A War on All Fronts: Chris Santiago’s Small Wars Manual, the Future of Poetry, and the Casualties of A.I.

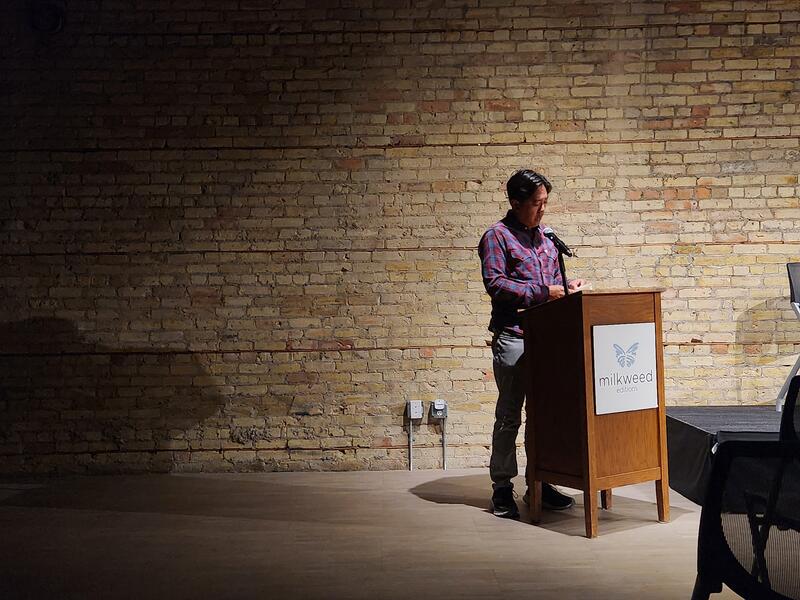

As we pass the perihelion of National Poetry Month, Milkweed Editions celebrated the launch of Chris Santiago’s newest poetry collection, Small Wars Manual, on April 16th. There, he was joined by poets that have each tackled small wars of their own: Kathryn Nuernberger, MC Hyland, and Rebecca Lehmann. Between the four of them—they alchemized militant warfare with poetry, prose, and shared community.

Around the room, poetry peeks from purses and palms. Signed copies curl into the crooks of elbows. In honor of National Poetry Month, poets from around the world strike pen to paper, writing a poem each day. All around us, it seems, poetry can’t help but pour from the planet.

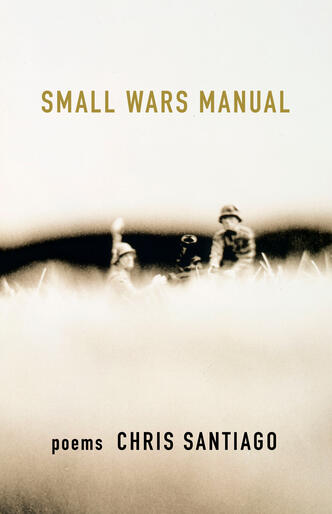

With his release of Small Wars Manual, Chris joins this outpouring by erasing the blueprints of war until only the truth remains. “Refugees,” he begins, “stream onto vessels / into asylum centers / unable to parse / the local language / or the difference / between the deported / and the departed.” When he turns the pages to us, it is a battlefield of blotted lines and crossed-out chapters. “This collection is an act of erasure,” he explains, “which is the reconstruction of new sentences taken from pre-existing documents.”

In this case, the pre-existing document is the 1940 manual of the same name, written to trace the military operations of the Philippine-American war. Though the war itself ceased at the tail-end of the nineteenth century, its shadows would permeate nearly every war after.

Transfixed by this repurposing, the crowd clutches tighter in the realization that all wars—both past and present—hold remnants of one another. Here, he thumbs through his book, chuckling. “I’m realizing these are mostly… grim poems,” he admits. We can’t help but laugh at his realization, releasing a collective breath we didn’t know we’d been holding. “Poetry can shift into bibliomancy, its own form of magic to divine the future.”

“Poetry can shift into bibliomancy, its own form of magic to divine the future.”

Following Chris, Kathryn Nuernberger alights the stage in frenetic flutter and rapid spitfire. With a sweeping gesture, she presents her poetry collection The Witch of Eye before letting it fall to the podium with a thud. “I was a bad grant recipient,” she admits, her voice a stage-whisper. For her grant research, she’d been deep into cricket research, spinning poetry from the threads of science. “By the end of it, I think I knew more about jellyfish, not crickets.” Like Chris, she draws on her own small war in justifying grant funds to meeting figures in the department of defense. “When you accept awards, you sometimes find yourself in unexpected company,” she delves, describing a walk she’d taken with a fellow recipient. “I fielded questions about crickets all afternoon. What about you, what do you do?” She countered. ‘I work in the Department of Defense,’ the man admitted. “The Department of Defense?” She laughs. “Why are we talking about crickets?”

Next, MC Hyland rises, offering a teasing quip before launching into her reading: “I’m sensing a bit of a tone, here.” Though her appearance is bubbly—her hair a perfect pincushion bun, a red scarf coiling around her neck—her voice is deadpan sarcasm and delightfully dry humor. In her collection, The Dead & The Living & the Bridge, her voice shifts into a form of alchemy to unite life and death. Between Kathryn’s scientific research and Chris’ erasure, she strikes a neutral zone of her own. In her reading, however, nature is at stark odds with the casual violence of military presence. “While my family played iSpy, I counted the army convoys that passed us.”

Closing the night, Rebecca Lehmann reads from her newest book, The Sweating Sickness, revealing the war for women’s rights in the overturning of Roe V. Wade. “I thought to myself, maybe they’ll reverse the decision once they realize how upset we are?” From battleplans on a global scale to the wars waged on women’s bodies, her response resonates with the battalion of poets behind her. By the end of her reading, her last line is an explosive, rhythmic refrain that encompasses heartache, rage, and mourning felt from the government level to the immediate community around us.

In the conversation after, they confront another kind of war altogether—one in which poetry falls under the siege of A.I. “Strangely enough,” Chris starts, “my book is the first Milkweed title to feature an artificial intelligence protection disclaimer,” he says, taking a moment to read it out loud. “No portion of this book may be used for or reproduced for the training of Artificial Intelligence.” For Milkweed, Small Wars Manual represents a furtive foray in protecting poets from A.I. “It’s an environmental crime, too,” MC Hyland adds, “not just a disaster.” Kathryn nods, joining in to confirm their feelings on the landscape of A.I and writing. “As you can probably tell,” she says, her laughter sardonic, “we’re not in a very good mood.”

For Chris, he can easily envision A.I. blending into our workflow. “A.I. is likely here to stay. Even if it strips creators from their jobs, remaining workers will be tasked with overseeing employees made of code.” MC Hyland, the least perturbed by A.I.’s impact on poetry, offers us a steadfast reminder. “Sure,” she laughs, “I’m worried about how it’ll change our thought patterns and how it destroys jobs, but not so much as a threat to poetry. It’s already a failed commodity.” Here, the crowd breaks into necessary laughter, a balm to balance the anger. “It’s true!” Kathryn adds, “the future of poetry is in its uselessness.” Chris shrugs and nods. “Uselessness might even be its greatest defense.”

True to his explanation on bibliomancy, Chris spirits the performance hall into an impromptu war-room, inviting audience members to dream their own defenses against A.I. “What comes next?” a young writer in the crowd asks, showing glimmers of a new generation already preparing for the next fight. “What happens if A.I. steals from books with an Artificial Intelligence Protective clause?” In his answer, Chris is sincere in his acknowledgement of the unknown territory ahead of us. “That’s such a large question, not just for poets, but for publishers, too. Everyone in the literary landscape will have to come together, to decide what happens next.”

Though this war isn’t small, we are ready to chart new strategies to protect writers against A.I.—if only to lessen the casualties of A.I. for future generations of poets and artists to come.