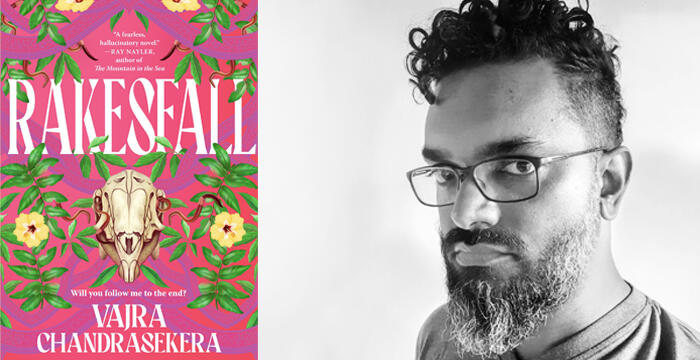

Vajra Chandrasekera : Rakesfall

Sri Lankan writer Vajra Chandrasekera’s first novel, The Saint of Bright Doors, was shortlisted for or won nearly every major SFF award there is. Much of the buzz around this book circled the question:”what exactly is this?” Saints not only didn’t fulfill the expected tropes of the genre, but seemed to be actively working against them, subverting them. Vajra’s new book Rakesfall, however, makes his debut, for all its innovation, seem normative by comparison. Rakesfall is set both in an ancient mythic past and a far distant post-human future, calling into question where the past and the future begin and end. Rakesfall is a book with two characters (or maybe one) who are constantly dying and being reborn, changing names, changing bodies, where it isn’t always clear who is who, or where self and other begin and end. Rakesfall is continually changing shape, style and form, with stories within stories within stories, a rabbit hole of stories, a wormhole of stories, where you are never sure you will ever resurface into the “real world” again. Of course, we talk about form and trope and genre, but we also talk at-length about Sri Lankan Buddhism and how, as a political force, it has woven its own story into a mythos of nation-state and race. And how this very storytelling has led to violence, from the everyday and bureaucratic to outright genocide. Vajra’s books can be engaged with and enjoyed without any knowledge of this, but the more we explore his own interrogations of Buddhist hegemony in Sri Lanka the more the subtext of his books feels central, the more his subversion of form and genre feels outright political. In one of his essays he asks ‘how do we write in a monstrous world?’ How do we write toward liberation, toward solidarity, whatever the odds? Today’s conversation provides one great example of just that.

For the bonus audio archive Vajra translates an excerpt of a story by an award-winning Sri Lankan writer, a writer who, when he posted this story on his Facebook page, was arrested and imprisoned under the accusation that the story was anti-Buddhist. Vajra translates this excerpt and reads it for us while also contextualizing why he thinks this story was seen as blasphemous. To learn how to subscribe to the bonus audio archive and the other potential benefits of joining the Between the Covers community as a listener-supporter head over to the show’s Patreon page.

Finally, here is today’s BookShop.

Transcript

David Naimon: Today's episode of Between the Covers is brought to you by All Lit Up, Canada's independent online bookstore and literary space for readers of emerging, quirky, and acclaimed indie books. All Lit Up is your Canadian connection for award-winning fiction and poetry, author interviews, book roundups, recommendations, and more. The only online retailer dedicated to Canadian literature, All Lit Up features books from 60 literary publishers and now they offer e-books in accessible formats through their ebooks for Everyone collection. All Lit Up makes it easy to discover and buy exciting contemporary Canadian literature all in one place. Check out www.alllitup.ca. US readers can also shop All Lit Up close to home and save on shipping when they purchase books from its Bookshop.org affiliate shop. Browse selected titles at bookshop.org/shop/alllitup. Today's episode is also brought to you by Cloud Missives, an intimate and dissecting poetry collection by Kenzie Allen. Like an anthropologist, Kenzie Allen reveals a life that arises from the ashes of tragedies and acts of perseverance, asking how one can reimagine indigenous personhood in the wake of colonialism and examining what healing might look like when you love the world around you. Craig Santos Perez calls Allen “an important voice in Native literature” and Diane Seuss states that Cloud Missives is a masterwork of self-reclamation and survival through love. Cloud Missives is out August 20th from Tin House and available for pre-order now. For today's conversation with Vajra Chandrasekera, my approach is a little bit different, or perhaps it's the same but an extreme version of it. Not only because both of his books work so outside received forms and tropes but also because there's a subtext to both of his books that is highly political, and grounded in lived reality that you don't need to know or even be that aware of to read his books and enjoy them but which form both the impulse and architecture for them. Before Vajra talks, I spend a chunk of time sharing the responses of others to his books to recreate the atmosphere of how they are being received. But most notably, because of the distinct, compelling, and also challenging qualities of his new book, we spend the first 75 minutes laying the groundwork so that we have a shared understanding of things outside the book that inform the book so that in the second half of the interview, we can really engage with Rakesfall in a deep way. Vajra’s working against genre, against trope, against received forms, is inseparable from the ways he's interrogating Sri Lankan Buddhist hegemony, the ways it has woven its own story into national and racial myth-making and power at the expense of people who are non-Buddhist and/or non-Sinhalese. While you don't need to know any of this at all to enjoy his two books, understanding this element only enriches one's reading. Our look into the ways Sri Lankan Buddhism tells the story of itself, and by extension, the way storytelling and mytho-historical fantasy storytelling can lead to violence from the small and every day and bureaucratic to outright genocide connect to many of the past conversations on the show, not just conversations that have interrogated the most idealized versions of a given religion in relation to the embodied reality of it but yes, those as well. Part two of my conversation with Naomi Klein, the conversation with Pádraig Ó Tuama, and the conversation with Charif Shanahan do that respectively with the three Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The conversation with Vauhini Vara looks in part at the pluralistic vision of the Indian Constitution, whose chief architect was the Dalit Intellectual Ambedkar versus the Hindu-centric and supremacist movement in power today. But I don't think this is particular to religions but rather to storytelling, the stories we infuse into the word democracy, secular humanism, or citizen, the goodwill we automatically bestow on these words while committing unspeakable violences or erasures in their name. The power of story to facilitate these erasures links many past conversations on Between the Covers, all the way to the conversation with Karen Joy Fowler where we look at the qualities we give to the word human that have actually prevented legitimate science that actually has shown that these qualities aren't exclusively human at all. All this to say, our extended examination of Buddhism is both very much about Buddhism as it is in the world versus its idealized form but also as Vajra himself says today, it's about much more. It's about all of us, any of us living in the postcolonial world under late capitalism. In that spirit, Vajra's contribution to the bonus audio archive is a special one. In 2019, an award-winning Sri Lankan writer posted a story on his Facebook page and was subsequently arrested and imprisoned for it, for having written a story perceived as anti-Buddhist. Vajra not only talks about what he sees as the three so-called blasphemies in the story and talks about the fate of this writer, he also translates the third blasphemy for us, a brief story within the story, a subversion of a classical tale and reads his translation of it for the bonus audio. To find out how to subscribe to the bonus audio archive and about the many other potential benefits and rewards of joining the Between the Covers Community as a listener-supporter, everything from rare collectibles to the Tin House Early Reader subscription, you can check it all out at patreon.com/betweenthecovers. Now, for today's conversation with none other than Vajra Chandrasekera.

[Intro]

David Naimon: Good morning and welcome to Between the Covers. I'm David Naimon, your host. Today's guest is Sri Lankan writer Vajra Chandrasekera. Vajra's debut novel, The Saint of Bright Doors, came out last year and has been a topic of conversation ever since. Nominated for the Lambda Literary Award and LGBTQ+ Speculative Fiction, it's a finalist for the The Subjective Chaos Kind of Award for best fantasy novel, the Hugo Award for Best Novel, and the 2024 Ursula K. Le Guin Award for Fiction, as well as the winner of the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, William L. Crawford Fantasy Award given to a writer for a first fantasy book whose past winners include past guests on the show Carmen Maria Machado and Sofia Samatar. The Saint of Bright Doors is the 2023 winner of the Nebula Award for Best Novel and the 2024 Locus Award for Best First Novel. It's also a 2023 New York Times Notable Book and the sci-fi fantasy columnist for the New York Times, Amal El-Mohtar, called it the best book she read all year, “Protean, singular, original. I can’t remember the last time a book made me so excited about its existence, its casual challenge to what a fantasy novel could be.” Jake Casella at Locus Magazine adds, “Books that are good to mediocre, but entertaining or idea-filled, are easy to talk about. Books that are troubling or problematic are easy to talk about. Even badly written books, if they’re entertaining or problematic, are easy to talk about. Truly superb books – ones that are complete, that are organic, that invite themselves into your brain fully formed and transport you somewhere else, that leave you humming and staring and obsessed, that leave characters and images and ideas hard-printed among your own memories – are hard to talk about. It’s hard to talk about Vajra Chandrasekera’s The Saint of Bright Doors.” Molly Templeton at Tor.com says, “How can a single 400-page novel have between its covers so many ideas that every time I think about it, I want to pick it up again? It’s rare—and wonderful—to read a novel that feels at once utterly of another world and entirely of our own, a heady brew of the intimate and wild and wise and questioning. It’s the kind of book that might just change the way you read.” Prior to his first novel, Chandrasekera was a longstanding prolific writer in the short form with over 100 published short stories, essays, and reviews, appearing in many of the most noteworthy science fiction and fantasy magazines, from Clarkesworld to Analog to Uncanny. He was also fiction editor at Strange Horizons during the stretch when Strange Horizons was, for six consecutive years, a finalist for the Hugo Award for Best Semiprozine, when it won the British Fantasy Award for Best magazine, and when it won the Ignyte Community Award for Outstanding Efforts in Service of Inclusion and Equitable Practice in Genre. He's also the editor of the upcoming anthology Afterlives: The Year's Best Death Stories. The arrival of Vajra's second novel, Rakesfall, the one we're talking about today, a year after The Saint of Bright Doors burst on the scene, comes with a ton of built-in anticipation. MahaRaj at Dragonmount says, “For readers who seek the union of philosophical and political arguments that can reference the Hindu epic Ramayana, the Sri Lankan Civil War, and post-human cyberpunk detective stories, this is your book.” Library Journal in its starred review says, “Chandrasekera challenges readers but rewards them with a breathtaking narrative that invokes sci-fi, fantasy, and myth to express the endless struggle of revolution.” Finally, Premee Mohamed says, “Luminous, wrenching, intense — Rakesfall left me breathless…. If this is not considered a work of genius, we have lost the meaning of the word.” Welcome to Between the Covers, Vajra Chandrasekera.

Vajra Chandrasekera: Thank you so much for having me.

DN: I want to spend some time exploring some of the questions your first book raises as a way to prepare us to discuss Rakesfall, especially because some of the things that are true about your first book are an order of magnitude more true about your second. Saints was mainly met with thunderous critical acclaim but also at the same time, with a much smaller number of equally passionate people who were dissenters with the book, a recent focus for instance on a popular podcast that roasts books, what these two camps have in common is a sense of, “What the f*ck” or “What is this?” The larger group is thrilled by this experience. The smaller group is put off by it. Here are some examples from people who were at the same time both bewildered and full of admiration. Past Between the Covers guest and great reviewer of genre books Jo Walton said, “The experience of reading The Saint of Bright Doors is a little like having a mild fever. Everything is slightly too big and too bright, and details keep piling up and slipping out of control. Stunning. I am still a little stunned by it myself.” Dan Hartland of Ancillary Review of Books said, “The novel expresses a deep distrust of SFF’s singular heroes, refuses to adopt or clarify its magical system (itself wielded almost exclusively by the novel’s primary antagonist); and, wherever one detects in the prose an influence—Jeff VanderMeer here, Nalo Hopkinson there—the novel turns almost immediately away from it, hurtling unexpectedly in quite another direction. It does not merely subvert expectations, but undoes them, dismantling the very generic frameworks with which we at first presumed it was playing. What’s remarkable is how entertaining this radicalism proves.” On Twitter, you speak about how the less positive critiques are often complaining about loose ends or dropped threads where you say this critique reads to you like a kind of induced anhedonia and you lament the way we've standardized how we engage with art, bringing up what you call “ending explained culture and apps that give people 15-minute summaries of any book so we don't have to read them.” All of which you say feels like watching coral reefs bleach in real time. Contrast this to The New York Times reviewer Amal El-Mohtar, who is also bewildered saying, “As a critic I often attempt to turn myself into a book’s ideal reader in order to do it justice. It’s bewildering to encounter a book for which I am, in fact, already the ideal reader, a book that gives me everything I didn’t know I needed, that makes me feel both the pinwheeling fall from climbing a step that isn’t there, and the relief of being caught before I hit the ground.” So I was hoping we could start here and hear more about what you think is going on with this bipolar response to your work, what you think it is in your work that provokes it, and any other thoughts this conjures in you as sort of an entryway into your two books.

VC: Well, hearing all this at one go is quite overwhelming because many people have been extremely kind and generous about this book, and very articulate I must say. All of these people do a better job of describing the book than I do myself, which is not uncommon, writers struggle with describing their own books. I think the divisiveness insofar as there are two camps broadly but I think that's actually gotten worse with Rakesfall for predictable reasons, is a very long-standing divide, especially between the part of the genre that wanted it to push its boundaries. I think this goes back to the 70s with the British New Wave and the writers in the States as well, like Delany and [inaudible]. Again, I think about 20 years ago with the New Weird, which I've always thought of as the same divide, Christopher Priest called it slipstream in the 90s and John Harrison called it the New Weird in the 2000s. It's essentially the divide between people who think of writing genre fiction as prose first, as a kind of literature who think of it as, I think Delany called it a paraliterature. But what he meant was it's the kind of literature that exists outside the boundaries of, especially then, what was considered literature. But there's also a very strong camp of genre fiction that believes it should be pure entertainment, pure escapism, and that it's preferable to be trope-heavy, to be driven by these recognizable prefabricated components that prefer the vast territories of genre fiction that are in fact produced in exactly that way and doesn't like to see, I guess, the literary influences of other kinds of fiction creeping in, the divide that's been in place for much longer than I've been writing, for much longer than I've been alive, so I'm very happy to be part of it in a way. [laughs] I think for me, my encounter with genre fiction, with science fiction fantasy is a little peculiar because I'm from Sri Lanka and I was, for the most part, not reading what was contemporary when I was growing up. I was reading older works because those are the books that were available to me in the ‘80s and ‘90s in Colombo. So I was reading '60s and '70s novels when I was growing up for the most part and rapidly caught up in the late '90s when those books started to arrive when, for example, Clarke Award winner started to arrive in the British Council Library in Colombo. I had a very compressed history of the latter half of the 20th century and genre fiction landed on me in the ‘90s. I inhaled it all at once rather than seeing it play out over decades. This left me with a strange take on what I preferred in genre, what kind of works I like to read. Obviously, the things that stood out to me more were the prose-forward kind of stories. I think I came away with the idea that is very opposed to the way that a lot of writers think about science fiction and fantasy books, about world building, about plot. I don't think about any of those things in the way that is currently most fashionable. I tend to think of fiction as it is on the page, as sentences, as paragraphs. I don't think in terms of characters moving around in a world rather and so much is about sentences moving on the page. I think this is one of the big differences and one of the big disconnects for a lot of people is that it's a kind of book, both books [inaudible] more than Saint. But even the Saint, it’s a kind of book that it's hard to read with one eye closed. [laughter]

DN: Well, you've started to answer or maybe you've answered my next question but I'm going to ask it, just to press on this just for another moment. I start our conversation in this weird way because this discourse around your books begs the question around your relationship to form and genre with both of your books, so I'd love to hear a little more about your relationship to it. For instance, one admiring reviewer wondered why the book was published as fantasy with Tor versus, say, post-colonial literature at Knopf. You've talked about how you wanted it published a genre because in your words, as a writer from the third world with no money, no degrees, and no prestige workshops on your CV, a writer who had never visited the first world and had no contexts there, you felt there were more gaps in the fence around genre than around the world of literary fiction. I'd also suspect that your long-standing activity as an editor and short story writer in the genre world might have made you more familiar with how that world operates too. But putting aside the practical decision of where you thought you could get your foot in the door, do you have any hope or desire around through what lens the readers would ideally read the work? Or is that beside the point? Is that for the reader to ultimately come up with?

VC: Partly it is but I do love speculative fiction. I always have. I enjoy the freedom it gives. I don't just mean the freedom of being able to have anything happen in the text. The freedom I think is also a kind of freedom from a particular kind of path as a writer. I don't know how accurate this was but 10, 15 years ago when I was thinking about publishing, I felt very constrained by the literary parts as a literary writer that I could see for myself in Sri Lanka, I felt it was almost obligatory to write a certain kind of novel, the postcolonial novel, following several generations of a family through decolonization and how you cope with modernity, I don't know if this is the kind of book I ended up writing. Anyway, it just so happens to be in a fantasy frame. But that was the strong impression I had of literary fiction at that age and at that time, and that much less exposure to publishing in the West. In hindsight, I think I could probably have made it work either way. But at the time, genre, fiction in general felt much more freeing. There seemed to be less expectations of seriousness. There's a kind of dreadful gravitas that seems to be expected of the postcolonial literary writer, which I think is not actually true in reality but that is the impression one gets. Many of the books are much more fun and whimsical than you might guess from some of the covers for example. But there's a dreariness to it. My work is very playful in a lot of ways, which I think also does not necessarily come across from some of the descriptions of it. I like to make jokes. I like to make stupid puns. I like the kind of free willing world of genre, magazines as well which is a much more accessible world in a lot of ways than for example the literary fiction magazine world is heavily dominated by US universities, university magazines, I mean I have published a few of those as well but it does require a certain familiarity with a form or a culture. I think ideally, you would be a closer part of that culture. It would be attending the readings. I'd really be attending, in fact, one of those universities, doing a master's in finance or whatever. There is a culture there that I felt very far away from whereas genre fiction has always felt very unhindered, very open to experiment, to failure even. It felt much more acceptable to bullsh*t, to write some wacky story, send it somewhere, maybe even get it published without any great consequence. It felt like a safer space for me to experiment and that's how I started out. Then I rapidly began to get more ambitious in that frame as well. But it felt like a space that was more accessible also because genre magazines, even the smaller ones tend to pay whereas if you want to get paid by literary fiction magazines, you have to sell to the bigger ones, which is harder if you're not already a well-known name in those circles. Genre magazines do pay.

DN: That really speaks to me to a more functioning literary economy too, the fandom of genre magazines. People subscribe to the magazines. The readers are participating in the support of the magazines in a real bidirectional way so that the writers are getting professional rates whereas a lot of these magazines you're talking about that are, say, university-run, you might get into an extremely prestigious magazine in terms of how often it gets cited or anthologized but very few people are actually reading the work in the magazine. It gets shelved in a university library, then there it goes into the ether.

VC: Yeah, Strange Horizons, for example, has been funding itself for 20-odd years now. I think they just concluded the most recent fund drive. It's entirely reader-supported. Every year, they raise all the money they need to pay all the writers, artists, and other contributors. I think many other magazines operate similarly. Of course, we could have more readers. [laughter] Many of the magazines are still struggling.

DN: Sure.

VC: But I think it's insofar as magazine ecosystems go, it's certainly one of the healthier ones.

DN: Yeah.

VC: Over the last 15 years or so, we have seen a lot of Asian and African writers appearing in those magazines for this very reason.

DN: Well, I really like what Dan Hartland suggested about you working against genre, working against the notion of the hero, working against the norms and tropes that people expect in both sci-fi and fantasy. Because on the level of theme and on the level of story, both your books are engaging with questions of liberation and revolution. Hartland's suggestion is that you're also doing this on the level of form. In both books, there are countless times where you make me have to confront what I was expecting by not delivering it. But I also wondered if you weren't just writing against form but perhaps we're also writing within forms that I didn't know or didn't know well. For instance, I wondered if there were Sri Lankan or South Asian modes, forms, or shapes of storytelling that you might be not working against but within that would also contribute to a sense of something new to a North American reader. If there was something here formally in that regard, I would love to hear about it. But either way, I'd also love to hear about how you've spoken about wanting this to work for two discrete audiences at the same time. You said on The Coode Street Podcast that you wanted it to work fully on the genre level so that a reader doesn't have to know anything about or catch any of the illusions that are Sri Lankan-specific, sort of like when you read Dune where you don't have to understand the real world allegorical elements to fully engage with the book or the movies but you also wanted it to work on a political level where it engaged with the political history in Sri Lanka for those who know about it or who want to learn about it. Talk to us about any Sri Lankan storytelling tropes that are being employed if there are some but also how you navigate this balancing act of satisfying two different readers on different terms.

VC: I wouldn't say that there were any particular Sri Lankan tropes in play here. Actually, if anything, I think censorship is the major trope of Sri Lankan literature in the post-globalism and specifically religious censorship, the inability that many writers have faced in voicing even the mildest critiques or jokes at the expense of Buddhism. In terms of the two layers as it were, the two audiences, it's a tough line to walk and I spend a lot of time practicing that with short fiction because I rapidly realized that when I would write a short story and publish it, I would get very different responses from American audiences and Sri Lankan audiences. For example, my Twitter following would be roughly equally divided between the two of them. I would publish a short story that one audience would see as a fantasy and the other audience would say as political commentary and also a fantasy. So I got used to navigating that and not having to require readers to move to the other side of that line. I feel like it should be possible for people to encounter works and not feel like they have to go read background material. I don't want to be homework. It's also I think a very practical necessity when you're a third-world writer trying to build a career in the first, is that you can't do that, especially if you're a genre writer. When you're a genre writer, you're supposed to be a commercial writer. You're not framed by the publishing industry or by the critical establishment as, “Oh, here is a Sri Lankan writer who you can read.” For example, Shehan Karunatilaka's book The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, which is a great book, I enjoy Shehan's book very much. I liked his first book even more, which is a cricket book and I can see why that didn't take off outside the cricket-speaking world. [laughter] But I think the way that a book like that under the ages of The Booker Prize is the way it's promoted to people is very much, “Okay, here's a book through which you can understand Sri Lanka and Sri Lanka's history,” which is possible because that's something that I think literary fiction does well of us badly, depending on your perspective on representation, on the necessities of representation or being even boxed into representation. Whereas in commercial fiction, in genre fiction, the line is a little fuzzier. I think for the most part, it's about, “Is this book enjoyable? Is this fun? Is this entertaining? Are people intrigued enough about it to talk about it?” But not necessarily, “What are we learning about Sri Lanka from this text?” Well, a lot of readers do react to it that way, which I think is a perfectly reasonable way to react to that text. But I could not assume that people would come to this text with the frame that, “Okay, I am now going to access Sri Lanka through this text,” which if it was published by somebody else might have been the framing. But with the genre publisher, that's not how it worked. With the genre publisher, it's very much, “Oh, he has a fantasy novel about this person who has these very magical encounters and mystical appearances,” and so forth. It's all a question of framing. I think I've successfully managed to at least say with Rakesfall, I've blurred that line and made some of the extrusions into each other's territory explicit. There are sections explicitly set in Sri Lanka, directly talking about Sri Lankan history and politics, which I have no idea how that's going to land, the book has only been out for a month. Maybe people will react negatively to that but I think it's the balancing act that I'm never entirely sure is working. I think it's a balancing act that also goes away. People often say that they want to reread these books. I think if you reread them, this whole entire question of framing will rapidly become irrelevant because the more you look closely at it, the more things become obvious.

DN: Yeah, I'm a perfect example of this. I think one perfect example in The Saint of Bright Doors that shows the parallel possibilities of reading where you could stay on one track or you could decide to leap over is with the protagonist Fetter. Fetter is raised by his mother with a chosen fate, with her training her son to be an assassin. But not any assassin but training him to kill his own father, the leader of a powerful religious political group who calls him The Perfect and Kind. As an aside, one of the hilarious ways you undermine the hero narrative, both the notion of chosenness and destiny in this book, is to have him, early on in the narrative, refuse his calling, move to a city as a nobody, and to join a support group for others like him, people who are also now unchosen. Essentially, he's doing group therapy with failed prophets and messianic castoffs. But more on point, when I read this book, I read this entirely as I just stated it and it works entirely as such. There were many other elements of the book where I could feel the book touching the real world more directly. But I thought here that this dynamic was more oblique and perhaps less specific. But then in preparing for today, I discovered one reviewer and actually only one who mentions that the English translation of the Buddha's son's name or Siddhārtha's son's name before he's the Buddha is itself Fetter because his son, Siddhārtha's son, is a fetter. He's a tether that would potentially prevent his own enlightenment, just as it's true in your novel. But at least for me, knowing that the subtext of these choices is that Fetter is being raised and trained essentially to assassinate the analog in your book, in your world of the future Buddha or the Buddha deeply changes the reading for me. What seemed oblique all of a sudden seemed central. Not that the other reading wasn't both engaging, it was and also completely valid on its own terms. Both of your books are critiques of not just Buddhist hegemony and the war crimes and genocide committed by Buddhists in Sri Lanka but at least in part, they also engage with aspects of Buddhism as well. I'd love to spend some time with these elements of the book that we don't need to know about but which enrich our reading if we happen to know about. Perhaps a place to start is with something you mentioned in your essay Unbhuddhism. You were prompted to write this essay after a Sri Lankan politician said, “I am not a Buddhist but I am influenced by Buddhist philosophy and thought.” How these appeals to a pure Buddhism, a Buddhism abstracted from time and place, is a common move to distance oneself from what is being done in Buddhism's name. You say in response, “Looking for the pure and uncorrupted heart is how hell is made.” Talk to us about the notion of the perfect and the kind or the pure and uncorrupted in this light and how you grapple with it in your writing.

VC: I have spent many years finding different ways to articulate my critique of Sri Lankan Buddhism, which is in a way, it's what all my fiction is about and most of my non-fiction as well for that matter. I started writing in the aftermath of the genocide in 2009. Among other things, that was one of the reasons I decided to do something else with my life. [laughs] The Unbhuddhism essay was predictably very polarizing to a Sri Lankan audience as are many of the things that I say in general about Buddhism. But I think these are things that need to be said because Sri Lankan Buddhism, since the Buddhist revival of the late 19th century, Sri Lankan Buddhism, in its modern form, essentially bears no relationship to whatever romanticized view of ancient Buddhism that we or anybody else might have. What we have and have had for 140, 150 years now is a very xenophobic, a very nationalist, a very deeply racist, violent, and highly politically organized and manipulative institution in the sense that we have this establishment of monks who are very much part of electoral politics. They have their own parties or actually, they have an active one right now but they have had multiple such groups that are various Buddhist-themed fascist groups essentially, like enacting physical violence on minorities at the street level. At the high level of politics, you have these senior monk figures who provide them with ideological cover. Part of this is this exact same maneuver, this appeal to purity. For example, there is a particular monk called Gnanasara who has been in the news in Sri Lanka many, many times and has been arrested also for violence many times, who is a canonical example of the classic modern Sri Lankan monk who is violent, racist, xenophobic, violent both physically and verbally, and at the heart of many social clashes and crises. So there has been a lot of public criticism of this man and many others like him. Yet when push comes to shove, this is the senior council of Mahanayaka, the most senior body of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, which is a council of four senior monks, essentially, the Pope of Sri Lankan Buddhism put out a statement saying, I'm paraphrasing but essentially it was, “While we don't necessarily condone his attitude, nevertheless, he is a monk and he is correct.” That is the line. That is how this plays out. There is a mild finger wagging at the rowdy behavior of these fellows. But in the end, the establishment protects itself and Gnanasara himself said something very telling I think which is one time, after he had been charged in court with something, he had a press conference professing great sorrow of having been accused of the violence he was committing. He said something on the lines of, “I'm giving all this up to pursue Nirvana, to meditate and be whatever, whatever.” Then a few days later, possibly a week later, he had another press conference and said, “No, I've decided against it because people appeal to me so much. Nirvana can wait because I have to be politically engaged in the moment,” returning to fascism on the street. This maneuver has been the main rhetorical maneuver of Sri Lankan Buddhism since at least the 1940s, which is that the spiritual pursuits of Buddhism are good, noble and represent the reason why Buddhism must be protected but they are also not to be used. They are to be put away for a future day when you have time for such things as spiritual pursuits. Because in the present day, it is much more urgent to set minorities’ houses on fire and burn down their libraries and so forth. This is very maneuverable find in the conversation in the discourse of every bourgeois singular Buddhist person from the 1940s through to the modern day which is like, “Oh, well, I'm not a very good Buddhist and neither are the monks frankly but Buddhism itself is pure and needs to be protected.” You will find this language in Myanmar. You will find this language from the Dalai Lama. Buddhism is prone to this failure, this ethical failure of putting aside its own professed ethical purity in order to act politically in the world today, often ostensibly in the defense of the Buddhism that is pure, which has been put away. Violence is acceptable and the Dalai Lama himself actually didn't say this in interview, which the monks in Myanmar used to justify their genocide, which is that you can accept violence in the defense of Buddhism because Buddhism is too pure and too valuable to be destroyed. If something threatens Buddhism, you must destroy it. That is a version of Buddhism that is the most common, the version of Theravada Buddhism that is most common in the world today as far as I can tell, and the version that I think is very important to critique because I think, especially in the West, people have a very romanticized version of Buddhism in their heads going back to, I don't know, The Beatles possibly, like the hippie idea of Buddhism as, “Oh, the peaceful religion, the one that isn't like all the other violent,” which is, “No, no, Buddhism is just like everyone else.” Arguably worse because a lot of things are happening under the cover of this professed facade of peacefulness.

DN: I want to actually speak directly to this Western projection onto Buddhism. But first, in that same essay on Buddhism, I'm going to just quote a couple things you said, which you've already articulated but I just get a joy out of reading the barbed critique and the humor that you use in critiquing. So you say in that essay, “It is the standard rhetorical maneuver by which Buddhists declare themselves above normative Buddhist ethics. Buddhist ethics is valuable, they say, because, e.g., it forbids killing, therefore killing is justified to preserve those ethics. Buddhist ethics are like the good China, the fancy heirloom teapot you have in the glass cabinet for visitors to admire, but you are definitely not going to serve tea out of it.” It's in that essay where you quote the Dalai Lama, just to be more specific about what he said, it was somewhat of a thought exercise. If there were only one living person who practiced Buddhist teachings in the world, he would be okay with the killing of people to protect the living embodiment of the final person practicing Buddhism. But you could have just as easily quoted the head of Myanmar's Buddhist nationalist 969 Movement, whose Buddhist monk leader has said, “You can be full of kindness and love, but you cannot sleep next to a mad dog.” By the mad dog, he's referring to the Muslim population of Myanmar. This sense of inherent goodness works as a way to not see and contend with what one is doing and/or as a means to get others to not be able to. For instance, you were tweeting in response—and I'm sure the politics of this is mainly lost on me—but you were tweeting in response to a recent photo of an activist monk in Sri Lanka being served biryani where the original post by another said, “Have a look at this picture if you want to get an idea how hilarious our national harmony and unity are. Serving biryani to the one who is opposed to singing the National Anthem in Tamil,” then you say, speaking of his Buddhist clerical dress, “The robe just splatters unearned moral authority around, just absolutely spilling it in buckets over a bunch of men who couldn't find their own asses with a map and a flashlight, then they go out into the world and do stupid shit and everybody else has to clean it up.” I bring this up partly because I have a personal interest in this. I grew up with a lot of exposure to Buddhism I think compared to most Americans. As an aside, I'll just say that I'm interested in Buddhism and there's a lot that I find compelling in it. While you have declared yourself an un-Buddhist, you grew up as someone considered Buddhist within the context of racialized religious groups in Sri Lanka and you do write about aspects you find meaningful as well within your larger rejection of it as an organizing principle for yourself. But American Buddhism is already by nature, as you've just alluded to, abstracted from an embodied cultural context and attractive to people for its abstract elements, which would make the notion of Buddhist fascism, as you talk about it, or Buddhist terror, as Time magazine described Myanmar's 969 Movement, particularly shocking to just an average American seeking spiritual insight. My hometown Boulder has the only Buddhist university in the United States, Naropa University. It was founded by a Tibetan Buddhist, Chögyam Trungpa, whose umbrella organization is Shambhala International. He asked Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, Diane di Prima, and John Cage to set up the poetry department at Naropa in the 70s. This beat poet countercultural aspect of Buddhism was very much a part of my growing up as was Allen Ginsberg's presence in my city. Trungpa coined this term crazy wisdom and there were a lot of “free love,” teachers and gurus sleeping with innumerable students. But the robes, to use your words, seemed to splatter unearned moral authority around with allegations of sexual and physical abuse of pedophilia, and rape from Trungpa's time up until the contemporary moment in the Shambhala organization. The most notorious, being Trungpa’s appointed successor as lineage holder, testing HIV positive and continuing to have unprotected sex with students, men and women, without informing them of his status because he believed that as long as he kept up his Buddhist practice, the Dharma would protect him from transmitting the virus. This was something the board of Shambhala knew about for multiple years without doing anything, a belief that led to multiple people being infected and a person dying. As much as it seems like I'm going really far astray from your books, I do think this is deeply relevant to your writing, especially thinking about the ways fantasy can prevent people from seeing the material results of their actions in the world. So I wonder if we could spend a moment talking about the Sri Lankan flag, which with its 5-1-1 pattern, one might at first glance see this as enshrining the validity of the presence of minorities within the image of the country, and by extension, in the country, but how it's actually obscuring, how those demographic proportions were arrived at and how they're maintained. A flag that you've said, in all its iterations, is both fascist and racist. And the ways, in your meditation on it, you look at fantasy and storytelling with regards to all the elements in the flag, both this proportionality but also the image of the lion. Because it feels here, like if we go back to Dan Hartland, I think he's hitting something true, that you are working against tropes. So there's a real power in this fantasy trope and storytelling is very powerful. When you talk about censorship in Sri Lanka, people are concerned about words. Talk to us a little bit as another entryway into the worlds you're creating the story that's embedded in the flag.

VC: You've read my essay The Red Flag, I believe.

DN: Yes, I have.

VC: The lion is part of our national mythology for multiple reasons, right? One is that the Sinha Le, the majority demographic, a majoritiness that was achieved mostly through violence incidentally, the Sinha Le means the lion people or the blood of the lion, something like that. There's an origin story, a mythic origin story about our ancestor, and actually I tell a version of this in The Saint of Bright Doors, except in The Saint of Bright Doors, it's a leopard for reasons. [laughs] The myth is that there is a monstrous lion who meets with a human princess and has a half-lion son whose own son is the originator of the “Sinha Le race.” There's a lot of 19th century scientific racist thought that is alive and well today in Sri Lanka and in the world at large, obviously because this is the world that was built and handed down to us and the world that we're all grappling with. But this idea of the Sinha Le race, so for example, you're probably familiar with the replacement theory in the West.

DN: Yes.

VC: The white race is being replaced with. In Sri Lanka, we have literally our own version of it, a Sinha Le version of it, which is all the Tamil people or the Muslim people are an ethnic group rather than a religious group in Sri Lanka, also for entirely arbitrary reasons, that these minorities will replace the Sinha Les and we will lose our strange and wondrous island, etc. Replacement theory is exactly the same ideological device wherever it goes. It's agnostic as to who inherits the mantle of whiteness. It's just the detritus of the empire. You have it one way over there. We have it one way over here. The lion became I think initially, and this happened a lot with both Buddhism and with the land, these anti-colonial symbols, like you say anti-colonial symbols, anti-colonial ideologies and you're inclined to support those things because that sounds like a good thing, right? You're opposing the empire. It is a good thing in a sense insofar as you are opposing the empire. But unfortunately, Sri Lanka's anti-colonial thinking ideology in the late 19th century was very racist from the very beginning because this flag was designed in conjunction with legislation that disenfranchised some 700,000, 800,000 Tamil people in 1947, just on the cusp of decolonization. While there are many justifications for this, none of them are reasonable obviously, this is fundamentally about how during colonial era politics, what little representational politics that the native people had in the colonial government was divided by racial lines according to census categories that were themselves determined by the colonial British government. Basically, they divided the people of this island up into categories, categories that they kept reshuffling for a while, and by the time the 1940s came around, they had settled on a set and political power was divided, was allocated based on those groups, and which meant that demographic power literally translated into political power. There was a political incentive to disenfranchise a vast population of the largest minority so as to prevent that group from becoming a serious threat to single hegemony in the first decade of independence. That is literally reflected in how the red, the orange, and the green flag are not tricolor. It could have been a tricolor, like with equal bars of colors but no. Instead, it's distorted specifically to highlight demographic supremacy. It's like, “Oh, no, the red is bigger,” but this is a singular country. On the side here, you have these minority groups who are tolerated.

DN: Would it be correct to say that it's anti-colonial in regards to Britain? And it's an extension of colonization with regards to the other groups that are non-Sinhalese Buddhist.

VC: Very much so. That is the operation that I think I've spent a lot of time writing about and talking about as well because I think it's something that gets lost a lot in Sri Lankan discourse. We're very proud of having escaped the empire, which everyone should be proud of. It was very bad. But the way it was done set up the decades that would follow because that independence began in these hugely racist xenophobic acts like in the post-colonial nation with language restrictions, the Sinhala Only Act of 956, the Citizenship Act of 47. At the very moment of independence, these huge steps were being taken to disenfranchise and repress the Tamil minority primary, to reduce the numbers, to reduce their access to education. This played out over the decades to come. Obviously, it led to the war. The war equally inexorably, given the entrenchedness of these political positions and these ideologies, led to the genocide. It all unravels from that in a way that is both deeply, horrifically predictable and in the sense that it would all have been avoidable if people had been better, obviously, but they were not. Those are leadership problems, yes, the problems of ideology I think more than anything else because there were ideological critiques within the “Sinha Le camp,” obviously the racialization is false but the racialization is what produces this political culture, so you can't talk about it without racialization. There was an idealistic critique that needed to happen in the ‘40s and ‘50s and it did not happen. In fact, what did happen was that the Buddhist establishment, the monks from Walpola Rahula Thero onwards, specifically made the wrong move to politicize the priesthood and to politicize it towards nationalism. There's no actual reason why Buddhism should be associated with Sinha Le people. Many of the Great Buddhist scholars of the pre-colonial past were Tamil or what we would today call Tamil. South India was one of the Great Buddhists centers of learning in those centuries. If anything, Buddhism is more Tamil than Sinhalese, yet somehow, this is where we are today. Buddhism is thoroughly violently identified with Sinha Le culture. I'm sorry, I've drifted very far from the point. I feel like I'm ranting.

DN: [Laughter] Well, okay, so we have a question for you from another. But as a way to set it up and preface it, I'm going to read a very often quoted line from The Saint of Bright Doors, then I was hoping you would read something from Rakesfall. There's one line that's often quoted in your first book and it's advice of Fetter's mother to her assassin's son. The quote is, “The only way to change the world is through intentional, directed violence.” In Rakesfall, there's a parable called The Simile Of The Two-Handled Saw that I was hoping you could read for us as a way to introduce a question that's going to come from another.

VC: Sure. I'd be happy to. Incidentally, The Simile Of The Two-Handled Saw is a real Buddhist parable.

DN: Oh, really?

VC: Yeah, it's my translation.

DN: I had no idea.

VC: It is. I forget the actual name but it's in the sutras. It doesn't mention the secret police that was me. [laughter] But other than that, it's real. [laughter]

[Vajra Chandrasekera reads from Rakesfall]

DN: We’ve been listening to Vajra Chandrasekera read from Rakesfall. Okay, so we have a question for you from Gautam Bhatia. He's a constitutional lawyer in India. He's the author of Offend, Shock, Or Disturb: Free Speech Under the Indian Constitution and The Transformative Constitution: A Radical Biography in Nine Acts. He's also a sci-fi writer, the author of the novels The Wall, and its sequel, The Horizon. He's an editor at one of the best sci-fi fantasy magazines, Strange Horizons. Here's the question for you from him.

Gautam Bhatia: Hi, Vajra, Gautam here. I'm interested in the way in which your books approach the granularity of power and the way bureaucratic violence is so central to the larger project of state violence, and how that might stem from quite a singular South Asian experience of the way violence is meted out and often decentralized and outsourced by the state.

VC: I’m very happy to hear from Gautam. We’re old colleagues from Strange Horizons. That's a great question. It is one of the curious things about The Saint of Bright Doors that I think a lot of readers have seen in reviews and so forth. People read it as a warning against authoritarian states, which is fine, but authoritarian states that are far away. Other people's authoritarian state over there in Sri Lanka, it's like this and yes, certainly very much over there in Sri Lanka, it is like this and in India too. But I think part of what I was trying to say is that it is like this everywhere. This is the state, the state that we have, that we all inherit under late capitalist modernity. We're all post-colonial, whether we're a former colony or not because the empire was everywhere. The same tools, the tools that are used to press dissent in the metropole were field-tested in the colony. They are to this day field tested in the new colony. The death politic of bureaucracy and racialized bureaucracy is something that operates the same way everywhere, just the labels are different but the mechanisms are the same. I think the granularity of the kind of authoritarianism talking about the kind of state control, the kind of the deep-seated historical operations of the kind of power I'm talking about are granular at far more levels than I think most people care to think about. Racialization is one of them. Something like a censorship law versus a category of census racialization operates at such different levels that one seems normal and the other seems like oppression but they're actually both oppression in much the same way. None of this is like a novel though. I think all this was written about, like in critical theory, 50 years ago if not more. But we don't often consider and we certainly don't consider enough the ways in which we are taught to oppress ourselves. The authoritative state does not go around beating us with sticks into doing what it wants. It gives us the stick and says, “Now, beat yourself,” and we do. That is what we are taught in our schools. That is how we are taught at work. That is what we are taught in our temples, in our churches. That is what we are made to do to each other all the time. I think it's easier to see these things in a fantasy world because you can blow them up and make them larger than life. You can turn them into these bizarre things. For example, in Luriat, the city of The Saint of Bright Doors, there are two competing constitutions and two competing supreme courts. But if you think about it, this is generally true in every two-party democracy. It's just that they just do not separate, that they just happen to occupy the same space. The struggle of one overcoming the other is part of the narrative of our democracies. The applicability of laws, the differential applicability of laws by class, by caste, by race, is another way in which these things go unremarked by people whose privilege protects them from noticing that power is in operation. There are certain things that, and I write about this in Rakesfall for example, the way my name or the character’s name but in that case, it's the same as mine, would protect someone from a police checkpoint and that someone whose name was very nearly the same, except for one spare consonant, would not be protected and that is not a written law. That is an unwritten law but it is an invisible power operating on the world and on the people. That is what I'm talking about when I say the invisible laws and powers of the world are devils because these monstrous operations of the world are both hidden from us and also extremely evident.

DN: Well, the reason why I wanted to place this exchange about violence here right after our discussion about the rhetorical move to save an abstracted pure Buddhism from what Buddhists are doing in the world is that there has been writing about how you portray violence that suggests you're working intentionally to make that rhetorical move impossible in your worlds. That the violence in your world is baked into the substrate to the most mundane elements of the world itself, just as it is in the “real world” as you've just explained really well, like the way a census could be an act of violence. Gautam in his writing about you talks about how much of Anglo-American fantasy is produced in societies that have been, relatively speaking, stable where their authors often have to reach back into an imagined distant past, either feudal or medieval, and often portray the violence as set-piece battles. Whereas your work not only has the urgency of trying to capture the essence of a moment before it becomes history but also, unlike overt battles, it evokes violence in its more granular everyday bureaucratic form. Tehnuka at Strange Horizons talks about how all the violence you do portray, both that of the everyday caste hierarchies and racism to actual riots/pogroms, that they are all deeply embedded in the setting itself. This, to me, seems like your great counterpoint to the impulse to try to abstract from or transcend the political context to a pure idealized state, that violence, to borrow a phrase from Christina Sharpe, is the weather. I wondered if that rang true for you. I feel like you've already nodded in that direction, I mean because this isn't unique to Buddhism, I mean obviously, we're very aware in the West of the dissonance between the figure of Jesus and all of the popes who signed the papal decrees to allow the discoverers to go around the world and commit genocide across the Americas. But does this ring true to you in a way, the way you're writing your story, the way violence is everywhere, including these invisible devils, the mechanisms of just the way we live, then are forced to beat ourselves, is that in a way in response to or a remedy against this move to try to leap away to a transcendent space?

VC: I think so. I try not to shy away from depicting the violence but I try to not foreground it also because I think like in fantasy and science fiction also, in general, there's an expectation of heroic fight scenes and I don't have any. In fact, the continual frustration of the anticipated heroic fight scene is one of the things that people find irritating about The Saint of Bright Doors. [laughter] Because I set up Fetter to be, he's allegedly good at fighting but he never actually fights. Insofar as he gets into fights, he always loses, sometimes quite dangerously, which I think is most people's experience with violence in general, is that it's everywhere and it's not pretty. But I don't think it's true that Western fantasy doesn't talk about contemporary. You just have to find works that isn't in that medieval fantasy mode because there's a lot of contemporary settings in fantasy talking about police violence, for example, which I think is one of the dominant concerns of our time. There's plenty of South Asian fantasy looking into the past, most often in a very heroic mode and in some cases, in outright fascist modes like the Hindutva fantasy which is popular in India. So it's not that fantasy in any place or any style is capable of addressing anything, any particular kind of violence, or articulating a particular critique of violence. I think it's just a question of what people choose to do with the tools that they take up. It is true that I am trying to sabotage this rhetorical maneuver. They appeal to a purer Buddhism or purer ethics that is not being used by coupling them tightly rather than decoupling them, which is the standard maneuver, and showing as best as I can, how the violence actually derives from those ethics, those purported clean or pure ethics themselves contain, in my opinion, the seeds of the violence. At first, it seems hypocritical because you're saying, “Oh, there's a good thing and then I'm doing bad things to protect it, but I'm not partaking in the good thing.” What I'm saying is that the problem is actually deeper than that, which is that there is no good thing to begin with. There are good things in Buddhism, certainly. There are many parts of Buddhist philosophy or thought that I find intriguing. I wrote about this in the Buddhism essay as well. There's a ton of Buddhist thinking in my work and the way I think in general. But as a political-religious institution, I think the way that this so-called Buddhist ethics has been articulated into politics, and this is not even just a modern thing, but going back to the medieval or pre-medieval era, the way that Buddhism has always made itself comfortable with power, with thrones, has always had these seeds of violence, because it is very much product of its time and place, just as a lot of like older systems are. Those are things that, I think, if a system of thought or belief is to remain concurrent, then these things must be critiqued and worked through in the present day. They have not been in Sri Lankan Buddhism. In theory, what the Buddhism in general has, I think, just classified certain things. It's like, “Oh, these are unchangeable ideas and we don't touch them. Those are pure Buddhism that we have to protect.” But, for example, and a lot of this is actually directly in the [inaudible] the disgust of the body, the subtle disdain for other body and consequent denial of the meaningfulness of bodily suffering. There are contradictions here that should lead to a critique of the way of the purity itself that is being held up for us. There are several layers of how Buddhism preach generally, both in the original law and in the present day. I don’t know if I’ve written about this. I don’t know if this is relevant. But there was an article about female Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka complaining about mistreatment by misogynist male Buddhist monks. That's perfectly accurate and true, and they're right to complain about it. But in the process of complaining about this, they also told the interviewer that no one in the history of Sri Lanka, in modern Sri Lanka has suffered as they have suffered. I'm sorry, you're like, you're singular Buddhist monks, men or women, you're one of the most privileged classes in this country. This is intersectionality in action, literally. There are many critiques that simply do not happen, those kinds of comments go unaddressed and uncontested because there’s no one with the moral authority to contest it in this environment. The way in which that any critique of Buddhism is faultlessly interpreted as insult, as blasphemy, as warranting state violence in response is another one of these things. Buddhism itself famously is open to critique of itself. It is something that you will find, even your average Buddhist monk will say as much. But then if you actually articulate a critique, they don't respond to it the way that they're supposed to, because what they mean is that critiques can be articulated, but no critique can be articulated because the system is perfect. It is so perfect that it allows critique of itself. But if you were to articulate a critique, then the system would not be perfect, and that's an insult, right? [laughter]

DN: Yeah, that's amazing. Okay, so this, for sure in my 14 years of doing this, this is the longest I've ever waited in an interview to fully jump into a book and what a book is about. But I do have a logic for it as Rakesfall is even harder to summarize or categorize or describe than Saints. So much so that it makes Saints seem linear and a walk in the park in comparison, which it is not. Aware of this, you've been posting negative Goodreads reviews like “a bunch of jumbled nonsense that would have done better as poetry.” But on the flip side, it's been called “an evocative epic poem of a novel” and is generating a ton of enthusiasm. For example, Christina Orlando, at Reactor. Like, “Chandrasekara could be writing about traffic lights changing color, and I would read it and be fucking riveted. It is shocking to me that this man is not a poet. He is a poet. Anyways, Rakesfall is a story within story, within story, a tale of reincarnation, and entangled souls.” Sia at Every Book a Doorway, says, There is a murder-mystery; there are many attempts to ‘regreen’ the Earth after climate collapse; there is identity-theft with souls; there are quests, kind of; Who is it for? Anyone who craves layers and layers of thought and myth and meaning in their fiction, who wants to sink their teeth into a Rôti sans pareil of a book and feel it bite back.” You've said it took you a while to know how to describe your debut to others, that it took time and practice. I imagine Rakesfall even more so, but I heard you recently do it really well. Imagine we're in an elevator together, Vajra, and I turned to you and go, “What's your book about?” [laughter] Introduce us to Rakesfall.

VC: Lately, I've been calling Rakesfall a genre-dysphoric story. It follows two people as they recur or reincarnate across history, across different worlds, different pasts, presents, futures, from the mythic past to modern Sri Lanka to a far future Earth that has been abandoned by most of humanity. The relationship between these two people changes as they change and as the story changes. Sometimes as the same person. They become entangled in the politics of every world they encounter and they cause trouble wherever they go. They always seem to betray each other and one of them always dies, but they have to keep finding each other again and again anyway. Rakesfall is about how power is always accompanied by resistance, no matter how imperial and totalizing that power might be. It's about how wherever you go, you'll find a throne that needs to be overthrown.

DN: That's great. Well, you've talked about Kim Stanley Robinson's The Years of Rice and Salt as an influence, but that Robinson played reincarnation straight. You're not only enacting it, but you're critiquing it. One reviewer called the book “Hindu monistic philosophy in a Marxist critical, theoretic frame.” I can understand why he might say Hindu insofar as the book engages with epics from India and also, in my rudimentary understanding of reincarnation, one difference between Hindu and Buddhist reincarnation is that in Hindu reincarnation, there's a continuity of self across lives, and there is no eternal self in Buddhism. Similarly in your book, even though chapter to chapter, where the protagonists are in different times with different names, and sometimes we don't know who is who, or even if they're actually two separate beings at all, there is a continuity of sorts. But at the same time, it's hard for me to believe that you're critiquing Hinduism and not Buddhism here. So talk to us about your critique of reincarnation, both what form of reincarnation, if there is a form in specific you're critiquing and the substance of the critique that you see yourself enacting in Rakesfall.

VC: It's actually quite strange for me because I grew up in a reincarnation normative culture. In the world I grew up in, reincarnation was understood to be the norm in much in the way that, I guess, like, heaven is taken fairly literally in a Christian community, reincarnation was considered just one of those things, just like how things are. The way that reincarnation is understood in Orthodox, like everyday practice in modern Sri Lanka, is very different from the abstract, philosophical version of it that you might, for example, like as a continuity of souls is not only assumed but it is gamified. [laughter]

DN: Really?

VC: Like all funerary rituals, for example—there's a scene about this in Rakesfall as well—about transmitting what we call merit or it's kind of like good vibes basically, but good vibes that are like currency in the world of rebirth, of reincarnation. If you have a lot of merit, you get a good rebirth. If you don't have a lot of merit, you get a bad rebirth as an animal or a demon, whatever. Your ethics and your whole worldview is about collecting these chips. You do good deeds in order to collect merit in order to be guaranteed of a future good life in your next life and the lives after that and so on and so forth. It is generally considered very gosh at best to aspire to Nirvana in Theravada Buddhism. We don't do that around here. [laughter] That's some like nonsense, my honest like shit. No, we understand that Nirvana is very hard and it takes like a billion lifetimes and it's super difficult and only really special can do it anyway, and you think you're special or something. So for us, it's really about just making sure you have access to the good life in the next life by being good in the next. Consequently, that means people who are experiencing the good life in this life have been good in past lives. For example, if you're beautiful or rich, that means you deserve it. If you're poor, disabled, or suffering, you also deserve it. Basically, this whole model is basically a giant “fuck you” to most people. [laughter] That is the system I am trying to critique here. [laughter] I have literally sat through like a billion sermons as a child, where some monk was trying to explain why poor people deserve it and how if you're very good, and give lots of alms to monks in this life, you'll probably be rich in your next life. This is really compatible with capitalism, our present president in fact attempted to make that connection explicit in one of his ghostwritten books but it didn't take off. I'm surprised it hasn't taken off more. I believe we have various cults trying to do exactly this. Soon or later it will take off, then we'll have the equivalent of, what do you call it, the Christian version of this, the evangelical version of this.

DN: Oh, the prosperity gospel.

VC: Prosperity gospel. We were like five seconds away from a Buddhist prosperity gospel, and no one has quite managed to hit the exact right note yet, but all the ingredients are there. What I wanted to say is that my version of reincarnation is horizontal, the idea that we are all moving through time together. In a very material way, we die, we decompose, we are reconstituted as future people. In a more classic Buddhistic way, I don't actually believe in the individual soul or in a collective one for that matter. But the idea that I think that Rakesfall taps into critiquing itself as it was by the end is that people are not all that very different across space and time. People are people. That is part of what I mean when I say that power is always accompanied by resistance. There are always power-hungry people. There are always people who see that and say, “No, we're not going to stand for that.” I think those fundamental attitudes and personalities are what recur through time and we inspire each other into that through our art. Art is one of the anchors of the kind of reincarnation I'm talking about is that, James Baldwin said this I think, you think no one has felt like you do in all of time and then you read.

DN: Yeah, that's a great line.

VC: Yeah, it's a great line. I think that to me, that's what reincarnation means, is that we are inspiring, connecting, and infecting each other across space and time. That, rather than the soul, is what I anchor this idea in. Even though the tagline for the story about two souls following each other really is about resonance, the resonance between different people in different places and times, who the idea that people are fundamentally drawing from the same worlds, building themselves from the same paths, and that this is how we find echoes of ourselves in time, which is also, I think, to me what solidarity means in the sweep of like history.

DN: Well, much like each chapter places our two “characters” in different settings and eras with different names, different bodies, and more, each section is written in a different style, whether in the form of a play, a parable, or murder mystery, whether in the genre of fantasy or more decidedly science fictional, the pair are being reincarnated in different forms but so are the chapters. But as if that were not enough, the stories are often nested with stories embedded in stories. You've talked about your long-standing love of stories within stories. You open Rakesfall with this aspect in a particularly extreme and foregrounded way, perhaps suggesting how we should read the book as a whole. We open the book with our two protagonists on TV, so within a show, but there's also a show within that show called The Documentary, a show that itself is about fandom. There's the notion that the two main characters who we follow throughout the book will emerge from the show into the real world. There are four factions of fans who differ with regards to how this will occur. The two main ones being that they would either become fully possessed by their characters or emerge as new flesh as physical duplicates of the actors but independent of them. So talk to us about the opening to the book, why it's important that the book begins here, and more about your [inaudible] method of storytelling in Rakesfall.

VC: I do love stories within stories. I especially love, and I think this also happens at some point in all the nesting stories within stories, but then not coming all the way out again, which I find particularly delightful and no doubt many people find intensely annoying. The first chapter of the first section of Rakesfall is Peristalsis. I published that originally as a short story because it seemed to me that it felt complete enough in itself at that time, or I could publish this as a short story. We begin the story with two kids looking at a screen, watching something else. Then watching a show that is essentially watching, looking back at us, and that's the framing to take throughout this whole book, which is that it's a story about stories, the story of stories, and it's very much about the people who are watching, which is the people who are watching are the fandom, but the fandom is also the dead, specifically the dead of genocide and of the wall. Many of these different sections of Rakesfall are different articulations of our or the character's relationship with the dead. There's one section where you have the living dead in a somewhat unconventional zombie story. You have these deserted haunted earths where the main character is haunted by the ghost of a destroyed world. You have this world where the elite dead have become a kind of haunting, mirroring, the original one. So different articulations of the idea of haunting, which is essentially the relationship between the living and the dead. Are they the grieving or are they the guilty? We move between both of those positions, the grief and the guilt. You could just easily say that Rakesfall is a book about grief and guilt, which I think is inevitable in anything that starts off as a story being watched by the ghosts of the dead.

DN: Well, to add another wrinkle to Rakesfall’s challenge to questions of identity over time, the two main characters are named Annelid and Leveret at the beginning. The first is the word for a segmented worm, the second comes from the French for rabbit. So we could look at this pairing as death and life as decomposition and fertility. You do underscore this with the first section being called Peristalsis, and with the lines, “We believe Leveret and Annelid are living matter, pushing themselves through a dying narrative until they breach the veil and emerge screaming, where we could see them as much traveling through a cosmic colon as we do through time and space.” But I want to spend some time with this question of time. The show in the opening section has no name, no credits, it has content that never ends without true episodes or seasons. You yourself have described the book as follows: “Rakesfall is science fiction for people who like their science fiction slippery and worryingly over-extended, like a very long worm that you’re pulling out of a hat, and you keep pulling and pulling but somehow there’s always more worm.” There's a line in the book spoken by a grandchild to a grandmother, “You mean that histories are true and stories are lies?” “No, both are true and both are lies,” grandmother says. “The difference is that stories have endings and histories understand that nothing ever ends.” So thinking of this, I wonder if Rakesfall, a book that spans from the deep mythic past to the time the earth is swallowed by the sun, a book that is spilling over in stories, is actually trying to be more like history than story in this setup, insofar as nothing ever ends in this book. It makes me think a little of your revival of the term science fantasy to describe your writing. It's a term that reminds me of when Kim Stanley Robinson was on the show where he was talking about Le Guin's so-called science fiction, which for him he felt was more like fantasy in space. You say science fantasy suggests that science fiction and fantasy are actually the same imaginative act, separated mostly by how they think about science, but in both cases, scientific thinking exists. But what particularly interests you about science fantasy and what I'm about to quote from you feels like a great description of Rakesfall itself and also an interesting commentary on time or on deep time. So you said, “For me, what's most interesting about science fantasy is that it likes to create these transpositions between the two genres that it bridges, as a way to demonstrate their ultimate non-duality. Like, for example, the far future and the far past, what if these things were the same thing? You're in a setting that seems like the far past to you but it actually turns out to be the extreme far future where technology is magic and magic is technology. What is the difference between a fantasy monster that's scientifically explicable versus an alien that's logically incomprehensible? At some level, they're the same thing, right? This pits reality as objective and knowable and practical, something that you can grasp against reality that's shifting and unreliable and uneasy. Even when you invent other worlds, they are in some fundamental way the same as our world rather than purely imaginary, worlds that are actually another way of looking at our own world.” So this is my long, almost never-ending way to ask you to talk about the never-endingness aspect of your book, about time and story versus time in history, or anything else that this field of thought provokes for you.