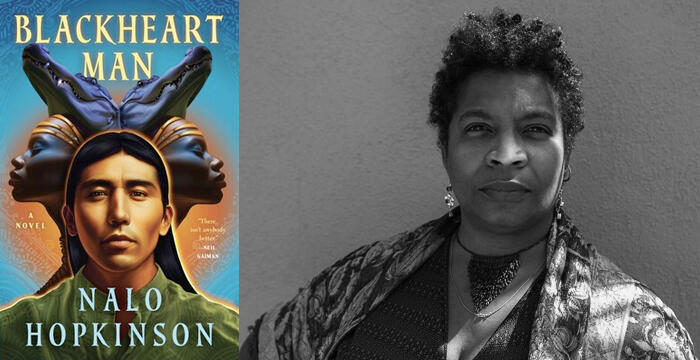

Nalo Hopkinson : Blackheart Man

Todays’ guest is Grand Master of science fiction and fantasy Nalo Hopkinson. Together we center her first novel in over a decade, the remarkable Blackheart Man, and look at what it means to not only write an alternate Caribbean history, but within that history conjure an entirely new culture, one with its own language, sexual norms, family and gender dynamics, and racial politics. And yet a culture that remains, for all its invented differences, deeply Caribbean. Blackheart Man is a book exploring the “what-ifs” in the histories of marronage (autonomous fugitive communities of escaped enslaved peoples) and of what can be recovered from the ruptures and erasures in the archive. Nalo’s latest novel becomes the lens through which we explore everything from the use of vernacular speech in one’s work to the reckonings around race that have rocked the SFF community in recent years.

Nalo’s appearance on the show joins many archival conversations with touchstone writers of SFF today, from Nnedi Okorafor and N.K. Jemisin to Ted Chiang and Kelly Link, from Kim Stanley Robinson and Jeff Vandermeer, to William Gibson, China Miéville and Ursula K. Le Guin. I’ve created a “Legends of Sci-Fi and Fantasy” playlist on the show’s YouTube channel so they are easily found in one place but you can also sort for “SFF” at the show’s home page as well.

If you enjoyed today’s conversation, consider joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. There are an incredible number of rewards and gifts to choose from when you do. You can check it all out at the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today’s episode.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode of Between the Covers is brought to you by All Lit Up, Canada's independent online bookstore and literary space for readers of emerging, quirky, and acclaimed indie books. All Lit Up is your Canadian connection for award-winning fiction and poetry, author interviews, book roundups, recommendations, and more. The only online retailer dedicated to Canadian literature, All Lit Up features books from 60 literary publishers and now they offer e-books in accessible formats through their ebooks for Everyone collection. All Lit Up makes it easy to discover and buy exciting contemporary Canadian literature all in one place. Check out www.alllitup.ca. US readers can also shop All Lit Up close to home and save on shipping when they purchase books from its Bookshop.org affiliate shop. Browse selected titles at bookshop.org/shop/alllitup. Today's episode is also brought to you by Misinterpretation; a ruminative and propulsive novel by Albanian American fiction writer Ledia Xhoga. Heralded as absolutely gorgeous, taut as a thriller, lovely as a watercolor by Jennifer Croft, and exceptional by Idra Novey, Misinterpretation dives deep into the human psyche. Based in present-day New York City, an Albanian interpreter reluctantly agrees to work with a Kosavar torture survivor during his therapy sessions and soon finds herself entangled in his struggles. As the client's dreams stir up her own buried memories and risky decisions stack up, Misinterpretation prompts readers to consider the boundary between compassion and self-preservation and to examine the darker legacies of family and country. Misinterpretation is out September 3rd from Tin House and available for pre-order now. Prior to 2022, sci-fi and fantasy conversations were a more regular part of the show, whether early conversations with William Gibson, Neal Stephenson, China Mieville, and Kelly Link, or more recent ones with Jeff Vandermeer, Nnedi Okorafor, N. K. Jemisin, and Ted Chiang, and, of course, the three conversations with Ursula K. Le Guin, 2022 was the year of Crafting with Ursula, where so many great writers, Karen Joy Fowler, Kim Stanley Robinson, Becky Chambers, and Adrienne Maree Brown, to name just a few, came on the show to discuss their work in relation to some aspect of Le Guin’s. But I noticed now, looking back, over the 18 months since that series ended, that I haven't yet returned to form with regular guests from sci-fi and fantasy. So as a first gesture in that direction, it makes me happy that the last conversation, with one of the most exciting new voices in the genre, Vajra Chandrasekera, is followed today with Grandmaster of Sci-Fi and Fantasy Nalo Hopkinson, about her first new novel, in over a decade, one well worth the wait, the remarkable Blackheart Man. Like the book, the conversation is about many things, the intersection of fantasy and history, the oral versus the written, about Caribbeanness in Nalo's alternate history of the archipelago, a history that is also a fully imagined different culture with different gender and family dynamics, racial politics, and more, and yet a conjured civilization that is animated by something that remains distinctly Caribbean in mode, gesture, sensibility, and speech. Also a conversation about writing challenges, navigating challenges of arriving to the page, whether the obstacles are material, physical and bodily, or cognitive. Like the conversation with Vajra, it is one for the ages, I think. If you enjoy conversations like this, long-form, in-depth explorations that take their time and create the space for nuance, complexity, and even contradiction, if this is something of value to you, consider joining the Between the Covers Community as a listener-supporter. Every supporter gets resources with each and every conversation, pointing you to what I discovered while preparing and what we referenced during the conversation, and every supporter is invited to help shape the future of the show, who to invite going forward. Plus, there are simply a ton of other possible things to choose from, rare collectibles, including some great vintage 1980s Twilight Zone and Interzone Magazines that Karen Joy Fowler donated that include her work, or the Tin House Early Reader Subscription, which is often full and unavailable, but where recently a handful of slots have opened up all at once, where people get 12 books over the course of a year, months before they're available to the general public. Lastly, I'll mention, among many other things, the bonus audio archive, which is immense and ever-growing. Some examples in it include Daniel José Older reading a mesmerizing chapter from a forthcoming work, Ted Chiang reading an essay on why Silicon Valley really fears AI, to Vajra's translation from Singhalese to English of an excerpt of a short story that caused its writer in Sri Lanka to be jailed for anti-Buddhist sentiment. An excerpt he not only translates for us but reads and contextualizes. You can check this all out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today's conversation with none other than Nalo Hopkinson.

[Music]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest is Grandmaster of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Nalo Hopkinson. Hopkinson is the youngest recipient and the first woman of African descent to receive this lifetime honor from the Science Fiction Writers of America, whose past winners include Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, William Gibson, Samuel Delany, and Ursula K. Le Guin. Born in Jamaica to a writer father and librarian mother and raised in Guyana and Trinidad, Hopkinson moved to Toronto when she was 16, and Canada has been her home for much of her adult life. She received a master's in writing from Seton Hill University, has taught at UC, Riverside, and at Clarion, Clarion West, and Clarion South, and is currently a professor in the School of Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia. Her debut novel, Brown Girl in the Ring, received the Locus Award for Best First Novel, and she won the John W. Campbell Memorial Prize for Best New Writer. Her second novel, Midnight Robber, was a finalist for the Hugo, Nebula, and Tiptree Awards for Best Novel. Her first story collection, Skin Folk, won the World Fantasy Award. Her many other novels and collections include The Salt Roads, The New Moon's Arms, Falling in Love With Hominids, and her YA novel, The Chaos. Her 2013 novel, Sister Mine, winner of the Andre Norton Nebula Award for Middle Grade and Young Adult Fiction that year. In 2022, her short story, Broad Dutty Water: A Sunken Story, was awarded the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award for the Best Science Fiction Short Story, published in the previous year. Hopkinson is also the editor of many anthologies, including Whispers from the Cotton Tree Root: Caribbean Fabulist Fiction, So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction & Fantasy, and is co-editor of the British Fantasy Award-winning People of Colo(u)r Destroy Science Fiction special issue of Lightspeed Magazine. She's the 2018 recipient of the Octavia Butler Memorial Award for an author whose writing exemplifies the spirit of Butler's work and she's a founding member of the Carl Brandon Society, which aims to further the conversation on race and ethnicity in sci-fi and fantasy. Nalo Hopkinson is here today to talk about one of her two books coming out this year, not her upcoming short story collection Jamaica Ginger and Other Concoctions, which arrives this October, but nevertheless, to whet your appetite for the collection, I will read what Foreword said in its starred review of that book. “A commanding short story collection, Caribbean Canadian Nalo Hopkinson’s Jamaica Ginger and Other Concoctions blends ecological awareness, cultural heritage, and fantastical happenings.... Climate change is a recurring theme: there are diseased, parched landscapes and ravaging floods. Many of the characters are resourceful women of color who are determined to improve their troubled environments; they summon remarkable scientific, technological, and mechanical abilities to heal others and solve problems. Enriched with a marrow of emotion, the short stories of Jamaica Ginger and Other Concoctions move beyond bleak dystopian landscapes into a curious universe marked by damage and possibility.” Nalo Hopkinson is here today, however, to talk about her long-awaited, much anticipated new novel from Saga Press, Blackheart Man. Publishers Weekly calls the book “a triumph” and Library Journal says, “Hopkinson's latest is a mesmerizing novel about colonialism, magic, and myth. Hopkinson's incredible skill for worldbuilding is obvious. Every piece of lore, magical element, and unfamiliar word is seamlessly layered into the story. The world feels alive far beyond the text. The characters are painted just as richly. The politics of race, class, and colonization cause dangerous island-wide conflict, but personal questions about love, family, and camels are equally engaging. Much like the Blackheart Man of legend, readers will be swallowed whole by this novel and reemerge completely changed.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Nalo Hopkinson.

Nalo Hopkinson: Thank you so much, David. Thanks for having me.

DN: At the beginning of the advanced reader's copy of Blackheart Man, there's a note to the early readers of the novel from the editorial director of Saga Press Joe Monti. My small connection with Joe is that back in 2018 when Ursula K. Le Guin passed away, Joe reached out to me, having read a tribute that I wrote to her that originally had the title: The Holographic Universe of Ursula K. Le Guin, but when it was published by Lit Hub, they changed the title to Editing to the End. Joe reached out after reading it, suggesting we meet for a drink when he was in town for the memorial. At the beginning of your new book, Joe recounts curating a reading series in Chelsea around the time your first book came out 25 years ago now, how you, after winning some major awards, were the “it” writer, so much so that DJ Spooky, a sci-fi fantasy lover himself, gave up a big gig in Germany to provide background music for your reading of a scene from a forthcoming book, the book that would become Midnight Robber. Joe calls it the most alive reading experience of his life. Then he flashed forwards a quarter century to 2021 when you became the youngest person at the age of 60 to be named a Grandmaster and then Joe notes thinking of how this is your first novel in too many years that “Sometimes life is a crooked way forward.” He finishes by saying, “I'll give you a clue how I feel about it. As I first read the draft, I thought of Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon.” So the reason I start here with this looking back across time and also Joe's phrase, “Sometimes life is a crooked way forward,” it's because Blackheart Man has, I suspect, had a very crooked way forward to arrive to this moment. For instance, as I prepared for today, reading various interviews of yours from 5 years ago or 10 years ago or 15 years ago, if an interviewer asked you what you were working on next, it was often Blackheart Man. I, like Joe, love this novel, but given that this show is listened to by many writers, art makers, translators, and aspiring people in all those fields, I was thinking maybe we could start with the crooked way forward. Maybe you could tell us a little bit about the novel and you alongside the novel in terms of how it arrived to this moment?

NH: Yes, I can. Yes, Blackheart Man took a long, long time to work on. I got it most of the way to finish many years ago, but it wasn't close enough for my then publisher, so they canceled it, and I had to revisit, which ended up being a good thing because it needed work. But at the time, when I turned it in, the first time, I was too inimic to write a novel. I literally could not read to the end of a sentence, much less write one. I kept having to start over and start over and start over. It was a really troubled process to get it to where it is now. But even though after I'd had to have that book canceled and for many years couldn't look at it, every time I did take the courage to look at it I still really liked it. I liked what I was doing. I was proud of what I was doing. I thought I was doing something fresh. Fifteen years on, it may no longer be fresh, but it is to me. So many people were encouraging, when they heard excerpts,

a former postdoc of mine invited me to join a co-writing hangout that she had developed. That was how I found and finished it. It was a meeting 8:30 every morning with those women, some academics and not who were all working on writing or something to do with their careers. So, yeah, I think it's the Jamaican saying that evil travels in straight lines. [laughter] So I guess by corollary, one might assume the book is good. [laughter]

DN: It really is.

NH: Thank you.

DN: We have a couple of questions from others that happen to not be about the narrative of Blackheart Man, but rather about the narrative of you outside of the book with the book. I thought I would put those up front. We can spend a little time longer on this period, this indeterminate period with you alongside the manuscript. Then afterwards, after these two questions, we can properly dive into the world you've created. Our first question is from Nisi Shawl. Like Blackheart Man, Shawl's first novel was also alternate history. Theirs was set in the Belgian Congo, the 2016 Nebula finalist and contemporary classic Everfair, whose sequel Kinning came out at the beginning of this year. They're also the co-author of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction, among many other books. Here's a question for you from Nisi.

Nisi Shawl: This is Nisi Shawl, and I wanted to ask you, Nalo, this question. Well, I'll set it up as, so we are often told as writers that what we learn as we write a novel is how to write that novel. So what did you learn while you were writing Blackheart Man? Can you share anything with us about how you wrote it, what you learned by writing it, how you learned to write it as you wrote it? Thanks.

NH: Big question, especially since my memory does what it wants to when it wants to. First of all, I want to thank Nisi because they have created a tea blend to celebrate this novel of mine, tea blend called Blackheart, that I had the honor of tasting last week when they sent some of it to the Clarion Workshop where I was teaching. It's lovely. It's yummy. What did I learn? I learned that camels are one of the most extraordinary creatures on this Earth. I mean, the common wisdom is that children and animals will steal your story away if you're trying to write something so be careful and I know this but I'm a little ornery so I learned that putting not one but perhaps 13 children in a novel [laughter] is going to mean escapades and is going to mean the copy editor having to save my cognitively challenged ass by figuring out who was named what, who was what gender, who was alive at the end and who was not, spoiler. I learned that. That doesn't mean it's going to stop me from writing children because how much fun they are so willing to take things in ways that the plot doesn't want to go. I learned that there is a lot of value in liking what you're creating. That alone, for me anyway, can keep me going when I was despairing of the novel ever getting finished. So to respect what you're doing, those are some of the things that come up. If others come up as we're talking, I'll interrupt us with them.

DN: Okay. Let me extend Nisi's question for another beat. One thing that I find both moving and generous on your part in interview after interview, including today already, is how matter-of-factly and readily you discuss various life challenges to get you to the page. You've talked frequently and movingly about your several-year period of homelessness and how you were held afloat by many small but vital acts of support from various people in the sci-fi and fantasy community. You talk about how your learning disorders and fibromyalgia and ADHD impact the act of writing for you. You've discussed the stress of navigating the consequences of breach of contract on this novel in its earlier iteration years ago. All of these things, most writers keep behind the curtain. I think because of that, they feel extra helpful and useful to hear them. But thinking of Nisi's question about “What did you learn?” I wanted to ask about the other things you were doing in the decade between novels to see if any of them influenced both your ability to finish the book, but also how you finish the book. For instance, for several years of that time, you worked on comics for the first time in The Sandman Universe. You said on The Caribbean Science Fiction Network Podcast that it has changed your relationship to plot because you were required to plot in advance, which you had never done in your own work. This decade seems particularly marked by collaboration. Deep collaboration with the comics themselves, of course, but also you collaborated with Nisi on a story called Jamaica Ginger that you wrote together for an anthology called Stories for Chip that celebrated the work of Samuel Delany. Lastly, as you've already mentioned during COVID, the writer Cathy Thomas pulled together an online writing group of academic women, largely women of color, where there was an open window on Zoom every day to co-work alongside each other. So as an addendum to Nisi's question, I wondered if comics, collaboration, or anything else during this time period outside the book became part of it, part of bringing it home to its final form. If so, how?

NH: Definitely all those things contributed in some way. Working on comics, as you said, is a deeply collaborative process because I'm writing script and then it goes to artists and three or four artists each in charge of a different aspect of thing and then it went to a bunch of editors. I was learning comics writing as I went, so the first two issues of The House of Whispers, I had to rewrite eight times.

DN: Did you say 8 times or 80 times?

NH: I said eight, eight. There wasn't room for 80. [laughter] Because the thing had to come out once a month. I learned a bit more about collaboration when DC asked if I would like a co-writer. I said, “Yes, please.” They paired me up with Dan Watters, who was writing Lucifer in the same new Sandman series. He's quite experienced both as a comics writer and as a collaborator, he was wonderful to work with and helped me work out some of that plotting ahead of time that was being so oppressive to me because I'm a pantser, not a plotter. How it's played into my current writing, I'm not entirely certain. I'm less scared of plot. It was gratifying to discover that even with stories that Dan and I had heavily plotted, I was still finding surprises within the stories as I was writing them, that kept it fresh for me, that the plot is not a straight jacket. You can mess with it at any time. I learned how it was possible to collaborate with people in a way that made the result better than either of you could together. For instance, my main character is Erzulie in the comic. She is a goddess from the Afro-Caribbean pantheon, Yoruba patheon. I have her living in New Orleans on a boat and we open with a party on the boat. I write that, then I hand it to Domo Stanton who was the anchor and he decided that it wasn't just a boat, it was one of those grand New Orleans river boats, that of course, you can hold a big ball in and the chandeliers and he had dancing boys. It just clicked so much better, of course, Erzulie is this goddess of plenty and wealth and sumptuousness. Yes, she's not going to live in a little houseboat. [laughter]

DN: That's great.

NH: Yeah, yeah.

DN: Some of the anecdotes about Samuel Delany and you that I gleaned from preparing for today include a moment you point to as pivotal in your 20s. When you turned over one of his books and saw his photo and realized this was science fiction by a Black writer, something that you had not encountered before, and also not knowing until then that he was a Black writer, later you studied under him at Clarion, and then in an interview you did with Terry Bisson, where he listed a whole bunch of authors, Delany, Butler, Le Guin, and others, and then asked you to respond about each one in one sentence each, for Delany, you said, “All hail the king.” Here's a question for you, a final question outside the book. Then we'll start to explore the book itself. Here's a question for you from the king, Samuel Delany. I should say that it cuts off abruptly in the middle of the last word, the word writing so we can all fill the word writing. You sort of know it's the word writing, but we can all in our minds complete the word from Samuel Delany.

Samuel Delany: When I retired from Temple, it occurred to me that if I had retired three years earlier, I would probably have had another fairly sizable novel in my bibliography. I'm wondering, Nalo, if you find that teaching is easier than writing, plus the fact that it gives you an income, a set income that you can count on that it tends to edge out writing.

NH: First of all, my God, you're a thorough researcher. [laughter] Thank you so much for getting that question from Chip. Oh, so sweet. Yeah, the dilemma of teaching versus writing, I don't find teaching easier because it requires more outward-facing organization than my ADHD brain can easily manage. I love the actual being in the classroom, but it is not easier. It does take up a lot of brain space. Yes, in that sense it does edge out writing, not because it's easier, but because it's harder and because it is the thing bringing in the income. And because you just want to do the job, you've got all those people counting on you and you want to do a good job. So yes, teaching does edge it out a little. On the other hand, the questions and the insights that I get every term from students, I think, help push my own craft because they'll ask questions that you think, “Well, that's obvious,” and you realize you have no idea how to answer it. Or there will be something in a particular person's writing that you keep pointing out and you keep being irritated that they're not listening to you and then you think, “Why am I so irritated by this?” and you realize you're sensitive to it because it's something you do in your own writing. [laughs] In that way, it keeps me honest and it keeps me curious and engaged. So, yeah, it's a trade-off. [laughter]

DN: In Locust Magazine recently, you talk about how, while the new book has many elements that your longtime fans will recognize, that nevertheless, this new novel is different, a departure in some ways, not just in terms of what you've written before, but in terms of Caribbean fantastical literature more broadly. So I was hoping maybe you could talk to us about this as you orient us to the setting and scenario of Blackheart Man.

NH: The thing is, because it took me like a decade and I have to write it, that statement is now only partially true that it's new. I mean, we've seen novels from Leone Ross that created not just an alternate history, but an alternate Caribbean altogether. So it's happening more and more. Yet, the Caribbean literature with which I grew up tended to be very much set in the consensus world, creating an alternate history and an alternate set of world-building when you're already underrepresented, probably can be a stretch too far, but because I grew up in fantasy where that happens all the time, it was perhaps easier for me to conceive of. The book is a departure for me personally. It's an expansion for one thing. It's taken my obsession with language and spoken language and just completely pushed it because I had to come up with a 16th-century Caribbean language from a country that never existed, and then to do it again for the 18th Century and to do it for different socioeconomic registers. I've done that a little bit in the past, but not this much. It also, in the way that it deals with magic, I remember my agent reading it and calling me up to talk to me about it in the first draft and he said, “You break magic.” [laughter]

DN: You break magic?

NH: By the end of this, you break magic. I hadn't thought of it that way and I kind of do. [laughter] That's also departure. Usually, you start the world with magic. Maybe it's not that obvious. You end the world with magic. This one, I'll leave it up to readers how it ends. The other thing was writing a male character or male point of view character that in some ways is no different from writing the character of any gender, but also there are those going to be things that are specific, not just to masculinity, but his type of masculinity and to himself as a person. That was a challenge for me. There is a sex scene in the book that took me many, many years to just buckle down and write it because I was writing so outside. I was writing two men having sex. I need to get this feeling plausible. I kept pushing my comforts that way, as one does.

DN: Your book takes the real phenomenon of maroon communities, communities of previously enslaved people living autonomously and imagines that they weren't ultimately subdued. In Blackheart Man, it is a 200-year period between the time they fight off the colonizers and the current day of the novel when the colonizers have returned for the first time since, under the rubric possibly of trade, but with the subtext of possible invasion and future subjugation. You've said that there are echoes of the 17th Century Community Palmares in Brazil, a maroon community that lasted a century and had between 11,000 and 20,000 people, the largest fugitive community ever in Brazil, and one that was governed using Central African political models blended with aspects of both local and European models. In my reading about it, there were six Portuguese expeditions that tried to conquer them but failed until an army was ultimately raised to defeat them. I appreciated the excuse to go and read more about this community called Kilombu, which is also the name of a movie I saw long ago when studying Portuguese. But I also learned some interesting things reading your book about the Caribbean in a backwards sort of way too. For a while, I wasn't sure if this was supposed to be a fantastical Caribbean at all because there were elements that seemed definitely, at first to me, from elsewhere. For instance, the traffic in the main town was horse, donkey, tricycle, and camel, and one of the main spices was nutmeg, and I made notes of all these things as I was reading, and in my ignorance, I associated these things with other parts of the world. But then later when I went and looked them up, lo and behold, camels were actually used in Cuba, Tobago, Jamaica, Barbados, and other places in the archipelago for several centuries, and Grenada is today one of the largest nutmeg producers in the world. You've done this in other books. For instance, with the swimming pigs, the swimming pigs of Bermuda, the pigs that were left once on a deserted island, which now swim out to boats seeking treats. There's a slide nod to them in this book, too, very much in passing when you refer to the deserted Bore Island. These details all feel really fantastical, but they're actually all real. But given, as you say, that one way this book is breaking new ground in Caribbean fantastical literature is that you're not only doing alternate history but creating an entirely new culture within that alternate history, let's do a little bit of the world building together for listeners. I was thinking maybe we could start with the cosmology of the twin goddess, Mamacona, and how it functions in the society.

NH: I'm not the only person to have said that the history of the Caribbean is so complex that it can make sense to resort to the fantastic world to try to represent everything that's going on and it's been hybridized and realized into it. Mamacona is a twin African goddess I create. I'm often using African-based riverine goddesses, water goddesses. I knew I wanted Mama-gua, a nod to Mamadjo, who is Mama [inaudible], who's a version of [inaudible] who’s a part of that pantheon. Knowing what I know about what happens to language, I pushed two words together to get Mama-gua. Then thought, when I decided she was a twin goddess, I used the fact that the island's, one of its main sources of industries, the Piche Lake. That can be a goddess, so she's Mamma Piche. To put them together, I believe I was probably drawing on the Haitian woman revolutionary Anacaona and just stuck Mama and Cona together. So yes, I'm hybridizing the already hybridized, the fact that Grenada, the Spice Island has such a lockdown on nutmeg, nutmeg was brought there by the Dutch who then proceeded to try and control it and would sometimes travel to this, I think then independent island and burn down nutmeg plantations in order to be able to control the price of nutmeg back home.

DN: Wow.

NH: Once you start looking the history up—I mean, you can ever only know bits of it from living there, and I do. I have done—once you start looking the history up, there's so much to draw on that at some point, I have to decide whether it matters how legible that is to people or whether I'm just going to make a world that the experience of it can stand on its own or maybe future grad students will have a field day looking it up. [laughter] I sort of hope both.

DN: I hope so too. I wanted to ask you about your interest in twins. In this book, we have the twin goddess Mamacona, who has her seaward aspect, Mama-gua, and her landward aspect, Mama Piche. We have someone who serves as her human avatar, always a child from what is called a twinning birth, who is born of a mother without a father involved in conception, where the child herself is a twin of her mother. But there's also an interest in twins and doubles in your writing before this, the clones and your story Message in a Bottle, the twin sisters in the story the story East Hound, but most notably your last novel, Sister Mine, which also has twinned semi-divine sisters, in this case, conjoined twins, that when separated, one retains magical powers and the other does not. It made me wonder if there's something that attracts you to twins and doubles, generally speaking, but also maybe twins and doubles when it comes to women and to sisters more specifically.

NH: I mean, does one ever really know why one is drawn to something? I know that even though I am not a practitioner of Yoruba, one or two, depending on how you count it of the other gods, are the Ibeji, the twins, who have various significances and various aspects of the religion as it was taken out into the diaspora. I'm also fascinated by the idea of parthenogenesis. So really in Blackheart Man, the girl who is chosen is a parthenogenetic child of her mother. She's a clone. She's a natural clone. To my disappointment, when I looked up the biology of parthenogenesis, I discovered that it's actually not possible for it to happen in humans. It so neatly explained Jesus, [laughter] or at least part of Jesus, he’s being mailed through a spanner into the works. But it's just not possible. Then I remember it, I write fantasy so I could do what I want. [laughter] Yeah, there's something about being able to be a community unto yourself. There's a type of, they're called stick creatures. It's an insect that's related to, I can't remember the name of the animal.

DN: Is it a praying mantis?

NH: Yes, right.

DN: That's what your hand looked like, the gesture you were just making. [laughter]

NH: Yeah. So there's a type of insect, they're called stick creatures. They're related to praying mantises. There's a small community of them somewhere, I forget where, where all the males died out quite a while ago and the females started reproducing viral pathogenesis. So all of them are related to each other as identical going down the generations of this creature. I'm not sure it would know what to do with male stick creatures if you reintroduce them and it doesn't need them. There's something about that fact that life will find a way that we keep going somehow no matter what, we’ll change our biology if necessary, something will happen that I find really profoundly hopeful given that humanity can be simultaneously such a f*ck up and so resourceful and interesting and social. The fact that we might keep going despite ourselves says a lot to me.

DN: Yeah. Well, as a first step toward introducing our main character, it feels important to mention gender in your worlds as a preface to that. You've long envisioned worlds outside the gender binary. Your story Fisherman follows a trans fisherman, Something to Hitch Meat To follows workers at a company making porn for straight men but many of whom are largely not so, and the world of Blackheart Man is deeply woman-centric, whether we're thinking of the legend of the three witch women who liberated the island 200 years before to the fact that only women and third sex people can captain a boat. It's a deep part of the fabric of this culture, but perhaps the most profound difference from our world is the family structure, as marriages are of three people, usually two husbands and a wife, and there's a long engagement period for any love triangle to be when people can be sexually promiscuous with whomever they want. It also seems like more people than not are bisexual. The social structures are very fluid with regards to sexual freedom in many ways at once. We'll talk more later about how this family system informs the narrative itself, but let's introduce our protagonist to listeners, a main character who, in this matriarchal world, is a cis man, bisexual, indigenous, and really an utter delight to have as our lens into this world, both I think for the comedy and tragedy he produces and also for the ways he has his feet in different worlds simultaneously as a border crosser of sorts. So introduce us to Veycosi a little bit.

NH: Veycosi is what happens when Nalo tries to write an entitled stoner grad student.

DN: [Laughs] Entitled stoner.

NH: Yeah. Entitled stoner grad student, because that is what he is, but as you noted, he is indigenous, he's Caribbean. He is queer, which is not an issue in the world of the story. I wouldn't say that more characters are bisexual than not. It might be that those are the ones I focus on. There's a lot that was ripe and ready for Veycosi, he is about to graduate from the Islands University, which finds and collects lost books, books that have been lost to history into war. For his graduation process, he has to go out and collect one of these books that he has sourced. We probably all know people like him, and they are often, but not always male, often young, privileged, not exactly aware of their own privilege, very aware of fair and unfair, but not always really nuanced how that plays out in the real world, very intelligent, sure that they know the answer to everything and that their way is always best because they can see it the most clearly. So they hear about just messing things up through their own inability to be humble. [laughter] He means so very well, but he is just getting in the way of what people need to do. He is not understanding the lives of people less privileged than he. His solutions are often just inconceivable to anybody else. He has a lot to learn. As much as writing is only partially fun for me, he was fun to write. I never knew what he was going to get up to next and I'd get a flash because I'm not writing linearly, I'd get a flash of an image and think, “But how in the world would he survive that? Well, I have to put it in the book now because I have no idea.” [laughter]

DN: I love that.

NH: There's a deep compassion to him. Even as he's a f*ck up, there's a deep compassion to him. That's his saving grace.

DN: Well, now that we have a rough preliminary sketch of the world you've built, I wanted to ask you whether it references other books or other works or whether it comes more right out of your forehead like Athena did, fully armored right out of Zeus's forehead. The reason I ask is because of how some of your books, from the beginning of your career, have been in conversation with other stories in some way. Your father was one of the actors and playwrights in Derek Walcott's Trinidad Theater Workshop and your debut novel, Brown Girl in the Ring, took the framework from one of Walcott's plays, Ti-Jean and His Brothers. In your second novel, Midnight Robber, you have an AI supercomputer called Granny Nanny, but in our world, Granny Nanny is a legendary Jamaican woman who fought off British soldiers, eventually gaining freedom for a maroon community in the hills of Jamaica. A woman so legendary that you've said that the British soldiers thought she could catch their bullets with her butt cheeks and fart them back like a machine gun, which is amazing. Sister Mine has a relation to Christina Rossettii's Goblin Market but also makes nods to West African deities with characters like Grandmother Ocean related to Oshun and General Gun to Ogun. You've also talked about how when you visited Kamau Brathwaite's literature class at NYU, you had the realization that Ariel and Caliban in The Tempest could be seen as the house negro and the field negro respectively, which went on to inform your short story Shift. More generally, you've talked about how folktales are great for learning dynamic storytelling and how to structure a plot with forward motion. So all of which made me curious if there were any ghost books or ghost tales haunting this one.

NH: You know, I'm sure there are, but I think with this one, I would have made any references so sly that I myself don't remember them at this point. I know there was one thing I did right at the beginning where it's not so much a book as a field of knowledge. Veycosi is standing on a cliff looking out over the water and he describes the wave pattern as a seed scale, which is straight up from fractal math. I just took the phrase out in fractal math and put it in because I knew what he was describing was fractal. For me, that's part of the joy of writing in this mode that is science fiction and fantasy, is that it is so pastiched. It really, in many ways, looks at the structure of story to tell its stories. So it's kind of meta that way. I do enjoy nodding to things. I have nodded to the hidden library of Timbuktu where it was discovered that under pressure of war, people had taken precious books that would have been written by hand and bound by hand and hidden them, sometimes underground, sometimes in hidden cupboards. There was a whole unseen library underneath Timbuktu.

DN: It was done by a donkey, too, by the way. I don't know if you know that. They emptied, I don't know if it's the National Library, the National Museum, but by donkey to hide it in all these people's basements before, I think it was ISIS, before ISIS or Al-Qaeda arrived.

NH: Yeah, I love human beings. [laughter] Because the story of The Great Library of Alexandria can still bring tears to my eyes. You burned books, my God. To have a library that saved itself is where I originally got the idea for this university does this as a practice, that it finds books, books being one of the non-human casualties of war, knowledge being such, that it finds books and saves them and commits them to memory in a way that it cannot be destroyed. So there is that. There's the folktale. It's a Taino folktale from, I believe, Trinidad, of the village that killed and ate a hummingbird. Hummingbirds were sacred. They were not to be killed. The next day, the Pitch Lake, because Trinidad does have one, the Pitch Lake rose up and covered the village completely. Some of that is hovering in there. It's where you get the colibris who were not hummingbirds, but that was their original inspiration. I looked up one of the tiny words for hummingbird, and it was colibri. I thought, “All right, if you're coming in with an English that just homogenizes everything to English-speaking patterns, you would turn colibri into colibri. There's all kinds of stuff like that to be found; a lot of it based in older stories. Some of it based in modern forms of knowledge, modern writing. I do it as such a matter of fact that I forget.

DN: Well, one of the tales that exists both inside your world and in ours is the tale of the Blackheart Man. I was wondering if we could hear the brief version as it manifests in your imagined world at the beginning of Chapter 6.

NH: The Blackheart Man story, as it comes from Jamaica and Trinidad, is a tale of a man who's a predator upon children who comes at night in a black carriage or a black car, depending on when the parent is telling the tale to try and scare their children. He's a horrible man who hunts children and eats their living hearts out of their bodies. That's pretty much the story. It's told to scare children. I'm pretty sure it's not told anymore. In Barbados, they call him the Heartman. It might actually hark back to something that happened. It might not. But just this powerful idea of this predator, this silent predator in a black vehicle so that it fades against the blackness of night, you can imagine why children would have been scared. So I rang the changes on Blackheart Man as I went through the novel, and I created sometimes folktales that don't exist. This one in chapter six about the man who hunts and eats the cascadeur of fish and its eggs, near as I remember, completely out of my own head, and the unfortunate, but very tragic thing that happens to him makes him out of sorrow and grief become black-hearted. I played a lot with the word blackheart, which probably also is where we get blackguard. What does it mean to have a heart that is black? What does it mean? It's not just terrifying, it's probably also very tragic. The thing that happens to Titen, that causes him to throw himself into the liquid middle of the Pitch Lake, the consequences of his actions cause him so much grief that he's referred to as being black-hearted. That was something that came much later in writing the novel when I wanted another iteration of this idea of The Blackheart Man.

[Nalo Hopkinson reads from Blackheart Man]

DN: We've been listening to Nalo Hopkinson read from Blackheart Man. Well, before we look at the ways you explore power and race in Blackheart Man, I wanted to step away from the book and look at these questions in relation to you and the science fiction and fantasy community in the world first. As I see a connection between how you position yourself there in the world and how you do so within the narrative of this novel, PM Press has this great series of books called Outspoken Authors that each center an author and past Between the Covers guests Karen Joy Fowler, Jonathan Lethem, Kim Stanley Robinson, and Ursula K. Le Guin all have books in this series, as do today's cameo questioners, Samuel Delany and Nisi Shawl. These books often include a long-form interview as well as a medley of smaller pieces by the author. In your book, which is a really great book, it contains a really substantive interview of you by Terry Bisson, some less-known short stories, and the speech you gave at the 2009 International Conference of the Fantastic in the Arts called Report from Planet Midnight, which is also the title of the book as a whole, the theme of that year's conference was Race in the Literature of the Fantastic, and as an invited guest speaker, you were already anxious about this talk before RaceFail happened. But then RaceFail happened between the invitation and the delivery of the speech, which only made the lead-up to this speech all the more fraught. I could try to give a summary of what RaceFail was in its broadest strokes, something that started with a White writer making a post with tips about how to write the other. But I know you could do a much better job than I could. Before we talk about your speech, how would you orient people in the most general way to RaceFail, to people listening today who aren't following the controversies in the sci-fi and fantasy world? How would you characterize it to them?

NH: In 2009, I think started not by that writer, who's Elizabeth Bear, but started around her post about why White writers should write characters of color, should not step away from it. That post that seemed to me fairly innocuous at the time. I came back a couple of days later and the thing had blown the hell up. It blew up into some long overdue discussions on race and racism in science fiction community, which had been happening in small ways for quite some time. I think by the time the discussion died down, you could find some 20,000 posts by people, everybody from fans in the community to writers to editors discussing and arguing about and fighting about and screaming about race and racism in science fiction and fantasy community. It's a community that has been liberal from the beginning, that has thought of itself as inclusive from the beginning, but that hadn't always understood what inclusivity really meant. That inclusivity isn't welcoming people because they have the same idea as you and the same history as you, that it is a more nuanced conversation than that. RaceFail began the process, I think, of having that understanding be more nuanced and further spread out into the science fiction fantasy community. It was scary because you knew that anything you posted, what happened to Elizabeth could happen to you, especially as perhaps a woman of color trying to take part in these discussions, you knew that it was a very tense issue, that it was something that affected people deeply. It certainly has me. So speaking to it was frightening. When I got invited to be the writer-guest of honor at ICFA and the topic was race, I knew I had to speak to this. It was terrifying. The final version of the speech didn't actually come to me until a couple of hours before I had to give it because I kept trying different versions of it and it wasn't working. The final version came out of a creativity born of terror that the deadline was coming. [laughter] “My God, the deadline is coming.” But I did it as a part performance piece, part speech.

DN: Well, I absolutely love this speech. It's amazing to learn that so much of it came together last minute. It's a speech where you are, for part of it, possessed by an alien ambassador/translator, one who's been studying us, but also one who has earnest questions and confusions that they hope to get clarity on. Some of the things that the translators of this alien people have been confused about and wanted clarification include when humans say, “I don't see race,” which they understood as, “If I keep very quiet, maybe you won't see me and ask me to do any work,” and, “I'm not a racist,” which they have two translations for. One, “I can wade through feces without getting any of it on me,” and two, “My sh*t don't stink,” [laughter] where they ultimately, after all of this, presenting this to us for clarification, where ultimately they say, “Our dilemma: To us, someone making this kind of delusional claim is in immediate need of the same healing treatments we offer to people who are convinced that they can fly. Such people are a danger to themselves and to others. And yet, the communications from your world are replete with this type of statement from people who do not seem to be under treatment of any kind, and few among you take any steps to limit the harm they do.” Another part I really love is the contemplation on book covers, how the original cover of Midnight Robber has a brown-skinned girl with Black African features, but the Italian cover of the same book has a blue-skinned woman with European features, straight hair, wearing a bra top and a fringed miniskirt. They note how they see these blue-skinned people everywhere in sci-fi and fantasy, but nowhere in the world itself. With no small amount of anxiety, they're worried about and want to inquire about the fate of these now-disappeared blue people. [laughter] What would you say to these aliens about the preponderance of blue people, whether Avatar or your own characters having been turned blue?

NH: [Laughs] And to the god, Vishnu, often being shown as being blue. As I understand it, he's representing somebody with dark skin in a Hindu culture that valued lighter skin. What would I say to these aliens? I would say, watch your back. I would explain why the tint of blue is often a way of evading actual clear racial markers of people who are not White. I would say, although, yes, watch your back, be careful that they—and you as aliens, because they call us aliens too—can get disappeared. Chances are you won't entirely because there's always resistance. But that if they substitute every time they see a blue character in our storytelling, if they try on dark skin on them that is actually in the colors of skin that humans come in, they might learn something about dominant cultures, attitudes, and guilt about racism.

DN: The real reason why I bring this speech up and RaceFail, beyond the joy in sharing all these amazing moments in the speech, is that the thing I like most about the speech is also a quality I like most about Blackheart Man, something that I think makes the book more complex and deeper. In the speech, the alien ambassador who possesses you for the first half makes clear that his people are fallible, not just because they can't find a consensus around the translations. They're not an agreement about how to translate all of these commonly used euphemisms and human culture, but also because they themselves are suffering their own cultural problems, their own issues with race in their own specific context. They don't come from a place of superiority or purity. Likewise, you present yourself in the speech as fallible and also assert that it's what you do after you make a mistake that counts. Once you return to being yourself in the talk, one of the things you focus on is labor or work, how both magic and technology are ultimately labor-saving devices, and also just how much labor in the real world it takes to even keep one human life going, and how certain portions of society are kept indefinitely disenfranchised, to do the drudge work to keep other people's lives moving forward, how both fantasy and sci-fi have the potential to use mythmaking to examine and explore ethno-racial power imbalances. You recount in the book version of the speech that right after the talk, someone approaches you and asks you if you were a Marxist because you “reduced” the lofty subject of art to a mere question of labor, where you end by saying, “You can’t convince me that art and the labour that creates it can be easily teased apart and considered as separate objects, and you sure as hell can’t convince me that the latter is somehow base and impoverished in comparison to the former.” These questions are really alive in Blackheart Man, both the question, I think, of being fallible, even if you come from a people with a long history of being victimized, that even if you are a victim, you still very much can move into the position of victimizer. Also this question of labor, most decidedly, I think, this is evident with the Mirmeki people. I was hoping you could talk to us about the Mirmeki and what they tell us about the dominant culture of the book. Because the dominant culture of the book is a culture that has been victimized and one that might soon be again. Our narrator is speaking from within that culture, and because of that, with all of that culture's blind spots.

NH: I finished this book years before Israel attacked Gaza again. The fact is that human beings, we create stratified social differences and then treat people as better or worse based on the one stratum that they're in. That happens right across humanity. It's not an unfamiliar thing. Yet, Chynchin, the island where Blackheart Man takes place, has been created to try and abolish those stratified social differences. It's gotten a long way but it's also working with the fact that we are human. So the first thing I thought of was labor, the kind of work that nobody really wants to do that is the least paid, that is the physically hardest, that is most demanding. I thought, “Well, if you need a society to run, those things have to happen. Can't have nobody doing them.” The best I could come up with is people sharing them. So, many of them are tasks that don't necessarily take a high level of expertise. That's not exactly true. Even the lamplighter needs to know something that you can't just figure out from watching her do it. But they share tasks like the lamplighting every evening, like taking out the night soil in the morning. We share the menial tasks. Of course, people being people, you can imagine that somebody might go, “I don't feel like doing my route this week. How about I give this guy something that he can't always get to do it for me?” So you pass off the labor. Science fiction and fantasy seems to be always wrestling with this question from the first robot in Rossum's University of Robots where the word comes from. It's always about: we are complicated, we need a lot of work to stay alive. Nobody wants to do the menial work, but we're complicated enough that we can make machines that will do it for us. Okay, problem solved, until the machines become so complex that they have their own agency. Then who does the work? So we keep pushing the problem forward and we don't yet have an answer to the point where we get to AI that are using up so much resources to do and that aren't really intelligent. We're afraid they're going to take over because we don't really like ourselves and we think anybody would. It's part of what I'm wrestling within the book and I couldn't put up with an answer. The best I can do is present the problem. When I decided to take money out to the equation, it makes it even more complex. Society that runs about money. So then who does the menial work and why? I came up with some answers for that. One of the intriguing answers is that it argues against economies of scale because money replaces huge swaths of labor it stands in for it. When you don't have that, you don't have exponential out to control the growth of a society. It's an island, its function is it’s going to stay small.

DN: Well, I love how we are with our protagonist Veycosi as he discovers counter-narratives to the world that he thinks he knows. For instance, all the language he uses is that the Mirmeki are shocked to hear, or that his own people are described by them as runaways, not freedom fighters, which equally shocks him. Or simply his eyes opening, I think, for the first time around questions of labor and servitude that aren't related to his own people's subjugation. I feel like there's a real generosity you give your characters in this regard as they stumble and fumble in real-time. To step back into the “real moment” for a moment and to the various times you've meditated on book covers, whether the blue people on the cover of one of your books, where you've mentioned the cover of Snow Crash that obscured the character's Japanese identity, and the many books throughout the years with characters who are Brown or Black in the narrative, but are made White on the cover, something that Le Guin battled against, among others. I think of all of this when I take in the amazing cover of Blackheart Man, which centers an Indigenous man's face flanked by the twinned black goddesses Mamacona. I wonder how much or how little you feel like things have changed since RaceFail. I know N. K. Jemisin wrote maybe a year or two after that some people felt like the fail in RaceFail was that it had happened at all. But for her, it was not only necessary, but unequivocally for the good. She welcomed more so-called fails. But how do you see things now looking back now, 15 years later, to then? Is this cover the sign of substantive material change, do you think?

NH: Yes, it is, and many other covers before it in the interim. It was, at one point, common wisdom amongst publishers that readers wouldn't buy a book with a person of color on the cover. That is absolutely no longer true as the world realizes that there are a whole lot of people of color. If you say readers, there are lots of us who actually read. That as the sensibility in science fiction and fantasy has changed, it is a community that has always been interested in cultures with which it's unfamiliar, learning things it doesn't know, still operate inside by each of that same systematic racism that you have to be really analyzing to be able to fight. But it has changed a whole lot. Going back to one of the Chinese translations of, I think, my first novel, Brown Girl in the Ring, where other translations had done that blue washing of the book, but the Chinese translation has a woman who not only has very clearly African features, but she's dark skin. In fact, she looks so much like a friend of mine, I had to go and get pictures to compare because I thought maybe they'd found a photo of her on the web. [laughter] That is a moment I never thought I would see going into science fiction. For this cover, Joe Monti, the editor, went and found an artist who, like me, is from two different Caribbean worlds, two different Caribbean nations, somebody who clearly did his research because that man's features are so very indigenous. I know it's already causing joy amongst readers to see themselves represented, that the way he does almost sort of Kandake, the profile of the two queens, two African goddesses behind him, is just so wonderful, the colors are warm, they're inviting, artist is just brilliant at what he does, is a marker I think of the fact that these things have changed. I'm not sure they've changed universally, but they have changed in my world so that there's less of a fight I have to do. To be fair, with my very first book and my very first editor, Betsy Mitchell showed me the original conceptual drawings for the cover, and seeing me, my face just went blank because I was thinking, “How much can I say here? This is my first book,” and Betsy saying, “I think we need something a little more urban,” and she was quite right because the book showed jungles, the cover showed jungles.

DN: Oh, wow.

NH: It's a book set in Toronto. But she was also talking about how the Black culture had been represented in that first version conceptual drawing. She took it back to the artist who fixed it, more than fixed it. I have been lucky, but also come from a Caribbean literary world that has been articulate about this kind of thing for a very long time so I have some of the language and it helps, I find, to always be ready to walk if you can't make someone understand to pack up your writing and take it elsewhere.

DN: Well, given that RaceFail began at least around that original post around writing the other, I had one writing question for you about writing the other. Love triangles are the default in this world, but Veycosi, in his premarital period himself, is at the nexus of two love triangles, one with his future husband and future wife, and one with a woman and a man that are Mirmeki. There is an epic sex scene, which you've already alluded to, in the book, long, graphic, detailed, and extremely intense between two men. I wondered if we could just spend a moment more on it and how you went about it, your thoughts about writing across difference, and also, for that matter, writing sex more generally, which is such a difficult thing to pull off, I think, in writing, or something that people sometimes avoid for fear of not pulling it off, let's put it that way.

NH: It took me 10 years to write that scene, I think. But, yeah, writing sex scenes, I think of it as any kind of choreography, writing dance scenes, sex scenes, or fight scenes. You need to be aware of leading the reader through the touchpoints between not just the characters with their environments and you need to be able to do so in a way that is unashamed of body and that recognizes dynamic movement. Starting my science fiction journey very early with the feminist writers to thank for, being frank about bodies, I definitely have Chip Delany to thank for doing that and for writing sex scenes that are fearless.

DN: Yes.

NH: In my first writing early on whenever I knew I wanted to write the sex scene and I'd be scared, I think, “What would Chip Delany do?” [laughter] Then I’d throw myself in. Part of what I do is I remind myself that when I'm writing it, nobody's seeing me, nobody's seeing the words, I can do whatever the hell I want. I can put anything down on the page, think about it afterwards, just get it down the page. That helps a whole lot because I find I have enough ego that if I manage to get through that scary process and then I look at what I've written and find it mostly good, I'm not going to just hide it. I'm going to include it in what I'm writing. Writing the other, writing the unfamiliar, I try to find not only the places that are different and I ask people about it. I have given this scene to people to read, who would know more about what it's like than I do. But I also try to find the places that are similar. Bodies are similar, sexual acts are similar, even if I'm pretending it's coming from a different type of character than me, the sensory nature of it, I know to be kind of delicate. [laughter] So I do it that way and I really, not realizing it at the time but realizing it now, drew on the romance trope of the two people who hate each other and are drawn to each other and finally, in one big burst of simultaneous hatred and erotic arousal, finally get together. [laughter] So once I finally wrote the scene, it wrote itself really, really quickly, despite my having avoided it. I have made some changes to it, but not too many, but anything that I felt I would have needed to make, I would have done.

DN: Well, I wanted to spend the rest of our time with the question of language and literature in the book, the aspect of your world-building, among many things that I love, that I think I was most enamored with. We know right as the story opens that books are sacred objects and perhaps, there's been a rupture in the archive, an erasure as Veycosi is involved in rescuing the last known copies of given books. We learn that there's punishment for destroying one of these books. But what I loved the most is that when a book is recovered, it enters the library, it's “shelved” when it is memorized and sung in its entirety before the community. Even books that are completely utilitarian are sung, so you might be listening as much to a book on hydrology as one of great literature. But clearly, the oral and the sung is treated with equal reverence to the written in this world you've invented, maybe more so, but both are for sure in a dynamic equilibrium with each other. It reminds me when I had the Irish writer Doireann Ní Ghríofa on, and she talked about the tradition there of Keens, songs that were “written” by women that were sung, memorized and sung, passed down, not via books, not via text, but woman to woman, body to body, through generations. But unlike the denigrated status of Keens compared to the written word in Ireland, in your world, it is central to the function of the archive and the library, the oral on the sung. It also reminds me of something you've said about the Caribbean, that there are no strict boundaries between literatures, that you could be at a literature conference whose guest speakers are Derek Walcott, alongside the dance hall singer Lady Saw, alongside Bell Hooks. Perhaps I wonder if this is an extension of that spirit of blending. But either way, talk to us about how you see the oral and the sung, the unwritten in relation to the written in the world of Blackheart Man.

NH: Yeah. For my very first book, the way I hit the voice I wanted was by channeling some of the Caribbean oral traditions of storytelling. So when I'm stuck, I can move into that. It will help me move past and help me seat myself in my own language again. For Blackheart Man, I am referencing griot tradition. So it's a West African tradition that is historian, balladeer, and the griots are musicians who sing the histories. I'm also remembering the way that stories get passed down. Folktales get told and told and told and they get changed, but essentially stay the same. And because they are in memory, they can last centuries. Songs are the same thing. We have songs we sing that come to us from God knows where that we are still singing because there's something about how we remember rhythm and music that gets passed on. We don't forget it. It will change, but we don't forget it. That was the closest I could get in 16th, 17th, 18th century of my story to digital recording. How do you make something where the knowledge cannot be killed? You make it into a song. Make it a catchy one and people will keep singing it and so it very naturally went to griot culture and fantasized it. It doesn't work like this. But I remember when I had the intuition that as earnest of having transmogrified this book into something that now will hopefully not die, they destroy the book, they don't actually, but they do a ceremony where they destroy a copy of the book to signify that it is no longer bound on paper. It has transcended paper. That I found really cool because I was also thinking of Timbuktu and of the now digital library of Alexandria or some of the texts have been recovered. So part of it was how, in a world that wants to kill you and your traditions, do you keep knowledge going? So when you talk about me referencing other texts, there are lots of references to older. I went and looked up lost books, some of which we only know about because somebody wrote about them a millennia ago and maybe quoted a little bit of them. Yes, it was everything from the sacred to the profane, it was everything from charts and how to lay pipe to various sexual acts. That was fun to look up and to refer to, to ground the book back into bits of our reality. I just love the idea of these people going out and going on a, it's like a vision quest where they spend their research as grad students finding one of these lost books. Then they go out into the world and bring the actual back and that's like catnip to a righteous heart. [laughter]

DN: I just love that and that they bring it back and it gets codified through singing. So great.

NH: Yeah.

DN: There are many ways you blend things that are otherwise I think kept apart, not just the oral and the written, not just the blending of what is considered literature and what is dismissed as not a part of it. I know that outside the book, you're interested in fabric and textiles. You've mentioned the website Spoonflower that allows you to custom design them. Another aspect of Blackheart Man is that it makes you incredibly hungry, as you're always describing the making of meals in detail, the conjuring of smells, the naming of ingredients, whether bammy cakes or the liberal use of chives and cinnamon together, which makes me suspect you're an amazing cook. Thinking of blending, of weaving, of cooking ingredients into a whole, as a first step to talking more about this element of the book, we have a question for you from someone who themselves is iconic for many discrete things, whether Roots or Reading Rainbow or Star Trek, and yet is also indelibly known as LeVar Burton. Here's a question for you from LeVar.

LeVar Burton: One of the things that can happen when you fall into Nalo's orbit is that you discover all of these other talents that she possesses. Nalo has a passion for tea. She's all about tea. My wife Stephanie is, too, they have that in common. They share that passion for tea. Over time, Nalo has sent Stephanie teas that she herself has blended, brilliant mixtures of different things. She's got one tea that Nalo sent that has Gunpowder Pearls in it. I love that. I just love the idea of drinking Gunpowder and Pearls combined. Anyway, my question is Nalo, when did you discover, not simply this passion but this talent that you have for speaking through tea, this talent for blending different elements in an elegantly alchemical way?

NH: [Laughs] LeVar is amazing. He is partly correct. I do love blending things to make new foods. I brought food to him and his wife and to his crew when he interviewed me for his podcast. But he's actually confusing me with somebody else. I think I know who I'm really very honored to be confused with them because the best person I have a lot in common and we share a love for food and share a love for making our own food. When you meet as many people as somebody like LeVar does, it's not surprising that he might occasionally mix two people up because I don't meet half as many people as he does. I honestly do not recognize people from one minute to the next. But he's got the essence of it. I took Caribbean Black cake for him and his crew when he was interviewing me. If ever there was a hybrid food, Black cake is it. It's a Christmas thing. The talent for blending and talking through food, I say we'd probably have started with my mother. My family tended to move every few years to a different country, usually in the Caribbean, but not always. We were not wealthy at all. It was on my mother who was the main cook. My dad did cook but not all the time. But it was on her to find foods that were nutritious and delicious. So she would go into the market and start pointing at things, say, “What is that? What do you do with it?” It's her ingenuity I think that I have been drawing on that's made me unafraid to experiment with blending in general. I guess I have imported it into my own writing, not only through food, but because it's also very much a feature of Caribbean writing. We come from so many different traditions, and different nations that to blend them is quite natural. The story of the Caribbean is a story of hybridization, story of realization. It's a story of many cultures that came together, many by force through colonization, and that have had to find ways to continue and have had to find ways to not lose all of our origin cultures. So the blending shows up all the time in Caribbean art in the way that the Caribbean people speak where we’ll code switch from one language into the bits of another but still remain so that there are a lot of words in Trinidad in English, for instance, that are French and Spanish. Right in there is a history of who was doing the call medicine. The blending comes naturally. I grew up with a lot of the different cuisines from the Caribbean countries in which my family was living. That's Jamaica, where I and my mother are from, Guyana, where my brother and my father are from, Trinidad and Tobago, where we have so many relatives. Yes, I do cook very well. [laughter]

DN: It had to be true. I would be shocked if you told me you didn't cook.

NH: I tend not to do anything that takes a long while to cook 20 minutes in the mother there. But I do cook very well and often don't use recipes. I will use a recipe if it's something where the proportions are important like a pastry or a cake. But anything else, I will very rarely make the same thing twice. It'll have more or less the same ingredients but there'll be something different. I like experimenting when I have the resources to do so. I haven't always. But experimenting with what flavors might go with what. I realized a few years ago that the way I'm able to do that is because I love food, I have a library of tastes in my head and I can mentally put two together and think, “How would that work? I have a feeling that might be okay,” which is how I learned that cloves in savory food, cloves in meat, ooh, the meat sparkles. Cloves and fried chicken, damn, like in the batter. So yes, I like putting food in my stories. Again, I will often resort to food when I get stuck, like, “Let's have them have a meal.” [laughs] With this one, I especially wanted to invent foods. Part of the way I'm signaling that this is not consensus reality, this is fantasy, is that some of the foods, you would not put those ingredients in food. Just don't dip a stick into a Pitch Lake and white sh*t in the soup. Like, don't do that. [laughter] But that is very much what one of my characters does. I was imagining what that sulfurous flavor might do with food, how it might improve it. Sometimes I look things up from other cultures and imported those. But also, I just love Caribbean food so I get to write about it. Again, I'm using dynamism. I'm using the kind of metaphors and strong imagery that make your own nerve endings fire. Because that's really the only way to describe something like a smell or a taste. I remember the experience of reading Goblin Market as a kid, Christina Rossetti's poem. At that point, most of the fruits that are referenced in there, I had never tasted because I was living in the Caribbean. They were from the British Isles. But I felt I could. In my head, I had an imaginary set of tastes because she described them so well that your own imagination kicks in. Of course, when I finally tasted those fruits, most of them were nothing like I imagined. But I had still enjoyed the poem. I was trying to do that and will try to do that when I write about food. I have sometimes blogged about food and posted how I cook things. Yeah, it's very, very important to me. It's so much easier than writing a novel. [laughter] To make a pot of soup is so much easier than writing a novel. [laughter] Then when you're done, you can eat it.

DN: Yeah. Well, I want to take this notion of blending, of bringing things together and blending them into something more philosophical. Because given that the island is about to be invaded by its original colonizers, it's of vital importance to glean whatever they can from the original time, centuries ago now that they succeeded at liberating themselves and sending the colonizers away. But the story is at the boundary of legend and history. The story of the three witches who caused the invading soldiers to be swallowed in magic tar seem a little like Granny Nanny and her incredible butt-cheek dexterity and redirecting bullets. But Granny Nanny was also a real person, and perhaps there's something real and maybe even strategic and useful within the fantasy to help the people now in fighting back. One of the great pleasures of being with Veycosi is he's tasked with doing just that to wade into the myth through the taking of oral testimony. The question is even asked explicitly in the book, “Was the existence of this world miraculous or simply natural? Was there a difference?” This question makes me think of a couple of things, of my conversation with Adrienne Maree Brown about the relationship between science fiction and activism and organizing that none of what we achieve can happen without first the act of imagining and otherwise, or that famous line of Le Guin's, “I think the imagination is the single most useful tool mankind possesses. It beats the opposable thumb. I can imagine living without my thumbs, but not without my imagination.” Most people seem to think of these two as opposites, fantasy and history, whereas Ursula definitely thought otherwise when she said, “They way one does research into nonexistent history is to tell the story and find out what happened. I believe this isn't very different from what historians of the so-called real world do. Even if we are present at some historic event, do we comprehend it - can we even remember it - until we can tell it as a story? And for events in times or places outside our own experience, we have nothing to go on but the stories other people tell us. Past events exist, after all, only in memory, which is a form of imagination.” She also provocatively connects fantasy with science when she says, “There really is nothing to fear in fantasy unless you are afraid of the freedom of uncertainty. This is why it’s hard for me to imagine that anyone who likes science can dislike fantasy. Both are based so profoundly on the admission of uncertainty, the welcoming acceptance of unanswered questions. Of course the scientist seeks to ask how things are the way they are, not to imagine how they might be otherwise. But are the two operations opposed, or related? We can’t question reality directly, only by questioning our conventions, our belief, our orthodoxy, our construction of reality. All Galileo said, all Darwin said, was, ‘It doesn’t have to be the way we thought it was.’” It feels to me like the gesture in Blackheart Man of bringing fantasy and history together, of traveling to that borderlands between the two and seeing what can be pulled forth to do real material action for liberation now, it feels kindred to this to me. I was wondering what your thoughts are on fantasy and relationship to the so-called real or to the archive or to the historical or to the retrieval of story from within a rupture and an erasure.