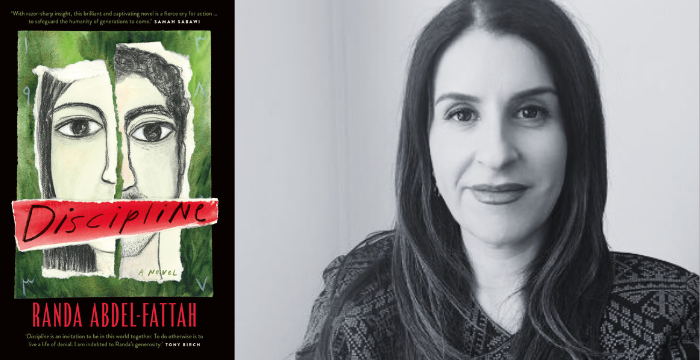

Randa Abdel-Fattah : Discipline

Randa Abdel-Fattah’s new novel Discipline is set in Sydney, Australia in 2021 during Ramadan. Discipline follows two Palestinians there, one in media and one in academia, where each has to confront questions of silence and complicity in their respective fields. As Israel intensifies its bombardment of Gaza, and as an eighteen-year-old student at a local Islamic school is arrested for protesting a university’s investment in an Israeli arms manufacturer—an arrest that results in an Islamophobic moral panic across Australia, our two Palestinian protagonists make very different decisions on how to engage with the power structures within their disciplines and within the country at large. What is the cost of staying and fighting within an organization that wants to silence you? What is the cost of walking way? In addition to being a riveting read on the level of story, Discipline is also a sort of primer on the weaponization of language, particularly liberal rhetoric employed to capture and domesticate radical movements of change.

For the bonus audio archive Randa contributes a reading of excerpts from Chelsea Watego’s “Always Bet on Black (Power): The Fight Against Race.” This joins bonus readings from Dionne Brand, Danez Smith, Isabella Hammad, Natalie Diaz, Omar El Akkad, music from Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and much more. To learn about how to subscribe to the bonus audio and the other potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally here is the BookShop for today.

Transcript

David Naimon: You’re reading a 400-page manuscript. This is your job. But when, 200 pages in, a bunch of clowns mysteriously show up, the plot goes off the rails. It’s your job to fix this manuscript. You’re an agent, or an editor, or a friend of the writer. But using today’s tools, Microsoft Word or Google Docs, you spend half your time fighting the software. You don’t want mail merge or check grammar or to even edit the manuscript. The keyboard keeps showing up and you lose your place in the manuscript. Enter Marginalist, an app for agents, editors, professors, writers, or any reader of long-form text. Marginalist lets you import Word documents, read with the utmost grace, leave comments effortlessly, and then export right back to Word. Marginalist is free to download for Apple devices at the App Store. Or even better, get the first six months of the Pro version free by going to marginalist.app/slash/covers. I’m really excited to share today’s conversation with Randa Abdel-Fattah about her novel Discipline, a book that is about many things, but among them, it is a book deeply about language. I think of the way Omar El Akkad’s book, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, engages with and dismantles liberal rhetorical strategies, strategies that allow one to dodge engagement, to avoid taking risks on behalf of others, and yet at the same time preserve one’s own sense of goodness at the same time. Imagine just such an examination, but dramatized in a novel with characters, diaspora Palestinians in Australia, working within the media and within academia. But another element of this book, of many of Randa’s books, and of Randa as a thinker in the world that I immediately think of is around questions of solidarity and what true solidarity looks like. Solidarity beyond rhetorical gestures, but in the real material world, and how true solidarity, a commitment to it, and through the act of doing it, how it can transform one’s sense of identity, even more, perhaps deepen and enlarge one’s sense of community too. What Randa chose to contribute for the Bonus Audio Archive is just one small example of how Randa moves in the world. She reads from an essay called Always Bet on Black (Power) by the Aboriginal scholar and writer Chelsea Watego, author of Another Day in the Colony. This joins an ever-growing archive of supplemental material from Isabella Hammad reading from the prison writings of Walid Daqqa, to Roger Reeves reading Ghassan Kanafani, from Rabih Alameddine reading the poetry of Pessoa to Zahid Rafiq reading Kafka, from Danez Smith creating writing prompts for us, each paired to a different poem, to a call and response of readings between Sofia Samatar and Kate Zambreno. The bonus audio is only one of many, many things to choose from when you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. You can check everything out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today’s conversation with Randa Abdel-Fattah.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I’m David Naimon, your host. Today’s guest is writer, sociologist, and lawyer Randa Abdel-Fattah. Randa is a lawyer of the Supreme Court of New South Wales and a patron of the Racial Justice Centre, the first community legal service focused on racial justice in Australia. Her doctoral thesis in sociology was published in 2018 as Islamophobia and Everyday Multiculturalism in Australia. She’s a Future Fellow in the Department of Sociology at Macquarie University, where her research areas include Islamophobia, race, Palestine, Arab and Muslim social movements in Australia, solidarity activism, and more. Her book, Coming of Age in the War on Terror, was longlisted for the Stella Prize and shortlisted for the New South Wales Premier’s Literary Award and the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award. She’s published widely with articles in The Guardian, Le Monde, The Sydney Morning Herald, Al Jazeera English, Meanjin, and Overland, among many others. Randa Abdel-Fattah is also a children’s book author. Her debut, Does My Head Look Big in This?, follows a 16-year-old girl who decides to wear the hijab full-time as she navigates the different reactions from family and peers. It won the Australian Book of the Year Award for older children and was adapted into a full-length play. She also created Australia’s first early reader book series focused on diversity and anti-racism and wrote Australia’s first Black-Palestinian picture-storybook collaboration with illustrator Maxine Beneba Clarke called Eleven Words for Love: A Journey Through Arabic Expressions of Love, shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Award and listed as a Children’s Book Council Awards notable book. Her research on Islamophobia from the point of view of the perpetrators led to her young adult book When Michael Met Mina, where she imagined what would happen if two teenagers from opposite sides of an anti-refugee rally met and fell in love, a book that went on to win the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award and the People’s Choice Award. Her other books include Ten Things I Hate About Me and Where the Streets Had a Name, set in Israeli-occupied Bethlehem and winner of the Middle East Outreach Council Young Adult Book of the Year. As if this were not enough, Randa is also the co-host with Sara Saleh of the great podcast 2 Pals & a Pod, where feminist praxis meets decolonial side-eye, where in “each episode, we sit down with thinkers, artists, advocates, and organizers who refuse to be polite in the face of genocide and in a world gaslighting us into silence. We say the unsayable with plenty of receipts, rage, and real tenderness.” So it’s with great anticipation that we welcome Randa Abdel-Fattah to Between the Covers to discuss her electric new novel for adults, out from University of Queensland Press, called Discipline. Nour Haydar for The Guardian says of Discipline, “With visceral detail, Randa Abdel-Fattah captures the pangs of survivor guilt and rage felt by first-generation Australians witnessing the destruction of their homelands while living in 'the empire', and the cost of speaking out against the status quo.” Michael Mohammed Ahmad adds, “While it may sometimes feel as though its characters are fighting a losing battle, the very existence of this book provides hope: all steps towards freedom and justice always begin with reading. For those who seek to sincerely understand the endless obstacles one must face in the body of an Arab, a Palestinian, a Muslim; Discipline is the place to begin.” Finally, Tony Birch says, “Randa Abdel-Fattah is a remarkable writer. With humility and care she asks that we do not turn away from the people of Gaza. Discipline is a novel that reminds us that each story is a shared story, demanding our attention. Discipline is an invitation to be in this world together. To do otherwise is to live a life of denial.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Randa Abdel-Fattah.

Randa Abdel-Fattah: Thank you, David. I am so honored, delighted, and excited about this conversation. It feels almost like a guilty pleasure to have an extended conversation in a world that demands soundbites. So I’m very excited to sit down and speak with you.

DN: Yeah. Very much likewise. So you’re only the fourth Australian writer on the show after Alexis Wright, Nam Le, and Michelle de Kretser. I realized very quickly in preparing for those conversations how different the discourse is there versus here, and how out to sea I was regarding certain things. For instance, the vast differences around Blackness in the U.S. versus Australia. I more had a sense of what I didn’t know rather than feeling sufficiently knowledgeable to be able to talk intelligently within an Australian framing. But in reading Discipline, most of what you portrayed concerning anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia and the silencing of Palestinian voices seemed, in contrast, immediately legible to me in a North American context. But nevertheless, not trusting that this is true, I looked into differences in demographics. For instance, the Arab population in Australia is much bigger proportionally than the U.S., where here roughly 1% of Americans are Arab and in Australia three times as much, where Arabic is the third most spoken language in Australian households. When it comes to the differences between different Palestinian diaspora communities, unlike Chile’s large Palestinian diaspora, which largely came before the Nakba during Ottoman rule, and in the U.S., where the largest wave was after 1967, the Palestinian community in Australia largely came as a result of dispossession by Israel in 1948\. But my question for you comes from the presumption that you know a lot more about what is going on here in the U.S. than we know about what is going on there. I also don’t want to presume that my first impression that the Palestinian experience in Australia translates pretty smoothly to the experience here. “I wonder if there’s anything Australia-specific around the world of Discipline that you would want to highlight as a substantive and important difference, or if there isn’t anything, perhaps something specific about Australia as a country in relationship to Israel and Palestine?”

RAF: Yeah, that’s a great question. It’s a question, I guess, that I haven’t reflected on because, you know, the fish doesn’t notice the water. [laughter] I mean, growing up in Australia as a Palestinian Muslim, living here on stolen land in a settler colony, I think I’m very cognizant of my identity in terms of being the daughter of a dispossessed Palestinian and yet complicit in dispossession here. I think that’s probably one central difference in terms of the community here understanding in a very visceral way what it means to live on stolen land. There is a very, very strong tradition of Black–Palestinian solidarity here in so-called Australia. I think that that has really shaped the way that we have responded to racism here. We see, though, that Australia very much steps in line with the U.S. in terms of foreign policy and in terms of borrowing from the lexicon of racist language and tropes and popular culture and those hegemonic ideas around Muslims and Arabs and Islam. So very much plugged into that global circulation of moral panics and fears and tropes and stereotypes. It’s very much a globalized economy when it comes to the Islamophobia industry. I guess just the specificity of being on stolen land here and the way that we have inherited those imperial and colonial tropes and discourses is something that has shaped our experiences of racism in this colony. But there are very much parallels and overlaps with what is happening in the U.S. I think the U.S. is very much the cautionary tale. The ICE raids in America, I can see things like that happening here very soon, very quickly. We have offshore detention centres storing refugees offshore. We have the discourse around refugees and immigrants as other and as threats, and plugging that now into our resistance against what’s happening in Israel, the genocide there. All of these circulations of ideas and stereotypes and violence, I think, borrow a lot from the example of the U.S.

DN: Well, it feels to me like Australia, at least rhetorically, is way ahead of the United States in terms of acknowledging, as you just did, being on stolen land. I really love the way you open your podcast with this question that you ask to every guest, which I was going to ask you, but you’ve already answered it, which I think maybe is even a testament to the way this has become part of building solidarity and building solidarity across difference too. This is what your co-host said in a recent episode of your podcast to start it: “We live on Indigenous stolen land. We are beneficiaries of settlement, but we are also survivors of Western imperialism and racial capitalism. So we like to ask our guests to not just begin with your origin story or your roots, but also acknowledging and understanding whose land you live, love, fight, and protest on.” It’s something that I feel like probably generates a lot of hard-to-identify but replicating connections when you repeat this over and over again with different people who come on the show, one to the next.

RAF: Yeah, it grounds our positionality. This is a journey that I’ve had to come to, this realization that I am a Palestinian, but I am a settler here on stolen land, and to recalibrate and reconfigure my sense of belonging, my sense of responsibility here. That’s a journey that it’s taken many years to get to. I guess we can talk about this in detail because it intersects with the book and the way that I try to interrogate how multicultural, diverse communities, in particular Arab and Muslim settler communities, how they interact with the state, how they identify in connection with that state, how they respond to the invitation to whiteness, how they yearn and are seduced by the mythologies, and how sometimes they acquiesce to those mythologies about being the most multicultural tolerant society. Meanwhile, we’re living on stolen land. So I really take that very much as an identity project, as a way of orienting myself here. I’m talking to you from Dharug Country, and my children play soccer in a playground a few streets from me, and that soccer field is named after a family who were integral in the stolen generation, who had a farming house just a few streets from mine, where Aboriginal children were stolen from their parents and were placed on these missionaries. So it’s in those banal, mundane spaces of my children’s soccer field in the suburbs that I live in that I am reminded and haunted by this genocidal past and ongoing slow genocide now. To come to that understanding has been liberating. It’s been liberating in terms of how I can figure who I am on this land, my responsibilities, my relationality with Indigenous people, and in our solidarity movements.

DN: Well, definitely, I want to return to this moment. So we’ll put a little bookmark here and return to this question once we’ve talked more about the book. You’ve situated yourself in relationship to the land. Let’s situate this book in relationship to time. When you talk about your own personal trajectory, you’ve cited in different talks certain pivotal events in your life. You say that it was during the Gulf War when you first came into your identity and realization that you were an other, even if you didn’t yet know how to relate that otherness in Australia to others who were also othered. You’ve described 9/11 as the loss of your individuality, suddenly being seen as a racialized collective of Muslims, and how, at the time, your response was, at least initially, to say, “We are not terrorists,” to call for more intercultural dialogue to humanize Muslims. You said in a recent conversation with Mohammed el-Kurd that you now see the impulse that you had then, and also the impulse in some of your earliest books, as a form of self-dehumanization. You began writing Discipline in 2021, and it is set in that year during Ramadan in Sydney. October 7th and its aftermath, you’ve described as paralyzing to you as a writer, but then in 2024, this book poured out of you, even as you had been at the time suspended by your university, perhaps even writing against that censorship. But I was hoping you could talk to us about the importance, if there is one, in keeping it set in 2021\. Did you consider switching it to a post–October 7th book? And what did that debate look like, if there was one? What would have been gained and what would have been lost if you had moved the date? And what is gained and what is lost by keeping it?

RAF: Well, I started writing this book. It was originally called The Occupation. I started writing it around 2020, 2021\. My goal then was really—one of my practices as an academic and as a writer is to try and bridge that gap between the ivory tower of academia and the books that we produce and the articles that we produce that maybe five people will read behind academic journal paywalls, and the closed sort of language and jargon that doesn’t democratize knowledge at all. One of my practices is to always produce fiction, a work of fiction, a creative artistic work, out of the actual academic research. So you mentioned Coming of Age in the War on Terror. Forgive me if this answer is a bit lengthy, but I really want to give the context of why I chose 2021\. So Coming of Age in the War on Terror was the academic book that I produced as a result of my postdoctoral fieldwork with young adults, young teenagers, who have only ever grown up in a world at war on terror, so born around 9/11\. We call them the post-9/11 generation. I wanted to explore their trust relations at school, whether they felt school was a safe space for their political expression, to negotiate and experiment with their political ideas, or whether they felt they were being shut down. I compared Muslim and non-Muslim students, and I did writing workshops across schools in Sydney. One of the consistent themes that I found was the potency of these common-sense hegemonic ideas around Muslims as potential terrorists, as potential danger and threat. I wanted to trace what Stuart Hall calls the practical ideologies. How do these practical ideologies actually filter down into everyday life, into a material force in these people’s lives? One of the people I met was a young student called Bilal. He came up to me after I did the writing workshop. He said, “You know, miss, school used to be the one place that I felt safe.” But then in the context of hysteria around ISIS and so-called jihadi watch schemes in schools and homegrown terrorism, he felt completely censored in his classroom contexts because he felt anything he said as a young Muslim Arab male was going to be construed as somehow leading him on a conveyor belt to terrorism or extremism and radicalization. So he shut down. That was a very familiar testimony by a lot of the students that I spoke to. So I started writing a book that wanted to really draw people into this world, the pressures, the emotional toll that it takes on young people to navigate school systems and securitization of their bodies, their suburbs, their language, their clothing in this environment. In September 2023, I was actually in Philadelphia for the Palestine Writes Literature Festival, and I emailed a publisher with an outline of the book. I said, as a researcher, I know that the war on terror still lingers, but very quietly in the background now. There’s not a lot of noise about what is happening, but the violence is still there and enacted by the state, but very quietly. The spectacle of it has gone. So people, I do feel, are blind to the slow erosion of rights and the slow securitization of young people. “Is there any appetite for a book that explores this?” Because I’d written about 20,000 words. The publisher said, “Look, I’m not quite sure, but go away, keep writing.” So I kept on writing, and then the next month, October 2023, and like you said, I felt paralyzed. I didn’t know. Now everything that I was foreshadowing in the book—I mean, the book opens in the original draft with a young student protesting Elbit Systems in a university and being arrested. When I was writing it, it felt like a foreshadowing of an issue that people weren’t paying attention to, the criminalization of protest, specifically by Palestinians. Now this almost feels anachronistic. If not anachronistic, it feels like it’s such an obvious thing that’s happening now. “How do I write about something that’s unfolding in real time?” “How do I even process it?” Let alone the emotional toll and grief and trauma that we were experiencing and still are. But “how do I write about something when it’s changing so quickly?” And so I put it aside. Then I remembered Toni Morrison’s quote. It came to me looking at a video of a journalist who had used his position to shut down our voices in 2020 and 2021, who was now suddenly, slowly coming on side. I remembered Toni Morrison’s quote about the final solution, that before there is a final solution, there is a second, a third, that it takes many steps to get to that final solution. That really is about urging us to think about accountability, how you don’t get to a livestream genocide without so many people in positions of power having manufactured consent, having used their positions to shut down our voices. So, as you mentioned, I was suspended. I remain suspended 11 months later from my position as a Future Fellow at Macquarie University, and I’m fighting that. I decided that I would write the book, address these issues, but from the point of view of accountability. That meant rewinding it to 2021, the last assault on Gaza, and looking at the way the media and academia were absolutely complicit in silencing our voices. I was very clear in the acknowledgment that this was a book that really didn’t shy away from holding people to account because the violence of silencing us then, I believe, has a causal, a direct causal link to what we are witnessing now.

DN: Yeah. Well, one thing I love about this book is that in addition to it being a compelling and dramatic story in its own right, it’s also a primer on how liberal rhetoric is used, often with a friendly veneer, either to silence or domesticate and capture a radical liberatory thought and speech. Discipline dramatizes in real-life scenarios the mechanisms of how language is employed in the two settings you mentioned, the media and academia. You are particularly qualified, I think, to write such a book because of all the different ways people have tried to silence you. We have two questions for you from others that I want to play together as one. But before I play them, I want to give a long preface to the questions to orient North American listeners to your situation. It will almost be a second introduction as I catch people up to speed on this. When you were on Antoinette Lattouf’s podcast, who herself was taken off the air after she shared on her personal Instagram page a Human Rights Watch post about starvation being used as a tool of war in Gaza, where later the Australian Broadcasting Corporation had to pay a fine to her when their actions were deemed unlawful, in that appearance with her, you talk about some of these things you’ve endured. One of the most visible was the campaign to get your Australian Research Council grant on the history of Arab Muslim Australian social movements revoked, a grant for $870,000, which they ultimately succeeded at doing. Another worth mentioning is what happened at the Bendigo Writers Festival because of the way they employed language, a way that I think speaks to the language you interrogate within Discipline. Two days before the festival, they sent out a code of conduct for participants that one must avoid language or topics considered inflammatory, divisive, or disrespectful, and adhere to an anti-racism policy that conflated anti-Zionism with antisemitism. Speaking to this, you said to The Guardian, “How ironic that they would invite me on a panel called Reckonings, where I’m going to be discussing a book on silencing Palestinians, and then attempt to silence me.” You pull out of the festival, and eventually over 50 people follow you, and the festival doesn’t happen. But the irony doesn’t stop there. After their attempt to silence your book on silencing, the newspaper The Age commissions an essay by you about it, which you wrote and they declined to publish. An essay that begins, “Can you imagine what it would be like to receive death and rape threats at your workplace and your home? To have your work email account hacked and used to sign you up to plastic surgery clinics across Australia and the United States? How about having donations made in your name to the Israeli military with receipts sent to your personal email alongside your phone number and your home address? Can you imagine someone writing your name on the side of a bomb or the president of the Zionist Federation of Australia publicly calling for your workplace to become unsafe for you?” I suspect your redaction of the acknowledgment section of the book, or parts of it, is probably also informed by this climate. Your essay also looks at how the language of the policies that were used to silence you appropriate concepts from First Nations and anti-racism advocacy so that they, on the surface, seem to be doing good things. Lastly, it’s important, I think, to say that there was even a campaign to prevent the publication of this book that we’re talking about today. So our first question for you is from the historian, activist, and writer of novels, short stories, and poems, Tony Birch. The Saturday Paper said of his most recent novel, “Tony Birch’s Women and Children centers on the experience of Aboriginal women. Domestic violence, the inheritance of the stolen generations, class and justice are all concerns of Birch in this tender novel about families, their refusal to accept silence, and their resistance against the systems that oppress them.” So I’m going to play the question from Tony and then introduce and play the second question before you answer. So here's a question from Tony Birch.

Tony Birch: Hi Randa, it’s Tony Birch, your biggest fan. Thank you very much for your work. I actually have a question that I wanted to ask you regarding your writing, particularly over the last couple of years. Obviously, you’ve been under a lot of external pressure and you’ve had a lot of very difficult issues, very emotional issues to deal with. I just wonder how your writing sits with those emotions and those pressures. Does your writing give you any sense of comfort? Does your writing alleviate that pressure, or considering what it is that you write about in the process of doing the work, particularly around Gaza and Palestine, does it in fact bring more pressure? Or maybe, I suppose, the issue there would be greater responsibility to what you’re writing. Thank you again very much for all that you do.

DN: So our second part of this question is from Aviva Tuffield. Aviva is co-founder of the Stella Prize, given annually to an outstanding book by an Australian woman or non-binary writer. She’s past deputy editor of the Australian Book Review. She’s an executive member of the Jewish Council of Australia, which in my amateur attempt to make correspondences between our two countries seems roughly analogous to IfNotNow or Jewish Voice for Peace in the U.S, I think. She’s your publisher at the University of Queensland Press. So here’s part two from Aviva.

Aviva Tuffield: Hello, Randa, and thank you to David for encouraging me to ask a question as the publisher of your latest book, the novel Discipline. We’ve been on quite a journey with this book, Randa, given that its acquisition and publication were the subject of complaints and challenges from the pro-Israel lobby and the right-wing media calling for the book not to be published. I have seen the toll that that targeting takes, and when David said I should ask a question, my first thought was to ask, “How do you keep going?” But perhaps a more insightful question might be, was it at all cathartic to write Discipline or simply enraging, given that your characters have to navigate the racism and complicity of two professions, the media and academia, that you have experienced up close? And as a follow-up question, as someone who has written many books, did anything about the writing and/or audience reception of this particular novel surprise you? Thank you for the opportunity to ask a question.

RAF: I love this. [laughter] It feels like that series This Is Your Life, when someone comes out. This is so special and moving. Two people I just love and admire so much. Aviva used an adjective I wanted to use to answer Tony’s question. It was cathartic. I said before that I felt paralyzed, and there have been many moments that I’ve felt, “I cannot write anymore.” I feel that we’ve come to a point at which we are no longer in an information war about what is happening in Palestine. I know, obviously, that there is the whole war on narrative and access to information. But I spent almost two decades very much as an activist on the front line of organizing media work, and our major obstacle and challenge was always, “How do we get the Palestinian voice and narrative out?” “How do we get people to pay attention?” “How do we mainstream this movement?” “How do we go from 200 people at a protest to 2,000 to 200,000?” “How do we mainstream our language, our political demands?” “How do we get people to pay attention to what is happening?” I think we’ve passed that now. So there have been moments, many moments over the last two years, where I felt everything that has been said has been said. There are only so many different ways that you can try to convince people that genocide is bad. I still haven’t processed that because I feel, as somebody who’s been in this movement for a long time, there is a lot of work that we need to do to process what is happening. There’s no quiet to do that. There’s no time of rest. But this book, writing Discipline, it’s been written in a simple way, but I can say that there is a lot of background research and life experience and lived experience and testimonies that I have drawn on to write this book in an accessible way. To me, it poured out at a time when there was a moment at which that creative paralysis was lifted, and it poured out. It was cathartic. It was fun. It was so much fun to be able to realize that they have taken our voice from the media. We don’t get platforms anymore. They attempted to stop our projects, silenced us and disciplined us in meetings and through lawfare, through media campaigns. But the one thing that they cannot take from us is the ability to satirize, the ability to poke fun and ridicule, and to do that with a contempt for their rancored hypocrisy. So I had so much fun. That, in itself, was my way of claiming some joy, some defiance, and resistance against the oppressive forces that seek to silence us. You know, art has not been spared. Creative spaces have not been spared from the attempts to censor us. As you know, this book, there was a campaign for it not to be published, but it was only because of the solidarity of people like Tony and First Nations authors and diverse authors who supported me and stood in solidarity with me that this book was able to come out. They’ve also asked about what surprised me. It surprised me that it was a book that I didn’t struggle with in the way I have other books. It surprised me in the sense that I had so much fun. It was therapeutic. There were moments at which the book could not keep up with what was happening in my life. So I was literally writing creative chapters on the same day that I was writing legal responses to what was happening to me. In terms of audience, I have been gratified by the fact that particularly young Muslim and Arab journalists and academics have felt seen in this book, their experiences validated.

DN: Well, before we talk about the characters in Discipline, I wanted to spend a minute with the background atmosphere. There are three things that colored the atmosphere of the book for me as a reader. For one, it’s set during Ramadan, which influences the rhythms of this book and the textures of this book. But it’s also set during an upswelling of violence in Gaza. Every character in the book, secular or religious, is on TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter, and having their days punctuated repeatedly by the livestream of horrors in 2021\. Everything good or bad happening in Australia for your Palestinian characters is sort of subsumed in this larger atmosphere of Palestine under attack. The third thing that is also, I think, in a way a background atmosphere, but at the same time it’s also the engine that drives everything that happens in the foreground, is an incident that happens with an 18-year-old student, Nabil, that has become national news and a national debate. Everyone in the book has an opinion on it. I was hoping you could paint for us the scenario of what he does and the subsequent discourse and panic that ensues in Australia around it.

RAF: Nabil Mostafa is an 18-year-old young Muslim Arab male student in his final year of high school, attending an Islamic school. I don’t know if you have Islamic schools in America, but Islamic schools are part of the independent school system, like Catholic schools and religious schools, that still run the curriculum. I attended an Islamic school. I’m very much immersed in that world. My mother was principal of the school. So for me, it was very much about world-building, and we can talk about that. Nabil is part of a group called Weapons of Mass Interruption, which is an activist group. We read through one of the characters, Ashraf, that there has been an occupation of a building at a university, and at that protest against Elbit Systems, so a weapons manufacturing contract with the university. Nabil, as an 18-year-old, his name is revealed. That was very important because if he was a minor, it wouldn’t be revealed. So that puts him, his family, his community, and the school immediately under public scrutiny. He livestreams the occupation. He’s wearing a green headband, a very subversive, cheeky act, with Arabic numerals which gesture to the UN resolution in 1983 on armed struggle. He waves the Hamas flag. Bear in mind this is 2021, so the entirety of Hamas has not yet been a proscribed movement in Australia, just the armed wing part of it was. That was also very important. He is arrested under counterterrorism laws. As a result of that, that’s where the story unfolds.

DN: Well, let’s spend a moment with the question, “Do you condemn Hamas?” that follows every Palestinian in the public sphere. Particularly because you’ve had several incredibly high-profile moments on Australian television that I’ll be sure to include in the resources that go out to supporters. You are unusually adept at handling these rhetorical moves, whether because of your background as a lawyer or simply from all the practice you’ve surely needed to navigate the attacks against you. I don't know. But because of Nabil’s act, this question of Hamas is being posed and answered in different ways by the various characters in your book. For instance, when the journalist Hannah is asked this by a peer at the newspaper, she says, “If you sat with my husband’s family in Gaza, you’d find some are communists, some are anti-Hamas, some are pro-Hamas, some are Fatah, some are Marxist, some are Islamic Jihad, others Salafi. But all share one thing in common. They’re refugees on their own land, living under brutal Israeli occupation and blockade, and they support the right to resist and defend themselves.” But the way Hannah responds is not how everyone answers this question. I’m more interested in what you see this question doing. I have my own theories, but I would like to hear yours. What does this question do rhetorically? What is behind it? What does the question elide? And what do you see as the best ways to avoid the traps that it sets out, often at the beginning of an encounter with someone in the media, but also in this book, also in conversations with colleagues, either in universities or in the newspaper setting?

RAF: Yeah, I think there’s a moment in the book where it re-encapsulates the way that I have arrived at my conclusion about what the work of this question does, what it’s intended to do, which is it’s a trap into policing your thoughts. Because ultimately, if you ask that question to any Palestinian in the diaspora, “Do you support Hamas?” well, I don’t materially support them. What do you mean by support? I don’t send them money. I don’t fund them. I’m not their legal advisor. Ultimately, what they’re asking you is, “What is your moral position on Hamas as a resistance movement?” And that’s immediately a trap because of the way the legal regime works to proscribe moral support and your thoughts and attitudes towards this organization. So now we’re in a situation where you can’t actually answer that without falling into self-incrimination. So instead of answering the question at face value and giving it any legitimacy, it’s about unpacking, like you said, what is it trying to do? And the first thing it’s trying to do is dehumanize you as a Palestinian by forcing you to acquiesce and to surrender and to accept that there is no acceptable way for you to resist occupation and genocide within the confines and expectations of Israel and the Western order. It’s forcing you to surrender because what they’re actually trying to do is to take away your right to say that we can resist violently and we can resist through armed struggle because nonviolent resistance has not been allowed for us. Even a cupcake sale at Sydney University fundraising was disallowed on the grounds that it was antisemitic. A Change.org petition is not going to liberate Palestine. But we can’t have conversations about this in the West because of the way the legal regime works now to discipline, criminalize, and punish this. So it’s ultimately a position where they are forcing you into a corner to try and punish you and silence you.

DN: I should add from an American context that two-thirds of American states have outlawed BDS, another nonviolent approach, and there was not a huge outcry when 6,000 Palestinians were shot during the Great March of Return, another nonviolent activity. But I wanted to add a couple more thoughts about Hamas before we move on, just to hear if it sparks any more thoughts for you. Because this is central, in one respect, to the way you’re dealing with rhetoric and discipline. I agree with Mohammed el-Kurd when he says, “When you go on TV and somebody's asking you, ‘do you condemn Hamas?’, they're not really interested in your political assessment of Hamas. They're interested to see whether or not you fall into the liberal world order, the world order that they have decided to expel Palestinians from. It's not a questionnaire, per se. It's an interrogation. You are spending the interview in cross-examination.” It does feel like it’s a litmus test of whether you are civilized or a barbarian, something not meant to start a conversation or discussion, but maybe to prevent one. Most of the "civilized" people who pose this question, I suspect, would likely say that they are not only against Hamas, but obviously, in their mind, for coexistence and a two-state solution. But I’m also pretty sure that the overwhelming majority of those people haven’t risked anything materially or with regard to their status within their own communities to speak out against settler violence in the West Bank or land theft in the West Bank, which was experiencing one of its worst years in 2023 before October 7th, and which is not ruled by Hamas. That their silence and inaction where Hamas doesn’t exist highlights the bankruptcy of the question as a question, I think. In a counterintuitive way, their rhetoric of coexistence coupled with silence, when a grandmother harvesting olives is being clubbed, or masked vigilantes are lighting an inhabited house on fire, makes the liberal position a vanguard that enables the far right to enact its goal of one Greater Israel. It also surprises me that it rarely comes up that Israel cynically facilitated the growth and financing of Hamas for 20 years with the explicit goal to divide Palestinian opinion. I suspect because it’s easier to activate an anti-Arab, Islamophobic monster in the Western imagination with Hamas than with Israel’s opponent for most of its existence, which was secular and aimed for a secular one-state solution. I think you even said somewhere—push back if I’m getting the language wrong—but that Fatah was a liability for Israel and Hamas an asset. But I wondered if this sparks any more thoughts about this question that peppers Discipline as we move through the narrative.

RAF: Absolutely. I mean, there’s a way that you respond to that, that you can recite all these facts and logical arguments. There’s no Hamas in the West Bank. There was no Hamas before the ’80s. Like you said, it’s not a question of debate anymore. It’s about the politics of condemnation. We’ve been on this road before with the War on Terror. It was, “Do you condemn terrorism?” “Do you condemn Al-Qaeda?” Then, “Do you condemn ISIS?” And it was always about forcing you to prove your humanity, forcing you to prove that you are not okay with violence. So the presumption was that you need to be civilized, that you need to prove your civilization or credentials to be able to speak, to be able to advocate. So the racist pretext of this question is what I and others are now refusing to engage with and refusing to take at face value, refusing to dignify it with a logical rebuttal. It’s like, for some funny reason, a conversation between the sword and the neck. It is impossible to have a rational conversation about this because, as Mohammed el-Kurd said, that is not the goal. That is not the aim. What you said sparked my memory that this is about plugging into that larger discourse of Islamophobia, that larger civilizing mission that is always the alibi of Israel. Because if you can just characterize us and caricature us as the terrorists in opposition to Israel and plug into that Islamophobic economy, then you are again playing in that politics of condemnation. So for me, it’s just about refusing it. Hence, we don’t get the interviews anymore because we don’t play that game. There are those who still play that game. But I think that we are at a point now where we should not indulge it at all, and we should shut it down. We don’t debate these things.

DN: Well, I was hoping we could hear a short paragraph that lists one character, Jamal’s experience, that I was hoping you’d read, and then I could ask a question after it.

[Randa Abdel-Fattah reads from Discipline]

DN: The reason why I wanted you to read it is that I think it’s noteworthy that 18-year-old Nabil, who doesn’t have Jamal’s experiences of being from Gaza and still also having family there, his politics change when he returns to Australia having visited relatives in a Lebanese refugee camp. A lot of people who go and see come back changed, where suddenly rhetorical games are seen for just that, because you can’t really unsee or narrativize away what you’ve seen. But thinking of the way Palestinians as a whole get reduced to Hamas and projected upon in this civilizing narrative that you allude to, I notice that this is happening to Nabil too, and even to his Islamic school by association. I suspect it isn’t a coincidence that we never hear him speak in the book, that he isn’t a significant character. Similarly, Jamal, a major secondary character who’s deeply connected to the two main characters—one, he’s the partner of Hannah, the journalist, a Palestinian journalist at a major Australian paper; two, he’s the PhD student of Ashraf, the Palestinian working in an Australian university. Jamal, who, as we just heard, is both from Gaza and still has family in Gaza under fire, his insistence on action now is seen as reckless and lacking nuance, not as possibly a well-thought-out political position. So thinking about these two men, I think of how some of your research focuses on the way Muslim and Arab men in particular are portrayed in Western societies. I guess I would love to hear a little bit more, both why you would focus on men and to what end you would focus on them.

RAF: Yeah, it was a very deliberate choice for Nabil not to have a single word uttered, for him to be spoken about and written about. Again, this book has come out through my own research and lived experiences throughout the War on Terror, throughout media sensationalism and headlines and political discourse and campaigns against Muslim communities, but in particular Muslim male youth. The book, centering on the Islamic school, actually mobilizes a few stories and headlines. It’s not referred to in the book, but I know that they’ve happened. So it’s very much grounded in what these communities have endured. There were two incidents in 2017 where there was hysteria about so-called jihadi schemes and junior jihadis and Gen Y jihadis in schools in Sydney. Massive political media campaigns mobilized to attach these loose and mobile racial summaries about young Muslim male youth. Sara Ahmed, in her book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, which is an incredible book and one that I’ve used very much in my academic work, talks about emotions circulating within society and sticky signs. So I conceptualized young Muslim male bodies as Velcro bodies. These signs of terrorist, as danger, as threat, stick to their beards, stick to their clothes, stick to their accents, their language, their suburbs. That’s what’s happened to Nabil. He doesn’t get to say a thing. He’s just covered in Velcro and stuck with people’s assumptions and presumptions about him, from his teachers to his peers to the media to the journalists to politicians. So that was very much a deliberate choice. There were two incidents in Sydney schools where there was a group of young Muslim boys at one school, Hurstville Boys, who at an award ceremony, rather than shake hands with the female teacher who was giving them the award, put their hand on their chest as a sign of respect. Australia went nuts. There were even calls by the education minister to check if this breached anti-discrimination laws. There were calls that this would put them on the path to radicalization. We never heard from those students directly. We never heard from those boys. Likewise, at Epping Boys, there was hysteria about the prayer hall there, young male students using a classroom for praying on Fridays, about that being a breeding ground for recruiting young people to ISIS. The school was encircled, and I know this because I interviewed some of the schools, by journalists, and I use this in the book, who would stake out the school, the routes that students took to arrive at school, and then try and ambush students on their way, and the clever ways that the kids would try to circumvent their traditional routes to avoid these journalists. So these are real stories, young people’s lives. The material impact of this global circulation of dangerous and inflammatory rhetoric about them has a material impact on their lives. Young boys in particular, young males—even though most Islamophobic incidents are experienced by hijabi Muslim women, we do tend to forget how the figure of the Muslim terrorist is embodied in the figure of the Muslim male. Another point, though, about Jamal. I recount that history, that chronology of flashpoints of death in his life. This is a very familiar story for all of us. The green screen of our lives is a livestream genocide. But even before this genocide, the green screen of our lives was this ongoing violent occupation and constant stories of this person died, this person’s farm and olive groves have been destroyed, my cousin had a heart attack in his olive groves as settlers were trying to harass him. These are just stories that are in the background of our lives. Yet we have to show up at work, do the water-cooler talk, perform in these banal situations. Jamal is a perfect example of somebody who has to show up and play this liberal game of ignoring empire, even though it reaches deep into his life on an everyday basis. So I really wanted to show how much trauma is involved in that.

DN: Well, we have two questions for you, two different questions about the relationship of politics and ideology to art and the creative. The first is from human rights lawyer, poet, novelist, and co-host of the podcast 2 Pals & a Pod, co-hosted with Randa Abdel-Fattah, Sara Saleh. She co-edited with Abdel-Fattah the anthology Arab, Australian, Other: Stories on Race and Identity. The conversation describes her poetry collection, The Flirtation of Girls, as follows: “A rich collection filled with anger, sorrow, beauty, attitude, wit, and humor. Saleh’s gaze is unflinching. In her prose and her poetry, she renders unique and memorable the ways people resist, transcend, adapt, make the best of things, compromise, endure, lose hope and faith—and sometimes become something other than they might have been. Saleh’s poetry and prose are urgent tributes to remembering.” So here’s a question for you from Sara.

Sara Saleh: Hi, Randa. My name is Sara Saleh. I need you to know that I love your work. You have sustained me. You have shaped canon here, shaped canon and community. I want to take this opportunity to ask you, Randa, you write at the intersection of art and activism. Feel free to push back against that framing or use of the word activism. I know it’s loaded for writers, and especially those of us from systemically and historically excluded backgrounds. But look, I use that as a shorthand for your refusal to separate aesthetics and ethics. “How do you protect your creative integrity when your art is constantly politicized and yet must also serve political truth?” And as a fun little follow-up, because I know how important it is to you for us to insist on life, on tenderness and imagination amid destruction, “If your life had a title, Randa, what would it be, and who would play you in the movie?”

RAF: That’s so cute. [laughs] There’s this beautiful poem that really sort of came after the fact for me, because I’ve never separated my art from my politics, from my insurgent spirit. I’ve used all my books as unapologetically political acts. It’s a poem out of Gaza: “In order for me to write poetry that is not political, I must hear the birds sing, and in order for me to hear the birds sing, the warplanes must stop.” I’m paraphrasing that, but that hits me every single time I hear it. Because the demand that we separate our politics from our art is such a dehumanizing expectation. It is an expectation that is just so self-idealized and indulgent, and this hubris of thinking that this scholasticide and genocide and ecocide and repricide that lives every single minute in our lives in the background can somehow be severed from artistic and creative expression. It is in our DNA. It is part of who we are, that resistance, that acknowledgment, that attempt to create something beautiful out of these ruins, and to also attempt to agitate and push people to think about the way that they live in the world. So I’m unapologetic about that. There’s this beautiful wordplay that Maytha Alhassen uses about witness. She calls it “withness.” So it’s empathy that takes action. This is something that I was thinking about in crafting the character of Ashraf. What does it mean to actually be in empathy with somebody and bear witness to their trauma and pain? Too often, particularly with liberals, we see them pretend and posture as bearing witness to our grief, as being supportive, but it’s all performance because it never, ever translates into actual action by them. So that is a political motivation for me in writing this book. What does it mean to be an ally, to be in solidarity, to be a colleague, to be a peer, and to do more than just passively witness what we are enduring? What responsibilities does that witness invoke? A title for my book? Multitasking. [laughter]

DN: Multitasking.

RAF: Yes. Who would I get to play the character? Oh, I’ve played this game with Sara before. I said Angelina Jolie if I had a facelift. [laughter] She’s got the long hair and she’s a social justice warrior.

DN: Right. Okay, so our second question takes Sara’s question into the realm of processing craft and also, I think, serves as a first step to talking about our two main characters. So this question is from past Between the Covers guest Michelle de Kretser. She came on the show to discuss her book Theory & Practice, winner of the Stella Prize. The Guardian calls Theory & Practice “a form-melding book contending with colonialism, the disharmony that can arise between our purported ideals and how we live, the depths of jealousy and shame, and motherhood and the maternal figures who shape us. It is also an inquiry into what fiction can look like and what it can achieve.” So here’s a question for you from Michelle.

Michelle de Kretser: Hi, Randa. Congratulations on this incredibly powerful and timely novel. My question has to do with your wonderful protagonists. When you were thinking about writing this novel, did you have in mind various positions that people adopt in relation to political conflict and power, and then did you craft two characters who would plausibly adopt two of those different positions? Or did you begin by thinking about characters, and as your two protagonists developed, it became clear that their dispositions and their circumstances would lead them to adopt different positions? So I guess, in short, I'm asking, did you start with the politics and that led to the people, or was it the other way around? Thanks, Randa.

RAF: It was both, depending on the character. I have to say that in terms of my craft, I’m not the writer who plots out and plans out characters and scenes from start to finish and then starts writing. It takes me longer, but I enjoy the actual process of being surprised by my writing, or where it takes me, and figuring out my characters as I go along. With certain characters, such as [Lee], who is a university manager, and Barnaby, the politics was clear for me. They were almost, I would say, the archetypical progressives within the university who maintain the status quo and leverage diversity, equity, and inclusion in order to silence and suppress diverse people with whom they disagree. So for me, the characters followed the politics there. I had a lot of fun writing them. Ashraf and Hannah, no. It was more about developing the characters as I went along and discovering how they would respond to situations as I wrote.

DN: Well, there are other, less public ways that Palestinians are silenced than the ways that we mentioned in introducing you earlier, and the public ways that you were silenced. For instance, you’ve spoken elsewhere about how you used to be regularly invited to schools, and your books for children and young adults were part of school curricula before October 7th. Then suddenly, schools claiming that they had scheduling issues or problems with their budget, where, as a response, you revealed the lie by responding that you would come for free and that you would do a tour at no cost to any school that would have you, but to no avail. In the United States, two of the five finalists for the National Book Award in Poetry last year were Palestinian, Fady Joudah and Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, with Lena going on to win the award. But prior to her winning, NPR, or National Public Radio, invited the two of them on to speak about their books together, both books that engage directly with the genocide. But afterwards, when the episode aired, Lena tweeted that both of them said the word genocide numerous times in the conversation, but NPR actually went into their sentences and removed every instance. That they couldn’t even speak about their own people’s situation and their art about it with their own chosen language in a show supposedly about that art and the award that they were getting for it. This makes me think of our two Palestinian protagonists. Hannah, the journalist at a major Australian paper, they want to use her as their only person of color to get stories. In the stories she writes, she generally gets to review any edits being made to them, except when she writes on Palestine, where they often chaperone her, wanting her stories to be co-written, running other stories alongside hers that two-side her story, putting occupation in "removing" the word apartheid without her consultation. This is all fraught because she’s also making meaningful connections with people where it’s vital for them to be represented in the way that they themselves want to be represented, so she’s beholden to people in this regard. Then Ashraf in the academy, who has more fully internalized the white view of him, who corrals and silences and neutralizes students working under him, namely Jamal, by arguing one needs to be more strategic, one needs to be more patient, and to be aware of how you’re being perceived. You’ve said that you’ve known many Ashrafs in your life, a lot of them either in your own family or in your community, people seduced by liberal multicultural society and the promise that they can go up the ladder if they play by the rules and carve out a safe space for themselves. In your conversation at The Wheeler Centre, you say that you didn’t write him with contempt, but at other times you’ve said you did write him with contempt. Both your protagonists are grappling with the white gaze to a degree. I think Hannah will notice that voice in her and debate it and has a sense of internal sovereignty, but Ashraf feels like he’s been more fully colonized by it. I was hoping you would read something from Ashraf’s point of view, far from your point of view, and then we could speak about it more, and about choosing these two protagonists, not just one in media and one in the academy, but also two people who are in two very different places in relationship to the project of Australia and how they see themselves situated in relationship to the project of Australia.

RAF: So he’s watching an interview, a news interview, with an academic from a university, a Palestinian academic on ABC News. The interviewee, the Palestinian, has used the word intifada, and this is his response. Can I just preface this with a cheeky story?

DN: Yeah.

RAF: I can give you the cheeky story. So in 2021, I appeared on ABC national television’s program Q+A. It’s since been axed. I think there’s a direct correlation with a post-Gaza news world for that reason. But it was the one space that we had where we could get a national audience to talk about these issues. I used the word apartheid. I didn't know then that the ABC had an internal memo to its journalists that they were not allowed to use the word apartheid because they said that it was too important and specific to South Africa. The journalist, the host, pushed back and he said to me, "Whoa, the Human Rights Watch report says Israel practices a form of apartheid," not that it's an apartheid state, as if you can be half pregnant. [laughter] So this was my cheeky way of getting revenge on him. [laughter]

DN: Oh my God.

RAF: The interview was a train wreck. While Ashraf sympathised with Lena having to answer the usual “do you condemn” questions, he was disappointed that she hadn't taken the opportunity to speak to her audience on their terms. The ABC audience wanted something they could sigh about at the water cooler. They weren't interested in Lena lecturing them about settler colonialism and racism. It was like this whenever a Palestinian advocate was interviewed. They displayed remarkable naivety in presuming that audiences were interested in Balfour or Oslo when, and he could be confident given the number of students he'd taught in his academic career, most people didn't even know the history or politics of this country, let alone know or care for the history and political machinations of another. As if operating with such delusion was not bad enough, these advocates and spokespeople also tended to present as always angry, rigid, and uncompromising, thus reinforcing the very stereotypes that prevented people from sympathising with them. They missed the precious opportunity to use the time and platform they were so rarely afforded to get people on their side. Lena was a classic case in point. She was defensive, her responses were inflected with aggression. “Why are you asking me how settlers feel?” And she was being dangerously intransigent in her refusal to condemn Palestinian violence. Even though the violence was retaliatory, yes, he knew that as an Arab and as somebody who had read more books on Israel and Palestine in one week than this news anchor probably had in his lifetime, Ashraf also knew that nobody, least of all the mainstream media and its consumers, were interested in causes over effects. Lena had well and truly messed up by insisting on historical context and structural explanations instead of presenting the only thing that might move a middle-aged white audience, trauma.

DN: We've been listening to Randa Abdel-Fattah reading from her latest book, Discipline. So talk to us about having two protagonists, not just in two realms, two realms that marshal language in a different way, but also being in such different relationships to Australia, I think, and to how they situate themselves as Palestinians in Australia. I'll just add on to that. What is it like to write the voice of this major character, Ashraf, who is speaking an analysis that is so polar opposite of your own?

RAF: Again, it was remarkably, I wouldn't say easy, but he poured out of me because it's a positionality that I'm so familiar with. It's a positionality that I would say I adopted when I first started my activism in a post-9/11 world. I was in university working as the media liaison officer, the very first one in Australia, actually, at the Islamic Council of Victoria. We were positioning ourselves from a point of view of absolute panic, panic that people misunderstood us, panic that if only people could see us as articulate, as calm, as not angry, as not dangerous, as not a threat, in opposition to all those stereotypes that were circulating and being peddled against us, then they would listen to us. Then they would move on to actually engage with us about what it is that we cared about, what our struggle was about. There was a positionality like Ashraf of just fear that the way that we speak is part of the problem. Therefore, if we just adjust our tone, perform a certain civility, appease white optics and white gaze and adopt that civilising posture, then they will listen to us, then they will accept us. Like you said in that introduction, many uncles like this. It's very much a generational thing as well. A point at which you realise, and many of the uncles haven't in that generation, that you are never going to be invited to whiteness. Your proximity is never going to save you. Ashraf has not figured that out yet. He has not figured out that it doesn't matter how Lena speaks in that interview, her positionality as a Palestinian is already marked as suspicious, and she's already working against an establishment media that does not want to hear or accept her political language or her sovereignty in her demands to speak on her own terms. So it's that constant compromise that he makes that I try to elucidate in that passage. I've had people come up to me after interviews where they've said, “It's so amazing that you didn't lose your temper. You know, I would have lost my temper in that interview. It's so good that you kept your cool.” Like the Erin Molan interview that went viral after October 7, where she was asking me to condemn. So many people in the community were in so much praise of me, not because of the substance of what I said, but because it was so good that I didn't lose my cool, that I maintained my patience throughout that. I would push back and say, but what if I had? What if I had shown my anger and rage? I understand that there is a cost to that. But we need to normalise our anger and rage. But there is an understanding that your emotions are embedded in these political and power relations, and you don't have the right to emotion or anger and rage. This is why Ashraf is the least liberated character in the book, because he will not let go of the false promises of the liberal multicultural state that only accepts him if it suits their diversity agenda.

DN: What's interesting about that exchange that went viral that you mentioned is you not losing your cool. I understand your argument for that shouldn't be why you're praised, but what was so interesting about it is you not losing your cool made the interviewer keep raising her volume, making her gestures more staccato and sort of intense. She becomes more and more unmoored. I think it's an attempt to get you to lose your cool, or at least partially, like a way to try to make that moment happen. “See, Randa isn't a sober guest. She's harboring rageful feelings.” But it ended up being, maybe as a side product of you keeping your cool, an interviewer who completely lost theirs.

RAF: I was very, very cognizant of that dynamic, that the calmer I was, the more hysterical she looked, the more unhinged, and she would take her mask off first. I was also very cognizant of the fact that it wasn't live, so I knew that every single thing I said or did would be edited, and I didn't trust them at all. So there were so many things going through my mind in that exchange.

DN: Well, after I read Omar El-Akkad’s latest book and interviewed him for the show, a book that, like yours, deals with liberal rhetoric, as well as dealing with an open letter that he was involved in regarding the Giller Prize in Canada and its sponsorship with Scotiabank, which is a major investor in Elbit, the maker of Israeli drones, I wondered why no one had ever asked our book festival, the Portland Book Festival, to drop their bank sponsor, Wells Fargo, that is deeply invested in and profiting off of death in Palestine. So I reached out to Omar in the early summer, also because he had recently joined the Board of Literary Arts that puts on this festival. He had confessed to me that he hadn’t been there long enough to really orient himself yet to any of these questions of funding, but that he supported this divestment ask. But he also warned me that if I wrote an open letter, that no matter how non-confrontational it was, no matter how gently I framed it, no matter how friendly the tone, that they would likely respond to it nevertheless as an attack. That turned out to be true once it was published with recognizable national and international names—Robert Macfarlane, Naomi Klein, Solmaz Sharif, Nikky Finney, Viet Thanh Nguyen—but more importantly, many local writers from here: Omar, Joe Sacco, Lidia Yuknavitch, Walidah Imarisha, a letter that wasn’t even threatening anything. It wasn’t calling for a boycott, but was just asking them, prior to any sponsor announcement, not to move forward this year with Wells Fargo and telling them why. In my long meeting with Literary Arts, after they did move forward with Wells Fargo in the face of the letter, not only was almost nothing said in that meeting with regard to Palestine and a concern for Palestine, the entire conversation was framing themselves as the victim and then telling me how the open letter had prevented them from us actually getting what we want. That we had done something tactically stupid because they had to be concerned now about donor flight. Because of that, they would hire a PR firm instead of saying anything meaningful because of this. You might get the impression from this part of their argument that we couldn’t understand the impossible position we had put them in, but that the subtext is that if we hadn’t put them in this impossible position tactically, then morally they would have been on board. But he then spent the rest of the time talking about all the reasons, not tactically but on the merits, that he didn’t agree with the ask at all. That all money was dirty, as if that meant all money was equally dirty. That having Alaska Airlines as a sponsor is the same as having this bank seeking out ways to extract wealth from death all over the world. That they shouldn’t be judged on their funding, but only on their programming. That they were taking money away from Wells Fargo and putting it to good use. That Wells Fargo is more than an investor in the global arms trade, which is true. They have shunted Black and brown homeowners into subprime mortgages. They’re singled out as one of the worst banks in the world for accelerating fossil fuel projects globally. They invest in surveillance technologies that ICE is using to snatch people off the streets of Portland and around the country. I bring this up because Hannah has a colleague, Peter, who frequently ignores her critiques and dismisses her concerns. There’s a point in the book where she realizes, like a light bulb goes off for Hannah, that he isn’t doing any of this out of malevolence. That he was so earnest, so self-idealizing, so sure of his worldview, that he just didn’t register her dissent on intellectual terms, but rather as a grievance of identity. Peter believed in what she called the liberal bullshit project of objectivity, balance, and neutrality, and that he believed that he represented these things as a default position. There’s one point in the book where Hannah signs an open letter, which doesn’t violate the paper’s guidelines around what she is allowed to do. Her boss does a double move that reminds me of the double move of Literary Arts to me. At one and the same time, he says, “I support your right to sign this. I believe in free speech.” Yet he also says, “If you don’t remove your name, it will influence what stories we give you going forward.” The crime in Literary Arts’ eyes, I think, was similar to Hannah’s boss’s. I think that we went public versus continuing to have meetings behind the scenes as we had done prior to the open letter. But Omar assured me that what had now become a regular topic of board meetings because of the open letter would have never reached the level of the board had we just had more listening sessions. I don’t know if this is even a question, but I wondered if it sparked anything for you about the centering of dialogue and listening over material change, or liberal rhetoric used to capture and subdue movements of structural change. Certainly. I mean, Ashraf is very deeply invested in this capturing, neutralizing, and neutering of any disruption within the academy. But this experience that I had really felt like it was in conversation with something you were exploring in Discipline.

RAF: It’s that whole argument about—and it comes from as well the Muslim and Arab community, the establishment guard—it came out particularly at the time of the elections, that you need to be strategic in the way that you present your demands. You need to play the game of realpolitik, the Arabic word siyasa, be more politically savvy about how you do things. Ask in more subtle ways, strategic ways, as if power is going to relinquish if we ask politely. So this is never a good-faith debate, because we have never seen any gesture of interest in our demands. It’s always been about how to manage, discipline, neuter, pacify us, so that we think that we’re making a difference, so that we think that we’re engaged in debate. It’s all a distraction, as Toni Morrison said. It is so critical in the racial project to make people think that they are affecting any difference, but at the same time, they’re just on that treadmill. So we’ve come to a point now, post-October 2023, in a time of genocide, where all of those masks have fallen off. We understand the game now that’s being played. I think that many institutions have revealed that it doesn’t even matter if you ask politely. You’re not allowed to ask at all. The idea that you’re going to be allowed to debate anymore—that liberal veneer has been removed. It’s not something that we can even leverage anymore. It’s now coercive repression. We’ve moved into that. So don’t ask. Don’t bring it up. This is reflected in academia and the media and arts institutions as well. But in the book, yes, absolutely, I’m gesturing to how we got to this point where someone like Ashraf emailing an open letter now, I think, would be grounds for dismissal. I mean, actually, I have an incident in the book where he sends an all-staff email asking people to sign on to an open letter. Then very soon after, the executive dean removes the ability to send all-staff emails. Well, that actually happened to me in 2021\. Yeah. So it was to remove the ability to speak to your colleagues in that setting. It was to shuttle us and shepherd us into the most marginal spaces. So we will allow you to speak, but as long as it’s on the margins. We will not give you that platform. It was a form of silencing and ostracization and marginalizing of our voices. So, yeah, absolutely, I really identify with that story that you said. “How dare you bring this up with us?” And actually, that’s why we, as feminists, talk about how mainstream white feminist concepts and frameworks need to be mapped onto what is happening. Like DARVO is something that we are experiencing in the Palestinian movement every single day. You know, deny, attack, reverse victim and offender. It is constant, the gaslighting. You know, “How dare you make me feel bad about genocide? How dare you make me feel bad about our weapons contracts? How dare you insinuate and imply that this is for some nefarious reason? You know, we’re doing good work here.” How dare you subject us to constant processes and demands on our time and effort and resources to have to deal with what you’re doing? We get that all the time, the complaints. We’re made to feel, “If you just used better language, if you just managed your social media in a more savvy way, then we wouldn’t have to deal with these constant complaints.” So it’s reverse victim, reverse victim offender. That is a classic part of DARVO. It’s a form of violence.

DN: What was the name of the guest that you had on 2 Pals & a Pod that that was the focus? It was about feminist praxis.

RAF: Amani Haydar.

DN: Yeah.

RAF: Yeah. Amani Haydar, whose work has been really instrumental in this colony. Her father murdered her mother, and she has been a really critical voice here in problematizing white mainstream feminism and talking about how it needs to be anti-colonial and anti-racist, and to map state violence, state-sponsored violence, and colonial imperial violence, and to trace the effects of that on interpersonal violence. That maps onto the way that everything that we do in this space is pathologized. It’s an individual problem. So you’re bringing up an individual grievance. Fanon is probably the best reference point here, in that we’re talking about structural violence, not individual pathologies here.

DN: Well, we have a question for you about the portrayal of Palestinians that I want to use as also an entryway to talking about that more largely. What strikes me about this book is that even on the first page, where secular Ashraf is talking to his newly religious ex-wife on the phone, Australia to Yemen, his ex-wife who has forgotten to cover her hair because of their established familiarity, we are already in a varied world of difference. Ashraf even has brief, and I would say pretty rare moments in this book that I love, like when his ex says, “How do we raise our girls in a society that is hyper-sexualized, hyper-consumerist, that worships me culture and materialism?” And he answers, “There’s a shopping mall in the clock tower of Mecca.” I just love that moment of complex difference within your portrayal of Palestinians. But all in all, in your approach, it makes me think of your book Eleven Words for Love, as there are innumerable ways Palestinians are Palestinians in the book. So our next question for you is from the Palestinian playwright, poet, and scholar, Samah Sabawi. Her memoir, Cactus Pear for My Beloved, a Gaza family story, was a finalist for the Stella Prize. In its judges’ citation, they said, “Spare, gracious prose delivers Gaza not as a barren battlefield, but a people, proud and human and persisting. ‘How does love triumph over a wall,’ a character asks Samah’s father. Stories like this surely form part of the answer.” Here’s a question for you from Samah.