Robert Macfarlane : Is a River Alive?

Don’t miss today’s conversation with Robert Macfarlane. A polyvocal deep dive into the mysteries of words and rivers, of speech acts as spells, whorls as worlds, of grammars of animacy, of what it means to river, and to be rivered. From the Epic of Gilgamesh to Virginia Woolf’s wave in the mind to Ursula K. Le Guin’s fellow feeling to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s notion of theory as embodied and kinetic, we look at the role of the imagination, language and the body in reorienting ourselves to a world alive with us beholden to it. And we look to the water defenders and language revivers as part of together dreaming an otherwise.

The bonus audio archive contains many contributions from people mentioned today, from Alice Oswald to Natalie Diaz to Jorie Graham to Richard Powers. To learn more about how to subscribe to the supplementary material, and about all the potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers community, head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today’s conversation.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you by On Earth as It Is in Heaven, the debut short story collection by Vishwas Gaitonde, out this September from Orison Books. These globe-spanning stories feature a diverse cast of characters. A doctor and his relatives are at loggerheads over whether England will be more of a paradise if a splash of Pakistan is added. A Tamil doctor who flees his homeland torn by civil war struggles to make a new life in the American Midwest. A New Zealander visiting India strikes up an unlikely friendship with a little boy facing hard times. An American mother struggles to live without her son following the Iraq war. A Sri Lankan aboriginal finds, and then loses, her paradise when confronted with visiting researchers several years apart. These vivid characters and more demonstrate what connects us all, no matter where we're from, or where we find ourselves. Pre-order On Earth as It Is in Heaven today at orisonbooks.com. I've been anticipating today's conversation with Robert Macfarlane all year. But you could say in a certain way, I've been anticipating it, or getting ready for it, for years now. At the beginning of the conversation, I mentioned the many past conversations on the show that long-time listeners have already heard that are in conversation with Robert's work. All of these conversations, one to the next, I think got me ready to talk with Robert, where I was supported by the thinking and feeling and insight and wonder of all of these writers making work animated by similar questions in his work. Before we start, I want to mention a few of them and what they've contributed to the bonus audio archive over the years. There's Forrest Gander, who read poetry for us that he wrote in collaboration with a lichen scientist. Natalie Diaz, who read from Borges' Book of Imaginary Beings. Richard Powers, reading W. S. Merwin. Jorie Graham, reading rain poems by Edward Thomas and Robert Creeley. Alice Oswald, reading A Ballad for Anne Carson, and passages from the Book of Job, and Ross Gay, reading from Jean Valentine, just to name a few. In our talk today, we talk at one point about the utter wonder and mystery of the chrysalis and the radical transformation that happens inside it from caterpillar to butterfly or moth. Thinking of this, if you transform yourself, if you reformat yourselves from that of a listener to that of a listener-supporter by joining the Between the Covers community, the immense and vast and ever-growing bonus audio archive is only one possible thing to choose from when you do. There's the Tin House Early Readers subscription. There are rare collectibles from past guests and much more. But whatever you choose, every supporter gets the resources with each episode of what I discovered while preparing, what we referenced during the conversation, and where to go once you're done listening. For instance, with today’s conversation with Robert, someone who does so much in so many different forms and fields, I bring in a wealth of material from outside the book in the hopes of enhancing our exploration of it. Every listener-supporter is also invited to join our collective brainstorm around shaping the show going forward, who to invite in the future. You can check all of this out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today’s conversation with none other than Robert Macfarlane.

[Intro]

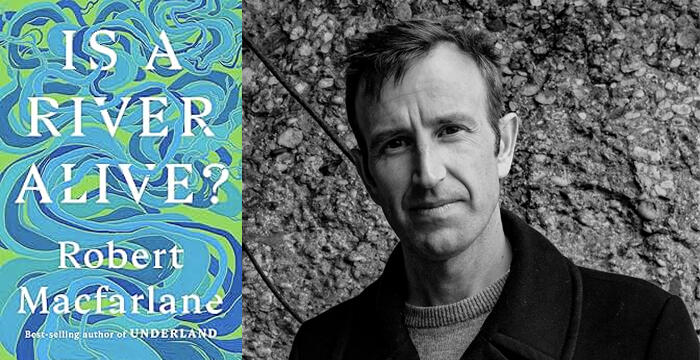

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest, the writer Robert Macfarlane, perhaps unsurprisingly, given that his grandfather was the diplomat and mountaineer Edward Peck, wrote his first book about mountains. Mountains of the Mind was an account both of the developments of Western attitudes to mountains and an exploration of why people are drawn to them, and it won the Guardian First Book Award. The Irish Times described it as a new kind of exploration writing, perhaps even the birth of a new genre, which demands a new category of its own. In the 22 years since its publication, Macfarlane has continued to develop this new genre, with bestselling and critically acclaimed books such as Wild Places, The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot, and most recently his book Underland: A Deep Time Journey, that takes us into both mythical and real subterranean spaces. It would be inadequate, however, to describe his books solely as deep engagements with the land, whether high above or deep down below. They are also deeply engaged with the mysteries of language, with books like Landmarks, which The New York Times described as part outdoor adventure story, part literary criticism, part philosophical disquisition, part linguistic excavation project, part mash note. It’s an argument for sitting down with a book. It’s also an argument for going outside and paying attention. Or his books of nature poetry and art with Jackie Morris—The Lost Words, The Lost Spells, and the upcoming The Lost Birds—books that themselves have run wild, escaping their covers to find new life in the world at large, ending up in British primary schools and hospices, used by care workers with dementia sufferers, refugees, survivors of domestic abuse and childhood cancer patients adopted for dance, outdoor theater, choral music, classical music, and a folk music festival. Macfarlane's work as a writer can also be viewed through the lens of a collaboration, with the land for sure, but also with the words we speak and write and the others who've spoken and written them before, but also with many living writers and artists, whether his book Ness, illustrated by Stanley Donwood, the films River and Mountain narrated by Willem Dafoe, or as a librettist, whether for the jazz opera Untrue Island or the recently completed libretto for a choral work called The World Tree, which will premiere with the Helsinki Chamber Choir, or as a songwriter and performer with many musicians including Johnny Flynn, with whom he collaborated on the albums Lost in the Cedar Wood and The Moon Also Rises. He has won too many awards to name. His name has even been mentioned as of late as a Nobel Prize contender, and we are lucky to have him here today to talk about his latest book, Is a River Alive? With starred reviews from Kirkus, Booklist, and Publishers Weekly, Elif Shafak says of it, “A rich and visionary work of immense beauty. Robert Macfarlane is a memory keeper. What is broken in our societies, he mends with words. Rarely does a book hold such power, passion, and poetry in its exploration of nature. Read this to feel inspired, moved, and ultimately, alive with the world.” Jorie Graham adds, “s a River Alive? is one of the best books I’ve read in a very long time―exciting, brilliantly comprehensive, mind-altering. In one of its many stunning moments, Macfarlane describes the myriad rivers trapped and buried under the concrete of our cities. ‘Daylighting’ occurs on those rare occasions when these ghost-rivers are dug out & released to the surface to feel the sun, to expand―majestic creatures―and spread life once again. To read this book is to feel your ghosted soul undergo such daylighting―metaphysical, political, emotional, linguistic. Any soul going dormant, any citizen going numb, will be revivified and propelled back to their essential core, where rage, wonder, and imagination intertwine, and a powerful hope for the earth arises. A spellbinding, life-changing work.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Robert Macfarlane.

Robert Macfarlane: Thanks, David. Wow, generous Jorie, generous Elif, what extraordinary things far, far in excess of the book itself. But thank you for that wonderful and profound introduction.

DN: Well, looking at the intensity and the length of your UK and US tours with innumerable podcasts and radio interviews in between all of your many public appearances, and imagining you opening up your schedule deep at sea and all of this public-facing activity and seeing our epic-length conversation slotted for today, [laughter] in anticipation of that and wondering, "Will Robert Macfarlane still be alive?" I really wanted to make sure what we talk about and how we talk about it doesn't just slot into the blur of the same questions phrased in the same way, much in the spirit of how you yourself approach language in this book. Given that this is a writing and literature show, I wanted to look at all of the concerns—ecological, political, human, and more-than-human—through the lens of language. I wanted to first introduce you to the terrain you step into today, what conversations have occurred in the space that most of the listeners today will have heard, sort of as part of a sedimentary sort of shared knowledge, whether the many writers that you've engaged with who've been on the show or the ones I consider you in conversation with in some way. To name a few of these past guests: Alice Oswald, Alexis Wright, Ursula K. Le Guin, Natalie Diaz, Amitav Ghosh, Jorie Graham, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Richard Powers, Kim Stanley Robinson, Layli Long Soldier, Max Porter, Cecilia Vicuña, Naomi Klein, Forrest Gander, Ross Gay, Ada Limón, and many others. In the aura of this ecosystem of wordsmiths, let's talk about words, words that can be opposite things, that can be a scrim over reality or in high-stakes political situations—like say right now with Palestine—a way to obfuscate or divert or a means to excuse oneself from engaging with the thing itself, simply if the wrong word is used. The epigraph in your book by Natalie Diaz suggests a desire to get beyond words when she says, "How can I translate—not in words but in belief—that a river is a body, as alive as you or I?" But you emphasize an equally powerful mode of words when you say words make worlds, that they don't just describe, they generate. It reminds me of Cecilia Vicuña talking about the Yaqui or Yoeme people, about how speech creates worlds in this way, an idea that's not uncommon in many Indigenous cultures. Of course, if you want to speak to the dual nature of words, go ahead, but I would love to hear also what you mean by words making worlds and the implications of this aspect of words as generative and not simply as descriptive.

RM: What a first question. Well, let me start with—well, I’ll try three answers to that. So, in theory and linguistic theory, as you will know, speech act theory speaks of what’s called illocutionary or performative utterance, and this is a contested area, but broadly speaking, illocutionary or performative utterance is that which changes the world by being spoken. So J. L. Austin, who writes How to Do Things with Words, which begins this field, gives us the very, as it were, humdrum or everyday example of, "I pronounce you husband and wife. I pronounce you married." This is a speech act in which an individual who has a certain power vested in them utters something. Austin contrasts that to the descriptive mode, which is, "It is raining." This does not cause the rain to fall, it merely describes the fact of the rain. I speak of the illocutionary and the performative in this rather theoretical way because it is the difference between saying that a river is alive in a way that is metaphorical. I think this is what James Scott does, the great anthropologist who published a book called In Praise of Floods just before mine came out, which begins with the proposition that looked at in the long view, a river is alive. It moves, it floods, it shifts. Now, that to me is not a performative utterance; it’s a descriptive utterance, and it’s also really rendered through metaphor. This is "river as alive," we could say. But to say "river is alive," and to mean it to commit absolutely to the difference between "as" and "is," and to commit to the "is" in so doing, is to see the world shift around you. Because that which is consented to by that affirmative, that fully philosophically, ontologically meant affirmative, is radiant in its consequences. So this begins as a book, this journey—it’s not really a book—it’s the last four and a half years that have sluiced and rinsed my life in wonderfully torrented ways. It has been the movement from descriptive to performative, from "as" to "is," and we can perhaps unfold between us what river is alive radiates.

DN: Well, in this book you talk about how the word grammar sounds dry, but hides a great power within itself, that its Middle English usage also meant magic, where a grammar was a book of spells in addition to signifying that which orders the relation between things. You say a good grammar of animacy can still re-enchant existence. "To imagine that a river is alive causes water to glitter differently. New possibilities of encounter emerge — and loneliness retreats a step or two." In that spirit, I want to put us under the spell of your grammar of animacy by hearing the language you conjure and cast forth in the prologue, and to spare you on your tour from reading it, I was given permission to share an excerpt of you reading from the audiobook. The audiobook edition of Is a River Alive? is published by HighBridge, an RBmedia audio brand, who are offering this for us to hear today. Here’s the beginning of the prologue.

[Robert McFarlane read the prologue of "Is a River Alive?"]

DN: We've been listening to Robert Macfarlane read the prologue of Is a River Alive? So the opening to your book, both in its scope and in its music, reminds me of the opening to Richard Powers' The Overstory, in the sense that both establish a frame of time that is beyond a human frame. In your case, we start before humans, and by the end of the prologue, we have been swept forward to not only humans, but to you specifically—you and your children—and the endangered, ailing spring by your home. Both you and Powers are attending to the music of language in these sections, which makes me think of Ursula Le Guin talking about Virginia Woolf’s notion of the wave in the mind, the current that flows beneath the words, that has a meaning beyond words. I’m curious what other ways you consider that help keep human language attuned to that which is not human or not only human and beyond language and semantics, especially thinking about how this book, which visits three rivers in Ecuador, India, and Quebec respectively, I think they also have different grammars of animacy as well.

RM: Wonderful question. It's a set of streams of thought that you have unleashed there. The first is to say the phrase "grammar of animacy" arises from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s work, as so many people, myself included, have found it generative. So the notion here is to recognize that grammar as sedimented ideology in its most sort of rigor-mortised forms can come both to encode and to enforce forms of estrangement when it is, as it were, a grammar of inanimacy—the ways we "it" the world, the ways we objectify the world within language—and that ramifies ethically and indeed politically. If all the living world is "it," then it is available for conversion, extraction, consumption, disposal, and so forth. As soon as we "who" the living world, as soon as it leaps to life in grammar, that is a small but significant step towards reversing or at least adjusting that objectifying relationship. And the second is that wonderful Richard Powers was one of the first people to read Is a River Alive? We've fallen into friendship over the last years and he wrote me an early letter about the book that made me think, "Well, whatever happens now, I can die. I can die happy." [laughter] So you talked about language and semantics, and perhaps we can distinguish between those. So if semantics is broadly the propositional content of language, the meaning that it carries within its [inaudible] polemicizing, declarative modes, maybe the other forms of animacy of affect, they lie in its formal subpropositional capacities and properties. We're very used to this notion with poetry, of course, that is in a way what we read for, what we listen for—rhythm and sound pattern—and then those bigger structures that, in fact, Woolf has a lovely line for what I'm interested in. She calls it "the little language." So she's talking about words and beats and echoes that become activated by repetition across the course of a piece of writing. So the idea of little language and the stuff that lives below the propositional, but sounds on the timpani of the ear, echoes in the abysm of the mind, vibrates the body in some strange way—these are important things to me. So you can hear that in that prologue—the withers, the feathers, the rain, the aurochs, the fox, the sleet, the hail. From the absolute beginning of the book, I wanted to—not teach, teach is too pedagogical and purposeful a word—but I wanted to alert readers to the fact that language would be functioning in other ways in this book. The last thing I’ll say is that we have the local properties of form and style, which we recognize—let’s say a sonnet will possess. But the thing that a sonnet doesn’t, but a 300-page book does, is that there are these bigger-scale patterns that you can build or that your own experiences build. You sort of recognize them almost in retrospect, to me, fascinatingly. So here—the mycelium, the braiding, the multiple rivers, the relation-dialectic between life and death mediated by flowing fresh water, so many others, they embed themselves. I think they kind of incandesce into these networks of something like meaning, but they’re not functioning in a propositional way. Does that make sense?

DN: Yeah, no, I love that phrase, "something like meaning." I think that’s key somehow. Well, the beginning section, the Ecuador section, opens with an excerpt of a speech given by Ursula K. Le Guin called “Deep in Admiration.” The second of the three times that she came on the show, she read this speech, and I’m going to play this longer passage your excerpt came from.

RM: Amazing.

DN: And we’ll use it as a frame from which I have some questions I want to ask you that I think this also raises.

RM: Brilliant.

Ursula K. Le Guin (recorded): The little talk I gave is called “Deep in Admiration.” I heard the poet Bill Siverly this week say that the essence of modern high technology is to consider the world as disposable: use it and throw it away. The people at this conference are here to think about how to get outside the mindset that sees the techno-fix as the answer to all problems. It’s easy to say we don’t need more high technologies inescapably dependent on despoliation of the earth. It’s easy to say we need recyclable, sustainable technologies, old and new—pottery making, brick laying, sewing, weaving, carpentry, plumbing, solar power, farming, IT devices, whatever. But here in the midst of our orgy of being lords of creation, texting as we drive, it’s hard to put down the smartphone and stop looking for the next techno-fix. Changing our minds is going to be a big change. To use the world well, to be able to stop wasting it and our time in it, we need to relearn our being in it. Skill in living, awareness of belonging to the world, delight in being part of the world always tends to involve knowing our kinship as animals with animals. Darwin first gave that knowledge a scientific basis. Now both poets and scientists are extending the rational aspect of our sense of relationship to creatures without nervous systems and to non-living beings. Our fellowship as creatures with other creatures, things with other things, relationship among all things appears to be complex and reciprocal, always at least two-way, back and forth. It seems that nothing is single in this universe, and nothing goes one way. In this view, we humans appear as particularly lively, intense, aware nodes of relation in an infinite network of connections—simple or complicated, direct or hidden, strong or delicate, temporary or very long-lasting—a web of connections, infinite but locally fragile, with and among everything, all beings, including what we generally class as things, objects. Descartes and the behaviorists willfully saw dogs as machines without feeling. Is seeing plants as without feeling a similar arrogance? One way to stop seeing trees or rivers or hills only as natural resources is to class them as fellow beings, kinfolk. I guess I’m trying to subjectify the universe because look where objectifying it has gotten us. To subjectify is not necessarily to co-opt or colonize or exploit; rather, it may involve a great reach outward of the mind and imagination. What tools have we got to help us make that reach? In Romantic Things, Mary Jacobus wrote, "The regulated speech of poetry may be as close as we can get to such things, to the stilled voice of the inanimate object or the insentient standing of trees." Poetry is the human language that can try to say what a tree or a rock or a river is. That is, to speak humanly for it, in both senses of the word 'for.' A poem can do so by relating the quality of an individual human relationship to a thing—a rock, a river, or a tree—or simply by describing the thing as truthfully as possible. Science describes accurately from outside. Poetry describes accurately from inside. Science explicates, poetry implicates. Both celebrate what they describe. We need the languages of both science and poetry to save us from merely stockpiling endless information that fails to inform our ignorance or our irresponsibility. By replacing unfounded, willful opinion, science can increase moral sensitivity. By demonstrating and performing aesthetic order or beauty, poetry can move minds to the sense of fellowship that prevents careless usage and exploitation of our fellow beings, waste, and cruelty. Poetry often serves religion and the monotheistic religions privileging humanity's relationship with the divine encourage arrogance. Yet even in that hard soil, poetry will find the language of compassionate fellowship with our fellow beings. The 17th-century Christian mystic Henry Vaughan wrote, "So hills and valleys into singing break; And though poor stones have neither speech nor tongue, While active winds and streams both run and speak, Yet stones are deep in admiration." By admiration, Vaughan meant reverence for God’s sacred order of things, and joy in it, delight. By admiration, I understand reverence for the infinite connectedness, the naturally sacred order of things, and joy in it, delight. So we admit stones to our holy communion, and so the stones may admit us to theirs.

DN: So one reason I wanted to play the Le Guin, other than just hearing her voice and the wave in the mind of the way she speaks, which is so wonderful, it’s because later in the prologue, from what you read, we arrive at the 16th century and what you call the purging fury to exorcise the sin of idolatry, with vigilante groups fanning out to do so, and much of this activity is water-centric. Spring sites were suppressed and destroyed, holy wells were filled and capped, and those who persisted in making pilgrimages to springs and rivers were arrested and tried. Similarly, in the Ecuador section, you say—speaking of the Spanish conquest in the Americas—"Christian colonialism had systematically punished with burning, hanging, and killing indigenous notions of the landscape as inspirited." This section goes into how people who spoke to or with a river or worshipped a stream found themselves before tribunals where they were condemned to literally have animism whipped out of them. I think of how this legacy is both half a millennia and also a blip in time. One of your children asks you what the title of your new book is, and when you say "Is a River Alive?" they say, "Duh, it’s going to be a short book," which suggests, I mean, this half-a-millennium length, yet still, this sort of instinctual response of your child. You speak of how children instinctively inhabit a world of talkative trees, singing rivers, and thoughtful mountains, and how in children’s lit, a speaking, listening landscape is often a given. Le Guin writes extensively on the connections between the consciousness of children and fantastical literature in this really complex and non-reductive way—not as a childish thing or an interesting developmental phase, but still immature—but it’s something she has deep respect for on its own terms. I’ll definitely point people to, in the Crafting with Ursula series we did on the show, the conversation with Will Alexander, where we explore this gesture that Le Guin makes around fantasy and children’s consciousness. I feel like we still seem to retain some vestige of what has been whipped out of us. Paradoxically, as hard as it is to imagine a river alive for some people, no one has problems imagining a dying river or a dead one, as you stress in the book. Perhaps because water, as alive and sacred, is the long-standing norm, much like Le Guin’s notion of fellow feeling and subjectifying the universe, was also the norm—one that has been banished from science almost like a spring being capped. In our most recent history, I think of poet-naturalists—people who were conducting science, but in the same notebook were writing poetry, sketching the plant they were studying, writing lyric prose with feeling for what they observe and study—and I also think of Le Guin talking about Frans de Waal’s work with bonobos and the resistance of scientists of just acknowledging the kinship they bodily feel when they look at the expressions of these fellow primates. I just wondered if this notion of fellow feeling, if this sparked any further thoughts for you.

RM: So many thoughts, my goodness. How wonderful to—what a treat for me to hear Le Guin read those words, and particularly that phrase, "the great reach outward of mind and imagination that may be required to subjectify the universe, to see trees, rivers, and hills as kin," and here we arrive at the fellow feeling, as it were. Anthropomorphism—you speak of the scientists, the primatologists who are trying to resist the recognition of something like self, the encounter or experience of something like empathy with their subjects, for fear that it distort it, whereas of course in fact it might sharpen it. And anthropomorphism, I often say, at its best and most fluid—and here we are back with Le Guin’s notion of reciprocity—is not just a recognizing of the human in the creaturely, but a recognizing also of the creaturely in the human. So when understood in that, as it were, best form of itself, anthropomorphism becomes the recognition of kinship, of interspecies communication and correspondence. Now, how do we take that idea, which we might find plausible with respect to a bonobo, a primate, how do we move that across to, let’s say, tree—harder there—fungus—harder still—river. Now we enter the other world of Le Guin, as it were, the world of the speculative, the world of SF, of something like fantasy. I realized that, as you’ve seen and indicated, many of the texts that circulate—the second-order texts that circulate in Is a River Alive?—are speculative texts. They’re Stanisław Lem’s Solaris, they’re Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest, they are Richard Powers’ The Overstory, which I think is in many ways a speculative attempt to recognize kinship with forest, with tree. Hayao Miyazaki as well, absolutely soaks with these ideas and these practices. But boy, are they hard. I mean, Lem’s Solaris, which—as those who know the film or the novel will know—features a, what seems to be, a planet-sized sentient ocean. So it really is an attempt to, as Lem puts it, open a plausible line of communication with, in this case, an ocean, a vast body of water. Well, how might we do that with rivers? How might we build an ethics or a politics out of them? These are immensely difficult questions, and I certainly don’t come to any conclusions around them, but I do open them. I think that sense of opening, which is so important to the closed self—by the closed self, I mean the kind of, what does Fredric Jameson call it? "The windless solitude of the monadic ego," I think is one of his phrases for it. [laughter]

DN: I love that.

RM: Yeah, it’s strong and it’s always stayed with me. And something about that idea of the self shivering in its Cartesian garrett, but which is also a fortress. Nothing can come in, nothing can go out. We’re skull-contained sentience and that’s it. Well, that isn’t the world I know. It’s not the world Le Guin wrote of, though it’s a world that Le Guin wrote against. River shows us process ontology, as distinct from substance ontology, like no other force on Earth. I think water relates, it relates in two senses. It speaks story, carries story, and it joins, it connects. So the beginnings of—what does Le Guin call it?—a recognition that nothing is single in this universe, to open towards that and then to again assimilate and irrigate systems, not just self but political, social systems, with the recognition of entanglement and whatever lies beyond entanglement, that is the work of river, as I understand it. River stands there as all the forces that open us in these ways.

DN: Well, the reason why I mentioned liking you saying "something like meaning" is because I feel like it recognizes this reciprocity, but also recognizes our limitations of understanding simultaneously. Like I think of lines in the prologue: "Rain-fed, the spring’s stream surges seawards: gravity at work, or something like longing." Also, "The spring, as it has always done, organizes existence around it, exerting something like will on the land." I love the "something like" because it feels like there’s a humility and a stepping back from the capacity of language to capture, and somehow, by stepping back and saying something vague in a line that’s otherwise very specific, allows it to capture something. It made me think of something that you wrote—that you believe primary encounter creates metaphysics much in the way a river produces a mist—which made me think of Leanne Betasamosake Simpson in her book Theory of Water, that for her, theory is kinetic and embodied and begins with something kinetic. I guess I wondered if that brought up any more for you about, well, about any of this, about theory, about stepping back to capture. [laughter]

RM: Well, stepping back to capture is exactly what I don’t think we should be doing. Capture is a verb.

DN: It’s a bad word.

RM: Yeah, I really abhor, actually, and photographers speak of "the capture," and I think there’s something really problematic in that notion.

DN: I do too.

RM: And the stepping back as well, I think if I’ve learned anything from water, it’s that we are always in the flow, and even when, as writers or capturers or analysts or critics, we think we’re dry-footed on the bank, we’re not. We really aren’t. Then Leanne’s book—I mean, she and I, neither of us, I think, knew the other was writing the book—it’s a wonderful book. There, exactly, theory is not that which is abstracted. To use another, actually, term from water management, abstraction licenses are what are sold to determine the quantities of water which can be taken from the system, used. It’s a beautiful sense of theory as kinetic, as always embodied, as always in motion, dynamic, and volatile. But the third thought—and perhaps the biggest one—that you put into my mind with that brilliant noticing of something like the doubling of it. I remember when I was editing the prologue for the 794th time that I realized that doubling, that repetition, and normally I would hook out a repetition like that, but I thought I would keep it in exactly for that sense of the withdrawn nature of the water, that what I was doing was always going to be a best fit and not a match. So I thank you for noticing it. And the thought that it leads me to—and I’ll end after I’ve opened this up to you, David—is of Édouard Glissant and his notion of the right to opacity. I’ve only really recently, the last few days, started thinking about this. Someone mentioned it to me. Of course, "Is a River Alive?" is full of questions of rights. Should rivers have rights? What are the rights? Rights negotiate relations. But Glissant’s right to opacity can be summarized as the right not to be grasped. He’s thinking specifically about, shall we say, Indigenous or highly localized knowledge systems, regimes of perception, forms of seeing and being—that’s probably the best of those three phrases for what he’s talking about—which resist epistemic attempts by autarkies to pick them up, absorb them, and in so doing translate them out of their worlds, out of their worldings, and into the dominant discourse. So the right to opacity—and here’s where the river flows forwards and back into our conversation—is the right not to be fully understood. I hope that the book recognizes both the right to opacity in the ways of being and seeing of some of the communities with whom I’m in correspondence and contact, and also the rivers themselves, because boy, do they remain opaque. [laughter]

DN: Yes, I think it succeeds just miraculously. I actually think it is a miracle of success in this regard.

RM: I’m glad. Can I just mention one example of that right to opacity from a sort of human-social—so I write in the Ecuador section, you may remember, about what’s called Kawsak Sacha, which is the declaration that the Sarayaku people of the Ecuadorian Amazon offer as part of the defense of their land, the Bobonaza River, and the rainforest that surrounds it. And it’s an attempt to fend off and force off repeated—in effect, paramilitary—extractive incursions over 30-plus years, but going back all the way to the New World colonization of the Spaniards. But it’s a rights declaration, but it names and describes the forest and the rivers and the people as an intelligent, sentient, and conscious being. So we sound like we’re in the world of Stanisław Lem there, but really Stanisław Lem is in the world of the Sarayaku, for whom this is a necessary translation into language which might be understandable by non-Sarayaku readers. So they do that act of translation, and they call it Selva Viviente, the living forest. But what they refuse to do is to allow it then to be translated across into the conventional protective designations and discourse of Western conservation, which would not recognize the forest itself as living and conscious and sentient, or the river. They say, "You can take this so far, but we reserve the right to opacity," the refusal to be grasped by big or target existing knowledge systems, Western conservation discourse, let’s say, or the nation-state governance system. I’m very particular in that section of the book to maintain the respect of that right to opacity and recognize their refusal to be translated across.

DN: Well, we have a question for you that extends this question even further—and even deeper, I think—into the very mysteries of what a self is. This is from past Between the Covers guest Richard Powers. He appeared on the show to discuss his Pulitzer Prize–winning book The Overstory, but in a very unique way for the show. In the morning, we did a podcast version at the local radio station, but then later that night, I also interviewed him at a ticketed event at Revolution Hall here in Portland. But because we were talking twice in the same day and I wanted it to be fresh and alive both times, I came up with two entirely distinct lines of inquiry, and both of them are available in the archives. I think they ask and explore many of the questions we're raising today, so they would be good places to go after this. But through the lens of trees in the case of that book. Here's a question for you from Richard.

Richard Powers: Hello, Robert. I am so grateful for this book and so lucky to be alive at the moment when you wrote it. It truly lifted me up and made me want to engage the world with everything in me. One of the lessons that you learn from your spiritual guide, Rita, is not to put people over here and rivers over there, but to think of them as deeply imbricated. That vision of interbeing put me in mind of another great writer about deep time whose mantle you now wear. I’m talking about Loren Eiseley. In his essay The Flow of the River, Eiseley says, "If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water." But there’s a less famous sentence in that same essay that goes even farther. This one: "As for men, those myriad little detached ponds with their own swarming, corpuscular life, what were they but a way that water has of going about beyond the reach of rivers?" So my question is, having made the case that rivers are alive, can you get behind the idea that living things are themselves the extensions of rivers in the run of time?

RM: Well, thank you for—you pulled a fast one on me there, David. [laughter] How incredible to hear Richard speaking. I suspect from the Smoky Mountains, deep in the forest there, speaking directly to me. The last time I saw Richard, he handed me a piece of those forests—a maple wood bowl turned after the wind felled the tree—and I said to him immediately, and there is a relevance to this story, it had the most beautiful spalted grain. And spalting gives you these dark, sort of blurred shapes that paradoxically come to resemble the things that we see in them, of course, as pattern recognition functions in that way. The first thing I saw in the grain of that bowl was the blurry outline of a salmon to my eye. That salmon was no ordinary salmon. It was the sonar image of the first Chinook salmon to make it upstream of where the Iron Gate Dam had once stood on the Klamath River—a dam that had been there for, I think, 60 years before its dismantling last year, 2024. For all those years, it had blocked the passage of migrating salmon. Then, two days after the dam was fully dismantled, that sonar caught that blurry, lozenge-shaped image of the salmon making its way upstream. The salmon is a water body. The Klamath is a water body. Astrida Neimanis tells us water seeks a body, and sometimes that body is river-shaped. We call a river a river, but of course, if we think of it only as its main trunk, we mistake the tree’s trunk for its branches, its leaves, its roots, the mycelium it connects to. The river also is this great compound gathering. Water seeks a body. Sometimes that body is river-shaped, sometimes it’s salmon-shaped, and salmon is returning marine nutrients way upstream where it will feed the forest with its own bones. So there again, life is moving in other bodies, carried by and within and without by water. We are water bodies, three-quarters of water. That phrase “water body” I think is such a strange one, because we so rarely turn it back upon ourselves. Water comes as lake and as puddle and as pond and as snow, ice, hail, sleet. Moves as groundwater. Huge sky rivers work uphill against gravity to swell the clouds that then swell the rivers. So yes, Richard, the answer is that, you know, we live and in a way have always lived in the hydroscene. We just haven’t seen it sufficiently. So just being reminded simply that humans are part of the water cycle, flowed through and flowing on, feels to me absolutely essential. Trees, rivers of sap, moving and moving moisture from the ground up to transpire through their leaves. All of us carry fresh water within ourselves. But how rare it is as well—it still smacks my gob, as we would say in England—that 0.05% of the world’s water flows in rivers. They are rare and they are fragile.

DN: One thing I really love about your writing in this book, which feels like an act of fellow feeling that disrupts this binary between the human and the more-than-human world, is counterintuitively the way you describe humans. In each of the sections, you assemble a different traveling group for the expedition at hand and also have certain people you’re going to encounter. You describe each of them in a really multifaceted way. Sometimes it feels like you describe them as if you were a bird or as if you were describing a newly discovered bird. But you yourself are in the study, so to speak, in the maelstrom of the description, which can’t help but be relational. There’s a certain love in your gaze, not enacted through portraying people in their best light, but from every angle and context, with all their ways of being included, including ways people can be off-putting. Much like you’re often visiting wounded land, many of these people are wounded too. The first encounter like this might be perhaps the cantankerous man who lives alone as a sort of sentinel high up in the Ecuadorian cloud forest. But let’s take a moment to hear about the people you decide to gather around you and share the journey with in Ecuador. Why you’re visiting this specific forest and why you’re visiting this specific forest with these specific people?

RM: So I gathered a group, a group formed around me of which I was part, to travel to this cloud forest called Los Cedros, the Cedar Forest, in the northwest of Ecuador. I was drawn there because a cloud forest is a river maker. I wanted to reach the headwaters of a river that shouldn’t exist, a river called the Río de Los Cedros. The reason that river and the cloud forest do exist is because in 2008, Ecuador recognized the rights of nature in its constitution—the rights of rivers and forests to respect—very much a reciprocal property or quality—to exist, to flourish, to persist. In 2021, just as mining companies were preparing to abolish this forest, which has probably self-regulated for more than a million years, and its rivers, to slurp out the marrow of the mountain in the form of gold, an amazing constitutional court ruling was handed down, which drew upon those rights of nature articles and was of such power—because constitutionally guaranteed—that it compelled the eviction of those mining companies. So we traveled up into this cloud forest with every step taken in the factual, in the counterfactual—the factual, the living forest, this place of ultra-life, and the rivers that flow from it; the counterfactual, the forest that shouldn’t exist, the rivers that should be running red. With me were two of the three judges who had handed down that ruling but who had never met the forest because the ruling and the court hearing were carried out during COVID. But with me also was a human rights lawyer called César Rodríguez Garavito, who's become one of the leading lights of the rights of nature movement. Remarkable man. Sound and field recordist and multi-instrumentalist called Cosmo Sheldrake, who gave me new ears to hear with a field micologist called Giuliana Furci who has written the two definitive field guides to the fungi of Chile and who is also, yeah, one of the most sort of supernatural people I’ve ever met, I think. [laughs] So we gathered and we climbed and we ascended and spent time up there. Yeah, it was a powerful place.

DN: Well, as you said, some of the people who come along on this trek are the lawyers from Colombia who were instrumental in saving the land from mining but who hadn’t seen the forest they helped save. We have two similar questions for you about the legal approach. I debated whether to play them together as one or not, but I decided to play them separately. The first is from a past guest of the show and a friend of yours, the novelist Alexis Wright. Since she was on the show, when we discussed her latest book, Praiseworthy, that book has gone on to win Australia’s most prestigious awards—the Miles Franklin and the Stella Prize—and the UK’s longest-standing literary award, the James Tait Black Prize. The judges for the Queensland Award, which it also won, call it an extended elegy and ode to Aboriginal storytelling, lore, and sovereignty. Stephen Sparks says, "Alexis Wright's Praiseworthy should be the last novel ever published. It’s the ultimate expression of what fiction can do, a marvelous beast that gobbles and spits up all genres, whispers and screams and moans in all registers, and the vision of our world that it casts back in its distorted funhouse mirror seems more real than piddling reality itself." So here’s a question for you from Alexis.

Alexis Wright: Dear Robert, I’m sending you very best wishes and congratulations on the publication of your marvellous new book, Is a River Alive? Your work, your voice, is vital to people across the world. You help us to see the world better. Thank you for being the special writer that you are and for everything that you do in the world. It is a great honor to know you and to be your friend. In the Aboriginal world of this continent, we say that if you look after your traditional country—meaning our ancestral land—then the land will look after us. Mark Coles Smith, the Nyikina narrator of a wonderful new ABC TV documentary about the Kimberley region of Australia, explained this concept while talking about the mighty Martuwarra or Fitzroy River, which is one of the world’s most pristine free-flowing river systems, stretching 733 kilometers from the East Kimberley to the coast of King Sound, a large gulf in northern Western Australia where the river opens to the Indian Ocean. While Mark was saying that we all have to just appreciate what we’ve got, not take it for granted, he also said we have got to share the guardianship and custodianship of the river. "We keep the river alive. The river keeps us alive. That’s the deal." That’s what Mark said. "That’s the deal." It seems to be a very simple deal and should be easy enough to understand. But as you know, when you look at the many levels of deep crisis happening across the world right now—our only home—now a global warming catastrophe, where every day the deeper and more dangerous this emergency becomes, the more humanity, or the most powerful world leaders, are distancing themselves from understanding this basic concept of the deal, of safeguarding the interconnectedness and interrelationship of the world, so that the world will or can continue looking after us. My question to you is something that I think about: I feel that we need strong legal recognition and protection for the entire world, to ensure our planet is protected and that it has the right to exist and thrive, rights that we expect for ourselves and for our existence. Do you think we should be working towards this urgent problem and at a planetary level right now in the hope of keeping our planet alive? Thank you, Robert.

RM: Goodness me. David, I'm practically in tears here. That's Alexis Wright.

DN: It is Alexis Wright.

RM: My friend and correspondent of I think six, seven, eight years now, we've never met. There her voice is speaking to me here out of my place when I'm feeling displaced, and her wisdom and her voice, like that of Richard, just immediately re-grounds me. So I thank you so much, David and Alexis and Richard, for making that possible. What a question then. I know that Alexis has written of the Narjong, which is the gathering of elders who perform a water ceremony. This was carried after the so-called Darling River die-off, fish kill, in which probably a million fish died about five years ago. This ceremony, this gathering of elders to perform the water ceremony, that Narjong, has probably—Alexis told me, has written—has gone on for about 120,000 years. So there’s something in that idea of an ancient assertion told as a story, sung as a song, taking the form of a gathering, a ritual that is passed on generation to generation and re-recognizes, re-recognizes the right of the river to live, the right of land to flourish. Because, of course, that’s the deal. When the river thrives, we thrive. When country thrives, we thrive. It seems like one of the most spectacular forgettings of our time, of this terminal stage capitalism, this entropic Anthropocene into which we seem to have locked ourselves. No matter how hard we struggle, we only seem to tighten its bonds upon us. How can we have forgotten this? There are reminders of it that stretch back 120,000 years. So how do we perform a Najong for the planet, as a species, as a people? It is simply the most pressing work of the time. Alexis writes better than I think almost anyone I know about story. She and Richard share a great conviction in the power of story. Both of them, of course, know that bad stories have been told very well by bad people. Story itself is not automatically a virtuous form, but they do know the power of story to heal, to gather, to summon, to beckon, to reckon. The work that they have done as writers is some of the most powerful storytelling that we have. So legally speaking, yes, I think rights are stepping forwards as the best-fit model for a declaration, a recognition of the subjectivity of the living world. I refuse to speak of the environment these days. It’s such a chilling externalizing and technocratic word. It’s got us nowhere, really. We should only speak of the living world, the natural world. Nature, if that nature includes us. Yeah, yeah.

DN: We have another question that is—

RM: Who’s this one from? [laughter] Wait, this one’s from Samuel Taylor Coleridge, speaking from beyond the grave.

DN: It is. This was very difficult to get, but we... [laughter] So we have another question that’s a reiteration of Alexis’s question in a briefer form. I’m going to make an omnibus question with it, with some thoughts of my own. So we’ll play the question and then afterwards I’m going to speak before you answer. This is from past Between the Covers guest, Amitav Ghosh. We spoke about his book Smoke and Ashes, which is part memoir but part deep engagement with colonial extraction, but it’s also a book that centers and posits plants as protagonists, as powerful agents within history itself. So first I’ll play Amitav and then I’m going to add some thoughts so we can stay with this question of rights and legality.

Amitav Ghosh: Your book is, among other things, a manifesto for the rights of nature movement. Do you believe that this movement could lead the way in reimagining the relationship between the human and more-than-human worlds?

DN: So to continue with Amitav’s question, in an interview that you gave in the Hindustan Times, you say, “Why should a company founded two days ago have rights, but not a river that has flowed for tens of thousands of years? It’s a form of socially normalized madness.” And one of the things you explore quite extensively in this book is the rights of nature movement that Alexis and Amitav raised in their questions as one example of a multi-headed strategy to address the normalized madness. Outside the book, you’ve written about the city of Toledo, where the phosphorus runoff had so fouled Lake Erie that the city lost drinking water for three days at the hottest time of the year. And so, appalled by the lake’s degradation and the failure of any action, they drafted a bill of rights for the lake itself. You call it an act at once both hopeful and desperate. And you portray many of these hopeful yet desperate acts around the world in Is a River Alive? But you also portray the limitations of some of these efforts. On the one hand, you’re literally hiking through a cloud forest still there because of these efforts, and you cite the field biologist Mika Pech and the British-Peruvian barrister Mónica Feria Tinta when they described the 2021 Constitutional Court intervention in Ecuador, “as important a ruling to nature as Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man to our own species and as comparable to the turning point in the history of human rights as in 1948.” Yet, you also portray people in India calling a police station to report a murder—the murder of a river that has been declared alive—and the cops not doing anything. Or again, in Hindustan Times, wondering about this deep discrepancy between the religious recognition of rivers as sacred in India and the ecological devastation of those very same rivers. Outside of the book, you’ve also spoken about how you are less enamored with the seeking of legal personhood for rivers versus other efforts within this large umbrella. I wondered if you could just speak a little more granularly to where you are excited and where you are wary, where—like with words themselves—efforts could be purely performative and symbolic, or even a method to not do anything more, and where we might push the symbolic more effectively into the material and into material change.

RM: Brilliant. Yeah. Thanks, Amitav, and thanks, David, for that beautiful and spooling of possibility and consequence and limit from Amitav’s question and indeed Alexis’s. Yes, I was, as you were, even before you began to conclude, I was thinking, “Well, here we are back with the performative.” So it’s worth saying that many—indeed, I would say the majority—of rights declarations, rights of river declarations, rights of forest, rights of nature declarations, they are performative, which is to say that they have no purchase or ratification within existing legislative systems. They don't have power as we would understand it as exerted by law and regulation. However, when I say they are performative, I don't mean that they are trying to virtue signal that they are trying to demonstrate their own goodness or infinness of intent, I mean it in the linguistic sense with which we began, the speech act theory sense with which we began. They are trying to be performative in the sense of “saying makes it so.” That by declaring, by irrigating the language and the structures of resolution, of declaration, with legal pluralism, with Indigenous cosmovision, with ontological claims about the being as a verb and the rights in the sense of inalienable, pre-existing rights as a best-fit name for the planet, they’re doing disruptive, de-anthropocentrizing, powerful forms of imagining otherwise. So at their best, at their performative best, they imagine otherwise in ways which are very consequential. I wonder if I can just actually read you two short sections, very short sections, from The Innu Declaration of the Rights of the Muteshekau-shipu River, so that people can hear what happens when the vision of the river as a living entity meets the grammar of the declaration, as it were.

DN: I love that.

RM: So here it goes: "Whereas, since time immemorial and long before the arrival of Europeans, the Innu people have occupied, managed, used and frequented the Nitassinan homeland, of which the Muteshekau‑shipu or Magpie River is a part, practising a traditional way of life and surviving on the area’s fauna and flora. Be it resolved that the Innu Council of Ekuanitshit declares that as a legal person and a living entity, the Muteshekau‑shipu, Magpie River and its watershed have fundamental rights in accordance with the beliefs, customs and practices of the Innu of Ekuanitshit." So we hear the language of, let's say, the Declaration of Independence, whereas, be it resolved that, let it be known that, etc. But into that flows an ontological claim of great wildness and radicalism. The river is a living entity, in accordance with Innu lifeways and the river has fundamental rights. There is a collision going on between form and content. You can find this all over. At some level, what the rights work is doing now is an atritive work. It is bashing away at deeply buried keystones of anthropocentric human systems, the deep codes that govern economics, law, environmental regulation, so Roman law, and here it really does go back to Roman law because Roman law provides the foundation of what then gets exported as an in effect to colonial management ideology around the world. Roman law distinguishes between persons and things, and persons as roman law understood it could not owned; they could be property owning, of course, slaves, ensalved people, in Roman culture were designated as things and not as persons. But absolutely not and absolutely not designated as persons were land and water in effect. So the concept of water was assimilated as part of land and thus was made an object of property, whether that be individual rights or common rights. Certainly, the notion that it might be rights-bearing was completely preposterous. It was outside the consciousness of that system, and that system then became deep coded into inter-property law. William Blackstone in the 18th century absolutely consolidates that and water becomes an ownable thing, certainly not a person. Yet we have naturalized to the point of invisibility the fact of a corporation having rights. So to close with just some granularity, I absolutely do not want rivers to have the rights of corporations because corporations kill rivers and rivers are life-giving forces so we need to sort of reimagine what rights mean here and we need to not read across from corporation to river and the second is yes, it's important and I think useful to distinguish between legal personhood by which is meant the ability to have standing in court, that's what that definition of personhood means and rights which are inalienable and pre-existing, and I am much more drawn to rights and feel that personhood should be, as it were, separated off. But upstream of both of those things is the idea of being, of life, of aliveness. That is the spring, and the law is the rapids downstream. So how do we decide what is alive and what is dead? How do cultures, systems, and power describe, fortify, and adjust what Jacques Rancière calls the distribution du sensible, the distribution of that which is audible, visible, and at some fundamental level, alive. People fought beyond that partition of the sensible as well as rivers which have for a long time lain confidently outside it within Western systems.

DN: One of the ways you make connections as you meet people in "Is a River Alive?" is by gifting books to them. This was a major theme in my conversation with Madeleine Thien about her book, The Book of Records. Both the risks people take on behalf of art with the Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu carrying over 1,000 of his poems on his body as he's displaced during a massive civil war in famine or Hannah Arendt escaping over the Pyrenees, desperate to be reunited with her suitcase, which contains the only copies of Walter Benjamin's final writings, but also the gift of books and friendships that defy time and space through books. When you arrive at the station high in the cloud forest in Ecuador, before venturing even higher with a smaller group, our cantankerous sentinel there speaks of having just read Le Guin's Dispossessed, and you gift him a copy of The Epic of Gilgamesh, a story written 4,000 years ago. In your book, Underland, you say that what we're doing to the earth is disrupting deep time and that things far below are surfacing as a result, which makes me think of the hunger stones you write about carved centuries ago into the banks of rivers as hydrological markers, where if a drought is severe enough, if the water drops low enough, you will see one of these stones and what is written on it, including famously on one of them, "If you see me weep." But you also on the flip side of this resurfacing, of this harrowing notion of resurfacing, talk about moving into the underland of a word to spring it anew into strangeness which brings me back to Gilgamesh and the story of the survival of this epic that it may have survived not despite disaster but because of disaster that when the library of Nineveh was destroyed in a siege thousands of years ago, the fires baked the clay tablets that this story was carved into. A story that likely was written with a reed from a river as the stylus. You've talked about all of this outside of this book. And I suspect you gifted this book more primarily because of its narrative. Of the three ecosystems you explore, Ecuador is the one for me that feels like the most fully living on its own terms, much like how I imagine the forest in the Epic of Gilgamesh, so alive that its main occupant in the epic is this cross-species powerful forest spirit that some call a demon. When you say that cloud forests are less than one half of 1% of the Earth's land, yet contain 15% of the known species on Earth, that they have been possibly a continuous self-regulating forest for as long as one and a half million years. When you say the cloud forests in the river and Ecuador are co-authoring each other, I think also the cedar forest in Gilgamesh being vibrant like this, the forest and the forest spirit co-authoring each other. I just wanted to hear for a moment, maybe you could talk about why this of all books is the one you would gift as you enter this place and this space. What was it about The Epic of Gilgamesh that you would carry it here and then offer it to someone else?

RM: Well, first of all, I'm a massive Gilgageek. [laughter] It won't let me go and I won't let it go. What does Rilke say? He says, "It concerns me." In many senses, I think it concerns me too. I will just say that the only tattoo I have and will ever have is the two cuneiform symbols from Gilgamesh that together make the word river. They sit just on the inside of my right wrist, just above my pulse, above my river, the river of my body. So that's, yeah, it's a pretty thoroughgoing, inked-on relationship, but just to lock one, just to make explicit a detail that explains, I think most obviously why I carried The Epic of Gilgamesh to José DeCoux, the guardian of the cedar forest in Los Cedros is that Los Cedros means the cedar forest and I still remember the moment in early 22 when I was deep in Gilgamesh at the time and I suddenly realized that the name of the forest that had been saved by this rights of nature ruling was Los Cedros, the cedar forest. So here we had two, we're back to the factual and the counterfactual, we had a mythic cedar forest that was destroyed by Enkidu and Gilgamesh in what I sometimes call the first of the tellings of all of the fellings, the first act of ecocide, this wanton destruction of the entire forest right to the banks of the Euphrates. On the other, we have another cedar forest, a contemporary one, which amazingly is a different story has been told where the mining companies who are Gilgamesh and Enkidu have come to the brink of the forest. Then there they are repelled by a force field of moral imagination taking the form of law that drives them away. So from the very beginning of my acquaintance with that forest, it vibrated between the mythic and the actual in these extraordinary ways. José DeCoux, then this grumpy, shambly, rude, hazing, bearlike man [laughter] to whom the book is dedicated because he passed away just as I was finishing it in 2024. But for thirty-five years, he had been the Humbaba of that forest, the forest guardian spirit who had just understood the miracle of its life and moved there in a tent and gave up almost everything to attach himself to that forest and become its defender. So Humbaba is the OG of, like, water and forest guardians. Then so many of them begin to recur in the book. Those echoes and rhymes across 4,000 years—4,400 even, if you go right back to the first Sumerian cycle of Gilgamesh—so strong. So I took it up to, I actually gave a copy to José in Ecuador, to Yuvan in Chennai, and to Rita in Nitassinan in Quebec, and each of them, something remarkable resonated out of that giving, and that speaks of the gift—the gift gives on, as Lewis Hyde tells us—but also, I think, of that myth of Gilgamesh itself.

DN: Well, the move into the second section and the second ecosystem that you explore couldn't move farther from the self-regulating forest. The rivers around and within Chennai, India are dead. The water, without any dissolved oxygen, is unfit for life. There are no fish. The effluent from massive pharmaceutical companies is only one of a myriad of disastrous circumstances there. You visit an industrial area where people have to build their homes from radioactive bricks. It's just one example. When you participate in a program to help turtles successfully lay their eggs on the beach and for the hatchlings to get back to the ocean, you must walk through immense amounts of trash. “There among shards of funerary clay pots, charred sticks, human turds, and plastic bottles, we find two more intact turtle nests.” Yet thinking of the epigraph to this section from the Indian historian Bhavani Raman that goes, “Before landscapes die, they first vanish in the imagination.” Somehow, contrary to this, in this most dire iteration of how degraded a watershed can become, imagination has not vanished. You largely spend your time there with a young naturalist, educator, writer, and children's book writer, Yuvan Aves, who himself comes from a deeply violent and abusive family situation, who came to this work full of his own suffering and became particularly interested in species that most people consider pests, and also detritivores that feed off of dead organic waste. He becomes someone who mobilizes people from a young age to sort of disrupt the untenable status quo around how we are treating the water and the land. I imagine detritivores as a sort of decoder key into why you are in Chennai, why you are in Chennai with Yuvan, because of the way that they turn death back into life. But tell us in your own words why we are in this watershed and why we are in this watershed with this specific person engaging with it.

RM: Well, you've done a brilliant job again of unbraiding, separating out strands that gather in Chennai. And, yeah, detritivores are a class of generally overlooked and despised organisms—so millipedes, earthworms, ghost crabs, fiddler crabs—who turn waste, they metabolize what looks like waste into presence again. They, I suppose, metaphorically take death and turn it back into life. In that sense, they echo with the fungi of Los Cedros, of Ecuador, who are continually metabolizing what seems like death through the process of rot, which many of us instinctively shy from, back into a form of life-giving nutrient. There's a dream I have in Ecuador where Juliana had lost her father very shortly before coming to the forest. We were always surrounded by leafcutter ants. I have a dream where the leafcutter ants become, in my mind, griefcutter ants, and they're snipping out and carrying away in these myriad troops little bits of grief—Juliana's grief—as she slowly comes back to life. I think that those griefcutter ants are a version of the detritivores who slowly metabolize. Yuvan is a detritivore. He grew up in conditions that would drive almost any of us, I think, to what Yuvan calls a small self. That is, the kind of retreated self who suffered such harm. He knew great love from his—and knows great love from his—mother as well. He also lost his sister, Yolini, his younger sister, when she was sixteen. But it was the violence of his stepfather that really caused him to flee his home. And he ran inland from his home in Chennai, and he's sixteen at this point. He ran to a school called Pathashaala, which is a Krishnamurti school. There, he underwent what he and I both call crystallization. We know so little about the chrysalis. It's one of those miracles of insect life. The chrysalis is formed, and then this remarkable liquid, the cells reformat themselves as a liquid and then recompose as butterfly or as moth. It's wild, and it's a bit like Schrödinger's cat. You can't really understand the reformatting that's happening unless you cut the chrysalis open, and then the reformatting stops. But Yuvan crystallized in this school, and the crystallism that he underwent was participatory with a much wider web of life, or “ Palluyir,” to give the Tamil word that he introduced me to, which also gives the name to the nonprofit that he founded, Palluyir. The reason we came to know one another—and I don't mention this in the book—is that as he was recovering, with ants and fungi and toads and snakes and teachers and peers, four or five books became very important to him. One of those—and I have no idea how it got to Pathashaala—was a battered paperback copy of a book of mine called The Old Ways. And Yuvan read that. That caused him to reach out to me in, I don't know, 2019, 2018. We became friends. So when I started thinking about water, knowing how deeply committed Yuvan was to just futures for water, what a remarkable kind of presence—luminous, radiant presence—he was, with this great enlarged, inclusive sense of self, constellation not a circle, that I knew I wanted to be with him and see water through his eyes. That's why I went. And I'm just going to fill this bottle with water. Just hold on very briefly. This is one of the most amazing interviews I've ever done.

DN: Oh, thank you. [laughs]

RM: You've pulled a number of extraordinary heists and also the best kind of ambush, and also just—yeah, the care and the vision and intelligence of your questions and conversation is off the charts, different order of magnitude.

DN: I mean, I have all those people I named at the beginning to thank for getting me into the same universe of concerns to be able to have this conversation with you. So.

RM: It was brilliant, absolutely brilliant.

DN: Well, thinking about Chennai and turning death back into life, I wanted to use that as a way to talk about hope. If there is hope, it seems to me it is in how quickly something can return when we let it. One of the examples you give in the book is the process of daylighting rivers that we've entombed beneath our cities. You point as one example to one in South Korea, a daylighted river that becomes both socially and ecologically transformative, a park for social gatherings at lower temperatures in the city because of the river and at lower air pollution. I also think of two things side by side, two, one in the book and one outside of the book. In the book, you talk about how there are 50,000 dams on the Yangtze River catchment alone, which just seems utterly impossible, but it's also true, and that those dams have impounded so much water that it has measurably slowed the rotation of the earth. But then outside of the book, and you've already mentioned this today in our conversation, the largest dam removal project in US history, which is in my bio region in Southern Oregon. The four hydroelectric dams removed and the restoration efforts made in a collaborative effort between multiple native nations that live along the river, the states of Oregon and California, the dam’s owner, several nonprofits and more. Within two weeks of the project being completed, the Chinook salmon had already returned to the upper waters of the Klamath for the first time in a century. The speed of the return and the memory of the fish makes me also think of the turtles in the India section who have been voyaging the ocean for 120 million years, long before India and Eurasia crashed together to form the Himalayas. You often speak of Mariame Kaba's notion of hope being a discipline. I confess I have a vexed relationship with this word hope, but also a vexed relationship perhaps that it can be conjured through discipline. I'm confident that there are many people motivated by hope, but I guess I feel motivated by other things and think more of hope as an emergent quality through getting involved in something rather than how one gets involved. This could just be particular to me, but I think of when Greta Thunberg says, “Once we start to act, hope is everywhere. So instead of looking for hope, look for action, then and only then hope will come.” But either way, when we get out of the way, and allow these rivers and their creatures to behave as they want to, the swiftness of the return is incredibly energizing, I think. I wondered if you could speak to any of this, hope, motivation, fighting for a future that we probably won't see ourselves. Talk to us about any of this.

RM: Before I do, I just want to come back to you and just ask you to fill out that distinction between hope and action, or a little more about your dissatisfaction with the word hope. It's a word to be wary of because we know it could be used blindly and we know, yeah, anyway.

DN: I guess the notion that we must muster or steal ourselves through discipline to generate a hope that we're not naturally feeling, I was thinking of Greta again, when I'm out doing something in a collective way, the hope comes, maybe it's sort of like the mist on the river when you talked about primary encounter creating theory. Like to me, the hope is secondary to the being together in the act. I know there's it's a conundrum, right? How are you going to act if you don't feel hopeful? [laughter] Then at the same time, and I do think it's self-reinforcing, the more you act, the more connection you have, the more, if hope's the right word, I don't want to derail us to my own weird idiosyncrasies, but I would be interested in hearing a little bit for you about deep time in the future and motivation and whether that motivation is hope or whether that motivation is just the witnessing of a salmon two days after a dam is removed. That is suddenly where it's supposed to be, having not been there for just generations and generations of fish.

RM: Yeah. Yeah. It’s about the most hopeful thing I've seen in the last, pretty hope scant few years. I think that that's not a sentimental tier-streaked vision of the single fish making its mighty journey against the flow. It's the sense of that fish as metonym for this vast watershed of discipline and of hope. So maybe it's about—well, sidebar, I had a really long conversation with Terry Tempest-Williams, the great Terry Tempest-Williams, one of this continent's great writers about land and relation and people, nature. She doesn't care for the word hope at all. I think she thinks grief burns hotter and deeper, and rage is stronger and more purposeful. So we had an interesting exchange around that. Then I will say maybe it's about a sequencing, I suppose by hope I mean something like imagining otherwise, so in the case of the Klamath, no living generation could remember what that river was like before it had been dammed. There was an intergenerational inherited cultural memory of the time when it had the third-greatest salmon run on the Pacific West Coast when the Yurok tribe were a salmon people with salmon food sovereignty and salmon food security. It descended in the forms of story and poem and narrative and image, which are very powerful forms of descent and knowledge transmission, but no one living could remember that. So out of that web work, that string basket, string bag, to use Ursula Le Guin's famous example, that carries story and stuff within it, emerged a future memory, if we can call it that. Maybe hope is about future memories, something like this, of an undammed Klamath, what that might mean, not just for the river, but for everything that the river enlivens. That radiating aura of enlivenment reaches the wetlands, and then it reaches the prairie itself, and it reaches the forests, and it reaches the people and the well-being of the people. It's not a simple story. There's a great, great J. B. MacKinnon long-form essay, which anyone who's interested in the Klamath, I would commend, because it goes way upstream and delves into the really gnarly and curdled politics of a lot of the curdling being done by Trumpism that he encountered up there, which he wasn't expecting. So, hope: first you imagine otherwise, what would it look like if? What would it mean to, and then you organize? So for me, maybe hope is the uncertainty of possibility, adaptation—I guess of Rebecca Solnit’s powerful thinking in this area—then it's the recognition of the necessity of organization and labor. No surprise that it took twenty to twenty-five years for that broad alliance of river imaginers of Klamath otherwiseers to deliver. But actually, it only took 25 years.

DN: I know. [laughter]

RM: Now, we'll be a year on in August and from the end of the fourth dam coming down. I'll end with this thought which is that, and forgive me, I can't remember his name, but the head of fisheries management in the Yurok tribe, he said, “The river is healing itself. Not we have healed the river, we are healing the river, the river is healing itself.” And that speaks back to where our conversation began, all those miles of current upstream of here, which is about life and agency of water: the river is healing itself.