Changing the Game: Graphic Designers on Keith S. Wilson's Games for Children

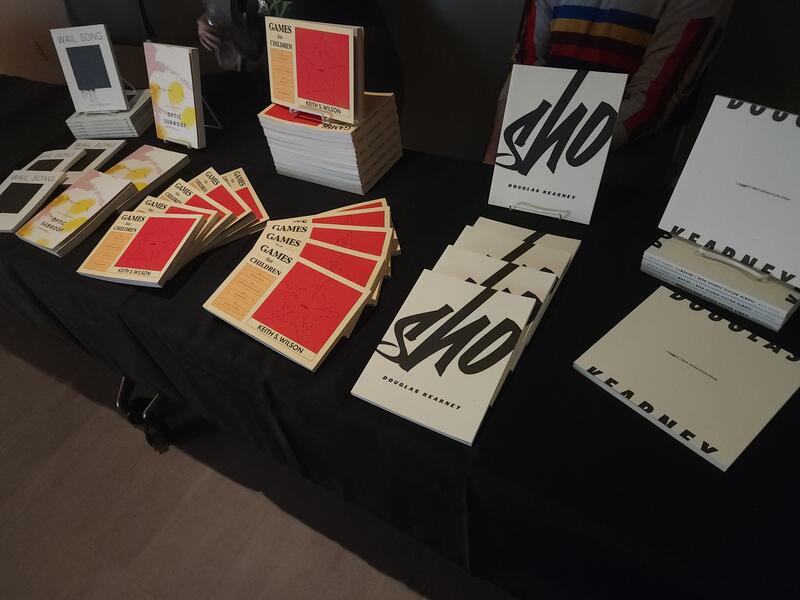

In celebration of our newest National Poetry Series Winner, Milkweed hosted a reading featuring Keith S. Wilson and his debut poetry collection, Games for Children on September 24th. While here, Keith was joined in conversation with graphic designer and Milkweed Fellow Alex Guerra to discuss the creation of his book cover. Later, Keith took the stage alongside poets Chaun Webster and Douglas Kearney to discuss graphic design, poetry, and how they’ve blurred the boundaries between the two disciplines.

Within minutes of his arrival at Milkweed, Keith S. Wilson and Milkweed Fellow Alex Guerra sparked into conversation over their many common tethers, from their shared hometown of Chicago, their pathways in graphic design, and how Games for Children united them in a shared vision of retro aesthetics. After wrangling them past the bookshelves and between our many potted plants, they convened in the conference room where they swapped books and laptops, sharing how Games for Children took shape.

Bri: Keith, what was it like to see the colorful visual aesthetics of Games for Children come to life?

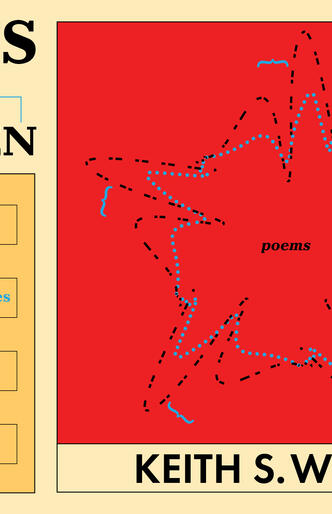

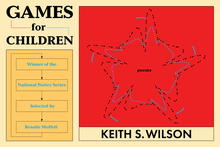

Keith: I love the cover! I was saying a moment ago that it glows. I’m not trained in many practices aside from poetry itself, so when Alex asked about color palettes, I only led with the fact that I used them sparingly. What you did here with the blues, Alex, I would’ve never thought to do that. It’s very different to physically see it in front of me, as someone who doesn’t create printables myself. It was hard to really envision it properly, but I really love this.

Bri: Did you already know what you wanted it to look like?

Keith: No, just the colors, really!

Alex: In the beginning, [Keith] mentioned incorporating retro game design aesthetics, which led to a deep dive in grid ratios and muted, primary colors. Even in gaming manuals, I noticed a grid format, which led to this final cover. There were so many variations you didn’t end up seeing!

Keith: I really want to see them now! All the colors I mentioned ended up on the cover, along with that soft beige in the background that I’d never thought of. I also loved that he used the flower as the cover image. That poem was so big––I never thought it could be used for this kind of thing. There was a point in drafting that I didn’t think it could be used in the book, period. I fully expected to hear ‘yeah, we just can’t use this one.’

Bri: Did you guys work together to come up with the distinct size of the book?

Alex: The shape of the book itself was figured out in production, but we did eventually loop [Keith] in to make sure he was okay with how the poems were formatted before moving forward. That was the bigger lift, figuring out how all these different poems and their variations could even fit into a book.

Keith: There were a couple of poems where the formatting had to be changed, rather than shrinking them down. [Alex] did such an awesome job in this regard––like with my “Gerrymander” poem, another big, square poem. The “Uncanny” poems too, were huge. I think the text had to be shifted there, as well.

When I got the notification I’d won, I had two worries. One, that it was totally unpublishable, that someone would say ‘we just can’t do this’ or ‘we can do this, but we can’t do any of the visual poems.’ Or, that they would do it and the visual poems would be terrible. Thankfully, there was nothing even remotely approaching that here.

Bri: Was there a poem that you, Alex, thought was the hardest to format into the collection?

Alex: Honestly, it might be the visual ‘starburst’ shape that comes from your poem “Uncanny Columbine.” In the initial version, the text had more room. We scaled it down so massively, I was concerned about the stanza placement, since the curly brackets are supposed to point to the text.

Keith: When I got the notification I’d won, I had two worries. One, that it was totally unpublishable, that someone would say ‘we just can’t do this’ or ‘we can do this, but we can’t do any of the visual poems.’ Or, that they would do it and the visual poems would be terrible. Thankfully, there was nothing even remotely approaching that here.

Bri: What made you feel called toward poetry with this collection? So much of it goes beyond the boundaries of poetry––it feels so philosophical and scientific at times, like you’re a cartographer.

Keith: I don’t know that I ever decided that it was! [Laughs] I remember submitting to a nonfiction prize at one point, trying to be open minded. I even printed some poems to physically experiment with them.

Bri: Do you have any plans for future projects?

Keith: I haven’t really started a new project so much as I’ve been experimenting with Games. I was honestly inspired by the animation Alex did for the release. Seeing my starburst shape spinning opened the possibilities that still exist when it comes to animating my poetry. I’m hoping to share the visuals during my readings.

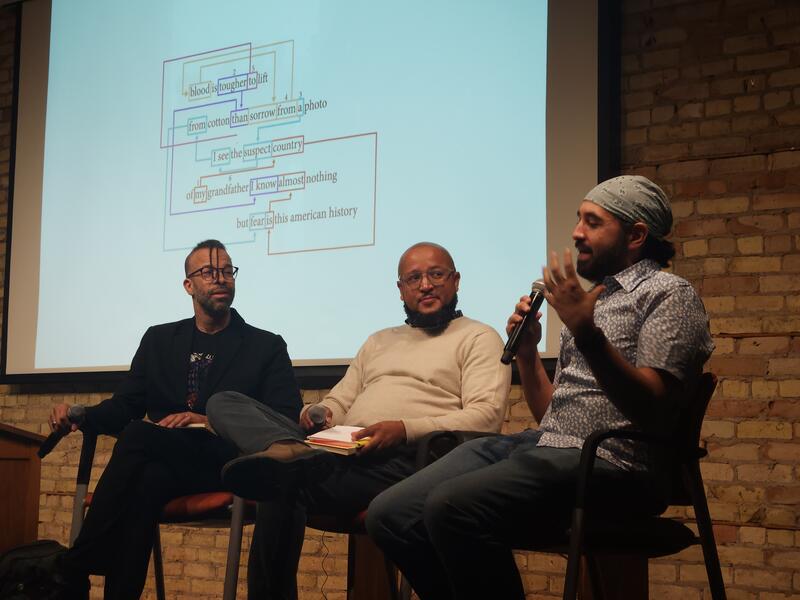

As promised, this experimentation carried into the reading later that night, where he and fellow poets Chaun Webster and Douglas Kearney lit the Milkweed stage in a vibrant, lush flare of animated poetics.

Seeing the starburst spinning on the cover opened up the possibilities that still exist when it comes to experimenting with my poems by animating them.

Keith: I have so many visual poems in this collection that were so gigantic and strangely shaped. The cover was designed by Alex, and I want to thank him and everyone at Milkweed for all their work. I was so moved and touched by [Alex’s] animation that I experimented with Adobe Effects to animate the poem “Line Dance from an American Textbook.”

Chaun: I’ve been so struck by your title, Games for Children. What exactly do ‘games’ and ‘children’ mean for you? Regarding Emmett Till, who features heavily in your poetry, how do you reconfigure him in Games for Children?

Keith: When I think about Emmett Till, especially as it relates to play and being a child, I think of the way that even the word ‘boy’ was utilized to historically diminish black men. It’s ironically used to dehumanize grown men and children. That’s what it represents to me: that there are some people in the world who get to be children, and then there are other sets of people who don’t get recognized for their ability to have innocence. In game design, I know games represent systems and thought-processes in America––particularly as it relates to the ‘winner takes all’ theme. You see it in American game shows and board games all the time.

Douglas Kearney: And yet, they can still function as pedagogical tools, right? Considering the four categories of games: make-believe, chance, competition, and vertigo. You’ve spoken on how they function as rhetoric in your work, and I’m interested in how these dynamics operate in your visual poems?

Keith: I’m so struck by those categories considering that they were once considered higher forms of play, as a dated representation of why certain civilizations were inferior. I’m troubled by what was originally instructional was also inherently insidious. I wanted to observe humanity’s ability to wonder, to look at the sky and marvel at its complexity, to allow ourselves to be awe-struck. Of these categories, I tend to draw toward competition, and how innocence and violence can intersect there.

I wanted to observe humanity’s ability to wonder, to look at the sky and marvel at its complexity, to allow ourselves to be awe-struck.

Accompanying his book release, Keith has also appeared on the Chicago Poetry Center’s interview series All My Friends are Poets. For more on his upcoming events and interviews, please visit his author page.