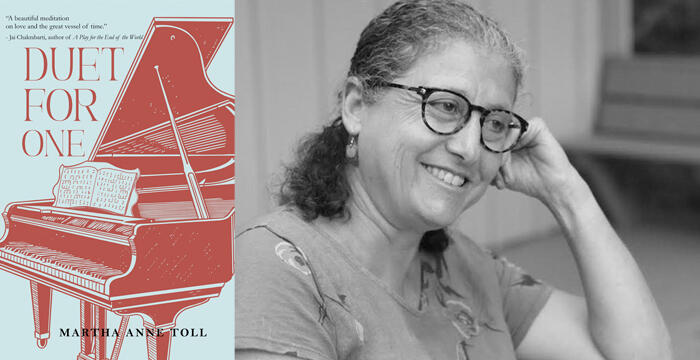

Martha Anne Toll : Duet for One

Today’s guest is writer and critic Martha Anne Toll. Through a discussion of her latest novel Duet for One we explore the perennial mystery of writing and art-making, namely how to render something that lives beyond representation, and how words can become a vehicle to evoke what words themselves cannot adequately describe. In this case, we look at how to bring music into language, the experience of making it and hearing it into the realm of words. We explore Martha’s lifelong journey toward becoming a writer, through music and law and social justice, ultimately debuting as a novelist in her sixties. And how her mentorship as a musician affected and shaped her writing life, from craft and form to failure and perseverance.

If you enjoyed today’s conversation consider joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. Find out about all the rewards and benefits of doing so at the show’s Patreon page.

Finally here is the BookShop for today’s episode.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you by Carrie R. Moore's Make Your Way Home, a stunning debut story collection that spans Florida marshes, North Carolina mountains, and southern metropolitan cities as it follows Black men and women who grapple with the homes that have eluded them. Says Deesha Philyaw, "Carrie R. Moore’s arresting Southern stories pulse with the kind of intimacy, beauty, and intensity that the best art conjures. Her characters and their voices linger and arouse, long after their final moments on the page." Says Megan Kamalei Kakimoto, "Make Your Way Home is a collection that moved me to my core." Elizabeth McCracken adds, "It is a book that has the force of life itself, all its hurts and love and betrayal, the little intimacies, terrible mistakes, reconciliations, moments of transcendence, the ways we can and cannot change. It is an astonishing debut." Make Your Way Home is available now from Tin House. Before we begin today’s conversation with Martha Anne Toll, one that in part engages with questions of how to render that which escapes words on the page in words—in this case, music—let me mention some of the musical contributions to the bonus audio archive from past wordsmiths on the show. Most recently, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson gave a sneak peek of a track from her upcoming album, Live Like the Sky. Two past guests, Dao Strom and Alicia Jo Rabins, have collaborated on an EP called Wild Nights, sharing with us both a track from the album and a demo of another track. Canisia Lubrin and Nam Le both contributed soundscapes. Most elaborately, the brilliant and bonkers contribution from Johanna Hedva, where they created an extended sound experiment of moans and groans that they recorded while on book tour, mixed with sounds from outer space, whether that of solar flares or black holes. Of course, there are a lot of words in the archive too—interviews with translators, craft talks, supplemental readings, and more. The bonus audio is only one thing to choose from if you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. Regardless of what you choose, every supporter gets the resources with each episode of what I discovered while preparing, what we referenced during the conversation, and where you could explore once you’re done listening, which in this case includes Martha’s companion playlists and musical book recommendations, among many other things. Every supporter is invited to join our collective brainstorm of who to invite on the show going into the future. You can check it all out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today’s episode with Martha Anne Toll.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I’m David Naimon, your host. Today’s guest, the writer and literary critic Martha Anne Toll, earned a BA in music from Yale and a law degree from Boston University. She began her career in corporate law and as an honors attorney for the U.S. Treasury. But despite its rewards, she felt, in her own words, disconnected from anything that mattered and began to volunteer at a homeless shelter established by the activist Mitch Snyder, who had staged hunger strikes in front of Reagan’s White House on behalf of the homeless. Toll continued her work in law and continued volunteering at shelters until, ultimately, she was hired to run a social justice philanthropy. As the founding executive director of the Butler Family Fund, she developed and led programs to prevent and end homelessness, abolish the death penalty, and combat racial injustice and inequity in the criminal justice system. She established a partnership with the Oak Foundation in Geneva and London to achieve similar aims. As a book reviewer and as a critic, Toll has published widely, from her interviews of writers at Washington Independent Review of Books, to her opinion pieces and reviews at The Washington Post, to her many years of book reviewing for NPR, foregrounding writing by everyone from Garth Greenwell to the first English translation of Marguerite Duras’s first book. Toll is also a member of the National Book Critics Circle and serves on the board of directors of the PEN/Faulkner Foundation. All along through the years, Martha Anne Toll was writing herself, finally having her breakthrough when she won the 2020 Petrichor Prize, which resulted in the publication of her debut novel, Three Muses, a novel that went on to be a finalist for the 2023 Gotham Book Prize, alongside past Between the Covers guests Hernan Diaz and James Hannaham. With a starred review from Kirkus, Pulitzer Prize winner Paul Harding says of Three Muses, “Martha Anne Toll’s three muses are those of song, discipline, and memory. In this beautiful, dark novel, she has choreographed the mysterious ways these forces push and pull and shape the lives of her characters – lives of terrible loss and precious if dismaying survival – through their dissonances, harmonies, deprivations and recoveries. A meditation on history, music, the catastrophic inheritances of the Holocaust, and the so common, painful hiddenness of hope itself, Three Muses captivates the reader from the first page to the last.” Kiese Laymon adds, “Martha Anne Toll’s Three Muses is so surprisingly soulful. The surprise doesn’t lie in the existence of textured prose that explores dance, music, love and time in wholly different ways; it lies in how that textured prose actually creates a new time signature wholly dependent on practice and discipline. This is phenomenal writing. It just is.” Martha Anne Toll is here today on Between the Covers to discuss her new novel, which, like Three Muses, is published by Regal House, called Duet for One. Writer, translator, journalist, and dance and opera critic Marina Harss says, “Music, and the near impossibility of doing justice to it, is one of the books' themes. Another is the great disappointment and loss of purpose that comes from not measuring up in some way, of “failing” in one’s own eyes and the eyes of others. Toll shows great finesse in the way she describes the actual technical aspects of playing, both the piano and the violin and viola. Especially fascinating is the way she describes how musicians shape sound. Through her words, you experience the effort and control that go into playing music at a high level, relinquishing all other things in order to unravel its mysteries.” Past Between the Covers guest Pauls Toutonghi says of Toll’s latest, “Music—like love—is a challenge to both the senses and the intellectual mind. In this poignant and attentively-written novel, Martha Anne Toll writes about the triumphs and sorrows of these two elements of human life, and considers how they might intertwine. Duet for One unfolds with symphonic sweep, each of its movements revealing deeper layers of emotion and insight into the central characters. The great works--works by Brahms, Beethoven, Schubert, Paganini, Mozart, Smetana--serve as the backdrop for Toll's clever and intricate storytelling.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Martha Anne Toll.

Martha Anne Toll: Thank you so much. That was a beautiful introduction. I appreciate it.

DN: So before we talk about Duet for One, I thought it would be nice since the listenership of the show leans heavily toward writers and art makers, aspiring writers and aspiring art makers, and of course, readers who are particularly curious not just about the writing, but the writer behind the writing. I thought it would be nice to spend a little time with your writing life prior to the publication of Three Muses and the arrival of Martha Anne Toll as a debut novelist at 64 years old. It wasn’t like you decided at age 60 or at age 62 to be a writer, then worked on a manuscript, and then published it as Three Muses a couple of years later. There was a lot of long-standing hope, uncertainty, rejection, and grief before these last couple of years of success as a now twice-published novelist. So give us a little peek behind the curtain of how things were for you with your work in progress before winning the Petrichor Prize?

MAT: Well, I could start at the very beginning, which is I grew up in a household that was steeped in books. My father was a really good writer, although he was a lawyer. My mother was a professional copy editor. I was well into my 50s before I really started to think about that my father's mother became virtually deaf at his birth. So his speaking voice was stentorian and clear. Like all of his siblings, he was a fanatic about vocabulary. So I have no formal training to speak of, but I feel like the training I got at the dinner table and with the red pencils on my papers was completely indispensable and taught me everything that I know. Both parents were also fanatic readers. So if I look back, I was writing my whole life. I always had a diary. I wrote plays when I was seven years old for me and my three sisters to perform like that. I really love fiction. For years, years and years, I kept thinking I have all these words but I don't have a plot. I think that I was reading like a writer, like thinking about how books were written, saving vocabulary words, doing the things that we all do from a young age. As a lawyer, I had extremely writing-intensive jobs. So I think one philosophy of mine is that if you write, you write. It doesn't matter if it's memos for your board of directors or the great American novel. I think it's you're developing your chops. The floodgates opened when my mother died very suddenly in 1999, and I still can't totally put this together, but she was a person who really did not believe in giving her children compliments. She thought it would give us a swollen head. It was a philosophy of hers. She didn't believe in praise. But for whatever reason, she always told me I could write. Now I see that as pretty much the biggest gift she could have given me. So I started writing and it's like a gusher. [laughter] It's been like that ever since. It took me a little while to figure out plots, et cetera. Then I had lots of interaction with the publishing industry. I, over time, had three different literary agents based in New York City, and none of them could sell the novel to a publisher so that they went unpublished. So I did feel like I was grieving, even though I didn't feel justified in that. But it was a lot of disappointment. I don't really understand how writers become professional writers in their 20s, because it's brutal. I mean, I definitely had some defenses by the time I started submitting things. I had a family, I had a job that I loved. I stayed in that job a long time, because I loved what I was doing. Even though there were tremendous time constraints on my writing, I could tell that my job is like good for my mental health. I went to the organizing meeting of the Washington Independent Review of Books in 2010. That got me started on the book critic journey. That was incredibly helpful. I mean, I love books, and I love sharing what I love about books. It was really nice to start getting published. I'm not proud of that, but it's true.

DN: Is that part of the perseverance, the starting to book review at a time when the novels weren't being accepted?

MAT: Absolutely. It was very affirming because I was able to publish. There was a time I was publishing two reviews a month, it was just great to start getting my writing out into the world. Also, I have a lot of philosophical beliefs about sharing books and the fact that a lot of books never get reviewed, a lot of classes of people never get reviewed, all those things. So I felt like it gave me this wonderful platform. It's extremely important to my development.

DN: Well, your debut, Three Muses, was actually your fourth book. You started it in 2010 and you started the book we're discussing today, Duet for One, over 20 years ago. You've talked about the innumerable drafts you wrote of each of them, how you were able to get an agent, as you just mentioned, three different times, when it really is no small feat to get one at all, one time. How you divorced the final agent when they wouldn't submit it to independent presses. How you started noticing that Three Muses ended up as a finalist several times when you submitted the book yourself, unagented, to book contests, until it finally won one. You've talked about how in the early years, during times of intense rejection, how you found yourself in a period of grief, and yet you kept writing not only more books, but you kept revising the rejected ones. You've also pushed back against a lot of advice that you felt was wrong. For instance, editors telling you to get rid of the three muses in Three Muses. [laughter] In the book we're discussing, feedback that you should nix the character Victor because nobody is going to want to read about an older man. I bring this up because I'm curious about both the perseverance and how you nurture and maintain it and about your inner fortitude to push back and say no, when I could imagine, given all the no's you yourself have faced for so long over many years, that the temptation to capitulate or defer to another's instinct might actually grow stronger over time. I do wonder, and you might have even nodded to this, if part of this is an upside of being older, but I also partly think about it because the book we're going to discuss in part is about discipline in the face of adversity too. Something I suspect you've faced in your pursuits outside of writing, and obviously you've faced in your pursuit of writing.

MAT: Thank you. Those are two really important questions. So in terms of perseverance, I have three things to say to that. The first is I was so sensitive, vulnerable to rejections. I don't think that ever goes away, but you do get a tougher skin over time. But I never stopped writing. It was never enough to close the book and forget about it. So I did start noticing that, but I felt like a boing machine, like boing back. I had two other things that I did off and on. One was to get a charitable contribution every time I got a rejection. That could get very expensive. [laughs] But it was good. It was like, let's send some love out into the world. That's a better thing to do than think about the rejection. The third thing was the advice that I got somewhere probably in the 2018s, that's the best advice, which is to go for 100 rejections a year. That just feels completely right. I was finally able to turn the tables around and say that acceptance is the rare, rare exception and that rejection is just normal in writing land and every writer experiences it and there's no shame involved and fancy writers experience it and not fancy writers so it makes it somewhat easier. It doesn't make it easy. You're always upset when you get a rejection. So that's how I feel about the perseverance. But the main thing was I just didn't stop and I thought this has got to mean something I guess because yeah. In terms of the pushback, I would say my trajectory was not so much age-related, but experience-related. When you're first starting out and people send you things, you're like, "Oh, they must be right, I must be wrong." There were one or two really destructive people involved, but by and large, people were being constructive, but they had ideas that didn't work. That took years and years and years for me to develop my own voice and say, "No, this just isn't working." I mean, a concrete example of that is I had a developmental edit that suggested telling Three Muses chronologically. I probably spent two years working on that. Then I didn't like it at all. So I had to undo everything. So, to be able to question the feedback that you're getting, I think it's a matter of experience. The world is very, very subjective. Every reader is going to have a different opinion. So it takes a lot of time to figure out what you agree with and what you don't agree with.

DN: Well, let's talk about Duet for One. The opening two lines of the book, "Adele Pearl was dead, vanquished by ovarian cancer. Adam and Victor shivered at her graveside." These two lines introduce us quickly to three of the four most important characters in the book, as well as the central loss from which the story unfolds and then refolds itself. Can you flesh out this family a little bit for us, introducing us to Adele and Victor and their son Adam, and where Adele's death leaves Victor and Adam as we begin the story?

MAT: So, Adele and Victor are married to each other, but not only that, they share a full professional life together. They are a married two-piano team, and they're very famous, and they travel the world. They each made the decision not to pursue a solo professional life. They both teach, but this is their life. Everybody's based in Philadelphia, which is my hometown. It's where I grew up. For Victor, the remaining member of the duo, he is going through catastrophic grief at the death of his wife, but he's also going through the loss of his career. So he's got a double whammy. Adam is their son. He's in his late 30s, and he has a professional violin career. He's an only child. His experience is much more fraught. He's at his mother's graveside thinking, "I don't feel very good. I didn't really know my mother. I felt she was distant and absent." That's a very difficult place for him to be in at her graveside. I think that a really, really, really important part of this book is Adam doesn't understand his own grief. He had this preconceived notion that he would feel really sad or bereaved. What he feels is really conflicted, a bunch of anger, a bunch of questions. He doesn't really understand who his mother was. As the book goes on, he realized, "Well, I really didn't know her." Then so there's grief around that. I've been interested, the book's only been out about two months, two and a half months, but readers have really resonated with his own confusion and his having to come to understand that grief is not linear and it's not pleasant and everybody grieves in their own way. He has to find his way through his grief. I think that he has to come to understand the full complexity of his mother. That's part of his grief. That's part of how he goes through it. He also pretty early on starts to think about the fact that he's had many, many girlfriends, but he has really not had success in love. He hasn't really figured out how to sustain a relationship.

DN: So the idea of a couple whose entire career was based on their life playing duets on piano together, where Victor loses, as you said, not only the love of his life, but also the only way he publicly made music, comes from you coming across a real-life scenario of reading the obituary of the pianist Lilian Kallir, who, like Adele, dies of ovarian cancer. I know that that influence of Lilian's life on Adele's life goes no further than these few details. But in reading about Kallir, I discovered that long before she died, she developed what is called musical alexia, where she began to lose the ability to read a musical score. She first discovered this on stage while performing, but was able to complete the piece from memory. This became worse and worse, where for years she relied increasingly on memory to play pieces, and her repertoire shrank because she couldn't learn new pieces through reading sheet music. It also quickly became a more general alexia, not being able to read intermittently, to recognize words and sentences, and eventually not being able to recognize images and objects as their complete selves, but only as their component parts. Yet increasingly, she could learn music by ear. On top of that, her vision was perfect, and she could write completely normally, even if she couldn't reread the letters she had written. So eventually, she writes to Oliver Sacks for help, and her case became part of the book, The Mind's Eye. I bring this up as a preface to talking about the mysteries of music, what I imagine are the particular difficulties of putting music into words to conjuring a musical experience in a semantic space. I don't want to suggest that writing about dance, as you did in your first book, is easy. But I imagine it is easier than writing about music because of the visual component of watching and then describing what you're watching in physical space. Whereas music, when we listen to a piece of music, we not only don't ask what it means the way we do with something composed of words, it also reaches places far deeper than where words, or where the eye, can travel. Where in Kallir’s case, when you can no longer conjure your capacity to read, you can still conjure the music both through memory and through the ear, bypassing the eye. I think of how when Victor loses love, when he loses Adele, he also loses his mode of music making. That feels right to me because love feels also something like music in the sense that love is an inadequate word for something that can't be described. I imagine you must have devised strategies of how you want to render the musical experience on the page in words. I wonder if you can talk about them, how you came upon them, but also if there are ways music is put into words in books that you find particularly unsatisfying, perhaps as an example of a counterpoint to what you aim for when you try to evoke music in words.

MAT: So first of all, I just have to back up a little. I did zero research on Lilian Kallir on purpose because I wanted to develop my own characters. So I never heard that. That's completely fascinating. I don't even know how to think about that. [laughter] I've read a fair amount of Oliver Sacks, but I've not read that book. It's really, really interesting. Gosh, I'm going to have to go back and think about that. It's like a meta meta. [laughter] One other comment I want to make on that—and I think this must be true for most novelists—there are multiple inspirations for all of my novels. So I had this concept of wanting to write a musical book set in Philadelphia, but I didn't have a framework until I read that obituary. So that gave me a framework, even though, as I said, I was purposeful about not doing research. So that's completely fascinating. So, yes, I have never made the comparison of whether dance or music is harder to get on the page. But let's just say music is hard to get on the page. We all know it's ephemeral. It doesn't last. I also think that either music or dance, or possibly both are the earliest forms of human expression from hundreds of thousands of years ago, and so it's primal to all of us. And I think that if we live in the 21st century, we've had contact with music. And I think for many, many, most of us, if you have not a musical bone in your body, you still are evoked deeply emotionally by music. I'm talking any kind of music. I'm not a musical snob. So you know that's different for different people. And it's like a sense of smell. It's extraordinarily evocative. When you hear a piece of music you haven't heard for a long time, you're often able to associate it with something important in your life, sad, happy, whatever. So it has this extraordinary ability to evoke memory. So I had some dos and don'ts when I started. The don'ts were to try to stay away from words that are typically used in music criticism that are overused, that we would expect. I do write with a thesaurus. Look, there are really no synonyms for music, but things that you would think about; lyrical, harmonic, melodic, all those things. So as a writer, I felt that I had to figure out other types of metaphors to describe it because those words are so overused. I also wanted anybody who wanted to, to read this book. I wanted the readers to not need a classical music education. I mean, it makes me a little sad that people think you have to know something to listen to classical music or go to a concert. While I'm here, I have a Spotify list on my website if you want to hear the music. I really believe in trying to open this world up a little, but not just open it, pull up the curtain behind it. Because I think that you could say this about soccer or football or brain surgery, it's a lot of perspiration before there's inspiration. So playing a musical instrument or singing is a tremendous amount of physical training, and it's a physical act. For wind players, that has a lot to do with breathing and getting control over your breath. Some wind players do something called circular breathing where they can exhale and inhale at the same time. I'm a former violist, so viola, it's your left and right hand that have a lot of physical training to do, extremely different skill sets in the right hand, which holds the bow, from the left hand, which plays on the keyboard. There are obviously also tremendous mental challenges. It's a whole new language, alphabet. Interestingly, in Western classical music culture, we read music. But I think that's a bit anomalous for music around the world. I think many people don't have a written, recorded way to learn music. People learn it from ear and from imitation. So in my book, I wanted to get to the physicality, and I was trained that way. My viola teacher, Max Aronoff, to whom the book is dedicated, kept a plastic hand on his desk in the studio, which was like, I think, from an anatomy, probably a medical anatomy class. He can take the lid off and show you the tendons. In string playing, your ring finger and the middle finger are called your third and fourth finger. Those tendons are crossed in a way that presents tremendous physical challenges for string players, because your ring finger has trouble doing things because of that. So he used to like take the lid off his plastic hand and show me that. Then go home and tell your mother you got an anatomy lesson. [laughter] There's a lot of tremendous endurance in your fingers and muscular development. In your right, your bow arm, tremendous wrist coordination. I think many string players would say the bow is equivalent to human breath, which a good singer, we don't hear them taking a breath. You aren't meant to hear bow changes. You know, the bow goes up and down. You're not meant to hear that either, but it takes extraordinary skill and physical training. So a lot of my book, or not a lot, but there are scenes describing the physical aspects of making music. So that was one way that I got on the page to try to transmit what that is, just as if you were on a baseball team, you would do warmups. It's really no different. The other thing is to associate it with the evocation of emotions, which is incredibly hard. Basically that's the challenge of writing a novel or writing anything about emotion. It's challenging. [laughs]

DN: I think one thing that's really interesting about reading the physicality of musicians is I feel like it allows the reader to fill in imaginatively what the music sounds like.

MAT: I hope so, I hope so.

DN: Yeah, rather than telling us at length what the music being produced sounds like in a strange way, counterintuitively, I think almost focusing on how the music is produced and then twinning that with, as you said, the emotional register or maybe around memory also. It allows us to create a music.

MAT: I feel really happy to hear that because that's obviously my intention. My teacher, Max Aronoff, I mean, I think there's a ton of imitation in music, he had a spectacular instrument. But he also is the best violist that I've ever heard. I've heard a lot of violas. He just had this beautiful, beautiful sound. It was so much part of my training and I think the training of all of his students to hear that sound and try to imitate it. I think imitation is a huge amount of training in the arts. You know, I think that early painters, they go to museums and they copy paintings. It's one of the reasons that I am violently opposed to the use of the word derivative. A lot of critics, when they want to criticize a work of art, they say it's derivative. It really irritates me because all of the training in the arts is to become derivative, to learn what the masters have done before you. I mean, Mozart listened to Haydn. We don't go around saying Mozart's derivative of Haydn as an insult. That's how he learned his craft. So the sound that your teacher makes is very important. I was going to say it's instrumental. [laughter]

DN: I love that.

MAT: You're producing sounds. So I wanted to comment on your saying that you filled in, in your head, what was on the page in Duet for One. I am trained as a lawyer, and it took me a little while to figure out that novels are not legal briefs. If your reader doesn't understand what you're talking about, that's tough to know these. You didn't write it correctly. You can't like go to everybody and say, "No, you're wrong. I meant this. Look at page 92." The reader is paramount. Like I always say there's a partnership between writer and reader. But the fact of the matter is the reader is 100% in charge. So if you have not made yourself clear to them, that's your fault as the writer. There's a corollary to that, which is also readers bring a huge imagination. Every person has their own imagination and that you can overwrite. But usually, the reader's imagination can fill in what you need them to fill in. So when I started working on Three Muses, which, as you said, has a ballet protagonist, I was making the ballet Swan Lake the center of the book. I woke up after a few years after watching 10,000 videos of it. First, I said, I'll never know this as well as anybody else knows it. Second of all, it has literally nothing to do with my book. As a writer, it's not in service of the plot. So I ditched it and I opted for making up all my own ballets. Readers have said to me, so I chose the music and the costumes and the steps. Readers have said, "How did you do that?" The interesting thing is I didn't really do it. The reader did it. Because for each ballet, there's almost, I think every ballet is less than three pages, sometimes less than two pages of description with what the costumes look like, what the sets look like, a description of the music. So it's not choreographed at all. It's a page to stimulate the reader's mind to picture what they're seeing. It's a really interesting psychological insight that the readers will fill that in.

DN: Yeah. We have a question for you from past Between the Covers guest, Jai Chakrabarti. We spoke about his remarkable story collection, A Small Sacrifice for an Enormous Happiness, of which The New Yorker said, "The stories in this collection, set variously in America and India, are propelled by familial anxieties. Chakrabarti’s characters—diverse in race, class, sexuality, and religion—reveal themselves through longings. These tales eschew neat conclusions, leaving their protagonists suspended, as one opines of life itself, 'between unbearable truths—salvation or suffering.'" One of the ways we looked at his collection was through the lens of a poem by Robert Bly called The Third Body, a poem where a couple has found a deep harmony with age, an unspoken contentment where Bly says, "Their breaths together feed someone whom we do not know." Also, "They obey a third body that they share in common. They have made a promise to love that body." I think you evoke a third body in this book in multiple ways, but certainly music is a third body for Victor and Adele. Here's a question for you from Jai Chakrabarti.

Jai Chakrabarti: Hi, Martha. It's such a pleasure to be in conversation with you and with David. One of the things that struck me while reading Duet for One was the novel's deep attention to what isn't said, the silence, restraint, the pauses between beats and words. In a book so immersed in grief, longing, memory, there's a kind of emotional undercurrent that often moves just beneath the surface. So it made me wonder how you think about the unsaid in fiction, how silence and ambiguity can carry meaning. Given your background as a classical musician, do you see any parallels between writing fiction and performing music, not just in rhythm or tone, but in the way both forms evoke feeling without necessarily naming it? Thank you.

MAT: David, thank you so much. I really love Jai Chakrabarti's writing. I think that question is so beautiful. I want to put it on my wall and look at it. [laughter] He's a beautiful reader.

DN: He has such a great voice.

MAT: He has a beautiful voice. He's also just a beautiful interpreter of the written word. Like sometimes I just want to just, could you just talk to me? So this is a really complicated question. Another thing that I learned from Max Aronoff, and honestly, I think every rock musician knows this, is that the music is in the rests. So if you are not familiar with classical music, a rest is really a time of silence. There are rhythms associated with it. The rests have a certain amount of time, depending on what the composer says and how long that silence goes, etc. So I think that's like an incredibly important concept in life. It's really important in writing. So to go back to early criticism that I got from a really good friend who actually said, "You write like a lawyer, you're pounding your point too many times," that's where silence comes in. A lot of my late, late stage editing and also editing that I do on other people's work is taking off the last sentence of the paragraph, the last two sentences of the paragraph, because I noticed that your instinct as a speaker, so I think it's an instinct as a writer, is to make a conclusion. It's the reader that has to make the conclusions. So this question about ambiguity and silence is, for me, paramount on a number of levels. I can really just speak for my life, but I think it has been part of my maturation to understand that everything in life is ambiguous. There are no answers. Nothing is set. Everything is in flux. That's really great against my personality. I mean, I definitely have aspects of being a control freak. It really doesn't work in fiction. Ambiguity is your friend in fiction. Too much is confusing to readers because then they get lost and that's not fun. But ambiguity is the stuff of human life. Even with our closest friends and relatives, partners, whatever, speech is imperfect. We can have misunderstandings all the time. We cannot understand. Every human is individual. So ambiguity is really the stuff of life. I think it's the stuff of fiction, partly because I [inaudible] misunderstanding in fiction. That's part of what I do. I think we constantly misunderstand each other, misinterpret each other. The humans are curious species, but we don't always know what we're looking at. Actually, I wrote a piece really early on. I was lucky enough to go to Morocco in 2014, and a colleague of mine said, "Oh, oh, I just got back. We did great. We're doing all this feminist training there, and yay, we're bringing our Western ideas about women's apparel," and blah blah blah. I was in a small town in the mountains and just stood one morning and watched women walking down the mountain with blankets full of laundry to go to the communal washing place. They had to bring that back up the hill, and I'm assuming wet. The first thing I thought was, "What the hell is anybody doing in this country trying to teach feminists whatever when you have to walk down the mountain to do your laundry?" It just felt so disjointed. But the thing that I realized, what I said in this piece that I wrote is, "I know what I'm seeing, but I don't know what I'm looking at." That's really what I felt. I have a completely Western eye. I grew up in the United States. I don't know what I'm seeing. I don't know if this is cruelty more than coffee clutch for the women doing their laundry. Maybe it's a way to get away from home. I really cannot. I can't tell you what I was looking at. So that's how I feel about many things. I try to exploit that in my fiction. So as to Jai's question about whether performing and writing, I see a similarity, it's kind of unromantic, but not too much. I see a huge similarity between practicing and writing. I think writing begets writing. I think it's like anything else. You have to do your 10,000 hours. So I'm big on the fact that there's not that much inspiration in writing. It's like, put your tush in the chair and just do the work. So in that sense, I see a huge connection between practicing and writing. I have, since my first book came out, done an enormous amount of public speaking. That's where I think performance makes a big difference. It's very comfortable for me. It's so much easier for me than performing solo. It's actually pretty relaxing. I'm totally enjoying talking to you. I'm often in front of a crowd. I think that musical training, but that's not an esoteric concept. It's because I spent a lot of my life performing. So I wish it were more interesting, but I'm not sure it is. [laughter]

DN: Well, unsurprisingly, we have another music question for you. This one about music, not so much within the book, but outside of it. This is a question from the writer, Lydia Kiesling. Her most recent book, the best-selling and critically acclaimed novel Mobility, was described by Namwali Serpell as a deeply engrossing, politically astute tale of the intricacies and intimacies of our daily complicity with late capital, with the collective bargain we've all made to count calories and coins while the world burns. So here's a question for you from Lydia.

Lydia Kiesling: Hi, Martha. This is Lydia Kiesling. I love the way your books incorporate music, both as part of the story and sometimes even in the form itself. Can you tell us about how music figures in your writing practice and your life? Thank you.

MAT: Thank you so much. So I literally just finished Lydia Kiesling's Mobility last week. I hadn't gotten to read it. So I just want to say it's a really, really interesting project, that book. It's really hard to write a political novel and make it also readable and interesting and rich. I suppose it's a really exciting, exciting project. So Lydia, if you listen to this, I'm sorry it took so long. [laughter] Yes, the answer is I'm obsessed about the sound of language. It's incredibly important in my writing practice. I am told by my family I'm often talking to myself when the door is closed, reading stuff out loud. But I also hear it in my head. I have really strong opinions about what sounds right. Sometimes I'm a fast writer, but I'm a really, really slow reviser. The opening scene of Duet for One, I probably rewrote 2000 times. I don't think that's an exaggeration. I just couldn't get it right. So another thing that is related to me, because the sound of language is important—I would say this: I take a poetry class every two years, and I'm definitely not a poet, but I wish I were, because I hold them to higher esteem, because that attention to words and sound is so beautiful in poetry. I'm also really, really really really not a visual person, but I have visual impressions of what I'm writing. So I'm very aware of fat paragraphs and skinny paragraphs and whether the building blocks are in the right place. And for whatever reason, I have trusted my judgment on that. If something feels like it's going to topple over or it's imbalanced, I have to revise it. And that's just really interesting to me to have this internal architect, whereas I couldn't tell you what pictures are on the wall of my house. There's a lot of mystery to writing.

DN: I think so too. Even if the duet between Victor and Adele is the most obvious duet, that then becomes a duet for one in your novel, I think there are many duets. Their son, Adam, even when his mother is alive, as you've already said, feels alone, neglected, perhaps overshadowed, certainly not mothered in the way that he craves. Her career is first and foremost. But what is tough is that part of her career is being always available to her students, never overbearing, always a willing ear. Thus, she's beloved for these qualities, qualities that Adam himself never receives. When she dies, you say or you write, "Adam didn't feel sad and mournful, more like he had a rash that itched all over." He seems caught to me in a sort of arrested emotional development, trying helplessly to differentiate himself by becoming not a pianist but an accomplished violinist. Yet even after his mother's death, there seems to be a limit, as you've also mentioned, to the intimacies he's able to establish outside of music. This seems like a good time to introduce the other major character in the book, Dara, who represents another duet that comes and also comes undone. Introduce us to her as we first discover her in Duet for One.

MAT: Thank you. So Dara is a young violist and she is studying with Isaac Koroff, who's the viola teacher, who's modeled on Max Aronoff, my own teacher. She doesn't come from a musical family, unlike Adam. She's very, very diligent and she's extremely interested in music. But for Adam, music's in the water supply. So they meet because they play in the same student orchestra, and then they spend some time together at a summer music program. They fall in love with each other. Dara feels—I was going to say rightly or wrongly. It's kind of both rightly and wrongly. She's very, very intimidated by Adam's parents. So on the one level, she's right. She's not conversing at all with the lifestyle thing. She doesn't know musicians. She doesn't really understand what this world is. But also, she is insecure about her own playing. So she might make this worse than it actually is. They're very young. They're in their early 20s. So Adam feels this breath of fresh air. We can't really articulate it. But he likes the fact that she's not in conservatory. She's going to college. She's studying all this stuff that he's never going to get to study because he's in a music conservatory. Dara leaves him precipitously for various things that come to pass in the book. She also has to leave music. She ultimately becomes a professor at Penn. Adam finds himself thinking about Dara, not quite on the first page, but on the third page of the book. His mother's death brings something up for him about her that he hasn't resolved.

DN: Well, even though Dara isn't you, there are some rough correspondences with your own life. Unlike your pursuit of ballet as a child, where you say, "Sadly, my passion did nothing to make my arch bigger, my extension higher, my back straighter, or my body more flexible. It was clear by age 10 that I lacked any of the prerequisites for a professional ballerina. When my classmates were invited to audition for the children’s parts in The Nutcracker, I was not considered, not even for running around in a large mouse head. Finally, the ballet school refused to advance me." [laughter] Unlike this, you had great promises as a musician. You majored in music in college. You were the first chair violist in the orchestra. You thought at the time you would become a professional viola player, training through your early 20s. This is true of Dara as well. Like Dara, you were encouraged by an esteemed teacher that you both loved to go to music conservatory. But both of you had enough other interests outside of music that you wanted to go to university and to study more broadly while also continuing a rigorous musical practice, meaning you had a full course load. On top of that, were practicing viola hours each day. Both of you also have an experience with a new teacher when you go to university that derails you from your professional musical path, something that I do want to talk about a little later. Both of you end up centering words in your future careers, even as you did continue to be active in the amateur chamber music scene in Boston during law school, playing with musicians from MIT's math department. For years afterwards, as a lawyer, you were in a semi-professional orchestra in Washington, D.C. But let's spend a moment with your beloved teacher, the esteemed violist, Max Aronoff, who you've dedicated the book to, and who, unlike Lilian Kallir, who isn't an influence on the book beyond this surface-level connection, your experience of Aronoff is a direct influence on your portrayal of Dara's education as a musician. In looking into Max Aronoff a little bit, I found a remembrance of him by the violist Toby Appel, where he says, "He used his own bowing exercises, which were like calisthenics. Instead of moving your entire arm, you move just your fingers and wrist alternately. We would go over these exercises as if he was practicing with me, correcting every step. His advice was that if you play something right 99 times at home and screw up in front of the audience, that's the one that they hear, so you had better practice more than 99 times." I also found this quote from Aronoff himself, "String playing is pure craftsmanship. There are no shortcuts. One half hour a day does not mean anything. It does as much good as a hat rack at a synagogue." [laughter]

MAT: I've never heard that one. [laughter]

DN: So thinking of you describing your being booted out of ballet, and then the humiliation you felt later from a future teacher that derailed your professional aspirations as a violist, I imagine both of these experiences on their own must have informed or influenced your perseverance and perhaps ultimately your success in writing. But I also wonder if Aronoff's approach to technique and discipline and the focus being on the hours, as you've already mentioned, are a huge part of that as well. But I just wanted to spend another moment. You've already done this multiple times today, but is there anything else pedagogically or otherwise, personality around studying under Max that you would connect to your writing practice or to other aspects of Duet for One or the teacher that you evoke as a fictional character in Duet for One?

MAT: Kind of everything. I feel like other than my parents, Max taught me everything that I know. There used to be a sign about kindergartners, "Everything I know I learned in kindergarten," about learning to share, play in the sandbox, be nice to each other, which we could all use some right now. But anyway, so two things I want to say about the Toby Appel comment. I have a lot of teachers, and unlike any other teacher that I've ever studied with—I also studied piano—you had to do this at home. But then when you came in, he watched you go through these machinations—I put it in the book—of these incredibly rote, repetitive exercises that were strengthening for both hands. You couldn't get away with it. He stood there with a sharp pencil, and you had to play it for him, if it took however long it took. So that was, in my experience, unique. I don't know how many other teachers do it. But I think the biggest thing he taught me is the necessity of breaking music into incremental pieces. I'm married to an environmental activist, and he has an expression: "How do you eat an elephant?" The answer is one bite at a time. [laughter] I think it's a similar concept. You have to reverse engineer what you're doing and break things down into incremental pieces. Because if you look at the whole, it's impossible. Like, "Oh, I think I'll write a novel." It's absolutely paralyzing. In law school, my first year of law school, we had one exam for the entire year. Your total grade was based on that one exam. "How am I going to study for this?" Well, I felt very, very, very well prepared to study. I just knew how to break things up, start early, go over a million times. It's not that I'm so smart. It's just that I have the tools for that. The same thing with almost any work setting that I've ever been in. If you think of the project as a whole, it can be very, very paralyzing and frightening. So my writing advice to anybody, but especially new writers, is don't worry about the whole. For myself, if I can finish for the day with one sentence possible for the next day, I'm like, "That's good enough." I just need to be able to write a sentence because that will beget things, but it's a trust. It's going to be slow, and it's going to have a lot of component parts. So to me, that's just the most incredibly life-changing lesson. I feel so lucky to have had a mentor like that.

DN: I want to suggest a connection, and I wonder if it's a forced connection or not. So I want to hear your thoughts on it. But when I hear you describe your instrument, the viola, I want to draw correspondences between what its role is in music and the way you approach writing. You described the viola, that it isn't a solo instrument. Of course, I'm thinking here again of this theme of Duet for One also, and duets, that the viola isn't a solo instrument, that it's always part of an ensemble, that it is an inner voice that listens for and plays off other instruments within the group, which also makes me think of Bly's third body, this interstitial connective force. You've also described it by saying, "Think alto in the choir, the middle voice that buttresses—and often creates—harmony. The instrument that must attune to melody and bass." I wonder about this inner voice that listens for and plays off others in a group, what this says about you, and how you approach story or story writing. I could imagine a lot of things. For instance, I could connect it to you saying that you're more interested in the musicality of words than plot, and often mentioning Shirley Hazzard as a writer you love because of this. That perhaps this listening for a voice in between as a violist might relate to developing the skill to listen for a musicality of syntax in writing. I have no idea. But I'd love to hear your thoughts about a violist sensibility as a writer—if that is actually part of your sensibility as a writer—of being positioned in what feels like a very specific thing for an instrument to be this in an ensemble, that you never have your solo, but you can't imagine the ensemble without the viola either.

MAT: It can't work. It can't work without a violist. Yeah. So I absolutely love this question. So there's a simple way to answer it, a more complicated way to answer it. This never occurred to me until I was in Berkeley for an interview for Three Muses. I was interviewed by a very close friend of mine, Gwendolyn Mok, who's a professional pianist. She'd never done a book interview before. She said to me, "I've read your book twice, and I just realized you write like a violist. This is a viola novel." This is Three Muses. I shouldn't even read Duet for One. I can't articulate it very well. You articulated it beautifully. I never thought about it. She's like, "You're inside this thing. There's a way that you're inside the action and describing it from multiple angles that feels like a viola player." So I was not aware of this, but I can speak a lot about what it's like to play in a string quartet. The miracle of a string quartet, if you ever see one, is that there's tremendous communication. There's no conductor. People have to adjust to each other, both in terms of pitch and tonality, but also rhythm, also phrasing. I mean, there are rehearsals, you work this stuff out in rehearsal, obviously, but there's a tremendous amount of unsaid communication. The viola is—it's true for orchestra playing as well. It's what you said, sometimes the viola is paired with the melody, the violins. Sometimes the viola is paired with the cello. So I'm sorry, I want to clarify. A string quartet is two violins, a viola, and a cello. The cello provides often the rhythm and the bass line. But if you heard a string quartet or an orchestra without violas, you would really feel like something was off. It would be boring. You wouldn't have a texture. Definitely in an orchestra, you've got to be listening to all sides of the spectrum. I mean, very big concert halls, this can be a problem because I often felt like the viola is too far away from the first violins. There's a sound delay. It's hard to match your sound. When I was growing up, the violas were seated physically in an orchestra inside with the cellos on the outside. I've noticed that most orchestras now put the violas on the outside, which I don't know what I think about that, but you're even farther from the violins if you're doing that. So it's complicated. You're always next to the cello, so you can adapt. You can adjust to them. But there's a tremendous amount of adjusting that goes on. I always want to distinguish this from playing electric bass or guitar or acoustic guitar because those instruments have frets where you can put your fingers. It's a guideline where the pitch is, but the classical stringed instruments have no frets. So do you remember reinforcements, those little sticky white things that you put around the holes, like younger readers might not know what these are, but the early days you would see the very beginning elementary school students sticking reinforcements on their fingerboards so they'd know where the pitch was. It just doesn't work. [laughs] You have a hot day or a cold day or a rainy day, your pitch is out immediately, and string instruments go out of pitch all the time. So when you're performing, you have to adapt to that. So I guess there's some connection, but I couldn't say it the way you said it. It's kind of instinctive.

DN: Well, both of your books are a blend, I think, of imagination, research, but also drawing upon your own lived experience. What's interesting in your talking about them is the ways reality is sometimes a facilitator of the imaginative in your narratives. For instance, Max Aronoff being an uncomplicated influence on his avatar in Duet for One, but also how sometimes reality is a hindrance or obstacle to finding a true rendering of what you want on the page. I mean, the most obvious thing we could think of as an example is what you've already mentioned, that after four or five revisions of having the ballerina Katya perform ballets that actually exist, where you'd super researched Swan Lake, watched innumerable performances of it for research, that it's throwing out Swan Lake and creating your imaginary dance that freed up the fiction. Yes, choreographing your own ballet starting from scratch and building up a ballet up from the beginning through Katya's rehearsal process, breaking the pieces down into their component parts, I'm sure created all sorts of other challenges. But it lived more fully on the page than trying to capture a ballet that actually exists. You've similarly mentioned Bellevue Hospital in Three Muses. You got caught in trying to learn the period details of the interior of the actual building in the 1940s, something you were liberated from by making the hospital fictional. In Duet for One, as we've already discussed, you used the real detail of Lilian Kallir but breathed life into that detail almost entirely via the imagination. I also think of the more mysterious connections between the real and the imagined. You've mentioned this also today, how when your mother died suddenly when you were in your 40s, it was her death that unleashed your writing life, where from then onwards, you really committed to it and stuck with a commitment. But you've also mentioned much later when your dad died, "It came in a sudden gust, the thought that I could give it all up, throw everything overboard, ditch the career in social justice that I truly loved and that was close to forty years in the making, and do what had been calling me for decades: write full time." Surely, whether consciously or unconsciously, the loss of your parents, I would imagine, informed or influenced the rendering of the death of Adam's mother, Adele, in your novel. But I'd love to hear more generally about navigating research, imagination, and lived experience. If you have a method, or whether it's instinctual or trial by error for any given instance, when one is a fuel or a foe to successfully writing what you want to write.

MAT: I'm a lawyer. I work professionally. My professional life is all research. To be really frank, I can't stand researching for fiction. Sometimes you have to. You have to. But it isn't why I write fiction. So I research on an as-needed basis. Like you said, I found that jettisoning certain historical facts was liberating because I didn't really want to be figuring out the linoleum tiles in Bellevue Hospital in 1955. It's like, "Really, no interest in that." So I guess another thing that's going to sound really weird, I didn't know that I wrote a historical novel or two historical novels until somebody told me. I don't think of myself as writing a historical novel, but you're writing in the past. So, in terms of my own parents' deaths, there are a couple of things. I think I mentioned earlier that my father's mother became almost deaf at his birth. He had a really distinctive style of speech. It's what gets on the page of my first draft. It sounds a little bit archaic. It took a couple of early rejections where people talked about that, that the language was very stilted, or he wasn't a stilted speaker, but he had a very fluid, elegant speaking voice and used words that people don't use, especially not in the 21st century. So apparently that's what I hear. So that's really interesting. That's just his voice and it gets on the page, and I have to go back and not take it out but streamline it. And it's a harsh reality, but after our parents die, we are—I don't like to say liberated. Some people have terrible relationships with their parents. I didn't, fortunately. I had great parents. But since it's such a tectonic shift in your life and in the family construction and the family of origin, there is something loosening up, liberating about it. So I really try really hard not to analyze what I'm doing, like, "Where did that come from?" and "Where was it in my imagination?" But I need to say that I'm just starting to send out—I'm looking for an agent for my third novel, it's really surreal. I find that really interesting, whereas it's still going to be considered a historical novel, but it's essentially, one aspect of it is about an eight-year-old girl who gets stuck in a John Singer Sargent painting. So it starts with The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, which is a painting of four girls in the same family. The eight-year-old girl in the painting gets stuck. You know, I'll say that to people, and they're like, "What? How does a girl get stuck in a painting?" I'm like, "Well, that's my job as a novelist. You're going to have to try to convince you of that." I don't have any clue where that came from. I mean, that stuff has to be imaginative, right? I mean, so I don't totally understand my own process and I've been very loath to interrogate it.

DN: That sounds smart to me.

MAT: It's funny. I've listened to a lot of your interviews and writers on your show are sometimes really expert at describing their processes, but I'm afraid to get near it because I'm afraid to disrupt my flow.

DN: Yeah. No, I think I would be the same as you.

MAT: Interesting.

DN: Yeah. Well, one thing the fictional Dara and the real you share that was pivotal in both of your lives is a horrible experience with a music teacher, an experience that was about power and gender. In your real life, you've talked about how working in a corporate law firm in Philly, you were warned never to enter the chairman's office alone as he was known for assaulting women, and how your immediate supervisor was loud, offensive, and would call you to see what you were wearing. In the fictional of the three muses, the narrative involves a power dynamic as well as grooming and exploitation. In the real world, you describe how in college you were, in your words, shredded by a new music teacher and devastated because of it, causing you, despite your full course load, to increase your practicing from three hours a day to six hours a day, but also how you kept the experience a secret from your musician friends out of shame. Perhaps my favorite conversation you've had about this book is on Leah Roseman's show, Conversations with Musicians, where you talk about how this teacher had a reputation of doing this, and this reputation of doing this was particularly two female students of his, and how it took you many years to be able to write about people as you do in Duet for One, pursuing a musical education without it being entirely negative. Dara in this book has inherited the silence and the shame that you felt. In fact, her silence and shame, her inability to speak to it or about it with her musical peers or with her partner Adam changes her destiny and Adam's destiny both. When you were in conversation with the former classical music critic for the Washington Post, Anne Midgette, she acknowledges both the history of abuse like this in the industry, but also your restraint in portraying the abuse. I think, for instance, of how the Caldwell Institute of Music in Duet for One is modeled after the real-life Curtis Institute, which itself has recently been embroiled in a reckoning due to the courage of the violinist Lara St. John, speaking about how when she was a first-year student, her 78-year-old violin teacher touched her inappropriately, something that eventually progressed to rape. That this teacher made suggestions at the time that she might be forced to leave if his advances were rejected. St. John had reported the assaults repeatedly to the music school at the time and was ignored by the school. Instead, her and other classmates were mocked and disregarded for their reports. But in 2019, there was a Solidarity concert in New York for all female musicians who suffered sexual abuse in the classical music industry. During it, St. John shared a collection of over 400 personal emails she had received since going public, including the account of an eight-year-old music student who ultimately committed suicide. These accounts read to the audience of assaults from across the music world, Curtis, but also Juilliard, the Cleveland Institute of Music. Reading all of this, just out of my own curiosity and preparing for today, I agree with Anne that given the actual world of music education, you write this in a reserved way with a light touch, with most of it off the page, but a humiliation that becomes an atmosphere rather than a focus that has stayed with and dramatized. Thinking about this question of when to imagine, when to render the world as we know it, when to use research, when to allow the reader to infer. I guess talk to us a little bit about this element of the book and how you navigated it, which appears to be something quite common in the world of music education. Of course, really of any place that has a deeply entrenched power system. Like when I talked to Vajra Chandrasekera, we were talking about this in Buddhism, for instance.

MAT: Oh, that's so interesting. It's so disappointing. It's everywhere. We live in a patriarchy.

DN: Yeah.

MAT: The teacher, Lily's teacher, also was modeled on a real-life Juilliard teacher who didn't like Asian students. She used to throw books at them. Literally, they'd be in their piano lessons and she'd throw books at them. Anyway, so there's a lot of abuse. So I probably said this to Anne Midgette at the time. I really didn't want this to be a book about abuse. Personally speaking, I've been extremely fortunate as a female growing up in the 20th and 21st century not to have experienced extreme abuse and no physical assaults, which is a miracle. It's incredibly common, much more common than we know. I feel really, really, really lucky. I usually say what I want to write about is love and death. But I'm really, really, really interested in grief and how, in America, at least, we have no capacity to talk about it, to help our friends and neighbors. I think we're all suffering from extraordinary grief and trauma from the amount of violence in our society. So I'm much more focused on the grief aspect and the love aspect. If I may, in Three Muses, as you mentioned, the power dynamic is grooming and that is a completely abusive relationship. I didn't censor myself. That part of the book is focused in the 1950s, and it's so common. I didn't think about it. I really wanted it to be real. I mean, I thought about it. I'm sorry. But I didn't think about censoring it. It was real, and I really, really wanted to make that real. It wasn't until we got to the jacket copy that I realized I better say something because people may want a trigger warning. So we put on the jacket copy that this was an abusive relationship. But in Duet for One, I really didn't want to focus on that.

DN: Well, it seems like a good time to ask you about social justice and your work as a lawyer. I asked poet and former lawyer Monica Youn about this a little when she was on the show. She has talked about the ways she sees a relationship between law and poetry, about how metaphor is analogical reasoning, and that is also what the law is. That something like the Citizens United decision is built on three metaphors: Money is speech. Corporations are people. Elections are marketplaces going to the highest bidder.

MAT: God, that's so brilliant. That's great. That is brilliant. [laughter]

DN: When you're asked about this, you often say, as if it were an obvious connection, that you became a lawyer because of a love of words, which I want to press on because it's not an entirely satisfying answer for me yet. Because there are a million jobs you could say this about, not just language-centric jobs like an English teacher or a librarian or a philologist, but also any number of disparate professions from a singer to an auctioneer to the host of Wheel of Fortune to a politician to someone working in AI to decipher whale languages. So what legacy, if any, of law and the pursuit of social justice, which you very explicitly were centering in the work that you did in your philanthropy, how does it find its way or the experience of doing it find its way in the way you engage with words?

MAT: I used to say these worlds were totally separate, but of course, I'm the same person. So that can't actually be true. My third book is explicitly dealing with racial justice issues. I was deeply steeped in that and got an incredible education professionally, but also sought one out personally in what our real history is in the United States, which is why we have book banning and why we have an administration that doesn't want to teach history and wants to eradicate education. This is not a pretty history. It's also the reason we keep going through these horrific cycles of violence and prejudice. Three Muses deals with the Holocaust. When I speak about that book, I talk about multiple Holocausts. Unfortunately, it's not a single event and hate is really, really, really dangerous, and human beings are capable of tremendous hate. So in that sense, I think there is a very strong connection. One of the things that I have decades and decades ago, I mean, I read a lot and I made a promise to myself that for every book I read by a white writer, I would read a book by a writer of color. I mean, I don't even think about it anymore. I just do it. But I think a lot of white people in this country tend to write white authors. I don't want to be didactic about this. I think it's an incredible loss. You're really losing out if you're not reading books by writers of color. I mean, I'm sorry for you, basically. It's this gigantic literary heritage that we have in the United States. When I reviewed Kiese’s book Heavy, I was like, "This guy is like the first rate man of letters. Go forth and read it." But I still call it a Black writer. When Trump fired Kevin Young at the African American History Museum, I was like, "God damn, firing Shakespeare." I mean, how do you feel about this? He just fired Shakespeare from his job. You know, he's an incredible American asset. Anyway, I don't think you're asking me this. But I haven't felt an explicit connection. But one of the lessons that I learned in social justice that was really, really, really, really powerful is the power of love and the legacy that is such a huge gift, if we could see it, of radical Black love and radical queer love. It's like, if we could follow the tenets of what that means and what inclusiveness really means and what radical love means, it's not like ditzy Hallmark cards, and what it really means to love each other, we would be in a lot better shape than we are now. So that's one aspect of love that I'm really interested in. I do feel, I hope, that it permeates my fiction. Just a little teaser, because I don't have a publisher or an agent for my next book. But the other half of my book, in addition to the girl stuck in the painting, is about John Singer Sargent's Black model, with whom he had a long relationship. I don't like that word because it's surely exploitative. But that model, Thomas Eugene McKeller, is the second protagonist in my book. He was literally whitewashed from history. He is the model for every white figure, whether all white—the men and the women—on the Rotunda of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. So it's an incredible metaphor. It's literally a whitewashing. If I ever get lucky enough to publish that novel, that feels like it's bringing together a lot of my work in this area. P.S., while I have a platform, [laughter] I think this whole concept—I mean, we're seeing it's just writ large playing out with DEI. It's like, this isn't DEI. This is our goddamn history. We live in this country. If you didn't come in chains or you're not Indigenous, you emigrated here and you should know your own history. I'm going to get off my soapbox. [laughter]

DN: I'm glad you got on the soapbox. Well, this is a perfect segue for the next question. In light of your first book, which you've already mentioned, deals with the legacy of the Holocaust, among other things, you've given talks about how to write collective trauma. Duet for One, in contrast, deals more with interpersonal and individual trauma rather than questions of peoplehood, which will make me curious to hear your answer to this next question in relation to the book we're discussing. This is from the writer Miriam Gershow, whose most recent novel, Closer, is just out this spring. Mary Rechner says the following about it: “Miriam Gershow’s propulsive novel, Closer, is a fearless tour-de-force of imagination and empathy. Racist bullying of interracial high school sweethearts in a liberal, majority-white university town opens the story. Gershow’s quicksilver shifts in points of view deepen it, illustrating how we yearn to be seen for who we want ourselves to be, while carelessly using the markers of race, class, education, and ability to marginalize and minimize others. Serious stuff, but one of Gershow’s many gifts is writing funny, making us love the relatable characters in Closer even when they flip-flop between perceptive and clued-out, and barrel toward tragedy.” Here’s a question for you from Miriam.

Miriam Gershow: Hi, David and Martha. David, thank you so much for asking me to be a part of this conversation. Martha, I'm so happy to be here on behalf of Duet for One. I think you know that I love this book, and I've also loved having you as a fellow Regal House author, you with your second book and me with my third. It’s just been great to get your wisdom and experience on this crazy publishing journey. One of the things that I know we have in common is that we are both Jewish authors, but we don’t always have a lot of explicit Jewish content in our work. When I was reading my last book, Survival Tips, to the synagogue sisterhood, one of the women in the sisterhood who knows me in town said to me, “How are your books Jewish?” I answered kind of defensively about, “Oh well, all my characters aren't Jewish and I am not a religious practicing Jew so I don’t center Judaism in my work.” She said, “No, I wasn’t asking about the subject matter. I wasn’t asking about the characters. I was asking, how does you being Jewish—your sensibilities, your lived experience, your humor, your voice—how does that infuse your work?” That question struck me as such a different question and so generous and something for me to really ponder. I have been pondering it ever since. So I'm going to ask you the same question. How is Duet for One Jewish?

MAT: First of all, thank you so much, Miriam. Because Miriam and my book came out at the same time, I haven't really gotten to delve into her work. I'm so glad she's here and I can't wait to read it. So this is a really complicated question for me because I am Jewish on both sides. Both parents were Jewish, but I don’t think it was possible to grow up in a more secular household than I grew up in. My dad’s extended family actually feels much more culturally Jewish than my mother’s, which really had nothing to do with the religion, period. Christmas, Easter, they were really not into it. But to give you an example of just how secular the extended family is, I’m one of 15 cousins, and there was no bar mitzvah or bat mitzvah of anyone in my generation. I came of age with a lot of regret about this. I felt it was a huge hole. I felt unrooted. I think Judaism is an ancient religion with enormous, valuable history. We are people of the book. I've basically, since my very early teens, been trying to educate myself. I wouldn't say it’s a religious education at all, but I’ve read a lot of history. I read a lot of Jewish writers. Yet, I'm never going to be one of these authors who only writes about Jewish subjects. The benefit of growing up in a really secular household is that everybody came through the door. None of my parents’ friends were Jewish, none, despite the fact that we lived in suburban Philadelphia. There were a lot of people from other countries. I mean, we had a very broad exposure. So I'm never the right person to ask about this because I always worry when answering this question that it sounds chauvinistic and it's very fraught nowadays. But I think the basic tenets of Judaism are truly about justice. We don’t have a concept of an afterlife. So it’s about doing what you can in this life. I feel that personally for my own professional life. I felt incredibly lucky to be able to do this work. I try to carry it on in other ways. Particularly, I have a weekly Substack. It’s clear to me that people need support during this time and resources. So I’ve turned half of my Substack over to that, even though I never intended to do that. But I feel we have a duty—like many Jewish people feel—to heal the world and to bring justice to the world. It’s something I admire tremendously, tremendously, particularly about Jewish life in America. I can’t prove this, but disproportionately, I find probably defenders—white people who work in social justice—are disproportionately Jewish. Classical music is like a thing. [laughter] I mean, it’s not only Jewish people. There are other cultures that require kids to learn instruments. But classical music is deeply part of Jewish culture. I didn’t understand this until I was a full-grown adult, that dozens and dozens of musicians that I had interaction with or that I heard perform by growing up or that influenced my musical education were Holocaust refugees. I didn’t understand that. I mean, they had accents. I can’t even reconstruct this fully, but I know I played chamber music with an Italian Jewish man in Philadelphia as a teenager. I can’t remember his name, but I just remember seeing, what, he’s Italian? But then I looked around the house, it was clear he was Jewish. I didn’t know there was such a thing. I mean, I had a tremendous amount of contact. I just didn’t know that’s what I was experiencing. I also feel that we are people of the book. One of my favorite books on this subject is written by the great Israeli novelist Amos Oz. His daughter’s name is Fania Oz-Salzberger. She and her father wrote a book called Jews and Words. It opened my mind. It’s very readable. It’s not a scholarly text. Basically, to the importance of argument and questioning authority, which I think is extremely Jewish. I don’t think it’s an accident that most of the communists and socialists in this country were Jewish. Jews were very, very drawn to that because we don’t have a dictatorial God. We are encouraged—again, I learned this, this was very explicit in that book. We are encouraged to question the teacher. Moses questioned God and he did it constantly. God expects to be questioned. Also there's an expression, "two Jews, three opinions." We don't agree on anything. So Duet for One is not in the slightest bit a Jewish novel, in my opinion, but it's probably not an accident that Victor is the son of Viennese immigrants. It's a very minor part of the story, but he's married to a mainline debutante-type person. I don't think it's an accident either that in Three Muses, the protagonist John is Jewish, and the ballerina that he falls in love with is Catholic. I grew up in a very Christianized household and I only went to public school, but I'm just telling you, Christian culture is what's dominant in this country. If you get a public education, you are learning European history, you're learning Christian culture. So I guess the cultural values in Duet for One and the intellectual values and the questioning that Adam has to go to, I guess, make it a Jewish book. Certainly the musician Isaac Koroff, to me, is a very Jewish character. He has that sense of humor, that wry sense of humor that's associated with Jewish people. I think it's hard for a Jewish person to describe this because it's so in our veins that we don't even know what we're talking about. So that's the best I can do. Somebody else might have a better answer. [laughs]