaking of your recent NEA fellowship, you talk about how you've been applying for 20 years to no avail, until now, until this latest application. Congratulations.

KK: Thank you.

DN: This latest application was with these new poems we're discussing, full of "female desire, sex, shame, masturbation, menstruation, the pitiful needs of a body in time, and a painfully complicated queerness." That winning with these poems felt like a victory in itself, given that you've lost out on certain literary opportunities explicitly because you wrote on these themes. You say you were even told point blank that your work on these subjects didn't have worth. Then you thank the NEA for reminding you that those who haven't believed in your poems were wrong, which I love. But in the face of being told you were wrong, you're also engaging with wrongness. As you've mentioned, you've wanted the latest collection to not feel like everything fits, that a wrong word or an image that doesn't belong could be part of this world. Which is maybe even an argument that this allowance for wrongness is what makes the poems right. The poem in Midst is not the only time you publicly allow us into the revision process to see the wrong versions of your poems. At Underbelly, you show us a draft of “Shooting Clay Pigeons After the Wedding.” You say in your commentary that there are three types of poems. The first come out nearly whole in a first draft. They are rare but the best poems you write. The second require countless drafts and are the majority of your poems. But the third is the rarest type, ones you've worked over and might have abandoned but couldn't abandon them even if you should have. You say they're never the best but often the ones you most treasure. That's something I'm curious to understand better. But in light of all I've now just said, I wanted to ask you about your second collection, one you distance yourself from in conversations about your poetry, sometimes even seeming to disown it altogether. When you learned that BOA Editions included it with your other work sent to me, you reached out just to let me know you feel far from this collection, perhaps that it was a misstep, I wonder, you said it's hard to read now because of your lack of compassion for yourself within it. But you've also talked—and perhaps this relates to my opening question about how one book engenders another—about how you felt that after finding your voice in your first book, in your second you somehow had the idea that the voice had to be different, that it had to then change. I don't know if you can place yourself in that moment of perhaps forcing a new voice and what resulted. But can you talk about this book in light of all we're talking now about failure? Do you see it as wrong, as a failure? And if a failure, is it a useful one or one that you wish hadn't become public?

KK: I think I was trying very hard in the writing of that book not to be a woman. What I mean when I say that is that I was trying to be smarter than a woman, more well-read than a woman, less ruled by my body than a woman, more head than heart than a woman, because all those things are inferior and have less worth and less value, especially in the academy, which is something I think I have felt from day one. I mean, that sounds silly. There are so many women poets who are body and heart—Sharon Olds, Ellen Bass. I mean, these are remarkable writers. Marilyn Hacker, Adrienne Rich—so much body, so much heart. So yet, how did I, despite that, somehow get the message that it was less than? I don't know, but I did. So I wanted very badly, I think, in that book, to distance myself from that, from that body and that heart. And that was very present in my first book. And I think I needed to prove, “All right, but there's more. There's more to me than that. And I can leave all that stuff that makes me a woman, I can leave that behind.” And so I tried to. And I think what I ended up with were, there are some poems in that book that I like, but there are others in there that are like false, echoey tombs, where a poem goes to die and were just to be dead. They're inauthentic, and they're trying to prove something that they can't possibly prove, which is that I'm not a woman. Because I am. By trying to prove that, I mean, they just come up wildly short.

DN: I'm so glad I asked you. That's incredibly, I think, helpful to hear for writers. You have a craft talk you gave called The Wonders of Worm Level Writing, which I want to use as sort of a transition to talking about another element of your work that we haven't talked about yet today. In your description of it, you say, "The Latin root of the word humility, humus, means ‘of the earth.’ So to humble ourselves inside the poem, to attempt to answer the question of what we've sometimes gotten painfully, harmfully wrong as we move through the world, is work that requires getting a little muddy. What might it be like for our poems to get down in the dirt, to put ourselves in our poems at worm level. In this class we will spend an intense week concentrating on writing towards the places in our poems where humility manifests itself as a clarity of vision of ourselves in relation to the world." The idea of worm level writing reminds me of your Native Species poem in your last collection that has the lines, "What hasn't been populated by trespassers, remade from the inside out? No wonder my body is finally doing the dirty work it's always wanted to, spiraling deep within itself to make from the wildness something that doesn't care if it belongs." I'd like to spend our remaining time talking about wildness and also wilderness, which is all over your work. Let's first spend a moment with form and wildness. You've talked about your love of syllabics, which is, I think, relatively uncommon in Anglophone poetry, but that you can also become too comfortable and safe, as you mentioned today in your 10-syllable, 14-line poems. You've also said, as another example, "As is so often the case when I'm writing something where the rhetorical stakes are high, this poem could only exist as a sonnet." When you were on The Poet Salon podcast about your last book, it was interesting as a listener because you spoke a lot about wildness, while at the same time the hosts were marveling at the containment of your form, with Dujie calling it a radical dedication to formal symmetry. But then Gabby seeing the messiness and wildness more in the thinking through and in the themes. I also think of the line by Seamus Heaney in the new book—the epigraph to the new book—"If self is a location, then so is love." Again, a dialectic between form and uncontainability in Heaney's line and your poetry at large, I think, a tension between the container and that which refuses the container. But as a way into talking a little bit about the more-than-human world, let's first talk about wildness in relationship to poetry and how and where you're seeing the wildness now.

KK: So when I am revising a poem, I always find it really useful to put it to received forms or to dramatically change the way that it's working on the page, either through syllabics or line length. Or in the Sacagawea poem, there are these numbered sections that interrupt phrases and sentences in the poem, which was something that I came to deep in the drafting process, not early on. It wasn't a conceit that I had conceived of from the beginning, like, "Oh, I'll have these interruptions." That was something that I landed at much later in the drafting process and was an experiment when I first tried it in the poem. And in the poem Greek Chorus, it's a long, very skinny poem with just a couple of words on each line. That poem was a sonnet at one point, a prose poem, a long-lined poem, a poem in syllabics, all of those things. Each time I would sort of take it through its paces in its new form on the page, I would discover something else that needed to change or happen in the poem. By doing that, I would realize that there was more compression available to me in a certain place, or the opposite, that I had room to lean more deeply into an imagistic or metaphorical moment. Or I would, by changing the line break, discover a moment of rhythm that I could press harder on or a music that I could make sing more clearly in the poem. So by taking it through these different manifestations on the page, I am searching for what its eventual, more permanent manifestation will be. But I'm also using each of those versions to work through and discover other moments in the poem that need more, or need less, from me. So that's the kind of, I don't know, experimentation in wildness, I guess, that is also combined with control. I mean, I love it. Like, control is, oh, in the drafting process, it feels great. Like, “Okay, great, I'm going to take this poem and now, yeah, put it into syllabics, or put it into that sonnet, or how can I break these lines so that this poem does work if there are only one or two words on each line?” That's this moment of sort of escaping into the game of the poem and the play of the poem, while also getting to feel like the all-powerful and almighty poet who has control over the whole thing. So that balance of control and play, but then ultimately, wherever it lands, making sure that through those sorts of exercises and steps that I've taken the poem through, that yeah, I haven't polished it to a shine. Like I said at the beginning, I'm very wary. And that's what I used to do. I would put it into a sonnet so that I could whittle it down and make it this skinny, no-fat, like a poem that only drinks protein shakes and then goes to the gym for two hours. [laughs] Nobody’s interested in that body. And nobody’s interested in that poem. Yeah, I don’t want to use that. I want instead to use those old familiar tools to make discoveries that work more like surprises, instead of using those old familiar tools to buff all the surprises out of the poem.