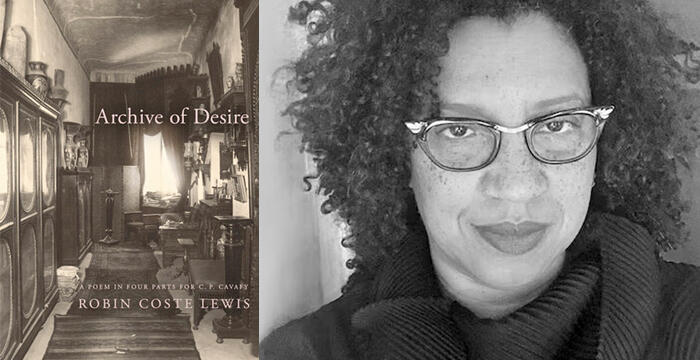

Robin Coste Lewis : Archive of Desire

Archive of Desire: A Poem in Four Parts for C.P. Cavafy began as a collaborative multidisciplinary project between the poet Robin Coste Lewis, the composer Vijay Iyer, the cellist Jeffrey Zeigler and the visual artist Julie Mehretu. This multimedia quartet traveled to Athens together to engage with the Cavafy archives as part of the composition of their performance, a performance now rendered anew on the page in Robin’s new poetry collection. We look at the different ways Robin alchemizes archival material across her three books, at questions of selfhood and desire when engaging with the poetry of another, at her unique relationship to time, at how queerness informs her poetics and that of Cavafy’s, and much more. A conversation that conjures everyone from Anne Carson to Lyn Hejinian, Daniel Mendelsohn to Ross Gay, and roams from ancient Greece to modern Alexandria.

If you enjoyed today’s conversation consider transforming yourself from a listener to a listener-supporter by joining the Between the Covers community. There are many potential rewards and benefits of doing so including the bonus audio archive which includes supplemental contributions by past guests, from Dionne Brand and Nikky Finney, to Ross Gay and Natalie Diaz. Learn how to subscribe to the bonus audio and about the other benefits to choose from at the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here if the BookShop for today’s conversation.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you by Ahmad Almallah's Wrong Winds. Almallah's third poetry collection considers the impossible task of being a Palestinian in the world today. Eileen Myles said about the book, "There aren’t marks to frame how I like or read or grasp at these poems. I found myself crying at a table in my lostness. Dear Ahmad, you hit all these places at once, disjunctive illumination." Anna Botkin calls Wrong Winds an epitome of poetic labor, a book that teaches the awesome responsibility of being fully human. Wrong Winds is available now from Fonograf Editions. The last couple of episodes, I’ve mentioned that we seem to be in the middle of an unanticipated trend where four of them this fall are about different strategies of engaging with the archive, diving into the wreck of it as part of one’s art making. I had mentioned the conversation with Olga Ravn about the Danish witch trials, and then Diana Arterian’s about the Roman Empress Agrippina the Younger, which would have made today’s the third of four. But I realized that really it begins a couple episodes back with Rickey Laurentiis, where we look at the opportunities and limitations of reaching back into antiquity for trans antecedents, which would make today’s conversation with Robin Coste Lewis about her new book Archive of Desire the fourth recent episode of five total that engage with history, erasure, reclamation, desire, time, imagination, and more. If you enjoyed today’s conversation, consider joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. Every supporter gets invited to join our collective brainstorm of how to shape the show going into the future, and every listener-supporter gets the resource-rich email with each episode, with the discoveries I made while preparing, the things we referenced during it, and places to explore once you’re done listening. There are a ton of other things to choose from, including the bonus audio archive, which includes an ever-growing treasure trove of contributions from past guests—from Ross Gay reading Jean Valentine, to Dionne Brand reading Christina Sharpe, from Nikky Finney reading from the diaries of Lorraine Hansberry, to Danez Smith creating writing prompts just for us. You can check this out and everything else at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today’s conversation with none other than Robin Coste Lewis.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I’m David Naimon, your host. Today’s guest, the poet and artist Robin Coste Lewis, received her B.A. from Hampshire College in Creative Writing and Comparative Literature, a Master of Theological Studies in Sanskrit and Comparative Religious Literature from the Divinity School at Harvard University, an MFA in Poetry at New York University, and a Ph.D. from the University of Southern California Creative Writing and Literature Program, where she was a Provost’s Fellow in Poetry and Visual Studies. But prior to all these academic achievements, she was a teenager from Los Angeles who left home for New York City, knocked on Audre Lorde’s office door in Hunter College, and said, “My name is Robin Lewis. I ran away from home. I read Zami, and I wanted to come to meet you.” Shortly after, Lewis secured an internship with Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the touchstone feminist publisher founded by, among others, Barbara Smith of the Combahee River Collective, and Audre Lorde herself. Her debut poetry collection, however, arrives more than a quarter of a century later on the other side of a traumatic brain injury that shifts her relationship not only to language but to selfhood. Her debut, Voyage of the Sable Venus, won the 2015 National Book Award in Poetry, the first time a poetry debut by an African American had ever won the prize in the National Book Foundation’s history, and the first time any debut had won since 1974. Past Between the Covers guest Claudia Rankine said of this book, “Voyage of the Sable Venus and Other Poems reframes the black figure, most specifically the black female, by pointing out the borders of black beauty, black happiness, and black resilience in our canonical visual culture. The title poem upends the language of representation, collected from the cataloging of the black body in Western art. Robin Coste Lewis takes back depictions of the black feminine and refuses to land or hold down that which has always been alive and loving and lovely. Altogether new, open, experimental and ground-breaking, Lewis privileges real life in all its complications, surprises and triumphs over the frames that have locked down the scale of black womanhood.” Voyage went on to be named a Best Poetry Collection of the Year by everyone from The New Yorker to The New York Times, The Paris Review to Time magazine. This year, the amazing French film director Alice Diop releases Fragments for Venus, a film inspired by and adapted from Robin’s book. Three years after Voyage, MoMA commissioned Lewis and Kevin Young to write poems to accompany Robert Rauschenberg’s drawings in the book 34 Illustrations of Dante’s Inferno. Lewis herself is also an artist who works in film, sculpture, performance, and textiles. She’s collaborated with everyone from Glenn Ligon to Lorna Simpson, and her work has appeared at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York and Paris and the 2024 Venice Biennale, among many other places. From 2017 to 2021, Robin served as the Poet Laureate of Los Angeles, and in 2022, she published her image-text collection of photography and poetry To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness, winner of the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work. Hilton Als described this book as “about how the dead do not stay dead.” Kevin Young called it “an achievement both cosmic and sonic.” Theaster Gates said, “Robin Coste Lewis has created a photographic and linguistic archive that draws from the pre-diasporic truth of family — family before Blackness and before the permutations of misunderstandings by others about ‘us.’ Her poems never stop offering me ways to more deeply understand the complex ways of being migratory, beautiful and optimistic in times of gross inequity. Lewis creates light and portals that reveal our truth through words and the images underneath our grandmother’s bed.” So it’s with great pleasure to welcome Robin Coste Lewis to Between the Covers today to discuss her latest collection, Archive of Desire, a poem in four parts for C.P. Cavafy, a book that originated as a musical, visual, and lyrical collaboration with the composer Vijay Iyer, cellist Jeffrey Zeigler, and visual artist Julie Mehretu, with Robin now bringing this multimedia performance to life once again on the page within her poems. Welcome to Between the Covers, Robin Coste Lewis.

Robin Coste Lewis: Thank you so much. I don’t know if I can even talk. I’m so moved by your introduction. I’m most especially moved about you talking about when I left home when I was 17 and what an extraordinary time it was. I mean, I don’t know where I got it in my head to really think that that was even a possibility. I was working in a department store in the lingerie department in Los Angeles, and I knew I wanted to be a writer since I was a child, and I remember just telling my parents, “I have to go. I have to go.” Because I would be turning 18 soon, they knew they couldn’t stop me, so they loved me in that decision. But I don’t know what I would do if someone showed up at my office door at my university because they read one of my books. I don’t know, you know. And Audre Lorde and Barbara Smith and all of the tremendous Cheryl Clarke, Jewelle Gomez, Cherríe Moraga, Shirley Steele, I mean all these amazing Alexis De Veaux, amazing Black women writers who—this was before the internet, you know—who used to make photocopies on, what were they called, mimeographs? Yeah. You know, just embraced me and welcomed me into this world. I was 17. So I was the person who made copies or set up for events, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that those were the kinds of readings that would be five people deep and four blocks long in New York City. You know, June Jordan, of course, Toni Cade Bambara, Sweet Honey in the Rock would often perform. And there I was, this teenager. [laughter] I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know how that happened. But listening to your introduction just moved me so deeply because most people don’t talk about that or know about that. I mean, Kitchen Table Press was a phenomenon in the literary world—a phenomenon—a press that focused on the works of women of color as a corrective to the feminist presses that were doing so much strong work. But we really had to fight. So in any case, I’m very moved by everything you just said. This is my first interview I’m doing for this book. I’m so happy it’s you, David. I’m so happy it’s you. I’m so happy it’s for this tremendous podcast.

DN: Thank you. I’m so happy you’re here, too.

RCL: Thank you. I’m honored.

DN: Well, before we talk specifically about your book, Archive of Desire, I wanted to spend a little time with some elements in your poetry that I think animate all three of your books and look at them under the umbrella of both the word archive and the word desire. Your three books all have an archival element, and even just what you just said, these citational gestures of love, I think, are archival. Voyage of Sable Venus foregrounds several millennia of art histories, representation of the Black figure, or put another way, an archival exploration of the pathology of the white imaginary when it comes to Blackness. In your second collection, one of the archives is the treasure trove of family photos under your grandmother's bed, documenting the everyday lives of your family who had moved from New Orleans to L.A. as part of the second great migration, where in a mere 30 years, the Black population of L.A. increased 1,000% from 63,000 to 763,000. One of the archives in your latest book is the archive of the poet C.P. Cavafy, which you were brought to in Athens as part of developing your collaborative interdisciplinary performance for the Cavafy-centric celebrations around the 160th birthday of Cavafy, celebrations that borrowed the title of your book as their title as well. When I think of the word archive, I might also think of the word history and the word memory and questions of both what we remember collectively and what is available to be remembered, and how what isn't there isn't there. That's something I want to explore with you later. But first, talk to us about a poetic practice that, regardless of how different these books are, is in conversation with an archive that runs alongside or dives into or resurfaces from or rearranges our collective historical memory as it forges a lyric.

RCL: Thank you for that question and for that close reading. There's a line in my book To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness where I say the body is the archive. Then the next line is “desire is our breastplate.” I think that's where I land most prominently—that we have been indoctrinated to practice intense disembodiment in Western culture. If you were colonized by any Western power, that includes you too. It began mostly with Martin Luther—I mean Martin Luther from hundreds of years ago—but also Descartes. You know, the idea that the mind and body are split is such a dangerous idea. Ergo reason, here we go. You know, there you go for another how many centuries. Then you add in all these different religious or philosophical ideas of the body, especially for me as a young girl. I was deeply religious, and I was the only one in my family who was deeply religious as a child and reading the Bible, and to see how they spoke about women's bodies—“as a place of filth and evil and of course in need of domination so that it can be tamed and brought into the fold of this patriarchal idea of family and all that.”

But I think—you know, I write about this in the epilogue of the new book—I think it also damaged men just as much. The notion of masculinity that we've inherited from so many traditions is so toxic. So I think that the process of decolonization is a process, mostly mental—Fanon said, right?—but it's a process of also understanding that the first archive is within you. Mostly through memory, sure. But I mean, memory like our cells have memory. Our DNA has memory. I've become a huge science geek because of the research I did for Realization. I mean, I read science for like 10 years. If I could go back and do a PhD in biology, I really would. It's just phenomenal when you think of everything our bodies are doing right now, just you and me here together, having a conversation in order to make that possible. So first and foremost—it's a long-ass way of saying—I think that we should never, ever forget that the grandest archive there is, is our own bodies. Most of the things that are the grandest, we can't even remember or know. You know, we still don't know what an atom is. Scientists get closer and closer to an atom, thinking, “Okay, we've nailed it down.” Then once you open it up and really look inside, there's more space in an atom than anything. There's just nothing but space. So all that said, I'm deeply intrigued by the body as a place of profound evolutionary mystery. I think that when I do go into repositories, archives, museums, libraries, my grandmother's suitcase—that I’m looking for the same expression. Like, here is life again. Here are cells that have been projected onto paper. Here’s a thought. Here’s a desire that’s been, however crazy, right?

I'm working on a project right now about torture within colonial slavery. Even that—even those archives—are fascinating to me because I see a mind that is sick, beyond sick, so sick I don't even know what to call it; who takes profound pleasure in tying another human being up and—forget whips, I'm talking iron hooks—and beating somebody to death for days on end. That archive intrigues me for the same reason. A, I want to know this history because we place too much emphasis when we think about slavery on cotton and sugar, and not about the torture, which was far more prevalent. I'd rather be in the fields than sleep on my master's floor any day. So those kinds of archives for me signal a body on the other end, and I'm interested in the body on the other end. Like the paper or whatever the archival object might be—it’s still a projection from the mind, and I think that's where I'm always trying to go: “What is this projection? What is this fantasy? What is this desire? Why do we even bother to document some of the things that we document as human beings?” That's fascinating. “Why don’t we document others?” I don't know if I'm answering your question, but you know that great quote—everybody talks about Derrida and Archive Fever. I remember once I gave a lecture when I was in graduate school about that the archives desire us. They have a fever because they want us. They need us. They're sick because they haven't been treated well, you know?

DN: I love that.

RCL: Whatever fever that's emanating from the archives, it's because they need our help and our attention. And I do deeply believe that too.

DN: Well, when thinking of the word archive, one can't help but also think about time, of reaching back to pull forward. But you have a distinctive relationship to time across your books that I think troubles chronology, linearity, and also identity. That feels devotional, perhaps mystical, but also like quantum physics. Just to scratch the surface of what you do with time, here are some examples from your books. From Archive of Desire, you say, “That town embroidered in bright white along the rim of a black crater formed 21,000 years ago, the only remnant besides the sea of a volcano that first began erupting, like me, three million years ago.” Or, “All the fallen and broken statues inside my heart.” And, “I am the 7,000 churches and the relentless marble, the elegant knots, the common rope, the ongoing reminders that we all began in caves.” In your second book, To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness, you say, “Lately, every morning, after a night of lucid insomnia, my first thought is always the same: fourteen billion years—our planet began fourteen billion years ago. I just lie there. Thinking. Then I move—slowly—forward, millennium by millennium, trying to see everything

that has taken place until I arrive at the present moment—me lying in my bed. Lately, I think about all of the other humans—now extinct—whose DNA spirals inside of our own DNA. Then I remember that we will one day—soon—be extinct, too. Fourteen billion years. I am terrified by the idea of my own death, but my cells scoff at the idea of four paltry centuries.” In Voyage of the Sable Venus, where you look at Western art from 38,000 BCE to the present, you say, "Here, one calendar takes eighteen years.

I am three. One day is an eyelash." And "I was pregnant. I was dead. I was a fetus. I was just born." Perhaps most notably and most powerfully, the scene in that book of a water buffalo who’s just given birth to a stillborn calf in the middle of the road, where you say, "She must turn around and see what has happened to her, or she will go mad." And I have to go back to that wet black thing dead in the road. I have to turn around. I must put my face in it." This feels like a fundamental element of your book—something you’re doing with time in relation to self and also to the collective—something that can be full of wonder and joy, but also, with this last scene, a suggestion that looking back can be fraught and perhaps dangerous to one’s sense of self, but is somehow also necessary to it at the same time. I wondered if this sparked any thoughts for you about this element that communicates across books.

RCL: Again, thank you so much for reading so closely. Those are some of the few things that I've written that I actually like—those excerpts that you read. I think, first and foremost, I went to divinity school because I'm interested in philosophy and theology and existential queries of “What is the universe? Where do we come from?” I've never been satisfied [laughs]—I can't believe I just said that—but I've never been satisfied with the answers we've been given, not even from science and definitely not from religion, although I like religion's ideas the best because myth embodies things that we only are now beginning to understand that they actually meant. We know now, if you study any Hindu or South Asian ancient texts, now scientists are just discovering that there was more than one Big Bang. Of course, yogis 6,000 years ago knew that just from watching the skies. There are just such great, gorgeous myths from all over the world that so elegantly represent a story about particular humans on a particular place on the planet at a particular time. You know, like in my book Realization, I'm playing with the myth of the flood, for example. As it turns out, if you really do deep research, there isn't a culture or place on the planet that doesn't have a mythological reference to the last flood. The one of which we are most aware is, of course, the flood in the Old Hebrew Bible. But if you really look, that story is told all around the world. That just fascinates me. We're so quick to go, “Okay, there was a flood.” Now scientists know, yes, yes, yes, there was a giant flood. Then we want to commodify it, fix it. But in actuality, there were many, many, many floods. The earth has burned and iced, burned and iced, burned and iced, and flooded many times. I just love that feeling when some kind of archival—usually geologists, right, or physicists in the archive of the universe—figure out it's so much more vast than we could ever, ever, ever, ever imagine. Like to think that at one time, during the Enlightenment of all times, they thought the earth was only 3,000 years old. God bless them. God bless them for trying. God bless them for trying. You know, a lot of people go to science because they want fixed answers. I go to science because I love the wonder and the exploration. So with regard to time, we still don't know what it is. We don't know. That’s sexy to me. That is so fucking sexy to me.

DN: I love that too.

RCL: There is this thing that we people talk about—a fish in water. That’s not what time is, right? I just love to think about how long human beings and other mammals, plants, all that. I guess what I’m obsessed with is the history of the cell. We all come from one ancestor cell. One. That’s insane, right? So for me, and I like to, as Toni Morrison would say, I like to luxuriate in the wonder of that fact. That is a fact. Several religions say things like “in the beginning there was light,” right? I think, yeah, because in that first cell, it was hit with some fire underneath primordial oceans. Then it all began. I just sit back and wonder about it all. But what has always been a problem is if you’re Black and female—or really if you’re anyone—you’re told, "No, no, no, no, no, no, no. You were a monkey. You were a savage. Thank God we took you from that heathen continent, Africa, and brought you here and gave you the good Lord Jesus Christ and this Bible and tortured and beat and killed almost 80 million people into submission so that you could then know that you and your history is no more than 400 years old. It began in America." How fucking dare you? How dare you? So there’s a part of my obsession with time that is also about—you know, there are lots of calendars in the world, people. We keep in America—which I just think is part of our problem—we keep believing that our story is only 400 years old. I mean, Europeans at least get to be told that they came from—they had other things going on in Europe, right? But for us, it’s just like, no, the only thing you had going on in Africa was savagery. “You were monkeys. We saved you. You were heathens. You have three-fifths of the brain. Bend over. You’re nothing.” So I think there’s also a part of me that uses my obsession with the history and evolution of time as a way to protect myself from the ignorance of American ideology around its inception. It’s ridiculously limited. It’s also very, very clever because if you tell me I was nothing but a monkey before 1619, and if you represent that as truth, whereas I’m also, Julie Mehretu, the painter, and I have worked together on a lot of things, and we’re also dear friends, and one of our obsessions is architecture, right? So we’re constantly sending each other things on the continent. Like, I didn’t know about Lalibela, one of the most beautiful churches on the planet that was hand-carved in Ethiopia thousands of years ago. Right now in Senegal, which is where a lot of people came from to Louisiana, they’re doing digs on shards—pottery that’s 3,000 years old. Where is that history being taught to Americans? It’s not going to be. It’s not going to be. What’s even more terrifying to me is sometimes we do it to ourselves. I’m talking about Black historians, Black scholars, myself, right? We think, “Oh, America, America.” I’m just like, America is just a manufactured nation like all the others. Doesn’t mean it’s not real or doesn’t mean it isn’t something that we need to take seriously—that fantasy of a nation—because the fantasy is an incredibly savage nightmare from which we have to help each other wake up. But that said, I’m not going to live in that nightmare 24/7. So the way that I play with time helps me to expand the universe for myself and hopefully my reader as a kind of reminder that the universe—you could never begin to understand it. I’ll say this one more time. I’ve said it before. There’s a cave in South Africa called the Blombos Cave that I’m working on. They found art pieces 70,000 years old. Seventy thousand. Now, for those of your listeners or for you or whomever, we were told that the reason why Western art history was the central tenet of what art is, is because of the cave paintings in Lascaux and other places, right? So now, paleontologists, archaeologists—we’ve found this cave that predates all the other caves on the planet by at least 30,000 years. But the cave was also continually inhabited for 150,000 years with all these beautiful artifacts, right? People don’t even talk about it. They know about it. They have to mention it. You know, there was a book on Ice Age art, and they’ll be like, “Yes, we know about the Blombos Cave.” But can you imagine if that cave was found in, like, I don’t know, Germany or Spain or any of the other places where they found caves? The kind of rush we would have all made from so many different disciplines to really understand what does it mean that 70,000 years ago, someone carved some chevrons on some limestone and not in any other place but South Africa. So I use all of this to hold myself in a place of aesthetic sanity, I hope, when it comes to thinking about history. Also, as a shield to refuse the tragically reduced notions of time that I think we use to imprison our bodies. As I say in one of my books—you quoted it—“Four paltry centuries, that’s all you got? Four paltry centuries doesn’t do shit for me.” It shouldn’t do shit for anybody else. It’s a century. That’s not a long time.

DN: No. Well, as a first possibly oblique step to talking about desire, the other half of your title, I’m going to hand over the next question to the poet, writer, and translator, Diana Arterian.

RCL: Fantastic. I’m a big fan.

DN: Diana, who is to thank for bringing you and I together today. Diana, who was just on the show to talk about her book Agrippina the Younger, with its own mode and means of diving into the wreck of the archive, of history, and of collective memory. Emily Van Duyne says in the Los Angeles Review of Books about it, “Arterian is a fine storyteller, moving the reader deftly between Agrippina’s real and imagined histories and the poet’s present-day search for her. The book is cleverly paced, arranged so that Arterian’s quests seem to reveal Agrippina’s secrets. Before long, I felt infected with the loving obsession that drove the writing of this book. History and the dead demand our time, rage, ambition, and attention, and this is ultimately the voice that Agrippina the Younger amplifies with fury and grace.” So here’s a question for you from Diana.

Diana Arterian: Hi, it’s Diana Arterian. David, I’m so deeply honored to be among Robin’s likely illustrious cadre of people you invited to ask questions about her stunning new book. Robin, I just hope you are reveling in what seems to me the obvious ways this collection is locating an expansiveness that feels new but continues to turn toward your most pulsing internal questions. So there are many animating themes in your work, and I hesitate to circumscribe you at all with a question. But desire, devotion, faith, and beauty certainly, which all live alongside, impossibly, the darkness of humanity. But my question is about embodiment and probably a kind of amalgamation of these themes. I think of how some of the most ancient human materials we have found are adornment. The minute we were even a little comfortable, we were making beads to thread into our hair. There is the ancient obsidian stone shined until it was a mirror from 8,000 years ago. We have been deeply interested in our bodily beauty forever. In the Sanskrit love lyric from the 11th century, Chaurapanchasika by Bilhana, one piece states, “At this moment of my death, nay, even in my next birth, I shall ever remember that swan in the cluster of lotuses of iove, with her eyes closed in the ecstasy of love, all her limbs relaxed, while her garments and the tresses of her hair were strewn in disorder.” Beauty transcends lifetimes. Then we have Cavafy, who you have engaged with so powerfully and in your amazing epilogue illustrate to be a touchstone for queer people in the 80s and 90s here in the United States, despite his being a writer from across the world in another language from half a century prior. Your kinship seems obvious, particularly when he links the body with beauty. In his poem “So Much I Gazed,” he says, “So much I gazed on beauty, that my vision is alive with it. Contours of the body. Red lips. Voluptuous limbs. Hair as if taken from greek statues; always beautiful, even when uncombed, and it falls a little over the white temples,” which reminds me a lot of Bilhana’s words from the 11th century. In your first book, in your poem “On the Road to Sri Bhuvaneshwari,” which I truly consider a masterpiece of American literature, you describe the Hindu goddess Parvati’s body broken into pieces, your own body through injury feeling like it was broken into pieces, and the ways in which the crushing history of white violence can break any spirit to pieces. Archive of Desire attends to the body, yours and others, in ways that largely seem defined by wonder. At one point, you write, “The image of my young body closed and perfumed,” and go on to say, “I contained a beauty even God was unable to put away.” I’m curious if this sense of memory, beauty, and embodiment is something you have traced in your work, and if you know its origins? Is it your work in Sanskrit, your experiences through your injury? Was it there when you were a child? I cannot wait to hear your thoughts and congratulations.

RCL: Wow. Diana and I were in a workshop once at a USC PhD program, and we became fans of each other’s work, but more of each other’s minds. This woman is so smart. I remember the first time—I’m holding up her book, which is right here—Agrippina the Younger, which is just extraordinary. I can’t wait to hear the podcast you guys did, David. I remember the first poem she began writing for this book when we were in those workshops. I was like, “Who is this woman?” Because of all the—I mean, you just heard that question—but also because I thought I found a comrade, an aesthetic comrade with regard to a person that could hold a lot of time in her mind while working and hold it elegantly and lyrically. So her question was about adornment, beauty, embodiment. I mean, my first hit is I’m going to say Blackness. It’s from Blackness. It’s from my childhood. I grew up in a culture, right? Gulf culture. That I’m only beginning to understand. My first book, Voyage, is coming out in French, on Gallimard, in a couple of months. I had to write an essay for it. I ended up writing this long essay, accidentally, about the history of free people of color in Louisiana. That history is from where I am descended, from which I am descended. I don't know how to explain the profound, ferocious insistence upon dignity and beauty in which I was raised. I mean, I know it now because I'm middle-aged. I know that it was not normal for everyone to have a grandmother, however poor, to starch, whisk, make the starch, whisk the starch, make the dress, get the material, make the dress, then wash it, whisk the starch, make the starch with lovely collars, for you just to go to school in a school that's like, who's just like me, built with poor people because she wanted me to be adorned and she wanted all of us to be adorned. And at the time, it just felt like, "Oh, get the scratchy collar off of me, Grandmother. Why do I have to dress like this, think like this, whatever?" But now that I am older, and when you consider, like, the lynching rates at that time, the KKK was coming down our streets. The KKK was marching, fully hooded for—I mean, marching, campaigning, fully headed in the office, right? Just the outright violence by the state. The LAPD constantly in our neighborhood, shooting constantly. I mean, we grew up in a war zone. Eighty percent of the boys I grew up with are dead. Dead. So when you put a frame around this, then you realize how political it is to put a necklace on a little girl. It changes something for you. Then not to mention, I mean, they just had style for days, for days, for days, for days, for days. I mean, God, and my grandmother and her sisters, they were all incredible. We call them seamstresses, but they were tailors because they had that much skill. They can make anything—anything, anything you wanted—just by eye. You know, “You like that suit? Come over tomorrow. Be ready.” I mean, this is the attentiveness, right? She could look at you and tell you the width of your chest, the length of your arms in inches and millimeters. Then there was all the emphasis on the beauty of the natural world. My grandmother was an incredible gardener, and she had a greenhouse. When I tell people my grandmother had a greenhouse, they think we grew up really rich, but we didn’t. She had one of my aunt’s boyfriends build it for her. In that greenhouse, she grew orchids and anthuriums and dahlias. I was with her all the time. It’s not just that kind of beauty. It’s like, can you sew a straight line for a seam? It’s really difficult. To watch the meticulousness with which these people not only made things, but the meticulousness with which they loved each other, and the really elegant performance of manners. I feel it all the time when I’m writing. Like, don’t be lazy. Don’t be lazy with this line. Don’t be lazy with this word. Look at the thesaurus. See if it’s actually the exact, exact, exact word you want. Yeah. So I think that is the origin. Richard Pryor is a really huge influence in my life. He’s such a beautiful theorist and has so much existential thought in his comedy. There’s just that sense of wonder. I grew up with that. I grew up with that.

DN: Well, to extend the seam of this question of Diana’s, this question of body, memory, and desire, we have another for you from the poet Aracelis Girmay. Girmay’s latest book, Green of All Heads, arrived, like your book, this fall, and M. NourbeSe Philip says of it, “…is liturgy, is prayer, is GREEN OF ALL HEADS, for the living and for the dead; for the quotidian and for the extraordinary. Precipitated by the unexpected transition of her father to the realm of the Ancestors, the poet Aracelis Girmay decodes the Great Code that is poetry to bring to the ‘smallest bone of (our) ear’ the single memory that is love, fecund in its singularity. Alongside the poet we pace the rhythms of grief as well as the everyday to approach the revelation that while death never rhymes with life, it provides us the extended bassline riff supporting our livity —those bright, bold notes echoing the sound we were and are and will be running out of this life. …is benediction, is prayer, is eulogy, is chant; is mourning ground, is grief, genealogies of; is life, is is & am, is altar, is GREEN OF ALL HEADS, filmy netsela of blessings gently landing on our heads to embrace, to hold our fragile mortality, ever luminous in the ordinary.” So here’s the question for you from Aracelis.

Aracelis Girmay: Hi, Robin. This is Aracelis. Thank you, David, for having me. I feel like I’m realizing a long-held dream to call into the radio station to dedicate a song to a loved one. Robin, I am sending you my love, and it’s just a real joy to thank you for your exquisite work in this way, to thank you for your long sound, read after read, never the same, like a shape coming into view from or in the horizon. One of the things that really stuns me about this new book, but really all of your work, has to do with the erotic and scale. It seems to me that you are ever aware of and working with a vastness of scale, millennia, that does not diminish but rather energizes the intimacies and details of particular and particulate bodies, even single touches, imbuing them with a kind of cosmically scaled, somehow geologic sensuousness and force and eroticism. In your poem Handkerchief, “The wind moves against the ocean with liquid symmetry.” You write of a crater as, “The only remnant besides the sea of a volcano that first began erupting like me three million years ago.” Somehow this all holds hands with or feels related to a moment in the same poem when the speaker addresses Cavafy and says, “The silver in the paper shines out from your bedpost. How did you fit them, plus all the twelve gods, and your desire too, into such a small bed?” I could go on quoting you because I find it quite fascinating to think about. Robin, I would love to hear how you think of Eros and time, and some of what that vastness of scale makes possible for the erotic.

RCL: I can never come on the show again. [laughter]

DN: Why not?

RCL: I’m just so overwhelmed by the incredibly dark, strong, rigorous beauty. You know, just so overwhelmed. You guys, I’m older than both of them. Diana and I just figured out she’s as young as my niece. But I consider both Diana Arterian and Aracelis Girmay to be elders in line aesthetically. I apprenticed myself to their work to try to learn how to become a better poet. Also, I’ve just had deep and profound aesthetic moments about what poetry can do by reading them—in this case, reading Aracelis. So thank you so much, David. Ara, I wish I could just be with you right now. Okay. So you can’t overwhelm people and then expect them to be in any way coherent. [laughter] Eros. So I speak about this, I think, in the epilogue of my new book, how in most cultures desire is a god, mostly a goddess, as such honored, adorned, worshipped. And it’s a very different way to think about desire from the ways in which we were indoctrinated by different frames—all those religions I just spoke about earlier. But if you go to other places where desire is not evil and bad, then you’re in a kind of existential playground. Like, what do you do with yourself? You’re suddenly unhinged into the kind of universe. I’m interested in desire as a phenomenon, especially, as I said, in terms of evolution, down to the cell, because when you really, really think about it, nothing could happen unless desire took place first. So in my obsession with evolution, I’ll just give you a quick example. Cells, before they evolved or developed eyes or eyesight, they couldn’t see. You know, you have all these bacteria roaming around the primordial earth, and they can’t see, and everybody’s eating each other, and you can’t tell what’s going on, what’s going to happen. So they know that there was a desire of sight by certain organisms. But you would think the eyeball would evolve first, but that’s not what evolved first. What evolved first was the dent in their body to hold the eyeball once it evolved, even if that were twenty generations forward. That’s just incredible to me, right? I think queerness and Blackness too, right? We were told so many of our desires were evil, they were wrong. I mean, now, you know, thanks to so many of us who are out there marching for decades and writing letters and presses and all that. Now it doesn’t seem—I mean, it’s still horrific. I mean, look what’s happening in the country right now. But I think there’s a certain psychological strength that comes from being born in a body that you’re told is poison and savage. Yet you fall in love, say. Love is the biggest kind of correction of all to everything. You know, I talk about this in the epilogue. Rita Dove says when you experience love, the experience is massive, inconvenient, and undeniable. And so there’s no way, there’s no way, there’s just no possible way, especially when I was a teenager, both as a Black girl being called a nigger or having a gun put to my head by the LAPD, there’s no way in the fucking world that I was going to sit there and go, “You know what? Yeah, well, yeah, because I’m a savage. I’m just a little old darky. So yeah, I need to be policed,” right? So Blackness is such a gift to me in terms of Eros because you desire other things. If you can, with the help of your community, reading, music, art, adornment, Diana—if you can—you can walk straight through all of that because Eros, Eros is your guide. Eros is your guide. It’s like, no, but I want this. I want this. “Want” becomes a holy thing, a holy, sacred, the most powerful thing of all. Anne Carson has that great book Eros, which I just love. It becomes one of the greatest powers. You know why? It is. Because cells desire to see. That same impulse—we’re made of cells—is inherited in everything we do. So I met a girl in college, and I desired to be her love. That would send me on—we fall in love. Or we desire, like you, to have a podcast. Where did that come from? “Like, it’s so easy to—no, but I’m serious—it’s so easy not to take our minds seriously.” It’s so easy not to take these ideas and dreams seriously. But that is where it’s coming from. It’s coming from these impulses. It’s coming from Eros. Eros is vast. It’s just not about, “Oh, I want to hook up with somebody.”

DN: Let me tell you what Aracelis’ question brought up in me, and tell me what you think about it too.

RCL: Sure.

DN: Because when thinking about the erotic and scale and the erotic in time, I think of an anecdote that you’ve shared, I think long ago in an interview, about Audre Lorde being really late for a meeting. [laughter] She’s like an hour or an hour and a half late.

RCL: Totally, she was always late.

DN: You're like outside of the building. So being late, being an hour late, an hour and a half late, there's a time pressure, expectations by other people. There's a set linearity in chronology. Instead of going in, she stops, she checks in on you, slowly peels an orange, and feeds you wedge by wedge into your mouth. [laughter] I'm thinking maybe the erotic has its own weather or its own ability to create its own time.

RCL: Yes.

DN: Its own scale, even within another time.

RCL: Yes, yes, yes, a thousand percent. I'm so happy you brought this up. Maybe the erotic is its own country, its own place, its own nation that exists simultaneously side by side with us at all times and that we can immigrate to it. You know, at any moment, we can just step over in our minds and be in this other country, you know. I think I know what I'm trying to do in some of those lines that you mentioned, and Aracelis mentioned, is I'm trying to decolonize English to make it a nation of the erotic. By the erotic, I mean a nation of blackness. Like I'm trying to take English and really turn it around and make it work, even though it's a language of intense colonization worldwide. I'm trying to make it into the blackest, darkest, sexiest, most beautiful, adorned, mysterious language possible because it's all I have, right? I can do that through Eros.

DN: That's wonderful.

RCL: All I have to do, all I have to do is be brave enough to say, when I hear these thoughts, “Okay, I'll write that.” That's the difficult part. It's not so difficult for me anymore. I rather enjoy it now when my psyche wants to write something that's utterly crazy. I'm like, "Yes, thank you. Take me out of this fixed place and into this other place."

DN: Well, thinking of the body as an archive, in a conversation with Jesse Nathan, the poet Richie Hofmann said this about Cavafy, “I love in his work the sense that, even in the moment of encounter, it is all being stored away, preserved, its fragments filled in as by a conservator. The sensuousness must be saved against the fear of loss, of vanishing entirely, the erotic always intermingling with elegy. Later in that century, Louise Glück’s poem asked and answered: 'Why love what you will lose? / There is nothing else to love.'” Before I ask you more about the body, desire, and time, in the aura of Diana and Aracelis, I was hoping you'd read for us the Cavafy poem, Body, Remember.

RCL: No, I'd love to. The resplendent poet Lorca was executed at point-blank range, mostly primarily for being queer, but also because he was so damn smart, which I'm beginning to think are the same thing. He was executed 20 years after Cavafy died, and Cavafy was very aware of the possibilities of being targeted by his own country for the crime of desire. By that, I mean homosexual desire. I think it's really important to remember when we speak about Cavafy and his silence that some of it might have been—I mean, it's there in the archive, where he's leaving notes for whoever is going to take care of his archive later—“This poem, destroy it completely. This poem can remain, but don't publish it until I'm gone.” So we would be remiss not to talk about that very real terror that so many queers of this time were living under. I don't know if there was a country at the time that wouldn't stone a queer person to death, if not worse. I just wanted to say that because what's remarkable to me about Cavafy is that, like the people you just quoted, right? He still managed, however, anyway, despite the guns at his head that weren't there but would be there, if they knew just how active he was sexually in the streets of Alexandria at night—cruising men, having fun. I mean, his poetry and his life is so rich, especially later in the years with his beautiful escapades with Egyptian men at night. He also paints this really gorgeous scene of queer culture for men in Alexandria, especially in the cafes—how you could pick up a man or be picked up by a man. I want to make sure we remember that some of his silences and slippages in his poems could be about that. I wonder if he could write now what he would do and say if he weren't worried. Because a lot of his friends were disappeared or killed. This is Body, Remember by Constantine Cavafy.

[Robin Coste Lewis reads Body, Remember by Constantine Cavafy]

DN: There's so much in this short poem that feels to me deeply connected to your poetic cosmology. That a big part of the body remembering is relational, where one sees desire in another and where the borders of individual identity get transgressed. Because it's unclear where one person's desire and your own begins and ends—how one finds one's own desire in eyes that looked at you. I think of—this might be a stretch—but I think of Solmaz Sharif the last time she was on the show, talking about how she hates empathy because its uses are self-preservation. She says, “What it is, is like, I will experience you for a moment in a way that I can enter and exit and still go grocery shopping undisturbed.” [laughter] She says empathy “allows for the absolute and unhindered continuance of what is. I'm very much against that. I'm very much for ending that. I think the only way to that is actually love.” Elsewhere, she says, in contrast to empathy, where you can step into a life like a therapist who can open and close a door, love is none of these things. Love can get you fired. “If you replace the word empathy with love, it will reveal the lie.” This makes me think of what you just quoted earlier of Rita Dove, when she says that love is massive, inconvenient, and undeniable. I also think of W.H. Auden's introduction to Cavafy's poetry, where after making the dubious assertion to me that what distinguishes poetry from prose is that prose can be translated and poetry is untranslatable, he confesses to being nevertheless perplexed and disturbed by how deep Cavafy's influence is on him, despite not knowing himself a word of modern Greek—that this influence comes to Auden via other languages Cavafy didn't write in. Perhaps I'd argue that perhaps it's love that brings this through—the love of those translators and Auden's own love for Cavafy. Similarly, it feels like it is through this transgressive boundary-crossing aspect of love that you collapse time and space. When you say things in the book like, “I want to be like that town built at the top of an island, fortified by ancient sight, the humble houses huddling warmly together, doors caressing the endless black rock.” Right from the opening words of the first poem in this book, a 27-page poem called Handkerchief, we are in encounter, in relation, where you're observing an old street seller selling roasted nuts. You say that it is only a matter of days when you too will “stand somewhere, hoping another human will stop and find what I'm offering interesting.” We're introduced to Cavafy in this book here, not as a single figure, but as a person in correspondence, in this case with Virginia Woolf's husband. So I don't know if this sparks any thoughts, but as a preface to maybe reading the first four of Handkerchief, maybe you can preface it with some thoughts and then we can just hear an excerpt of the opening poem.

RCL: I love that you think you could come at me with all these brilliant ideas and quotes and think I could put together anything even remarkably coherent. [laughter] I'm sitting here just stunned. I want to go back to a few. So the quote by Rita Dove, that love is massive, inconvenient, undeniable—it's from a poem of hers called The Regency Fete, which is one of my favorite poems of hers. I just want to say for the listeners, the next stanza after she says all this, and then there's some other work that she does before she comes back to this idea that love is massive, inconvenient, and undeniable, she nevertheless then ends the next stanza with, this is a poem that's set in 1811, so just so you know that's what the language is, it's a persona poem, she says, “If love were to draw its sword, I would kneel and bear my neck.”

DN: Wow.

RCL: That's what comes after, right? It's in parallel with the stanza before it. I think it's really important to keep those two lines together, even though they're separated by a stanza, and other work, because she's not saying in this poem, “Yeah, it's massive, inconvenient, and undeniable.” Yet, aren't you lucky? Aren't you lucky? The only proper response is to bend over and let it take your head, right? When we were talking about Diana and beauty, I wanted to say the other place I resourced my beauty besides having grown up with some extraordinarily elegant people who thought about elegance as a political tool, I was so happy to hear Diana read a poem that was translated in Sanskrit. The Sanskrit myth—talk about adorn—the language itself is a language of adornment, and not in a sappy way, right? In a way that takes your head off. To see all of the incredible poetic play happening in Sanskrit poetry, especially in the myths, in the epics, but also in other places, it's just remarkable. So I learned a lot about shape-shifting, you know? I mean, that's one of the places I get time from. I mean, in Sanskrit cosmology, we're 15,000 years into the Kali Yuga, which is going to last 25,000 years. It's the worst age of all, but it's also the return of the feminine. But before that, the last age was 50,000. Well, I swear to that, there were several hundred 50,000 years. I mean, it goes on and on and on and on and on. There's a moment in one myth where Rudra, the great, great god—he's one of the greatest gods in the Hindu pantheon—he's feeling himself, and he goes up to a bunch of gods. He's like, “Hey, hey, I'm back” from his reincarnation. I forget which god it is. It's probably Shiva. I can't remember. There just happened to be ant season. So there were some ants crawling along the temple floor. Whichever head god it was says to Rudra, “You see those ants?” Oh, I'm sorry. Rudra has lived for millions of years, just so to be clear, speaking of expansive time. Anyway, whichever god it was that was dominant then over Rudra said, “You see those ants?” Rudra's like, "Yeah." He goes, "Rudras, all of them," because of course, in the Hindu pantheon, transmigration, reincarnation is real. Nothing could be more real. So telling him, dude, this is just one reincarnation. You have so many more to go as Rudra, right? That notion of time and bodies has also helped me think about the beauty of intimacy and letting go and coming back together. In India, it's nothing to say, “If not in this lifetime, then another. I'll see you next lifetime. Didn’t work out here, but it might work out there or you better not find me.” [laughter] So anyway, okay, I digress. Yeah, there's so much in what you're asking. Then will you tell me one more time what you just asked? I just wanted to backpedal to those things. What did you just ask me?

DN: This fundamental relationality in your work, like in Body, Remember, maybe you even see your own desire in the eyes of another.

RCL: What I see in my own desire is a searing hot honesty that we have not been taught to acknowledge nor hone. Yet, it's probably the most powerful impulse that we embody. It feels like a profound gift. I'm not talking about silly desires. I'm talking about real hot desires that stop you in your tracks or keep you up at night or whisper to you to learn how to take that seriously, especially as a woman, you know, to take your mind seriously. Diana's book Agrippina, what a profound gift she's given us in taking this woman who was villainized in the ancient world and dealing with the complexity of her biography. When I first started writing, I used to cry a lot because when I would pick up a pencil, I would remember the laws in America about prohibitive literacy for Black people, that Black people were not allowed to read or write. There are horrible stories about enslaved people or even freed people having their hands cut off, tongues cut out, eyeballs gouged because they learned how to read the word “the.” So whenever I would hold a pencil, I would just stare at my hand and cry like, “I really want to write.” Yet there's this horrible history. That took years to adjust and to triumph over. I don't think I was feeling held back by the indoctrination. I think I was feeling held back by the grief to think of all of those people all over the world, not just enslaved people in the States, not just Africans, but all over the world who have been like Cavafy, repressed. Then we take it one further and repress ourselves. So Eros has a way, Eros has this searing hot sword that says, “No, no, no. None of that. None of this is important. We're going to do this anyway.” One of the things I just loved about Cavafy's archive is having said everything we've said, I mean, as dangerous as it was, you have queers throughout time—throughout time, speaking of millennia—throughout time still, still finding each other, celebrating each other's desire through sex, through friendship, through community, through publications, through art. You know, then you go to Greece where homosexuality doesn't have that same shame, or Persia, right? The ghazal, which is one of my favorite, favorite poetic forms—the ghazal, which was birthed in Persia—came out of a longer form, but the ghazal was made so that men in court could sing couplets celebrating their love and desire for the younger men at court.

DN: Wow. I had no idea.

RCL: Right. Neither did I. So all of this is in my head, and all of this is in this book. It became a true interrogation of what queerness and desire is. What is the relationship with those two remarkable phenomena with language, which is probably the most—speaking of remarkable human phenomena—those three things. Lyric too, the song.

DN: Well, let's hear the opening four pages of the opening poem, “Handkerchief.”

RCL: Yeah. I just want to say for your readers, when we were in Athens in Cavafy's archive at the Onassis Foundation, we witnessed Cavafy's sartorial dandiness. You know, he loved nice shirts, he and his brother, and he loved handkerchiefs.

[Robin Coste Lewis reads a poem called Handkerchief]

DN: We've been listening to Robin Coste Lewis read from Archive of Desire. So one of Cavafy's translators, Daniel Mendelsohn, is a past guest of the show. While Cavafy wasn't the focus of our conversation, I did glean some of his thoughts on Cavafy to use as part of posing questions to him. I wanted to bring some of Mendelsohn's thoughts on Cavafy into this space just to see what it prompts in you—whether it's something harmonious, oblique, in opposition. I'd be curious to hear what Cavafy means to you in the light of what he means for Mendelsohn. In one talk he gave on Cavafy, he begins at Cavafy's deathbed. He's dying of laryngeal cancer, and he can't speak. Instead, he draws a circle with a dot in the center as his last communication, and then he dies. Improbably, he dies on his birthday as well, completing a circle like the one he just drew. Mendelsohn's lecture arises from this image, talking about the three ways Cavafy tries to reconcile the periphery and the center—the circumference and the axis—those being the spatial, the temporal, and the erotic, or the geographic, the historic, and the intimate. Geographically, Alexandria, Egypt, his home, was once central and is now a forgotten place. Historically, Cavafy focused on a span of time and antiquity that most people studying ancient Greece would overlook. Instead of focusing on Athens and Rome, he focused on Antioch and Libya and other places that may have once been centers but aren't anymore. Temporally, he's interested in late antiquity and Byzantium, which most people skim over. Finally, with the erotic, Mendelsohn speaks to Cavafy's homosexuality. Mendelsohn argues that what makes him a great poet was him figuring out how to relate the spatial, temporal, and erotic in a concentric way. I might add that it is also perhaps in the ways he models how people on the margins or on the periphery are their own worlds with their own axes. On social media, you recently posted a bell hooks quote: “Queer not as being about who you're having sex with, but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and that has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.” It feels like Mendelsohn is suggesting that Cavafy is queer, perhaps in three different ways, three ways that he's able to ultimately harmonize. I wondered how any of this strikes you around the meaningfulness of Cavafy for you.

RCL: Thank you. Thank you so much. One of the many, many, many things about this project that I talk about more in the epilogue is that for many, many, many queer people for the last century, Cavafy has been a whole country unto himself. If you're lucky enough to find his work, then you can be saved by it because he's not only in some of his poems exalting queer desire, even with all that slippage that we just talked about, he's also redefining those temporal historic time periods you just mentioned. It would have been so easy for him to write about whatever—something more recognizable in Homer, say, right? But he found other men and other narratives in which to enter and to use and to also offer a corrective. I want to talk about that circle within the dot. I saw that note, and I saw other notes that he drew on his deathbed when we were in his archive. That was especially exactly what Mendelsohn said. It was so moving, knowing that he could no longer write nor talk. I think, and it's quite possible and probable that I'm retrojecting onto him, but I think we all—Julie Mehretu, Vijay Iyer, Jeffrey Zeigler—when we went to be in his archive, I think we all walked into that archive as diasporic people and from very different diasporas to pay our homage to another diasporic person. The Greek diaspora is just fascinating, and it wasn't until I really started research on Cavafy's life and then how to research the Greek diaspora in Egypt—the Greek diaspora, I'm talking about mostly 19th century, early 20th—in the UK, his family's moving all around, Constantinople, all of these things, and just wondering, wondering for myself, “You know, Cavafy never lived in Greece.” All the ways that he, like the rest of us, grappled at times and engaged this grand history. I mean, a history because it's so exalted in the West, it would have been really easy to get lost in. But he never does. He never does. So I feel, and I don't know if I would be speaking too much on others' behalf, Julie, Jeff, and Vijay's. I write about this also in the epilogue. I feel like we all recognize the kind of dateless bliss that comes from not belonging to any nation, regardless of the ways in which nation believes it belongs to you. And how that kind of, at the very least, intellectual statelessness, but aesthetic statelessness, allows you to do things in your work that, had you not taken that step over to the nation of the erotic, you'd still be stuck debating with a tyrant about whether or not you deserve to breathe air. That's just not a worthy conversation. So Cavafy, that was a homecoming. I talk about this also in the epilogue, how when I was growing up, Cavafy was the person—I don't even know how we found—I know how I found him, but let me put it this way. I have yet to meet anyone, stranger or friend, who asked me what I'm working on. I say, when I was working on this book, a book about Cavafy, who is the matter of reverence. These are people of color, people from all over the world. The letters I got were people saying, I almost killed myself in two of it. Because my family had disowned me. I was on the streets. Then someone gave me a Cavafy poem. So I don't want to downplay that also. You know, the strength of his poetry, the ways in which that space that you mentioned allowed generations of people to walk into his poems and remain safe from their own kind of personal and historical terror. It's pretty profound.

DN: Well, to stay with why Cavafy for yet another moment, and with your previous work of diving into the wreck of archive on behalf of the Black diaspora—something that I think we can say you're also doing in this book too—but here you're also writing across difference in this really tender way. It’s toward a white poet of great renown who engages with classical antiquity. Part of what you catalog in Voyage of the Sable Venus is the ubiquity of the perversity of the subjugation of the Black figure throughout art history. Black figures as knife handles or mirror handles or tables where each leg is a Black woman whose hands extend above their heads as if holding the table up. Classical antiquity, whether Greek or Roman, was not remotely immune in this regard. As one random example, wine cups that revelers drank from in 5th-century BC Athens of Black people being eaten by crocodiles. The impulse to create an alternate archive liberated from this is one that you engage with in all of your books in different ways. But your reaching across to Cavafy reminded me, at least obliquely, of Tracy K. Smith deciding to translate the poetry of the Chinese poet Yi Lei, because she felt that reaching across difference was what was needed in the world. She has written about translating Yi Lei's poem Black Hair: “Working on the poem, I saw clearly how the recurring image of black hair signifies within the specific context of Asian femininity, and yet in my hands—in my mouth—the phrase “black hair” began to make space for a second set of values and vulnerabilities as informed by my racially specific experience.” She then explains how she lets her own voice harmonize with Yi Lei's within the translation rather than trying to erase her voice, and says, “This is the miracle of translation, to me. I am elated that a Black woman in the US, alive in the midst of a national racial reckoning, might find her reality bolstered and clarified by a Chinese woman’s poem written on the eve of political uprising. What might it mean for a reader to be assured that her self as marked by race or any other signifier of identity need not submit to being an effaced presence in another poet’s lines, need not be a silent witness or mute interloper? What might it mean for a reader to be urged into vocal participation? What might it mean to be told all are welcome here?” When I read this, I think of one of the poems in the book, Cavafy in Compton. I wondered if you had any [laughter]—I would love to hear any thoughts you have about this and any introduction you want to give to us about this poem. And then let's hear Cavafy in Compton.

RCL: Okay, I'm going to get to that in about 20,000 minutes because you just gave me another mouthful. I want to say that that poem that I keep quoting from of Rita Dove's, The Regency Fete, that I keep saying is in 1811, this is a man who is responsible for, and his entire monarchy at that time, responsible for the murder and death and slaughter of millions of people in South Asia with the East Indian Company, in the Caribbean with the West Indian Company. I mean, this is at, like, one of the worst parts in the history of the genocide of Africans via slavery. Yet she decides to write a poem, a persona poem, in his voice, right? He's giving a huge party and she uses this man to write this poem. It's a kind of manifesto for beauty and love, and like, no matter what, don't you ever give up on love and beauty. It's such a kind of—I don't want to say a reverse colonization because I don't think Dove would be interested in that silliness, right? I don't think she's interested in tit for tat. But it's just such a powerful—so this Black woman from the 20th century embodies the body and voice of a person in the monarchy who is responsible for the enslavement of all these people of which we are their descendants. Yet she makes it a manifesto of profound, powerful beauty. I think in listening to you talk about Tracy's translation, there's so much going on in this, right? In Voyage, I had to do the same thing with all of these titles. I mean, they were just awful, heinous, yuck, disgusting. But by the end, I would just laugh. I would just be laughing because it's like it's not me. [laughs] It's a projection. What I hope my book did and what I do often when I'm dealing with this kind of work is I remember that it has nothing to do with me. Sharon Olds, who was my teacher at the time when I was writing Voyage, she called me after she read a few of the poems in Voyage. She's like, “Are you okay?” I just started laughing hysterically. I was like, “I'm fine. The question is, are you okay?” You know, that's the question. So these persona poems for me, there are moments where I walk into Cavafy's body in this new book and there are moments when I walk out. There are moments when I'm just walking with him. There are moments when he walks into my life too. I feel very comfortable with that. You know, I'm about to sound really, really crass, but the blood of every nation in the world is running through my body, darling. There's not a continent that isn't present in my body and in the bodies of so many other people, you included. So my very cells question, “What can a nation possibly be?” If you wanted to separate me and segregate me, you would have to split my body in so many parts, which I know so many people would like to do now to us. It's again about that decolonization thing. I'm very careful about writing into other people's bodies and realities because I don't want to use that. I hate it when people do that poorly, but when they do it well, that's a different thing. When you do it in a way that is a contribution to the history of poetry and humanity, and it pulls us further into something deeper, like Rita Dove's poem that you just mentioned, that's a whole other thing. That's a gift. You said something about Cavafy as a white male. I want to say a couple of things. When the Cavafy Festival took place in New York, there was a conference that was arranged with the festival at Columbia University by this great scholar, Stathis. I was on a panel with the great poet Brenda Shaughnessy. I can't tell you how many people came from Greece, but also from the Greek diaspora, for the conference that was packed. Everybody's talking. I just said, "You know, I don't consider you guys white. I just don't." When I was in Athens, I was like, "These people look just like my mother, who wasn't biracial." A lot of people like to look at people from the United States who are light-skinned and think, "Oh, they must be biracial." No, my mother wasn't biracial, and neither was her mother. I couldn't tell the difference between the two. I say this a lot to my Arab friends too. It's like, “Why do you dissect yourself from Africa? Why?” Right? While I understand that Greeks consider themselves to be white, I also think about that great book How the Irish Became White. I mean, I think a lot of people became white. You know, Oscar Wilde came to the United States in 1882 as a descendant—his mother was a great Irish nationalist. The United States messed his head up so badly because he saw a lynching, because his valet had to be segregated during Jim Crow. Like, all of these things—race is trauma. The idea of race is trauma. It's also a lie. So Cavafy's whiteness was never an issue for me. It was never something I even considered. What I thought was, and especially when you look at his pictures, what I thought was, “What a hottie. Can you imagine?” [laughter] Right? Like, oh, and then you look at photographs of men in Alexandria at the same time, Egyptian men. But they were also—you’re like, these are port places. If you really want to see what a farce race is, go live in a port city. New Orleans is a port city. Blackness is vaster than we can possibly imagine, I guess, is what I'm trying to say. Maybe because I'm raised and descended from Afro-Creoles, we don't take race very seriously. We don't. I mean, we take our Blackness very seriously—I mean, our culture. But the idea that race is a fixed category, oh, please. You know, I mean, Pope Leo, that was only a surprise for people who weren't from Louisiana. You know, Forster—Forster loved Cavafy. He had a thing for him. E.M. Forster. He had a huge, huge, huge thing for him. [laughter] I wouldn't have known that either if I hadn't gone to the archives in Athens. There's a letter from Forster to Cavafy where Forster—the E.M. Forster—is groveling to Cavafy because—I love this so much—Forster had published a poem of Cavafy's and he messed up one of Cavafy's line breaks.

DN: Oh.

RCL: He goes on and on and on about how sorry he is. One of my students at the time, I was teaching this other book by Forster. These three white men in my class were like, "Why the hell are you teaching us Forster?" I was like, "What could you possibly mean?" "Well, why are you teaching this dead white man?" I was like, "Have you read him, first of all?" They were like, "No." I said, "Okay. So first of all, Forster can write his ass off. I mean, you look at any of his sentences and you will have your head chopped off. If you finish the whole novel, you'll be a new person at the end. But more importantly, more importantly, why don't you steal from the thief? I don't not read something because, oh, this person is that, this person was that." I mean, like Solmaz's work, brilliant. She didn't go, "Oh, this stuff is horrible," and it is horrible. She went, "Oh, this stuff is horrible, let me dissect it like an atom." I don't want to avoid writers because they're dead and white. I won't do that. Just like I won't avoid writers who are dead and Black who I can't stand because there are some dead Black writers who said horrific things about Black women. There's this pretense of purity that we have that we'll never get. For me, the gift of being Black is that you do what you got to do. I do that in my lines and in the projects I take on, too. You know, you get around it.

DN: Well, let's hear Cavafy in Compton.

RCL: Sure. To the readers who don't know this poem, the original poem, it's a rough translation of Cavafy's poem about handkerchiefs. But I changed the gender, changed the time period to Compton, California in 1975. So it's called Cavafy in Compton/Closet Anthem Self-Portrait at 16, 1979. A translation of Konstantin Cavafy’s “I was asking about the quality”

[Robin Coste Lewis reads a poem called Cavafy in Compton]

DN: We've been listening to Robin Coste Lewis read from Archive of Desire. So in a recent lecture you gave at CalArts, where you mentioned, just as you've mentioned today, how if you could go back to school, you would pursue biology, that the history of cells seems more important than any other history. In that lecture, you say, "The cell is the baddest motherfucker of all. The ultimate drag queen. I'm going to be this. I'm going to be this. I'm going to be this. I'm going to be everything." Your epilogue is amazing in this book. Part of what it is looking at is the performativity of gender in your own family and how your parents had to perform gender, and how they provided you and your sister a genderless childhood pre-puberty, and a whole bunch of other ways in which code switching is happening around gender. Mendelsohn describes Cavafy as having a fluidity that reminded me of your epilogue, both around selfhood and also around history. This is exemplified also, I think, in his engagement with religion. Because of his interest in ancient pagan Hellenistic culture, but also in early Christianity, much has been written about how he positions himself in relationship to both. He has a sequence of poems about the Emperor Julian, who rejected Christianity and wanted to hearken back to pre-Christian times for inspiration. Mendelsohn says many readers mistake Cavafy's interest in Julian as admiration, but that Cavafy actually found Julian's pagan revivalism as moralistic and restrictive, and that the early Antioch and Greek Christians were, in Cavafy's mind, counterintuitively perhaps, the true heirs of pagan Hellenism. Joseph Brodsky similarly said about Cavafy in the 70s, "To reduce Cavafy to a homosexual who felt uneasy about Christianity would be simplistic. For that matter, he felt no cozier with paganism. He was perceptive enough to know that he had been born with the mixture of both in his veins, born into this mixture. He felt the tension. It was not the fault of either one, but of both. His was not a question of split loyalty. Cavafy's way was neither Christian nor pagan." In light of this, we have a question for you from one of your collaborators in the original performed version of Archive of Desire—the composer, pianist, band leader, MacArthur Genius Grant recipient, Vijay Iyer. He's been voted Jazz Artist of the Year many times in the annual DownBeat International Jazz Critics Poll. He has collaborated with everyone from Amiri Baraka to Zakir Hussain to DJ Spooky to Robin Coste Lewis. Here's a question for you from Vijay.

Vijay Iyer: Hello, Robin. It's Vijay. I'm so proud to be a part of this beautiful project with you and to get to make music that supports your gorgeous, sensual, rich, and revelatory poems. My question is about divinity and the divine. I know that you went to divinity school and that you studied ancient texts and Sanskrit having to do with different spiritual traditions. Maybe you could say something about the spiritual dimension in your work and especially how it might relate to those years of study. I am grateful for everything that you do. Thank you.