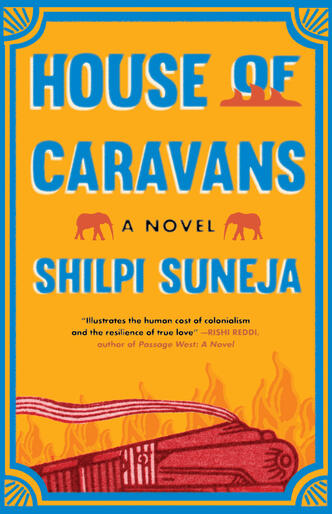

An interview with Shilpi Suneja about the inspiration behind her novel House of Caravans

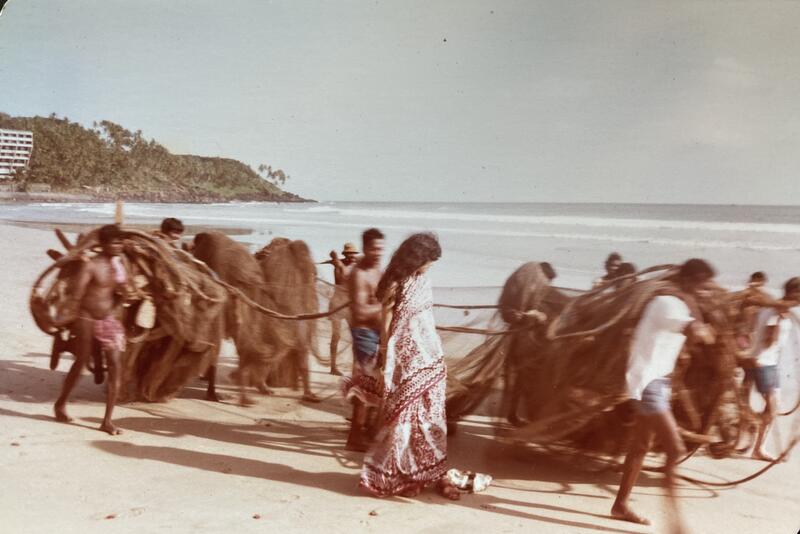

Shilpi Suneja’s mother in Goa on her honeymoon.

Shilpi Suneja’s debut novel House of Caravans is filled with life and intrigue as one family navigates post-Partition India and the many complicated dynamics that are left in the wake of political turmoil. Suneja shared with Milkweed Staff the personal stories that inspired the novel as well as the importance of Partition novels to the American literary dialectic.

Milkweed Staff (MS): The family in House of Caravans in so many ways is a microcosmic embodiment of many of the larger political and cultural tensions that have divided many post-Partition. Why write about a family when exploring these tensions?

Shilpi Suneja (SS): I suppose I wrote about a family because this is my first novel, and I believe family is how we first understand the world. Family is how I understood I was poorer than my cousins in America but a smidgeon wealthier than some of my cousins in Old Delhi. Family is also one of the earliest ways by which we understand big political upheavals. I remember during the 1992 Muslim pogrom when my hometown was under a shoot-at-sight curfew, my dad disappeared for several hours. My parents had a terrible marriage, so this was yet another instance of my father abandoning us. But then that same night, he reappeared terrified, contrite, bearing a clay pot full of steaming goat curry. The newspapers those days were full of grainy pictures of the people murdered in the streets. I vaguely remember the images, but I can never forget the taste of that goat curry–oddly metallic and full of heat, fear, and relief. For this novel, I channeled those fears. I did extensive research, read about the Partition as widely as I could, consulted British colonial economic policies, historical narratives, architectural histories of north Indian cities, and oral histories. But to convey an emotional history of the events–and this is exactly what I believe a novel is–I channeled the emotions through sibling rivalries, failed marriages, secret love affairs.

MS: House of Caravans takes place in a post 9/11 India and spans the stories of several generations of the same family. Why choose this time period as the one to focus on when telling this multigenerational story?

SS: As I understand it, 9/11 wasn’t simply America’s grievance, it became a collective, global hurt, what with massive arrests and deportations of Muslim youth and the culture of islamophobia. 9/11 made thematic sense to the story I wanted to tell about the long shadow of the 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent. The economic, religio-political and emotional instability caused by Partition, by the severing of familial, economic, cultural and linguistic ties (just to name a few) put power into the hands of a certain group of people. In place of a region replete with syncretic cultures and shared economic interests, the 1947 Partition birthed competing armies into being. That’s one definition of a nation–a political entity with an army. An army watches out only for the interest of the nation that funds it. Partition also birthed borders and boundaries with their calculus of passport and visa restrictions and the bitterness that denied visa applications inspire. Experts can weigh in on the Taliban and who funded them, but as a novelist I believe that one political grievance births another and another. I see a link between the Partition and 9/11. If there were no Pakistan–just like there were no India the way we understand it today–and no Bangladesh, how would the region function today economically, culturally, geopolitically? What would its diaspora look like? A lot of liberal South Asian scholars ask these questions.

MS: Why should American readers care about the Partition?

SS: While the book is set largely in South Asia with a brief interlude in Jackson Heights, NYC, I believe the story is relevant to our modern time and to America. What happens in one region of the world doesn’t stay isolated. Borders hitchhike on an army’s back. Freedom and also fight songs flow through the barrel of a gun. That and also this: immigrants bring cultural baggage and collective social memories. We shape America with our prejudices. Telling the stories of our former lives will only enrich our understanding of our present.

MS: Were any aspects of this book inspired by your own family history?

SS: The genesis of this novel lies in my grandfather’s journey from Lahore, Pakistan to Kanpur, India. I grew up listening to stories of how his family owned a flourishing dry fruits store and a boutique where he fitted khaki uniforms on English army-walas. As a child I dreamed about these stores, the noise in the bazaars, the language (Urdu) in the ledgers. It was a lot of fun researching and inventing all these little details–historical fiction is such fun to write! There are other aspects of this book that were inspired by true events. For example, my aunts and uncles grew up disliking an uncle. I’ve no idea who this person was or what he’d done to earn their mistrust, but that general sense of dislike had ballooned into a being over the years, so this nameless uncle became a central character in the book. My mom’s terrible marriage also forced its way into the book (how could it not?). This book is really a collection of all the big and little fears and curiosities I’ve held inside my body for a very long time.

MS: What makes House of Caravans different from all other Partition novels? How does it add to Partition literature? How do you situate this book in Parul’s Sehgal’s 2022 New Yorker essay?

SS: I love Parul Sehgal’s New Yorker essay: she names all the greats: Sadat Hasan Manto’s obsession with the shocking absurdity of division, Bapsi Sidhwa’s (published by Milkweed) bildungsroman that reads like the opposite of a bildungsroman. I believe there is room for other kinds of Partition stories, ones that examine its long shadow and find in it the roots of our current political grievances, such as the rise of religious fascism and Hindu nationalism. This unbroken link is what I hope my novel brings to the genre of Partition literature.

MS: What do you hope readers will come away with after reading House of Caravans?

SS: I hope this book tells a story worth finishing. I hope readers find in it a nuanced portrayal of colonialism, two nations’ independence, and of division. Through it I hope they see just how complex the whole apparatus of human wants and needs becomes at a time when no decision and no action can stand on its own like a beacon of moral compunction. I hope they find in it a rambunctious family, some hope, and a lot of heartbreak, because heartbreak is a kind teacher.