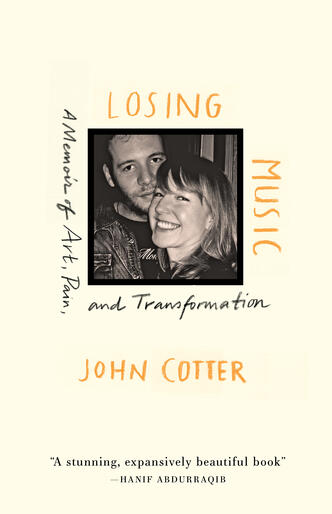

An Interview with John Cotter author of Losing Music

We are so very pleased to present this interview with Losing Music author, John Cotter. Losing Music is a vulnerable memoir that tracks John Cotter’s experience with “Ménière’s Disease.” It is a memoir that covers a wide breath of the human experience and we wanted to give John a chance to tell us more about it in his own words. We hope you enjoy!

Milkweed Staff (MS): Much of this book tracks your journey trying to find the correct diagnosis. What did that journey look like?

John Cotter (JC): Beginning around 2008 I started to lose my hearing and balance. I suffered vertigo attacks that left me unsteady for days. I couldn’t make the ringing in my head go away. Around 2012 that ringing turned into a roar so loud I couldn’t hear voices in loud rooms and then I couldn’t hear voices in quiet rooms. The vertigo became more frequent—I couldn’t drive and then I had to quit teaching and then I wasn’t physically able to get out of bed. This lasted a little over two years before it started—mysteriously and very gradually—to abate, leaving me mostly deaf. I saw doctors at Yale, Mayo Clinic, LA’s House Ear institute etc. I was diagnosed with bilateral Ménière’s disease, but I learned in the course of writing Losing Music that “Ménière’s Disease” doesn’t really signify—it’s a catch-all for untreatable ear trouble, no matter how mild or how dire.

MS: Losing Music covers more than just your medical journey and experiences. What else can be found between these pages?

JC: Readers of the book–perhaps to their surprise–will learn about how 18th century author Jonathan Swift experienced exactly the same symptoms. In the course of writing the book I researched his life and traced how the disease had affected him, and how it wound up influencing Gulliver’s Travels. In attempts to understand bad luck & trauma (& how one results in the other) I went to live and work in a remote homeless shelter in eastern Colorado and while there had a series of strange revelations. There’s also a good deal of material in the book about the history of hearing-assisted devices, sound dynamics, and adapting to familiar environments that have been changed beyond recognition. There’s material in the book about the difficulty of directing a play or teaching a class while you’re unpredictably going deaf. Since the condition never entirely resolved—I still hear that roar all the time, I still wear hearing aids—the book is a story about resolving to go on despite adversity, despite being a self attacked by the self. It’s a story about one kind of life changing into another kind of life, and about a person changing beyond recognition.

MS: Your evolution as a writer is an interesting one that informs the voice of the book. How did you make your way to becoming a writer?

JC: When I was an actor, when I was young, I did something very unusual (and probably unhelpful) and auditioned for plays with monologues I wrote myself. I dreamed of one day becoming a professional monologist like Anna Deavere Smith or Eric Bogosian. After getting my head taken apart in Bill Knott’s poetry class the monologues turned into poems and I performed for years in the Boston spoken word scene and then gradually learned to write for the page, publishing in the poetry magazines of the early ‘00s (Volt, Coconut). At some point I quit writing poetry and started writing prose. I published a short novel called Under the Small Lights with Miami University press in 2010. Around that time I founded an arts-review site and published some art criticism and book criticism. For about four or five years I was too sick and too unsettled to write—Losing Music is about that period of time. Around 2015 I published the essay “Losing Music.” It more-or-less went viral and my friends encouraged me to turn it into a book.