Madeleine Thien : The Book of Records

The Book of Records is many things: a book of historical fiction and speculative fiction, a meditation on time and on space-time, on storytelling and truth, on memory and the imagination, a book that impossibly conjures the lives and eras of the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, the Tang dynasty poet Du Fu and the political theorist Hannah Arendt not as mere ghostly presences but portrayed as vividly and tangibly as if they lived here and now in the room where we hold this very book. But most of all this is a book about books, about words as amulets, about stories as shelters, about novels as life rafts, about strangers saving strangers, about friendships that defy both space and time, about choosing, sometimes at great risk to oneself, life and love.

For the bonus audio Madeleine Thien contributes an incredible reading of the poem “Hold Everything Dear” by Gareth Evans. A poem that Evans himself wrote for John Berger. It joins a trove of bonus material, contributions from everyone from Omar El Akkad to Dionne Brand, Viet Thanh Nguyen to Danez Smith. To learn about how to subscribe to the bonus material and about all the other potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today’s conversation.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you by Street Books, Portland's community street library serving people who live outside and at the margins. Street Books offers books, reading glasses, information, and survival supplies to library patrons on the streets. They believe in the transformative capacity of books, both for the individual and the collective. Books offer access to ideas, education, and liberation. As Street Books marks its 15th year in operation, you're invited to join a movement of writers who believe in the power of literature and want to ensure access to good books for library patrons living outside in Portland, Oregon. Join writers like Omar El Akkad, Stephen King, Karen Russell, Dave Eggers, and many others by visiting streetbooks.org/writers. Today's episode is also brought to you by Rob Macaisa Colgate's debut poetry collection, Hardly Creatures, a powerful and beautifully written exploration and recognition of disability, accessibility, access, and intimacy. Taking the form, visually and metaphorically, of an accessible art museum, Hardly Creatures takes readers through nine sections that act as gallery rooms, shepherding them through the radiance and mess of the disability community. In the words of Chen Chen, "Never before have I experienced a book of poems that cares this firmly and boldly, this inventively and fully for its communities and for its reader." Playing with pop culture allusions, social media posts, and the infinite possibilities within queer love and deep friendships, these poems have what Jane Wong calls "radical realness." Reaching out and offering inventive, heartfelt insights, Hardly Creatures is a celebration of the disability community told through the lens of a visionary new voice in poetry. Hardly Creatures is out May 20th from Tin House and available for pre-order now. One thing that is centered in Madeleine Thien's new book and in our conversation are the lives of three writers writing in times of utter calamity and disaster. We also look at books as shelters, words as amulets, the work of others as places to gather for solace, but also places to gather ourselves to connect and resist, and about the life-changing risks people sometimes make for a stranger or for the art of another. I think about the way Maddie’s book is also about friendships across space and time, between the living but also between the living and the dead, when I think of her contribution to the bonus audio archive. A goosebump-inducing reading of a poem by Gareth Evans called "Hold Everything Dear," a poem that Evans wrote for John Berger. Maddie’s voice, Evans’ words, addressed together to John Berger, the gesture of his life, and the work within which we still gather. More and more, I've been sharing with supporters little islands of audio that feel like liferafts. Past guest Melanie Rae Thon recently wrote a poem as a response to listening to the most recent conversation with Hélène Cixous called "I love you and we will die," which she read for us. A listener who was recruited by the African National Congress in the 1980s to move from Canada to South Africa to set up an undercover safe house for activists reads her keynote speech for us, given to the North American Levinas Society, about this time in her life. And Maddie’s reading feels like one more node of solace and grace and connection and gathering. Thinking of connections and friendships, I also reached out to two past guests of the show: Dao Strom, who came on for her bilingual English-Vietnamese collection You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else, and Alicia Jo Rabins, who came on for her collection Fruit Geode, who also did the music for the intro and outro of the show. When I discovered that these two writers, songwriters, and musicians had connected when sharing a panel at the Portland Book Festival, and that they have since collaborated together, putting out the EP Wild Nights, I asked if they’d contribute. They’ve contributed a demo track from that album and another track that is on the album itself to the bonus archive. Whether you are a long-time or first-time listener, if you find these conversations are meaningful to you, consider joining the Between the Covers community as a listener/supporter. Get the resources with each episode. Join our collective brainstorm of who to invite going forward, and choose from many other things, whether the bonus audio, collectibles from past guests, or the Tin House Early Reader subscription, receiving 12 books over the course of a year, months before they're available to the general public. You can find out more at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. And now for today's episode with Madeleine Thien.

[Intro]

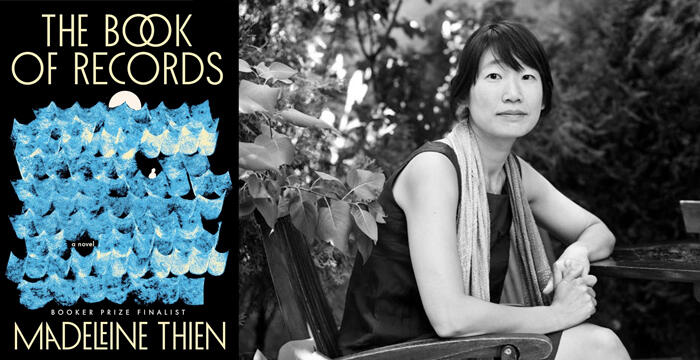

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest is the writer Madeleine Thien. Thien studied contemporary dance at Simon Fraser University and earned an MFA in creative writing from the University of British Columbia. In 2001, her debut short story collection Simple Recipes won many accolades, from the Emerging Writers Award from the Asian Canadian Writers Workshop to the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize for the best work of fiction by a British Columbian resident over the past year. Her debut novel Certainty, explored the secrets held by the protagonist’s father from his childhood in Japanese-occupied Borneo during World War II. Certainty was a finalist for the Kiriyama Prize, an international award given to books about the Pacific Rim and South Asia. Her 2011 novel Dogs at the Perimeter, set in both Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge and in present-day Montreal, was shortlisted for Berlin’s International Literature Prize and won the Frankfurt Book Fair’s LiBeraturpreis. Thien’s last novel, 2016’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing, followed two successive generations of an extended family in China, those that lived through Mao’s Cultural Revolution, and their children who became the students protesting in Tiananmen Square. Do Not Say We Have Nothing became a number one national bestseller, a finalist for the Booker Prize, shortlisted for the Rathbones Folio Prize, the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, and winner of both the Giller Prize and the Governor General’s Literary Award. Thien’s fiction has appeared everywhere from The New Yorker to Granta to The Penguin Book of Canadian Short Stories to The New Anthology of Canadian Literature. She was also the librettist for the opera Chinatown, created with composer Alice Ping Yee Ho and translator Paul Yee. Her criticism, essays, and multimedia work have engaged with everything from human rights to literary politics to state surveillance, to music, poetry, visual art, and more. She's taught literature and fiction in Canada, Hong Kong, Germany, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Singapore. And from 2018 to 2024, she was a professor of English at Brooklyn College, the City University of New York. Madeleine Thien is here today to talk about her much-anticipated new novel, her first since Do Not Say We Have Nothing, called The Book of Records. Claire Messud says of the book, “Rich, ambitious, and utterly engrossing, The Book of Records is at once a Borgesian meditation on Time’s overlapping folds, and a complex, moving feat of human storytelling.” Author and journalist Xinran adds, "A symphony of time, memory, and human resilience . . . [Thien] reminds us that art and ideas are often born in the margins, in the spaces where survival is a daily act of courage. Her writing compels us to reflect on our shared histories and the silent sacrifices made by those who dared to dream beyond their circumstances . . . As I read, I was reminded of a Tibetan proverb: 'The wind never forgets the mountain.' Thien's work, like the wind, gathers the stories of those who might otherwise be forgotten, breathing life into them and anchoring them firmly in our collective consciousness. This is a book that challenges, comforts, and inspires--a testament to Thien's extraordinary gift for storytelling." Finally, Maaza Mengiste says, “The Book of Records is a tale of exile and loss, of reinvention and longing. But most of all, it is a gifted writer's uncompromising vision of a world where the imagination has the ability to transform the rules of existence, and provide new mercies to those most vulnerable. Transportive, gripping, and tender, The Book of Records has come to us at a moment when we need it most. How lucky we are." Welcome to Between the Covers, Madeleine Thien.

Madeleine Thien: Thank you, David. It’s really a joy to be here.

DN: Well, first I just need to say that while I’ve been anticipating talking to you for years now, I also sort of felt accompanied by you during that time as I watched you in conversation with Adania Shibli as part of my preparation to talk to her for the first time, or you talking to her for a second time along with Layli Long Soldier in a three-part conversation, and me watching it in preparation for my second conversation with Adania along with Dionne Brand in our own three-part conversation, or for this conversation, watching you with another Between the Covers guest, Eliot Weinberger, who's a huge influence on my own writing. So first I just wanted to say how grateful I am that we are now talking not only through other writers who we share an admiration for but face-to-face.

MT: Yes, that moves me a lot. I mean, I think those particular conversations have meant a lot to me and you come to so many revelations only through that act of dialogue. I certainly feel that with Adania and Eliot, with Dionne, with so many of the writers you’ve spoken to.

DN: Well, it feels important to spend some time with the setting and the circumstance of this novel, both because it’s really unusual and because it’s so fundamental, I think, to everything that happens as we read. It both feels like a dream space and a space where very real people who are suffering very real things arrive. Nothing is really explained at the beginning, and in the spirit of the mystery of that, as we enter and encounter this in the book, talk to us about both the circumstances of Lina and her father arriving at a building called the Sea, and what they upon their arrival understand the Sea to be.

MT: Lina and her father have had to leave their home in the city of Foshan in China. At the time, Lina is seven years old. They leave behind a mother, a brother, and an aunt. And when they arrive at this enclave, which is only supposed to be a way station, a place to touch land for a moment before continuing their journey into the unknown to find a home, her father tells her that these buildings, which seem to wrap through and between one another and over and surround one another, he tells her that this building is made of time. It feels like when they enter, when they walk in one direction, they end up in the opposite direction, that it’s like following the curves of a knot that travels under and through itself. And this is going to be her home for seven years, a home that she initially thinks is temporary, and that becomes, in many ways, eternal.

DN: Well, we have questions for you from others, but unsurprisingly, the vast majority of these questions are about the Sea, the buildings that are the Sea in some way or another. So the beginning of our time together is going to be awash with the voices of other people, which in a way feels right because Lina and her father enter the Sea among many, many other people and their stories. The thing that differentiates our protagonists, as you’ve already mentioned, from most of these other people is that, unlike the others who arrive at this way station and quickly depart again, they remain because Lina and her father are waiting in the hopes that their mother and brother will eventually arrive. We don’t know the details, only that they’re from Foshan, China, that hundreds of thousands of kilometers of land have returned to the water, borders have been redrawn, and people have been displaced. We don't know if this is from climate change or from a dam. We don't know if the other people from every corner of the world also displaced, whether these mass movements of people are from war, climate, or natural disaster. What we do know is that when you are in the Sea and you look out the window at the actual sea, everyone sees a different sea, the one that they know. The rules of architecture in this building are strange, as you've already referred to. There are walls that are doors, hallways become rooms. Our first question for you is about this. This question is from the writer Maaza Mengiste, whose most recent book, The Shadow King, was shortlisted for the Booker and named a book of the year by many places from the New York Times to NPR. Salman Rushdie called it "a brilliant novel, lyrically lifting history towards myth." And Marlon James said, "The Shadow King is a beautiful and devastating work of women holding together a world ripping itself apart." So here's the question for you from Maaza.

Maaza Mengiste: Maddie, it's such a pleasure to be in conversation with you this way and thank you to David for inviting me to be a small part of this session. I've been looking forward to it for a long time. Maddie, we were at the Cullman Center together and I remember vividly your presentation there when you were still working on this book and you were talking about it with a small audience. You drew a graph of the book—or rather maybe a picture of how you imagined it would look. It took form without words and only with lines. You were drawing out what you envisioned the book looked like—or maybe it was even this building that your characters lived in. I kept thinking about this as I read your stunning novel. What came to mind again and again is this architecture of loss that I think you've created. But it's also something else, maybe a landscape of recovery, some form of shelter that the imagination provides for us. The word "mercy" kept coming up for me while reading your novel, and it was impossible not to think of landscapes of mercy and maybe architectures of rescue, and what our words and imagination might give to those who most need it. I don't know if this is a question as much as a way to begin a conversation that I hope we will continue together one day soon, but Maddie, could you talk a bit about these landscapes of mercy and maybe this sense of shelter and rescue that the imagination seems to provide in your characters, but I also think it is an ethos that you work with. Thank you, Maddie. Thank you, David.

MT: Thank you Maaza. It's hard to express it better than Maaza has. When I was writing it, when I was drawing those lines, when you're writing a novel, at least for me writing this one, you're sitting in the sea. You can't leave for one reason or another. And you're there to be with the people who come and the people who will depart, the people who come and never depart. I did think of it as a shelter. There's a Du Fu poem where he, during the horrific civil war that he lives through in the 8th century, where he says he wishes he could build a mansion of 10,000 rooms and whoever would need shelter could find a rest there, a place there, a place to breathe again. And I did think of the Sea as that. Initially it gives refuge to Lina and her father, but because it becomes their home, she also becomes the one who gives shelter, conversation, exchange, dialogue. She's so willing to talk to everyone who passes through, to make friends with everyone, even though she knows in a day or two they'll depart. I think the Sea was a way, even in catastrophic times, to ask what it means to love the world. And I think Lina's deepest struggle is to love the world that seems that it has taken from her what she holds most dear, which is her lost family.

DN: Do you think there's a difference between, or an importance—because I do—between, say, Du Fu's mansion of 10,000 rooms and the fact that this refuge, this sanctuary, or this architecture of mercy is a waystation? Like I think of a mansion as something solid and permanent. I mean, it isn't, but you feel something important about finding transience within something transient somehow.

MT: Yes. Perhaps when I read the Du Fu poem, I might not have thought of it in the sort of opulence or even something so firm. I think you're right, though, that this is a floating world. This is a temporary home that is itself returning to nature. Parts of the sea are no longer habitable. Parts of it can't be found again. I think once one has seen it once and leaves, it may not be there the next day. It's a beautiful question because I think in the back of my mind I also thought the sea itself was a waystation for the Sea. It is all those buildings that for a moment gave shelter, all those rooms, all those not even physical places but encounters, relations that give shelter before they dissolve back into movement, change, having to leave something behind. In a way, everything in the novel is on one level maybe a refuge from time, but also a refuge from forgetting, a refuge of care.

DN: Yes. Well, even within Maaza's spatial and architectural question, I think there is the unspoken subtext of time and the relationship between space and time. As you said, the buildings themselves, according to the father, are made of time. Most of the arrivals, they depart quickly, but our protagonists are waylaid for years within this space-time building. Which makes me think of a presentation you gave a decade ago at Simon Fraser University with Rawi Hage on Arrival, the description of which says, If the world is in a constant state of motion, expansion and collapse, then all arrivals are a moving rest, a hesitation in motion. Arrival is never passive. It is not neutral and it is never innocent for those who arrive or those who are preceded. Arrival could be imagined as the continuous evolution of the self, a form of renewal or reinvention. We seek it out, anticipating an ending. But what of those who never intended to arrive? As Italo Calvino writes, 'But how have I managed to arrive, when I have not yet left?'” And I also think of the Walter Benjamin line later in this book. "History is the time of now perforated with fragments of redemption." So we have two questions for you about time and/or space-time, and I'm going to introduce and play one and then introduce and play the second and you can answer them both as you see fit. The first is from the Chinese writer Yan Ge, who has a long-celebrated career publishing books in Chinese, but her latest book, called Elsewhere, longlisted for the Story Prize and a New Yorker best book of 2023, was the first that she wrote originally in English. Matt Bell's praise of this book evokes something of both space and time when he says, "In Elsewhere, her stories are both expansive and precise, their range of subjects and approaches suggesting few bounds to the subversive pleasures her stories might deliver. I suspect that even now Yan Ge is racing ahead of us lucky readers, off to explore the outer limits of possibility." So here's her question.

Yan Ge: Hi Maddie, I hope you're well. I've been meaning to write you a proper long email to talk about The Book of Records since I finished reading it earlier this year. I haven't managed to do so not only because life got in the way but also I feel this novel, in its extraordinary complexity and multiplicity, beckons a reader's silence. I felt so strongly right after reading it that what you've brought into actuality is an ideal novel. The kind that can only exist in its exact pages, an inexhaustible and ever-evolving image that defies summarization and resists being reduced into quantifiable talking points. Having said that, there's one thing I'd love to hear your thoughts on, which is the recurrent theme of time and space. At the beginning of the story, the father explains to Lina that time is a piece of string, and when you twist it into a double coin knot, it turns into space. I was struck by the image and wondered, later, if by creating this novel, setting up paragraphs, chapters, and stories from different points of view, and juxtuposing these narrative spaces in particular orders, you're leading us to a specific kind of time. I don't know if you'd agree with my interpretation, but I'd love to hear you talk a bit about how you considered the notions of time and space and the relationship between them while working on this novel. Thank you.

DN: So the second half of this omnibus question is from the writer and historian of science James Gleick, whose first book Chaos: Making a New Science was a finalist for the Pulitzer and the National Book Award, who has also written a biography of Isaac Newton, and whose last book, Time Travel: A History, is in Joyce Carol Oates's words "an exploration not only of the (theoretical) phenomenon of time travel but of our understanding of time itself." The The Millions adds, Gleick’s “hybrid of history, literary criticism, theoretical physics, and philosophical meditation is itself a time-jumping, head-tripping odyssey.” I'm thinking of the line from your book that Yan Ge foregrounded: "If I took a piece of string and folded it over and threw itself to form a double-coin knot, the string is time, and the knot is space, but they are the same." In that spirit, here’s a question for you, nested within Yan Ge's question about time from James Gleick.

James Gleick: I want to ask you how you think about the great mystery of time, as a thing we experience in the world, and as a challenge to storytelling. Your new book bends time in strange ways. It's a kind of time travel, for sure, but it's not like any time travel book I've read before.

MT: [Laughs] Wow, it's so wonderful to hear their voices. It's really hard not to be emotional, actually. [laughter]

DN: You can be emotional.

MT: Yes. It's happening. [laughter] You know, I think for me there might have been many, many ways of thinking about time as space, because it was such a long process writing the novel, the nine years. Different things happen along the way of writing it, and one of those was being at the bedside of two people who meant the world to me as they left this world. One was my father. My mother had passed away years earlier, and she had died away from home. And my father, I was at his bedside through the last weeks of his life and right at the end. My best friend Y-Dang Troeung, who passed away when she was 41, and her husband and her cousin and I were at her bedside for those last 10 days. And I think in those last weeks, when you have the privilege and the heartache of accompanying someone through the passage or to the door of the passage, time is something else entirely. It's a universe there. It's endless. It's infinite. It surrounds you. It is your sense that the person you love is made of time and is being returned to another time, an infinite time. And you have this feeling of the vessel that each of us is. I think through the years of writing the book, the building, the people, the histories that merge and come together and break apart, it was, in a way, to pay tribute to these many scales of time that we carry and the way that it lengthens and folds, the way a tiny moment can seem to encapsulate more than we can ever face. [laughs] In some ways in writing the novel, there was the consolation that each person who passes through for a moment who talks to Lina for a few moments or a few hours or for seven years, they are all these pieces of something that is fitted together in a wholeness that is just a glimpse of another wholeness. In a way we could almost say that in the novel, time and space don't necessarily bend or change. It's just that it's vast and we're always moving through it and it's always moving through us. I think it meant a lot to me to be able to spend so many years just thinking about the way we hold things and place them within other things, and then within other things, and then within other things.

DN: Well, to stay with that, and also to stay one more moment with these three questions and questioners about space and time. In one interview about your father passing, you mentioned that one of the last things he wanted was to go home. And that was impossible to do. I'm thinking about Yan Ge's notion of your book being an ideal book and your saying that you envision the Sea, the building as a refuge for the sea, the ocean, and also the Sea is right next to the sea and this question of representation, I guess I wanted to ask a question about home, I mean because in a way I wonder if the ideal book is a home, and if something about going home isn't about geography.

MT: I think this is really true. I think you sort of named something that is very much what the novel desires, because Lina will not go back. Her father will not go back. It may not exist anymore. And yet, maybe I wanted to find the part of home that as we make it, we understand what it means to make belonging, and not just for ourselves, and I think as a writer, sometimes we search for it in language, also knowing that that's a tenuous ship to set sail on. [laughs] Because it's when we make language, we're really entrusting it to another. It is something we're conveying, but also something whose meaning we have to let go of, in a sense, as it's received, as it's heard, as another also steps into that small boat and maybe we find it in other people's words and other people's lives in that little string that connects us. I find it hard to put words around it actually, it's hard to name this thing. It is a very unarmed kind of question in that, you know, "Why is it so hard to love this world?" and yet also this world is our only home. And to care for it, we must love it. It's the only way to care for something, is to love it.

DN: I think you've started to or have begun to answer my next question, which is sort of about what you describe as this tenuous ship of language, because there's one other element that, like everything we've discussed so far, is also introduced quite early that we need to establish, I think, before we can dive into the meat of the book. That is the three books that Lina and her father take with them. They had a series of books at home called The Great Lives of Voyagers and when they fled, Lina's father took Volume 3, 70, and 84. Lina wished he had brought number one about a Ming dynasty sailor or number 23 about a 14th century Moroccan wanderer but the books they have are the ones on the philosopher Spinoza, the Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu, and finally one on Hannah Arendt. And mysteriously, there are three other people at the sea who are also waylaid like them, waiting for others to arrive, and each is a sort of contemporary avatar or channel of these three historical figures. Lina and her father and these three others form a community in the Sea. When they departed Foshan arriving and then leaving one besieged place after another, her father would read from these books to his daughter. But at the Sea, she discovers, as she reads the books themselves for the first time, that her father made things up as he read to her to extend and prolong the story. She also discovers that her brother has written within the book, adding things like the word voyage over and over again in the Arendt book, the word voyage made of the two Chinese characters for vessel and ocean. So two family members have already interjected in some way or another, altering the story. And similarly, when Lina reads aloud to her new chosen family, she herself finds herself changing things in the storytelling, but also discovers that her three mysterious compatriots know quite a lot and can identify the book's shortcomings and mischaracterizations. Then they themselves tell the "real" story of the person within the book. So much like the buildings of the Sea, the essence of the book and perhaps even the essence of the selfhood of these historical figures is not confined within the architecture of the codex of a book or perhaps even the form of a human body. The story keeps escaping the book and returning to it. It moves from oral to written, remembered to invented. Much like a building, written words I think seem fixed, but your book unmoors them, both unmooring the building and unmooring words. I wondered if this sparked some thoughts or if you could speak more into what feels like a philosophy of books, and perhaps even a philosophy of self.

MT: There are so many layers to your question and interestingly, layers to my memory in terms of the way these layers came to be in the novel because maybe one of the effects of writing something over such a long time is you're constantly erasing and leaving traces and then building it up again and erasing and retelling. I had always been interested in this gift that our parents give us. If we are, again, sorrowfully but fortunate enough to be able to walk them towards an ending, their ending, they leave us the wholeness of their lives, the pattern of their lives, a large part of it of which we have no knowledge because we're born only partway through their lives. But I've often thought about that patterning that my parents in some ways entrusted to us, their children, in that they wanted both to give us an example and to set us on an entirely new course and also they wanted us to remember but they wanted us to forget and they wanted us to know them deeply and they wanted to be seen by us but on in another way they knew that they know that they'll always be a mystery to us. I think that that relationship with this gift they gave me of who they were has probably found itself and found its way into this novel in the ways that Lina tries to tell the story of her father or the stories are told to her and she retains of the lives of figures from history. She receives them in book form, but they come alive in the retelling and the reimagining and the effort to remember and the necessity of forgetting. That's where they're really alive. She's aware too, I think, it's possibly something that stretches across my book. I'm always drawn to the storyteller who's not visible and that we only know by the choices they're making, by the things they're forgetting, by the moments where they hesitate, by the ways they reconfigure things. I think the idea of knowing someone by the way in which they tell the story of another has always felt to me like a deep intimacy.

DN: Well, it's not a surprise that this book is a decade in the making, given that for most of the book, we are in the worlds of Spinoza, Du Fu, and Arendt, deeply enmeshed in your vividly rendered portrayal of three entirely distinct and different historical time periods and settings. It's really an amazing feat. But let's start with Spinoza and I'm hoping you'll paint for us the picture of Spinoza's Amsterdam. Maybe place it in history a little bit for us. What the moment historically of his life would be like in that city in that time and how his family came to be there in the first place because it seems like an unusually dynamic place where for instance you say that in the neighborhood, Spinoza lived, you'd hear chatter in Portuguese, prayers in Hebrew, poems in Spanish, and jokes in Dutch.

MT: So this is Amsterdam of the early 17th century. It is what is often called the Dutch Golden Age. It's the Netherlands that has colonies, it's the Netherlands in which a tremendous amount of wealth is being extracted from elsewhere and passing through these ports and sold elsewhere. Spinoza's family is Jewish, they had to flee Portugal, his mother tongue is Portuguese. I believe his father first goes to France and then down into the Netherlands. They live in the Jewish community of Amsterdam. Spinoza is, I believe, most biographical accounts believe he was a very pious child and young man, very learned, extremely intelligent, full of questions. We know not a tremendous amount about this time in his life. We do know that first his mother died when he was still a young child, and then within a fairly short time period, his older brother, his older sister, and his father, and his stepmother all died. And Baruch Spinoza buried them all, and then was the guardian for two younger siblings. We know that sometime around these years, when he was still in his early 20s, he was excommunicated.

DN: Let's stop there for a second because I want to return to that and ask you to stay with the excommunication for a moment in a little bit. But let me ask you a more abstract question about you and Spinoza versus a biographical one. Because I think what I'm going to ask you, at least on the surface, feels like a simple question. What is it about Spinoza that you love and that attracts you to him either as a person or as a thinker? But actually, even having read the book, I don't think I could guess what your answer is going to be. That is because it seems to me that Spinoza's work is metabolized by people in very different ways. Not only has Spinoza influenced everyone from Freud to Marx to neuroscientists, not only did Nietzsche consider him a precursor to his own thought, and not only did Einstein say, "I believe in Spinoza's God, the one who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists," but I ended up watching or listening to quite a few philosopher roundtables about Spinoza in anticipation of today. The thing that amazed me the most was how little these purported experts agreed upon how to frame him, even in what would seem like basic ways. They debated whether he was a materialist or not, whether he was a pantheist or an atheist. One roundtable agreed there was nothing mystical about him at all, that he was a rationalist, but another talk was entirely framing him as a mystic. Many of the philosophers talked about how he isn't focused on in school if you're studying philosophy, but sort of lightly mentioned and then moved on from, which was my experience when I pursued my undergraduate degree in philosophy. We read the very beginning of the Ethics, but then spent way more time and attention and detail on Kant, Descartes, Hume, Locke, and others. I had no idea whether that was unique to my program or not, but it sounds like it echoed the way these philosophers described their own educations. Yet, he seems to endure, and his influence continues to renew itself in new ways and spheres. His renaissance at any given moment could be due to his notion of panpsychism, that everything in the world contains consciousness, or how he imagined and argued for a sort of secularism that was almost unfathomable at the time. But it could be many other things. So talk to us about your own attraction to him. What about his life, or perhaps life story, or what about his philosophy has become this enduring engagement with Spinoza for you, an engagement in this book, but also outside of this book too?

MT: Yes. I fear it will be a disappointing answer. [laughter]

DN: How come?

MT: I first began to hear the name of Spinoza in my early 20s because the person I was in love with was in love with Spinoza and had been attached to Spinoza from a very young age and this person saw Spinoza as an atheist and for them Spinoza offered a way to think about the weight of our existence in a brief and mortal life that is part of an eternity, but we are not part of eternity. Can you hear this recycling truck going by outside?

DN: Yeah, it's fine though. I mean, people will hear it, but you know, it happens in every conversation.

MT: [Laughs] Do you know why it's making me pause this? Because I feel like as I'm talking about Spinoza, this truck is saying "That's not correct. That's not correct." [laughter] Okay, and then I lived in the Netherlands. I strangely felt the presence of Spinoza and it opened up this curiosity for me about him, so I just started to gather Spinoza things over there. I never had any idea that I would one day write about him in this way. But his books, his letters, especially Ethics, I mean his book Ethics, I just kept coming back to. It's a very, very difficult book, and in some ways, on first glance, it's very opaque. It's written in this geometric style, there's propositions and axioms and scholia and all kinds of things and yet in the proof that he's trying to make about the eternal and the mortal and the nature of God or the nature of nature, on the one hand, there was a part of me that was working through the philosophy, and on the other hand, there was a part of me that kept thinking, "Who is this person for whom these questions were so crucial that he spent his life looking for the method to transmit a way for us to know the very rare truths that are so precious and that should be available to all of us." As much as the philosophy, I was interested in the person who devoted their life to trying to find a way to communicate something he felt could bring us—it's funny, you know, I mean I think there are works that come to you when you're young and you don't know how to make sense of them but there's something about them that won't let you go and you just return. I mean, it's interesting about when we were talking earlier about home and what that might mean if it's not a stable structure, if it's not a place, and I do think in some ways some of these texts, these books, these questions became a kind of place that I returned to. They marked time. In a way, those works we return to, they keep time for us. When we return, we're altered. Yet our questions are not necessarily different. We might just come at them from a slightly different angle that time allows.

DN: Well, I wanted to share the thing that attracts me the most to Spinoza. But I'm going to do it in my typical roundabout way, but it will eventually end with a question to you. So I'm asking for your indulgence at the moment. But it has to do with the relationship of body to mind or body to spirit. It's something that I think about a lot. Partly because of the way for millennia, Jews were characterized as fundamentally material, of the body, and unable to transcend and experience the spiritual. You see this, for instance, in Michelangelo's depiction of Christ's ancestors in the Sistine Chapel, who in contrast to the Sibyls and angels are shown with ancestral torpor, to borrow the title of a book that is about these ancestor figures. They're sluggish and inert, sometimes hunched or grimacing, but always with a sense of heaviness as if they lived on a planet where gravity was ten times the gravity of Earth. That was already a long-standing notion in his time, but it's still pervasive in modernity where, for instance, Carl Jung could talk about how the Jew is far too conscious and differentiated to be pregnant with the tensions of unborn futures. In other words, trapped in the world of the known and the seen, where he could conclude because of this, the Aryan unconscious has a higher potential than the Jewish. Or Rudolf Steiner, the founder of biodynamic farming and Waldorf education, saying Jews, along with the Chinese, were a sign of racial stagnation and that the fact that Judaism still exists today is an error of history. That notion is the most pervasive version of this today. Something almost seen as self-evident by many, or as a truism, even in the framing of the Old Testament and the New Testament, is that Christianity is an evolution, an improvement, and completion of Judaism, that it makes Judaism vestigial, that the angry God is replaced with the loving God, selectively ignoring the books of Isaiah, Ruth, Ecclesiastes, or the Psalms, which are a big part of Christian liturgy, or "love thy neighbor as thyself" in Leviticus, or the punitive threat of fire and brimstone in Revelations. I bring this up to argue against or trouble the notion of progress or evolution between religions, because whatever good and goodness Christian doctrine has introduced into the world, I would argue there's a trade-off, a cost or a loss, like with anything, not particular to Christianity. I think it's with relationship to the body, its relationship to the spirit, the aversion of the body as unclean, or that virginity and celibacy bring one closer to godliness. The introduction of original sin, where in Judaism when a human repents, they're returning to the inherent wholeness and goodness of who they are meant to be. They aren't having something divine come in and remove something inherently bad. Having sex on the Sabbath is encouraged and seen as a good thing. One cannot cause harm to another and then receive forgiveness and absolution by appealing to an invisible God in Judaism. You must confront the person body to body, the person who was harmed. And the "heroes" of the Hebrew Bible are not good or bad, but inseparably both, which to me is a compelling form of storytelling. All of this to say, I've always thought the renewed interest in Spinoza, in contrast to the supremacy of Descartes and Cartesian duality for many centuries, especially at a time when so much of the world is moving off of the body, virtualizing, extracting, and externalizing consequences to either an afterlife or to an unseen people elsewhere, is that in contrast to Descartes, the body and mind are not separable for Spinoza. The mind-spirit is beholden to the body, which feels quite Jewish to me. None of this is in your book, nor in any great detail his family's flight from forced conversion in Spain and Portugal, where many were imprisoned, tortured, or even burned at the stake for these sorts of notions. But one thing ironically, given what I've just said, that is central to your book, which you began to talk about, is Spinoza's excommunication from the Jewish community. Excommunication is so rare in Judaism that I think many Jews might not even know it is a thing. But I mean, if you have thoughts about what I just said, great, but what I was hoping you also talk about is, and primarily talk about, is why he is seen as such a threat, the fear he invokes, and what excommunication means or looks like when he is banished from the Jewish community in Amsterdam.

MT: The way Spinoza writes about emotion and the body, it's almost the way he talks about emotion is the way we talk about how one color becomes another color. It's this continuous movement, that these precise states of body that give rise to this continuous movement of emotion through us and is the substrate of consciousness as it moves through these layers from our responses to things to what we map as our rational and conscious thought and then the actions that we choose and so on and so forth. He really is attentive to what is human. It's clear that when Spinoza is mapping the intensity of these emotions and where it leads us, where it drives us, what it makes us long for, how we act against our own interests in the hope of trying to satisfy this desire or hunger or want, he sees all of this in a continuity of life and he doesn't separate us from it. I think there are small passages that hold very briefly what happened to his family in Spain and Portugal and the almost continuous exile. And then to come directly to your question. I think that that is in a way the threat that Spinoza posed is that as a young man, he began to believe that the holy books are the stories that men tell, that the Bible is one of these books, that these are fictions, that God is not as we imagined him, that even the kinds of hierarchies and order that a God above would generate—if you take out what holds that hierarchy together—you begin to envision another way in which we are in relation to God, our nature, and to each other. And this, I think, for the community was frightening in the sense that yes, he was a heretic in their midst, but he was a heretic in a Christian country as well. That questioning of God and the order is wider than the Jewish community, and I think there was great fear about what it would mean to harbor a heretic amongst them and what kind of disorder this could open up. Especially in this Amsterdam of this time, there's a very rebellious youth movement. There's a lot of rethinking of what the political order should look like. So I think it taps into many things very deeply connected to anxiety about the safety of the community in Amsterdam, yes.

DN: You have this wonderful essay called Spinoza’s Rooms that can be found in an anthology called The Gifts of Reading. And I want to read a couple of things from it to connect us back to time and space, but also as a preface to a next question from someone else. So cobbling together a couple different passages about Spinoza’s day job as a lens maker, you say: "Spinoza’s field is geometric optics, the branch of physics concerned with properties of light as understood through the laws of reflection and refraction. Spinoza made lenses for both microscopes and telescopes. A telescope is a point of view. Just like that, two lenses carry Saturn’s moon—nearly 1 billion kilometers away—right up to the eye. 1 billion kilometers collapsed in space and time, so that Saturn feels as near as the cup of coffee on your desk. The greater the distance of magnification, the further we see into the past; light takes time to reach us. Our most powerful telescopes, like the Hubble, receive images of things as they were 13.2 billion years ago. To the question, what are we within the scope of the universe, Spinoza’s contemporaries intuited an answer that was cataclysmic for faith, religion, philosophy, politics, science, art, selfhood. 'For in the end,' writes Pascal, 'what is a man as regards nature? Nothing compared to the infinite, everything compared to nothingness, a medium between nothing and the all, infinitely distant from understanding the extremes.'” Our next question is from the novelist and poet Moriel Rothman-Zecher. His most recent book, Before All the World, was a 2022 NPR Book of the Year, and Adina Applebaum of the Jewish Book Council says that, “At its core, Before All the World considers one essential question: what does it mean to remember the past while still imagining the future? . . . Its most striking accomplishment is its invitation to the reader to become a part of the novel’s chorus. What will you do, it asks, now that you’ve read this story?”

Moriel Rothman-Zecher: Hi Maddie, it’s Moriel. I wanted to ask you about friendship. So recently, some weeks ago, you and I had a conversation in which you told me about your process of writing down by hand all of Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics. And I was so struck by that. I’ve been thinking about it nonstop and thinking about how to weave copying full texts by hand into my writing practice and into my friendship practice. So my question is about friendship. I was struck by that act as a kind of act of radical friendship between you and Spinoza, between the living and the dead, between writers today and writers hundreds of years ago and writers hundreds of years from now, and I wonder if you can tell me more about what it feels like to write about friendship, whether that is friendship between Hannah Arendt and Walter Benjamin, friendship between Spinoza and Du Fu and Hannah, friendship between the living and the dead, friendship between writers throughout time and across time and outside of time. Just also to say here that I’m so grateful for our friendship and grateful for the opportunity to get to extend our friendship into this form of conversation. Thank you for gathering these.

MT: So wonderful. Thank you for gathering these. It’s just beautiful. You know, I didn’t know this when I started writing, but as the novel filled in its pieces or sort of went on its journey, it did become clear that friendship becomes this most powerful act of love and courage and resistance. It’s certainly true when I placed all the stories side by side, or as they began to weave through each other, that it became clear that all of them are at times, many times, sometimes, saved by another, and none of their work would reach us had these acts of friendship not occurred. And Moriel asked about that idea of friendship across the centuries between the living and the dead. I was always struck by Hannah Arendt writing about Rahel Varnhagen and saying she was my best friend even though she had died a hundred years ago before her. I often felt this with the three figures who were moving around in the Sea, that they were amazed that we wanted to sit with them, even if we didn’t always agree with them, even if we might have quite serious critiques of some of their ideas. But even then, the desire to value the teacher, to value the teaching, and to understand what it was that each of us might be looking for each time we sit with a text, with a person, with another human being, I only really feel like I was with Spinoza when I, over many months, copied up Ethics. I understood then the way the geometry would work on a person’s mind, that it is such a step-by-step process, that text. One thing really must be understood before one moves to the next proposition. One has to draw the angles of the triangle and the measurements and understand what a triangle is before one can begin to “constellate” it with other things. That’s very much how Ethics works. It is this seed, that everything that it contains is in it from its first axioms, its first propositions, and you can kind of unfold them and see how that all works. But to go back to friendship, I think the joys of this novel are in those relationships. They’re in the casual conversations, the fleeting conversations, the chance encounters, the person who steps in to save the life of a complete stranger, the person who knows the visa that is being handed to them is probably forged and they return it to that person and tell them to go on with their journey and to continue. The thousand little things that people do, a piece of bread, a bag of figs, a job, shelter on the road. I think I thought I was writing about historical figures, philosophers, and poets who had meant a lot to me, but I found that I was writing about the worlds that gave them shelter.

DN: Given that Moriel brings up this activity of copying, I want to ask you about the book's title and about the notion of a book of records. Because in your last book, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, the different generations of the families are connected by the manuscript of a novel called The Book of Records, whose chapters have been copied and hidden behind walls, under floorboards, and handed down. That book is hidden and precious because it's a narrative that doesn't conform to approved Chinese history. A book that you say has no beginning, middle, or end, one of an alternative China where the reader recognizes mirrors of themselves and which they write themselves into, which feels very similar to these great Voyager books and the Book of Records we're reading now. In the Spinoza section of this book, Spinoza's father's name is entered into a book called The Book of Records, the Livro de Bet Haim. There's another line in the book, "Here at the sea the written word was considered a kind of amulet. Travelers hired calligraphers to copy things, poems, prayers, genealogies, into a book of records." So talk to us about this traveling title and this notion, this reappearing book, this notion of a book of records, which seems to also involve copying. [laughter]

MT: Yes, I must say I'm not sure anyone's asked me so many questions that have made me fall so utterly silent for so long. [laughter]

DN: There's one interview that I left most of the silence in, and it's with Teju Cole, and everyone comments on that conversation. Because I normally just remove the silences, but your silences are like his silences, they're full, you can just feel the thinking and the thoughts and the feelings.

MT: Yes, it's like the question has to sit with me. It's working its way through me. It has surprised me the extent to which the idea of the Book of Records has become a bit of a life raft, maybe because more and more I'm haunted by that question of what are we doing. And in Do Not Say We Have Nothing, it comes near the end of the novel. The daughter, whose father we know from the beginning of the novel took his own life, and the daughter, near the end of the long years of gathering that she has done to understand the people that her father loved, the world her father loved, the world he didn't save and the parts that he did try to save, she wishes that he had known that someone else would keep the Book of Records, that he didn't have to be the one to carry it all his life to the end. She wished he'd had faith that someone else would come and carry it with him, for him, and take that responsibility. I think in this new novel there's a playfulness around the keeping of the Book of Records. There's the historical story retold and reimagined and breathed into life again by a girl who I think no one would imagine would be the inheritor of these stories, but who understands this is part of her lineage now. Not because it's the only thing she had, but because it's the thing she chose to love. And she also tries to keep a record not of her own life, but of other lives, hoping that should her family come across this book, they will recognize what it is, they will recognize her by what she chose to save.

DN: I love that.

MT: And to me that's been my sort of roundabout way of trying to answer this question of what are we doing? What are we doing here? And what are we the vessel for? What is it we hope will survive into the future? What can we give passage to in the brief time that we have? That is that Walter Benjamin idea of wanting to breathe something into life again in the hopes that someone else will pick it up, carry it, take on the responsibility of carrying the Book of Records, which as a collective, can only be done by the collective, requires myriad stories and myriad ways of telling it and seeing it. But knowing that it's a collective inheritance, both the painful parts and the ones that give us a way forward.

DN: Well, there definitely is a sense across the three historical narratives in this book of books as amulets or talisman, much as your act of copying feels like almost a magical act that facilitates a sort of transmission between bodies across time. Not only the three rescued books from the Great Voyager series brought with Lina and her father in flight, but everyone is fleeing carrying books. At one point, Arendt is carrying her husband's manuscript disguised and wrapped in ham. When she flees over the Pyrenees at great risk, she can't give up because she needs to reunite with her suitcase with the manuscript of Walter Benjamin's last writings, her close friend who has just committed suicide. She also has to leave a companion who can't make the journey over the mountains, and she's gifted by this person a volume of Proust and quotes the lines from it. “One has knocked at all the doors which lead nowhere, and then one stumbles without knowing it on the only door through which one can enter---which one might have sought in vain for a hundred years, and it opens.” So Arendt is fleeing with Proust and Kant on her body. We spot Spinoza on Benjamin's bookshelf at one point. All in all, it feels like gifting books and fleeing with other books creates this connective tissue and that they are evidence of a connective tissue, that they are signs of love and reasons to go on living. Similarly, the Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu managed to carry more than a thousand of his poems with him, even when he and his family were displaced. Spinoza may have had it bad, his family displaced to Amsterdam because of Christian persecution, then excommunicated by his own community, then the plague returning to the city, and as you mentioned for various reasons, his mother, brother, sister, stepmother, and father have all died. But Du Fu's life is equally fraught. His own child dies of starvation. He lacks status, can't find a job. The major anthologies ignore him. He dies penniless. His life is full of famine, war, and poverty. And yet some say his status today in Chinese literature is similar to that of Shakespeare and the Anglophone world. So I was hoping you could talk to us about the China of his day, the catastrophic civil war that within seven years caused two-thirds of the population of China to be killed, disappeared, or displaced, and also talk to us about why you choose Du Fu versus other poets, whether a contemporary like Li Bai, who you've written about elsewhere, or a poet from another era in China entirely. What is it about his poems or his life story that made you want to center him specifically.

MT: He was another person whose work just accompanied me for decades that I kept returning to almost like the tide keeps bringing you back. I think that's how it felt returning to the works of these three and others, but certainly these three. And where I write about him here, it's in the years leading up to the Civil War. When he's lived most of his life already, but the greater part of his poems, I believe two-thirds, will be written in the years of the war. And those are the poems for which we know him best. But I think I wanted to write about an empire which seemed at the height of its power, of its cultural production, of its wealth, of its sophistication and cosmopolitanism that was stretching its borders farther and farther and is in fact at the precipice of the abyss. I wanted to write about this erudite brilliant poet who only wants to serve the government, who believes that's his function, who believes that's where he can do his greatest good, who believes that this is how he fits in to a harmonious system and then in the course of his life even though he's probably one of the most meticulous, rigorous in terms of form in terms of his poetry in the forms that he was using, he's extremely rigorous and precise, and yet he's writing very much about the very every day. He writes about places he visits, getting drunk, spending time with friends, the little antics of his small children, missing his wife, things he's growing in his garden. It's wonderful. It's somehow through the rigorous form of the poetry he invests everything with both familiar meatiness and life and something that becomes increasingly transcendent and it's happening all at once. He sees and he records the utter collapse of his world and he spends decades trying to go home, and he never does. He felt to me like someone who was speaking to us from the future, someone who wanted to believe that goodness could come from the order in which he came of age, while also watching as that order consumed itself in corruption, in being filled by, it comes up in the book again about people who don't seem to believe in the reality of the world, who seem to see the world as a plaything for various interests, and then who will pay the price when chaos ensues.

DN: Well, leaping forward to the China of the contemporary moment of the novel, whether that's modern China, future China, imagined China, there's a section where we get to glimpse the circumstances of why Lina and her father are together, but not with her mother or brother, and to talk about it would be a spoiler. But it does connect to long-standing interests of yours when engaging with China and Cambodia and your past books that I think we could talk about more generally. For instance, when you were in Mumbai five years ago, you talked about your long-standing interest in communism in Asia and also in utopian societies as a site of violence, and as an aside you mentioned in that talk about how Mao was a good poet and famous for all the books that he carried with him on the Long March. You also talk about how the Khmer Rouge wanted to do in four years what Mao did in thirty. At the National Library of Australia in 2017, you talked about how allegiance is not supposed to be to the family, but to the state, that the family unit is seen as a threat because of this, and that when you were young, you were willing to sacrifice for the collective and for ideals, and that your books on Cambodia and on China were grappling with your own idealism. You talk of your interest in how these ideologies that require sacrifice for a just society become so remarkably unjust. And you talk about one of the cities in Calvino's Invisible Cities, that is the just city, and yet this just city contains a seed of unjustness that is growing and growing, yet within that unjust city, there is a just seed growing and growing, so creating this endless double helix. You pose the question, "Is it the human condition that our goodness and our violence are intertwined?" So thinking of this and bringing us to the contemporary moment, talk to us about, if not how this question manifests in The Book of Records specifically, about your current thoughts and questions in this realm, around this mystery about how societies with their purported ideals, including what you just described about the Tang dynasty, the goodness of the order, and then the self-consuming nature of what happens, that can bring about unspeakable violences that might be unrecognizable from the purported ideals of the people committing them.

MT: Yes, I think when I was writing about Cambodia, particularly the Khmer Rouge years, it's what totalitarianism requires, which is, you know what Hannah described as loneliness, rootlessness, atomization. We have to be cut off from one another. And probably Cambodia has shaped so much of my thinking, both in what happened and the way it's been remembered or not remembered and of course it was called "the sideshow of the Vietnam War." It was 2.7 million tons of bombs dropped by the US on Cambodia secretly because the United States was not at war with Cambodia but was trying to target North Vietnamese supply lines that ran through Cambodia. Of course caused massive terror, horror, displacement, loss of agrarian land, starvation, migration to the cities, to safe places, and sent people into the arms of the revolution of what was then considered the resistance of resistance, the Khmer Rouge, to fight a war of liberation and a war of liberation that became so extreme that it imagined that it could make Cambodia completely self-sustaining without any foreign interference whatsoever, because, I mean, one could understand the argument of what foreign interference had done, because also Phnom Penh Center was ruled by an American-backed general after a coup. So we know all these things from many other places and many repetitions of these histories. All this to say that when the Khmer Rouge time ended, a genocide had occurred. A genocide that would not be legally—no one would be legally—would be held responsible for it until just a few years ago in that tribunal. I'm trying to knit different parts of your question together. I have a feeling that the years I spent writing about Cambodia opened up these really difficult questions about how one might, first, save oneself in the moment but also about how one might save one's soul and I think that is a recurring question in both Dogs at the Perimeter and Do Not Say We Have Nothing. There's survival, there's also trying to protect the ones you love, and then there's the question of what the cost of doing that might be, and the fact that every moment you're faced with a choice that maybe guarantees no one's survival but also threatens co-opting you into the violence that is spreading and then there are many reasons why we would tell ourselves that violence is the only option. It's just that it's never-ending. It's the lit match that simply just goes from match to match to match and at the cost of the things that actually make life worth living, that one can live with oneself, face oneself. I'm going at this in a very roundabout way, but I do think that the literatures that we have in which there are impossible choices, but also there are choices, are very important. Because in some senses, as we navigate catastrophe, the feeling that we have no choice, it is maybe another facet of oppression. It's also true we can't always save ourselves. It's that sort of terrain that people face, but also that we're forcing people to face. I do think often of Hannah Arendt's, we need to stop and think. We need to stop and think about what we are doing. In all the modes that we have these conversations—writing literature, writing books that take a decade, intervening in the public space, the things that we try to do to say no, not in our name—for as long as we have these choices, I think we have to make them. I mean, I think this answer can show you just how afraid I am, to be honest, how difficult I find this moment in which we live and how I feel we need to come at it with our ethics, our philosophy, our action, our literature, our hope, our friendships, nothing is separated anymore, and nothing ever was. But every facet of that touches another.

DN: Yeah. To return to Du Fu and his impossible situation just for another moment, outside of this book when engaging with Du Fu, you often quote the translator David Hinton. In your essay, Poems Without an 'I', you say, Hinton observes that Du Fu, as his world collapsed, was trying to awaken language itself, to include all of experience equally, rather than limiting it to privileged moments of lyric beauty or insight, and thus to express a relentless realism, synonymous with consciousness itself. Perhaps hearkening back to Moriel's question about friendship, it feels like your new book invites me to make connections or friendships across time and space. For instance, when I learn how Du Fu wants to render all experience equally—not just transcendent moments, but ordinary ones—I think of Spinoza's single substance theory. When you quote Claire Carlisle's intro to George Eliot's translation of Spinoza's Ethics, "We are to God as waves are to the ocean," I think of Hinton's characterizations of Du Fu. Similarly, when Arendt's father explains his notion of free will or the lack of free will, I feel like he is speaking words Spinoza could have himself said when he says, "A stone hurled into the air suddenly wakes into consciousness. It has no memory of what set it in motion. All it knows is what it senses, the wind, stars, birds, trees, and other stones. Every second is unanticipated. The trajectory of the stone was determined long before it woke by the force and angle of the throw. Yet it experiences each day as if nothing could have been foreseen. Is the stone free?" And that makes me think of Eliot Weinberger's poetry in his latest book The Life of Tu Fu, a stanza that goes, "All things do what they do: Birds swoop to catch an insect. Moonlight breaks through the forest leaves. Soldiers guard the border. I am trapped in this body." Yet, despite the way these different worlds transmogrify into each other, you say in that essay that because of the radical differences between Chinese and English, that Du Fu's poems are all but untranslatable, even as you name and love multiple translations of him. One of the translators you name then later takes issue with your characterization in a post that he does. You, in the comment section of his post, hold your ground, you argue that you see translation as an art, as a creative act. And like all art, it involves an untranslatability of the thing it is engaged with, that you weren't arguing that the endeavor wasn't of value, but of the opposite. And in that spirit, I want to ask you about research and research and the imagination, the way you render not just Spinoza's inner life, his engagements with Rashi, Maimonides, Descartes, but also him at the pub with little details like how people are smoking tobacco laced with belladonna, and Spinoza working the lathe grinding lenses, or the thrill and goosebumps of how you bring alive the love affair between Heidegger and Arendt, and her friendship with Benjamin, or her time in prison, or her time on a freight car, or in the Paris velodrome. The book is really miraculous in these moments. On the one hand, I think of the lines in the Spinoza Lens section that no action, however small, is minor, that every detail foretells the future. But then I think of a line in a different section, "Would I prefer to be remembered wrongly if it meant some trace of my life would persist? Could a person in the memory of that person diverged so far that recollection itself becomes a kind of portrayal?" and Lina's father saying, "The only way to remember is to forget, to let time fill the story up and create it all over again," or how you've said your most successful novel, your last one, is the least satisfying because the pain is so close to your own origin story. So all of this begs the question of method and process and ethos of leaping through time and space and breathing life into these other figures, and I would love to hear a little bit about research in light of all of this.

MT: Yes. In a way, you're the dream reader, because of the way you're able to knit across all the pieces, the way you kind of have understood its prismatic structure and hope. And it's true, that line that I have distributed to Hannah's father is a Spinoza. The description of the stone is from a letter that's Spinoza, right? So I have embellished it a little and added--

DN: I love it.

MT: Yes, but yes, that is absolutely Spinoza. The research, yes, untranslatability. Wow, there is so much in your question. [laughs]

DN: But the research is directly confronting untranslatability, right? You can know so much and yet know nothing.

MT: A fiction writer, I think in their heart must believe that there are truths that only the imagination can reach. They're not the only truths, there's many ways for us to find that rare and precious thing. But the thing itself is rare and precious. And the leap of the imagination, when one has been grounded in all that one can find of the factual, I think those two things are deeply connected for me. Without the grounding of the immersive research, or just the being with them in their time—it's how I almost think of it—it's only then that the imagination grows from the very real. I sometimes thought of it, yes, definitely as translation, and sometimes as transposing, and the way you would move music into another key or that you would move things up an octave or, yeah, into another key. I felt that it is the same, but the singer is different, the range of the singer is particular, and so we need to transpose into their key, and it creates other harmonics. And then I think in the end, I was really interested in that idea of how you move three-dimensional, say the night sky, and all that light is coming to us from different times, and two stars beside each other, one may be extremely young, one may be tens of billions of years older, but on the page of the sky they look as if they're side-by-side or emitting the same intensity of light. That translation of the multi-dimensional into the flat surface of the page I think was something I was drawn to, to take these figures from centuries apart and distant, but to move them into this sheet of paper.

DN: That's amazing. I love that. [laughter] Well, my favorite sections of The Book of Records are the Arendt sections. She's the person I think you've written the most about and spoken the most about of the three outside of the book. For instance, writing about her book Men in Dark Times, you say, "Men in Dark Times remains in me like a corridor branching off to many unlit rooms, and in each room there is a person thinking to him or herself, a person creating work, a person in constant engagement with the ideas of others. The beauty of this book is, for me, that we are all in these rooms, and only in the discourse, in this passionate engagement, can we find our way to one another." And then as a guest on the Hannah Arendt Between Worlds podcast, you talk about how you love the intimacy with which Arendt writes, bringing you along with her, where there's even a sense of suspense as if you too are thinking alongside her. You talk about how she does this intimate thing without relying on or sharing her personal motivations for why she is thinking what she is thinking, nor sharing the surely terrible memories that haunt her, which nevertheless you can feel in her work. You say this quality is very important to you, to witness a woman occupying a space in this way, refusing to enter the public sphere through personal vulnerability. But this is only one of many things you share there and elsewhere that attract you to Hannah Arendt. So, the impossible question for you right now is to talk to us about the importance of her for you, [laughter] whether her actions, her self in the world, or the qualities of her thought that she becomes one of the principal characters in The Book of Records?

MT: Yes, I think that earlier I say that you read from quite a long time ago, the one about the passageways and corridors in different rooms, that Men in Dark Times. When I hear it now, I can see that there's a faint blueprint of the sea.

DN: That's why I read it, because it reminded me of Maaza's question about the architectures of mercy or the architectures of recovery.

MT: Yes, these things lay their traces in the work early on and you don't really even recognize them or know, but there's something about the way it's formulating and configuring itself in your head that it's going into something actually real, a reality that you will perhaps bring to the page in some way. I feel like I've had the longest relationship with her of all three and deepest—not deepest, but deep in a different way because I turned to her a lot when I was writing about Cambodia and I had a very particular relationship with her because The Origins of Totalitarianism is such an important book, remains such an important book. It's all of it, but that last section about—near the end—about what it does to the inner world of a person to live in totalitarian times I think resonated across everything I knew from Cambodian friends and from witness accounts and from the histories. And it was a complex relationship because even though her subject was totalitarianism and authoritarianism and political freedoms in Men in Dark Times, she never writes about Asia. It almost never comes up in her work even though monumental things are happening—Vietnam War, what's happening in China, Cultural Revolution. So I always had this almost like I was always with her but out of sight of her. And that's actually in a funny way the relationship of a novelist to the worlds they're creating. You're so close to them. You live with them. You listen. You hang on to their every word. You're thinking about them all the time, but they can't totally see you for different reasons, or you've blended into the environment around them. So in a way, I felt I had a lot of permission to move into something that I think is a transgression for someone who admires Hannah Arendt so much. She was very private. And she very consciously kept what was private, private. Yet she herself wrote so incisively and movingly about the lives of others—little biographical sketches, essays, the biography of Rahel Varnhagen, and so on. The kind of brief answer to your question about Arendt—gone in this long tangent—is that because I lived with her writings for so long, her ideas are very alive in me. I'm kind of aware that in some ways, they are very much embedded in the choices that I make, in the ways I think about what it means to speak in the world, what it means to appear in the world, that she would put it, what it means for poetry to both hold, to create meaning. What is her line? To create meaning without—I used to always have that line at my fingertips. It's something, lines of creating meaning without making it rigid, without detonating, I think is what she's moving towards saying. But also how the moment the poet can fail to see and contribute to obscuring what needs to be seen. She judges, but she also thinks a lot about what it means to judge. And she also, I think, accepts judgment. I think when she knows that a piece of her writing has failed to contemplate an aspect of something, failed to address it, failed to see, I think she actually does engage in that conversation. This only one can know from the huge amounts of private letters we have of her, she does face things. I admire that she maintains her faith that the world is not in her, in another person, in a third person. It's between us all. And that is why we have an obligation to it. It is the world between us. It is the world that none of us can fully encompass. It is the one that we are actively shaping with each and every choice we make.