Torrey Peters : Stag Dance

Four novellas, in four different genres—science fiction, horror, teen romance, and a western—Stag Dance not only interrogates genre, but gender through genre. Written over a ten year period, Torrey Peters’ new book spans a decade when her own views and insights about gender were themselves changing. Placing these four novellas in conversation with each other like this now, raises all sorts of questions about identity and the construction of a self, as Peters puzzles out, through genre, the inconvenient aspects of what she calls her “never-ending transition—otherwise known as ongoing trans life.” We look at questions of audience and risk, of writing into the taboos within one’s own community, and what it means that Torrey is less interested in exploring the binary between men and women, masculine and feminine, than the one between cis and trans, raising the question whether it is even a binary at all. We discuss the overdetermined transition narrative within trans literature and look at limit cases of cis gender performance from Kim Kardashian to Karl Ove Knausgaard to Ernest Hemingway’s late-in-life exploration of gender fluidity within his work. Whether talking about Shakespeare or Taylor Swift, this boundary-defying conversation explodes the distinctions between high and low culture, and like her work itself, it will make you laugh, make you think, and make you reconsider what is possible.

For the bonus audio archive Torrey contributes a reading of the first thing she wrote after she transitioned: “How To Become A Really Really Not Famous Trans Lady Writer,” This joins incredible readings from everyone from Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore to CAConrad and is only one thing to choose from when you join the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter. You can check it all out at the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is the BookShop for today’s conversation.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode is brought to you by Patrycja Humienik's poetry collection, We Contain Landscapes, a tantalizing debut by an author heralded by Aria Aber as a vibrant new voice in American poetry. Weaving in letters and innovative forms, and haunted by questions of desire, borders, and the illusion of national belonging, We Contain Landscapes is called "intensely beautiful" by Victoria Chang and "shot through with radiance and self-possession" by Joanna Klink. For every reader who harbors a voracious longing to encounter infinite landscapes and ways of being, this incisive collection dreams toward a more expansive idea of kinship, of how we become beloved to one another and to ourselves. We Contain Landscapes is available now from Tin House. I'm not only excited about today's conversation with Torrey Peters because of how much enthusiasm the airing of her craft talk last year on the show called "Strategic Opacity" was met with, and not only because her latest book is one of four novellas in four different genres that engage with gender across a ten-year period of Torrey's life when her own notions of gender and representation of gender were changing, but also simply because Torrey is a great guest and a great thinker, where the questions she poses in her work and in her conversation, whether they lead to an answer or provoke more questions, expand our sense of possibility both in art and in our own lives, I think. For the Bonus Audio, Torrey contributes something special: a reading of the first thing she wrote after transitioning back in 2013, a zine called "How to Be a Really, Really Not-Famous Trans-Lady Writer," which she reads for us in its entirety—all twenty steps. This joins many contributions, whether Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore reading from her forthcoming book, “Terryl Dactyl,” or CAConrad reading "Memories of Why I Stopped Being a Man," written in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of Le Guin's Left Hand of Darkness, a three-part essay where each part weaves in quotes from Le Guin, autobiography from CAConrad, and ending with CAConrad's poetry. Access to the Bonus Audio is only one of many things one can choose from when transforming yourself from a listener to a listener-supporter when you join the Between the Covers community. Past Between the Covers guest Anne de Marcken, who wrote one of the best books of the last year in my mind, is also the head of a press, The 3rd Thing, which makes these incredibly beautiful books, the quality of every choice in their design an act of love. Also, like Torrey's novellas, they often cross and blur the boundaries and borders of category and genre—books that trouble the relation between a performance space and the written page, for instance, or a lyric noir written by an evolutionary biologist. She put together bundles of these 3rd Thing books to offer supporters. There's also the Tin House Early Readers subscription, receiving twelve books over the course of a year, months before they're available to the general public. Those and a lot more. But regardless of what you choose, every supporter at every level of support is invited to join our collective brainstorm of how to shape the show and who to invite going forward, as well as, and perhaps most importantly, receiving a robust amount of supplementary resources associated with each and every conversation. You can find out more about it all at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now for today's episode with none other than Torrey Peters.

[Intro]

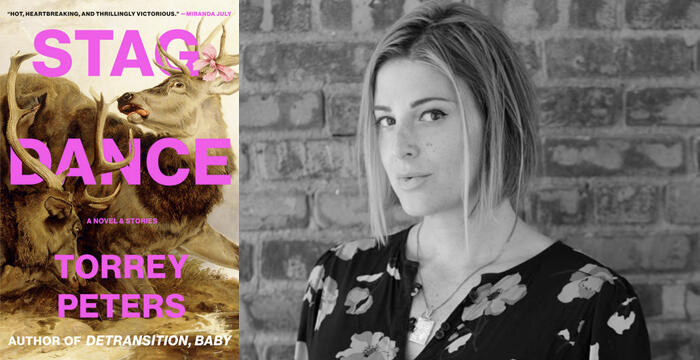

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest, the writer Torrey Peters, has an MFA from the University of Iowa and an MA in Comparative Literature from Dartmouth College. After moving to Brooklyn to join the Topside Press trans literary scene, Peters self-published two novellas as part of her project to promote a self-publishing culture among trans writers. One, called The Masker, was about online sissy culture, female masking, forced feminization fantasies, internalized misogyny, and cross-dressing, and was illustrated by the writer, artist, and portraitist of trans women, Sybil Lamb. The second was a biomedical sci-fi hormone revenge story called Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones. With the success of these books and with a shift in receptivity to trans narratives in mainstream publishing, Peters leapt from self-publishing to one of the big publishing houses with her best-selling and critically acclaimed debut novel, Detransition, Baby. Heralded by everyone from Roxane Gay to Garth Greenwell, Jia Tolentino to Carmen Maria Machado, Andrea Lawlor said of the book, "An unforgettable portrait of three women, trans and cis, who wrestle with questions of motherhood and family-making. Detransition, Baby will definitely keep you up late and might destroy your book club, but in a good way." Elif Batuman calls it "a noteworthy advance in the history of the novel." Vulture adds, "Reading this novel is like holding a live wire in your hand." And finally, Jordy Rosenberg exclaims, "Torrey Peters just took everything that couldn't be done and did it. Plenty of books are good; this book is alive." Detransition, Baby was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. It was longlisted for the Women’s Prize, named a best book of the year by everyone from Vogue to Esquire to NPR, and was named one of The New York Times’ 100 Best Books of the 21st Century. So it's with no small amount of anticipation that we welcome Torrey Peters to the show to discuss her latest book, Stag Dance, a collection of four novellas—or perhaps one short novel called Stag Dance surrounded by three novellas—four narratives in four genres that already have everybody talking. Imogen Binnie says, “This is what I want from fiction. It starts at a place of real vulnerability, goes all the way down its own rabbit hole, and ends up potent and strange.” Miranda July says, “Torrey Peters is often describing something that has never been described before and it’s never something minor, it’s something massive that has been missing from our understanding and enjoyment of the world. Stag Dance is hot, heartbreaking, and thrillingly victorious.” Finally, Julia Phillips says, "Her words divine and her characters brutally real, her talent awe-inspiring, her vision immense. Her writing tears your guts out. It leaves you gasping. This is fiction that makes you drop to your knees—fiction at its very best." Welcome to Between the Covers, Torrey Peters.

Torrey Peters: Thank you. I wish you were available for all my introductions. I mean, it feels really good. [laughter]

DN: It could be my new career.

TP: Yeah.

DN: I could tour around.

TP: I could tell [inaudible] give me my entourage. Not that you’re volunteering. You’re like, "No, I’m sorry." [inaudible] to podcast. [laughter] But I can dream. I can dream.

DN: Yes, you can dream. Well, even though Stag Dance is this incredibly entertaining read—sexy, provocative, often laugh-out-loud funny, heartbreaking and heartwarming in equal terms, I think—moving, edgy, and more, I feel like before we talk about it, I have to at least acknowledge the moment in which we're talking and how Trump's barrage of executive orders from day one have had at the forefront a focus on a massive cultural re-entrenchment to a binary notion of gender, with a direct attack and rollback of transgender rights. A banning of trans women and girls from sports and schools under the threat of having federal funding pulled. Banning from serving in the military. A prevention of trans athletes from obtaining visas to participate in the Los Angeles Olympic Games. Passports and visas being issued to trans Americans in contradiction to their declared gender. Websites providing transgender health information going dark. Direct threats and attacks on hospitals and clinics offering gender-affirming care. The removal of federal funding from any medical school or hospital that researches gender-affirming care. We don't have to talk about this at all. This isn’t the focus or even the tenor of your book. But I wanted to at least create the opportunity for you to speak into the moment if you want to, as you now enter this public-facing period of introducing Stag Dance to the world and accompanying it out into this world. If not, to have at least spoken myself about the climate within which we're having the conversation.

TP: Well, first off, I want to thank you, especially for listing all of the things. You know, I think a lot of people hear one or they hear another, and when you start hearing all of them and even also the things that the people he's appointed are doing outside of even the executive orders, relevant to this podcast, for instance, the fact that anyone who they said "promotes gender ideology"—which basically just means trans people or writing about trans stuff—is no longer eligible for NEA grants. So there's a real chilling effect in arts institutions, and that wasn't even in an executive order. That was just people being like, "Let's freestyle on this and see what other kind of bigotry we can come up with." So I appreciate that, everything you said. I do actually want to speak to it. I mean, I think it's been a real change for me. When I published Detransition, Baby, I never would have guessed that I would say, "Well, this is the high-water mark of trans freedom." But weirdly, I seem to have hit it in that moment—at least the high-water mark for now. At the time, there weren't that many books by trans writers out. I felt sort of thrust into this position of representation where I was representing all trans people. I wouldn't say I resented it, but I was uncomfortable with it. I didn't want to speak to trans politics. I didn't want to do this sort of stuff. I wanted to say, "I wrote one book. A lot of what's in that book is pretty weird and idiosyncratic. I would certainly say that not all trans people—and in fact, maybe even a majority of them—would endorse my positions, so I can't speak for trans people." I made that point over and over. I almost feel the entire opposite as I did then. I'm publishing this spring even as there's this barrage of, as you say, executive orders and bigotry that's specifically targeted at trans people. But I also happen to be speaking at a time where there's an unprecedented number of trans books being published. I mean, I can't even list them all right now because it would take too long, but just thinking briefly—Jamie Hood, Trauma Plot, Harron Walker, Aggregated Discontent, Jeanne Thornton, A/S/L, Aurora Mattia, Unsex Me Here—I mean, I could just go on and on and on. Hot Girls with Balls, which is a great title. I haven't read the book, but I'm just waiting for it. It's about like a tennis romance, maybe a volleyball romance. And you know, all these different genres as people [inaudible]. As a result, I really don't feel that I'm sort of a de facto representative of trans stuff. And as a result, I also feel that the act of solidarity is to, if I'm given a platform now, really speak to it. To speak to "This is going on," to not say, "I'm an artist, I want to talk only about my book." It has become so oppressive and so present that it actually is in all the art. I wrote a piece for New York Magazine at the end of January, right after the passport thing happened, where Trump said that if you renew your passport, your gender marker is going to be changed involuntarily to whatever your sex at birth was. I've had my passport for 10 years, and I have to renew it next year. On top of that, I live part-time in Colombia, and you get stopped by the police a lot in Colombia, which means that in the future, every time I get stopped by the police in the middle of nowhere, I'm going to be outing myself as transgender to just literally two guys with guns on the side of the road. So it's like a real safety thing. I've thought a lot about it, and I figured I'll have to navigate it. But this seemed like a big thing, and I wrote an essay about it. I gave it to New York Magazine. I said, "This is timely. I would like to see it published as fast as they can." To their credit, they moved super, super fast on it. I think I got edits two days after I emailed them out of the blue. Yet in two days, in the two days that it took it, there were like five other extremely cruel executive orders. So the pace of it was so breathtaking that what seemed like my worst problem—I don't remember the exact day, but let's say January 27th or something—what seemed like the worst problem by January 30th, it was like, "Well, the passports are the least of the worries." And that speed of just losing what little kind of rights you have is—it's this political problem, but it's also an artistic problem. Because I'm trying to write another novel, and I'm trying to gauge, this book is a lot of genre at work, but I want to write a realist novel. And when you write a realist novel, you're kind of writing about a little bit like the near future. You're trying to write about now, but now when you write it is actually the near past when you're writing. So you're kind of guessing a little bit at the near future. The kind of paradigm—I guess you'd say—of trans rights in which I was writing suddenly went away. I'm sitting here writing, trying to be like, "How bad do I have to imagine the future in order to correctly calibrate what my characters in the near future will be experiencing? Is it the type of thing where they are sort of de facto banned from public because they can't use public spaces? Or is that even going to seem naive? Is it going to be worse than that?" And meanwhile, if I picture some sort of dystopia, I seem hysterical. But if I don't picture something that's really bad, I can seem like a naive propagandist. I've been thinking a lot about books. I've been thinking about The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, and starting in 1912, and just the Germany he lived in and what he believed. I mean, I think he was a supporter of the German Empire when he started writing that book. By the time he finished it, I think he made that famous speech, like, "Long live the Republic," or something in Germany. The huge transformation that he had to go through, and also then the techniques that he had to develop to sort of write a book that couldn't possibly keep pace with the change. I've been thinking about somehow he made The Magic Mountain, where it's like, it's seven years that take place on the mountain. It's about 1912 for seven years. Then time catches up, and Hans Castorp just immediately is machine-gunned to death, as time snaps back into the time of the war. These kinds of questions, I think about a lot as an artist. And then there's the question about simply, "How do I actually do the daily work of being an artist in this climate?" I'll say one more thing on it, which is that for any trans people that are listening, I even mentioned the passport thing, when I transitioned, I never thought I was going to get an "F" in my passport. That was something that Hillary Clinton did, where you didn’t even need to change your birth certificate or anything, because some states you can't change it. But that was new in the last 10 years. So there's a kind of world of trans people who actually do know how to live in this kind of environment and have made networks. The idea that you could just walk into a—I think you should be entitled to, I think everybody should be entitled to walk into a doctor's office and request what they need for bodily autonomy. But there's an entire way of thinking, an entire history of trans thought that basically is like, "Authority is only legitimate if they're doing ethical things." That if people like Trump or whatever authority figures are going to stop you from doing what you need, then it's entirely legitimate to do what you need. Whether that means getting the medicines that you need, whether it means figuring out whatever mishmash of documents you need, doing whatever you can to sort of make a good life for yourself without needing to be legitimized by authority figures or validated, there's a whole history of that, which is ironic, because I think people think that the emphasis on trans language is that we're constantly running around looking for validity, like, "Please use the right pronouns so I can feel valid." It's like, actually, "I don't care at all what pronouns you use." I think most trans people on a matter of just being polite, it might matter, but it's not going to distort my sense of self if someone gets that wrong. It's not going to distort my sense of self if the letter and the gender marker in my passport is wrong. And what really matters in the end, rather than seeking any kind of legitimacy from—I would say—illegitimate authority, is just making a life that works. I'm heartened to see in my circles and the worlds I run in a resurgence of belief in that. Not only a resurgence in belief, but a logistical resurgence of, "We're going to live, we're going to do our thing, and you're not going to stop us." As much as I've been—I wouldn't say crushed because I'm not—but as I've been disillusioned, to put it mildly, with this country in the last few weeks, I've also been inspired by the way people react. I believe in us.

DN: Let me ask you a further question about authority and realism. Because Stag Dance by no means takes place in a safe space. It pushes boundaries, provokes, and engages deeply with taboos, which I want to discuss later. But thinking about the executive orders in the real world, I realize one way all these novellas are in a sort of protected space is that the elements at play are not coming from a superstructure coming down upon the characters. There is shame, joy, tenderness, fear, and anger as people work out—or don’t work out—who they are. But it seems to me that it’s happening on a horizontal plane, where that can happen person to person. The structural violence, to me, feels like a subtext that perhaps we as readers bring to the text. But I wondered if that felt right to you.

TP: No, I think that's right. I think it's absolutely very, very perceptive. I've always been much more interested in what trans people are doing with each other than what cis authorities are doing. So the context of my stories are often other trans people. How are we working with each other? The big obstacles in understanding myself have often been through negotiating, "What does it mean to be trans? What ideas do just some other trans person have that I can borrow? What ideas do they have that I can reject?" That's always interested me much more than a kind of seeking legitimacy from authority, where if I sort of make cis people the enemy or something like that, and I'm just hoping one day that they won't be mean to me, that also invests them with authority. I think the basis of a lot of my writing is basically, "I love a lot of cis people. I wouldn't even say that I believe that there's a strong binary between cis and trans people." I think that one of the things I'm trying to do in my book is break down the idea that we're other to each other, that actually we all kind of have these feelings. But I definitely would not say that if one day the authority accepted me, all my problems would go away. I don't believe in a world that way. I think most of the problems actually come from negotiating, as you say, horizontally with other people. How do I actually make a life with the people I love, even though we're all incredibly frustrating to each other all the time? [laughter]

DN: Yeah. Well, before we talk about each of the stories on their own terms, I want to spend some time with the book as a whole, because it's four novellas written at different points in your life, and to explore what that says about everything from identity to audience and from craft to genre. You make a nod to this macro element in your acknowledgments, where you say you wrote these four novellas over a ten-year period to "puzzle out through genre the inconvenient aspects of my never-ending transition otherwise known as ongoing trans life." So thinking about how presenting these four novellas together shows a person in flux, in the process of thinking through, and that these novellas are in conversation with each other, I think, because of this, let's start with the circumstance of the first two you wrote, Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones and The Masker, because how you published them, and also that you published them as novellas, arose out of your own assessment of trans representation in literature at the time ten years ago. So talk to us a little about the project you started that was the vehicle for these two books and why and how it started, what need you saw it fulfilling, and what hopes you had for it then when you put them out.

TP: Yeah, I moved from Seattle to Brooklyn to be part of a writing scene that was mostly trans women but some trans men around Topside Press. Topside Press was actually started by a few trans men. One of them I was dating, actually. The press had this idea that trans writing in the past had mostly been trying to speak to cis audiences and had been trying to convince cis audiences, "Hey, we're normal. Hey, you should accept us." The primary and most popular trans genre was memoir—just a transition memoir where you say, "I used to be X, a boy, a girl, and then I transitioned." It was a little bit displaying yourself for the, not always current, but often current sort of readership. So these people were thinking, "What if we did fiction? And what if the fiction was mostly by and for other trans women?" In the same way that you could think of Toni Morrison writing for other Black women, sort of similar on a trans level. What if trans culture, or the production of culture, was actually between trans people? If you just have one trans person alone among a bunch of cis people, that's not really trans culture. That’s one trans person. But culture is the communication that arises between trans people, both in terms of the circulation of literature but also within literature, trans people talking to each other about ideas. A lot of the books had a sort of, we called it the Topside Test, some of the Bechdel Test. The Bechdel Test asks whether there are two women in a movie talking to each other about something other than men. The Topside Test was, "Are there two trans people in a story talking to each other about something other than medical transition?" And there wasn’t much that passed that Topside Test. The scene was kind of around that. But the problem is that when you have one press, you can’t really publish everybody. It produces a real scarcity mindset. So the thing that was supposed to be anti-gatekeeping, which was publishing trans books when they were not anything other than memoir was not getting published by the big presses itself became a kind of gatekeeper. It’s a tremendous amount of work to publish a book, to edit it. They were doing three or four a year. Who got chosen was highly contested, and all of the normal things that get in the way of publishing got in the way. They mostly published white women. It was people they knew. You had a hard time getting in off the slush pile. I never published on Topside, but I had this idea, I mentioned Tom, who was one of the owners, editors, and publishers of the press, I lived in his living room, I lived with him but I was always in the living room and I would see essentially, “This is how you publish a book.” You get Adobe InDesign, you find some sort of platform, and you have to learn things like kerning, but you can do it. It’s not that hard. I had this idea that basically, what if instead of needing a press, a bunch of trans women started publishing our own novellas? Novellas at the time seemed like the perfect length. You could read one on this era. You could read it on the train in an hour. You could write one in a couple of months rather than needing three years, which meant if your employment was a little all over the place, you could just pull it together for a little bit and do it. You could self-publish. A novella cost me at the time about $2.15 to publish each novella so I could do a print run of a couple hundred for $500 or $600 if I could pull that together. Then I could make a couple of bucks on each one, but it wasn’t this huge financial outlay. The idea was to publish these novellas, get other trans people to publish novellas, and create a scene of trading this stuff back and forth. I gave them away for free on the internet or as pay-what-you-want. They were about eight bucks each. I would stuff envelopes and send them in the mail. I thought maybe people didn’t have money to pay for Adobe Suite, so I tweeted out my Adobe Suite passwords. Same with Lynda, which had classes on how to use productivity software, I tweeted out my passwords for that, so anybody can learn, anybody can do it. I was kind of like, "This is going to be a great movement. It’s going to be wonderful." Basically, zero people took me up on it because it's actually really hard to publish a book. A lot of people, even if you're a weird punk trans woman, want to publish under the auspices of somebody who will help get your book into the world. So I was kind of disappointed. I thought of the project as a failure for the first two years, or maybe the first year, because other people weren’t doing it the way I thought they would. Meanwhile, these two novellas started to circulate. They were passed hand-to-hand around Brooklyn, and then digital copies started getting passed on the internet. They became little cult objects. Within a couple of years, people did start doing it. They didn’t do it with my password or my ways of doing it and the way that I envisioned, but it happened organically. People were doing it how they envisioned it instead of taking my vision. I actually do think it worked, just not the way I thought it would. I had thought of them as a cycle of five, where I was going to do five novellas, each in a different genre. I did two—the two you mentioned—then I started one that I thought was going to be a melodrama soap opera, which was a terrible idea because a melodrama soap opera is not novella-length. It goes on forever. That’s the whole point of it. That one became Detransition, Baby. After that came out and my life changed, I was doing screenwriting, and I was like, "I think I just want to go back to this project." Even though I thought of it as a failure, it was the happiest I’ve ever been as a writer.

DN: Well, you’ve talked elsewhere about finding your readers first rather than the publishers first, and also a shift within the mainstream culture with trans writers suddenly becoming editors at major magazines, and with shows like Pose and Transparent as part of a new interest and receptivity to trans narratives. You were approached by an editor from one of the Big Five publishers for Detransition, Baby. It couldn’t have been a bigger leap from giving away books for free to this. When you delivered your craft lecture last summer at Tin House Writers Workshop called Strategic Opacity—which has since become a Tin House Live episode on the show and is destined to be an all-time favorite—with many people already exclaiming not only how helpful it has been to their writing but also that they've listened to it multiple times already. In that conversation, you talk about editorial suggestions that you took for your novel, which you now, in retrospect, wish you hadn’t. This craft lecture is partially your thinking through why you would respond differently now to those editorial suggestions. I wondered if you could speak for a moment about that revelation and regret, and also, given that some of the novellas fall before this feedback and some after, if you see any way in which that revelation has played out when you look across the four novellas from that moment of recognition.

TP: Yeah, absolutely. The idea of that craft lecture was about Hamlet and Shakespeare, which I realized was embarrassing—to go to Tin House, which is doing all this progressive stuff, and be like, "Hi, I’m here to talk about Shakespeare," the most canon thing possible. But the idea is basically that Hamlet makes no sense. What Hamlet does makes no sense. His stated motivation is that he wants to kill his uncle. Instead of killing his uncle when he could have, he pretends to be crazy. Why it’s a great play is that this actually reveals his humanity rather than sort of “I have a goal” and the story is about achieving it. In the first two novellas, I was very interested in motivation, desire, and especially choice—the way that motivation and desire led to choices. That’s relevant because I was much closer to transition. That’s a really relevant question when you’re facing transition. You have this feeling, but you can’t quite put your finger on it. I mean, the idea that, "Oh, I always knew I was a girl," I think this is a little bit of an invention of transition narratives rather than a reality of how it feels. So I basically just felt weird. Then it was like, "I think I'm going to try to transition. This choice is going to change everything and in fact may ruin my life," and it did in a lot of ways, kind of ruin my life for a while. So choices were just incredibly present for me, and most of the stories I was writing were about what it means to take agency in your life and make a choice. In Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, I think the main choice in that story is, "Should I spread a contagion that makes everybody else have to make the same choice I did, which is what gender will you be?" Or The Masker, where it's, "Do I choose the Sally figure, who's a transsexual representing a respectable state, or do I choose a masker, who's a fetishist but pretty fun?" These kinds of choices interested me because I had lived most of my life in a very stuck way, where I was like, "If I can figure this out, I can make a choice." Even Detransition, Baby is, in some ways, a biblical choice story. There's one baby, two women who want to be a mother. Like the King Solomon, like, "Can you divide the baby in half? Can we revise the Bible and divide the baby in half between these two women?" which was a bit of a choice as well. So I wrote really thinking about how not to be stuck, how to make choices. I still care about that. But so much of making a choice is actually about having a character who knows their motivation in some way. The more I write, the more I'm sort of like, "Actually, people make choices and they have no idea what they want." Even when I transitioned, and I thought I sort of re-narrativized it as, "Oh, I want to be a woman, so I'll transition," but actually, it was way more murky. I was stuck because I didn't know. That many people actually don't know and are doing things that don't really make sense. That’s actually the grand narrative. Otherwise, what you have is a sort of detective story, where it's like something happened and somebody's making a series of choices to elucidate it. It turns the reader into a sort of detective, where you're like, "This character wants this thing. What may go through a bunch of hurdles to see if the character can achieve their want?" Which is a very screenplay, movie way of thinking. What I began to think about is, "What if a character doesn't really know what they want? And not only that, they're sort of opaque to themselves, not in a boring way but in a strategic way, where you can sort of know everything about a character but make one part of them opaque to themselves and then see how they do things?" Which is what I think Shakespeare did with Hamlet. So only the last story, or only the last story that I wrote in the collection, which is Stag Dance, about a lumberjack who, in a way that I think is sort of opaque to himself, decides to go to a dance, I found this out—this is from real history, men would do, the logging camps would be in the middle of the woods, and they'd be there all winter long because winter is when you can drag the logs. They'd get so lonely, and they'd throw these dances and dance with each other. If you wanted to go dance as a woman, you'd cut out a little triangle of fabric. The symbolism is way too on the nose. It would be like a little brown burlap triangle, like a bush. You'd hang it over your crotch, and that meant you're a woman. And you'd go to the dance. Of course, they would hook up with each other, in the same way that a lot of—you know, they weren't like, "Oh, I'm queer or anything," they were lonely, the way that happens in a lot of same-sex spaces. So the lumberjack, the Babe, who's the main character in the story, who's this giant, ugly, sort of Paul Bunyan-esque lumberjack, kind of makes a decision to wear the triangle to the dance as a woman. The story kind of follows from there. But I don't explain that desire too much. He describes a little bit how it feels to decide to want that. But it's not like I have stories of him as a child being like, "I always wanted to wear a dress," or we don't even really know where he comes from. We don't know what his background is too much. That was a real change because when I first started writing that story, I had a whole thing where he was a Silesian from parts of the Prussian Empire who was persecuted and had always been really big, but was jealous of his sister's dresses and got sent to the United States, or they fled to the United States. It was a whole backstory. It actually became much bigger and much more interesting when it wasn't specific, when it was like, these desires are unruly, uncontrollable, and actually can't be contained in backstories or simple narratives. I discovered it halfway through writing that, and like I said, I cut that whole backstory based on it. But I'm hoping in the future to have stories where it's integral from the start that these characters may not totally know themselves, and that you can write with characters who are opaque. It's your job as a writer to strategically build everything around to hold their opacity. Otherwise, a character who doesn't know anything about themselves and just wanders around with no point—that can be quite boring. I spend a lot of time thinking about Haruki Murakami and how he makes these characters so compelling. Can I borrow from that? How do you construct around it? But yeah, so Stag Dance is the one that does it.

DN: Just for people who haven't listened to the Strategic Opacity episode yet, just to name what the revelation was with Detransition, Baby—you were asked by editors, "Why does this trans woman want to be a mother?" and you wrote parts of the book that you now regret, explaining it when you've realized ultimately, well, why does any woman want to be a mother? Can you really come up with some sort of cause and effect of why? Some rational explanation of why someone wants to become a mother when it's often mysterious even to anyone, cis or trans, who wants to be a mother.

TP: Sure. It's like anytime you ask anybody, "Why do you want to be a mom?" the answer is always paltry, less than the act, which is kind of holy or sacred. Whatever reason sounds small.

DN: Well, part of my interest in you including your work over time together, given how you've changed over time, is a selfish interest. But I think my selfish reason might provoke some interesting thoughts on your end. My agent is out on submission with a manuscript of mine that spans 17 years of my writing. Not all of my writing—it's connected, though, the writing that’s in this. But it's a book that thematically is troubling category and also the impulse to differentiate, mainly across species, by disrupting hierarchy. It isn't doing this with gender per se, but I think of Cal Angus' book, A Natural History of Transition, which also looks at transness in this broader sense of moving across within the natural world. My book is also doing this with genre. The reason I bring this up is, in doing deep edits with my agent, I found myself most resistant around accepting edits on my earliest pieces—the most formally normative pieces. Not because I feel most attached to them; it's actually the opposite. I feel most distant from them and maybe the most insecure about them. I feel they're the farthest from how I write now. But I think I found myself resistant because I wanted these stories to be there on their own terms, representing me at a different time as another way of troubling category, of showing a self that contradicts itself perhaps or has a different aesthetic—showing the same person but differently, rather than going in and rewriting things how I would write them now. I bring this up as a preface to asking you about returning to pieces from a decade ago. It isn't as if you haven't ever distanced yourself from past writing before. You've disavowed your 2012 essay The Cross-Dressing Room, written before you were out, both because, in your words, "It was desperately trying to be like, 'This is normal. You can still love me, everybody.' I didn't know why I was writing at the time. I didn't know what writing is for. I didn't know how to be honest." So, you still obviously like these two earlier novellas, much as I like my earlier writing. But I wondered if, as you return to them now, how that was, what you noticed in the revisitation, and also if you did edit them, how you edited them, and if that was strange or simple to go into the language or into the narrative with a different sense, I mean, you’ve already articulated your different sensibility now.

TP: I guess I think of them a little bit like tattoos. If you get a tattoo, you're marking your body at a particular time in your life. It's just a memory, reminding yourself who you were when you got that tattoo. You have to accept that probably you're going to think that tattoo is stupid, or maybe it's great and reminds you of something. But my tattoos mostly remind me of who I was when I got them, rather than, "Check out my cool tattoo now." [laughter] The tattoos just become a part of you. By analogy, that's how I feel about these pieces. They're not the tattoo that I lasered off. That Gawker essay you're talking about, I would go to a tattoo removal person and be like, "This is not what I want to identify with or mark myself with." [laughter] But I look at them, and I actually think they speak to a kind of angst—a younger angst and a younger kind of fury that I can't capture right now. It's not that I'm not mad sometimes, but I think there's a ferocity of youth and frustration. Sometimes it can come across as naive or even sloganistic or something, but I couldn't do it now. Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones is just a capsule for that. The point of it, there's a little bit of story, but it's mostly to hold the emotion. When I ask, "What is writing for?"—that's sort of this is how it feels like, "I want to destroy the world. I want everybody to face their gender the way I've faced it." If you ask me to vehemently feel that now, I'm kind of like, "Well, people are going to do what they're going to do." [laughter] It's not like I have no fury. I couldn't go back and change it. I would be wrangling something fundamentally different. The kind of person that story spoke to, who I talked to in 2015 who wanted to give it to their friends—I can't write for that person anymore, but I still want them to have it. I want them to be able to get it. In fact, the only editing when I published those novellas, they were riddled with typos because I'm not very good at seeing my own work. In fact, some people would complain, but I came to really love the typos and some of the sentences that are clunky because I think that at the time, I was trying to make a point that I wanted everybody to write their own novellas, to share their stories. Having come from Iowa, where people wrote very well in grad school, I was in a mode of rejecting that. I was like, "You don’t actually need an immaculate page to move people. You need the emotions, the fury, the ferocity. That’s what moves people." Whether you spell a word wrong, or if you have a sentence that isn't as elegant as you would have liked, that's fine because it can be washed over in the honesty of moving other people—which is what I think writing is actually for, or at least the kind of writing I do. So I had to get rid of all the typos. I made a brief pitch to my editor, "Let's have it be full of typos." [laughter] But right now, I was like, "We have a house style that is not completely messy and you have to get rid of the typos." So I did. I corrected all the typos in the first two stories. Then The Masker, too, I don’t feel the same kind of shame. I'm not working through shame now in the way that I was when I was writing The Masker. I don't feel the sort of, when you bring shame into the light and see that it's actually not that big a deal, shame is only powerful when you're hiding from it. There's this moment when you bring it up into the light, and you think, "It's just not that big a deal, what I was so ashamed of" once you speak it. That feeling of, "Oh my god, it's not a big deal, and I'm so relieved," that's ten years in the past for me. I just don't think I could do it the way that story needed anymore. The Chaser I wrote in 2020, and I seriously revised that one. That one has a totally different ending than I originally wrote, which is not that far away from me—2020—but it was a very, very bleak ending. I guess I should have said that based on the Goodreads of users. There's a scene of animal cruelty, and I should have done a trigger warning or something like that. Trigger warning—scene of animal cruelty. These boys sort of act out their own toxic relationship on a farm with a pig, and they kill the pig, and it ended there in the original story. I went back and was like, "This isn't actually what I feel. I don’t believe that when two people are cruel to each other, the story just ends, and you just sort of gut punch the audience and walk away and deal with it. How do you feel now?" [laughter] That’s not the world I believe in. So I wrote a whole different ending to reflect what I was really trying to say, which is that the story is from the point of view of a kind of bro. He was in love, but he couldn't say it and actually, by not being brave enough to say, "I'm in love with this other boy who may actually be a pre-transition trans girl, and I can't tell if my love is heterosexual or homosexual, this fear around labels is preventing me from accessing my love," that everything in his life falls, it's not the scene of cruelty that matters, it's how much you actually lose to hold on to your sense of wanting a future in which you can just be the thing you're supposed to be. The story ends with him leaning up against his dad's car, losing love, losing his father's respect, losing everything because he can't admit the love that he feels. That, to me, felt much truer than simply, "People are going to be toxic and mean to each other when they do this." It’s something softer, but it wasn’t worse.

DN: One thing that piqued my curiosity in your afterword was referring to your "never-ending transition, otherwise known as ongoing trans life." I wanted to know more about what the never-endingness means, and we have a question for you from another writer that feels compatible or kindred to my curiosity. Jamie Hood is a poet, memoirist, and critic. Their debut, How to Be a Good Girl, was a hybrid work of self-making, mingling diary entries, poetry, literary criticism, and love letters to interrogate the archetype of the "good girl." Their next book, out March 25th, is Trauma Plot. Because I book the show super far in advance, sometimes years in advance, every year, there are three or four instances where I feel a pang, an actual bodily ache, about a book I discover where I wish I could interview them about it. Learning about Trauma Plot is my 2025 anguish so far. Here’s past Between the Covers guest Kate Zambreno about it: "This book devastated me. I found my whole being thrumming with the energy of Hood's refusals, her intense thinking and feeling, the formal play with the modernist novel, and her clear-eyed reporting in the wake of trauma. An American Annie Ernaux, Hood writes to avenge her people—with incendiary brilliance, wit, pain, and devotion to the search for something like truth." Here’s a question for you from Jamie:

Jamie Hood: Hi, David. Hi, Torrey. Congratulations on Stag Dance. I love this book. I'm so excited for it to be in the world, and I feel really, really honored to be able to engage with your work as both a writer and a friend. I've read The Masker, The Chaser, and Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones before when you first published them. But I have to say, it was a really different experience to read them all at the same time, all in a row, and also alongside the titular novel in the collection. Something that occurred to me was your sense of gender as a spatial or directional formulation. In the author note, you write about transness as movement. You go on to point out that these pieces travel "across genres, across time periods, and yes, across and within genders." I guess I'm just curious if you might talk a bit more about gender and motion, its non-stasis. If there's time, I'm also really animated by the way Stag Dance foregrounds the erotic in the production or reproduction of gender. Yeah, thank you so much. I hope to see you soon. Love you.

TP: Well, thank you, Jamie. I was surprised to actually hear your voice right now. Jamie and I have known each other for years. I agree with you about her book. I think it's going to be really exciting, a lot of really exciting and hard, but cool conversations when it comes out. To answer the question, I guess I do think of it as movement, but I think of it more as desires and the way that desire causes movement, which is, I think, an Andrea Long Chu formulation that you want something, and you're not sure what it is that you want, and then you go searching for it. You search for the things that are available in the world to have it. I don't just mean that for trans people. I think everybody's doing it. You decide you want to be seen a certain way, or you want to enact yourself in a certain way, and then you go looking. In the case of a logger, for instance, you go looking for a flannel shirt and other men to chop down trees with, to see your effect in the world in the clearing of the forest. There’s a kind of satisfaction, a fulfilling of desires as you look upon the work you’ve done. That actually then gets called gender. Like, "Me and my other men went and cleared the forest," and that's gender. That’s a desire that's fulfilled. These desires can change your body. "I want to be prettier, so I got a nose job." It’s a very material kind of thing. It could be about who you want to surround yourself with, "I wanted to feel this way, so I got a husband who had a homestead," whatever it is in whatever era. Oftentimes, it doesn't meet your desire perfectly. It’s like, "I wanted to feel this way, and I ended up milking cows in Kansas. How did that happen? It didn’t quite line up, or only partially did it line up correctly." But I think the thing about desire is that if you accept it, you can repress it, which I think is what I did for a long time before I transitioned. I felt a kind of stuckness or stasis in my gender because I was largely denying the desires that I had. They weren’t just about growing my hair long or wearing a dress. It was more about feeling parts of me being fulfilled. I didn’t know exactly what they were, but I had to make a series of choices and seek things out in the world, which is the choice thing that I was talking about earlier. But in the book specifically, I think that’s what animates most of the motion is that people have these desires. It’s very little about identity or gender as a kind of identity marker, like "I'm a man" or "I'm trans," "I’m this or that." There are maybe four characters in the book who identify as “trans.” If anything, the binary that the book is breaking down is not the typical male-female gender binary, but a breaking down of cis-trans binary where it’s like we all have a lot of feelings around who we want to be, and we go out seeking them. We repress them, we thwart them, we twist them in all sorts of different ways as we try to enact them with other people because I think gender is also a negotiation with other people, and that that is gender, and that movement of seeking is, I think, the movement Jamie is talking about. That is not unique to transness in any way, other than that transness has provided us trans people with a series of experiences that gives us a lens on how to describe it.

DN: You've perhaps started to answer the next question but on a conceptual level, and the next person who's going to ask you a question might be leaning more toward the writing level. But as a preface, I wanted to, in more detail, bring up the setting or scenario of Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, which is the most nonlinear, timeline-leaping into the future and the past on either side of what's called Contagion Day when a patient zero is created. It involves a character, Lexi, in a T-for-T community, a trans-for-trans community, where love of trans girls is first and foremost, a transwoman who wants to turn a vaccine for pigs into a bioweapon to use on humans, both as an active revenge but also to enact her vision of the future which has utopic elements to it. This pig vaccine which causes pigs to develop antibodies to their own gonadotropin-releasing hormone, the hormone that prompts us to produce our sex hormones, I looked it up, and this is actually a real thing. There's a drug called Improvac that is primarily used to chemically castrate male pigs to avoid what is called "boar taint" of the meat, which is an unpleasant smell or taste in the meat from male pigs when they've reached puberty. But presumably, because it's acting on a precursor hormone, it would have a similar effect on female pigs with regards to sex hormone production and presentation, putting them in a pre-gendered state of sorts. So this utopic vision of the future—being trans, defaulting everybody to a place where they're having to make decisions that they normally don't think of as choices—this is the most extreme or overt version of something I think you do a lot in Stag Dance, which is explore the difference between one's beliefs and one's impulses and desires, and sort of the battle between the two. This even happens with Lexi's vision, where originally she wants to use this vaccine on the transphobic frat boys who have been terrorizing them, but instead, the needle ends up jammed into the arm of an ex-girlfriend she's had a rough falling out with. As a first step toward discussing this, we have another question for you from novelist Julia Phillips, whose debut, Disappearing Earth, was a National Book Award finalist and was declared a genuine masterpiece by Gary Shteyngart. Like Disappearing Earth, her second novel, Bear, which came out last year, was both a bestseller and critically acclaimed, with starred reviews left and right and appearing on a lot of best books of the year lists. Megha Majumdar says of the book, “Bear is the brutal cage of the real world and the magical animal within—a book of untamed, glorious, abundant interpretations.” So here's a question from Julia.

Julia Phillips: Hi, Torrey, this is Julia Phillips. I am a huge fan of yours, and my question for you is, could you talk about how to write ambivalence? Your characters are so often pulled in multiple directions. They hate what they love. They dread what they most desire. I think in the hands of a less skilled writer, this might look like inconsistency, but your characters feel so consistent—perfectly complicated, rich, and real. How do you do that? How do you build out and balance their opposing impulses on the page in order to make them more rounded, more real, more compelling people?

TP: Wow, that's really nice. I've never called it ambivalence to myself. I think that, going back to your example of Lexi, where she has this sort of grand plan to make everybody have to choose their own hormones the same way trans people do, then there's actual life that intervenes and basically your ex-girlfriend's just a bitch, and you just can't stand it, and you can't control yourself, [laughter] the ambivalence, to me, feels like it's on different levels. I have grand ambitions to do this or that, and then I have my actual petty self, which is filled with jealousy and competition and all these small things. The reason I feel like it's consistent for the characters is that's just how I feel about myself. I have these consistent, at least for a period of time—I'm always changing what my vision of myself is—but how it feels to be inside myself is I have a vision of who I want to be, and then I have the daily ways that I betray myself in all these small ways. That's the scheme of many of my characters. They have these lofty goals of who they want to be and what they want. Then there are all the small failings that actually make up who they are. They're short-tempered, they're impatient, they're lazy. I make them sound so charming, my characters. [laughter] Yeah, but I think we all are. We lie to ourselves because actually admitting who we are is often very painful. So you then make an action that's based on a lie to yourself. That lie then looks inconsistent with your larger goals. But it's actually that you've told yourself a story that it's going to help you reach your larger goals. The last character in The Masker, for instance—the sissy main character—she betrays herself. I think hers is the worst betrayal in the story, where she has a possibility to make a big change in her life, potentially transition. She doesn't do it, ultimately, because she's afraid. That's the biggest thing, but she doesn't want to see herself as somebody who's afraid. So she makes a horrible decision by convincing herself that it's the appealing decision, not the less frightening decision. That, to me, feels totally consistent—that somebody who's lived a life of fear will, even as they want something great, have fear trip them up. I think the whole idea of tragic flaws is that the tragic flaws are inherent to a character. That character could only be consistent with those very flaws. I'm often looking for the flaws that are of a piece with everything that's noble and great in a character.

DN: Well, you've talked here and elsewhere just now about how contradictions are what make characters feel human. But you've also talked about your desire to question narratives that over-determine trans culture. Of course, just like contradiction makes both cis and trans characters more interesting, narratives that aren't over-determined make for better art, whether the characters are cis or trans. Before we take this out to the general case, let's talk specifically about trans representation and overdetermination. Because I think, like with any group that is marginalized, threatened, and incredibly underrepresented, where there's a climate of both risk and scarcity, the impulse of the community in its broadest strokes is often to want to put forth a good public-facing face, to show one's people in the best light. To me, in these scenarios, it often feels like the pathway away from the overdetermined narrative is also one of breaking taboos within one's own community, then, sometimes suffering blowback for portraying characters in ways that can give ammunition to the enemy. Philip Roth is one example—he faced this early in his career from the Jewish community, which is hard to imagine decades later now, given how embraced he is both by the Jewish community and at large. You writing a book with a detransitioned character and with detransition in the title is probably the most prominent example of this in your work. The phenomenon of detransition being used as ammunition against trans people and trans rights, which you wanted to reclaim as something the trans community in particular should be writing about, not having it written about primarily in a weaponized way by others. But you also wanted a detransition narrative because it was not familiar to people. It wasn't over-determined, unlike transition narratives, which had a certain repeated and well-known set of tropes. You also more generally often have your trans characters acting badly, as you've just mentioned. You seem averse to narratives of resilience or of overcoming, and I wonder if that's partly why the book itself isn't presented with the novellas in chronological order, that you're not trying to present, "Well, this is how I've grown," or "This is how things have progressed." Not just Lexi vindictively infecting her ex, but as you mentioned the novella The Masker, the main character choosing "wrong," which perhaps harkens back to The Cross-Dressing Room essay that you've since disavowed, where those questions were both alive and unclear for you. Thinking of Julia's question about ambiguity and ambivalence, and also about art and contradiction, but taking it into the realm of the real-world scarcity around community representation, which, again, you've nodded to, is a different situation than 10 years ago around there isn’t a scarcity the same way, but talk to us about writing taboos and a little more about trans people behaving badly.

TP: I could only write Detransition, Baby because I wrote The Masker, which is the last novella in this. I still think that The Masker is the most dangerous, the most taboo politically thing that I've ever written. Not because it's so shocking, but because of the actual context, which is that, historically, basically, psychiatrists said that there are two types of trans people—or there's actually only one type of trans person, and then there's perverts. There are "true transsexuals," who are people who, if they were girls, played with dolls as little kids, wanted to marry men, and basically just lived their life identically to any cis woman. Then there were perverts, who got off on dressing up in panties and jerking off, and who became transsexuals because they'd essentially taken their perversion too far. This continues to be somewhat accepted in the psychiatric world. Meanwhile, all of the medicine that we get through insurance and things like that is predicated on the idea that we are all "real transsexuals" suffering from gender dysphoria. As a result, sexuality in any way that it manifests in being trans has been pushed to the side. When I was coming out, it was always like, "Well, there's sexuality, and there's gender, and the two are actually separate structures." People said that not because it was true or because that's what they felt, I think, but because admitting sexuality into it opened you up to a realm of psychiatry that would just say that you're a pervert. I mean, this is in the DSM. I don't think that's how it works. People's sexualities are like flashing markers for what they want and how they feel. If you want to live your life in a certain way, of course, it's going to show up in your sexuality. The more you repress it, the more that sexuality is going to come out in extreme ways because you've repressed it. So you have sissy culture or online forced feminization, where you want some powerful person to turn you into a woman. To me, that's a marker of the fact that you've repressed something, and maybe you need to look at yourself. I'm not saying if you read these stories, you are trans, but many people who do are trans. Meanwhile, these stories have been seized upon by TERFs and bigots to say that trans women aren't women, that they're perverts who just want to get off on women's clothing, objectify women, and break them down into component parts as fetish items to take for themselves. The Silence of the Lambs is probably a great example of this, where Buffalo Bill skins women and then dances around in a woman's suit he's made from women’s skins. This is out there, and it's the underlying reason why trans women get banned from bathrooms, why they’re like, "You can't be near women's locker rooms. You can't be near children," all these things, this idea that trans women are fetishizing women and taking their things for themselves. So The Masker basically, instead of rejecting this and saying, "No, that's not what's going on. We are actually very respectable people who have no sexuality whatsoever and are totally safe to have in your bathrooms and locker rooms," it says, again, "So what? So what if this is the case?" It's a story of a sissy who's shown two options. One is a trans woman who embodies a grotesque level of respectability, like a former cop in a bowling league, and the respectability is just repressing something else. Or you have somebody else, a female masker who wears a silicone full-body suit and is basically like, "Getting off on your gender is a superpower. Why would you ever transition when you can just dress up like a girl, feel incredibly turned on, and be in the pink fog?" The early transition or maybe very late pre-transition narrator has to choose between these two visions in a very claustrophobic way. Basically, what it’s saying is you can arrive at being trans through fetishistic stories, through fetish in general. It doesn't mean you're not trans if you come to it through fetish. That's very politically dangerous. In fact, I fully expect sections—and it has happened in the past—where people have found my old versions of The Masker and excerpted things, not attributed as fiction, but attributed to me, Torrey Peters, as saying, "Oh, I can get off on violence toward women," or whatever thing these confused characters say as they're trying to figure out their desires. This story has been used politically to basically say that trans women are dangerous. It will happen again. It absolutely will happen again by publishing this. But I feel that saying to people who are not transitioning, who are not living their lives because they think that they're a pervert or because they've internalized a lot of this stuff, that this doesn't mean you're a pervert, that actually, you can be free and live your life. Here's a story of somebody who is doing what you're doing now, and look how... let me portray it for you. Let me portray how sad and weird it looks to live in fear of being a pervert, and that that can free people through fiction, which is what fiction is. That's the dream, is to really free people with fiction. I think it’s worth it. I’m interested in that taboo. If I wrote a character who is perfect and great, that's not going to free anybody. Nobody's going to look at a perfect, great character and say, "Yeah, that's my struggle too. I'm also perfect and great." That’s not a hard thing to look at. I mean, you mentioned Philip Roth. Toni Morrison's first book, The Bluest Eye, I think, is another example of an incredibly dangerous book. A Black family where the father rapes the daughter, and the daughter's dream is to look white so she can be pretty. How dangerous was that? To show a character who's so internalized and start to basically say that whiteness is prettiness, and that Black men are dangerous to their children—this particular Black man, in this story, and basically being like, “This is actually the context of racism.” You can’t see how racism destroys minds and beautiful families if you just show them overcoming all the time. That’s not what it actually does. You can’t recognize that in our lives. To me, books like Philip Roth, like Toni Morrison, that’s the amazing thing fiction can do.

DN: Yeah, I think The Bluest Eye is a great comparison. When this book was announced, you described it as, "My evolving attempt to explore the emotional, lived questions at the murky edges of gender that can't be captured by identity categories; the places where we are just people yearning, crashing, loving and messing up." Again, a reiteration that you are not centering transition narratives, which makes me think about you screenwriting for the Detransition, Baby TV series, where you called making that book into a 30-minute comedy sitcom as feeling like the most subversive thing, perhaps similar to setting the book in the first place within the form of a bourgeois family novel, but I also suspect because it would be showing the dailiness of trans people living ordinary lives—going to work, coming home, sitting on the couch, having dinner. One thing you said in Michigan Quarterly Review about this adaptation, which I wanted to spend a moment with, is—and I’m partially paraphrasing here, so push back if I misspeak—that you feel like the past decades of arguments about trans representation are actually extremely cis, in so far as they focus on trans representation as if it relates to bodies. You say the controversies about cis people playing trans people in films and the demand that trans actors play trans parts is a regressive argument because it suggests that the only parts for trans people, ultimately, are playing other trans people. You suggest as a way to break out of this cycle that we have to consider that, “The idea that we’re going to look at a person’s body, we’re going to determine whether or not that body is trans, and then we’re going to slot it into roles, is actually not how trans people think of their own bodies. My body is in some ways, incidental to my experience. It’s very important, but it’s also like, If I did this surgery, and not that surgery, I don’t think it makes my body more or less trans. And yet the entire casting process is about the specificity of these bodies. And we have to have the right body for the right role. Well, my question is, how do you visually represent transness in a way that’s not all about bodies? Detransition, Baby is an interesting problem because the Ames character is a trans woman detransitioned. Do you hire a trans woman and then tell her to act like a man? Do you hire a man and then hire a separate trans-woman actor to play Amy” Amy being Ames before she transitioned. All in all, these conundrums and this proliferation of questions without answers seem to me that it delights you more than they vex you. But I wondered if it provoked any further thoughts hearing that back. Also, I'm curious if you have any news about the show, if it's going to get greenlit or not.

TP: No, it's not going to get greenlit. I'll just start with the bad news. It was at Amazon, and they fired all the executives post-Lord of the Rings debacle. They fired all the executives who had bought it and got rid of 95% of the shows in development. It went from a network that did things like Transparent and Underground Railroad to just Jack Reacher and NFL. So Detransition, Baby didn’t fit in with that. There were a bunch of other really, Patricia Lockwood had a show there. I am so sad that that show, it’s so funny, for myself I’m just like, “I want to see a Patricia Lockwood show.”

DN: Me too.

TP: I mean, the wordplay on that show must have been incredible. Yeah, so it's not going to happen. But it’s interesting, the actual solution that I came up with on that show was—this is before Taylor Swift was the biggest star in the world—but I wanted Taylor Swift to play Amy, the trans woman version of Ames. Not because Ames looks like Taylor Swift, but because Taylor Swift is sort of a dysphoric projection of Amy. In fact, when you're feeling dysphoria, when I’m feeling dysphoria and dysmorphia, when I don't know what my body looks like because I’m so in my head about it or have some sort of dysphoria or I’m vaguely dissociated, it happens to be last and last, but when I was younger, I would picture myself as somebody else to walk into a room, to basically be like, “I’m confident.” So Amy is picturing Taylor Swift to walk into a room every time, as a dysphoric projection where she’s like, "I'm Taylor Swift moving around the world, and I can do fine in the world." So we actually can't ever see Amy visually behind her dysphoric projection of herself, which means if Taylor Swift played Amy, viewers only ever see Taylor Swift, which is a cis body, or not, which [inaudible]. You could cast a cis woman to play a trans woman if you're talking about how it actually feels to be in a trans body instead of how it looks to be in a trans body. This is a problem for movies forever—the gaze. If you can move away from the gaze and be like, "What is it like for me to look at a cis woman, and do I enjoy it or not enjoy it?" which is often the operative question is in terms of the gaze, but instead basically be like, "That’s not actually what’s happening, I’m actually seeing what is being felt." Getting around this kind of thing was interesting to me. I wrote that in 2021, where she was a big, ungettable star. I was kind of like, what she’ll actually get as some smaller star to when the show was up for Amazon, which they literally told me, they were like, "Okay, now go get Taylor Swift." I was like, "What? What do you mean?" [laughter] They were like, "Yeah, well, you wrote the show for Taylor Swift." I was like, "No, I wrote it for an idea of someone like Taylor Swift." They were like, "Oh, just go call her." [laughter] And I had probably the most humiliating meeting of my life. It was just a phone call thing where my producer and I—she doesn’t have an agent, she has a music manager—I don’t know how we can pull this off, but we managed to get a phone call with her music manager. The executives were like, "We thought you [inaudible] Taylor Swift. So go get her, otherwise, you don’t get a show.” So we did it, get this meeting with [inaudible], we were basically like, “Yeah, we want Taylor Swift to play a trans woman who’s not actually a trans woman, but a projection of a trans woman, in a recurring role, but probably only two or three episodes. We don’t have much money for it. But, you know, what do you think?" [laughter] And they were like, "Um, well, we’ve got a billion-dollar music tour planned, so I think we don’t have the space for it." You could just hear the what the fuck. That’s sort of a synecdoche of my whole time in Hollywood, which is being put in vaguely humiliating positions to ask for outrageous things that I was never going to get because basically nobody understood what I was hoping to do anyway. When the show didn’t go on, I was obviously very sad but being able to be a novelist again where if I want Taylor Swift in my novel, I just write Taylor Swift and then write a disclaimer that says, “All characters are fictional.” [laughter] Much better way to go about during these kinds of things.

DN: Yeah. As much as we would have loved to have seen it. [laughter] Part of why I bring this up about bodies versus selves is because I think one of the things that makes your work distinct is your relationship to a different sort of backstory, not the backstory of your Strategic Opacity talk, not the backstory to explain a character's motivations to a cis reader or cis editor. But I think instead, I guess what I would call the backstory of former selves within what you call ongoing transition, that perhaps there isn't an arrival to a static place in your version of a transition narrative. But even if there is an arrival, former selves re-echo. Even if they didn't re-echo, it seems you don't want to disown these former selves. I think of the sports scene in Infect Your Friends at a trans beach pride event where the trans woman character feels self-conscious about playing sports because her body would re-assume “male poses,” and it feels like it's pointing to the way perhaps that even trans categories can be gender confining. But more, I felt—even though it's unspoken, and perhaps I'm imagining into this—but it felt like the story was posing a subtextual question, something like, “Why couldn't these so-called male poses be part of my identity as a trans woman?” Or maybe, “Why do these male poses, which echo a former self, have to be threats to my current self?” Or maybe, “If we are to portray authentic lived trans experiences, wouldn’t it involve portraying moments just like this?” In Vulture magazine, you talked about how you didn't know the word "trans" until you were an adult, that when you were in a Quaker boarding school in Iowa, you had a Facebook page as a boy and another as a girl. You've also talked about later on, when fully out as a trans woman, that at a particularly difficult point in your life, you felt like you needed to either figure out how to detransition and live as a man or find a way to have a baby as a trans woman and somehow legitimize womanhood this way. You didn't do either, but it's these in-between moments that are, I think, such a big part of these novellas and your novel. The Masker is dedicated, for instance, to my former self at her most afraid. But The Chaser and Stag Dance are also very much stories like this. In fact, those two are not even necessarily trans stories in the narrow sense of the word. They might be pre-transition stories, or intended as such, where characters are puzzling at how they are and how they want to be. But they might not be. They might be queer cis stories, and it feels indeterminate by design. It also seems like an open tent for lots of selves to be there at once. I wonder if this is true. I also wonder if this aspect is welcomed, celebrated, or ruffles feathers within trans discourse. I'd imagine perhaps all of the above, like in any community. But I think of how you said, for instance, that you like to use the dated term transsexual, which some people find offensive because it has a certain verb—it has a more '70s pulpy exploitation feel, whereas the acceptable transgender feels more like a medical term. To me, your invitation of all the selves, past and present, in these stories feels like this preference for transsexual, it feels feral and uncontainable in a way. I wondered, what does that bring up for you?