Shze-Hui Tjoa : The Story Game

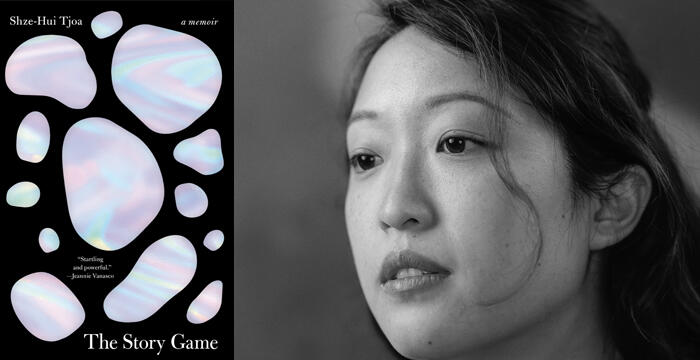

Today’s guest, Shze-Hui Tjoa, has written a book that is remarkably unique. Is it an essay collection or a memoir? A detective story or a fantasy? A journey of self-individuation or an examination of power and control? Improbably it is all of these things, and perhaps more than any of them, it is the record of a writer finding her form by breaking form, but doing so in a way that invites us into the process as it unfolds. T Kira Madden declares: “The Story Game introduces a major debut work from a most astounding talent. Shze-Hui Tjoa’s memoir not only challenges genre, it upends and splits it wide open. In meditations on grief, displacement, mental health, and family, Tjoa will have you wondering how and why we remember, and what we can’t forget. The Story Game is hypnotic, wise, and thunderously innovative. I will teach this book, I will treasure it, and I will continue to learn from its astute and hopeful insights.”

For the bonus audio, Tjoa contributes a 30-minute video reading of a favorite childhood picture book that she translates for us from Chinese to English. To learn how to subscribe to the bonus audio archive and to explore the other potential benefits of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter, head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode of Between the Covers is brought to you by All Lit Up, Canada's independent online bookstore and literary space for readers of emerging, quirky, and acclaimed indie books. All Lit Up is your Canadian connection for award-winning fiction and poetry, author interviews, book roundups, recommendations, and more. The only online retailer dedicated to Canadian literature, All Lit Up features books from 60 literary publishers and now they offer e-books in accessible formats through their e-books for Everyone collection. All Lit Up makes it easy to discover and buy exciting contemporary Canadian literature all in one place. Check out All Lit Up at www.alllitup.ca. US readers can also shop All Lit Up close to home and save on shipping when they purchase books from its bookshop.org affiliate shop. Browse selected titles at bookshop.org/shop/alllitup. Today's episode is also brought to you by Smothermoss, a much-anticipated debut novel by Alisa Alering, called “beautifully strange” by Samantha Hunt and “tense and absorbing” by Karen Joy Fowler. Smothermoss follows the story of two sisters in 1980s Appalachia. The two sisters, Sheila and Angie, could not be more different from one another. But the brutal murder of two female hikers on the Appalachian trail brings them together in what turns out to be a dangerous game of cat and mouse. At once beautiful and otherworldly, Smothermoss invites us all to more closely consider what is real and what is haunted. Smothermoss is available now from Tin House. I can confidently say that today's guest Shze-Hui Tjoa's memoir is like no other you've ever read and I say that with the highest praise. It shouldn't come as a surprise that what she has contributed for the bonus audio archive today is also like nothing else as well. For as long as it has existed, the contributions to the bonus audio archive have mostly been readings, either of a writer's own work outside of the main book discussed or writers reading other writers that they love, often with really interesting commentaries about them. Less commonly, there have been craft talks or readings that double as mini-craft talks. The archive after that has largely consisted of long-form interviews with translators when a guest comes on for a book that is either not originally in English or only partially in English. For instance, with the last episode with Cecilia Vicuña, the long-form conversation with poet and translator Daniel Borzutzky who translated her book is in the bonus audio archive. But then last year, Johanna Hedva contributed that brilliant and bonkers, and otherworldly extended sound experiment of moans and groans from various cities on book tour, mixed with various sounds recorded in space, whether of solar flares or black holes, and that mysteriously set off a mini trend of people suddenly sending in sound contributions from Canisia Lubrin to Nam Le. Similarly, very recently, Joyelle McSweeney was the first person ever in the history of the show to contribute a video, a video performance from her libretto Pistorius Rex. Lo and behold, Shze-Hui Tjoa has also contributed a video, one which obliquely deepens our main conversation about her memoir, a memoir which circles some unremembered things from her childhood and also her life then in a piano conservatory in Singapore. For the bonus audio, Shze-Hui went beyond the beyond in her gift to us. She took one of the most formative picture books from her childhood, a book that is still deeply meaningful to her as an adult, and translated it for us from Chinese to English. First, she orients us to this book, then she shares a recording of one of her friends from conservatory playing a piece of music for us to help bring us back to our childhood before she reads this translated book. Then page by page of this picture book, she narrates in English the Chinese language text written along with the incredible illustrations of Taiwanese illustrator Jimmy Liao, all of which we get to see because it's video. This is one definitely not to miss. The bonus audio is only one possible benefit one can choose from when joining the Between the Covers Community as a listener-supporter. You can find out about the many, many other things from rare collectibles to the Tin House Early Readers subscription at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Enjoy today's program with Shze-Hui Tjoa.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest, writer Shze-Hui Tjoa is from Singapore, studied literature at Oxford, and now lives in the UK. She is the non-fiction editor at Sundog Lit and her own work has been listed as notable in three successive issues of the Best American Essays 2021, 2022, and 2023. Her work has appeared everywhere from the Southeast Review to the Colorado Review to the Quarterly Literary Review Singapore. She has been granted residencies at the Vermont Studio Center and the Green Olive Arts Residency in Morocco, done writing mentorships through the AWP's Writer-to-Writer Mentorship Program and the Exposition Review, and done workshops with VONA, short for Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation, one of the only multi-genre writing workshops for writers of color, as well as at Disquiet International in Portugal and the Tin House Writers Workshop. Her essay The Story of Body was adapted to the stage, publicly rehearsed at Centre 42 in Singapore and performed at the Adelaide Fringe Festival in Australia. Shze-Hui Tjoa is here today to talk about her debut memoir The Story Game, a memoir really like no other before it. Picked as a most anticipated memoir of spring by Publishers Weekly and A Best Book of May by Book Riot, Lily Hoàng says of the book, “Shze-Hui Tjoa's The Story Game is a patient excavation of selves: not the I of today, but the version before and the one before that, flawed and flawing, all the way back to childhood, reaching through history and memory to dust free so many cruel reflections. Ardently exquisite, Shze-Hui Tjoa tenders astonishment with blushing tenacity.” The Boston Globe calls it, “A memoir that challenges the genre's definition and function.” Writers Wendy Walters and Jaquira Díaz join me in the experience of calling it “like no memoir they have ever read.” Past Between the Cover's guest Jeannie Vanasco adds, “After I read it, I felt a new world of creative possibilities opening. The Story Game is hyper-specific yet ethereal, serious and funny. It’s mesmerizing.” Finally, T Kira Madden says of this book, “The Story Game introduces a major debut work from a most astounding talent. Shze-Hui Tjoa’s memoir not only challenges genre, it upends and splits it wide open. In meditations on grief, displacement, mental health, and family, Tjoa will have you wondering how and why we remember, and what we can’t forget. The Story Game is hypnotic, wise, and thunderously innovative. I will teach this book, I will treasure it, and I will continue to learn from its astute and hopeful insights.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Shze-Hui Tjoa.

Shze-Hui Tjoa: Thank you for having me. That was a beautiful introduction.

DN: When we open the book, we encounter four or five pages of disembodied dialogue in a place called The Room, a place we return to again and again between each of these essays, and sometimes within each of these essays. But I want to delay talking about it for one moment and talk about the first essay first, the opening essay, which isn't representative of the book as a whole but that's also something that's true about all of the essays. But this first essay represents your first conception of the book, a book you didn't end up writing. It works entirely on its own terms, it isn't a draft but I think nevertheless, it represents a book project that you conceived but didn't complete. Talk to us about the book that never was, that the Island Paradise essay was supposed to be one of the anchors of.

ST: You're so right. You're right on multiple levels actually. Initially, when I started this book project, I thought I was writing a book about politics and I thought that the premise of the book would be that everywhere I looked, I kept seeing this pattern that I found really repulsive. I would see all these systems that looked very beautiful or perfect outside but inside, something was wrong. With that first essay, the Bali essay, it was about this experience I had going to Bali with my parents. My father is actually part Indonesian and he's not from Bali but we go to Bali often, and because the tourism industry there is really, really like the backbone of Bali's economy but it's also been very destructive for a lot of local people in terms of the ecological impact, particularly with the water scarcity problems that Bali faces as an island but also in terms of the wealth disparities that are generated by such a behemoth industry that is mostly catering for people from the outside who have a lot more money than the local people, so it really exacerbates all those social divides. For me, I was like, “Oh, this is a perfect example of the thing I want to talk about. I want to make it like a case study and it can fit into this book I'm writing that's all about how the whole world looks like this.” That was initially one version of the book that I was hoping to write and didn't end up writing. But you're also right in another sense, which I'm not sure if you already knew this but before I started writing any of the essays in this book actually, the very, very first thing that made me think I even wanted to write a book was that my father's family told me, “Maybe you should write a book about your grandfather's life,” and that's because my grandfather is Indonesian and he grew up in Sumatra. But when he was a young boy, there were many programs in Indonesia. I'm not sure if that's a technical word for it but it was ethnic cleansing and my grandfather is a Chinese person. So when he was a young boy, he already faced ethnic cleansing and had to run from his village together with his family, and seek refuge elsewhere. In 1965, there was a very, very large genocide of Chinese people that happened in Indonesia, like a mass killing that until today is so not very much discussed actually in Indonesia and in politics there. But that was the event that precipitated my family's move from Indonesia to Singapore. I think because of that, there was a very large part of our family's history that just got lost in time because my grandfather and grandmother don't ever talk about what happened, and they in fact never really even told their own children the reason why they left Indonesia. I think in my father's mind, there was a big part of himself that he felt he could only access if a storyteller was able to write about it and tasked me with it. He was like, “Why don't you write a book about your granddad's life?” I think that's why the very first encounter I had with this theme was around Indonesia because I just felt like there's something in this part of the world that I need to go back to and try and dig up again. But as you'll see from [inaudible] essay, that didn't happen at all. [laughter]

DN: Do you think you'll ever write this story of your grandfather? Is that something you're considering writing?

ST: I can't speak for my future selves but for me currently, I don't think I will write that because I think in a sense, I do think I have already written the book because The Story Game is that book I think in a sense. I was talking about this a little bit just now but with the first essay, I started out trying to write about my family history, then I gave up and I wrote about myself. It ended up being an essay where I said, “Actually, I don't feel a strong emotional connection to Indonesia.” I understand that there's a lot of trauma and pain tethering us to this place but I don't feel a strong connection because I only visited a few times. When I was growing up, I didn't really speak the language fluently. Maybe the part of it we kept the most was the food but apart from that, my family is very much integrated into Singapore, so I feel distant from this place and that was the final conclusion of the essay. Actually, it was only many years later. After The Story Game was published by Tin House, in fact, I think it was after The Story Games was already on the shelf, I put it on very recently, a few months ago, I suddenly realized that I think in writing the story of myself, I completed the task my father set me because that was what my grandfather wanted with his silence. He chose not to draw on his trauma because he wanted his descendants to be able to have a new story I think. He wanted us to have a better life than the life he had. He worked really hard to staunch his own wound and staunch that thing inside him that was gushing full of stories so that we could have that. I think my book is the very perfect encapsulation of his wish that came true.

DN: Oh, that's wonderful to hear. Well, if someone were to ask whether this were an essay collection or a memoir, I think the answer would be yes to both. But neither separately or together would be a sufficient description. If someone were to call it a detective story or a meta meditation on memory and narrative, and the construction of selfhood, I don't think they'd be wrong on account either. Likewise, and perhaps most pertinently to what makes this book stand out to me, if someone were to call it a fiction or even fantasy, they would also be partially correct. For me, the most mysterious thing about this book is that it is the fictional fantasy elements of the book that make the individual essays into a memoir that provide the glue or the connective tissue between the essays and somehow makes this not only not an essay collection or not a collection of things at all but a cohesive journey. So before we start that journey, I wanted to spend time with this fictional connective tissue, both what it is in its own right and how it functions to bring the book together. The book opens, as I’ve mentioned earlier, in a place called The Room, which is both a real place and an imagined space. It's populated with imagined versions of real people, a place we return to and visit many, many times in this book. Let's start with a first attempt to describe The Room. How would you describe what we encounter, The Room, its occupants, then the game that happens in it as we start the book?

ST: This is a very good question because when I was writing the book, I asked myself this question also as I was writing and maybe the murky quality of The Room is related to that because I myself as the writer didn't know what this place was. I just felt that I had a strong desire to create it. So in terms of how The Room looks, it's patterned on a bedroom that I used to share with my younger sister when we were children in our parents' old house and it has a few elements of the, I would say physicality of the room. For example, the humidity of the air in Singapore or crickets outside and also the ceiling fan that turns, and it makes a very loud whooshing sound because the air is so humid and also the smell of the room which is eucalyptus, so it has all those elements but at the same time, it's a place that's missing a lot. I think right at the beginning of the book, the narrator of the book, who is like me, says, “Yeah, I don't remember what pictures are here and I also don't remember what furniture is here.” It's a place with both presence and absence I would say, and it comes together to create enough of a vibe that the person reading the book understands, that it feels real, like a person could live there and characters could live there. But equally, there's some questions about how real is real. In terms of the people who are in The Room, one of them is a little girl and one of them is me. The little girl addresses me as her sister, so that's how the book begins, then we have a chat and she has the voice of a very young child right at the beginning where she's saying like, “Oh, it's not fun,” or like, “Put more drama in the stories,” or like, “You're lying to me,” like the kind of very emphatic things a small child would say. I think that's what I would say about The Room.

DN: Well, as we read this first political essay about Bali, we return to The Room several times before the essay ends. We do this because your sister or the figure that represents your sister is unsatisfied with your telling of it. She wants a story, not an essay. She doesn't want something scholarly or impersonal. She wants something personal and intimate. Each time we return to the essay from The Room, we return knowing that you are continuing to write in the aura of this critique. This points to an element of nonfiction that is interesting but usually not foregrounded I think. Even when we're earnestly trying to “tell the truth,” sometimes we aren't able to because of things we haven't sorted out inside of us yet. We aren't necessarily trying to deceive but what we write is still obfuscating the truth, even from the writer themselves. In the Bali essay itself, there are questions of performance and truth that are not explicitly linked to these questions for you as the memoir writer but they rhyme with the questions in a way. We learn that when the Balinese royalty commit mass suicide in 1906 in front of the invading Dutch soldiers, that the Dutch are so shamed in Europe to such an extent that they vow to preserve Balinese culture from time and from modernity, and even fake invented dances get incorporated into tradition, and become part of the real face of what Bali puts forth for the tourist. The illusion of glamor is maintained regardless of the cost to the people on the land, even if that cost is death or drought. We also learn about the popularity of cock fighting and its theatrical nature, how it also creates an illusion for the gamblers that their positions in life are mobile and fluid, even if in reality, no matter what happens in the game, their actual positions in the world are fixed and immobile. I have multiple questions I want to ask you about the fiction in this book. But first, perhaps in the most general way, what are your thoughts about fiction in relation to the real and fictional elements, and their role, whether by design or inadvertently within memoir or within nonfiction?

ST: This is such a great question. Well, I don't want to generalize but for me, certainly I feel like fiction and non-fiction feel like they're the same thing a lot of the time because as you said, for me, my experience of the world incorporates a lot of fiction and if I were to try and tell somebody what it feels like to be me, the most authentic thing to do would be to also tell them about the many fantasies I have in my head and that I'm brewing up all the time, sometimes without my own control or without consciously trying to do it. But they're always there like a parallel stream of thought that's happening in my head. I think the question you asked is so interesting because recently, I've been thinking about this. My sister actually works in reality TV.

DN: Oh, no way.

ST: Something about that is so funny to me. Maybe to use the word you just said, it rhymes. It's like a slight inversion of the thing I do. I work in non-fiction. I don't think I would ever write a book of fiction. I just don't have that inside me for some reason, the desire to make a product that's primarily fiction. I would always write non-fiction but the fictive elements are incorporated into the bigger superstructure and the superstructure is like authenticity basically. I think it's funny because maybe for my sister, it's the other way around. The container that holds everything together is fiction but there are elements of the real. Maybe it's something about the environment we came from where truth was not directly addressed and truth was always hidden, and the many layers of obfuscation creates that way of approaching the wall where the fiction, the story is a reality because the story is technically what we live through. The story that obscured the truth was our lived reality if that makes sense.

DN: Yeah, I love that. This notion of a writer maybe not “telling the truth” without knowing they're not telling the truth is really interesting in nonfiction but also even just formal decisions, like the most normative form of a memoir, which is not your memoir, of a three-act double timeline, that's a fictional form.

ST: Yeah, exactly.

DN: That's not how anybody's life happens. To put your life in a form seems also to be bringing in fake developments.

ST: I think also for me, part of it probably comes from growing up in Singapore where there was a lot of storytelling around me all the time. There was a lot of, I guess you might call it state messaging. Not that other countries don't have this but I think in Singapore, it’s very explicitly messaging from the state. [laughs] Like when you go on public transport for example, there'll be stories that are circulating around you. I've always been very aware of that, that these stories are about the reality around us. But in some way, the stories are constructed and you can see quite clearly in Singapore especially, it's very transparent, almost like you can see the bones of the story and you can see the people in the background putting elements together to decide, “Okay, this is how we're going to frame the current reality that our country is in. This is the way it comes out as a beautiful story that's easy for people to grasp and follow.” So for me, I agree completely with what you said. Even when a writer is trying to tell the truth, the act of telling is fiction. Maybe the part that involves using your voice is imaginative.

DN: Well, in The Story Game, we quickly discover that this sister figure who both asks for stories for one story after the next, she also interrogates each one, one to the next. There's a way in which this sister figure is your first reader but also almost like your editor/critic, almost like a therapist's relationship because she knows you because as a sister, she has been a witness, you have shared lived experiences, so she can comment on how you are or are not being honest with yourself as you write, what you are avoiding and more, maybe more than anyone else could. In this sense, it feels vital that this figure be your sister or an imaginative version of your sister. But it's also really clear that it's not your sister, that it's an imagined version and that you're giving words to this figure that she probably has never spoken. I believe it was your editor at Tin House, Elizabeth DeMeo, who called this book speculative nonfiction, which I really like. This imagined sister feels like it's at the core of this element of the book. There's always, in any writing, a gap between a represented person on the page and the actual person in the world. But I think that gap in your book is really accentuated, which both calls attention to the artifice of any representation through an exaggerated sense of artifice in your book but also actually not trying to capture your sister on the page at all, even as it's important that it “remain her.” In a way, it feels like your sister is in the end another aspect of you. But talk to us about the parameters—given that she is a real person working in reality TV—talk to us about the parameters of what, if there are parameters, you would allow for yourself and how you portray your sister, how far you're willing to travel from what she would actually say or do as you portray your sister in The Room.

ST: I feel like the only part of the book where my sister is actually herself—there's a slight overlap between the sister in the book and the sister in the world—is maybe in the very last page of the book where I have a phone call with my sister in the real world. You have no idea how many times I edited those pages. [laughs] I edited them so much. In fact, I think the very last edit that I gave Elizabeth, my editor, before the book went to print was to tell her to change a word in that sentence when I'm describing the quality of my sister's voice. I said, “Okay, this is not the right word. It's close but it's not exactly right.” I need it to be exactly right because this is the part where she's a real person. I think that I have a lot of respect for other people's sense of self. I just always have had this, particularly when it's someone who's close to me, like with my sister, I find it almost impossible to tell a lie about what the person said or I feel very, very uncomfortable speaking on behalf of the other person. I would maybe transcribe their words directly if they gave them to me. But then again, I feel like even so, there is a power dynamic that appears because my name is on the book and they end up being a character in the book, whereas a more accurate kind of literary form which maybe has yet to be imagined would call us co-creators. A memoir is a co-creator with every single other human being who appears in the pages as a character. I feel like for me, it just feels like a place I can't really go. But equally, I love what you said. It's very clear that this is not my sister because I think that the person who appears in the book is what I wish my sister was. It's like all the elements of wishfulness about the relationship that we never had, like we never got to have this relationship because our relationship was one of silence for many years, so there's so much love that was lost over the years. I think that for me, I always have this question about when does this stuff go. [laughs] It's funny because I mean just to go on a tangent a little bit, I recently was at a reading for another writer. I think it's Rachel Khong, then she was talking about how for her, she feels like fiction is a way of exploring that. She's like, “Because there are so many unlived realities in your life, it's like every time you choose a path, a thousand other paths disappear, like an unnameable number of paths disappear. You cannot count them, uncountable.” Then she's like, “Okay, so all that stuff needs to go somewhere.” For her, she puts it in fiction. I think I have that same heart actually, I have that same emotional drive, like I need to preserve everything. I'm like a hoarder when it comes to emotions, experiences, or abstract qualities and I have to keep everything. It has to go in the book. But really for me, it goes into nonfiction because it's such a shame to give up on all that love or the love that I could have imagined existing between us. I don't want it to disappear. I want people to know that this is what I wish we had.

DN: Well, before we leave the notion of the relationship of representation to the real, one thing we learn in the book is that you have a memory gap in your childhood where you can't remember many of the years leading up to a major scoliosis surgery you had in your teens. You could say this is one of the sources of suspense in the book. One of the ways the book feels like a detective memoir or a psychological excavation where we and you don't know what we're going to find as your sister pushes you more toward authenticity on the page one essay to the next. But one thing that jumped out to me in one of your interviews for this book is that when you attended a theatrical performance of your essay The Story of Body, that it was only seeing yourself being performed by another on stage in a specific scene that made you realize the gravity of what you had been through in real life. That the theatrical performance had made your own life more real to you. I just wanted to hopefully give you a moment to talk about that experience a little bit.

ST: Yeah, that's another one of those things where somehow, the fiction is realer than the real life experience. My friend who performed that scene Shien Hiam, one of the choices he made was because I have a number of titanium screws in my bed and I was unconscious while the screws were being put into me, so I didn't experience it. It's almost like time folded in on itself. I was lying there on the operating table, then the next moment, I was awake and life went back to normal. Nothing has happened. It's almost like a chunk of time was bitten out of my life. I think that with Shien Hiam's performance, in theater, you're using your body, so the body lives in time, lives in chronological ordinary time and he decided for every single one of the screws that went into my spine, he would make a sound. Because it became translated into this oral thing that I could hear, I felt like I really understood how my time went into fixing my spine. He was already shortening it. I'm sure this surgery was a really, really long surgery, an entire day for this surgeon. Something about feeling the breath and the weight of time, I think it brought a new kind of grief that up to that point I had somehow kept for myself because when I'm writing a book, things can happen so fast. You can move from one year to the next year from sentence to sentence. Time is just like a thing you play with. It's something you chuckle, then you put it down, then you move on to something else. But for people who are working with their bodies, time is like the limiting factor. The biggest enemy of the body is time. [laughs] Time is the thing that makes you die in the end. I think as a writer, sometimes I forget about the reality of time because I'm the master of time when I'm writing. I think working with that person, Shien Hiam, was a really special experience for me. I feel like almost he had a point of view of my life that I was not able to have and because of the closeness of his own relationship with his body, I could access something that for my own self-protection, I had hidden away from myself.

DN: Well, there are actual fictional influences to this book you've mentioned also. You've mentioned the book Piranesi by Susanna Clarke.

ST: I love that book.

DN: And also that at one point, you binged on both Agatha Christie books and TV adaptations. How would you speak to the influences of these other fictional books on this non-fictional book?

ST: With Piranesi, the thing that I love about Piranesi is the world building element. So for anyone who's not read the book, I'll give a very quick summary. It's just about a man who lives in a giant house. It's a huge house and he wanders around from room to room, and there are lots of statues in the house but there are also tidal waves, there are flocks of birds. It's a house that basically stands in for the entire world. This man is like a very innocent man and he just wanders around, and he praises the house because it is his world, it's his god. He believes the house created him and he gives a lot of respect to the house, and he venerates the house basically. But one day, a little bit of doubt is cast into this worldview because there's another man in the house and the man calls him this name Piranesi. The character is like, “I just feel like this is not my name.” He just has an implicit feeling that this is wrong. I love that because I think Susanna Clarke is actually telling a very universal experience of what it feels like to be lonely and also what it feels like to not know who you are, to live in a world of somebody else's making, yet to believe that that is your world, do not have a grasp on what is yours and what is the others, and what has been given to you, I think that this is such a universal and also complex idea. I think you could write a thousand books about this but instead she built a whole world rather than dissect the idea. She built something creative and a new thing to represent this idea. She built a house and I love that. I think for me, that's something that happens in fiction that has always drawn me to fiction. You can see I was talking about the advertisement on the public transport in Singapore as the exact same thing. You see someone with a hammer and a nail, and you see them building. They're building a wall. [laughter] That's so intriguing to me. I love to see that purpose. It makes me feel like I'm living when I watch people do that. For the detective stories, I think what I needed was comfort. What I got from those stories was comfort. I used to read them also when I was a child actually. I read all of it. I [inaudible] book when I was a child, I think because there's so much comfort built into the promise that somebody knows where the story is going. Even if it takes a lot of dark turns, you know that a detective will almost always solve a mystery and the very last moment, the right clue will land on his lap, and the detective will light up, and he'll be like, “Oh, I know who did it.” [laughter] I feel like when I was working on The Story Game, I didn't have this feeling because I was venturing out into the unknown. Especially in the dialogue section, I really didn't know if it was for anything. Also, as I said before, I didn't know who the characters were. I didn't know who the little girl was and because of that, I just needed to have this feeling of, “Okay, somebody knows what's going to happen. I had to believe that I could be like Agatha Christie. If the thing inside me that created the beginning was the same thing that would end the book, then I have to trust that it knows where it's going.

DN: Well, with the second essay, your Best American Essays’ notable essay on being in love with a white man, we already see a little bit of shift in how you write an essay. It's still intellectual, political, and exterior in some ways but it is also about meeting your future husband. We get your anxiety about whether you can even now talk about decoloniality or be on the right side of history if you're married to a white man and also choosing to live in Europe, about how you, meeting Thomas, sort of mimicked the feminized Singapore meeting Sir Stamford Raffles, the man who founded the Port City and its modern incarnation. We're with you as you explore this gap between what you know you should want and what you actually want. I was hoping maybe before we talk a little bit about this essay, if we could hear a little bit from it.

ST: Yeah, sure.

DN: What I was thinking was 42 to 44.

ST: Okay. Nobody's ever asked for this section but actually, a lot of Singaporean people have told me this is their favorite section.

DN: Oh, really? Okay, great.

ST: Okay, I will read it. Okay.

DN: We've been listening to Shze-Hui Tjoa read from The Story Game. So, pretty early in the book, having only encountered the first several essays and been into The Room now many times within and between them, we not only understand that there's a memory gap, a place where your character can't go within themselves that your sister is pushing you toward but also that there are ways you have learned to present yourself that aren't true. I even wonder if some of these ways you present yourself that are false might be part of the mechanism of preserving the memorylessness space. But either way, your sister calls bullshit on the second essay, [laughter] an essay that is quite nuanced about questions of race and nationality, and about the ways theory and embodied desire can be at cross purposes but also one that completely misrepresents your marriage, which we learn in The Room is actually in disarray, something we would never guess from the essay. Similarly in the third story, we get Singapore as a place you love to be from and to return to but later in The Room, we learned that in reality, you hated it, that it felt soul-destroying, authoritarian, hyper-capitalist, anti-queer, and more. We discover we're with an unreliable narrator but one who is unreliable to herself ultimately, yet one who also has this room of accountability. So we have absences where language can't yet be formed by the person speaking and we have someone also at odds with how they use language with regards to what they know about themselves. You've linked some of this explicitly to trauma but also some of it to cultural forces and how these both intersect. In the book, you talk about how school began at sunrise and went to 10:00 PM. That at age nine, children would be sorted into gifted, express, or normal. You've written outside of the book about how, at piano conservatory, they would physically and verbally coerce you by placing thumb tacks on the piano keys to punish you when wrong notes were played. In your interview with Claire Chee at Electric Literature, you talk about how being shunted into the gifted track in school very early made you want to live up to the label that was given to you rather than to figure out what you would want to authentically be on your own terms. You've also talked outside the book about how communitarian Singapore is something you've alluded to today already, that lots of the messaging is through the “we” pronoun, unlike the pledge of allegiance here that begins with the word “I,” the pledge in Singapore begins with “we” and it was from this place that you started from in figuring out who you were, a structure that the book mimics insofar as the essays start very exterior and become less so. Talk to us more about how you see either the culture of Singapore generally or its educational approach, more specifically becoming an element of the difficulty of presenting yourself failing or presenting yourself unhappy on the page.

ST: That's such a great question. Especially now, so many years after leaving home, I moved to the UK 12 years ago now. I feel like I'm not the best person to tell you about what life is like anymore. There are people who can do it much better than me, so I guess I'm a bit wary about speaking about what it's like now. But for me, in terms of the education system, yeah, it had a very strong impact on me and I didn't even realize for many years, there was a kind of nationalized system that assumed that all people have the same kind of intelligence. That's the first thing. It assumes that there is one kind of intelligence and it's the kind of intelligence that can be captured on a piece of paper. Then also, it makes a further jump, which is to say that well, the level of this kind of intelligence you have will determine the role you play in society for the rest of your life, which I think is a really terrifying message, not only for anybody to hear but for a nine-year-old to hear because it feels like everything you do rides on this one piece of paper that you're holding. I mentioned that particular streaming exam because I think it's the most unusual example for an outsider to hear. But this dynamic was something that was repeated constantly in my childhood. There were always more and more pieces of paper that you had to get to prove your worthiness, to rise up through the ranks and get a powerful position in society to put it very quickly. I think that for me, for many, many years, this actually prevented me from understanding how my own form of intelligence works. Actually, I had to go through, as you said, I study in Oxford, I also study in Cambridge actually, which is not something I usually tell people. But the reason why I don't usually tell people is because I think that going through those two academic institutions, the main thing it showed me was actually that the kind of intelligence I possess is not really like academic intelligence. Actually, it's not the kind of intelligence that I was streamed for and that I was set to possess by the state when I was young. I think I actually have a lot of intelligence from doing things and you see that in The Story Game too because I am living the book in real time while writing it. I have to live things to really understand them. I have to do them with my hands, I mean I was a pianist, so it checks out. I have to live it with my body, then I grasp the essence of the thing but I'm not good with facts. I'm not good with recounts. I feel like The Story Game is so interesting because writing a book, I am playing into this tradition of academic excellence, which I took many years to extract myself from, but I guess that The Story Game, some people on Goodreads have said this, they said like, “It's not really a book. It's not a memoir for people who usually like memoirs,” or they're like, “Yeah, I don't usually like reading. I don't usually like books but I like this book.” [laughs] Whenever I hear that, I feel like that's such a compliment because that feels authentic to my own experience of writing this book. I thought I was writing a really dense academic thing that would be like the final stamp of approval. That's like, “Yes, you made it. You are what you were promised that you would be and you have achieved your potential.” But it turned out to be a completely different thing. I realized that the standards I was trying to live up to were not standards that I liked and they're not standards that make me happy ultimately. I'm much more comfortable finding my way through real life experience. [laughs] I think the book is a book that breaks the boundary between the text and life in that way because of this.

DN: You wrote this very moving essay outside of the book about your experience doing the AWP's Writer-to-Writer Mentorship Program, a mentorship you had under the writer Lily Hoang where she was really amazing at sensing when receiving feedback from her could be potentially overwhelming or derail the writing process. At one point, she tells you, witnessing your demeanor and facial expression, that you should just hold on to the feedback, not look at it and keep writing. Her flexibility, her listening to and for your response to her, the bi-directional nature of it where it was the opposite of a top-down approach seemed to me as if it were revelatory to you. There are qualities of how you describe Lily in the sister character too, as well as, as I mentioned earlier, qualities of a therapist in the sister figure where the critique of your work isn't based on an external system but rather from your own relationship to yourself. In fact, you start to see a therapist part way through the book as well. One way I think you could view this book is as your journey toward not just an individuation from your family of origin and culture of origin but a journey toward becoming a writer. I wondered if that felt right to you, if you felt like one way you could frame the journey we take with you is the journey of becoming a writer.

ST: Yeah, I think you're totally right. It also makes me think of your previous question and what we spoke about there because I feel that when I started the book, I had a very clear received notion of what it means to be a writer and to be a person who has written a book. I thought that it means certain kinds of ways of perceiving the world. It means a certain relationship to other people, to the public, like my readers for example. Actually, when I finished writing the book, I became a writer but I became a writer on my own terms. I was like, “This is the reason why I write,” and it's not for the things that people told me I should get. Maybe one very clear example of that in my own life is like my relationship to prestige. When I started writing the book, and I think you can see this in the tone of the essays or so, I believe that I was doing it to gain prestige. I thought that was the most important thing. In fact, when I was sending out those essays after I wrote them, I would send them to the most prestigious places I could imagine, like New York Times, send it to all these places that in fact, like the telltale sign is I don't read a lot of these things but I feel like I just do it because this is what a writer would do. [laughter] I think as the book progressed and my own writing journey progressed, so my relationship with prestige changed completely because I realized, like for me, the reason why I wanted prestige was because I wanted to be in connection with other people who would accept me and see me for who I was, and actually like you don't need prestige to get there. [laughs] Prestige is not a door you necessarily have to walk through to find connection. You can find connection just by being like [inaudible] actually. By the end of the book, I was submitting to different places. My vision of what it meant to live a happy literary life totally changed. So I don't know if that really answers your question. But I do think my feeling of what it means to be a writer has changed very, very dramatically over the past five years.

DN: Well, in your conversation with your editor, Elizabeth, she talked about how many writers approach her regarding how useful this book is to them as writers and I can see why. I wanted to read a couple of things you said on your blog in this light. These are things you wrote before you had a book deal, “I've written on here before that for me, the temptation has always been to erase the past from my own artistic record and present myself like a person who has always been fully formed instead of as someone who has had to grow over many years, and discover what works doesn't work for them.” Then speaking about writing The Story of Body, an essay that comes late in this collection, you say, “This essay has made me reconsider what I'm doing with my whole book project. Once ‘The Story of Body’ arrived on the page, I knew with 100% certainty that this was what I wanted to be writing about - this topic, this part of myself. Which made me wonder if the other essays - which I had previously thought might be coming together to make a book - were really nothing more than practice pieces... rote exercises in shoring up history in language. This isn't a question that I've fully resolved yet! I wonder if there isn't some value, after all, in sharing practice pieces with the world - something in it that has to do with being real and vulnerable and human.” But what I think is great about The Story Game, contrary to your fear, is that each piece does feel complete. It doesn't feel like you're sharing drafts or incomplete pieces but you are sharing drafts of yourself. Perhaps with this essay, this essay The Story of Body, you feel an arrival to something more fundamentally you. But either way, it feels super generous that we get to travel with you practicing you. I assume this journey across essays was something that you created through careful ordering and reordering, and construction through that ordering, so I was really amazed to discover that the essays appear in the book in the order that they were written. I was likewise blown away that the last thing you wrote was the room dialogue scenes, the aspect of the book that is most essential to it and the only way I could imagine it working together as a collection was the actual element you didn't have until the very end, then you took nearly a year to figure out how to do it and in what way. Talk to us about the construction of the book as a book, maybe about the book before The Room existed and how it arrives at its final form over time.

ST: First of all, thank you for reading from my blog. I feel like that's very moving for me because I feel like the writing I do on my blog is not lesser than the writing I do in a published book. It's the same for us. It's me. [laughs] Yeah, it's very moving actually to hear you read from that, to treat it with equal respect as the words on the printed page, so thank you. The book was written in the exact same order as it appears, maybe that also was taking a risk, exposing something that could be vulnerable to people because you're not the person to say this and maybe I don't really understand actually because everybody is always very surprised by this. But to me it feels like the book could not work if I reordered the essay. The very chronology of the essays and the order in which they appear is me. That was the journey I went through because I'm basically showing the reader different versions of myself and getting that ordering correct is important because I'm showing you the journey of growth I went through, and the way I changed from essay to essay. As you yourself mentioned earlier in between the first and second essay, you can see the way already I'm tailoring my sense of self based on my self-reflection. AFter the first essay, I'm like, “Okay, I realized I was too academic there, so I need to include more details of my life.” Then after that second essay, I'm like, “Well, I did include a lot of details from my life but they were very dishonest and they didn't include the ugly thing. So the third essay is going to be very ugly. It's going to be about depression.” You can literally see the thought process of the person moving from draft to draft of themselves. So in terms of how the book came together, it was literally written that way, essay by essay, and as the blog said, when I got to The Story of Body, I was like, “Oh, man, I think this is it.” [laughs] The other essays were just attempts to get here and this is the place where the book actually has a form, and actually, it contains something that's true about me. But then after that essay, I had a very strong feeling that I needed to write something about my sister and I tried really, really hard to write that essay. But equally when I was trying to construct this essay, I felt like the essay form was not the right container for whatever I had to say about my sister because no matter how much I tried to talk about her, I realized that it was impossible for me to know what she was thinking. Our relationship when we were growing up was so heavily skewed in terms of its control dynamics towards me. I had so much control and she was so much lacking in agency, I think when we spent time together, I always knew what I wanted her to do in every interaction that I could recall, but I had no idea how she responded. My brain had just blocked that out because in some way, I guess it saw her like a doll rather than a human being and it was not possible to write about her. I remember actually when I was going through this process, it took eight months, this pain-staking process of writing and writing and trying to write about my sister, I actually had experienced a very, I would say intuitive moment of grief. One day I just broke down and I cried and I had therapy that day and I told my therapist, I was like, “I feel like in writing this essay, I'm destroying myself because I'm destroying the act of storytelling. This essay is going to be the end of all stories for me.”

DN: Wow.

ST: Yeah, I mean, I'm very dramatic. I'm very dramatic. [laughter] I was like, “This is the end, no more stories.” [inaudible] Of course, she didn't say that. She was like, "Okay, that's interesting." [laughter] But I feel like I sensed even before I got there, maybe, that there's no essay which contains a story structure. It's like there's some stakes and then there's some suspense and then there's a big event that resolves it and then I learn something and then I change. I become a new person. That was not going to work for what I now needed to do; it was to include the subjectivity of another human being. Maybe it worked for some other writers, but for me, I just knew that what I think of as a story was actually an obstacle rather than a help in terms of describing my life and my relationship with this person who I love. Yeah, it was very sad for me because I think I am quite good at telling stories. In the previous essays, I enjoy that process. I enjoy creating a story and I don't think a lot of my identity derives from my ability to do this and practice this skill. But that was what I needed to grow. That's what I needed to grow is to try something that doesn't have a 100% success rate guaranteed. Then that was what I think processing that feeling of like, “Oh, the stories are disappearing, no more stories in my world,” was what enabled me to write the dialogue. I don't think the dialogue represents the end of stories actually.

DN: You've talked elsewhere about how before you found your agent, who as an aside, I think is another person who seems to have some of the qualities of your sister character in your book, a person who was able to sense emotions in you that were too subtextual on the page and push you to draw them forward, before you found this agent, you had a different agent reach out to you who was curious if you had a book, and when she saw your manuscript was interested if you would remove the experimental elements in it, the room elements in it. It was actually interested potentially in the essays as an essay collection. I wondered if you could talk for a moment about that encounter and the series of decisions to walk away from one agent and look for another.

ST: She reached out to me at a time when I was already seeking beta reader feedback on the manuscript and she had read one of the essays in the collection which was called The True Wonders of the Holy Land and she really liked that essay. I think she was hoping that I would produce for her a stack of essays that all sounded similar and tone to that. I would say it's a particularly chatty essay. It's a particularly like funny essay with a lot of human character. It's a lot of funny characters in the essay. I think she was drawn to that. But I didn't have that to show her. I actually only had this manuscript. I gave her my hat. I think she she gave me a piece of mixed feedback actually where she said that she really enjoyed the book like she read it really quickly, she read it in one night, and she liked it but she doesn't think she can sell it. I think for me, when I received that piece of feedback, because she wanted me to try and rewrite the book, I felt like first of all I don't have it in me. I don't have it in me because this thing took five years and as I said, I was so careful even with the ordering of the essays. I think for me, it feels like the thing I'm showing you is the evidence of my life and I can't really redo that. This is actually how it happened because the book is documenting the process of writing. I can't tell you a lie about how the book came to be. I just wasn't really interested in that. But at the same time, Allison, my agent, had also made me an offer and I felt that Allison saw the book very clearly for what it was. She liked the dialogue. She said that that was a thing that drew her to the book was that it felt like each essay was digging deeper and deeper. So I felt we were a good fit because the dialogue is maybe like, you know how people always say like when you're looking for new relationships, you should leave with a rough edge of yourself. [laughs] Maybe not people always say, but I have heard it being said. I think the dialogue is the rough edge of me in the book. It felt very important that whoever I worked with was able to not only tolerate that, but enjoy it and see the benefit of that.

DN: Well, before I knew that you had read Jeannie Vanasco, before I knew that Jeannie Vanasco had read you, that she has placed you permanently on her teaching syllabus, before I knew that you two would be doing various events around this book together, back when I thought of you both entirely separate from each other, it was her book, the one that she came on the show for, Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl, that I thought of while reading The Story Game. Not because they're similar reads, I don't think they are, but because easily, they're the two memoirs that first come to mind in terms of how formally innovative they are and the degree of risk that they both take, formally, but also personally. Marta Bausells for Lit Hub said of Jeannie's book, “It’s nuanced, profound, murky, morally complex, truly uncomfortable, infuriating—I am so sorry, I need to call it brave. . . . I’m still out of breath, processing, needing to discuss it—so please, everyone hurry up and read it.” Your, her approach, mode of being within the two books are very different. But one thing both books share is that, as you've already mentioned today, the questions of the book's construction are very much part of the book itself; questions of how to make the book are asked and deliberated over within the narratives of both books. When I discovered that she was a huge champion of yours and that you were going to be in conversation with her as part of your tour, she became my undercover spy with your blessing. [laughter] She went to your conversation with Elizabeth DeMeo and she recorded it on her phone, including a dog having a protracted hacking fit very close to the phone's microphone at one point. You two also had an off the record Zoom interview as part of your development of your upcoming conversation for BOMB Magazine, of which I was given access to, and much more. So really a ton of the intel about today is thanks to Jeannie. Here's a question for you from Jeannie Vanasco about another mystery in the book beyond the memory gap, the many years when your sister in real life stopped speaking to you without explanation.

Jeannie Vanasco: Hi, Shze-Hui and hi, David. Thank you so much for letting me be a part of this conversation. So I keep thinking about the moment in The Story Game when Hui tells her sister, “The truth is that whenever I looked at you, Nin, there was a part of me that thought I am bad, I hate myself, I shouldn't exist. But because it was impossible to hold onto those thoughts for very long, I wished that you were gone instead.” “I shouldn't exist and I wished that you were gone instead,” our common thoughts among victims of the silent treatment, especially when a loved one inflicts a lengthy silence and the silence goes unexplained. As you know, I'm writing a book about my experiences with my mom's silent treatments, which is why I'm so curious to hear you talk about the silent treatment’s influence on your writing process. What I find so interesting in your case is that your sister's silence started years before you pursued writing, so I'm also wondering if you have any sense of how her silence may have shaped you as a writer. Thank you again, both of you, and I look forward to your answer, Shze-Hui.

ST: Well, first of all, I'm so happy that Jeannie asked the question because, yeah, she's been such a huge supporter of the book, and I love her books so much, I think that not only we're similar in the way you describe in terms of like playing with form and the bravery to try new forms, but also from having worked with her a bit on book tour and also just from being a reader of her book, I think that this kind of respect for the other and the other subjectivity is something that's really present in Jeannie's work. That's always been something I really really admired because I think it's a very interesting question to play with as a memoirist. What can you do to write about another person when you recognize that they are exactly as real as you are? That second book you mentioned, Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl, I think she is exploring that question in such a powerful way and for me it was so generative to read that book.

DN: Me too.

ST: So thank you for asking Jeannie on this show. In terms of how my sister's silence shaped me as a writer, I think the funny thing is until I spoke to Jeannie for that interview you referenced for a BOMB Magazine interview, I had never thought of what my sister did to me as the silent treatment. I had never really applied a label in the way she treated me, maybe because there was an inability to acknowledge it for me. I preferred to live in my fantasy where I was like, “This person really loves me, so somehow this silence must be a manifestation of that love.” The only way I could make that make sense to me was to think that maybe the silence was a game, hence The Story Game. Yeah, because I was like, “I can't believe that this person doesn't like me because we've grown up together, so this must be some kind of fun game that they have created for me play. And maybe if I find the exact right thing to say to her or I move in the exact right way or I crack the code somehow, like a detective, I crack the code and I find the key, then the silence will end.” I could only perceive it as like a fun exciting thing because I guess my head couldn't hold a reality that we are not that close. I think that that's actually maybe the way in which the silence most profoundly affected the way I write. It affected this kind of dynamic in the book where it's like two people dwelling. I think in one of the reviews that I read for The Story Game, somebody said that my sister is a worthy adversary and that's exactly how I felt about her silence. I felt like she created this horrific game and I must win because she's a worthy opponent. [laughter] Maybe something about that gave me some creative or generative energy, because if it's a game, then there's nothing to lose. You can keep playing because you believe that deep down inside, the person loves you.

DN: Thinking both about your sister's silence toward you over the years while living under the same roof and you creating an imagined version of her, but also how much we learned about your husband Thomas and your marriage, and perhaps most so about your parents, I wanted to ask you how you did or didn't involve them in the making of the book or in preparation for the book's arrival. When you talked with Claire Chee, who I presume is from Singapore too, when she says, “Singapore adopts a paternalistic approach to governance that, compounded with common Asian dynamics of filial piety, has produced a general cultural aversion to questioning one’s elders. In the book, you have to reckon with how your parents—who you assert are good people—could hurt you so terribly,” your answer that being a good child meant that one had to, in order to respect one's elders, deny the parts of yourself that remember all the ways they were made to feel small, angry, or afraid, and you ask, "What kind of love is this—that wilfully denies the fullness of what we can remember about another person?" Lastly, in a podcast conversation that I particularly loved, a podcast called Writing Stories, you talk about how originally, you worried about whether the stories would find readers. But now that you are on tour, you were no longer worried about readership or connection. You were with your readers, you were finding connection, but instead, you were worried about how family and people from your childhood would potentially react to the book. In anticipation of loss or rupture, you reminded yourself of the new connections that were being made. You mentioned in that podcast that your parents were coming to an event at an upcoming reading on your tour, which by now has already happened, and I get the impression that you don't say this explicitly, that they hadn't engaged with the book much before this. But what conversations did you or didn't you have with any of these people who are close in your life and who become portrayed in a personal way because you're revealing personal things about yourself in your own process? How much or how little were you willing to show them in advance of publication? If you're open to it, how has it gone in the end with family and friends, now that the book is out in the world?

ST: I read this book last night. It's called The Words That Remain by Stênio Gardel. It's a book that my friend, David Martinez, who's also a memoirist, recommended it to me because he was actually my first conversation partner at the event. Before my parents were involved, not the event my parents went to, but the only event preceding that, we were talking about our parents' various reactions to our book. It's actually not true that both my parents haven't engaged. My mom has engaged very deeply with the entire book. In fact, very, very quickly, she read everything and produced a response instantaneously. But my dad has not read the book. I think because of what I was sharing, that this book, in some way, it's my attempt to write about him and about our family connection through that particular side of my lineage, I think it was very painful to me that he would not actually read the entire book and so my friend David who I think went through something similar recommended this book to me, which is a great story. I cried continuously while reading this book. It's a story about how there are two men and they're in a relationship but they get separated because of prejudice against gay relationships in Brazil and then one of them writes a letter to the other one and the other person doesn't read it. So he just carries this letter for his whole life until he's an old man. He doesn't read it because he's illiterate and he like visits learning to read so that he never has a reason to open this letter. Throughout the entire book, and the book is a story about him going on this journey to learn to read, he goes to night class and he slowly picks up the skills and processes what happened enough to generate the bravery to open the letter and throughout the entire book, you're kept on tenterhooks because I was very curious as a reader like what this letter says, what is in this letter because this man has lived for decades not knowing, just keeping the material physicality of the letter on his body and that's his reminder of the past. I don't want to give a spoiler but I think suffice to say that that's not very important at the end. The actual contents of the letter are not so important as much as the gesture of reading it. I think that something about this story reminds me of my feelings about my father not reading the book because at the beginning, I think I really wanted a certain response from him. Especially with him coming to my LA event, he might not read the book but he brought his body there. The Story Game is a book about going from the mind to the body, understanding that actually the body is also an equal and equally legitimate side of expression and of self-hood. I think something about just his physical presence there, because he doesn't live in LA, he flew all the way from Singapore to LA not only for this event but he showed up at this event, I think something about that, accepting that that is enough, for me, it's like my equivalent of opening the letter. I think for me, maybe he has been trying to give me something all my life that, because I live so much in my own head and not in my body, I was not able to receive this gift, I had to write The Story Game to go back into my body and be like, “Your presence is enough. Thank you for coming to the event.” But there was a lot of grief involved in this journey.

DN: Yeah, no, that's beautiful reframing though, imagining the presence of his body, of him supporting you outside of language.

ST: Yes, exactly. I think maybe also because of my background, I wouldn't say I'm a lot more highly educated than my parents. They also went to university. But in terms of the leap between the generations, a lot of people in Singapore, their grandparents might be illiterate, for example, and I went to a very prestigious university overseas. I think there is an extent to which the older generations might not be able to understand the medium of connection that is most easy for me or most intuitive for me personally, and something about just making peace with that is a way of accepting them for who they are.

DN: Yeah. Well, I want to preserve both the mystery around the memory loss and the mystery around your sister's silent treatment for the reader, but I do think what makes this book richer is that it isn't just the discovery of oneself as a victim, but take some more sophisticated look at what victims of trauma do with trauma, which not uncommonly is to reproduce it. There are ways you reproduce the authoritarian environment that you are susceptible to in the book. For instance, in one great essay about going to volunteer at an eco lodge in the Baltics, only to find yourself in an exploitative authoritarian scam where the work you do not only wasn't particularly ecological, it was mainly funding the owner's vacations. Or to a lesser extent, you're volunteering at a Palestinian convent in East Jerusalem where your Palestinian co-workers were mystified why you would fly across the world to wash other people's dishes for free. But in ways that I won't go into here, the book also explores the way victims can be victimizers, the way victims can continue a chain of victimization. Instead of talking about it in the book, I wanted to talk about some of what you've written about Palestine outside of the book. You've been very outspoken on social media on behalf of Palestine and you've written on your blog about your anguish regarding the eight months of dehumanization, dispossession, and indiscriminate destruction and death that has been unleashed on an already confined civilian population since October 7th. Back in late November, you say that something had died in you, watching Israel and Western governments genocide of the in people unfolding in real time, that you were so shaken that you couldn't shut up, and you say at the end of that blog post six months ago, "I will probably feel it until the day I die, and it will probably live inside every piece of art or writing that I make from now on." Before I bring this back to the project of your book, let's start exterior, as your book does, for instance, where you talk in your blog about the grief you felt for a political system you thought you lived in, but now realized for certain that you had never lived in, not for one second of your life, and where you talk about how the prevailing notion and ideology in Singapore, the one that you were raised under, was that leaders by definition were benevolent and competent. You've co-written an article with Ameera Aslam about some slides from Singapore's Ministry of Education that were meant to teach students about Gaza and about the uproar and controversy that these slides caused. I wanted to make a space for you to speak about Palestine, but also perhaps share with us about the particular situation of Singapore in relation to Palestine too.

ST: Yeah, this is another difficult one where I feel like I want to answer it in a way where I don't speak on behalf of everyone, everyone from the industry, because there are many, many people and actually people have very different views on this. So I think there are a lot of parts of a question. One of them is the grief I feel which actually for me, the most interesting question arguably of the past nine months is why is it that this grief and anger at seeing the sites that I have seen, and I would say many people on earth have seen, why is it that this thing which my body instinctively does when seeing these horrific sites, like I've seen a person's legs get shredded, I've seen really horrible things, why is it that somehow that instinctive feeling does not translate into the level of politics and into the level of collective action? I think for me, this is the question that not only profoundly disturbs me, but also energizes me. Maybe that's what I meant when I said that I think it will be there always in my writing. The level of dehumanization that I see happening in the media at the moment, I think there is a way in which I understand from having written The Story Game is not really possible to dehumanize another person to that extent unless in some way, you also believe that you are not human. In some way, it's not very easy to dehumanize another person if you yourself are dehumanized because in as much as you recognize your own experience of selfhood, you are able to afford that grace to another person and you're able to recognize that they probably feel that same way about themselves. I think for me, that is actually the saddest and most troubling thing because I've realized that many, many people around me, not only in this industry but also just socially and also many of my friends who are in this government you mentioned, the Singapore government, which has done a lot actually to repress people who want to speak out or who just want to voice how unhappy or how shaken they are, even that voicing is something that's seen as a threat to security and must be stamped out. Perhaps unless somebody who is not from a social position would find it very easy to criticize, like all government officials are just like heartless people who only care about efficacy and about material concerns of security and they have no heart, but I cannot say that because these are people I went to school with. These are the children who were streamed with me at age nine into the stream. I remember what they were like when we were 10 years old, 11 years old. [laughs] I remember that we used to play games, and I remember their feelings. I remember they are ashamed when the teacher on them and they don't answer correctly or I remember their first crush. I just remember all these small things to such a huge extent that I cannot stop seeing them as real people and something about reconciling that with the level of dehumanization that they are now executing makes me feel very, very sad and bereft almost I think for a lot of my friends because I realize that they must feel such a great emptiness, that they can also treat other people as if they are empty containers with no soul. I not only feel bereft and sad as an outsider, I think I also empathize because when I first started writing The Story Game, the person who I was at that time, I mean, I think I would still have been like, ”This is terrible,” but the feeling would not have been so rooted and so bone deep inside me. It would not have been a feeling that I feel every morning when I wake up and I look at the news, it would have just been like, “Yeah, this is the thing that I should say so I say it.” Like, “A progressive person should say this thing so I say this.” [laughs] But it would not have come from a real place of like my stomach hurts, my head hurts. I feel this churning feeling inside me and I feel like I must say something.

DN: I really loved some of your engagement with this and the questions that have come up for you on your blog around it. You talk about how you grew up in a Zionist Christian church and as a young adult left your faith. Nevertheless in your blog post in October of last year, you talk about, with your heartbreaking over Gaza, that you found yourself wanting to play old songs from your Christian past on the guitar, something that mystified you because you no longer held any of these beliefs and you even felt embarrassed showing this side of yourself to your husband who had never witnessed this part of you. You say, “I needed to sing the old songs to remember - in a time where my feelings are running particularly high - that the Other is not out there in the world, as a thing to reject and smear and direct immense amounts of hatred towards. It feels uncomfortable to admit this. But the Other is in me, actually. In some ways, it IS me - is a part of me that I can bring up every once in a while, and still have genuinely strong feelings of connection and gratitude towards, even though I no longer identify with it.” Then later you say, “We have to accept that the both these potentials - to dominate and be dominated - lie dormant in every single human heart, including our own. And when I look at the Zionist rhetoric that is currently flooding our news channels, what I see is a group of people who have been completely unable to accept the presence of this duality within themselves.” Even though this is all from outside the book, it does feel like this spirit animates The Story Game, a book that you and others have variably called a book of self-individuation or a book about loneliness, but it's also a book about control and power where in becoming a self, you also implicate the self at the same time. I wondered if you see that connection between the two, that in some ways, this book is also engaging with the other in the self.