Rodrigo Fresán : Melvill

How can a novel set during one brief moment near the end of Herman Melville’s father’s life, a moment lost to history and now fully overshadowed by his son’s enduring literary legacy, become a portal to discuss the world entire? Melvill is a novel about reading and writing, about parenthood and legacy, about madness and memory, about time and ghosts and the dead who never die. Jorge Luis Borges once called Moby Dick an “infinite novel,” one that “page by page, expands and even exceeds the size of the cosmos.” And today’s conversation with Rodrigo Fresán seems animated by this very spirit. Somehow a conversation about Herman Melville’s father not only becomes a deep meditation on Moby Dick but also, at the very same time, at the very same moment, a meditation on Argentinian literature, on imagination and place, on style and plot, on vampires and footnotes, on Borges, Bolaño, Bob Dylan, Vladimir Nabokov, and on and on into the infinite cosmos.

For those subscribed to the bonus audio archive, today’s contribution is a long-form conversation with Melvill‘s translator Will Vanderhyden. We explore Will and Rodrigo’s ongoing collaboration and friendship, the challenges and joys of translating Rodrigo’s work and Will’s own journey as a translator. To learn more about the bonus audio and the other potential benefits of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally here is the Bookshop for today’s episode.

Transcript

David Naimon: It's hard to be a reader in 2024. Before getting into a good book, you have to somehow ignore your inbox, avoid doom-scrolling, break free from the algorithm, and then just when you're getting into it, there's an alert that pulls you back out. That's why reading technology company Sol designed the Sol Reader, a wearable e-reader that helps you shut out the world and get back to reading. You put on the Sol Reader like a pair of glasses. Just slip it on, lay back, and see the pages of a book right there in front of you on an E Ink screen. Think of it as noise canceling for your eyes. No distractions, just words. Check out the Sol Reader at solreader.com to start reading without distraction. If you use the code COVERS15 at checkout, you'll receive 15% off your purchase of Sol Reader limited edition. Today's episode is also brought to you by The World With Its Mouth Open, an original and powerful debut collection by Zahid Rafiq, called “Restrained and revelatory” by Omar El Akkad and “Tenderly and exquisitely rendered” by Sindya Bhanoo, the eleven stories, The World With Its Mouth Open follows the inner lives of people in Kashmir as they journey through an uncertain terrain of their day-to-day lives, fractured from years of war. From an expectant mother walking on a precarious road to two dogs wandering the city, the stories in The World With Its Mouth Open are a testament to the life, beauty, and humor that offer refuge in the face of devastation. Helena María Viramontes praises, “Reading each story, my heart pumps and I recognize myself.” The World With Its Mouth Open is available now from Tin House. At the beginning of the year, the most improbable thematic connection emerged across multiple episodes. A connection that was not at all by design, but one that has never appeared otherwise. That of cannibalism, where first when I was talking to Mathias Énard about his book The Annual Banquet of the Gravediggers’ Guild, we touched upon a character in another of his books, who was studying the corpse wine drinkers of Borneo and both how the corpse wine was used and what it signified. This was soon followed by Álvaro Enrigue, wherein his imagining into the many undocumented days Hernán Cortés spent as a guest in Moctezuma's palace in his novel You Dreamed of Empires, we revisited the question of ritual cannibalism among the Aztec peoples, the way the accusation of it was weaponized, and also the way Montaigne in France recontextualized this cannibalism to opposite ends. Then when talking to Anne de Marcken about her book, It Lasts Forever and Then It's Over, winner of the 2024 Ursula K. Le Guin Prize in Fiction, we talk even more about cannibalism, both in the realm of her zombie protagonist and also in the real world of the United States. I bring this up because I wonder if we are in the beginnings of another trend, not one quite as improbable, for sure. But today's conversation with Rodrigo Fresán does not revisit cannibalism, even if his book about Herman Melville's father does actually have a vampire character within it. But the focus on Melvill in today's conversation comes right after my conversation last month with Dionne Brand, where we talk favorably about Melville's story, Benito Cereno, in relation to the portrayal of Black life on the page. That isn't much of a trend, I admit. Even if we reach back to the conversation with Cecilia Vicuña, where we explore the fantastical seeming yet true relationship between deer and whales, a prehistoric deer being the evolutionary link between the whale’s land-based ancestors and the whales we know today. But perhaps what makes this wisp of a trend leap out is actually how strange it is that Melvill doesn't come up much more often on the show. There certainly is no better conversation than today's to remedy this in a deep way and also in many surprising ways. It's a conversation that is both deeply about Melvill and deeply at the very same time, sometimes in the very same moments about Argentinian literature. I should also mention that from long ago in the bonus audio archive is this really incredible reading by Christine Schutt of Elizabeth Hardwick's writings on Moby-Dick. If you subscribe to the bonus audio and you missed it, it is definitely worth seeking out. One of the great treats for me to share today with bonus audio archive subscribers is the long-form conversation with Rodrigo's translator Will Vanderhyden. It's a treat for me because Will and I have been talking on and off for years and anticipating the possibility of talking together for literally years. Given the unusually close relationship that Will and Rodrigo have with each other and how formative Will's encounter with Rodrigo's work was to his life trajectory as a translator, it's an incredible compliment to today's conversation with Rodrigo. It also joins many long-form translator conversations in the bonus archive. Thinking of just the Spanish language translators alone, it includes Megan McDowell about translating Mariana Enriquez and another time about translating Alejandro Zambra. It includes Sarah Booker and Suzanne Jill Levine, both about translating different books by Cristina Rivera Garza. It includes Sophie Hughes about Fernanda Melchor, Michelle Gil-Montero about Valerie Mejer Caso, and many others. The bonus audio is only one of many possible things to choose from, from the Tin House Early Reader subscription to rare collectibles from past guests. But regardless of what you choose, every supporter is invited to join our collective brainstorm of who to invite on the show going forward, something that significantly influences the future of the show. Every listener-supporter gets resources with every episode of what I discovered in preparing, what we discussed during the conversation, and where to explore once you're done listening. You can check it all out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today's conversation with Rodrigo Fresán.

[Music]

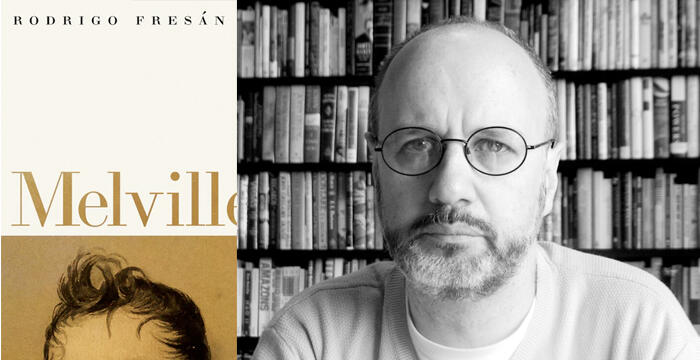

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest is Argentinian writer and critic Rodrigo Fresán. Born in Argentina and spending his adolescence in Venezuela, Fresán has called Barcelona home since the late 1990s. His debut book Historia Argentina was one of the first books of his generation to deal with the years of the dictatorship in Argentina using dark humor, irony, and sarcasm. This book, by an as-of-yet unknown author immediately upon its release, was number one on the bestseller list. Spanish critic Ignacio Echevarría called it “a manual of instructions from which to devise the pattern of a mutant literature and a book that contains the germ of all of Fresán’s subsequent books.” Historia Argentina and the five books that followed it in the subsequent decade have not yet been translated into English, his 2003 novel Kensington Gardens was the first of his books to be translated, a translation by Natasha Wimmer. Everything since then has been translated by Will Vanderhyden for Open Letter Books: The Bottom of the Sky, an homage to the history of American science fiction, described as a Kurt Vonnegut novel told by David Lynch through the lens of Philip K. Dick. Also, to borrow his translator's description, his nearly 2,000-page, three-headed monster and masterwork, the trilogy, The Invented Part, The Dreamed Part, The Remembered Part. The Invented Part, winner of the 2018 Best Translated Book Award, was described in Kirkus' starred review as follows, "A tour de force from Argentinian writer Fresán, charting a course from confusion to confusion and back again. Think of it as a portrait of the artist as a young cultural omnivore grown old, under whose lens Heraclitus, Einstein, and Looney Tunes all have more or less equal footing. An exemplary postmodern novel that is both literature and entertainment.” In 2017, Fresán won the Prix Roger Callois for his body of work, joining past winners Édouard Glissant, César Aira, and Carlos Fuentes, to name a few. Beyond the writing of novels and stories, Fresán worked as a journalist from a young age, writing about food, music, cinema, and literature. He has interviewed many writers from Martin Amis to Salman Rushdie. He has written the prologues to many American writers' works when translated into Spanish, from John Cheever to Carson McCullers, and he is the translator of the Spanish version of Denis Johnson's Jesus' Son. He was also, upon moving to Barcelona, the editor of the Roja & Negra series of crime novels published by Random House in Spain. Rodrigo Fresán is here today to talk about his latest book to be brought into English by Will Vanderhyden for Open Letter Books, his novel Melvill. Publishers Weekly in its starred review says, "Argentine writer Fresan focuses his visionary latest on the inner life of author Herman Melville and the exploits of his tormented father, Allan." The review ends declaratively, "This is a masterpiece," and Kirkus in its starred review calls Melvill “An elegant, meditative story about storytelling—for lives are, Fresán writes, ‘really, books of stories.’” And finally, past Between the Covers’ guest, Mariana Enriquez says, “Melvill is an invocation, a séance: the voices of the father and the son cross time to speak of failure and genius, of the mysteries of the whale and the vampires in the night sky. Fresan conjures up these heirs of sadness and obsession with hypnotic writing of rare beauty. This novel is an invitation to walk on ice.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Rodrigo Fresán.

Rodrigo Fresán: Hello, thanks for having me. What a life.

DN: [Laughs] It really is.

RF: I don’t know how I should feel, if to get excited or depressed. [laughter]

DN: So as a prelude to asking you about what captured your imagination about writing a novel that centers brief moments in the life of Herman Melville's father, I first wanted to ask you about Herman Melville himself. There are quite a few Spanish language authors who you have known or who you care about that themselves care about Melville. Borges has a poem entitled Herman Melville and he called Moby Dick an infinite novel, a narrative that page by page expands and even exceeds the size of the cosmos. Enrique Vila-Matas, who engages deeply with Bartleby, also says about his own writing, "It's as if my characters form part of the damned crew of the Pequod and continue to pursue Moby Dick in the twenty-first century." Bolaño, when asked by Mexican Playboy to pick the five books that most marked his life, said, "In reality the five books are more like 5,000. I'll mention these only as the tip of the spear: Don Quixote, Moby Dick. The complete works of Borges, Hopscotch, A Confederacy of Dunces." And in his book, Entre paréntesis, he says of Melville and Twain, “All American novelists, including those who write in Spanish, at some point in their lives get a glimpse of two books on the horizon, they are two roads, two structures, and two arguments. Sometimes: two destinies. One is Moby Dick by Melville, the other is The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain.” Talk to us about what your relationship and your interest is in Melville the writer. Why Melville?

RF: Well, first of all, in the beginning, it's Moby Dick, an abridged version for children or young readers and it's just the part of the story of going after a whale under the orders of a mad captain, and that's enough, really.

DN: [Laughs] For sure, for a kid.

RF: Then you grow up, and books start to grow up also with you and you read the complete version and you discover that everything's there. Well, I think really that I have this theory about the roots of the great American novel, that sort of spectra always called. I think that there are like four books, original books that they work as the areas for successive variations to history and time. One of them is Moby Dick, that it's the multi-symbolic novel. Ahab can symbolize anything. The whale can symbolize anything. Queequeg can symbolize everything. Ishmael, the Pequod. I mean, it's like a symbolic novel and you can see all the novels that fail after Moby Dick. The other one is The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne, which is the novel of Puritanical rights and sexual repression. The other one of course is the road novel, the first person, very satirical that takes derided by the early [inaudible], it's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and the fourth one is the one of the writer that goes abroad and opens himself to the world and to the old world that is portrayed as a lady. I think that in these four novels, you have the whole thing, the whole game of what the different models of great American novels are. There's a fifth one, for me, it's the real and more authentic American novel, it's Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov. Because I think there's nothing more American than a foreigner writing in English and revitalizing the whole language and discovering the motels, lots of landscapes that were already there, but they weren't yet in fiction.

DN: I love that.

RF: And to finish the thing, I think that the distinctive and astonishing thing about Moby Dick is that it contains everything that went before Moby Dick in literature and anticipates everything that will come after Moby Dick. There's a part in Melvill in the novel where an old Herman Melville goes into a tavern in the port of New York, and there are sailors there singing like sea shanties and ballads. In fact, they're singing songs from the White Album by the Beatles, [laughter] which I think is the Moby Dick of pop music because it's completely white, the cover has a whale for starters. [laughter] It's huge, it's big, it has multitude of styles and references and influences and it also contains everything that came before and everything that will come later like heavy rock, punk rock, indie rock, whatever you want to listen to.

DN: That's amazing. Well, when I talked to Hernan Diaz for the show about his book, Trust, I read his earlier book on Borges as part of my preparation to talk to him. It was a book that really opened my eyes to how much the literature of the United States influenced Borges. Diaz says it is hard to think of two writers that shaped Borges more than Edgar Allan Poe and Walt Whitman. Borges himself says that all that is specifically modern and contemporary poetry comes from these "two North Americans of genius." Then when I talked with Argentinian writer Mariana Enriquez when she was on the show, we talked about how she felt that it wasn't just Borges, but that more broadly, the tradition of the fantastical in Argentina was usually not place-based, and that what appealed to her about North American horror and horror writers was that the horror came up from the ground, the particulars of the place, of the soil and the histories there, of what was buried there, and that she wanted to write an Argentinian horror like that, where the specifics of place are what produces the horror in the narrative. Thinking of your engagement with Melvill or in other books, the history of American science fiction, or your longstanding engagement with Bob Dylan, you yourself have said, "I consider myself very Argentine in the sense that I don't consider myself Argentine at all," and “I think that, while other literatures from Latin America and even from Spain have their roots firmly in the ground where they take place, Argentine literature’s roots are buried in the wall and, more concretely, in the wall of the library. The tradition of the Argentine writer is built more on the foundation of the figure of the reader than the figure of the writer.” I was hoping you could talk a little bit about this, both what it means to build a tradition on the figure of the reader, and also maybe if you have any theories why you think this tradition rose in Argentina of all places.

RF: I don't think it's only an Argentinian thing, but maybe it has to be with Argentina, and when I say Argentina, I say Buenos Aires and Montevideo and Uruguay, that sort of territory. It's pretty insular. They always wanted to be, I think, not part of Latin America, but part of some lost province of Europe and the United States, like some sort of Atlantis, that it didn't sink, but it went far, far, far away. You mentioned Borges, and Borges, and all my favorite Argentinian writers, they're basically super-readers. I mean, all their fiction or the literature, it's built around the idea of reading and writing. All his fictions are filled up with writers and readers as main characters. In fact, there's this essay by Borges that is titled The Argentine Writer and Tradition. I'm going to paraphrase, I don't remember the quote exactly. But at the end, he says that it's a great commandment or a great suggestion or a great advice. He says something like, [we have to rethink ourselves to the fatality of being Argentinians so we have the consolation that our whole being is the whole universe, so you don't have to base yourself in your territory,] and if you do some sort of very, very superficial review, you'll find out that all great Argentinian novels are very strange formally, are fragmented, are sort of kaleidoscopic, are not exactly taking place in reality. That's very different to the idea of the great Mexican novel, or the great Colombian novel, or the great Peruvian novel, or the great Chilean novel, where they have some sort of, not a mandate, but some sort of duty to be witnesses to their time and their region. We in Argentina, we always want to run away, we want to escape the place where we were born. In fact, I think that when just introduced me and said, Argentinian writer, I'm 61 years old now, so I'm starting to [inaudible] the twilight horizon, [laughter] and to discover that it's going to be much more important the place where you're going to die as a writer than the place where you were born, I mean you have no decision in the place where you were born. It's some sort of chance at your parent’s meeting and your parents being born somewhere. But the place where you end up living and dying I think is much more important and much more formative. You live in your library also. It's the real homeland for you. The things you read are inevitably going to influence the things you write and I really like American literature and British literature, like Borges.

DN: Yeah, yeah. In the acknowledgments and end notes of this book, Melvill, you quote a line from another one of your books, from the book The Remembered Part, and that line goes, "And yes, he'd once fantasized about writing a novella about Herman Melville's father, a beautiful loser walking across the frozen Hudson River to return to his family and die among them amid deliriums, and with his young son seeing it all and taking notes and thinking of the whiteness of the snow and the ice.” That is in fact a description of the book we are discussing prior to you having published it. How and why did you end up fantasizing about Melville's father in this way? Not only a figure that no one thinks about, but also this very tiny slice of his life at the very end.

RF: I really like the idea that it's very tiny. The original idea for the book, it was going to take place in just that night with Allan Melville crossing the frozen Hudson. I sort of advanced it and put it in The Remembered Part. The main character of The Remembered Part is a writer that can't write anymore. I was really worried about somebody stealing that idea from me, that someone was going to make the book about Allan Melville crossing the frozen Hudson. It was a gift to my character who can’t write anymore. At the same time, it was some sort of, “Okay, this is mine, and maybe I'm going to do it so don't touch it.” [laughter] I read the biography of Melville by [Andrew] Delbanco, I think. He mentioned it here, it's two, three lines, Allan Melville, Herman Melville's father died when Herman Melville was like 10, 11 years old. He didn't take much pace in the life of Melville. That gave me a lot of territory in order to invent. There's some very interesting data in the huge two-volume Herman Melville biography by Hershel Parker where he deals with Albany, the immigration and the colonization of Albany and all the Dutch families going to Manhattan and building their businesses on the shores of the Hudson River. But it really, really intrigued me, that idea, in all my books, the father and son thing, it has some relevance. Maybe that's the result of having listened to a lot of Cat Stevens Father & Son when I was a kid. I don't know. Or maybe having a very complicated life with my parents who belong to a 60s utopical generation who were bound to change everything. In fact, it didn't work out that way.

DN: No, indeed it did not.

RF: No, imagine there's no heaven. [laughter]

DN: Yeah.

RF: It's not easy if you try.

DN: [Laughs] Father & Son was a big part of my soundtrack when I was a little kid too. Part one of this book is titled The Father of the Son and is written about the life of Herman Melville's father, Allan. But this section of the book is heavily footnoted, and it turns out that these footnotes in this section about the life of Allan are written by his son, Herman. Even in this 70-page section about the father, in many ways, the footnotes and the son's voice dominate from below. Obviously, Allan is a mere footnote in Herman Melville's life from our vantage point, a positionality you've reversed here. But your use of footnotes is not specific to this project. If we leap back 20 years to your English debut, Kensington Gardens, there is the line, "Children begin as footnotes to their parents, and parents end up being footnotes to their children." That book two decades ago shares this interest in children and parents too. But even reading your essays, for instance, your essay in The Believer about your friendship with Bolaño, it too has many, sometimes quite voluminous footnotes. This element of your work that points us both to more information, but also points us to more information away from where our eyes are resting at the moment, it feels like one defining character of your writing. I was hoping we could spend a moment talking about where this impulse comes from for you, you think, and to what end.

RF: I didn't remember having written that on Kensington Gardens. I'm completely shocked about that instead, [laughs] in light of what I did after with Melvill. Well, the footnotes, it's not David Foster Wallace influenced. It's Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire, I think. In Pale Fire, the footnotes are all at the end, are not technically rigorous footnotes because they’re not at the foot. But I think that's the idea of some sort of distorted witness commenting on what is supposedly the official story but not so much in a way. I love footnotes. [laughter]

DN: Well, I could tell. [laughter]

RF: There are many, many, many, many, many, many people that really hate them and when you have to compose the book for printing, it's trouble. There's a huge footnote at the beginning of the third part of Melvill that I wanted to make it the footnote growing and going into the main text.

DN: Yeah, I love that moment when the footnote becomes the main text.

RF: Well, my publishers hate it because it was very difficult to balance the footnote with the text, but I think it's worthwhile. I love reading footnotes. If you think our whole lives, our whole reality is lived through footnotes. I mean, when you're talking to someone, you're always looking down and trying to see the small print about what they're saying to you.

DN: Yeah. Well, one of the biggest laughs I had was the page in that section that had only one sentence on it, surrounded by white space otherwise. There's one sentence on a page that goes, "The son's name is Herman." The footnote way at the bottom in small print is, "Call me Herman." You said in an interview about this book that beyond the Melvilliana, its themes are the same as all your recent writing, namely the themes being, in your words, “reading and writing, the mysteries of the literary vocation and parenthood.” Thinking of that quote from 20 years ago in Kensington Gardens about children and parents in relation to footnotes, all the way through the most recent book, which is again a deep engagement with being a father and being a son, where not only is Herman as a child at his father's deathbed, but as an adult in this same book, he's haunted by the death of his two sons. You suggest Billy Budd is his fictionally recreated son, "innocent, angelic, beautiful, and condemned to die, summarily executed." And there's the question of legacy and what is inherited, particularly around his father's madness, which you describe as Allan subjecting his son to his white delirium. Herman is later accused by his critics, critics of his books, that they've been affected by an inherited madness from his father. Late in the book there's this wonderful line, “It is not parents who write their children, but the children who rewrite their parents.” I know you've already spoken to this preoccupation of father and son and parenthood, but does this spark any other further thoughts about this enduring interest, which goes decades across your career?

RF: God, I don't think I want to think about it. [laughter] I feel like I'm at the shrink now. [laughter]

DN: Do you want to lie down on the couch?

RF: I'm Argentinian, my mother is a shrink, but I've never participated in that very Argentinian right that it's going to synchronize us. But first of all, and in order to not answer your question, I want to say that very nice for me to hear quotes to your reading from Melvill, are in fact quotes of a book that Will Vanderhyden wrote. I mean, he's an amazing translator and Chad Post and [inaudible] are very daring publishers. I want to say this, I really am really grateful from the bottom of my heart and brain to them. I'm trying to gain some time in order not to answer your question. [laughter]

DN: Well, let me ask you something that has nothing to do with the book that I'm curious about is, why is psychoanalysis so big in Argentina?

RF: Who knows? Who knows it's a mystery.

DN: It is.

RF: Yeah, Ingmar Bergman films were big before everywhere in the world. I mean, I don't know. I don't know. I don't know why. Maybe Argentinians like a lot to talk about themselves but I never understood being a writer, when they asked me why I've never went to a shrink being an Argentinian, I always answer the same, “I'm a writer. I'm not going to pay for telling stories. You have to pay me.” [laughter]

DN: You have to pay me. So you'd go to a psychoanalysis if you were paid?

RF: I don't think so. No.

DN: [Laughs] You wouldn't go there either?

RF: Well, yeah.

DN: Maybe. [laughs]

RF: No, what you said about the terms of legacy and parents and father and son, and if you go to the beginning of times and to the first examples of what's considered a literature or fiction, it's already there. Well, it's in the Bible, Father and Son.

DN: Yeah, from the beginning.

RF: Yeah, and you have all these Greek Roman gods having sons and killing each other all the time and plotting against each other.

DN: Yeah. The first section, The Father of the Son ends with the father's death. Section two, titled Glaciology; Or, the Transparency of the Ice, in that section we're back with the living Allan Melville, the father, we're in the father's consciousness, but this time without any footnotes by his son. It dilates this real moment in the father's life where he walks across the frozen Hudson River. Yet, even though it's dilating this real moment, it's the most fantastical portion of the book, and also the most, I think, philosophical and meditative. He uses science and the science of glaciers to give account of his nature with lines like, "Is ice the substance that the memory is made of, or is memory something you envelop in ice to keep from losing it?" There's a long meditation on the various colors of ice, on whiteness for sure, but ultimately a long investigation of the color blue, as well as the ancient world's supposed color blindness to blue, one theory behind why Homer described the sea as wine-dark. I love this long meditation on ice partially because I think of this time period in human history, the 19th century, being one where the human fantastical imagination was projected onto ice more than anywhere else. We knew of the poles, but they had not yet been explored. They were unknown and unmapped, but our imagination lived there. Like some people then thought that the Garden of Eden was there and when you got close enough, or far away enough from the equator, the migration of birds reversed and went polar, and the weather got warmer rather than colder. This isn't in your book, but this is in the milieu of respectable thought at the time. Others thought there were holes in the poles. Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth imagined we reached the center through these holes. Edgar Allan Poe's only novel, which follows a voyage to get to the pole, instead almost there encounters an island of the blackest of black people, so black they even have black teeth, and then ultimately, when they get as far as they can go, they encounter this immense impossibly white creature or phantom or phantom creature. But talk to us about how this section for you, this section most deeply in the consciousness of Allan Melville, becomes a chapter on glaciology and on ice. Is it because of these elements? Is it because of the time period, or is it something entirely different?

RF: First of all, there's some sort of homage to the chapter in Moby Dick about the white and the whiteness. It starts like this. But there's also all you mentioned, especially Gordon Pym and follow up the Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness that sort of continues Gordon Pym. As we said or insinuated at the beginning, there's a really interesting thing about Argentinian literature that I'm sure it's the only one in Spanish, but I think it's in any language, in all languages in the world and probably in the galaxy, that all their huge totemical, monolithical writers, they practice the fantastic literature or fiction of the strange, which is not very common. I mean, for us Argentinian writers, when they talk about genres, this is fantasy or this is horror, for us, for all of us, it's just literature. I mean, we don't have that compartments as permanently drawn as in other languages or in other countries. It's the most fantastical part because there's also that grand tour story when Allan Melville goes to Europe that starts as the typical American and a grand tour in order to receive some education or uneducation, whatever you want, and then go back to the new world. But I always wanted to write since the beginning of times when I was just a reader who wanted to be a writer, and I'm talking five years old, I always wanted to write a vampire story because Dracula was one of the huge books when I was growing up. In fact, it was the first, not abridged edition of a book that I read was like seven, eight years old and I felt like, “Okay, I'm reading now the real thing, not the condensed infantilized edition for kids.” Iinfantilized wanted to write a vampire story and a ghost story. That's my new novel that came out here in January in Spanish, The Style of the Elements. It's like some sort of non-autobiographical story of my childhood and teenage years, understanding the idea of the past as the most real and gigantic ghosts of all.

DN: Well, I love this section and let's spend a moment a little more with the vampire. I like that you connect, I mean, it's an obvious connection, but I like that you draw forward Poe to Lovecraft and you have this supernatural being accompanying Allan, Nico C who, among other things, is meditating alongside Allan on his own nature. He isn't a vampire, he says. He doesn't need to feed on humans, even as beings like him in his mind, they feed humans. That he's more like a phantasm plus a vampire, a phanpiro, he calls himself. Him and his fellow creatures that haunt the human world are actually far happier to exist than we like to think. At one point in the novel, you write about how the dead take up far more space than the living, that them not being there is like being everywhere. I thought about Nico like this, even though it doesn't seem like Allan Melville is being haunted here by someone close to him, I also thought about you the author and your biography when Nico C says that his kind are not undead nor are they dead who come back, but rather they are beings who undie. It reminded me of one interview where I learned that you yourself were pronounced dead at birth.

RF: [inaudible] [laughter]

DN: Lastly, I thought about something you wrote about Bolaño that “one of his recurring ideas was his suspicion that he had died 10 years earlier in a hospital in Girona,” when he was diagnosed with a severe case of pancreatitis and that everything that had happened to him in the last decade, children and wife and books, was just his final hallucination, the merciful prolongation of the last seconds of a dying man. Which really sounds like a description of Allan Melville's hallucination here, that perhaps Nico C was Melville's hallucination, or that Bolaño's suspicion was an influence on this section of the book. But either way, talk to us a little bit more about Nico C, and also whether you yourself, given your history at birth, are a vampiro.

RF: [Laughs] Well, Nico C, first of all, is an Argentinian, the only character in the whole book that comes from Argentina. I think it's because it's what I told you, the idea of Argentina being like some sort of unbelievable, fantastic territory with pretty strange characters and people who usually died abroad. Borges died abroad, Che Guevara died abroad, Carlos Gardel, the tango singer died abroad, Evita died in Argentina, but her corpse traveled everywhere. I don't know if you know that story, but it's some sort of very dark myth of Argentine history about Evita’s embalmed body traveling all over the world and being chased like some sort of holy relic. In all the fictions, I really like the presence or the idea of one character being wiser than all the rest and knowing more and having some sort of supernatural knowledge of the whole thing that it's happening. In a way, I like to think it symbolizes the writer maybe. You can be lost while writing a book for a moment, but I agree with Nabokov, which is one of my favorite writers, when he says, he used to say, "I despise those writers that said the characters take me where they want to go and I go after them. Bullshit. You have to be in control." So maybe some sort of superstitious thing or some sort of cabalistic movement of putting in there someone who knows everything in order to help me to know everything too.

DN: Speaking of people dying abroad, I've visited Cortázar's grave in Paris. Did he die in France? Do you know?

RF: He died in France. He wasn't born in Argentina. He was born in Belgium. He was technically not an Argentinian, which is a very Argentinian thing to be.

DN: I love that. Well, my suggesting that you are possibly a vampiro, my tongue-in-cheek version of a real impulse of many readers to try to anchor their encounter of reading fiction within the real-life facts of the author, this is an impulse that you spend a good deal of time in the afterword interrogating. You do this at length, this impulse of some people to try to unearth real-life correspondences. You critique novels narrated by historical characters as superficial, even as we are reading a possible example of one. You lament the trend of readers having more interest in the life of the author than actually reading the author, where everything has to have a reason to be real. You say in no uncertain terms that the protagonist in your trilogy, called The Writer, is not a distorted version of you. But even though this approach to reading and understanding fiction that some of these readers do bothers you, you don't simply avoid writing historical characters within your fiction, because here we are with Allan and Herman Melville, and you yourself invite this mistake of reading, I think, by giving The Writer in your trilogy many of the most basic details of your own life, while at the same time you have you as yourself make a cameo in the book to distinguish the two of you. So there is a push and pull that feels in a way like the inverse of what Philip Roth did in his book, The Facts, where for most of his career, his protagonists, they also shared the most basic details of his own life, so that readers often presumed, sometimes quite falsely, that the thoughts and events of Nathan Zuckerman or Alexander Portnoy were from Philip Roth’s real life. Then as a further provocation, he writes this book of nonfiction. It's a minor book of his, The Facts, that details just the bare facts of his childhood.

RF: That book is a footnote to Zuckerman.

DN: Yeah. Then his doppelganger, or his avatar, Nathan Zuckerman writes the epilogue and points out all the distortions and erasures and more in the so-called facts where Roth's real life is being shown to also be a fiction, but shown this by his fictional character. Talk to us about this push and pull where you seem to both invite the reader into something that you also want to push them away from. You spend a good deal of time at the end of this book lamenting certain habits of reading, and yet you set traps for people to possibly read in that same way. To have a character like The Writer, but also yourself in the same book. Or Allan Melville, who really walked across the Hudson, but probably didn't walk across the Hudson with an Argentinian vampire.

RF: Well, guilty as charged. [laughter] You know with all that sort of thing, I have lots of theories and some sort of intellectual, more or less brilliant alibis. But if I have to be completely sincere, I do it because it's fun. It's fun doing it. It's part of what I read when I wanted to be a writer and I find very funny and so the fun, it happened to me with Salinger's short stories and Kurt Vonnegut's books and this idea of the author reading over your shoulder what you are reading because it's what he wrote, but when you read it, it's part of you. It's not any more exactly what he wrote because you're putting in there all your personal things. You mentioned that I was declared dead clinically at the moment of my birth. They always ask me, it's like one of those classical, topical questions to a writer is, “When did you find out that you wanted to be a writer?” The truth is, I've always known since the beginning, I don't have some sort of epiphanic moment or a book I read and I said, “I want to do this.” My mother just told me that thing that I was born dead when I was like 21, 22, she never spoke about it. Then I said to myself, “Maybe it was right there and then when I decided to be a writer because I knew it, how it's going to end.” [laughter] I started for the end part, and I live to tell the tale.

DN: Yeah. You really did.

RF: Yeah.

DN: Well, let me ask that question in a different way because I believe, and it is fun as a reader, these games are fun and I can tell you're having fun, but there's a seriousness too because I can't believe that you would write the afterword and spend so much time on a lengthy afterword talking about this reading habit, which feels like there's a distress there. Maybe you could spend a moment with the impulse to write that afterword, to write about the wrong sorts of questions to ask when you're reading or the wrong sorts of questions to ask when people are reading you?

RF: Yeah, well all my books have very, very long afterwords and they're often criticized for that. I really love writing them. In fact, there's a good friend of mine, Alan Pauls, which is an amazing Argentinian writer who says that my last book just before I died should be all my afterwords put together with the last afterwords about the afterwords. [laughter]

DN: And maybe some footnotes for good measure.

RF: Of course, many footnotes. [laughter] Well, you know the trilogy was written during a very, now it's sort of stopping, I think it was like that in the United States also, here there was a moment with the auto-fiction and everyone telling in strictly real terms about themselves. I think that was the product of a very bad influence. It was social media. It was like people starting telling themselves on social media and said, “Okay, this could be a book.” There was this classical situation for a writer when you go to a party and a guy or a woman comes to you and says, "Oh, my life could be a great novel," and they start telling you to write the book. [laughter] That doesn't happen anymore. Now they come with a manuscript that you already have all their life.

DN: Wow. [laughter] Yeah.

RF: It was some sort of rage against the dying of the light in terms of pure fiction, imaginative fiction, and telling stories, and not telling supposedly realities which are not real. I think that it's much more interesting for any writer to find out in their fictions that the autobiographical things, as you pointed out, hidden or in a subliminal way than you telling the truth all the time or trying to tell the truth. There's one thing that makes me laugh and it makes me cry at the same time is when you read, when you go into Amazon and read the comments of the readers, one of the most frequent “criticizing” is people saying “I couldn't relate to any character,” which is completely absurd to me because you read fiction not to be related. You read fiction to know completely different people than you and knowing them, they become part of your life and your experience. But if you're going to read fiction looking for someone that looks like you, acts like you, and says the same things, we're in deep shit, man.

DN: Yeah. No, I totally agree. It reminds me a little bit, just to go back to Roth for another second, is that his whole career was predicated on this reading mistake when he wrote Portnoy's Complaint and everyone assumed his parents were like the parents in that book and that he was like Portnoy. Apparently, his parents are nothing like the parents in that book. Instead of clarifying that, he decides just to add more inconsequential details of his own life into his characters, but then having them do entirely different things and think different thoughts than he actually thinks. But it made the problem worse because near the end, I mean, his whole career is all these masks. But by the end of his career with a character who I think had like prostate surgery and has incontinence and can't leave his house and everyone is still assuming that's Philip Roth's situation.

RF: Yeah, and in fact, it's one of the things that the third part of Melvill talks about when Melville is clearly worried, tormented, and suffering the possibility of having become a character of himself, not another person anymore.

DN: I love this line from Melville, “Reality only becomes really real after crossing the stormy sea of art and arriving safe and sound to the other shore. Not while we live it or write it, but later, when we read it; and only then does everything become logical and inevitable and we ask ourselves how we failed to see it or see it coming. Thus, everything that one invents ends up (or starts out) being true and, taking place, ends up having taken place to thereby begin to take place.” This makes me think of the manner in which you retell your own life in your nonfiction, whether it's essays or in interviews. For instance, in talking about your own childhood, your home, a place where dissidents would sometimes hide out, your parents being jailed, and how when you were briefly kidnapped by people looking for your parents, you said, "This was the first time you felt like you had a personal experience worthy of being fictionalized," and that, "For me, that is greatest honor you can bestow on reality: to turn it into fiction." And perhaps similarly, what you call the great milestone of your literary formation was actually a real fiction. Your father and you relocate to Venezuela, you're expelled from school, but you don't tell your father. Instead, you pretend you were going to class every day for two years, and it was during that time you went to the library instead. Also, when you were starting out as a writer, you wrote for a credit card magazine called Diners, but under nine different pseudonyms, or your piece and the Believer about your friendship with Bolaño again, where you're meeting at a Kentucky Fried Chicken in Spain during the time he's doing research for 2666, where one passage you write goes, “We leave the Kentucky Fried Chicken and Bolaño goes down the stairs to the platform of his commuter train and I return home and half an hour later Bolaño rings my doorbell, again. He is soaked by the storm and wild-eyed and shaking as if barely withstanding a private earthquake. ‘I’ve killed a man,’ he announces in a deathly voice; and he comes into my apartment, heads for the living room, and asks me to make him a cup of tea. Then he tells me that as he was waiting on the platform, a couple of skinheads had come up to him and tried to rob him, that there was a scuffle, that he managed to get a knife away from one of them and stab the other one near the heart, that then he ran away down corridors and streets, and that he didn’t know what to do next. ‘What should I do? Should I turn myself in?’” As we read further, we discover he's made all this up and not only has he made it all up, he's amazed that you've believed it. You say to us, "And only now do I understand that on that afternoon, without realizing it, I was enjoying the rare privilege of seeing Bolaño writing and writing himself, reading aloud, and—rarest and most precious phenomenon of all—seeing myself inside one of his stories. One of those stories where Bolaño was and is and luckily always will be a Bolaño character.” But to make this more absurdly meta and labyrinthine, you yourself do actually appear in his books as yourself. [laughter] For instance, in 2666, you show up in Kensington Gardens taking notes for your novel Kensington Gardens. Lastly, I want to mention your wonderful piece called Borges and Me, and Me about your two random encounters with Borges. One which, I don't know if these are true, part of me is like, [laughs] it was just kind of wonderful, but one which is entirely improbable as if it were a novel or a fiction is you walking your blind uncle on your arm and from the other direction Borges is approaching in a similar fashion. When you yell, “Borges,” they both look at each other for a moment unseen. The other is during a fight you're having on the street with a girlfriend of yours and you're running after her and in doing so, you run over Borges on the street. You knock him over on his back and you wonder whether you've killed him. You say, “Who knew if this collision with great literature would be the trigger of other stories, or the Fukuyama-esque end of my history as a writer – because what would be the point of writing anything if I went down in history as the person who killed Borges?” All of these stories I think, these non-fictions or supposed non-fictions help me to fully understand these lines from Melvill. Supreme reality and absolute fictions are always seen as rivals but actually are moved by complementary ambitions. I was hoping maybe you could spend a moment on that or on anything else that this epic maximalist question sparks in your brain.

RF: Yeah. Well, it's a very paradoxical thing because all those stories you told, that I told, the Bolaño one and the two with Borges are completely true. But here's the catch. If I want to remember exactly how they were, I have to read the versions I wrote, because I mean, the things I wrote are much more stronger to me and much more real than the actual fact. It sometimes happens to you, that when you write, writing something real, the real things start to fade and the written version takes command. That is going to be the real thing. But I have the distinct memory of, well, of course, I almost killed Borges, going after my girlfriend, [laughter] and I have witnesses. I remember that thing with my blind uncle and Borges and my wife was at home when Bolaño came and do that some sort of perfect Bolaño short story to be told by Rodrigo Fresán. But I really like that. I think that there's some sort of, not exactly poetic justice but literally justice in the idea of the written version being the real version at last, at the end.

DN: I'll definitely point people to these essays of yours because they're really amazing, and I do think it's like an inverse, they add depth to reading your fiction to read the fictional nature of your non-fiction because they're true, but they're hard to believe, the non-fictions, in a reverse of reading Melvill.

RF: Do you know my publisher in Spain was Claudio López de Lamadrid, who died like, I don't know, 2019 already, he always wanted me to write, and maybe I'm going to do it one day, but I'm sort of superstitious. He wanted me to write a book about all my encounters with famous people, which are completely absurd stories and probably unbelievable. But I have witnesses for all of them. [laughter] I don't have any trouble with that. I mean, with Susan Sontag, Hugh Grant, there are lots of very strange--

DN: I really want to read that. [laughs]

RF: Yeah. Probably it's going to be the book that if I publish it, it's going to be the best seller of my life. [laughter] It's going to be the one to sell the most.

DN: I think it will be.

RF: But I'm not comfortable with the idea of these anecdotes that I tell my friends to tell them to everybody. I don't know. I don't think that the life of a writer, the private life, has to be so public in a way.

DN: You know those books that people are bearing for a hundred years in Norway?

RF: Yeah.

DN: Yeah. You should write the book and then they can come out a hundred years after you're gone.

RF: But then I’ll never know if it's going to be a best seller or not. [laughter]

DN: It's a good point.

RF: Yeah. I don't know. I mean, it always comes to the same thing. You were saying it. I mean, all my books for me that when they asked me, which is another pretty uncomfortable moment at parties, when you said, "You're a writer," and they say, "What kind of writing do you do?" And you said, "Fiction." And some people say, "Science fiction," because it sounds fiction. They automatically think that fiction is science fiction, and say, "No," and they say, "But what are your books about?" I think that they all deal with the most transgressive theme that we have today, which is reading and writing. I mean, that's the most subversive theme you can invoke these days.

DN: Well, to stay with the afterword for another moment, it's here that we learn not only just how much research you've done on Herman Melville, but also how much of the book is ultimately a departure from research. In the book itself, we learn about Melville's ancestry, that he comes from legends of the revolution and high colonial society, that his grandfather fought in the Tea Party uprisings and was appointed inspector of customs by George Washington, that back in Scotland his ancestors were nobility and that he was also related to the first woman Scottish writer, among many other writers and artists in his family tree. But whereas these details as well as places and dates are real, many of the actions and thoughts are not only fully invented, but sometimes they are even your own thoughts being spoken or thought by this real historical figure. Touch up on the importance of research for you, why do you do research and how and when does research stop and get left behind? Because we have this strange juxtaposition, obviously. What's the impulse to do the research in the first place to abandon the research?

RF: Well, I think that research in a way is like gasoline in a car. You have to fill up the tank and when it's filled up, you know you'll have enough gasoline to go where you want to go. You don't necessarily use it, but it sort of impregnates everything. There's like some aroma or perfume that really, really helps you in order to be in a place or in a time. John Banville, who's a very good friend of mine, told me that he wrote this novel about Copernicus and Kepler, and he started researching a lot. There was a moment when he discovered he had to invent. I think that you research in order to feel “guilty” for inventing later.

DN: Well, when talking about supreme reality versus absolute fictions, at one point you say, “And from that dynamic friction came the electric ghost of the ones howling in the bones of the others' faces,” which is a reworking of a famous line from Dylan's Visions of Johanna.

RF: I've seen every book of mine.

DN: Yeah, that's what I want to ask you about. I really like discovering Dylan's attributed and unattributed presences in your work, but particularly the marginalia, whether referencing his song, Series of Dreams, or in the new book, this book, an epigraph from his most recent album, a song, Key West, perhaps the most maximalist song on the album, for the first 35-ish years of my life on the planet, I definitely nerded out on Dylan Marginalia going to these weird traveling trade shows at empty shopping malls in the 90s to find illegal bootlegs before he started releasing them officially, and also to find even weirder things like a book in the 70s that examines his album Planet Waves, but it looks at it through a Jewish mystical lens as if the album is a cabalistic album. Each of the 10 songs represents one of the Sephiroth and the cabalistic Tree of Life and it has all these crazy diagrams and illustrations alongside a parsing of the lyrics of each of the songs. You, in this book, mentioned his Moby Dick-inspired song, Bob Dylan's 115th Dream, which I think a lot of people probably know, his bootleg album, Great White Wonder, his Nobel speech, which speaks directly to Moby Dick, but I would imagine more broadly, one reason you might be attracted to him is the very things we've been discussing, the ways he plays with the fiction that is Bob Dylan, his mercurial, ever-shifting nature, the ways he continues to turn away from one audience and then create a new audience. The various masks he's worn, most explicitly in the Renaldo and Clara era, but really his whole career. But tell us in your own words why Bob Dylan is in many of your books, and also, if he's more than a reference and a love, if he's also an influence in some way, and if he is an influence, how is he an influence?

RF: Well, Dylan to me, it's a mystery. If you're a writer, you can resist the idea of a mystery, especially in a world in an age of not a lot of real mysteries around and he was a mystery since the beginning. In terms of Melvillian way of looking, I mean he’s part Ahab, part Ishmael, part Moby Dick, I mean he's all over the place and he's so concentrated at the same time. In fact, I have two very freak encounters with Bob Dylan that maybe they'll be part of that. I told them in The Invented Part, I think that they're completely real about Bob Dylan in his underwear, at his room, washing his blue jeans at his hotel room. But I really like his voice. I think that his voice is his style. Famously, you do not know that Frank Sinatra used to say that he was one of the greatest technical singers of all time. Sinatra said that he couldn't understand people saying that Dylan doesn't sing well. He's a much better singer than myself. He was Frank Sinatra. I really like his phrasing and his ground-unwinding roads of verses. That line from Visions of Johanna, for me it's amazing, and I put him all over my books. There's always a cameo of that, as there's always a cameo of one of my favorite quotes by Kurt Vonnegut in Slaughterhouse-Five when he describes the books of the Tralfamadorians. I think that that's the books I want to write. I want to write Tralfamadorians, because there are a lot of things happening at the same time, and there are some wonderful moments in time, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. But Bob Dylan, I mean, for me, it's like a test. If I meet someone and I ask him, “Do you like Bob Dylan?” The person says, “I hate him,” okay, see you later, never again.

DN: [Laughs] You've said that you're happy to have departed from journalism and interviewing, and you've interviewed so many big writers, but you said you would still like to interview Dylan. Is this something you've pursued or want to pursue?

RF: You can’t pursue it. They have to pursue you. I mean, they have to say, "You've been chosen. You have to be at this time at this place." Turned to the left and told me that he interviewed him. It was like some very secret operation. They give you basic facts in order to get there. But I think maybe it'll be no good to know him.

DN: I agree. Well, first of all, I really like Jonathan Latham's interview of him. But it's like some people have asked me, “Would you want to interview Bob Dylan?” Or like when they do in The New York Times, this section called By the Book and they ask people, they ask famous writers, “What would be your ideal dinner party?” You pick three people. I don't think I would want to have Dylan because I want the distance. Something about admiring him at a distance feels important to me versus being at the table with him.

RF: Yeah, and in fact, he's like some sort of Moby Dick. You better not get close. You better not get too close to him. [laughter] Patti Smith, when she came to Roberto Bolaño's festival, she was invited. We had lunch with her at Ignacio Echevarría's house, who was the editor of Bolaño at the time. Of course, I started asking her about Bob Dylan, trying to know. She told me, he's a cypher. I mean, I can tell you lots of things, but they all amount to nothing. She's Patti Smith, she has some sort of proximity. I really like reading in the last biographies that he's perfectly happy playing with the grandchildren. I really like that. I think that's good. Hopeful.

DN: Yeah. Well, we have a question for you from another about style. But before we hear this question from someone else, I wanted to ask you about the question of style more generally. In one footnote in Melvill, Herman talks about how the new word imposes a new time and how he hopes it will lead to a new style. Then much later in Melvill, there is a talk of “A book (a pure style of book, a book of pure style) where many things would end so many others could begin.” You yourself talk outside your books about a conversation you had with John Banville, where you ask him which is more important, style or plot, and he answers, “Style goes on ahead giving triumphal leaps while the plot follows along behind dragging its feet.” It seems quite clear, if I ask you the same question that you asked Banville, “Which is important, style or plot?” that you too will pick style, but talk to us about style versus plot.

RF: When I had that conversation with John, with Banville, and he gave me that answer, I said to him, “Well, but maybe style can look over his shoulder and seeing blood getting behind, maybe he can come back to blood in its arms and they can walk together,” and Banville said to me, “Okay, but that's perfection. That's a really difficult thing to achieve.” But I think style is the finishing line, especially now there are more and more and more narrators but not writers. I mean people narrate basically now in books or in movies. I think that style is the place where you have to arrive. I think that when you read, there are different stages when you start reading that some sort of a video game sort of thing. But I think it applies also for a writer. I think when you start reading the first impulse when you're a kid is you identify with the protagonist, with the hero, or the anti-hero, or the bad guy, whatever. If you keep on reading, you are marveled at the idea of those characters having many books. For example, I remember when I read The Three Musketeers, and then after that I discovered that there were more books with D'Artagnan, I couldn't believe it. I was so happy. [laughter] Same with Sandokan by Emilio Salgari. You know that there was this idea of the whole fictional universe being constructed like history, like reality. If you keep on reading with a much more specialized eye, then you begin to feel a certain curiosity about the writer, about the author, about who wrote that, how he did it, how was his life, whatever. Then there's the last stage that you don't have to arrive if you're just a reader who wants to have a great time or be distracted reading a book, and that's style, when you read something and you say, “This has some very different style to this and this is really very strange compared to the things I've been reading up until now,” that's really intriguing. The idea of, I mean, you read kids' books, you read newspapers, and then you read something that could have been written just by one person and not anyone. That's strange, the idea of it has some sort of witch doctor shamanistic thing, that wise man, old wise man of the tribe, whatever, someone who has given himself the authority to tell something in a very unique way. Then you have Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Kafka, Nabokov, Proust, I mean, all the big ones, it gets even much more astonishing and strange when you think, “Okay, Ulysses by James Joyce is one day in the life of the guy. That's all.” Mrs Dalloway is one afternoon in the life of a woman. I mean, the thing that surrounds style, it's a pretty simple story. Moby Dick, same thing. Let's go after a whale, man.

DN: Yeah, and your latest book, this really brief period within the father of a famous author.

RF: Yeah.

DN: Yeah. So in the spirit of your referential and self-referential text, we have a question for you from Will Vanderhyden, the translator of your work.

RF: No, the author.

DN: The author of your latest book in English. Will has received NEA in Latin fellowships and his translation of your book, The Invented Part, won the 2018 Best Translated Book Award. I'm interviewing Will as well about translating you and about translating Melvill in particular, which will be available for supporters of the show who subscribe to the bonus audio.

RF: I really like that. It's like some sort of bonus track.

DN: Yeah, no, it is. There are a lot of long-form conversations with great translators. The Spanish language translators include Sophie Hughes talking about Fernanda Melchor, Megan McDowell talking about Alejandro Zambra and Mariana Enriquez in two separate interviews, and also Sarah Booker and Suzanne Jill Levine, both talking about different books of Cristina Rivera Garza.

RF: Suzanne Jill Levine, she wrote Manuel Puig's biography, right?

DN: It's possible.

RF: I think so, yeah.

DN: Yeah. Here's a question for you from Will.

Will Vanderhyden: Hi, Rodrigo. Even though you and I are in touch pretty regularly, I'm still very grateful for and humbled by the opportunity to ask you a question in this space. As you know, I've been working on a translation of Mantra, a novel of yours that was originally published in Spanish back in 2000, and I've also recently translated stories of yours from your first book, Historia Argentina, and your second book, Vidas de Santos. Translating fiction from earlier in your career has got me thinking about the ways in which your style has and hasn't changed over the years. To me, there's an unmistakable sensibility that's always characterized your work, and certain tendencies and impulses and stylistic ticks remain consistent throughout, but I wonder, looking back, how do you think your style has changed or evolved? Are there moments, books, stories, paragraphs, lines that mark a shift for you? I have this uninterrogated sense that something culminated in Mantra, that your style kind of broke open with and in the wake of that book. Do you think there's anything to that? Is there a before and after to Mantra for you? Either way, how has your style evolved or changed since then? Is this an impossible question to ask a writer of his or her own work? Or do you have some insight? Thanks.

RF: I think Will knows me better than myself because what he asks about Mantra is true. Everything changed there in a way, but it changed because Mantra was part of a collection of an imprint of, I think it was six, seven, or eight books. There was one by Roberto Bolaño there, where my publisher decided on the brink of the millennium to put out some sort of imprint about six, seven, or eight big, big cities and you have to write something about them. I would have chosen London or New York, but he said, “No, no way, because it's going to be very easy for you, and I don't want an easy book.” So he gave me Mexico, which I would have never chosen, but I'm married to a Mexican. That was the reason for Claudio to say, “You have to take Mexico.” I had a great time because I discovered that Mexico was very important to me. I mean, all the comic books came from Mexico, all the TV series were dubbed in Mexico. I really loved the Mummies of Guanajuato thing and the mass fighters and all that sort of thing. I was obsessed when I was a kid by Aztecs and Mayans and all the Pre-Columbian culture. But the thing was that I was like a writer for hire and they gave me this mission. I mean, when you accept something like that, you have two choices, I think. One is to say, “Okay, I'm going to do it very fast. I'm going to read the contract, going to sign it, going to get the money and run and I'm going to do it. Okay, but it's going to be like some sort of book I'm going to disown eventually and it's going to be one of those things that one does for money.” The other way of doing it is saying, “Okay, I'm going to do everything I'm afraid to do in my books here with the alibi that I was like paid for doing it. So I'm going to take all the risks. I'm going to do all the things. I don't think they're going to work out good. Things that I wouldn't, that I've never dared to do in one of my books because of fear of failure,” and it worked out and it was amazing. I did lots of things that I did after Mantra in all the books that before it and I was able to do that because I had this some sort of backstage past carte blanche get-out-of-jail card in a way and then of course, there are some huge reading experiences that form of or deformed. I told you about Dracula when I was a kid. That was one amazing thing. I really was like a fan of horror movies and Dracula movies and then I was going to read the novel and it really astonished me, the idea that the complete not abridged version of Dracula that I read, it was like 400, 500 pages. In their Dracula, it only shows up in three pages, and I found that in the movies it's different, it's all over the place all the time, but in the book, everyone is talking, writing, and thinking and being obsessed by the absence of Dracula. Dracula is at the beginning, there are some moments in the middle and at the end when he dies. It was like the first time that I was like an eight-year-old reader that wanted to be a writer, and I was already writing as an eight-year-old boy. I thought for the first time as a writer, saying, "Ah, this works like this." And then I read when I was 35, after many, many tries that they didn't work out, I finally did it. I went to a hotel for 15 days, two weeks, with the whole set of Proust In Search of Lost Time. Basically, I did that and I came transfigured after that. When I read Pale Fire by Nabokov, the same thing.

DN: Yeah.

RF: Do I answer Will's question with this?

DN: Well, in a way, it's kind of the perfect answer because you talked about your change in style through what you read, which was what we talked about at the beginning, like the figure of the reader more than the figure of the writer.

RF: Yeah, but at the same time, I consider myself very, very, very lucky because they have to reissue and I have to read proofs again of my first book, Historia Argentina, I'm already totally there. I don't have to deny that book as many writers do with the first, second, or even third, the first three books. It's all in there already.

DN: Well, given that style is most often associated with voice and often considered rightly or wrongly like a fingerprint, something intimately connected to the particulars of a person, I wanted to talk about both point of view and names and naming. I'm going to pair my question with a question from another person also. In other words, I'm going to twin two points of view on the question of point of view. You don't only play with point of view, but it also is an actual topic of meditation in this book. While Allan is walking across the ice with his vampiro, there is the question of the frozen third person versus the warm first person. The remove of the third person is seen as a way to be a good character, despite one's bad actions. This raises questions of voice in relation to identity, which you further complicate with lines like, “My father is a whale, and I am his Jonah.” But there are two places that leapt out to me as possible ways to understand your relationship to Melville and also Melville's relationship to his father. You don't explicitly connect them this way so this might actually be a stretch, but you describe wind at one point as that which, “has the shape of everything that it moves and through which it blows. Pine boughs, owl feather, and how many years has that hat been there suspended in the air?” Then another line that seems similar where you say, "And then my father squats down beside me and puts his hands on my shoulders and looks me in the eyes with his eyes full of tears." But then there's this parenthetical, “Really, it's his tears that are full of his eyes.” Both of these lines, I think, by inverting point of view, whether tears full of eyes or wind defined by everything that it blows against, they feel like they're flirting with something mysterious, but also possibly true about identity. My part of this question is to ask you to talk to us about why considerations of point of view become part of the plot of this book and the second part of this question, to elongate this to maybe even mimic one of your maximalist footnotes, the second part of the question is from Rebecca Hussey a board member of the National Book Critics Circle Award and a judge for their translation prize. She's also the co-host of a great literary podcast called One Bright Book. Here's part two of the question on voice and point of view from Rebecca.

Rebecca Hussey: Hello, David and Rodrigo. Thank you so much for inviting me to ask a question, David. One of the great pleasures of being able to do this is having the opportunity to go back and think further about Melvill, a novel that I enjoyed very much. It's a book that rewards deeper and deeper thought. My question, Rodrigo, is about voice. I'm curious how you think about the relationship of the voice or voices in the various sections of the novel and how they relate to each other. You have the third-person narration of Allan Melville's life accompanied by Herman Melville's footnotes. Then we have Allan's narration of his own story, which is told in the first and the third person, and then we have what happens with the footnotes in the main text at the beginning of the last section. It seems to me that it's possible to read the book as being about the slow emergence of a relatively stable voice that we find in that last section. It's a story about how Herman Melville became the author that he is. But also looking at the book as a whole, what stands out to me is the multi-voiced nature of the storytelling. I'm wondering how did you think about the novel's different voices and how they fit together, or don't, how they relate to each other, or don't. Thank you very much.

RF: Well, I think the book is really an education, it's the story of an education or a miseducation, whatever you want to think about it. Think about the voices, the technical things of the book, as I just told you when I felt that Dracula was something special because Dracula was not there when I read the book, I really like the idea of readers thinking about that sort of thing, but me as a writer, more of it is, I'm not going to say instinct because it won't be true, but I think it's the accumulation of all you read and all you wrote. I mean, there's some sort of sediment there, some sort of thing underground. In fact, there's one of my favorite moments in Moby Dick. I think I mentioned it in the book, it's that chapter that's called The Fountain. The fountain is the geyser or of the well that comes out, and there are like three lines in there that were suddenly Melville shows up and says, "I'm at my desk right now and this is the day and this is the hour and I'm here," and goes into the book and then goes out and you never saw him again. I like to think of myself when I'm writing a little bit like that, going in and out, but don't want it to be too involved. I don't want to interfere. I'm in control, of course. I think lots of things, but at the same time, I think that there are like two kinds of readers-writers, writers-readers. You can compare them to one who goes to see a magician. There's the audience that goes to see a magician and it's trying really hard to discover how he did it, all the time he's thinking like watching them to see if you see some string of some hidden trap door, in a way they don't want to be lied to, they want to know the truth and they don't give a damn about the illusion. There's the other kind of audience that goes to a magician that just wants to be like, “Okay, thrill me. I don't want to know how you do it. I just want to enjoy.” In that sense, when I'm writing, I'm trying to be like a reader in a way, a reader of myself of what I write of course. Of course, I can talk a lot about how the voice goes. There were some people that read Melvill and told me, I don't know, “It's amazing how you manage to mimic Melville's tone in the whole book.” Never tried to do that. Never. First of all, because I'm not worthy. I'm not going to try to channel the ghost of Herman Melville and make him speak through my fingers and my brains and my keyboard. I think that in her question, is there the real answer? I mean, she says in a way completely clearly in a theoretical way, what I clearly see in a practical way and thanks a lot to her because I heard what she found out from her lips and now I understand completely the book I wrote in a way.

DN: [Laughs] I love that, I love that. Well, there's also the theme of the importance of names in the book. In one footnote, Herman says, “I've said this before, it's been known since Homer, names and numbers and origins of men and women are as important and defining for me as the names of ships, like those of all the symbolic ships that will pass through the symbolic ship of my novel, Albatross, Rosebud, Bachelor, Delight. The names are what always tells the story.” There's some focus, starting with the cover of the book until the end of the novel, on the mysterious E that is added to Herman's name that does not exist for his father's. I wonder if this is like Robert Zimmerman becoming Bob Dylan, or as you mentioned in the afterword, William Faulkner, who also added a letter to his name, a U, and I went and looked it up. In his case, it's to distinguish himself from his father, a way to invent a self. But there are other theories that predominate, maybe more mundane and banal theories about why this E ends up in Herman's name and not in Allan's but talk to us about the E, the haunting of the E.

RF: Yeah, well, the main theory—and it seems it's the right one—is that Allan Melville's widow wanted to escape all the people that Allan Melville owed money to adding that E to the last name in order to give to her sons some sort of clear state in order for them to keep on living and starting again. The funny thing is that everyone wrote Melville with an E. I mean, all the checks and all the documents and all the things Allan Melville sang to his creditors were with an E, but of course, there's that possibility also of the idea of some sort of renewal and starting again. But it's all a mystery because I don't remember that Melville ever, ever wrote a word about his father. It was like some very shining black hole in a way and he was looking all the time like not paternal figures, but elders that happened with Nathaniel Hawthorne, his relationship with him and he was all the time looking for people who can protect him in a way.

DN: Well, I'm curious also about what seems like a long-standing interest in the three-part structure, not just The Invented Part, The Dreamed Part, The Remembered Part Trilogy, but your book Bottom of the Sky is divided into this planet, the space between this planet and the other planet, and the other planet. In this book, it’s three parts named The Father of the Son -- Glaciology; Or, the Transparency of the Ice -- The Son of the Father. It's not a coincidence, I don't think, that we keep ending up here.