Rob Macaisa Colgate : Hardly Creatures & My Love is Water

Today’s conversation with Rob Macaisa Colgate is about two books, his poetry collection Hardly Creatures and his verse drama My Love is Water. You could say these two books are approaching the same questions, but from opposite, if complementary vantage points. Questions of care and disability, of accessibility and community, of Filipino-American identity and the afterlives of colonialism, of queerness and its intersections with race, of selfhood in relation to psychiatric medications, of cross-species solidarity, of questions of language and form, freedom and love and much more. We explore a Crip Mad Poetics and Disability theory in relation to the syntax of the sentence, the body of the poem, and in relation to the world-at-large.

For the bonus audio Rob walks us through how he uses Google spreadsheets as a compositional tool. Reading down several rows of poetry drafts, cell by cell—cells full of recognizable lines of poetry, spontaneous asides, open questions, screenshots and more—he shows us how this process leads to the published poems we hear today. This joins an immense and ever-growing archive of bonus material, with contributions from everyone from Johanna Hedva and adrienne maree brown, to Layli Long Soldier and Victoria Chang. You can learn how to subscribe and about the other potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter at the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today’s conversation.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you by Claire Jia's Wanting, a searing debut novel of envy and longing across three lives. Heralded as a dazzling portrait of both modern China and the unrelenting ambitions of the human heart by Belinda Huijuan Tang, Wanting moves through girlhood memories and karaoke afternoons in Xidan Square, aspirational YouTube channels and billboard ads, and private hotel rendezvous and secret WeChat messages. It is a love letter to friendship, a powder keg of impossible interwoven desires, and a siren song that prompts readers to consider why, even as it destroys us, we always seem to want more. Wanting is available now from Tin House. I'm excited to share today's episode partially because, having done roughly 300 conversations on the show, it becomes rarer over time that a conversation covers entirely new ground. I feel like there are multiple elements of today's conversation, and also of Rob Macaisa Colgate's work in general, that do this, that contribute something entirely new to the collective reservoir of thought on the show. In that spirit, another thing that is unusual is Rob's contribution to the Bonus Audio Archive. As you'll learn in the main conversation, Rob uses spreadsheets—the Google Sheets app—as a way to compose poems. In the bonus audio, he walks us through how he does this and then reads down whole rows of cells for several poetry drafts that later become poems in his latest collection. These cells contain recognizable lines of poetry alongside asides, open questions, screenshots, and more. He talks to us as he reads down these rows about how this process works compositionally. This joins a wealth of material in the ever-growing Bonus Audio Archive with contributions from everyone from Kaveh Akbar to Nikky Finney to Layli Long Soldier to Jorie Graham. The bonus audio is only one possible thing to choose from when you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. Regardless of what you choose—access to the bonus audio, rare collectibles, the Tin House Early Reader subscription, or something else—every supporter gets access to the robust resource emails with each and every episode, and every supporter is invited to join our collective brainstorm of who to invite on the show going forward. You can check it all out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today’s episode with Rob Macaisa Colgate.

[Intro Music]

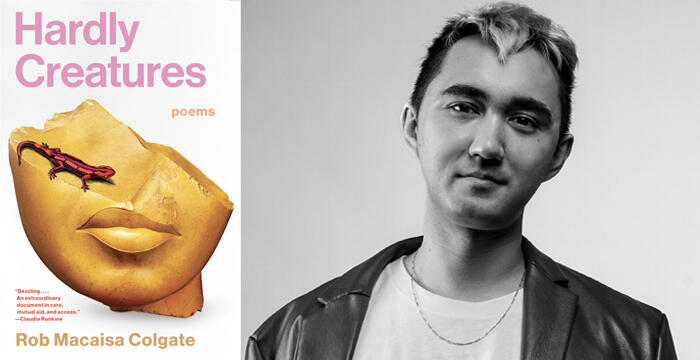

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I’m David Naimon, your host. Today’s guest is the poet and playwright Rob Macaisa Colgate. Colgate studied psychology at Yale, received an MFA in Poetry and Critical Disability Studies from the New Writers Project at UT Austin. While there, he garnered a Fulbright scholarship to be a visiting scholar in poetry at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Disability Studies, and became the inaugural Poet-in-Residence at Toronto’s Tangled Art + Disability Gallery, a gallery innovating bold, new ways to experience and access art. Colgate’s poems have appeared widely, from the New England Review to the American Poetry Review to the Best New Poets Anthology. They are also managing poetry editor for Foglifter, a biannual journal created by and for queer and trans writers and readers. In 2024, Colgate was awarded a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship. In 2025, an NEA Poetry Fellowship, two accolades which only scratch the surface of their fellowships and scholarships, whether from Tin House, Lambda Literary, or MacDowell. They're here today to talk about two books of theirs, both debuts and both out this spring: the verse drama My Love is Water from Ugly Duckling Presse, and the poetry collection Hardly Creatures from Tin House. Chad Bennett says of Colgate’s debut verse drama, “Rob Macaisa Colgate’s expertly choreographed My Love is Water stages a Boystown house party you won’t soon forget, populated by an unlikely mix of Filipina exchange nurses and gay Grindr friends. At the center of this theatrical space of excess and enlightenment, our host, the recently dumped Danilo, enacts a messy and moving meditation on care, disability, and queerness; on the cruel promises of empire; and, especially, on outsized and lopsided love.” Felicia Zamora adds, “Full of spectral visitors, longing, wild embodiments of verse, celestial navigations, and haunting echoes of a former lover, My Love is Water is an entranced fever-dream of what lurks inside loss, selfhood, and the mind. Deliciously strange, deliciously heart wrenching—this book radiates pure magic.” Here are some thoughts on Colgate’s debut poetry collection from some of today’s luminary poets. Chen Chen says of Hardly Creatures, “Never before have I experienced a book of poems that cares this firmly and boldly, this inventively and fully for its communities and for its reader… I felt my entire world shift.” Past Between the Covers guest Claudia Rankine adds, “A collection unlike any I have ever encountered before. Part primer, part activated art space, part personal/community inventory, part lyric collaboration with mental illness—this book activates new zones between disability studies and poetry, allowing readers spaces for rest, recognition, and reimagination inside its dazzling and varied forms. An extraordinary document in care, mutual aid, and access.” Finally, poet and critic Stephanie Burt for The New York Times: “Colgate’s poems attend, delightfully and exceptionally, to extraordinary bodies and to shared physical needs… Better yet, they attend to the joys, the constraints and the weirdness of new and old poetic forms. Colgate can roll accounts of his life into ghazals, stack them in abecedarians, shuffle them into sestinas or drop into a cascade of intimate truths, much in the manner of C.D. Wright. ‘I am not brilliant. I do not know how flowers work... When gender dies, I must find a way to remain fabulous. One thing about psychosis is that the physics are fabulous.’ So is this astonishing first book. Welcome to Between the Covers, Rob Macaisa Colgate.”

Rob Macaisa Colgate: Hi. [laughter] I suppose that's all true. [laughter] I'm so in the poems all the time, and the outside stuff is very helpful to support the poems. Sometimes you hear that back, and it's like, “I guess. I guess.” But it's good to remember that behind anything that would be in a bio are the poems themselves. I think that's where my head is a lot. But a generous introduction. You're in my office feeling strange. [laughter]

DN: Well, you were a speaker last year in the School of Disability Studies at TMU as part of an event called (Not) Writing Access: Crip Mad Poetics. At that time, you shared a journey you went through around your own self-conception, looking at what your impulse originally was to study neuroscience, your first encounter with poetry, and what impulse and framing and desire your early poems were arising from too. I think this might be a good place to start, as I think many of these questions run through both of your books, but in different ways. It also will ground some of what you explore in the poetry around medicine—both taking medicine, but also medicine in the field—which we’ll talk about later. But let’s talk about your relationship to yourself in relation to your desire to pursue an undergraduate degree in neuroscience, then the poetry prior to your encounter with crip theory and disability poetics.

RMC: Yeah, I think that’s a beautiful place to start. You know, I was a little late to this recording because I was trying to get tickets to Lorde. You know, the musical artist Lorde?

DN: Oh, really?

RMC: Yeah, I was like, “Oh, I'm having a busy morning.” I was just in the Ticketmaster queue.

DN: Weirdly, her mom listens to this show.

RMC: Does she really? Sonja?

DN: So you can just say hi. [laughs]

RMC: Sonia, I can’t believe you’re listening to this. If you are, can you get me into the Chicago show? Because it is sold out. I mean, I got in the queue. I didn’t stand a chance. But Lorde and I are the same age. She started as a 16-year-old and I was 16. I just remember being 16, probably more vividly than I remember this past year. I don’t think I’m ever not that 16-year-old. I think that's where a lot of my self-conception started. It's also when I had my first manic episode, which I think activated a lot of how I understand myself. So when I am writing poetry, even as it's developed and become a little more researched, a little more studied—I get the MFA, I focus on disability studies, I do more scholarly work—when I sit down to write the poem, whether it was writing Hardly Creatures or writing things in my MFA or sneaking poems in late at night in undergrad, I'm never not a teenager on Tumblr in a suburb trying to sort out messy feelings, which I think is a really natural way to come to it as a teenager. Then with my adult life, feeling some impetus to do something with my life, but also knowing that I genuinely wouldn't be able to care about anything but messy feelings, so finding maybe more adult, maybe more acceptable ways to do that. I think that's what brought me to neuroscience. In my head, I was like, "Oh, there's probably just a one-to-one relationship between physical chemical processes happening in the brain and the results of these feelings." I was going into college being like, "Well, I'll just crack the code and then I won't be like this anymore. It'll all be good. I'll just sort of figure out the right neurotransmitters. I'm going to learn something about synapses that is going to completely fix me." It was a very curative way I went into things. I also really felt like I should stay in STEM. I was interested in everything as a high schooler, but I was like, "Well, if I'm interested in everything, probably do the more stable, acceptable thing in college." So that's really what brought me to neuroscience. I think the neuroscience is still in there when I'm writing. It does feel helpful to ground in the physical body. I also think when I was studying neuroscience, it wasn't quite messy enough for me. I think that's maybe why I had to pivot back to poetry with my whole chest. I think trying to technicalize what felt messy, like I've been saying, but also not just messy, but more real and more earnest and more unavoidable, I think I thought it would feel a lot better to reduce it to something quantitative. I don't think that satisfaction was there. I think that's why I started to drift away from neuroscience. Then I was just floating for a while before I found disability studies. But after I was like, "I don't know if being a neuroscientist is going to be my way to keep feeling at the center of my life." I remember I was taking a seminar with Claudia in undergrad. She gave us this very simple definition of poetry—it doesn't say this is what Claudia actually said—but I remember it as: what separated poetry from prose or other genres was its inherent emotionality, its inherent dealing with feeling. I think hearing that at the very end of undergrad maybe gave me some permission to pivot over to poems. But it wasn't really until I started doing disability studies that I think I found a way to both lock in that technical side of my mind with an opportunity to still be artistic and imprecise and scattered in the way that I think poetry provides. But what felt good throughout all of this—no matter what I was studying, no matter what I wasn't studying, who I was having as professors or not—was the sun would go down, it would hit 1:00 AM, I would be gutted beyond belief over nothing I could explain. I would just write in my notebook in my bed. That never changed and that never has changed and I don't want it to change because that is actually what keeps me in poetry, is a chance to grapple with myself even if what I'm writing about isn't about myself. Hardly Creatures is a very community-oriented book. Of course there's a speaker at the center, but when you're writing the poem, it's inherently personal. It's inherently an inner excavation. Getting to do that—the utter privilege of getting to do that—means so much to me that I think I'm willing to do scholarly research, I'm willing to spend time applying to ridiculous fellowships, I'm willing to go on a press tour for this book. Those all are satellites. But what really is the Earth that they're all rotating around is the fact that every time I return to the poem, I am as Rob as possible.

DN: In that same talk, you describe a watershed moment for you taking a course with Alison Kafer, the director of the LGBTQ Studies Department at University of Texas, Austin. You described it as things shifting from a medical and individualistic model to a social model, which shifts in your poetry as well, or your conception around poetry as well. Could you talk to us a little bit about what that means for you or what that encounter in that class meant for you? Because it feels like, as you just alluded to with Hardly Creatures being a community project, that perhaps this is the first moment when you began to conceive of the possibility of it being something other than a purely, let's say, individual and confessional project.

RMC: Yeah. I almost wasn't in that class. I was signed up to take another class. We were short a poetry seminar that semester, so I had to go into the English department. I was going to take a life writing class. I went to the first meeting and I said, "What is this? I don't know about a life. I don't know anything about a life." I didn't have a life at that point. [laughter] I was 22. So I was scrambling to find something else. There was a crip theory seminar at the exact same time. I said, "You know what? That sounds like something I might be interested in." I had spent all this time studying neuroscience. I had decided I was going to pursue poetry. I wanted to get this MFA. At no point had it ever crossed my mind that anything I was concerned with could be disability, which I think speaks in part to just still our society's conception of disability. It is one of those things that probably almost everyone could identify with, also that probably almost everyone would never think to identify with until they were really confronted with it. I ended up taking that course and it did feel like a tidal wave or something. It did feel like there was this huge wash and there was this sudden silence that let me hear what had maybe been there beyond the waves for a while. I think something that troubled me with the medical model of disability—which, as a primer, is just understanding disabilities as medical pathologies that need treatments and/or cure, cure meaning the elimination of a pathology—I think it's hard being in psychiatry because it is medicine and so it is cure-centric, right? I mean, psychiatrists will often tell you, "This is something you live with forever. There is no cure. There's just management," but there is a notion of cure behind the management. You're simultaneously being told that something is very wrong with you and it's really bad and it needs to be addressed and we're going to do everything we can to make this as close to non-existent as possible. But then when you're being told that you live with it forever and there is no cure, and they're also like, "It's okay to feel this way. This is just a part of you that's going to be a part of you forever," it's a very troublesome dialectic. And I love dialectics, but this one really challenged me because I felt like psychiatry was saying at the same time, "This is part of you. You'll never get rid of it. And it's really bad, we have to minimize it as much as possible." So to be told by a doctor that, "Here's a brand new part of you. It's awful," that doesn't feel good, like ever. I just think about translating that to any other way of existing. I think a lot about disability in the lens of queerness. That idea of just that—just homophobia, right? The notion of, "Oh, you're gay, and that's bad," right? That sounds ridiculous nowadays because we've made some progress with queer rights. No one's going to tell you, "You're gay, that's bad." But doctors will tell you, "You're disabled, that's bad." You don't think that that wouldn't be right, because they're doctors, and they're helping you. Maybe the more challenging thing in this framework of queerness and disability is like, queerness, okay, fun, love to be gay. Disability, often very challenging, right? You want to believe that this part of you is bad because it does hurt and it is challenging. So just looking at something like my schizoaffective disorder through medicine, it's just a tough way to live because you are denying a part of yourself that you are also trying to accept at the same point. You really have to choose one. So this question is the first time I encountered the social model of disability, which instead of medical pathologies that require cure, we're just thinking of value-neutral characteristics that require access, that require accommodation, that require some space for them. I think that class was the first time that I thought that having schizoaffective disorder wasn't something wrong with me. That was so delicious, to not be inherently wrong. I was obsessed with that. I loved just the idea that I could be the way I was and it wasn't bad, which feels so baseline. We're telling kids growing up, "Just be yourself," right? But psychiatry is like, "Well, don't do that. Certainly don't be yourself if that's who you are." So in a very reductive way, I was like, "Oh my gosh, I could just be myself." Of course, there was much more scholarly theory that I learned in that class. Of course, it then set me off on this disability studies journey. But the heart of it really was, it was the first time I ever considered that something might not be wrong with me. I was grateful for that. I was also fascinated by that. I remember, too, my first year or two of disability studies, it was really hard because I really did feel like something was wrong with me. It felt hard to deny that, too, when there was so much challenge and strife with the schizoaffective disorder. When I would come out of a psychotic episode, I was like, "Okay, that certainly felt bad. Surely this is something wrong." I just spent a lot of that year trying to grab onto the very basic concepts of disability as a social construct. That was also peak pandemic. It was a spring 2020 semester class when I took that crip theory class. So I have tons of memories of staring up at my popcorn ceilings in Austin for hours—no phone, no music, no books—just actively thinking, being like, "How does this make sense?" Running through scenarios and running through memories and running through new theories and then getting fed up and just deciding I wouldn't think about it and leaving myself an out. "You can always leave disability studies if you decide this is a sham and there's something wrong with you." I feel really grateful to have had that time. I already had the free time of the MFA. We had a lot less going on during the quarantine phase of the pandemic. So I just thought about it, and I still think about it all the time because it is still hard on the day to day. But then what I spent a lot of the rest of the MFA doing was writing a very me-centric book. Figuring out, "How does this make sense, this new revelation I've had that nothing's wrong with me? How am I going to grapple with that when this thing hurts me and when this thing pushes people away?" I feel grateful that I was able to spend those years really grappling with the self. Because then when I moved to Toronto and when I started conceptualizing Hardly Creatures, I felt like I had done the work I needed to understand myself as disabled in a social way that I could start extending outside of myself and seeing what disability community looked like and seeing what other folks' experience of disability was like compared to mine. But it's a very, very internal process, which is how I function. I'm very introverted. I don't like being around people. Poetry I only came to because it was an art form you could do totally alone. So a lot of time on the inside, I think, went into the poems that were the poems before Hardly Creatures. You know, Hardly Creatures is a debut. It also has a mountain of things happening before it.

DN: Well, Hardly Creatures opens with an epigraph by the DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark that goes, "Too often all we have, a dead end, leading nowhere: captions without images, lyrics without music, raised lines without color, labels without objects, descriptions without anchors." John Lee Clark came up on the show when Raymond Antrobus was a guest, and I talked about an interview Clark gave where he shared that he isn't able to read nearly any contemporary poetry because no one seems to care about braille readers in poetry. His main source of reading material is Project Gutenberg, which means he could only read the poets who've been dead for the required 90 years to be included there. So he's often startled when someone says to him that his poetry reminds them of Frank O'Hara or Robert Lowell, because he's never read them. It's more out-of-fashion poets like G.K. Chesterton and Christina Rossetti that he would think of as his influences. I bring this up because to me it feels like your two books take the situation that Clark raises in the epigraph and go opposite ways with it. Our main protagonist, Danilo, in My Love is Water, feels wrong, that his hands are too big, that his love is too big. His lover Jason doesn't love him, and even if he did, not only does Jason wish he were different, but the world itself in this play is a lot like our world in the sense that it doesn't accommodate Danilo and the ways Danilo is different. And Danilo wants those ways that he's different to go away. But Hardly Creatures imagines a world for our protagonist that is the opposite of John Lee Clark's epigraph, where needs and desires are anticipated, and where our narrator's lover, Eli, anticipates them with great care. I wondered if this felt like a good characterization of these two projects side by side. Either way, if you could put them side by side for a minute and compare and contrast them in relationship to care.

RMC: One of the things that maybe makes their duality seem a little confusing is I know My Love is Water is coming out second, but it was written first. It was written far before Hardly Creatures. It was written in 2021 and 2022 when I was living in Austin. It's part of that personal excavation I was talking about earlier. It was part of the grappling with the self. In both these books, the speaker is very much based on me, but I would never identify the speaker as myself because there are a lot of liberties taken; those little poetic lies that tell the truth. I think when I was writing My Love is Water, I was looking for a way to talk about what I needed to talk about that also didn't bore me. I was getting a little sick of myself. I was reaching a point where I felt like I just kept writing the poem I knew how to write about the things I knew how to talk about. I didn't want that. Because I really believe in poems as their own living creatures. I felt like the poems were not happy with the lives I was giving them. They were content with them, maybe. But I thought I could give them more meaningful lives. So when I went into writing My Love is Water, I wanted to find a way to heighten the drama of the situations that Danilo finds himself in based on the situations I found myself in, in a way that made them appear how they felt. I don't know anything about theater. I don't watch many plays. I've never taken a playwriting class. I don't particularly like plays, which is an awful thing to say as a new playwright. [laughter] But I think really I was drawn to the play script form because I needed to see my own experiences heightened into some melodramatic level to not feel like I was being absolutely ridiculous about them. I'm pretty good at pulling out of myself and looking at me and taking a detached look and being like, "Are you being low-key bonkers?" I often am. So I just couldn't stand myself. [laughter] I couldn't stand how dramatic I felt. I said, "Okay, let's get a little bit dramatic." I was also reading a bunch of Anne Carson. She was my first big turn to poetry back in high school when I read Autobiography of Red. I was reading a lot of Anne Carson and An Oresteia. I was like, "Okay, well, this seems dramatic," quite literally and figuratively. It was also, we were coming out of full quarantine, we were getting our first vaccines, and we were starting to have parties again. I was like, "Oh my gosh, this is one of the most beautiful things I've ever encountered." I remember the first party I ever threw in my life was a post-vaccine party because my roommates were out of town. I had a big living room. I invited all my friends over and we drank a bunch and we were like, it’s like 3:00 AM and I'm looking around and people are half crying in each other's arms because they're just spilling all their secrets and their feelings and things we haven't been able to talk about together in a year. I was so moved by the party that I was like, "Okay, this play has to be at a party. This is such a dramatic place. It's going to be a play to even heighten that drama." But I think that's what brought a play form. Then I was like, this way, if things seem dramatic and ridiculous, at least they are supposed to be that way, as opposed to when I'm feeling them, and I feel like they should not be that dramatic and ridiculous. That's what brought me into the play. When I finished the play, it was cathartic, it was purgative. I felt like I got somewhere, start to finish. You know, the play was actually how I even ended up coming into my own gender as Bakla. I didn't know about the gender constructs that exist in the Philippines. I grew up in the States. I've lived here my whole life, except for when I was in Canada. I've never been to the Philippines. I don't speak Tagalog. So I didn't know much about traditional Filipino gender, especially because a lot of that information was lost to colonization and it's only started to creep back in the more modern era. But I was just looking up stuff about Filipino gender when I was writing Danilo. But I remember sitting in my apartment in Austin, reading the Wikipedia page for Bakla and being like, "Oh." And I never questioned my gender. I just felt like a Filipino gay guy. But I did very much understand that my experience of queerness was different from the white gays around me. I joked that being gay made me able to come out as Asian. [laughter] I didn't really think too much about being Filipino. When I was growing up, I went to Catholic school, my life was very white. Then I started dating in college. I was like, "Oh, okay, I'm having a very different experience from the white people around me." So to start to understand gender as something that could be inherently tied to race, to know that there was not just language and framework for that in the Philippines, but deep cultural history, it was incredible. I hadn't questioned my gender. Then I suddenly was like, "Oh, got it. Bakla. Cool." It was like I didn't have gender dysphoria, but then I moved immediately into gender euphoria. I'm a very, very lucky queer person. [laughter] But yeah, the play really got me somewhere. Then when I was finished with it, I almost forgot about it. Again, I don't love playwriting. I don't love theater. So I was reading it back. Exactly what my intention was when I set out to write it was giving me the ick when I read it back. I was like, "This is so dramatic. Would you calm down a little bit?" Which I guess means I did what I set out to, but I was just reading and I said, "Oh my gosh, this guy, this little Bakla in this play, he is too much." I was over it, which was the point. Yeah. So I set it aside and I kind of forgot about it. So I finished it, then pretty soon after moved to Toronto and started working on the thinking and the drafting that would eventually become Hardly Creatures. So when I got to Hardly Creatures, not only had I done the processing that the play gave me, I had also very much decided to back burner it. I said, I figured myself out a lot on many different levels. That was so good and helpful. This could stay in the archives. You know, I have all sorts of complex feelings about publishing and being forward-facing. But I felt the play had done internally for me what I had needed it to do. It had done more than I thought it could do for me. So I set it aside. Sometimes I compartmentalize a bit. Sometimes I'm a little too spreadsheets. I'm a little too Virgo Moon. I'm all of that.

DN: I'm Virgo Moon.

RMC: Are you Virgo Moon?

DN: I'm Virgo Moon.

RMC: What's your sun?

DN: Taurus.

RMC: I'm a Taurus Sun.

DN: No way.

RMC: What's your rising?

DN: Scorpio.

RMC: Mine's Cancer. Whoa.

DN: Okay.

RMC: When's your birthday? Did it just happen?

DN: It's in April, yeah.

RMC: Okay. Mine's on Friday.

DN: Okay. Happy birthday.

RMC: Thank you. So you know the Virgo Moon dad.

DN: I know the Virgo Moon, whether I want to or not. [laughter]

RMC: Yes. Everything is just—I love to schedule my GCal down to the 15 minutes, even when that's not how emotions work. I think I said, I did the play. I did the emotions. Good. Done. Square away. Do the community thing now. You did what you needed to for yourself. Move forward. I think it worked, but I wouldn't suggest that to anyone, to say, "I worked through it. Done. Bye." But that is, I think, what I did. That is what led me from the play to Hardly Creatures.

DN: Well, let's spend some time with what the community orientation looks like. Hardly Creatures is an incredibly spatial book with rooms, even bathrooms, and benches, and more. But before we step into it, I want to mention the frame and the space within which we are talking, you and I, and hear your thoughts about it first. Because Graywolf and Tin House hosted a joint online gathering of their respective editors to present their authors from their spring lists. When you spoke, you talked about the importance of digital spaces and keeping digital spaces alive. My show, before the pandemic, was in-person only, and I had always felt like there was something intangible yet important that was generated by two bodies being in the same room, an intimacy that couldn't be recreated through the screen at a distance. But since the show moved to remote only four years ago, I've completely changed my mind on this. In fact, that intangible thing in the room together may or may not be a good thing, depending on the circumstances. Guests who get to talk to me not in an unfamiliar environment, but in their home—not on book tour, but in their preferred room and chair, maybe with their cat in the windowsill or their favorite cup of tea, surrounded by their books, having chosen the time of day and the day that they prefer—I think more often than not, that promotes intimacy and connection at a distance somehow. I also think of how at the Graywolf and Tin House event, you were sitting on your bed, which you described to us as your soft office, which instantly charmed everybody in that conversation. But speak to us a moment about the digital and the virtual, because I believe, you didn't really go into it in depth, but I believe you're thinking of it in terms of questions of access, which is not really what I was thinking about. But it is also a question of intimacy.

RMC: Absolutely. That's such a great question. I'm glad you saw that event. It was diabolical. They put me after or before, they put me right adjacent to Harryette Mullen.

DN: I know.

RMC: The only other poet in that call. [laughter] I couldn't believe the way they played in my face like that. I was just so—I had been reading my copy of Recyclopedia early that week. Anyway, yeah, the virtual and the digital versus the physical. I never want to clock the T of the physical space because that intangible, it's absolutely there. Post-quarantine, post-vaccine, when we started to gather in person more, it was incredible to have that in-person connection. I think where my challenge lies is people really viewing digital as a substitute for the in-person, the physical, as opposed to just its own thing. It was a substitute at the beginning of the pandemic for a lot of us, especially if you were in the middle of a semester or had been going into the office. It was a literal substitute. But we're mid-pandemic, we're late-pandemic right now. Shifting the mode of thought around gathering, around digital gathering, as not a substitute, not even an alternative, just its own thing, is really important for access. There are disabled folks whose only spaces are digital spaces, for any sort of reason. There's chronic fatigue syndrome, there's immunocompromise. I don't leave the house a lot just because I'm sleepy. I take these antipsychotics that make me so sleepy. To be able to access a community at will—I think there's a line somewhere in Hope Scrolling at the beginning—"The addiction not to my phone but to the people inside my phone." To be able to open community at will, to close it at will—I think about that a lot with digital spaces. And I'm always trying to make a case for them, especially because there are digital spaces that people seem fine with. People love to text. People have Reddit. People are on the Twitter or whatever. But then when the event is on Zoom, people are all upset about it. But I also think maybe something that folks react to is the early part of the pandemic was very hard on most people. It's a reawakening of the negative energy they felt during early quarantine when they have to be back on Zoom, right? It takes them to that negative place. I totally understand that. It makes a lot of sense. But we can grow. We can think about things in different ways. The digital just feels so sacred to me because there are some people I only know digitally, right? There are times when I want to be connected to people, but I can't get out of bed. Digital platforms to me are just absolutely rife with possibility in the way the physical can't be, because the physical is quite constrained. The physical can also be very inaccessible, right? I have a good friend who uses a power chair. There are certain places we can't go because there's one concrete step going up into the building. So we have to meet somewhere else. So the digital is just limitless. This isn't to say every digital space is perfect, or even when it's not an alternative or a substitute for the physical, that it is an ecstatic one. I am just so pissed off every day. Not pissed off. I'm not an angry person. I don't get angry. I get sad. But I am devastated day to day watching wisdom and thought crumble at the hands of AI. That really troubles me. That is in the digital space. It's hard. You can't make any blanket statements about the digital space. But I think it's going to be really important moving forward to maintain nuance if we're going to understand what access actually means.

DN: Well, before we hear some poems, we have a question for you about poetry and the digital from the poet Gabrielle Grace Hogan. Gabby is the author of the chapbooks Soft Obliteration and Love Me With the Fierce Horse of Your Heart, which is winner in my mind of best book title ever. She is assistant poetry editor at Foglifter. So here's a question for you from Gabby.

Gabrielle Grace Hogan: Hi, Diva. It's Gabby. My question for you is, what do you believe is the significance of including such specific contemporary references in your work, such as Wendy Williams, Anetra, Lana Del Rey, the entirety of the poem Hope Scrolling, etc., especially considering many of these references are rooted in queer digital spaces? Love you.

RMC: That's my best friend. I love her so much. We were a cohort of two at our MFA. There was supposed to be three poets. One of the poets dropped out. Thank God we became best friends. It could have gone really wrong. I love Gabby so much. Thank you for that question, Gabby. The importance of the contemporary, the digital, I don't think I'm ever going to be able to write poems that are not me. I think going back to that 16-year-old in the dark on Tumblr, even as things become more researched, become more scholarly, I'm working on big, very concerted projects with ideas and themes, when I'm in that notebook with my mechanical pencil, I can't erase myself from it. I also just want to do what I want. I want to do whatever I want. It's my poem. It's a collaboration between me and the living being of the poem. But the poem's on my side. I'm helping it be alive. The poem understands when I bring pieces of myself into it. It works with me to make sure that it can still have its own body and its own breath. But I also think in terms of the contemporary, I'm not super concerned with the work being timeless literature. Hardly Creatures doesn't have to necessarily feel like it could have come out of any particular era because that's not the project that it is. There's always going to be another book. There's always going to be more poems. If I want a book of lyrical poems that feels like it could have floated out of the New York School, I can go and write that if I want to. But I came in with real intentions for this book, and I knew that if it was going to do what I wanted it to do, it would have to stay focused. I am a big—not fan of—but I am very liable to excess. I am very liable to trying to put everything all in one space. I'm constantly coaching myself back: "There'll be another poem. There'll be another project. There'll be another stanza. It doesn't have to happen here." I wanted Hardly Creatures to be expansive. I didn't just want it to be scholarly about disability studies. I wanted it to be very personal. But I also knew there were certain lines that were going to have to be drawn if it was going to fit the mold of a poetry collection. So I went in with intention and I wanted it to be a book of the times, because disability isn't theoretical. It's something that everyone lives with at some point or another in their lives. It's something that is happening right now in the world. I'm being disabled right now. All my friends are being disabled right now. So the ways that we think about living with it and celebrating it and managing it, if they're going to be concrete, they need to be temporally bound. So it didn't make any sense to me to write this book in a vacuum about disability, because if I wanted to do that, I would write scholarly theory. But I want to be a poet. I want to write poems. So if I was going to contend with the current state of disability, if this book was going to go out in the world and take care of people and do that caretaking in such a way that people feel transformed to take care of their own disabilities, then it had to be relevant. So part of it is me. I want to say what I want. I'm a very pop culture diva. But it was also like, I'm not writing theory. This is praxis. This book is something that people are going to pick up and be able to think about their own lives in the current moment. That's what this book is. A lot of it was just me too thinking, "What's fun?" I have to enjoy the poems. The poems can get heavy. This is my most lighthearted book, I think. My Love Is Water is not very lighthearted. The new stuff I'm working on is sad. But here I was like, "All right, I want to have some fun with this. I want to make sure Wendy Williams gets her shoutout. Native New Yorker on The Masked Singer. I live for that." [laughter] So I wasn't going to not enjoy writing the book. Even if I was writing the book as a project, even if I wanted the book to take care of people, even if the book was part of trying to establish a career that allows me to keep poetry at the center of my life, I'm not going to sit down and have a bad time writing the poems. I'm not going to block Wendy Williams out of my head for the sake of crip theory.

DN: Yeah. Well, before we talk about Hardly Creatures more fully, let's hear a couple poems. I was hoping we could hear the poem in the entryway to the book, We Do Not Enter the Gallery, then the first poem in the section called Access Guide, a poem called Information.

RMC: Of course. Originally, I wanted We Do Not Enter the Gallery to happen before anything. It was going to happen before the table of contents, before the land acknowledgement—no, after the land acknowledgement, before the table of contents—because I wanted it to be a literal vestibule walking in to the gallery. You don't even buy your tickets till you're through the first door or whatever. But we had to shift it just for access reasons for e-books, which I was happy to do. But readers, if you're listening to this, you can read We Do Not Enter the Gallery, then go back into things. I'm a big proponent of poem first. When I'm doing a reading, the first thing I say when I get up there is a poem. Then I do my intro, my visual description, all of that. But I trust poems so much more than anything I have to say. So I would rather start with them, which is hilarious, because I just prefaced this poem instead of reading it. [laughter] But we've been talking for a while, so we're already into the thick of it.

DN: We are.

RMC: Okay, this is We Do Not Enter the Gallery.

[Rob Macaisa Colgate reads the poems called "We Do Not Enter the Gallery" and "Information" from Hardly Creatures]

DN: We've been listening to Rob Macaisa Colgate read from Hardly Creatures. I agree with Claudia Rankine and Chen Chen that this book is like no other I've ever experienced. This is true in multiple ways, I think. But the one that is most immediately apparent is the form of the book as a whole, where we move from room to room, where there are places to pause—benches or even sensory rooms that invite us to return to them—saying, "Feel free to flip back here whenever you need. Stay as long as you want." There's accessible transit information, a gift shop. There's even a page called I Need a Minute that simply says, "Slow down, there is no poem on this page." On another, an empty frame for the artist who is too sick to even finish the work or make it to the gallery. I have several questions about this, but the first is related to something you say in the author's note in the advance reader's copy, "In Toronto, I bore witness to acts of access more stunningly creative than even the art that surrounded us. I was awed at how visual art could be not only about disability, but accessible in experience. We deserve more than poems merely about disability. We deserve poems that meet our needs, needs that we may not have realized we even have." Then also, before the first poem, there's a page called Access Legend, which is a full page of symbols indicating everything from translation available to trigger warning, to please touch, to physically accessible, to low vision guided tour. Every poem in the book then has one or more of these symbols accompanying it, usually at the top, but also sometimes alongside the poem in various places. We also, at the beginning of each section, get what is called an access check-in that suggests, based on various criteria, different pages that one might consider turning to. This all makes me think of a term of Mia Mingus's you've brought up in talks, that of access intimacy. But I was hoping maybe you could talk for a moment about the access legend, the access check-ins, or what is meant by access intimacy, and perhaps in relationship to the experiences you mentioned in the author's note about what you bore witness to in Toronto, and if perhaps anything that you witnessed there is part of informing these choices that you're making around the legend or the check-in and all the other ways in which we're walking in a very oriented way through this new space together.

RMC: Absolutely. Anyone who listened to any interview with me during this book moment will hear me talk about Tangled Art + Disability, Disability Arts Gallery in Toronto, where I was poet-in-residence. You know, it's run by disabled folks. We put on shows by disabled folks. There's often disabled content in the work. But I definitely came into my life in Toronto a little fed up with disability poetics. There's one main disability poetry anthology right now. I read it my last semester of my MFA during an independent study with Alison Kafer. We got onto our Zoom meeting and we were like, "This was bad." Nothing against the individual poems themselves—they were all well-written, well-composed—but there was very little formal variety. There was very little touching on mental disability. It's an old book. It's a very white book. The hardest part for me was that it was just poems about disability. Something that's so important to me about poetry is that it's formal. There is so much to the poem besides the language itself and the content. I think if I wanted to be very straightforward about content, I would write prose. But I don't. I want to engage all the things that make poetry a genre with arms sticking out in all sorts of places. At the same time, I didn't know what any of that meant in my head. I was like, "Okay, I'm not satisfied with poems about disability. I want more. I don't know what more is." So really, my first year in Toronto, I wrote very little. I was just absorbing. I was learning. I was thinking and spending a lot of time at Tangled, and I was helping when we were putting up new shows, I was helping run events around them. It was the first time I was really encountering some of the creative access symbols that make their way into the legend. It was the first time, I think the biggest one for me was seeing please touch symbols, which just felt so antithetical to the idea of an art gallery that I had in my head at the time. I've always wanted to touch the art. One of my really good friends from college, her name is Maddie, we would go to the Art Institute of Chicago. We went once, or no, we were at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. We decided that art was really good if it made you want to lick it. [laughter] Like, if you were in the museum and you're like, "That is incredible. I want to go up and lick that with my tongue." You can't do that at most art museums. They really don't want you doing that. But to be invited to touch something in an art gallery, I was just so blown away. We had this exhibit Avere Cura and there were these plaster models of disabled ephemera. There were blister packs of pills and there were pill bottles and there were gauze. You were allowed to just pick them up and handle them. The fact that I was like, "Oh, okay, the art is making sculptures out of disabled ephemera. Cool ideas." But then the experience that it could be tactile for folks who are blind or low vision, for folks who prefer the sensory channel of touch, I was like, "Whoa, okay, layers to it. Love that." I think that's when I was like, "Something like that has to happen in the poems for me to feel satisfied." I think I was reaching another point during this first year too, where I was trying to draft maybe new stuff for Hardly Creatures. I had reached another point, like I described earlier happening a few years back, where I was like, "I'm still writing the poem I know how to write. It was a breakthrough to get into this new poem. That breakthrough was a while ago now. I am going to have to learn to write a different poem if I want this project I've been visioning to do what I hope it can do." So from that please touch symbol, I really just started becoming fascinated with all the different ways visual art can be accessible. We talk a lot about access being an ethos, not a checklist. It's not just making sure there's interpretation at the event. It's being open to the possibilities of what people might need. But checklists can be helpful to stick to an ethos. Tangled has this access toolkit. It's a free PDF on their website. They put it together with some scholars and with some artists. It's a very nuts-and-bolts overview of how to make an art space accessible. I printed that out and I brought it to the residency where I finished most of the book. It was supremely helpful. They were helpful because they were starting to expand the way I was looking at what a poem could do. They brought my attention to the physical experience of reading a poem. Another way I started thinking about all the access features in this book is I was trying to read a lot and I was trying to pay attention to what it felt like when I was reading. I was trying to read collections. I also read for a couple literary magazines, and I would notice when I got to a new poem and something about it helped me focus in, I would really notice when I would get to the next poem and be like, "Oh my gosh, I just read a very dense highland and now there's another one. How am I going to have the energy for that?" I would notice when I needed to take a break partway through a collection and come back to finish it later. I would notice too when shifts in form and content were able to keep me in the book or were able to excuse me out of it. So it was a lot of observing myself from above, like a little ghost while I was reading and trying to be very in touch with, "What does it feel like to read a poem? What can I do to meet my needs?" Because I think my least favorite thing is when I'm trying to read submissions to a literary magazine with a generous heart that loves poetry. Instead I'm coming into it worn out and tired and unfocused. I get scared of missing something good that I would have been able to understand its goodness in a different headspace. I want to give every poem its time and my energy. So that informed a lot of how I was thinking about accessibility in this book. That also then helped me decide which symbols are going to be in the legend. Most of the symbols are actual universal access symbols. Then some of them, like Please Touch, isn't totally universal yet. We use it at Tangled. People use it in other spaces. But there are some others, like Assistive Tablet. That symbol isn't everywhere, but there are assistive tablets at some galleries, at art spaces, at museums, at other just public spaces. So I wrote all the poems. I still will get a little rigorous and literary and very in the language of the poem when I'm writing it. Then I figured out what access symbols each poem needed after I wrote it. The most exciting part was I originally thought I was maybe going to use like five access symbols. There was going to be one per poem and it was going to be very literal. But I had a lot of time to play at the residency I was at. I think the first time I created a visual poem with the access symbols, I want to say, is in Therapist, where I turned the figures around so that the helpee was helping who was supposed to be the helper. I was like, "Oh, whoa." It surprised me in the way that writing a poem surprises you, but it was this little visual poem. Then I had that sinking feeling where I was like, "I'm going to have to try to hold the symbols to that standard for every poem," which was such a big task that I didn't envision when I was writing the book. But I knew the poems needed it. So then after I was starting to put together visual symbol poetry in the corners of all the poems, I had always envisioned an access support worker, an access doula, checking in with the reader throughout the book, breaking that fourth wall. I was originally going to have like in the bottom corner, something very small and italicized, just like a little peek. Desiree Bailey's What Noise Against the Cane has this essay happening at the bottom along through like the whole book. I was like, "That's cool. That's cool." But then what happened is it was like, there was a poem and there were access symbols. Then there was stuff at the bottom. I was like, "Cluttered. Not more accessible. Spreading the mind around. Not what I wanted." I said, "Okay, well, let's pull back. That access doula doesn’t have to be there all the time." So I said, "What if they just checked in before each wing?" Just like occasional check-ins. It also felt less overbearing. You know when someone’s checking in a little too much and it’s like, "I’m fine. I’m okay." And I appreciate it, but sometimes you don’t. And so I said, "Oh, okay, we'll just have them say something at the beginning of each wing." And so then I was like, "All right, now I gotta write these little poems for each wing." So I was looking in the wing for inspiration, and then that's when the inspiration for these centos came about. And I'm such a formalist. I love form. And so a chance to engage another traditional poetic form in such a way that also made sense for the book, I remember feeling very happy when I realized I got to write centos for each wing to introduce each wing. And then it also felt like, oh, this is a good way to quite literally preview the wing and say, "Hey, there's going to be some stuff in here, just letting you know, we're checking in." That’s been my favorite thing about poetry is when the form locks into the content, just when they understand each other and when they elevate each other and when it just feels right, I chase that high constantly in my day-to-day life, even when I'm not writing poems. So for the way that a cento is composed with lines from different poems to also then act as a preview about those poems, but for that to mirror the preview cautioning before maybe entering a room that might be challenging, that felt really good. It took away a lot of the clutter on the page. So that’s what got me into those access check-ins.

DN: Well, let’s head together to the gender-neutral bathroom and hear the poem, Ode to Pissing.

RMC: Okay. This is Ode to Pissing.

[Rob Macaisa Colgate reads the poem called "Ode to Pissing" from Hardly Creatures]

DN: We’ve been listening to Rob Macaisa Colgate read from Hardly Creatures. Another element that I think is as prominent and unique as the spatial element in Hardly Creatures is a tension that exists in both of your books around your relationship to yourself, unmedicated versus medicated, which I think speaks to what you’ve already discussed about finding a frame where who you are is good, is okay, but also your relationship between who you are in a larger sense compared to the "normal world." In your author’s note in the galley, you talk about how the inherent solitude of poetry made it possible to give your whole self over to the art. But you also talk about social withdrawal as a hallmark feature of schizoaffective disorder, and that when you realized placing poetry at the center of your life was going to require a public-facing component, your response was to say to yourself, "Okay, let’s really go for it and invite everyone." Both books feel like they do this, this invitation, I think. There are poems with titles like Sestina Medicated on 800 Milligrams of Antipsychotics and Abecedarian After Forgetting Yesterday’s Medication. You’ve talked within the work and also publicly about how the medications make you incredibly sleepy, that if you’re going home with someone you met at a club, you have to strategize when to take your meds. If you forget altogether, you can’t take them in the morning because of how sedating they are, but psychosis can come super quickly, and so you need to get out of there fast. The poems have lines like, "My first seven boyfriends make my psychosis worse," and then the parenthetical, "(this isn’t necessarily a bad thing because I do usually love my psychosis)," and "I skip my meds so we can all trip together." And at the party in My Love is Water in a scene called Functioning High, the partygoers break out a bag of pills and start taking the drugs with their punch. People begin to hear colors, or feel weightless, or float above the kitchen island. Another starts a conversation with the moon. Everyone but Danilo is entranced. Danilo takes his medication, his antipsychotic, and then hears nothing, no strange voices. He looks down at his body and is convinced it is his own. He has no urge to wander off. His mind has never been so present, and he cannot bring himself to dance. When the partygoers exclaim, "This party is crazy," he responds, "Yes, crazy," which is a good thing. Similarly, My Love is Water has a cover that has a sketch of a giant hand with a much smaller hand wrapped around the giant pointer finger. I didn’t realize until I read about it on your Instagram that this smaller hand is breaking the finger of the larger hand. This image is also superimposed on the background that is a psychiatric intake form. Danilo in that book feels like he’s too big. His love is too big. His hands are too big. Sometimes it feels like the psychiatric medications in these two books are like this normative-sized hand trying to force the large hand down to normal, but having to break the large hand in the process. But sometimes the medications feel like care. For instance, in the poetry collection, in a piece called Eli Invents, it’s a poem that lists the many ways every night Eli tries to lovingly trick the speaker into taking their medications as an act of care. I guess I wonder if you could talk more—you’ve talked about it some already—about this dynamic and also I think a dynamic contradiction in relation to self and identity, in relation to what is you and what isn’t you, and how you dramatize it in both of these works.

RMC: So glad you asked this question. I don’t know if I’ve ever really gotten to talk about my medication life and history, which I think is so core to my experience of disability. So here’s my prescription right now. [laughter] Okay, it’s just going to be just technical. Just pull up my Walgreens receipt. Well, so I’ve been on antipsychotics. I’ve been on the same ones now for over eight years, which feels earned. I never thought they’d get easier. Then maybe in the last year or two, they’ve gotten a touch easier. I went through so many psychiatric medications, both before and after my psychotic break. I had the worst luck with side effects. I got genetic testing done that showed that there were so many helpful meds that I just couldn’t take. We tried others. I got a life-threatening rash from one. I kept shitting myself on another one. It’s horrible. Oh, one of them I just passed out walking. It’s just all sorts of things. So when we finally got to the Seroquel—the antipsychotic I take—it was like pros and cons. It really controlled the psychosis. It didn’t really stabilize the mood, I can’t say that, but it really controlled the psychosis. And the sedative side effect was honestly a lesser evil. At the same time, it has a very short half-life. And so if I take it early one night and then the next day I’m out late at a party and it’s been over 24 hours, little bits of what I’ve learned to be features of my psychosis will start to creep in. And if I do have psychotic episodes, they’re almost always at night when it’s been the longest since I last took my meds. So I had to start taking the meds. I dropped out of college because I couldn’t do college freshly psychotic and started really taking the meds and understood, in the same way that psychiatry told me there was something to cure, that if I was going to participate—not meaningfully, but as required—in the capitalist structures of university and labor, I was going to have to be medicated, because there is no space for psychosis in the conventional world that’s been set up. At the same time, spending a lot of time in psychosis, it feels very natural. And that’s because it is. It is the natural way that my mind turns. And so I think the title of that poem, Functioning High, the high functioning, I think calling someone high functioning is maybe the conventional way to be like, "Wow, it’s schizoaffective disorder but you’re also finishing your degree and working a day job and all this stuff." But it doesn’t feel high functioning to me. I would feel high functioning if I got to be psychotic and walk around, and just live that way. A functioning high, I think of the antipsychotic medicine as a high. I’m all drugged up and I’m not myself. That’s what drugs do. They put you in an alternate reality. My alternate reality happens to be the one that matches up with most folks in conventional society. But my true reality is not the one that matches up. I also became aware that my psychosis was not inherently harmful. That is not the case for everyone’s psychosis. Inherently harmful psychoses are also valid and deserve their space. But I became aware that mine could lead me to harm, but that a lot of the harm was contextual. I was big at wandering off. I would follow voices for a long time. Then when I started hearing fewer voices, I would just follow impulse. I had to get out. I had to seek something. That would be harmful because if you fall asleep in a park and cops find you, well, that’s no good. No cops. But if I were to be in such a world that I could wander off at night, fall asleep in a field, wake up, and mosey home or to my next wander, that would be fine. I think anytime harmful urges emerged within the psychosis, they were never the fault of the psychosis. They were the fault of whatever context I was in. I think if I was convinced that my own self was something that needed to be harmed, if there had been space to fully spin out the psychosis, the self-harm wouldn’t have to happen. Or if the self-harm happens—and now here, bear with me, listeners—there is a poem in the book, A Case for Self-Harm, for a while, I was calling it bloodletting. Not physically bloodletting, but I would bloodlet my psychosis. I could feel psychotic episodes building up. I said, "I just need to go a little crazy." So I would just stay up later, wait for the meds to wear off a bit, share my location with Gabby, who asked me that wonderful question, and be like, "I’m going to wander off. Keep an eye on the location. If you don’t see me go home at some point, can you come get me?" Those were much less harmful psychotic episodes because I was able to bloodlet the madness and not bloodlet myself. So I, through just the practice of psychosis, became aware that it was my natural state and that it wasn’t an inherently harmful state. But to exist in the world, I needed to suppress it to some degree. It’s complicated because that’s how I live pretty much all the time, because so many of the things I love are in the conventional world. You know, the work I get to do—reading and writing—if I have to go to meetings, I have to be cogent. I can’t be in Schizophasia. For a long time, partners, it really wasn’t a space where I could be psychotic. Now my current partner, my life partner, there’s a lot of space for me to be psychotic around him. That feels really good, because I can be myself around the person who makes me most feel like myself. But the medicine, basically, my experience of it is maybe the opposite of what folks familiar with psychiatry might first think, where it doesn’t pull me back to normal, it pulls me back to social. One time I was at a residency and people said, "What would be your ideal artistic creating space?" Because we were talking about how nice it was to create there. I said, "No, I know this is going to sound like I’m a dog, but what I want is I need to be chipped for my location, because sometimes if my partner is trying to track me down, I turn my phone off. So I need to be chipped. Then I want a very gentle electric fence so I can wander off, but not that far. I want it on a huge expanse where I have a big field in the middle of the woods. That way I’m contained and kept an eye on, but I can wander, I can spin out, I can babble, I can do all my things without putting myself in harm’s way. Then I’m just allowed to just be there." I still dream of that. But a lot of the things I enjoy in my day-to-day life require sanity. So begrudgingly, I engage with sanity most days.

DN: I do think that your description of the dream for yourself feels connected in a way to the impulse behind Hardly Creatures, but not just for your dream, but imagining various people’s dreams being anticipated when they enter the gallery. But we have a question for you that is specific to My Love is Water, the play, from the poet and editor Felicia Zamora. Felicia is the author of eight poetry collections, including the forthcoming Murmuration Archives from Noemi Press in 2026. She’s also the poetry editor at Colorado Review. So here’s a question for you from Felicia.

Felicia Zamora: Hi, Rob. It’s Felicia. I love that David reached out to put us in conversation again. I keep thinking about our encounters and our time together at Sewanee last summer. How I knew our energies were speaking with each other then, and now our orbits get to be crossing once more. My Love is Water is a triumph. Friend, a triumph. Intellectually daring, bold in ways life-altering books must be, where specters and the cerebral dance in and out and through with each other. This book pulsates with existential thinking and philosophical urges that keep reeling in my mind. The ideas of illness, haunting, curing, mourning, temporality, and so much more live in this verse drama. A few moments that still swim inside of me—and so now basically I’m going to quote your book to you now. "When we run out of gauze to hold things together, well, we call it providence." "My favorite bodies have been the ones that leave quickly and the ones that never leave." "When the sun sets in my head, three stars take its place." "The light never dims on panic." "I need to be cured of myself." "I mourn my body growing still." "All love starts as water." Ah, friend, so good. [laughs] So much here refuses to be reduced, pushes against the damaging normativity of society, all while acknowledging the ache. My questions for you are: What is this book’s relationship to care, lack of care? Why meditate on love in scaffolds of the delicately holding on, of that which sits so close to rupture? Much of this book feels like your own philosophy, and I’m so excited to hear how you answer these questions. Thanks, Rob. Until our orbits entangle again, many hugs to you.

RMC: Thank you, Felicia. Felicia saved my life last summer. I was just at Sewanee, crashing out. I had a lot going on and felt like I couldn’t talk about it with anyone. Met her in person for the first time and she kept me afloat and has just been such a champion of mine since. I love her and her work so much. I love this question about this book as a philosophical approach to care. When I was writing this book, I was really contending with the difference between love and care. A theory I developed in my head that I think guided a lot of the book was that they are very different and that they don’t always go together. I was grappling with new relationships, disintegrations of old ones. A lot of my friends were too. You know, we were just in our twenties, fucked up over gay people. It’s like this. [laughter] But I was meditating a lot on it and thinking about how a lot of dissolved relationships—like what happens to Danilo in My Love is Water—are from imbalances of love and care. You know, you can have a relationship with a lot of love. Danilo really loves Jason. Danilo wants to take care of Jason. It seems like Jason loves Danilo but does not want to care for him. So it doesn’t work. It can happen the opposite way too, where you want to take care of someone, but you don’t love them. That doesn’t work either. Or maybe it does, but it’s useful elsewhere, right? Care attendants, I don’t necessarily think there has to be a love there. The flip side, like some friendships, you can have a lot of love for them, it’s not always your responsibility to do everything for your friends. So I think when I started thinking of them as really separate things, a lot of how I then understood relationships to work clicked into place. My understanding of a romantic partnership became based in the necessity of both love and care in both directions. There needs to be a love and there needs to be a care. On the flip side, there needs to be a willingness to accept both. So then I started looking at everything like this and being like, "Oh, there’s care there, no love," which is fine for that. [laughter] "Oh, there’s love there, no care," which is fine for that. Sometimes there’s neither. That’s okay, too. My day job, I work at a corporate chain gym, and I don’t necessarily love my corporate management. I don’t really care for them either, but I deal with it, and I really enjoy the coaching. The athletes I coach, I don't love them. [laughter] Sorry, sorry if any of my members at Orangetheory South Loop are listening, but I care for them a lot, right? I don't want them to get hurt. I want them to achieve their athletic goals. I want them to be inspired by what their bodies can do. So I think discerning the difference between love and care and then recognizing that you don't always have to have both, and learning which one is the most important in different situations, that was very useful in writing out this book. That's how I ended up looping in the Filipino nurses, thinking of the nurse as a role that requires care and does not necessarily require love. Then too, thinking about Danilo's bakla identity, him being Filipino, this long history of Filipino nurses being tasked endlessly for care, the way that they can become so draining, particularly if there is an impulse to love. I think Mari, the nurse, has a strong impulse to love. I think that's why she tries to cure. But that's maybe misplaced. Maybe that is not something she should be doing. You know, I think the nurse I maybe trust more is Lilia, who is not a nice person, not full of love, but is way more able to direct her care.

DN: Thinking of care and this book in specific, I've long been a fan of Ugly Duckling Presse. One of the first things I think of when I think of them is their care for books, not only as a nonprofit publisher of poetry, performance texts, experimental work and translation, not only because they published so many iconic books—I think of Jen Bervin's Nets, Cecilia Vicuña's Spit Temple, or Don Mee Choi’s Translation is a Mode= Translation is an Anti-Neocolonial Mode—but also because of the books as physical objects. There are handmade elements that call attention to the labor and history of bookmaking. In that spirit, when I reached out for an advanced copy of My Love is Water, they let me know that they don’t create advanced galleys, but they offered nevertheless to bind a copy for me, which meant someone took home the loose pages over the weekend and hand-sewed me a copy. I bring this all up under the auspices of care, because as many of you know, late on a recent Friday night, the National Endowment for the Arts sent out notices to many of the presses and regional theaters and other art organizations who had received grants in the last round, who had already been awarded grants and depended upon and budgeted for their confirmed existence, to tell them that the criteria for the organization had changed—not only going forward, but with great cruelty, also retroactively—and the money was being retracted. This is what Ugly Duckling Presse said on Instagram: “As the administration considers dismantling the NEA, it seems likely that federal funding for independent literature and art will end altogether. We feared and expected this. Among a plethora of other signs, seven days after Trump took office, the administration released an executive order stating that, ‘The use of federal resources to advance Marxist equity, transgenderism, and Green New Deal social engineering policies is a waste of taxpayer dollars.’” Then they continue: “Ugly Duckling Presse believes in advancing Marxist equity, transgenderism, and Green New Deal social engineering policies. We believe that taxpayer dollars are made for these purposes. We’re not sure, however, how to make up the $25,000 deficit in our next fiscal year. This deficit is equal to the wages of one part-time staff position, the production costs of one season of books, or eight months of rent and utilities. To avoid making impossible choices, we are asking you, our friends and readers, for help. Help us continue to publish literature that is American, un-American, non-commercial, beautiful, and ugly.” I bring this all up because your books are about mutual aid. In that spirit, to listeners, if you can, after you’re done listening, perhaps sending some care to Ugly Duckling Presse, I’m sure they would appreciate your support.

RMC: Yeah, support Ugly Duckling, everyone. This play would not exist without them. I wrote it and I said earlier, I put it on the back burner, and I sent it out a few times and then I just couldn’t get myself behind it mentally. So I saw Ugly Duckling was reading and I said, "Well, that’s my dream press for this project. I’m going to send it out one more time and then I’m never going to think about it again, because I don’t like it." [laughter] They ended up not only wanting to publish it, but convincing me to care about it and to look at it with love. I love this book now, but I don’t think I would have without Ugly Duckling being so generous and attentive, and caring during the process. So they’re an incredible press. The people are amazing. Please support them as much as you can.

DN: I want to ask you some questions about language and your use of language. As a first step toward doing so, I wanted to ask you about your viewing the poem as both a body and as a site of knowledge creation. I’m not sure if these are related or not. In the poem “On Sex,” you say, “Museum with no art in it. The body. Museum of unreasonable pain. The body. Museum of the body. The mind.” In an interview at the New England Review, you say, “Currently, my creative and scholarly concerns intersect the notion of the disabled poem. So often we refer to the body of a text. If a poem has a body, then that body can be disabled, and this can be a source of wonder rather than a pathology. I’m more interested in taking care of my poems and providing them with access than trying to fix or cure them. I imagine poets as support workers for our poems. The poems have all the revelations, and we just gently facilitate. Care is so reciprocal. The more I take care of poems, the more they take care of me back.” Similarly, in an event called Cross-Pollinations with Rob Colgate and Sarah Redikopp, you again talk about the poem as body and poems as extensions of the poet’s body. But here you do so in an opposite way. You are sharing an event with Redikopp, whose dissertation at York University was entitled Reparative Engagements: A Mad Feminist Approach to Politicizing Lived Experiences of Self-Harm, where she critiques the individualized and depoliticized framing of people who self-harm, when in her argument, social conditions might be such that self-harm could be a natural response to unnatural conditions. Similarly, you speak about what it means to harm the poem, thinking about where the intent comes from, the desire to harm the body, the desire to harm the poem. In your poem “I Punch Myself,” there is the line, “When I get to heaven, I will be bruised.” In the poem “A Case for Self-Harm,” there are the questions, “To be broken is to be whole or wholly alive?” Talk to us about the poem as an extension of the body, as a body itself, whether a body to care for or to bruise. Does this connection between poem and body relate to your assertion that poems are a site of knowledge creation? Or is this something else entirely, this notion of knowledge being created in the poem?