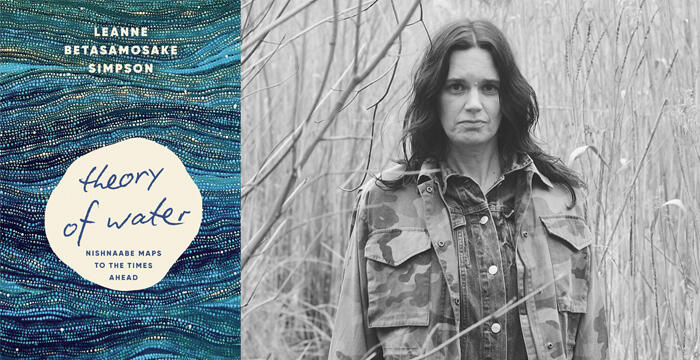

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson : Theory of Water

What would it mean for our writing, thinking, and living if we looked to land as pedagogy, or if we thought of theory as something embodied and kinetic? In Theory of Water Leanne Betasamosake Simpson takes us not only outside the academy, and away from our screens, but outside and into the world at large as part of a reconsideration of what and whom we consider teachers and mentors, of where and how we might learn and develop our thoughts, and of what the role of stories and storytelling might really be. Theory of Water ultimately explores what this reorientation might do, not only to our writing and our relation to language, but to our politics, our vision of a future world, and how we might arrive there together. Looking to water, to snow, to ice, to eels, to beavers, to bullfrogs, we explore what the more-than-human world can teach us about resistance and coexistence both.

For the bonus audio archive Leanne contributes a sneak peek at a song of hers, “Murder of Crows,” that will be on her upcoming album Live Like the Sky (which will likely be released some time this fall). To learn about the bonus audio archive and all the other potential rewards and benefits of joining the Between the Covers community, head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you in part by the recording label TAO Forms and their new album release entitled Revision. Revision is a collaboration between poet, scholar, 2020 MacArthur Fellow, and vocalist Fred Moten and the virtuosic double-bassist and improviser Brandon Lopez. The work of each of these perceptive and creative artists concerns itself with navigating the present moment, while simultaneously keeping humanity and sanity intact. Revision is a detailed studio recording which captures a full nuance of tone, both in Moten's voice and the exceptional range of sounds generated by Lopez on his bass. Revision is available on LP, CD, and download from TAO Forms, a label which presents great work from both established and next-generation devotees of the music. Today's episode is also brought to you by Katie Goh's Foreign Fruit, a bold and beautifully written memoir that begins as a simple curiosity into the origins of the orange and becomes a far-reaching odyssey. Heralded by Katherine May as "a sharp, sweet memoir of change, identity, and hybridity," and by Amy Key as "an encounter not only with the orange but with the reality of diasporic life in hostile environments," Foreign Fruit is simultaneously exploratory and intimate. Alongside the complicated history of the orange is Katie Goh's own story, one of growing up queer in a Chinese-Malaysian-Irish household in the north of Ireland and feeling at odds with the culture and politics around her. Yet over the course of the memoir, the orange becomes so much more to Katie than just a fruit. It emerges as a symbol, a metaphor, and a guide, encouraging readers to reflect on ideas of self, belonging, and the myriad forces that shape us. Foreign Fruit is out May 6th from Tin House and available for pre-order now. If you listened to the conversation with Omar El Akkad earlier this year, you may remember me mentioning to him the book of today’s guest, and how it is a touchstone book for me this year, a book that has helped me more than any other in recent memory to imagine an otherwise. One that upends what we think of as schools and teachers, and where and how our writing and thinking could occur and be in relation to. And how this reorientation can not only affect our art-making, but I also think our living altogether. Before we begin, I want to mention Leanne’s contribution to the bonus audio. As you'll soon learn, Leanne is also a musician, and for the bonus audio, she gives us a sneak peek of a track from an upcoming album of hers. The song is called Murder of Crows, and the album, called Live Like the Sky, will likely come out this fall from You've Changed Records. This joins an immense and ever-growing archive with contributions from everyone from Dionne Brand, Canisia Lubrin, Christina Sharpe, Naomi Klein, Isabella Hammad, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Natalie Diaz, Layli Long Soldier, Omar El Akkad, and many others. And the bonus audio is only one of many things to choose from if you transform yourself from a listener to a listener-supporter by joining the Between the Covers community. You can check it all out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. And now for today’s episode with Leanne Betasamosake Simpson.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today’s guest is the Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, writer, artist, musician Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. Working for two decades as an independent scholar using Nishnaabeg intellectual practices, Simpson has over 20 years’ experience with Indigenous land-based education. She studied biology at the University of Guelph, received a Master of Science in Biology from Mount Allison University, and holds a doctorate in Interdisciplinary Studies from the University of Manitoba. She’s the past Director of Indigenous Environmental Studies at Trent University and is currently faculty at the Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning in Yellowknife, which provides post-secondary education using an Indigenous land-based pedagogy. As a musician, Simpson has performed across Canada, often with her singer-songwriter sister, Ansley Simpson, and guitarist Nick Ferrio. Her albums include her 2016 release of story-songs, Flight, and her latest record, Theory of Ice, which was shortlisted for the 2021 Polaris Prize, nominated for Pop/Alternative Rock Album of the Year at the Summer Solstice Indigenous Music Awards, and was listed number one in Exclaim!’s 31 Best Albums of Anyone. Simpson is the editor or co-editor of Lighting the Eighth Fire: The Liberation, Resurgence, and Protection of Indigenous Nations; This Is an Honour Song: Twenty Years Since the Blockades, an anthology of writing on the Oka Crisis; and The Winter We Danced: Voices from the Past, the Future, and the Idle No More Movement. And Simpson’s own books include Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence, and a New Emergence; Islands of Decolonial Love: Stories & Songs; and This Accident of Being Lost: Songs and Stories, which was the winner of the MacEwan University Book of the Year and named a Best Book of the Year by The Globe and Mail, The National Post, and Quill & Quire; As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance, the novel Noopiming: The Cure for White Ladies, shortlisted for the Governor General's Literary Award for Fiction, and most recently Rehearsals for Living, co-written with Robyn Maynard, with the foreword by Ruth Wilson Gilmore and an afterword by Robin D. G. Kelley. M. NourbeSe Philip says, "In Rehearsals for Living, two women, one Indigenous, the other Black and African-descended confront their shared yet different experiences of colonialism. Unflinchingly, Simpson and Maynard weave their ideas, thoughts and reflections and their deep caring for community and society through the network of issues that impact us today. Rehearsals for Living is fundamental to understanding the interlocking, founding crimes of the Americas; necessary for remembering the many erased histories of the on-going struggle for justice, and altogether indispensable to those wanting to create possible solutions." Leanne Betasamosake Simpson is here today to talk about her latest book, out from Haymarket in the U.S. and from Dionne Brand's Alchemy at Knopf Canada, called Theory of Water: Nishnaabeg Maps to the Times Ahead. Here are thoughts about Theory of Water from three past Between the Covers guests. Christina Sharpe says, "Placing her body on the shore, on ice and snow, in water with cattails, bark, bullfrogs and more, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson's attentive and scalar thinking demonstrates that what we do on a small scale is how we exist at the large scale." Billy-Ray Belcourt adds, "Simpson shows through an analysis of snow and water that already codified in Nishnaabeg philosophy is the blueprint to another world, one where solidarity in revolutionary struggle is always possible. A beautifully written ode to our capacity to resist state violence and imagine otherwise." Finally, Omar El Akkad says, "No writer in recent memory has more thoroughly rearranged my moral compass than Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, and no book brought me more solace than Theory of Water: Nishnaabe Maps to the Times Ahead. Amidst the cascading calamities of colonial and capitalistic violence, in which the prevailing power structures depend so fiercely on our diminished capacities for care and attention, Simpson has written an essential work on love as methodology, on what it means to stand in solidarity with one another and with the earth that sustains us. This is more than just an imagining of something better, but a reminder that better has always been here, has always been possible. A book of immense regenerative power, written by one of the few truly incendiary, indispensable writers working today." Welcome to Between the Covers, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson: Thank you so much. It's an honor to be here.

DN: Well, it isn't coincidence that Theory of Water opens with you out on the ice and snow, contemplating your own history as a skier—something you've done since you were two—and also about the Territorial Experimental Ski Training Program in the 1960s that provided an escape for Native peoples from the abuse of residential schools. And perhaps in a similar spirit, you say in your words that "when it was icy, I could fly." That all your thinking happened out on the trail. That you wrote and skied, making connections on the trail that you could never make in front of a computer. You say explicitly that your body of work exists the way it does because you removed yourself from the academy, and that this book comes through an escape hatch, one that seems to rhyme, perhaps, with this ski training program as an escape from the residential schools as well. And this is a long-standing belief of yours. If we go back to 2014, your piece Land as Pedagogy argues that a resurgence of Indigenous political cultures and nation-building requires a radical break from state education systems and argues for a reclamation of land as pedagogy. So this feels like an important place to start: both hearing more about your writing and thinking process away from a desk while out on the land, but also about why this radical break from academia is important.

LBS: I think the radical break from the academy was important for me because I had a lot of difficulty fitting my intellectual and artistic and creative process into the boxes of the academy. So I had trouble confining my thinking to a peer-reviewed academic paper and those conventions. I had trouble coming up with an idea and doing a proposal or a prospectus and then writing the book. Whenever I did that, that was a guarantee that that book would not get written. So I really needed to find a way, I think, of being able to protect the part of me that can think outside the box and that can create, and that, for me, was outside of the academy. So that’s one answer to that. Another answer is that I really fell in love with Anishinaabe thought and my own culture and my own land, and I wanted to place that at the center or the spine of my practice of not just of writing and thinking, but of my life. And that meant spending a lot of time on the land with elders, with elders and my kids, or with elders and students, letting elders sort of lead the way and being attentive to how they teach, and how they're almost a conduit or a facilitator for how the land teaches. And so doing this for a couple of decades really, I think, consolidated this process for me. I was also always very, very involved in sports, but I was never very good at sports. [laughs] And I think part of the reason I was never good at sports is because I was writing poetry in my head or I was thinking of ideas. Whenever my body is in motion, that's when I get a lot of ideas or that's when I can work through things like writer's block. And so me on the ski trail is me stopping and thinking and making notes on my iPhone or making connections that I can't seem to make at a desk inside an office on a computer. When I go back to Anishinaabe thought, though, and when I go back to our origin stories, this is all sort of very embedded in how knowledge and storytelling and sharing of that knowledge, so that audiences and communities can feel like they belong to the stories. That's all sort of part of a bigger project that I love to be in the middle of. I think when I was thinking of the territorial skiers in the north, I was thinking about how sometimes I feel free when I'm out on the land running or skiing and I sort of lose that little bit of awareness of where I am and I start to be able to think outside the confines of the present moment and I know that Indigenous people often would escape to the bush as a form of resistance, in a way of reconnecting and regenerating themselves so that they could go and face the violence of colonialism. And so it did seem like a good rhyme to start the book there.

DN: One paragraph in that 2014 essay that I particularly love reads, “Nanabush is widely regarded within Nishnaabeg thought as Spiritual Being and an important teacher because Nanabush mirrors human behavior and models how to come to know. I think it’s important to point out that Nanabush does not teach at a university, nor is Nanabush a teacher within the state school system. Nanabush also doesn’t read academic papers or write for Decolonization, Indigeneity, Education & Society,” which as an aside is where this article I'm reading from was published. “Nanabush is fun, entertaining, sexy, and playful. You’re more likely to find Nanabush dancing on a table at a bar than at an academic conference. If Nanabush had gone to teacher’s college, Nanabush would have been fired in the first three months of his first teaching gig. This is precisely why Nanabush is an outstanding teacher – Nanabush not only teaches me self compassion for the part of me that may dance on bars in celebration of life and love and all things good, but Nanabush comes with inevitable contradictions held within the lives of the occupied. Nanabush also continually shows us what happens when we are not responsible for our own baggage or trauma or emotional responses. The brilliance of Nanabush is that Nanabush stories the land with a sharp criticality necessary for moving through the realm of the colonized into the dreamed reality of the decolonized, and for navigating the lived reality of having to engage with both at the same time." And in another place in that essay, you talk about the word theory and how theory within Nishnaabeg thought is generated and regenerated continually through embodied practice. That theory is woven within kinetics, spiritual presence, and emotion. That theory is contextual and relational. So before we talk about water and the theory of water, let's just spend a moment with what you mean by theory, and by "theory is kinetic," especially given that you cite explicitly ice and snow as your collaborators in this regard.

LBS: Yeah, that’s a good question. I think that one of the positions—the ways that Indigenous people and Indigenous thought has been positioned within a colonial framework—is as less than. Our knowledge is less than Western science and Western knowledge. We are not as smart as non-Indigenous people. And so early on in my career, I became very interested in learning how—or trying to learn how—to think inside Anishinaabe thought. And I became very interested in thinking about Anishinaabe theory. So I started thinking, "A theory is an explanation for something." And how does theory operate within Anishinaabe thought and within Anishinaabe communities? The first thing that I noticed is that it operates in a very horizontal fashion. It's not something that is just for professors or theorists in ivory towers. It’s something that’s for everyone. It’s for all of our people. And it requires an engagement with story, an engagement with life, a certain kind of presence, and it requires an internal journey, I think, a commitment or responsibility to make meaning and to find meaning in the context of one's life. And so that’s sort of, in my culture, the responsibility of someone who is listening to stories or reading stories: to find that meaning. That became very interesting to me, to think of theory as something that’s communal and a communal meaning-making process. And it became interesting to me to try to think through our present moment through that lens. What I came to learn very, very quickly is that I couldn’t do that at my computer and through reading, because the people who are experts on that, who are elders, who are language speakers, teach through embodied practice. And this act of going out on the land, setting up camp with a group of students and a group of elders, is a way of embodying that theory together. And as you sort of make something together on the land, it’s incredibly generative, in terms of learning, in terms of what you’re learning and how you’re learning. And connecting that then to the stories that one’s being reminded of, of how our ancestors traveled on a particular lake or their interactions with a birch tree, sort of deepens that practice and deepens that understanding. And so as a writer, I think I was always trying to figure out how to communicate the depth and the thickness of our knowledge and our stories through writing in English. And that’s, I think, required some creativity on my part, some expansion of genres and disciplines in order to be able to communicate that. And I don’t know that I’ve ever been able to do that successfully. I think that’s sort of the struggle, a struggle that’s common to Indigenous writers and Indigenous academics right now.

DN: Well, when Natalie Diaz came on the show for the first part of our almost five-hour conversation—

LBS: Beautiful. [laughter]

DN: Her last collection focuses on water as well. And we talked about how the Black diasporic experience so often is seen through water, and the Indigenous experience through questions of land, and how she was working, I think, against a reductive one-to-one correspondence in this way. In her piece The First Water is the Body, the body and the land are one and the same. And the river is a body, and the river is in her body. But thinking about your Land as Pedagogy a decade ago, and now your book Theory of Water, which may or may not be two ways to say or look at the same thing, talk to us about what centering water does? What changes or is highlighted or foregrounded when moving from land as a lens to water as a lens?

LBS: Early on in my career, I was very focused on land. As many Indigenous writers and Indigenous academics and Indigenous people, our land is incredibly important to us. And because I think that I was coming to those questions through this Anishinaabe theoretical lens, I was adding water into that, so water is included in land. Then I started to think of land as a network, as a cascading set of interconnections and interdependencies that crossed different species, that crossed different kinds of humans, and that was propelled, I think, by what we call in my culture mino-bimaadiziwin, or this continuous rebirth. So it involved cycling, it involved interdependence, it involved reciprocity, and I started to see it as this complex network that was expanding through time and space. And that’s a very different understanding of land than the one I would inherit from settler colonialism, that is a territory, that has borders that are guarded, that is owned by people, that is property. And so using the word "land" in English, in our current reality, invokes property, it invokes borders. And I was talking about something very different. And so I tried to sort of articulate that, as we have always done, and it was a beginning. And then I kept thinking of this more deeply and more deeply. In my culture, water is very, very important. And it’s often, in our ceremonies, in the realm of women. I think that because part of my work and my life has been to really trouble the gender binary and undo the gender binary, I didn’t participate in a lot of the water walks, and I was more reluctant to get involved with the “water is life” sort of activism. But as I came to it in my own time, I started to think about what I could learn from water through its embodied practice. Here’s the global water cycle that touches every form of life, every geography on the planet. Here is a being that’s been here since the very beginning and that will exist long after I exist. Here is Nibi that can change from a solid to a liquid to a gas, that’s constantly transforming. Here is water that is seemingly not powerful, and then you see a massive blizzard or a tidal wave or running water washing away at a rock for tens of thousands of years and then cutting an arch or a chasm or a rupture. So I started to become focused on water as a teacher, as a collaborator, as a being that was teaching me to—as Fred Moten says—violate my home spaces. It’s inside of me. It’s outside of me. It’s connecting me to Palestine. It’s connecting me to Sudan. And it’s something that I’m interacting with every day. So it suddenly became this powerful teacher and a way of reorganizing the way that I was thinking about the world. And I think that was the motivation, I guess, for Theory of Water. It also requires me to think outside myself and to think outside my people, because my territory is not attached to the ocean. So then I need Christina Sharpe to understand the Atlantic passage. I need Black feminists and what the ocean means. I need the Kanaka Maoli to understand what the South Pacific means. I need the Māori. I need desert people to understand what a lack of water does. It requires a collaboration that’s much bigger than me and much bigger than my people.

DN: When Omar El Akkad was on the show a couple of months ago, I was talking to him about how important his new book felt as a diagnostic, a book that’s been described as a breakup letter with the West. But I was curious to understand better what he meant by the negative resistance that he suggested, what he called a “walking away,” which didn’t necessarily mean moving anywhere else. I was curious because I was having trouble picturing how to walk away while remaining deeply enmeshed and complicit within the system. And I’ve long wondered and debated within myself whether it’s enough to know what we are saying no to and what we’re moving away from. For instance, I think of the routiers and Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return, these oral songs that served as navigational maps, and how, for her, it feels like these songs move the marooned diaspora away from centers of violence, perhaps toward a gathering place elsewhere. But as I discussed with Dionne, the gesture seems to be one of escaping and exceeding what one is escaping. But as I was telling Omar, reading Theory of Water felt like a landmark breakthrough moment for me in my own understanding. It’s the first time I felt like I could really imagine and picture what this world we would be walking toward could look like, and also what creating that world looks like as well. As a first step toward exploring this together, the world to fight for and how we can be part of that, I wanted to first talk about the creation story you share in Theory of Water. Many of your books and essays and speeches center and orbit around a story. The story you tell in your anti-scholarly essay, Land as Pedagogy, you call that story a theoretical anchor in that essay. And it feels to me like the creation story in Theory of Water might be a similar theoretical anchor for the book. The elements of the story that most stayed with me have to do with the inevitability of imperfection and failure, and/or the limits of individual action and the power of collective action, but in a time frame that exceeds an individual life, the Creator Spirit who creates the world, that world goes awry. He gets assistance from the Sky Woman for a second try, but that is also flawed. Then at some point, water—Nibi—helps by flooding the Earth entire. Then we have all these different animals that are stranded on the back of the turtle. There's no land, and each is diving down to try to bring up dirt with them, often dying in the process as they do, even if they float up with a flipper full or a paw full of dirt, not necessarily seeing what comes from all of their collective effort. But I'd be interested in hearing what about this story of repeated failed creations by both spirits and animals compels you to possibly be anchoring your book in this way. But also, more broadly, if you could talk about the role of story. For instance, when you say, "Nanabush stories the land," which feels like something important or central to this practice.

LBS: Yes. I think when I say Nanabush stories the land—if you're Anishinaabe and you know a lot of Nanabush stories and you're out on the land—the forest, the rocks become almost a mnemonic device to remind you of those stories. So when you see Nanabush’s footprints on the rocks in the Canadian Shield, there's a story about that. That links to one of the creation stories where Nanabush walks around the world, and I've used it to talk about Anishinaabe internationalism. When you see sphagnum moss, there's a story about how Nanabush’s brother was not able to contribute to the community, and no one could figure out why. And so, over decades, the people carried him and tried to help and tried to get him to be able to give something back. And eventually, the spirits changed his brother into the sphagnum moss, which was very, very useful to the community. So there are all these reminders on the land of stories. And I've often said that the forest or the land, it's like a library, but it's more like a mnemonic device. It's a reminder of all of these connections and all of these stories. Now, what was the first part of your question?

DN: About the creation story that perhaps serves as an anchor for Theory of Water.

LBS: Right. So, origin stories and creation stories are the big sort of meta-theory in Anishinaabe thought. I think a lot about them because they are often stories about how the world is made or how Anishinaabe people have to figure out how to weave or knit themselves into the world that was already made. Because, like you, I'm thinking all the time about alternative ways of living together on the planet if one refuses racial capitalism and heteropatriarchy and colonialism and imperialism and all of those things. I'm interested in figuring this out. One of the things that I think that I've learned from my people is that Anishinaabe people got up and they made things. We didn't rely on institutions in the past or banked capital. We got up and collaboratively made life and made the systems of life, whether that was our system of spirituality, our artistic practices, our transportation systems, our foodways, our clothes, our housing. All of these things were creative practices that were done collaboratively. When I look back to those creation stories about how the world was made, it was never made by one person. It was never made the first time and worked perfectly. It was always a struggle. Making the world was always a struggle. Figuring out how to live in a good way with millions of other forms of life was always a struggle. I often think in this present moment, where we have genocides in Gaza, in Sudan, and Congo, where we've got increased fascism in the global north, where a lot of my friends and comrades are really struggling with some horrific violence, I think of us sort of all on the back of that turtle trying to figure out how to live differently. It's not Leanne's ideas. It's all of our ideas together and figuring out how to regenerate, how to take care of each other, how to meet the material needs of the life that we're on the back of the turtle with. I think there's a lot in the book. Maybe they weren't even thinking of making a world right now. Maybe they were just thinking of meeting the needs of the people they were in commune with. Anytime we get together—whether it is at a protest on a Saturday in front of a Tesla dealership or whether it is in a land-based practice—when we get together and we make something together, that is a site of regeneration. Or as Ruth Wilson Gilmore says, that is a rehearsal. That is us rehearsing and scaling up and figuring out collectively this next world. For me, those are really, really powerful actions and powerful sites. And they're a way of generating theory from practice. That's the kind of work that I think gives me hope. Not that we don't need people who can diagnose the present moment and who can link that to the history of fascism, and who can link that in a way, I think those people who do that work are very, very important. But I guess the poet and the dreamer of me is always on the back of that turtle trying to imagine a different way of living. [laughter]

DN: Well, we have a couple questions from others that aren't exactly the same question—maybe not the same question at all, I'm not sure—but to me they feel like two questions reaching toward a similar place, so I'm going to play them together in the spirit of these very different animals sharing the turtle’s back and risking on behalf of each other for the future of everyone. Of course, if they do seem different to you, do feel free to speak to them as separate questions, too. The first is from Omar El Akkad. He’s the author most recently of the book One Day Everyone Will Always Have Been Against This, the book he came on the show to discuss, of which Christina Sharpe said, “Here, language does what we need it to do: it clarifies, it condemns, it names, it grieves. Here, too, is a lexicon for what might survive this. Devastating and scathing; you will want to read, will want to have read, this book.” The second question, which I’ll play before you answer either of them, is from someone who you discuss within Theory of Water, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, who describes herself as a queer Black troublemaker and Black feminist love evangelist and an aspirational cousin to all sentient beings. Her most recent book is Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde, but she also has a very water-centric book as well called Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals, of which Dani McClain says, “Alexis Pauline Gumbs pushes us out of our comfort zone and into the sea, where other species are moving and mothering in ways that can teach us how to survive.” So here are kindred questions for you from Omar and Alexis.

Omar El Akkad: Hi, Leanne. I have to admit, when David first asked me to submit a question for this episode, it seemed like the perfect way to communicate with you because I think every time we’ve been in the same room, I’ve been far too intimidated to actually approach you and say anything. So being able to communicate with you from a distance probably works well for someone as insecure as I am. I don’t know that there’s a writer alive whose work has been more comforting or instructive to me than yours. I was sitting here thinking of all of the things I wanted to ask you, about This Accident of Being Lost, which is my favorite book of the previous decade, about your work with Robyn, about this new book. I think I’ve haphazardly settled on a question that I’m not even sure relates to craft or personal methodology, but it has to do with something that I find in all of your work, which is this incredible obligation to care. Every sentence, every concept, everything you approach has this immense duty of care. I guess I wanted to ask you how you go about protecting that capacity for care, especially in a world where so many of the dominant systems of power seem to be predicated on this kind of ingrained carelessness, this inattention, this lack of desire to treat something with the respect it deserves. So I really just wanted to know how you go about protecting and cultivating this care, this obligation of care that runs through all of your work that I’ve ever read. Thank you so much.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs: Hello. It’s Alexis Pauline Gumbs. I am so grateful for your work at all times and in this time. I wanted to think of a really smart question, and then I wanted to think of a really beautiful question, but then I just had to be honest that my question for you is what’s on my mind and on my heart as I watch colonizing resource wars ramp up and continue, which is something that you speak to in this new work, in Rehearsals for Living, in really all of your work. But I would love for you to talk about the wisdom that you have for how we protect the sacred, including water. Or maybe that’s not the formulation. Maybe it’s how the sacred protects us. Maybe the word protect is not doing what I want it to do, but I’m thinking about the sacred, the sacredness of water, and how to honor what we love when so much energy is being focused on turning everything into an extractable resource. So that’s my question. It’s a sincere question, and of course, it’s not for you only individually to answer, but I respect and admire you so much as a guide, and I feel like even the slightest gesture from you could be so clarifying and illuminating for me and for us. So that’s my question. Thank you always.

LBS: Wow. Those are such beautiful, beautiful questions. That was very, very moving just to listen to the questions. I don’t have trouble trying to think up good answers to both of those. I think for Omar’s question, at the center of Anishinaabe life is these seven teachings that are often called the Seven Grandfather Teachings or the Seven Ancestor Teachings. I wrote about them as a first try in Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back. I remember talking to Doug Williams, who’s the elder that I worked with a lot for a couple of decades, and asking him in his office at Trent University how you say “Seven Ancestors” or “Seven Grandfather Teachings” in Anishinaabemowin. And I thought that it would be a direct, literal translation, and he thought for a long time, and then he said, “gookom dibaajimowin,” the grandmother stories. I asked him, “Why do you call them that?” And he talked about how that’s how his grandmother called them. She called them that because children would learn these teachings—about love, about bravery, about honesty, about truth—from their grandmothers. Their grandmothers would tell them specific stories about people in their family who did an amazing job of embodying those teachings. I thought that that was an amazing system of care. So almost wrapping young people in this blanket of stories that are seeds that they can carry with them through their life. They can think about, pull them out, find meaning, watch the meaning shift, but it also connects them to their family. It shows them leaders in their family, lots of different kinds of leaders. It shows the best parts of people that they’re growing up with. I really loved that teaching and I started seeing those teachings not really as teachings and not even really as laws, because sometimes they almost get referred to like the Ten Commandments, like they’re kind of a rigid, “You have to follow these laws or you’re going to get struck down by lightning.” But what these are is really a very gentle system of care. I work a lot in the North with Dene people who also have a similar set of Dene laws, which are about taking care of each other on the land. So in my work at Dechinta last June, we brought my comrades Glen Coulthard and Kelsey Wrightson brought a group of Black, Brown, Palestinian, Indigenous folks to a camp outside of Yellowknife on the land for a solidarity gathering. But we knew that each one of the people that we had invited had had a very difficult year, organizing, speaking out, going to protests, surviving genocide. So we thought very carefully with our team of elders and with our land-based team about what this group of people needed in this particular moment in time. As we went through this week together, it became care. We fed them really well. We made sure everybody had a comfortable place to sleep. We tanned hides together. We fished together. We did ceremonies together. We rested. We laughed. We had fun kind of canoeing around together. And it became really, really clear to me how important taking care of each other is, far more important than the papers that we didn’t actually ever read to ourselves or each other. [laughs] But it became important because it bonded us to each other. Because we created relationships. We created relationships of trust and intimacy. We created a community. We built a community together and then lived in it. So yes, it became this generative site of knowledge. But also, I think my hope is that we all kind of came out of that gathering feeling slightly better than when we went in. That’s actually what I want for my readers with Theory of Water. I hope that people are able to find a little bit of solace, take a breath, and come out just a little bit better. I think it is very important for writers in particular to find ways of protecting the parts of themselves that can create. Because I think this world right now is really hunting down that kind of intimacy, that kind of vulnerability, and I think it’s important to find ways of protecting that, for sure. Then Alexis’ question is pretty similar, but I think the way that we protect the sacred is we belong to it. I think that by belonging to water, and water belonging to me, we create this reciprocal relationality that’s a system of care and that’s nurturing, and that I think can—in times like these, at least for me—give me the wherewithal to go back out into the world and fight. It’s like a power-up. I think that it’s important for all of us in this moment to find those things that calm us down, fill us up, make us feel connected, and give us the ability to dream beyond, even though we’re in this current situation with so much violence and so much death.

DN: Well, one of the ways you describe water in this book—one of the many ways you describe water in this book—you say it’s “iterative, resilient, transformative, interdependent, decentralized, a vessel for multitudes, always creating more possibilities, an emergent theory of internationalism. It works with and asks us to embrace uncertainty, multiplicity, adaptation. It’s within us and connects us to all forms of life.” But you also talk about something that I think speaks to what you’ve just talked about, this question about bonding and collectivity and belonging, called sintering. I agree with Christina Sharpe when she says, “Simpson gives us the word sintering--which is what snowflakes do to bond in place. It is joining and deformation; it is transformation; it is an ethic of how to live. Sintering should be in all our vocabularies for how to see and imagine ours and each other's linked presences in the world.” Talk to us a little bit about sintering, what exactly it is and what you see it modeling?

LBS: So one of the things that makes Theory of Water different than my other works is that my longtime mentor and Elder Doug Williams has now passed away. And so I don’t have this person—this Majisagik Anishinaabe person who knows more about everything than me—to go to all the time. I’m missing this mentor. I’m missing this teacher. I’m missing this kind of parental figure, friend, comrade. We did a lot of stuff on the land together. So during the pandemic, I volunteered to become a groomer at the ski trail that’s close to my house, and I was out on the trail a lot of times in the morning packing down the snow so that skiers could come and ski on the trail. And one of the things that groomers pay a lot of attention to is sintering. It’s this transformation that snowflakes go under as soon as they arrive on the land from the sky world. And it’s not a melting process, it’s a slow deformation where the kind of branches of their crystals round, and they become bonded to each other. So if you're from a place where there is snow, usually when the snowstorm happens, the snow is really really fluffy and then it takes 24 to 48 hours for it to kind of settle and to settle into a snowpack, and that's when the snow becomes sintered. When the snow starts to melt in the spring, the sintered snow, the snowpack will stay on the trail a long time after the snow, the other unsintered snow melts. So I started to think about this not in terms of grooming pretty quickly, [laughter] but I started to think about this in terms of communities and relationships and solidarity and about how this bonding to each other was a very important step, I think, in Indigenous resistance in the past. When I think of kind of my ancestors in the 1700s and the early 1800s, when they were engaging in organizing politically, they walked around and visited with other camps and other communities, often like a very far distance, they shared food, they got to know each other, they developed these bonds of trust. I think that that's what those snowflakes were reminding me and were teaching me. So I started to think of this scientific process, Western scientific process of sintering in a different way. It spoke to me sort of in that moment that being attentive to our relationships in political contexts, when we're organizing, when we're thinking about things like solidarity, are a way of strengthening movements and strengthening our forms of resistance.

DN: Am I right to think that the significance of sintering being different than melting, that the snowflake, while it's not exactly the same when it's sintered versus unsintered, it is still remaining itself in some sense within the collective? So it's bringing something of itself rather than disappearing as part of joining. Is that right?

LBS: Yeah, that's right. I think that that's a really important part that reminded me a lot of Anishinaabe political traditions, where you can share territory and you can have separate sovereignties and separate jurisdictions, where we think of beavers and moose as being nations that we share time and space with. So this sintering process, the snowflake is still a snowflake. It's in slightly different formation, but it's bonded to its neighbor in a way that doesn't destroy itself, and it doesn't destroy its neighbor. It's not a transformation like melting. It's not a complete change in form. It's a slight change in form.

DN: Well, much of what Omar's book looks at is liberalism's relationship to fascism as an enabler of it, despite it seeing itself as an opposition to it, it often serving as a cover for it. Thinking of this, it feels similar to your Land as Pedagogy essay—calling for a radical break from institutional education—the Theory of Water is calling for a radical break from the state or the nation-state and appeals to the state for recognition as the main mode of relationship to the state. I was hoping, as a preface to us talking about this together, we could hear a section of Theory of Water that's sort of about this.

[Leanne Betasamosake Simpson reads from Theory of Water: Nishnaabe Maps to the Times Ahead]

DN: We've been listening to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson read from Theory of Water: Nishnaabe Maps to the Times Ahead. I've always felt sort of stuck at imagining what we replace the nation-state with if we only look at pre-nation-state examples within a European context. Feudal kingdoms or princely fiefdoms are not literally appealing or alluring alternatives to sort of mobilize around in my mind. But Theory of Water puts forth a vision which I think shares a lot of qualities with anarchism, no hierarchy, or authoritarian power, no police, no coercion, and also an emphasis on mutual aid and solidarity horizontally. But one way an Indigenous vision seems to me to differ from non-Indigenous anarchism is that there actually is an authority or a superstructure or a law that one is beholden to—and of course push back if I'm totally wrong in all of this—and that that superstructure or authority is nature. That nature is what negates the state. For instance, when you talk of water, you say water continually violates home spaces of everything on the planet. That it always escapes the container and also never gives up, which both seems to evoke a mode of resistance, but also a mode of harmonious coexistence. It seems like Robin D. G. Kelley is hinting at this in his blurb for your book when he says, Karl Marx wrote, "Karl Marx wrote, 'To be radical is to grasp the root of the matter'; for him it is man. Leanne Betamosake Simpson tells us that to be radical is to grasp the source of the matter: water. She is right, and shows us why in this poignant and poetic meditation on the power of water as Life. The first victim of colonial/capitalist exploitation, water is also the first line of defense, and our most important site of (re)creation. If we are serious about decolonization, we need a theory of water." So his displacement of Marx's man with water and having a theory that decenters the human more broadly makes me think of you saying that your ancestors didn't build a world, but instead built a coalition with plant and animal life, where they wove themselves within a world or sintered themselves into an existing more-than-human fabric. Also, how you mentioned that in the north the word "people" is not reserved for humans. I realize I may be going astray or mischaracterizing all of this, but I was curious about your thoughts around this distinction that I'm making between, say, the European tradition of anarchism and how indigeneity both shares a lot of qualities with it and also perhaps has a significant distinction from it.

LBS: I think that my take on anarchism would be a grounded anarchism coming from grounded normativity—to use Glen Coulthard’s term that I sort of expanded on—and as we have always done. Certainly, some Indigenous people, some Anishinaabe people, would see the land or nature as the law, or natural law. For me, when I think of the planet as being a collaboration made up of diversity of ecologies and species and ways of knowing and ways of being, it becomes very, very complex very, very quickly, almost more complex than I think any one human or one living being can comprehend. So we become interdependent upon each other because we all have a piece of the knowledge. We all have a piece of the practice. That's sort of the container, or that's the network within which we have to dream and build the alternatives. We have to figure out how to knit or weave or sinter ourselves into that existing ecology. But I don't see it as an authoritarian sort of entity, although it certainly can be. If you're not careful on the ice, you can fall through and lose your life. There are some endings because it's a powerful and complex system. But I see it as a belonging and I think I think of myself as a body as a node in the network of creation. I am made up of the relationships that I'm in. I am made up of the relationships that I'm in, and that's the container. That's the authority, if you will. So I think it's a grounded authority to use Shiri’s term, and I think it dovetails and it's related to European traditions of anarchism, although I would say it's a grounded anarchism.

DN: Well, we have another question for you from another. This one is from Past Between the Covers guest, Billy-Ray Belcourt, who came on the show to discuss his amazing, unclassifiable novel, A Minor Chorus, a novel he's sometimes referred to as "auto-theory." Since then, he has written the story collection Coexistence, of which author Claudia Dey says, "This book is a feat of beauty and compression, every sentence reinventing the reader. It's like entering a quiet room or a secret lake. It's about our coexistence with lovers, kin, enemies, but also our coexistence with desire, solitude, and an intelligence that in itself is a form of hunger. Language is solace, language is light. Belcourt is the rare writer who composes from, to, and because of the soul. It's been some time since I loved a book so deeply." Here's a question for you from Billy-Ray.

Billy-Ray Belcourt: Hi, Leanne. Congratulations on your new beautiful book. My question is: So in the book you write, "Worldmaking requires love, kindness, and care. It requires collectivity and relationality, and it is these practices that generate the knowledge needed to move on to the next step." I'm curious about when and under what conditions you first began engaging with the notion of world-making. How did you arrive at the concept? Or in other words, what is your genealogy of world-making? Thank you.

LBS: Another really great question. I've been thinking about world-making for a very long time, but through the lens of these Nishnaabe origin stories. As a parent, I wanted my kids to grow up with as many stories from their culture that I could fit into them. Of course, kids are sponges for stories, so they really led me into this body of oral stories around origins of different components of life. Anishinaabe people have at least four different origin stories for the making of the world, and some people say seven. So after I sort of ran out of oral stories to tell my kids and family stories, then I started to look in archives and in journals—anthropologists from the time of first contact—and trying to tell those stories not in a colonial sense, but decolonizing the versions that I was finding and telling them back into the context of my culture. So that's one kind of genealogy of that. The other part of that I think is doing this land-based work where you're constantly going out on the land with a different group of people, led by elders, and you're building a mini-community, and you're kind of doing it over and over and over again. That led me to the realization that Anishinaabe life pre-coloniality was a lot of making, a continual embodiment of those creation stories. Moving camp, every season, every different land-based activity, you are engaged with a different set of living beings. You know, in the sugar bush, you're working with maple trees. When you're harvesting wild rice, you're on the lake working with manoomin. That really made me understand that world-making isn't something that you just do when the current world falls apart. It's something that you do as a daily practice. Part of that daily practice is caretaking. Part of that daily practice is making good relationships, meaningful relationships, respectful relationships across difference. So it started to dawn on me that world-making as a practice, as a way of being in the world, is something that I see Indigenous artists doing and holding on to. I see elders doing it, and I see movement people doing it in terms of solidarity. So gaining skills in your daily practice of life, of how to forge systems of care and understanding and meaning across difference, became, I think, a really powerful way of being in the world.

DN: Well, thinking of genealogy, it's important to mention, I think—and you already have—your mentor Doug and how this book is, in a way, an homage to him and also an elegy for his passing, I think the part of the book that perhaps I think about the most is you retelling the story about Doug and the bullfrogs. You talk about how much Doug loved to hunt bullfrogs, and not only how between 75 and 90 percent of the wetlands in southern Ontario have been destroyed, but how much of the land where one might hunt bullfrogs is a patchwork of private property owned by settlers, and how the tourist lodges are always surveilling Native people trying to fish or hunt in any way. How Doug ultimately decides to fight for his people's right to hunt bullfrogs in court. In the end, he wins this right legally. But even though going forward with this long legal battle to gain this right, I think, is evidence of his love of this activity, once he achieved the right to hunt bullfrogs, he would never kill one. Not even a single bullfrog, because the frogs were so beleaguered as a nation. This, to me, more than anything in the book, helped me to understand, I think, what it means to knit oneself into a world that's not just a human world. So the grounded anarchism alongside plants and animals with mutual consent and mutual aid. I don't even know that this is a question, but I wondered if it sparked thoughts. Because this dynamic, this assertion of rights, but then also a recognition of the health or the lack thereof of this other nation, and the impact those rights, if executed, would have on them, seems like this really great encapsulation of something that you're reaching toward in Theory of Water.

LBS: I remember really clearly—probably 10 years ago, maybe 20 years ago, probably both—asking Doug to take me back to that lake to canoe and to hunt bullfrogs. Because the way that they hunted bullfrogs was pretty unique. And not all Anishinaabe ate frogs and snakes. And one of the reasons why my people were eating them was because of the Williams Treaty. It wasn't really a treaty. It was a trick and a fraudulent endeavor. But if you think of it as a treaty, it was the only treaty in Canada that took away our hunting and fishing rights. So my people had to exist for almost 100 years not being able to have access to our traditional economy and our traditional food, which meant our people were forced into sort of a state of poverty. I remember my grandmother eating things like porcupines and squirrels. And talking to Doug about this, he was like, “Well, I was always wondering why my people weren't eating moose and deer and the cool things.” [laughter] He explained to me, it was because of this. It's because we had to figure out ways of feeding ourselves out of the eyes, out of the surveillance of the game wardens. So I, as a form of resistance, really wanted to learn how to hunt bullfrogs. I wanted to reenact this. He said, “No, I would love to teach you that, but we can't do that because the frogs are struggling so much right now.” So that was a very important lesson to me. Because it would have been a beautiful day. That would have been a really, I think, a way of sort of honoring the struggle that Doug had gone through in getting arrested and taking this to court and fighting and winning this very important case that then brought our knowledge into the legal system as evidence. But it also was like, that has to take back seat, because our first responsibility is caring for those bullfrogs. And they're not in a position where they can lose anybody right now.

DN: Well, in Theory of Water, you talk about how overlapping worlds—like shorelines where land and water meet, or estuaries where fresh and saltwater meet—are places that teem with diversity, and also that they are places of regeneration. It reminds me of something that the poet Jorie Graham said about trees, that they are most present at the place they are most extended, at the tips of their branches, at the zone of encounter. We could contrast these overlapping zones to the 42 locks on the Trent–Severn system of waterways in Ontario, which end up devastating it by separating everything. I also think of Robert Macfarlane in his new book Is a River Alive, in a section called “Drowning a River.” He talks about how Quebec, since the 1880s, has been converted into a vast electrical machine—that Hydro-Québec is the world's fourth largest producer of hydropower in the world. The 2011 plan Nord to industrialize the Far North—one of the largest intact ecosystems in the world—where 14 of the 16 large rivers are already now dammed, and where labor camps that include gyms and supermarkets and more are set up deep within the boreal forest. I also think about your work across books and across many of your talks when I think of diversity, diversity of strategy, diversity of mode of being, perhaps like the different animals on the back of the turtle. For instance, in commemorating 22 years of the Grassy Narrows blockade, you say the blockade is modeled after the work of the beaver: “It is a refusal of everything that destroys life from pulp mill effluent and mercury contamination, to deforestation and mining, to climate catastrophe and nuclear waste dumping. And it is more than a refusal. For twenty-two years, the land and water protectors at Grassy Narrows have been showing the world that there are ways of living within the network of life that are based on deep reciprocity. Their perseverance, resistance and profound love for their land is a beacon of hope for me.” Similarly, in talking about your beaver-centric book A Short History of the Blockade, you talk about blockades as both a negation and an affirmation, and that, unlike the beaver in the colonial imaginary as a sort of industrious engineer, beavers are the practice of wisdom. You talk of their waterproof fur, webbed feet, third eyelid, how their deep pools and channels drought-proof the landscape, and also provide cooling stations. That they're a builder of shared worlds—worlds that bring water. That in pre-colonial North America, there were up to 400 million beavers. Beavers in every stream. Then I think of the raccoons in your book Noopiming, which you describe as the ultimate radicals: “Sure, they had been dispossessed, displaced, and their habitat gentrified like everyone else, but they were not taking it. No way. They moved the fuck back in, committed, built lodges, spoke their language, did their ceremonies and took care of each other. They had kids and more kids and raised them up to be self-determining fire. They figured out how to live with the asshat humans in harmony such that the biggest asshat human complaint was that they had to clean up their garbage every few days.” I'm not sure if this is what you mean by diversity—the beaver mode and the raccoon mode, or the debate in Noopiming between the resident and migratory geese—but talk to us about this aspect of Theory of Water. What diversity—such a word that’s been emptied of meaning in the common Western imaginary—this question of diversity, what diversity is and means for you in creating coalitions and resisting erasure?

LBS: I think that I’ve been taking an expansive approach to diversity. And I think with the Anishinaabe thought, diversity is seen as something that’s very necessary and very good, and that comes from nature, that comes from the land. You look at a forest, and it’s a fantastically diverse place made up of all kinds of different plants, trees, shrubs, insects, animals, birds, fish. It’s a cascading entity that’s a network made up of all of these different species that have figured out a way of working together to bring forth more life. I think there are limits to that. So I think in my work, I have sort of put this boundary, like, I’m going to refuse colonialism, I’m going to refuse racial capitalism, I’m going to refuse heteropatriarchy. Those are the refusals. And now I’m going to work within this—the rest of the world—to come up with something that’s different, that’s a radical imagining out of that. That’s a worlding that is collaborative, and therefore not just Anishinaabe-centric and not just Leanne-centric, but it’s a way of generating, I think, relationships that are modeled after this expansive network that is our planet. I think that that’s, for me, a generative space to exist in. In terms of solidarity, I think of that, I remember in Idle No More, we had lots of conversations about how to forge solidarity with Canadians and with non-Indigenous people that we needed as allies, and that we needed as support. And that shift now, for me, is, “Okay, I’m going to put that boundary up again where I’m refusing capitalism, I’m refusing heteropatriarchy, I’m refusing those worlds. And I want to invest in relationships with anti-colonial movements and with people who are also radically imagining their way out of fascism.” I think that creating constellations of co-resistance—constellations of mutual aid—that can be a place of learning and of fostering the skills that we need to rehearse these different forms of living and ways of life.

DN: Do you have any thoughts about holding a space for diversity of opinion within a functioning coalition? So you've already said the nos. Because I think of your people as joint stewards of the land with your neighbors, the Haudenosaunee. But also think about how, particularly online, it feels like there's this immense pressure exerted on language to get everyone to adopt the same analysis and the same vocabulary, or else you're like flipped out of or thrown out of the group. But I also think about this series of episodes on The Dig podcast about the history of Arab organizing, radicalism, and resistance. This I don't remember the guest name—an Arab scholar and historian—talking about these, what he considered huge strategic errors, where, say, one group is hardcore Marxist and the other group is Marxist light, and the differences seem absolute and vital and essential in the heat of the moment to the point where they don't join up, or they are having friction with each other in a way that sort of takes their eye off of who the real oppressive power is at a time when you can absolutely not afford to do so. I mean, partly I was also thinking about, I was listening to the head of Jewish Currents magazine, Arielle Angel, talking about how it's vital to be doing all of this organizing offline in shared activity. So I think back to you being away from the screen, but also think back to theory as something kinetic. I mean, maybe some of these things that are happening, mediated virtually in a disembodied space, become so polarizing and binary because they're happening in that context. But I wondered if you had any more thoughts about, in the moment, these differences seem huge. But then you look back on history, like on this podcast, and you're like, “Wow, these two people should be facing the same direction,” and then figure that difference out way farther down the line.

LBS: Yeah, that's a fabulous series that The Dig did with Abdel Razzaq Takriti the Arab scholar. I think, yes, I think I agree that we need to skill up in terms of relating to each other across our differences, particularly differences that are fairly minor. I think that that's what Robyn and I were trying to do in Rehearsals for Living, because there have been tensions between the Indigenous community and the Black community, in the academy, not so much in organizing, but we wanted to sort of take a very intentional approach to relating to each other, to sharing in a way that was respectful and that was mutually reciprocal, but that didn't shy away from some of the more difficult conversations as a practice and as a way of skilling up, having those conversations and respecting that our movements are different, but they are linked. So making space for difference and also finding ways of linking, I think, are important in broadening anti-colonial movements and developing the kinds of larger-scale solidarities that we need to face what we're facing right now. So I think that internally we have a lot of work to do in that regard, and I know that there's lots of organizers who are doing workshops and putting a lot of energy into figuring out how to work through conflict in a way that's generative and that strengthens movements and strengthens relationships rather than causes more harm.

DN: Thinking of your moment of insecurity that you ultimately reject in relation to Black feminism and what your own tradition offers in the section that you read for us, you expressed something similar in your essay about Indigenous solidarity with Palestine, an essay called A Blow to the Snake Here, where after two of your Palestinian hosts were describing their many-year battle for access to their village's spring, you say, "Listening to Ahed and Bassem, I caught myself feeling ashamed. Worried that at home, we had gotten so tied up in treaty promises, royal commissions, national inquiries, reconciliation that too many of us stopped fighting. Worried that too many of us now live comfortable middle class lives in cities or on the reserve and do little more than activism. Worried that somehow in our emphasis on post-secondary education we had confused credentialism with a liberatory project and now we have a lot of degrees and access to the middle class and little else. Worried that maybe Indigenous struggles had very little to offer Palestinians in terms of solidarity. Palestinian resistance has revealed the smoke and mirrors of reconciliation." But you then go on to roundly reject your shame and describe in a deep way the Indigenous resistance that is happening, but thinking about this question of diversity in the struggle and that the power of regeneration occurs alongside and/or because of the diversity in the overlapping areas of difference, I wonder about those of us from peoples who don't have the stories, histories, or praxis of right relation to the land that Indigenous people do, and perhaps also haven't developed the liberatory theory and praxis of the Black radical tradition, I'm thinking of Americans and Canadians who are immigrants and refugees, whether Latinx, Asian, Arab, Muslim, or Jewish, who, regardless of the reason for our arrival—whether simply seeking opportunity or fleeing war or violence—we are nonetheless slotted into a settler position that is both often anti-Black and doesn't acknowledge or engage with stolen land. It feels like there's something generous, even loving in your expressing your insecurity, as it feels to me like one thing it provides is an opportunity to wonder out loud how non-Indigenous, non-Black peoples can weave ourselves into a struggle in a way that isn't extractive. I think of your meditation on elite capture in Theory of Water, how non-Indigenous researchers and environmental activists see the inclusion of your work and other Indigenous peoples as making their work more ethical and robust, but how in the way it gets reduced and framed and captured in the process, it ultimately recasts the work in a counter-liberatory way. That regardless of intentions, the impression of collaboration is a means to disrupt real Indigenous resistance. This is sort of my long way of asking both about your thoughts about a diverse coalition of people who don't have the practices, don't have the stories wanting to take steps towards being woven in and what that might look like and what the distinction is in your own work that you say you've moved away from non-Indigenous allies and instead towards organizers, scholars, and thinkers engaged in the struggle for liberation.

LBS: I think I've moved away from trying to get white people to be allies to Indigenous movements, to asking myself, "How are you, Leanne? How are you in solidarity with Palestine and Palestinian people? How are you in solidarity with this global movement for Black Lives?" That has been very, very powerful? It links back, I think, to the section in the book where I'm talking about Madeline Whetung's work in Curve Lake. She's describing growing up with her grandfather, Clifford Whetung, in his garden, and this is coming from her PhD dissertation, she's talking about how we learn accountability at the shore, and it's not a big public shaming or an internet call-out. It's a practice of self-reflection, first and foremost, where you're constantly looking inside yourself and thinking, asking yourself these questions of accountability. It's not something that you're going to outsource to the people that you're in community with. You try to be responsible for the areas in your life that you don't know very much about, the things that you wish you didn't, the mistakes that you made. So one of the ways I think that I have been learning about solidarity and learning about how to foster relationships across difference is by thinking and acting with these other movements that have been doing such incredibly important work, even though there hasn't been maybe a large-scale Indigenous mobilization since Standing Rock. So, asking myself and asking the circles that I'm a part of, what are we doing to materially support the anti-colonial movements that right now are mobilized and need our help? So that shift was beautiful and really important, I think, for me.

DN: Well, earlier this year, I took an eight-week course with an Australian psychotherapist and organizer, Leah Avene, on collective recovery from what she calls colonial fragmentation disorder. Her family is from Tuvalu and from Ireland, from two Indigenous bloodlines, but even as she holds a research position as the Indigenous pedagogy lead at the Wilin Center for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development and works under the mentorship of Indigenous Australian teachers, she is a settler and presents herself as such. But what we worked through together as a group had to do with narrative recovery through practices of place, body, and story, and also shaping a field of being that moves from a disfigured relationship to the land to a dignified relationship with the land. Part of that was honoring one's own ancestors and bloodlines from elsewhere, but part of it was learning about and engaging with the stories and histories and peoples of the place where we are, wherever that is. Through this practice, I shamefully am just learning about how Portland wasn't a place before colonial settlement, where people lived as much as it was a place, a great wetland, where the Kalapuyan people came to forage and hunt, that it was a place abundant in beaver and duck, which now are mainly thought of as our two main football mascots rather than a creature you would come across moving through the world on a given day and how these wetlands were filled in with earth and rock and trash, and many of the streams and creeks and springs, which were all over Portland pre-Portland, were buried beneath the earth so that the city could be built without considering them. But thinking of these people gathering with Leah, mainly from different parts of Australia but also some people from India and from Canada and the US, it made me think of my conversation with Alexis Wright, the most celebrated Aboriginal writer, and how she described Aboriginal culture as cosmopolitan. She makes a distinction between cosmopolitan and assimilationist. To her, it meant a culture that was open and open to influence, but without losing one's own vantage point, which sort of feels a little bit like sintering. I think of how you speak in this book and other books about Indigenous internationalism, for instance, in Rehearsals of Living, you talk about a politic of sharing, a "continual divestment of individuality and a perpetual deepening of the communal, a politic that's anti-accumulation and intertwined with a politic of caring," and likewise in the same book how water insists on internationalism, on seeing ourselves outside of our own perspectives, which I really like. And one of the stories you tell related to this is about the history of the eel, which used to be extremely abundant in inland Canada. I was hoping, I mean, if you have any thoughts about anything I just shared, I'd love to hear them, but I'd also love to hear about the eel and about the eel in relationship to perhaps an idea of internationalism.

LBS: Yeah, so my homeland is roughly the North Shore of Ontario. So, Doug and I were out. I can't remember. I think we were hunting for geese in the fall in a canoe. He was talking about eels. He was remembering, I guess, the spot that we were in, he remembered being there as a kid, and the lake was teeming with eels. I was like, "What? What kind of eels? What's going on?" And he explained how, before the Trent-Severn Waterway and the lift locks, also on the Saint Lawrence River, that eels traveled in large numbers into our territory and into our lakes from the Sargasso Sea. And so that became an interesting thing for me to consider, because there are very, very few eels in my territory now. I had trouble finding even our word for eels. I had trouble finding eel stories because they've been so decimated. Yet, he had this thread of knowledge about it from his childhood. He would have been alive just at the very end of eels in our territory. That showed me this cycling and seasonality of Anishinaabe life, where different seasons, our nation was composed of different nations and different beings. There was a lot of movement. There was a lot of cycling. The eels would come in the spring with knowledge of what was happening in the Sargasso Sea based on how healthy they were. They would spend their time with us, and then they would make that connection and make that journey back. So I started to think about my homeland not as the way that I had been taught by a colonial society as this piece of land that we fight over with Shoshone in terms of where the boundaries are, where my nation is not a nation state, and it's a collection of very deep relationships that extend across great distances and time and space and connect to everything on the planet. That's a very, very different way of looking at a nation than this Westphalian nation state with borders that you defend. So the eel was really the species that I think I learned that from. I started to see, once I learned that kind of eel story and that history, I started to see Anishinaabe internationalism everywhere.

DN: Well, thinking about both how water violates home spaces, crosses borders, connects distant places, and how it overlaps producing more life and a diversity of life, I wanted to ask you about your writing in relation to your other forms of art making. For instance, how you see your book Theory of Water in relation to your album Theory of Ice, or the album Theory of Ice in relation to the Theory of Ice section in your novel, Noopiming, or how the song on Theory of Ice called "Failure of Melting" is also the name of a poem in Noopiming, whose narrator lies frozen in ice. I also think of when I think of different modes of representation, the tree in that book is itself reading the book The Hidden Life of Trees. But talk to us about the overlaps and cross-pollinations and divergences between how certain themes or questions find themselves in these different artistic containers.

LBS: Sometimes I think that I'm just writing Dancing on Our Turtle's Back over and over and over again, and it's just that like my knowledge is deepening, and I'm working with the same sorts of the same origin stories, the same teachings, the same land-based practices, but my knowledge is deepening and the world is changing, and so the books are changing. But I think ultimately, I love making music, I love writing fiction, I love writing nonfiction. And so whenever I get an idea, I work with it, I think, in different genres and across different disciplines as a way of deepening my understanding and teaching my own self. That kind of creates all of these crossovers between projects. I think Theory of Water was really born in that last letter to Robyn Maynard, where I start to think about the kinds of issues that Robyn and I have been discussing, but outside of the Black and Indigenous community now, like in a more expansive way. But then I also draw on the work that I was doing musically and in Theory of Ice. Music is interesting because lyrics are a kind of poetry that is in collaboration with the voices of different instruments and different musicians. But you often, when you put out a record, you generally go on tour and you do shows and there's a repetition, there's a rehearsal where you're saying these words and singing these songs over and over and over and over and over again to different audiences. In those rehearsals, I think I am also thinking of the ideas that I'm working with in the lyrics and in the songs, and so that becomes a generative spot for, like the five hundredth time I'm singing a certain song, I'm on this ski trail or I'm out for a run or I'm grooming the light bubble will go off and I'll make a connection that I haven't made before, and that will sort of work its way into the next book or record. I work on one thing at a time, but the hard work of the first draft, I will only be working on one thing for that, but then I will be mixing a record at the same time or editing fiction. So it's also kind of all crossed over that way. I think that I'm not trying to break open genres or disciplines. I'm just trying to do what I do, or maybe what I can do. It comes out in a way that doesn't fit into the containers of the Western world very well.

DN: Before we end, and perhaps as a way to bring things to an end, it feels important that we talk about maps, given the subtitle, Nishnaabe Maps to the Times Ahead, what maps are and are not in this way of being. Some mentions of maps of yours include, "The vision for the future is not a fixed map but a set of ethical practices," or how the creation stories "tell us there was no map, no research plan, no set of strategies. There was no land and no leader. Just love and hope and a fostering of emergence." You talk about the eel’s body as a map, much like a tree trunk is a map. But thinking of water again, one thing that stuck with me is you talk about how fresh water is less than 3% of the total water on the planet, but that only 0.3% of the 3% is lakes, rivers, and swamps, that almost all of it is either frozen in ice caps and glaciers or beneath the surface in groundwater. Thinking about all of this unseen water makes me think of your section in the book called Maps to Statelessness, a type of map that isn't of a fixed position in space, but a map of relationship and presence, and how you say if you were to make a map of your territory, it would be a song. So I was hoping you could talk about space and time in relation to maps, but also about two meditations on maps you make in the book. One is your video contribution to the 20th anniversary celebration of Dionne Brand's Map to the Door of No Return, which I will point supporters to because it's a really incredible video called Pinery Road and Concession 11, which feels very much about the impossibility of spatial navigation in a colonial setting. So I was hoping maybe you could talk about maps, and then about that video, and then maybe we could go out with a reading of the book about the map on the back of the turtle as a counterbalance.