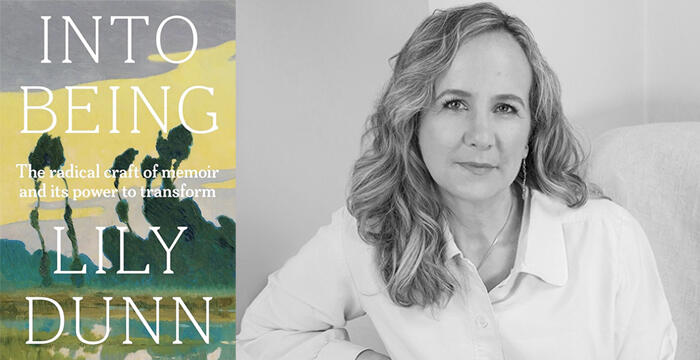

Lily Dunn : Into Being : The Radical Craft of Memoir and Its Power to Transform

In Into Being Lily Dunn explores the ways in which writing one’s life has the potential to transform it; how writing, if done well, can produce “symbolic repair.” We look at Virginia Woolf’s notion of “moments of being” as a means and method to find the form that best fits your specific story to tell. We look at different ways memoirists have used the imagination within their own work, and the various ethical issues that arise when writing about people close to you or about other peoples’ trauma. And from beginning to end, we look at Lily’s own remarkable memoir, Sins of My Father: A Daughter, A Cult, A Wild Unravelling, as a way into these questions as well.

For the bonus audio archive Lily walks us through one of the writing exercises in the book. This joins a large and ever-growing archive, everything from craft talks by Marlon James and Jeannie Vanasco, to writing prompts from Danez Smith & Lucy Ives, to readings by everyone from Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore to Richard Powers. You can find out about how to subscribe to the bonus audio and about all the other potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community at the show’s Patreon page.

Finally here is the BookShop for today.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today’s episode is brought to you by Brick, a literary journal. Each issue is as purposely crafted as a good novel, says John Irving. Juan Gabriel Vásquez calls Brick “an indispensable feature of my personal landscape and a place I visit to renew my pact with the written word.” Christina Sharpe declares Brick “a wonder.” An international literary magazine based in Toronto, Brick is beloved by writers and readers the world over. The masthead of each issue hosts these words from Rainer Maria Rilke, as translated by E. E. Cummings: “Works of art are of an infinite loneliness and with nothing to be so little reached as with criticism. Only love can grasp and hold and fairly judge them.” It’s this love that drives Brick to publish the most invigorating and challenging essays, interviews, translations, poems, and boundary-pushing fiction. Brick’s winter issue is available now, featuring Lydia Davis, Cristina Rivera Garza, Madeleine Thien, Solvej Balle, Rinaldo Walcott, Diana Seuss, and many more. Visit brickmag.com to subscribe to the magazine or gift a subscription this holiday season. Print subscribers get free access to Brick’s complete digital archive, with issues spanning nearly 50 years. As a bonus for Between the Covers podcast listeners, take $5 off any subscription with the coupon code BETWEENTHECOVERS. One thing that we explore in today’s conversation with Lily Dunn is how one’s story changes depending upon the frame within which one tells it. As you’ll see, there might be no one better than Lily to speak about this, who has done just this with fiction, nonfiction, documentary film, and now a craft book on the ways writing one’s life can lead to transformative change within. Speaking of change, not just the change of the calendar year, with this being the first episode of 2026, this podcast is about to go through a change, as this will likely be the last episode partnered with Tin House Books. I wanted to take a moment to reflect on this. Back in 2018, I had been doing this show for roughly eight years on a local community radio station, and I was approached by Tony Perez, who at the time was one of the senior fiction editors at Tin House, and also the person who acquired, edited, and shepherded my book with Ursula K. Le Guin, Ursula K. Le Guin: Conversations on Writing, into the world. He wanted to explore the possibility of having the show’s home at Tin House, of finding a symbiotic relationship between me and them. The last six years at Tin House have been just that. I wanted to first simply thank all the people there who were often doing extra work beyond their normal obligations to help make this partnership thrive as it has. Tony, for the vision and invitation. Lance Cleland, for support in innumerable ways, and also for creating and nurturing the most incredible writing workshop community. I felt like there were and are so many uncanny correspondences between our sensibilities with regards to the politics of curation and community building. Elizabeth DeMeo, Alyssa Ogie, and Becky Kraemer, who probably did the most for me week in and week out. Masie and Nancy, and many others who have made me feel part of a family, of the Tin House family. Thank you. I wouldn’t be where I am today without all of your care and kindness along the way. This has been a big year of change for Tin House. Ten months ago, Tin House Books was acquired by a larger independent publisher, Zando, and the Tin House workshops are rebranding as a separate organization, which you’ll surely be hearing about shortly and which I encourage you to follow. Next episode, I will share where Between the Covers is going and my excitement about this new era, but I wanted to devote the time today to simply say thank you to where I’ve been. While this big change on Tin House’s end and the big change for Between the Covers on the horizon aren’t unrelated, there’s nothing but good feelings between us all. Zando has been a great steward of the show during the past year, and I still love Tin House books and the people who bring them to us, writers from Morgan Parker and Tommy Pico to Morgan Talty and Raymond Antrobus, from Gabrielle Bates to Myriam Chancy to Elissa Washuta to Zahid Rafiq to Megan Fernandes. So a hearty thank you to Tin House Books and the Tin House Workshop for everything. Before we begin today’s conversation, the first of the year and the last of an era, a conversation with Lily Dunn about her book Into Being, I’ll mention that her contribution to the Bonus Audio Archive walks us through one of the writing exercises in the book. This joins craft talks from Marlon James and Jeannie Vanasco, writing prompts from Danez Smith and Lucy Ives, and much more. You can find out about how to subscribe to the Bonus Audio, and about the many other potential awards and benefits of joining the Between the Covers community, when you transform yourself from a listener to a listener-supporter at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today’s conversation with Lily Dunn.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning, and welcome to Between the Covers. I’m David Naimon, your host. Today’s guest, writer, editor, and teacher Lily Dunn, has an MA in creative writing from Sheffield Hallam University and a PhD in creative writing from Birkbeck, University of London. In her 20s, Dunn was an editor at Time Out, and later a columnist at You magazine. Her debut semi-autobiographical novel, Shadowing the Sun, came out in 2007\. Tim Guest says of it, “A funny, harrowing and ultimately heartbreaking glimpse into the tribes of a lost continent: the children of the Seventies ‘Me’ generation, with their inheritance of wild freedom and poisonous neglect. I both laughed and cried. Seen through the cut-glass mosaic of Lily’s sharp perceptive talent, the book becomes something new: not just a recollection but a gift, to the past and to us. Full of a hard won, lonely kind of gratitude.” In 2021, Dunn co-edited the anthology of recovery stories, A Wild and Precious Life, which emerged from her teaching creative writing to people recovering from addiction at the Hackney Recovery Service. The following year, she published her debut memoir, Sins of My Father: A Daughter, a Cult, a Wild Unraveling, which was picked by both The Guardian and The Spectator as a nonfiction book of the year. The Times says of this book, “This is a memoir of two lives: Dunn’s father, who took enthusiastically to the Rajneesh cult, and Dunn, whose life is overshadowed by this early abandonment. She writes with cold, controlled anger, but also empathy. It’s a gripping tale.” Zoe Gilbert says, “Lily Dunn manages the magic trick of rendering pain exquisite, and making beautiful the vacillation between heart and head, love and reason that characterises human relationships.” Amy Liptrot says, “I was obsessed with Sins of My Father, a memoir which combines the emotional and the cerebral in telling the story of a life through the prism of a father's influence. It is a victory of self-knowledge and compassion, as well as art.” Lily Dunn was also a consultant, producer, and writer for the documentary film Children of the Cult, nominated for a Bafta, a Best Documentary Edinburgh TV Award, and a Best Documentary by the Royal Television Society, a film directed by a childhood survivor of the Rajneesh Commune that interviews other former Commune children, revealing that no one has yet been called to account for the harm caused, and in the course of filming, unmasking and confronting perpetrators in real time today. So if this were not enough, Lily Dunn co-founded London Lit Lab, which offers online courses for writers of all levels, teaches advanced narrative nonfiction modules at Bath Spa University, and offers a monthly teaching session called Memoir Writing in Progress Surgery on her Substack. Lily joins us on Between the Covers to talk about her latest book, out this fall from Manchester University Press, called Into Being: The Radical Craft of Memoir and Its Power to Transform. Cristín Leach for the Irish public broadcaster RTE describes Into Being in their Book of the Week segment as follows: “The best memoirs tell a story that’s compelling not only in its circumstance but in the ways the author navigates the problems of a form Dunn describes as 'fascinating, sometimes hazardous'. Into Being addresses the very human fallibility of memory, ethics, permission, perceptions of truth, censorship (of self or otherwise), and what it means to publish memoir when we live now 'In an age of social media, filled with confessions, re-inventions and distortions of the self.'” Finally, Elissa Altman says, “Into being is a startlingly beautiful book that unpacks the craft of memoir with compassion and vast wisdom. Lily Dunn has written an indispensable companion for any writer embarking on the time-bending, often overwhelming journey that is the creation of memoir. I loved everything about it, and I'll be giving copies to all of my students.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Lily Dunn.

Lily Dunn: Thank you so much, David. It was lovely to listen to. Thank you.

DN: So you first reached out four years ago about the anthology, A Wild and Precious Life. We almost talked for your memoir, Sins of My Father. But I’m glad we waited, because I’m fascinated by how different frames change how we tell our stories, that you’ve now written about the same elements of your life in fiction, then in memoir, then with your participation in documentary film, and finally a craft book, all of which circle the same vital questions you have around your own life and family. Hopefully, today we will travel through these different frames and explore what they do and don’t do. But as a way to start, I wanted to start with a different frame, a different lens, a cultural or national one. Two things that struck me as possible cultural differences between the UK and the US that I’d love to spend a moment with. In your craft book and your interviews around it, you often refer to memoir as a niche genre. On Facebook, you call Into Being the only book of its kind in the UK. This leapt out to me because, in contrast, over here, Vivian Gornick’s remarkable The Situation and the Story, which you engage with and explore in this book, is from 2002\. Before that, in the 90s, was Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir. After these, there are many, from Natalie Goldberg’s Old Friend from Far Away to Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir to more recent notable editions, Melissa Febos’ Body Work and Elissa Altman’s Permission. In a similar vein, I don’t think most Americans would see memoir as niche, but rather alongside novels as the most sought-after and marketable of books if we look across genre. So this seems to point to something interesting I’d love to hear more about, your thoughts about this disjunction and how our two cultures, which share a language, have engaged with or not engaged with this form of writing.

LD: Yeah, really good place to start. Well, one of the reasons that I wrote Into Being was because I was studying memoir on my PhD. I wrote Sins of My Father on my PhD, and I was studying memoir for the critical component and really just trying to bridge the gap between what I defined as writing well and writing to get well, so bridging the gap between writing as art, I suppose, and a form of excellence, artistic excellence, and writing for therapeutic purposes or well-being. Obviously, I was looking at a lot of books on memoir and recognizing that most of them were American-published and written by American writers. I mean, for one, I looked around for UK-written books on memoir, of which I couldn’t find any. I’d be very interested to be corrected on that. I mean, there are life-writing books published in the UK, but life writing is broader. As you know, it encompasses biography and autobiography and letters and diaries and all sorts, but nothing specifically memoir. I reflected on this and realised that, I mean, I have always read memoir, but didn’t really read it in the early days knowing it was memoir, because I was reading it as novels, really. It may be that in the early days it wasn’t necessarily marketed specifically as memoir, because memoir is still identified, I think, over here, certainly very much as celebrity memoir or a misery memoir, you know, certain categories, whereas what we’re producing here—and we do produce a lot of memoir here—is quite an elastic form. You know, it may not be marketed as such. It might be nature writing or it might be reportage or it might be journalism. It is very much read in the UK and very much loved. I think it’s often a heart project for an editor in a publishing house. But it doesn’t seem to have really made its way into the mainstream understanding in the way that it has in the US. I was quite interested in this recently when the whole Salt Path scandal broke, which you’re probably aware of. I don’t know whether your listeners are so aware of it in the US.

DN: I’m aware of it mainly from following you. I don’t know that that story has really broken into the literary consciousness here, nor, say, the controversy around Julie Myerson, which I know was big in the UK. But when her book came out here with Tin House, I don’t think that controversy came with it in the same way. So if you want to speak to the Salt Path.

LD: Well, The Salt Path was a very, very popular book here and it was a bestseller, and it was a memoir that did very well, which is quite unusual. There are some breakout titles. We had H Is for Hawk with Helen Macdonald. That was a breakout title, a UK author, obviously educated, did very well as well. Tara Westover’s, but that’s an American author. But The Salt Path was very successful here, and it was basically about Raynor Winn and her husband who went on a long journey on the South West Coast Path from Devon to Cornwall. So the story was that they were scammed out of their home and they were victims of a debt that went wrong, that they had lost their home, they were middle-aged, and Moth, her husband, was very unwell with this terminal illness. They did this walk and it was a classic journey, and it became a miracle cure for his illness. The thing that was discovered, there was a big Observer article, a piece of investigative journalism, that discovered that Raynor Winn was actually not called Raynor Winn. She had a different name, but also that they hadn’t been swindled. I brought it up because it struck me when people were talking about it on social media that people didn’t actually realise that it was a memoir, that it was supposed to have a commitment to truth and honesty, because they’d read it like a novel and it was written very much like a novel. So coming back to your question about why the UK is possibly different or behind with their understanding of memoir, it comes back to what I was saying, that I think people don’t actually have very much of a grasp of what memoir is. It didn’t seem to matter to them what is the important contract that a writer of memoir has with their reader, which is honesty, in my view. In my view, you can use your imagination as much as you need to when you’re writing a memoir, because obviously, you’re dealing with the fallible nature of memory, you’re dealing with the unreliability of much of our past, which we can attempt to pin down as a type of truth. But our versions are very subjective, very different from other people’s. So you can use your imagination, but as long as you’re transparent about it. What I was struck with, with the readers of The Salt Path who were defending the story and saying it didn’t matter whether it was fiction or nonfiction, was that they hadn’t really grasped that fact about what memoir should be. I think that came from a lack of understanding of the fact that memoir actually is nonfiction, even though it sort of sits in that gray area.

DN: Well, let’s put a bookmark here, because I want to spend some time with the questions you just raised after we’ve introduced the book a little bit more and what your book is. But staying with this question of form and frame, several elements of your book leap out, perhaps more than any other, that it’s polyvocal, that because you’ve interviewed so many memoirists yourself, you bring a chorus of insight into process and theory and approach and ethics. So you might have a certain ethical or process approach, but then you will give other people’s that might be oblique or countervailing. So we get a lot of different experiences and sensibilities alongside your own. But you’ve also talked about your book in a more general sense as a hybrid book, a book that is both a craft book and also, in a way, a second memoir for you. Now, I wanted to hear about that. Can you speak to why this is a hybrid book in your mind?

LD: I think because writing to me is so bound up with my life. I suppose it relates also to your first observation about my books, the books that I’ve published, books I’ve written, and also the film I was involved with. So I didn’t want to write a manual on writing without bringing in examples of how I live and how writing is completely enmeshed with the way I live and the choices I make in my life. There is that element in Into Being of the transformative power of writing. I’ve always been aware of how writing has been transformative for me in that it’s been helpful to me on a very personal level. But I think what I wasn’t aware of until I wrote Into Being was how closely aligned the choices that I had made in my life to follow a particular path that was truthful for me was so intertwined with me finding a clarity in my voice and the clarity of vision in my own writing. It was really important to me that I wrote Into Being as a hybrid book in that I was showing how writing came out of situations. It came out of decisions, potentially transformative decisions that I had made.

DN: So some memoirists have come on the show and talked about using existing forms for their books, for instance, Courtney Maum using the classic three-act double timeline, and others like Elissa Washuta have talked about using less common hermit crab forms, adopting a shell for one’s story, in her case, everything from tarot to self-help books to Twin Peaks. You have a chapter in Into Being that looks at what you call protective forms like this. But at its core, your book suggests a different approach altogether, which I found very compelling. When in the preface you say that this is a craft book to a certain degree, but not in an obvious sense because it isn’t a how-to book, I suspect it’s because of this element that you suggest not thinking of form early on, that because writing memoir is so personal and our life stories are so idiosyncratic that one should allow the structure to find itself through the process of writing. This way forward, this method through which to discover one’s structure, feels like it involves some work and skill at sifting through one’s own life narrative. To guide us, you talk of Virginia Woolf writing about how so much of life is a series of moments of non-being. You suggest that by focusing on moments of being that return to you, that prick you, that have pierced the featureless everyday because they hold meaning, that this meaningful memory is the greatest antidote to the blank page. Of course, speak to any of this generally, but I’d also love to spend a moment with the journey of you finding the form for your memoir, Sins of My Father, so how you found the form not starting with the form, and also what your meaningful memory was, your moment of being that serves as the well from which to draw forth the book?

LD: Yeah, lovely question. So I think memoir is highly, I mean, we know it’s highly subjective, but it evolves out of a very particular life, doesn’t it? So one of the things I argue is that you couldn’t teach genre memoir, for instance, in a university module, because how could you create something homogenized from something that’s so immensely diverse in the way that different people will approach finding a story within their own lives, their own experiences. So I do tend to encourage my students not to try and pin down a structure, at least until they’ve written a first draft, because I think the writing finds the story, and I think it’s Vivian Gornick who writes about this in The Situation and the Story, brilliant book, where she talks about the difference between writing a scene or a situation or, you know, it could even be an anecdote. You know, this happened, it’s a plot point. Finding the story, which is about finding the meaning from that event, is what does that event illuminate? How do we reflect on it? What do we find out about it? And really, the story is embodied in that meaning-making. So a way into writing memoir, I mean, obviously, is recalling memory. But more interestingly, I think it’s this concept of moments of being, which, as you mentioned, comes from Virginia Woolf’s ideas of the cotton wool of moments of non-being that surround us in our everyday lives of getting up and doing the hoovering and having breakfast and things that we just don’t remember because they’re everyday things. Then we’ll have what she calls a violent shock of something that will happen that will embed itself in our consciousness. The way she describes it is it’s there in order to be better understood. So it might come back to us and haunt us through our lives. I think all of us have these moments. Whether we’re aware of them or not is what makes us an artist or not. You know, if you start to engage with the resonances, the things that bubble up in your consciousness or just come and visit you in your dreams even, then you start to create something. You know, you start to dig into them and that’s when you start to find story. In Virginia Woolf’s case, she writes beautifully about this moment when she was in St. Ives as a child, which was her childhood summer home. A lot of her early memories involve her mother, who died when she was 13\. There’s this beautiful memory of her just simply lying in a room and listening to the waves and the blind is moving with the wind, and she writes about the little acorn on the end of the cord of the blind and how it drags across the floor. So it’s this very simple memory. But what it is that she remembers and the reason she remembers it is it’s the feeling that comes with it, which she calls a type of ecstasy. So I was reading this and thinking, wow, that’s just so beautiful. She calls it a foundational memory. I mean, this was me reflecting on my process of writing Sins of My Father. I suppose it helped me identify some of those early inspiration points for my own writing. One memory that followed me around for years and years was the memory of my father returning. So my father left the family home when I was six and my brother was eight, and he disappeared. So he didn’t tell us that he was going and he didn’t tell us where he was going, and what I realized later was that he had met a stripper in a club in Soho and she had introduced him to her guru, who was Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, otherwise known as Osho. This was in 1979\. It was the beginning of what became this big spiritual movement, which started in Pune in India and then moved on, when it got so big, it moved to Oregon, to a big ranch that they called Rajneeshpuram. Anyway, my father left in 1979\. He got up, packed his bags, and disappeared. He didn’t tell us he was going, he didn’t tell us when he was coming home, and he was gone for six months. I just thought he had died. You know, he was there and then he was gone. But the memory that followed me, that I kind of recalled and told to many people that I met through my life, was when he returned, the first time that me and my brother saw him when he had returned, and we were standing on the curb in Hampstead High Street in London, he was dressed in the colours of the sunrise. He had a mala, a beaded mala, around his neck with a portrait of his guru at its centre, and he was bearded. He was very thin because he’d had dysentery. He looked really different, and he had this slightly distant, dreamy look in his eyes. Me and my brother stood with him and he said that he had been reborn and that he was no longer our father. I mean, obviously, this was an incredibly important moment in my life because in many ways you could say it was an inciting incident, because it was the point when what had come before was no longer. Everything was different. The world that we knew was upturned, and also the relationship we had with our father was upturned. But what I realized as I returned to this moment was that there was something else in that moment which was deeper than that. It was that I looked to my brother and we both exchanged expressions with each other. In my mind, we smiled at each other. It’s almost as if we knew in that moment, even though I was six and he was eight, that our father had been swindled, that he had been caught up in something that was out of his control. Because it was something that was to return to me, this feeling, again and again, that actually, yes, I had lost my father, but it wasn’t necessarily his own volition. You know, he had been taken up by, he had been indoctrinated, basically. So I suppose I could say with more understanding now that that was a moment of being because it taught me something greater than the moment itself. I think this is what we’re looking for as memoirists, is we’re looking for those moments that are full and potent. You know, they’re full of story. They’re full of potential for something greater.

DN: Well, I want to stay with the question of form and frame a little more. For one, I think of the difference between the Netflix series Wild Wild Country and the documentary you helped develop, Children of the Cult. For people who don’t know much about Rajneesh, now Osho, and the giant community on rural land that he set up in Oregon in the 80s, his followers come from all over to build this place, donating their know-how and their labor. It even had its own airport. They take over this tiny town, Antelope, change the name of the town, change the name of the streets, transform local politics, become the police force there in these pink-red cop uniforms. Wild Wild Country holds a space formally to explore both the people who built the commune and the residents who preceded them and endured their arrival. We hear from people today who are part of the compound, who have great regrets and shame, and others who are still grieving the loss of what was the greatest time of their lives. Likewise, we hear from Antelope residents whose town is suddenly unrecognizable to them. If my friends are any indicator, they did a great job with this double framing. A close friend of mine grew up in a hippie environment and is married to someone from a Mormon background. It was like they watched two different movies, where one was swept up by the collective aspirations that initially motivated this new city out of nowhere, and the other was deeply sympathetic to the Antelope residents who were looked down upon and swept aside with scorn. On the other hand, Children of the Cult arose at least partially from Wild Wild Country, not dealing with what happened to the children in this commune or its associated communes in the UK and India. That isn’t to say that Wild Wild Country looked away or avoided the horrors of the commune at large. It explores their eventual stockpiling of arms, about trying to sway county elections with the largest bioterrorism attack in the United States, and by busing homeless people from around the country to their land to boost their voting population, ultimately unable to handle the mental illness they were encountering because of this and solving it by giving them all free beer laced with the antipsychotic tranquilizer Haldol. But because Children of the Cult is conceived and directed by survivors, everything about the experience of watching this film is different. It isn’t holding two points of view, obviously, but deeply investigating from and on behalf of those who’ve been irrevocably harmed. Because of this, I think it engages in less spectacle and is less interested in being entertainment. But this is my long preface to wanting to ask you again about your memoir and its framing, because several of the choices you make, which I think make it more powerful, also make it very powerfully uncomfortable, at least as I read it. I think the discomfort is part of its power. For one, like the Netflix series, I think you, to its credit, I think Sins of My Father takes seriously and holds space for the charisma of the Bhagwan. Likewise, and much more so, you do this with your father, which is particularly interesting because your father is this romantic figure for you. You’re under the sway of his charms far more than your brother. You could look at some of the choices you make in the book as perhaps influenced by this, mainly that upfront, we are given his backstory. We get a narrative for why he is the way he is. One small example: we learn that when he was young, he sexually abused his sister, but later confesses to her that he was brutally raped when his parents sent him away to boarding school at age seven, the same age you were, you note, when he abandons you and your family. It’s almost that you, I think, replicate formally the centering of your father in the book, but on behalf of a process that’s ultimately about separating and individuating from your father. I think it even asks us, or makes us complicit in a way, positioning us to grant more empathy to him than anyone else does but you. It also feels like the very thing that makes this reading experience very powerful as we follow you. Many people are taking exit ramps in his life, but you aren’t taking the exit ramp for a long time when everyone else in the book has. It’s the opposite of how most memoirs are written in this regard, I think, which would center your narrative and backstory. I understand that you might also call this a biography, perhaps, but a biography of your father who you are enmeshed with, so it’s inevitably a memoir. I wonder if this comes from the process of beginning with an impossible-to-articulate moment, like the one you just said. You have a father. He abandons his family. He comes back. He says he’s not your father. Maybe the allure, even with your skepticism and that knowing look with your brother, of “how do I get my father back?” or “can I find my way back to him?” And I would love to hear more about this aspect of Sins of My Father, which feels like a brave bravado, but also very disquieting move, essentially.

LD: It’s fascinating to hear you describe it like that. Yeah, I mean, that’s not in any way a conscious thing at all. I think that that probably taps back into this whole premise for Into Being of not having a form, not having a plan, really. I know that a lot of memoirs can be written with a plan, and in fact I’ve had discussions with other memoirists about this who have found it easier to give themselves a structure and to work within that structure, but I certainly couldn’t do that with my memoir about my father. But it’s really interesting that you pick up on that centralizing of him. I mean, obviously it’s a memoir about him and it is in some ways a biography, but this idea of the compassion, of the need to give him as much attention as I did in order to somehow find my own autonomy, and I don’t think that was a conscious move, but I think it felt a really necessary thing for me to do. I’m really interested in what you say about that being an effect on you as a reader, that you also felt that understanding or verging on compassion. I know not all readers have felt that. I think some readers have felt frustrated with how much I seemingly forgave him, although I don’t actually forgive him in the end. But giving so much attention to a character is a form of forgiveness. It’s a form of love, isn’t it? It felt incredibly important to me to try to understand him as best as I could. I mean, he was dead by the time I wrote the memoir. I found that through the process of writing about him, researching, talking to his sister, talking to my mother, he had burned so many bridges. There were so few people I could talk to, but I really needed to mine the ways that I could mine, you know, whether it was reading and researching, watching documentaries, watching YouTube documentaries about the Sannyasin movement. I had to try and understand how my father could have obliterated himself to the point that he did. Because he ends up having lived a very impulsive, very nourishing, very rich, successful life, you know, which was also spiritually aware and a lot of attention on himself and his development. He ended up squandering it all and losing everything to alcoholism and being deported from the US. He died on his own on the floor of a B&B in Ilfracombe in Devon, having been deported back to the UK. I had to try and understand how he had done that. By trying to understand how he’d done it, I had to understand him. I think, well, I know that I understood him so much better through the process of writing that book than I ever could have understood him when he was alive. That process of doing everything in my power to sit with him for the duration of writing that book, which probably took me about four years, I was able to speak for myself, which I’d never been able to do before because I was so subsumed by him and his influence. I was able to find a clarity of voice. I was able to actually evolve beyond and above him, almost. You know, it was like I was able to transcend his influence to the point that I could actually put it all to rest. So although it wasn’t conscious that I was doing that and that I was centering him to such a degree, I think it was a really necessary thing in my own healing journey, which also brought me to writing Into Being, because that really is what that book is about, that there is a therapeutic—if you don’t intend to write for therapy, actually—there is a very strong therapeutic outcome to crafting a very beautiful piece of work that comes from your life.

DN: Well, just as a point of clarification about my experience as a reader, I did find you frustrating. [laughter] But I thought that was all to the credit of the book. I believe you in the book and now that you needed to do this counterintuitive move of maybe even accentuating the problem of him being so central to your own life in the form of the book in order to find your way through and out. But during it, the experience, I’m like, “Come on. He doesn’t deserve the grace of this backstory.” I’m like, “Come on, Lily. Get off. Take an exit on this one. He doesn’t deserve your help right now. Center what the impact is on you.” Because for so long you’re not. I actually find that extremely, from an artistic perspective, extremely fascinating. Maybe it’s, I mean, also probably more honest to the actual lived experience. But this move of recreating your father’s spell, gracing him with backstory that makes us care about him before anything else, to always know that he was wounded, he was harmed, rather than centering the way you were wounded, but then slowly unspiraling it. I wonder if this separation, this carving out of your own voice as you described it, your own life on its own terms and finding autonomy, if this relates in any way to how you see the writer’s journey when you say, “the journey to give concrete form to a memory that is otherwise ephemeral allows the story to begin its evolution and its separation from the creator.” I want to hear more about what you mean by fostering a separation between the story and its creator and why it’s important that a separation happen between the story and its creator.

LD: I mean, I can’t say that it’s important because I can’t speak for anyone other than myself. But this question was certainly something I was exploring when I was writing Into Being. It was a question I asked because I interviewed various other writers who had written and published memoir around the time that mine was published. It was one of the questions I asked them. Actually, Noreen Masud was really interesting about this as well. She wrote A Flat Place, which is an excellent memoir. She talked about how writing A Flat Place helped her to give paper form to something that she’d been carrying around in a very sort of unformed way. I think she even says something like “with a voice that only she could hear.” To give paper form, I call it concrete form, to create something that you have control over, that you can make beautiful, that you can, I mean, it’s a transmutation in a sense, isn’t it, that you’re creating something new from an experience that you’ve been living and breathing and perhaps haven’t been wholly aware of for much of your life. That in itself can be an incredibly powerful thing because once you have created this concrete thing, this book, if you want to call it that, you can literally pick it up and put it on a shelf and be done with it. You can pass it on to other people and expect them to take what they will from it and it exists in its own way. So I believe in my own experience that that can be incredibly helpful for having distance from something that perhaps you’ve not had distance from and has actually dictated the way that you’ve behaved, you know, that it’s had such a powerful effect on you, which a lot of us do carry around these experiences that have not necessarily been positive, that we perhaps have felt victim to. That was certainly my experience. Some people could contradict that and say that actually maybe they don’t want to put away that stuff. You know, maybe they want to still carry the memory of somebody inside them and still be affected by it. I didn’t want to with my father. I really didn’t. I mean, he was so present in my consciousness and also in my writing life that, you know, I was writing a lot of fiction before I wrote, because I wrote three—I wrote my novel, my first novel was published, and then I wrote two other novels that didn’t manage to get published. But they were all following quite a similar character who was my father. [laughs] It was like he kept on popping up in all this stuff I was writing. Then it was only really by writing Sins of My Father, which is a much more direct form in nonfiction. It’s much more investigative. It’s much more research-heavy. It’s much more honest. It’s much more true. I wasn’t hiding behind anything. I was wholly myself, in as much as you can be when you’re writing as a character. It was only writing that that helped me put that ghost to rest. It was only by writing that that I could then turn my back on that part of my past. I was very happy to. I was very grateful to be able to do that.

DN: Well, I want to play a couple of questions for you from others that are both about reactions to writing one’s life. The first is a question about navigating the portrayal of others. Many of the closest people in your life are in your memoir, not just your dad, but your husband at the time, your brother. I would just say this as an aside about your mom, because she isn’t central in any way to the book, but I would call her the hero of your memoir, maybe inadvertently, the way she holds a space for you to have a relationship with your dad, despite how he treated her, to allow you to come to know him and come back to her over many years. I can’t imagine the strength that it took, and it was very palpable somehow in the book as an atmosphere the whole time. But our first question is from the author of multiple acclaimed memoirs, Elissa Altman. Her book Poor Man’s Feast was called by The New York Times “the finest food memoir of recent years.” It was followed by TREYF: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw, and then Motherland: A Memoir of Love, Loathing, and Longing. Most recently, like you, she’s published a craft book called Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create. Anne Lamott says of this book, “Elissa Altman’s marvelous, passionate and charming new book, Permission, is going to breathe freedom into your life. It is a clarion call for writers to tell their hard, lifelong truth, no matter how many decades they have agreed to stay silent. Lies and cover-ups won’t save you. This book just might.” So here’s a question from Elissa.

Elissa Altman: Hi, Lily. When writing about another person’s trauma, how do you navigate the ethical or moral line, especially if it directly impacts the life of the narrator? At what point do you make the decision to step back from telling a story that you feel you must, even if that story is about an event that also directly touched you?”

LD: Wow. [laughs] That’s a good question. It’s such a difficult question, but a fascinating question. I really love this question, Elissa, because it’s coming at it from an angle that is unusual, in that what normally comes up in creative writing memoir courses that I teach is this whole question of, well, because most people write memoirs about themselves, and obviously, other people come into that, and there is that blurring of how your story affects other people who are in your life and who you love, but actually writing about someone else’s trauma in your own memoir is a particularly contentious, problematic thing, which is something I inevitably had to think a lot about in writing about my father and also calling my memoir about my father Sins of My Father, which was a very powerful choice of title that I felt quite uncomfortable about, I must say, for quite a long time. There is no excuse in that he was dead when I wrote it. I think that isn’t an excuse, because in some ways it’s morally more problematic because he wasn’t there to defend himself. But I think what I felt I was comfortable with in the end, because I had to give this a lot of thought, was that I had been so affected by the choices that he made, and his choices had been so self-centered, and he was not a good father to me in any shape or form. He was not capable of being a good father. And I loved him so deeply, and that continued right up to his death. And I was actually willing to give up my life in order to try and save him, which my brother thankfully talked me out of. That actually writing about his trauma, I felt justified to do that. It felt like a really necessary liberation for me. It was almost like I had to place myself inside him to try and understand him to the degree that I could free myself from him. And I couldn’t have done that with any other character in my life. It was specific to my relationship with him. So if I was faced with writing a memoir about my mother, for instance, who had, as you say, David, was the hero in many ways in my book, even though she was a side character in many ways, although she was present throughout, I would have been far more careful and respectful. Yeah, I mean, I just wouldn’t have done that because of my relationship with her, because she always put me first, and it would have felt like absolutely the wrong thing for me to do, to jeopardize her or compromise her in any way through my writing about her. Even if she had given me permission to write about something traumatic in her life, I think I would have felt very uncomfortable about that, because I think there are questions around consent, which are complicated with loved ones. So yes, a really interesting question, which I’ll need to ponder on some more, I think.

DN: Just to circle back to the polyvocal nature of the book, one of the places that shines is we get to hear other people thinking through the same question that you just thought through for us, with different answers. So the second question, which is about a different form of engagement with the other, is from the writer Joanna Pocock. Her book Surrender blended memoir with reportage, criticism, and nature writing. Similarly, her latest book, Greyhound, pushes the boundaries of form also. Here is Lee Langley from The Spectator describing it: “Greyhound is a road trip like no other, a personal memoir interwoven with history, anthropology, and landscape. Despite the apocalyptic, Greyhound is not a miserablist read. Pocock’s rage is infectious and energizing, her prose vivid. In unexpected places, she finds kindness and generosity. There’s both darkness and brilliance here. Affection and laughter brighten the pages of this fierce, accusatory, tender, and unforgettable book.” So here’s the question for you from Joanna.

Joanna Pocock: Hi, this is Joanna Pocock with a question for Lily. My question is, what has been the most surprising response to your writing or to one of your books, a response that has made you see your work differently or frame it in a different light?”

LD: Gosh, yeah. Another amazing question from another amazing writer. Thank you, Joanna. Actually, it’s funny that you ask that question, Joanna, because you made a really lovely comment to me when we did an event together recently. You said that you were really struck by Into Being being a very generous book. I really stopped and listened to that. I don’t think that anyone had said that to me before, although I’m sure it probably has been a comment that’s come my way. I mean, generosity is something that I do—quite a lot of people comment on my generous spirit. I think I have quite a generous spirit as a person. When you said that to me, the fact that I might translate that generous spirit into my writing was a surprise. It was a really lovely surprise. It also made me reflect then on the anthology that I edited with Zoe Gilbert, which is A Wild and Precious Life, which I would say is a very generous-spirited book because it’s an embracing of all these recovery stories from multiple writers and emerging writers and people who, in a formal sense, weren’t really writers, but they were people who wrote for survival, you know, and that the whole movement behind that book was to give a platform to people whose stories and voices had been sort of silenced through their addiction or their mental illness. I think that comment that you made, Joanna, it just really helped me see that actually this generosity of spirit and communal approach to writing is a really important thing to me. I’ve taken that into another proposal that I’ve currently got out with editors and publishers. I think it’s, yeah, it’s something that I’d like to harness and think more about. So yeah, thank you. Thank you for that comment.

DN: Well, I want to spend a good amount of time on how you position writing memoir in relationship to therapy, because I feel like this issue around the therapeutic aspects of writing one’s life story is both complex and fraught, perhaps exemplified by, on the one hand, T. Kira Madden’s essay “Against Catharsis: Writing Is Not Therapy,” and on the other hand, Melissa Febos’ essay “In Defense of Navel Gazing.” I also want to stay with this through several questions that I’m going to pose, because I have myself complex, contradictory thoughts about it too. But I did want to start in the first question with a possible contradiction I see in your book. In your preface, you say that Into Being is not a book about writing for well-being. You say that if there is a therapeutic outcome, it happens accidentally. But I would argue that other than those brief passages, in the lion’s share of the book, you do speak of a non-accidental therapeutic aspect of writing. Here are just a couple of examples out of many. You talk about how you’ve always leaned on writing, as you also have today, to help you through major transformative decisions. That, “I am particularly interested in the dance between writing and gaining self-understanding in life and how intimately connected they are.” And "If I could bring life to difficult experience, find meaning in pain, make it beautiful by turning it into story, and if it wasn’t working, I could simply start again, I learned early that doing this made life more bearable." In talking about psychoanalysis, you say, "The memoirist is both the analyst and the person being analyzed." There are countless other examples in the book that twin what you find compelling about memoir to what it can do for one’s relationship to one’s own life. But before you answer this, I’m going to put some skin in the game and talk about one of my meaningful moments of being and how I see it in relationship to my own writing. You talk about writing down key moments in one’s life, noticing which ones quicken the pulse when you remember them. You say they might be the most difficult to articulate, but nevertheless, that these memories are a good place to start, which I really love, that this place where there’s almost like an unavailability of language is maybe the place that writing should begin. When you write this, of course, I think of your dad abandoning your family, coming back half a year later from India and saying he’s not your dad. Different clothes, different beliefs. The mystery of that gap and the enticement of the possibility of a return to a relationship, maybe even experiencing a renewal like he did. So one of my moments of being is my wife Lucy and I were in Varanasi, India, on the third day of a trip in 2010\. We were at a Hindu ceremony with thousands of people that was bombed. One moment I was among throngs and throngs of people. The next, I’m waking up having been blown to a different position, standing up alone in rubble looking for my wife, who looked asleep, curled up either unconscious or dead among concrete blocks. I still to this day don’t know how long I was unconscious or why we were there alone or what happened to the thousands of other people. I read about the stampede, the people who died, but I didn’t experience any of it. It’s a gap that’s filled with surrogate memories. But my way of contending with an irresolvable mystery and trauma, a rupture in the narrative of my life like yours, was to write. For the longest time, I wrote into this gap or I circled this gap in my writing explicitly. But even now, with many years behind me where I don’t write about this event at all, it still shows up in significant ways. For instance, Lucy and I both have new eardrums constructed by cartilage grafts taken from our outer ears. Last year I was invited to write for an anthology called Creature Needs: Writers Respond to the Science of Animal Conservation, where every writer is given a research abstract to create art in relationship to. So something very far from a bombing in India. But mine was a study about whether we could reintroduce two endangered species into the same lake, the green cutthroat trout and the boreal toad. But it ended up becoming about cross-species listening and the differences anatomically in how fish hear, amphibians hear, and how we hear. Similarly, the bomber who claimed responsibility was a young Pakistani doctor whose email to the press had the subject line, “Let’s feel the pain together,” which feels strangely like one way I think of as a frame for this show. But all this to say, I can’t imagine navigating my trauma without writing, so I’m not against a therapeutic frame around memoir writing, but I feel a gap or a tension or a contradiction between your book as a whole and those early lines that seem to contradict the book it is introducing. I guess I would love to hear, or I would love to spend a little time in that gap together and unpack that tension, if there is one, between writing a book about memoir writing, whose very subtitle talks about its power to transform, and yet cautioning us that this book isn’t about writing for well-being.

LD: Well, thank you. Thank you, David, for sharing that memory and that experience, which is extraordinary and defining. I mean, I can see that that is something that has had a physical effect on you as well as an emotional. I mean, that’s a hugely traumatic thing to have gone through. It’s incredible. Yeah, I mean, it comes back to what I was saying on the doctorate that I was doing. The PhD was really about trying to bridge the gap between how we perceive writing for well-being, writing for therapeutic purposes as a form of therapy, compared to this concept of writing well, which is crafting a piece of work toward publication. I think it is worth noting that if you venture into a project, you know, like you want to write a book or an essay, and you’re a published writer, you’re not doing it for therapeutic purposes. I was avoiding writing. It was my supervisor on my PhD who suggested that I write a nonfiction account of my father’s life, and my first response was like, “No way. Why would I want to do that? I keep on returning to him in my fiction. Why do I want to keep on returning to him and spend the next three years writing a nonfiction account of that?” I didn’t want to do it. I didn’t want to dig up a whole load of stuff. I didn’t want to put myself through it. So I wasn’t looking for that outcome. So I think it’s worth differentiating the difference because writing for well-being, if you go into a creative writing class that is solely for that purpose and you’re doing it to somehow exorcise an experience, the instructors will be very much leaning toward not wanting you to be self-conscious to the point of wanting a readership. You know, you’re doing that solely for your own purpose. That’s very different from crafting a piece of work. Into Being is very much directed at the crafting. But my argument is that actually it’s not so much that initial splurging. It’s not so much that initial raw experience that we all put into our journals. That, in my own experience, it’s not just that that is helpful therapeutically. Actually crafting, researching, living with, seeing things from different perspectives, embodying other characters, all of that can really change one’s perception, change one’s relationship with that initial experience. Having said that, I absolutely, wholly agree that writing well for me on a personal level has always been a type of self-therapy that I’ve done privately, and, you know, from a very young age, I learned how to therapize myself and make myself feel better when I was feeling—and I still do it—if I’m feeling caught up in something complex and I’m upset about something, if I sit down and write it out, I have the ability then to see it differently. It helps me. That process of putting it out on the page is a kind of dumping, isn’t it?

DN: I found even more compelling, not just that putting it down on the page, but you quote someone else calling it symbolic repair, which I think is less about putting it on the page and more about how you have some sort of autonomy over how you shape it once it’s on the page.

LD: This is the argument of the book, that it’s not just that initial splurge. I think the initial splurge is important, for sure. But actually, yeah, finding symbol, crafting, making beautiful. I mean, I remember also this ties into Elissa Altman’s question about ethics. My mother, when Sins of My Father was published, I remember her saying to me that she would have found it a lot more difficult if it hadn’t been so well written. I thought that was really interesting. I think it’s Phillip Lopate, or it’s one of those writers, who says that beautiful prose begs forgiveness. I really believe that you’re creating something new out of something that is embodied. That can only be—I mean, it’s the same when writing fiction or poetry—it can only be a restorative process. I think the initial splurging can actually be traumatizing often in some cases. But you get beyond that when you craft something. You’re detaching yourself from it. That in itself can have a therapeutic outcome.

DN: Well, we have a question for you from one of our foremost thinkers about memoir writing, Melissa Febos. Her memoirs include Whip Smart: The True Story of a Secret Life, Abandon Me, for which Febos appeared on this podcast in a really incredible interview, her craft book Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative, and most recently, Dry Season: A Memoir of Pleasure in a Year Without Sex. I wanted to share an exchange between her and Lilly Dancyger that relates to my last question and perhaps can serve as a preface to hers. Lilly first quotes Melissa from her essay “In Defense of Navel Gazing,” the lines, “I am done agreeing when my peers spit on the idea of writing as transformation, as catharsis, as—dare I say it—therapy.” Then Lilly says, “This idea really struck me. I’ve so often found myself getting defensive when people assume that my writing must have been cathartic. I want to push back and say, ‘No, it’s art.’ But you make such a good case in this essay for why it can be both.” Melissa says, “When my first book came out, there was a total onslaught of people being like, ‘Oh, so cool that you published your diary,’ when I had worked really, really hard to make that work of art. And I did the reactive thing, which was to be like, ‘It wasn’t therapy, it wasn’t cathartic, it was an intellectual work,’ thereby reinforcing what I see as a sexist binary between emotional and intellectual work. But those things weren’t mutually exclusive, and I never felt great about agreeing that they were, especially as I kept writing personally, because it was so obviously cathartic for me. It was so clearly saving my life.” So here’s a question for you from Melissa.

Melissa Febos: Hi, David and Lily. It’s Melissa Febos. First of all, congratulations again on your beautiful, thoughtful book, Lily. So many people are going to appreciate it. When I published Body Work, it was a little shocking to me how hungry people were for craft writing on personal nonfiction. I know they’re going to be so grateful and lucky to have this book in their arsenals. I also can’t wait to be a fly on the wall of this conversation between you two. I’m honored to interrupt it momentarily with an inquiry of my own. So here’s my question. It comes out of my own experience of writing memoir, but also of writing a nonfiction craft book. Did this book exercise something from you the way your memoir did? I mean, in the book, you beautifully quote Woolf describing how To the Lighthouse came to her like blowing bubbles out of a pipe, one idea bursting from the other, and how after the novel was done, Woolf’s mother ceased to haunt her. I’ve had this experience after writing memoir and essays. I know you have to some extent too. We’ve talked about it. But personally, I did not expect writing a craft book to free me from an obsession or set of obsessions. But ultimately, I found that it did. I’m wondering if you’ve experienced that also.

LD: Wow, I love that question. Thank you, Melissa. So lovely to hear from you. I value our conversation so much. It’s just been wonderful to meet you and talk to you about craft. Thank you. What a lovely question. Yes, I love that quote from Virginia Woolf, and I use that in relation to the experience of writing Sins of My Father. As you say, it really was like that for me. It was a laying to rest. Into Being is a funny one because, and I keep on saying this to myself even, I don’t even know where the title came from, and it’s such a perfect title for the book, and it feels like it kind of emerged out of nowhere. Of course, it didn’t emerge out of nowhere, because it has emerged out of ten years of me teaching memoir. But in a sense, it has emerged out of nowhere, because it is what I live and breathe and do. The book was commissioned, and I wrote it quite quickly. I’ve never written a book so quickly in my life, so it came as quite a surprise to me. So in a way, yes, I think you’re right. I didn’t expect it. I didn’t expect a craft book that has evolved out of my teaching to be a transformative book in itself, but because of the nature of how it has emerged and also the responses I’m now getting from my readers, it is also holding that power that Sins of My Father certainly held, and is becoming a transformative book in itself. And the thing that’s coming to mind at the moment is one of the events that I did here actually at my local bookshop in Bristol. I had a brilliant audience. I mean, I had so many people attend. I’ve never done an event with so many people, so many engaged people. When I was signing books afterwards, I had someone come up to me with tears in his eyes because I had said something that resonated so much for him, which was about giving him permission to write his journals, which he had been doing for much of his life. He was particularly upset and emotional about it because his father was dying of dementia. He had realized that by writing his journals, he had been collecting memories that his father was now losing. There was something so profound in this. I realized just sitting there that actually I’m speaking, it’s almost like I’m speaking to more people than I spoke to with Sins of My Father, because of course I’m talking to people who write as a practice in their journals, and it really matters to them. It’s making concrete their memories, their lives, these experiences that are otherwise lost. Yeah, so in answer to your question, Melissa, I’m very much still at the beginning of this process of talking to my readership, but it’s certainly proving to be quite a transformative book. Yeah, thank you.

DN: Well, there are some things in Sins of My Father and the documentary Children of the Cult that I think beg for a psychoanalytic frame. For instance, that your dad wrote a book about enlightened parenting called Wonder Child, or that at Medina, the UK branch of the commune, it was the children who cleaned and cooked, and the adults walked around in pajamas, fondling teddy bears and speaking baby talk. It feels like Freud would just be speechless seeing these moments. But thinking about Melissa Febos’ assertion, one that I agree with, that writing can be therapeutic and art, I also wanted to speak to the countervailing thoughts that I have. For one, how if writing is only looked through a therapeutic lens, which is definitely not true with this book, so I just want to make that clear, but if writing is only looked through a therapeutic lens, it can, at least for me, feel like it closes something down or flattens things that are particularly powerful about art. I notice this as a listener when you appear on more therapeutic-oriented podcasts, when you’re being interviewed by someone who’s a therapist or a psychologist or a cult expert rather than a writer. I’m sure these are good shows for their non-literature-focused audiences, so it’s not a critique of the show on its own terms. But when they use the word narcissist for your dad or the word cult for the commune, they aren’t wrong on either account. But it feels like in that context, it’s the conclusion and completion of something in a therapeutic lexicon, but where it really does very little in a literary one. For instance, in the communes, sexual freedom was everything. Children of the Cult goes into this in quite great detail. Children were encouraged to watch adults having sex. They were expected to want sex at an early age. In one commune, there was a beauty contest of the children’s prettiest genitals. Everyone knew what was going on, that children were being given up for sex, including the parents who were signing consent forms for them to be fit for contraceptives at puberty. We could say, as some of the cult-focused podcasts you’ve been on have, that everything I just mentioned is cult behavior. Who could argue that? But it becomes more complex if we step around this word, I think. Do we still think saying the word cult as an explanation and conclusion is illuminating if we consider the following? And these are just a handful of examples. The Affaire de Versailles case in France in the 70s, where three men, I think they were in their 40s, were arrested for sexual offenses against children aged 12 to 13\. Then all of these philosophers and academics and doctors and psychologists wrote in defense of the men, arguing the children had consented. Writers including Deleuze and Guattari, Roland Barthes, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir. Or consider also here in the U.S. Peter Yarrow of Peter, Paul, and Mary, of the song “Puff, the Magic Dragon,” who was convicted of molesting a 14-year-old girl when he was in his 30s, but then he was pardoned by Jimmy Carter, without Carter even notifying the victim before he did. Or in the UK in the last ten years, where the police are saying they’ve uncovered an epidemic of pedophilia in the 70s and 80s, with 4,000 allegations now leading belatedly to guilty verdicts since 2014\. To me, stopping at the word cult or the word narcissism reduces something in a literary work, which, circling back, especially if these same behaviors were widespread transnationally at the same time outside of cults, I’m not sure that saying it’s a cult gives us anything in that regard. It made me wonder if this were part of your wanting to push back against the purpose of writing being therapeutic, even when at the same time it often is and it’s a worthy goal to strive for. I think of you quoting Gornick when she says, “The writer’s obliged to go beyond the simple telling of the event to the meaning buried underneath.” Sometimes I wonder if the therapeutic language gets us there.

LD: Yes, I completely agree. There’s another wonderful quote that I often use, which is the James Baldwin quote about asking the questions beneath the answers. That really is the purpose of literature, good writing, in my opinion. I totally agree that the word cult and narcissism and any terminology like that, you know, another one that comes to mind is neurodiverse, which is something that a lot of people are using now, and of course it’s a very useful label in lots of ways, but it stops there, and it also is a very limited description of a spectrum of different conditions. And something as a creative writing teacher that I’m constantly doing is encouraging participants, writers, students to unpick these terms and certainly avoid them as much as possible, because they become clichéd in their overuse. It’s a problem, isn’t it, with the world that we live in, because I think commercialization brings terminology as well. Children of the Cult was not necessarily a title that we were that keen on for that documentary, because I don’t know if I’ve even used the word cult in Sins of My Father. I really tried to actively avoid using it, because at the time, it wasn’t a cult, and that wasn’t why people were seduced into it. It’s far more interesting to see it as the spiritual movement that they perceived it to be, to understand how they could have got entangled in such a terrible, I mean, from the perspective that we see it now, a terrible situation where so many of them were complicit with what was happening, but not realizing that they were. That in itself is a complex situation that is full of story. So yes, I agree with you that, of course, there is that therapeutic element to writing, but it doesn’t stop there and it mustn’t stop there. That’s why the craft and the important questions that come out of writing are so much a part of it.

DN: Talk to us about the photos at the beginning of each chapter, photos of notes, napkins, and envelopes, and also about how you employ writing exercises in the book.

LD: Well, the photos were my editor’s idea, really, because I talk about how, I mean, this goes back to that whole thing of writing as a means of survival, I suppose, or a means of better understanding oneself or working out conundrums that we come across in our lives. But any writer will relate to this, that need in the moment to write something down, an idea or a thought, or if you’re caught in some kind of complex upset and you’re not able to function, which was often the case for me when I was in my youth, in my teenage years and my 20s, and almost into my 30s, where I was so bound up in some horrible anxiety about something, often a man in my life, that I wasn’t actually able to function in my day to day. I wasn’t able to speak eloquently. I wasn’t able to engage. I wasn’t able to listen. In that state, in that anxious state, I would turn to whatever was close to hand, whether that be a napkin or an envelope, or if I was lucky enough to have a notebook or a ticket stub or the back of a receipt. I would scrawl my thoughts or my feelings. Often that would help alleviate that anxiety. So my editor was really keen to kind of include some of these scraps in the book. She was also really curious because I kept hold of all of my scraps. So I’ve got shelves and shelves of all my notebooks and my diaries, and my notebooks and diaries are packed full of scraps of paper and Rizlas, whatever it was that I was writing on. I suppose, again, that was just a really sort of nice thing that the editor had picked up on and acknowledged something that I just thought was normal. You know, I just thought, “Well, why would I not keep all of these scraps of paper?” But reflecting on it, I realised actually the reason I kept them was because I really honour it. You know, it matters. It matters. My relationship with my writing matters. My relationship with my past matters. It’s also an archive. It’s also part of something that becomes useful, particularly as a writer of nonfiction and memoir. It’s something also when I teach memoir that I tell my students that you are surrounded by your research because you are your research. So if you’ve kept your photographs and your diaries and those scraps of paper, you’ve got the beginnings of a book. You know, you’ve got the foundation really of a book. So, yeah, it’s something that I really value. I mean, I would be devastated if somebody came in and took all my notebooks away and tore up all my scraps of paper.

DN: What about the writing exercises?

LD: I just think it’s really nice to have craft books with writing exercises, isn’t it? It’s something that people can use. I think it opens up the readership to teachers as well. So it’s not just people who are wanting to become better writers. It’s also people who want to teach. I just wanted to share the writing exercises that I use. I enjoyed doing that part. Actually, it was really nice.

DN: I really liked it too. Well, one aspect that I particularly love about this book and also want to test your thoughts about is the role of imagination in memoir. So it’s returned to the bookmark from the beginning. Your memoir, Sins of My Father, opens with a line, “I imagine that the fog had lifted, that it was a bright morning when my father finally dragged himself from his bed.” Part of you writing that memoir involved asking your mom details about her life before you were born as well, and also looking at old photos and then imagining from those photos. So talk to us about both the use of novelistic tools in memoir and also about the role of imagination within writing the true story of one’s life.

LD: Memoir is not testimony, is it? It comes back to that question of what is memoir. Actually, at the beginning of my book, I tried to define what memoir is by saying what it isn’t. It’s not autobiography. It’s not the facts of the life. It’s the reimagining of a life is one way of putting it, I suppose. It’s an aspect of a life. It’s often thematically driven. Really, we’re trying to find the story out of the life, which again comes back to the moments of being that we talked about before. So there’s no way around not involving the imagination. We’re not writing anecdotes. We’re looking at the meaning beyond those anecdotes or beneath them or through them. So we have to engage the imagination to try to bring out what that moment, what that situation illuminates, what it has the potential to teach us. Also, I think the memoirs that I most enjoy are those where the writer is engaging their imagination and taking it beyond just telling us something that happened on that particular day in 1993\. So I think once we embrace that and realise that we can use our imagination, it expands the form immeasurably and it becomes this very flexible thing that can move into poetry, creative nonfiction. It can move into reportage. It can move into aspects of fiction as well. Coming back to the importance of honesty, that we need to be transparent when we are using our imagination. So we’re not just writing a fictional account of something. We are telling the reader, like I did at the beginning of Sins of My Father, that I wasn’t there that day, but this is how I am imagining it from the times that I was there before and from what I can piece together from that day. That can be problematic because, going back to Elissa Altman’s point, to a certain point, I’m imagining myself into my father’s skin, imagining what his front room looked like at that particular time in order to tell the story. I had to come to terms with that, whether that was, I felt was morally okay to do, and I decided that it was, as long as I was transparent about it, which I was. That transparency also is crucial to memoir because it gives the memoir that slightly more intimate sort of conversational tone where you introduce yourself as the narrator. You introduce yourself as a person who’s guiding the reader through the narrative. So, yeah, I’m absolutely behind people writing memoir using their imagination and being very explicit when they do, because that’s when the narrative comes alive. I think you can push too much into fictional technique. Dialogue is one of those things that I don’t know, I like memoirs that are written like novels, but I think they can veer a little bit too much into novelistic scene setting where you, as a reader, feel, “Hmm, is this really believable?” There’s something in memoirs that taps more into how memory works where, you know, you might grab at snippets of conversation rather than actually a full-blown dialogue between two people, which I think can be more effective. So, yeah, I mean, it’s using fictional technique within the confines of nonfiction, I’d say.

DN: Well, you probably answered my next question, but I’m going to ask it anyways, and maybe it’ll produce some more thoughts around it. But you write about using the imagination without fabricating. Obviously, that line is blurry. You talk about how Didion wrote about it snowing in August in Vermont. Then later she writes, “Perhaps there never were flurries in the night wind, and maybe no one else felt the ground hardening, and some are already dead, even as we pretended to bask in it. But that was how it felt to me, and it might as well have snowed, could have snowed, did snow.” Similarly, I think of when Sheila Heti interviewed Karl Ove Knausgaard and asked about a scene from his childhood in book one of My Struggle, which describes his mother on New Year’s Eve scrubbing potatoes, him putting an orange peel in the waste bin beside her, his dad walking down the drive, running his fingers through his hair, with her marveling at how photographic his memory was, a compelling aspect of that book for her as a reader, and him saying, to her dismay, “I made it up.” Then most provocatively and intentionally provocatively, John D’Agata, in his book The Lifespan of a Fact, which is co-written with his fact checker, and asserts his right to change the facts on behalf of what he calls the truth. The article in question, the one being fact-checked, was about a 16-year-old who commits suicide in Las Vegas. If this teenager was wearing, let’s say, a green coat, but it sounded better to D’Agata to say it was purple syntactically, that it created more of a music in a sentence, he would probably argue for it and call it so. If something that happened a month later in Las Vegas makes more impact by having it happen on the day of the suicide, all the better for D’Agata or D’Agata’s provocative persona in this book. For me, what D’Agata mainly proves is that there is a line. He’d argue that the rules don’t and shouldn’t change when writing about something important or not important. But I’d argue we’re beholden to our subjects and their lives, that D’Agata is beholden to this boy and his family if he’s going to write about them. It’s less clear to me with Didion and Knausgaard that it matters in the same way. But I guess I’d love to hear more about imagining without fabricating and what imagining without fabricating means to you?

LD: Gosh, yeah. Well, I think in the case of Didion, it’s about the feeling, isn’t it? It’s about what summer felt to her. When one conjures the image of snowing in August, it’s quite clear that that’s an emotional response to however she’s feeling at that time, in that place, what she’s observing. Yeah, I mean, imagining without fabricating, to be honest, I’m not sure that I’m capable of imagining without fabricating. [laughs]

DN: Like one way I might take your thought into what I just put forth is maybe Knausgaard could say, “I don’t know that it happened that way, but I could have legitimately imagined it happened that way,” which is different than Didion, who’s saying it probably didn’t snow, but it felt like it snowed. Then it’s different than D’Agata, who knows that it didn’t happen that way, but doesn’t care.

LD: Yeah, yeah.

DN: I don't know.