Dear Rez Kid: Author Q&A with Jake Skeets on Horses

In anticipation of his newest poetry collection Horses, we sat down with author Jake Skeets—the third poet laureate of the Navajo Nation and previous National Poetry Series winner—to discuss the ways in which his two collections converse with one another, his path forward as Navajo Nation Poet Laureate, and what he would say to every rez kid that speaks in stanzas, and dreams in poetry.

In Horses, queerness becomes relational and mirrors the poetics I’m working toward where the land becomes witness, and the body becomes a carrier of meaning. — Jake Skeets

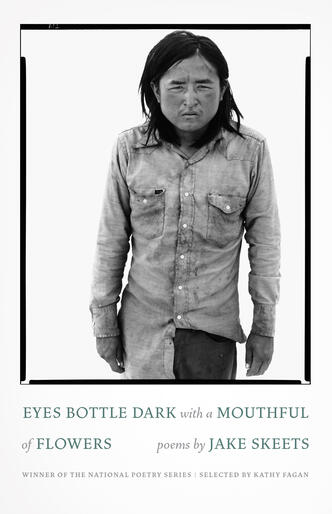

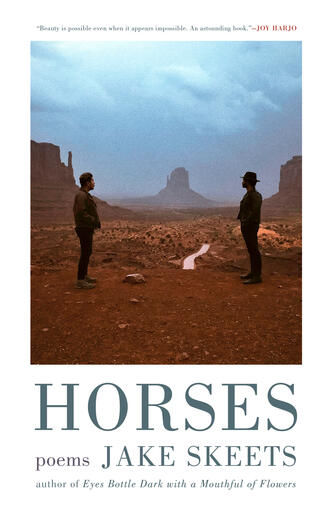

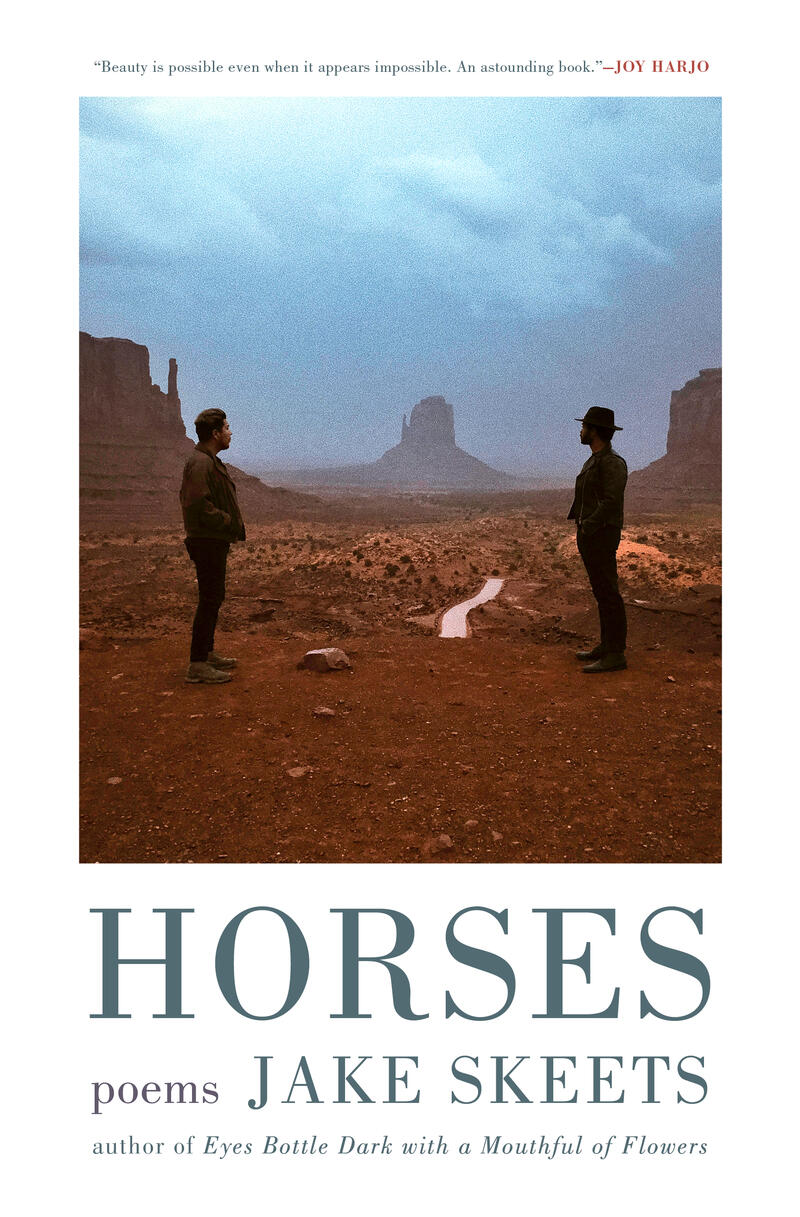

Milkweed Staff: I’m interested in the evolution between your cover photos. Readers have come to understand the tragedy underlying your uncle’s portrait—of which you expand on in your essay for Literary Hub: “it seems as though poetry and photography share an awful lot. Richard Avedon approached the page much like a poet, much like me.” How did that sensibility draw you to Navajo photographer Nate Lemuel’s work?

Jake Skeets: Horses begins where Eyes Bottle Dark leaves off, but its focus widens to hold more of the Navajo Nation. Both books open with tragedy: Avedon’s portrait of my uncle Benson James, a year before his murder in Gallup, NM, and the deaths of nearly two-hundred wild horses in Northern Arizona in 2018. In Eyes Bottle Dark, I was contending with the tension of the Avedon portrait and the complicated fact of a white photographer shaping an image of my family. I found myself interrogating the way he removed land and any sense of orientation, which leaves James as a subject vulnerable to a decontextualized reading. In my own work, I practiced the same kind of economy of white space but as a form of reclamation. I learned from Avedon’s erasure that erasure is a way I can take back narrative control and protect myself against the ways Native experience can be cannibalized by an American market. Lemuel’s portrait on Horses is not about removal, but relation. Two men are standing together, looking out toward Monument Valley. The land is not erased. The land is centered. The dialogue sparked by these two covers I think reveals a shift in my own practice as a writer. The first cover asked me to reckon with reclamation and the second invites an even queerer, relational type of seeing. In Eyes Bottle Dark, queerness became about discovery and finding shape. In Horses, queerness becomes relational and mirrors the poetics I’m working toward where the land becomes witness, and the body becomes a carrier of meaning. In this case, the idea of apocalypse and climate catastrophe was felt through an Indigenous and queer body where futurity has often been conditional. In Horses, I’m really hoping the story can become a way we hope for more.

Milkweed Staff: So many of the poems within Horses play with time travel and memory. If Horses asks us to travel back through time to a point of tragedy, I’m curious—what memories of horses takes you back, in your own memory, to points of beauty?

Jake Skeets: I didn’t actually grow up with horses. My uncle had a horse, and I remember riding it with him walking alongside. I also remember running from wild horses that chased my brothers and me across the cornfields by our house. We once hid inside a juniper tree because we were scared. Those memories are funny now, but I think they taught me that horses on the rez aren’t exactly symbols, but beings with their own intentions, moods, and even sovereignty. The beauty for me comes less from the romantic idea of horses and more from what they represent across Diné songs and stories. Navajo Horse Songs have always reminded us that horses are part of a relational world. They carry prayer, story, and even us across the emotional and physical landscape of the rez. Even though horses weren’t central in my childhood, they were everywhere around me: on the land, in ceremony, in the language my aunts spoke. When I think about beauty, I think about the way a horse can stand perfectly still in the morning light, steam leaving its body in thin threads. I think about how they watch us, how they run, how they exist beyond us. Those memories, both my own and inherited, are what felt important to carry into the book. The beauty of Horses isn’t about nostalgia or animal-as-companion, but about how a relational world is one way we can open space around us where grief, hope, and land can speak with another.

If Eyes Bottle Dark is the ceremony, Horses is the morning after … the drive home. Ceremony is often diagnostic as much as it is a sense of renewal. In Diné, t’áá hó aji t’éégóo is a term we use to articulate how it’s our responsibility to practice the art of being alive. It translates to “it’s up to you.” So, after you drive home from ceremony, you should be in a reflective state, noticing the way the land shifts around you along with animals, plant life, and weather. — Jake Skeets

Milkweed Staff: Connected to this notion of time travel you’ve touched on in previous essays, readers will be taken back to that exact moment of tragedy, of horses pinned, mid-running, mired in mud. Why did this feel like the right point to begin?

Jake Skeets: I often talked about the way Eyes Bottle Dark is a kind of ceremony, weeding through generational trauma while coming into one’s own kind of truth. If Eyes Bottle Dark is the ceremony, Horses is the morning after; it’s the drive home. Ceremony is often diagnostic as much as it is a sense of renewal. In Diné, t’áá hó aji t’éégóo is a term we use to articulate how it’s our responsibility to practice the art of being alive. It translates to “it’s up to you.” So, after you drive home from ceremony, you should be in a reflective state, noticing the way the land shifts around you along with animals, plant life, and weather. You should have an orientation toward the future. Diné poet Rex Lee Jim talks about this, the power of morning as a signal of futurity. My hope is that the horses in the beginning of the book become a metaphor for our current moment. We are pinned right now, mid-run, becoming mired in the mud of our current circumstances. It is up to us to discover the ways we move through these times toward a morning hidden beneath the horizon.

Milkweed Staff: In previous interviews, you’ve spoken about how Eyes Bottle Dark emerged from workshop spaces, while Horses evolves beyond that. Do you see this new collection, then, as a project book? I was struck by the explanation for the stock pond incident at the end—the way it jolts the reader into a haunting and disorienting new context. It made me immediately begin with a second, closer reading. Was that always intentional?

Jake Skeets: Yes to the first question. And not exactly to the second. The pandemic really altered my approach to poetry. I couldn’t write poems, then. I was also moving through the successes and hard lessons of Eyes Bottle Dark, all while the world was seemingly ending around me. Once I started writing poems again, they felt very disconnected to me. Eyes Bottle Dark naturally fell into place with my uncle’s portrait as a kind of anchor. Horses, however, went through several versions and titles. It was also a book I was writing on my own because Eyes Bottle Dark was my MFA thesis. Horses, in this way, is really a debut because I wrote it outside workshop. The world and the archive of poets around me became my workshop. The pandemic, though, offered me time to research because we were all homebound, of course. I was living on the reservation at the time, teaching at Diné College, and our reservation lockdown laws were strict with curfews and literal roadblocks. I began researching for my first novel actually, reading through issues of the Navajo Times. This is how I stumbled across the article about the wild horses. The images that the news outlets shared were devastating to me. In a way like with the Avedon portrait, Horses was born there, in that moment between photograph and poet. The event became then the project of the book: an exploration into desire and hope while the threat of climate catastrophe continues to grow. However, this happened after the book was mostly written. So, Horses was a project of mapping poems I had written and poems I still needed to write. My third poetry manuscript is also centered around a portrait, this time a student portrait of me in kindergarten. I’m hoping to maybe round out these three books as a trilogy in a manner very similar to poets like Sherwin Bitsui. He has said his first three books are also a kind of trilogy. So, at least for the near future, I’m interested in the book as a project and not necessarily a collection of poems.

When writing Horses, I kept hesitating to include my poems about queerness because I thought I needed to write solely about climate change and its impacts on the Navajo Nation. However, I learned that I cannot separate my body from discussion about land because the land is also my body. — Jake Skeets

Milkweed Staff: In Horses, I’m reminded of your essay on Literary Hub: “I cannot separate my queerness from violence just as I cannot separate land from my queerness or tragedy from beauty.” That single quote seemingly encapsulates the distinct yet intertwined lives each book inhabits. How do you see them in conversation with one another—from the poetics of queer masculinity to the vision of a new world emerging from climate change?

Jake Skeets: Queer theorists and scholars have talked about queer futurity as conditional, and this is true within Indigenous communities. How much we align with a colonial agenda is how much more we earn within the colonial machine. So queer Indigenous bodies are a site of intersection where having a future is likely linked to how straight one can become and how colonized, for lack of better words. What does that say then when that same future is also under increasing threat of climate catastrophe because of the very same systems that make the future conditional anyway? It’s a house falling in on itself. It’s an American dream crumbling into fantasy. There is no true country here. It’s all been a business in some way, a machination of empire. When writing Horses, I kept hesitating to include my poems about queerness because I thought I needed to write solely about climate change and its impacts on the Navajo Nation. However, I learned that I cannot separate my body from discussion about land because the land is also my body. I write about this in my essay “The Memory Field.” I turned again to queer poets and found books like Doomstead Days by Brian Teare where he writes:

“I stand on the bank

& know I’m not

supposed to posit

an analogy

between the river

& my body but”

I cut the quote there because I wanted it to land on the word “but” with my book following after. This part of Teare’s poem taught me that we all see ourselves detached from the land, but the very same systems that steal resources from the land also extract things from us. I wanted to align the body with optimism around climate change on the Navajo Nation and elsewhere with the intention of illustrating how hope can be a felt thing. We embody hope when we strive for pleasure and joy. The one goal of patriarchy is to take us away from our own bodies.

Perhaps the only role poets ought to have in community is to love; show love, do love, be love. In Diné, as you know, there is no real word for love because love is an embodied thing, love is something you do. — Jake Skeets

I don’t want to tell poets how to move through the world. I don’t think poets ought to tell anybody how to do anything. We make meaning of the world around us and that ought to be enough. But the study of our surroundings reveals the systematic inequity and violence around us. We witness it, we feel it, we heal from it, we witness it again. Poets and writers then have a unique sensibility to make that cycle something more perhaps. Benjamín Labatut said “fiction gives reality a human shape” and that is a terrible but beautiful responsibility. James Baldwin said “the effort to be a writer is an act of love and an act of faith.” Perhaps the only role poets ought to have in community is to love; show love, do love, be love. In Diné, as you know, there is no real word for love because love is an embodied thing, love is something you do. I love where I come from, I love my family, I love the land that raised me and I am compelled to enact that love in any way I can.

Milkweed Staff: Your Navajo Nation Poet Laureateship comes along the wave of Arthur Sze’s appointment as our U.S Poet Laureate. As two alums and fixtures from the Institute of American Indian Arts, do you see yourself collaborating with Arthur to intersect your dual roles between your laureateships?

Jake Skeets: I’m sure in some distant future, poetry scholars will see the various ways that Sze’s poetics shaped contemporary Native poetics. Sze taught so many Native writers with a lasting impact; Sherwin Bitsui and Layli Long Soldier are two good examples. His attention to language I believe is the way we nurture language. If language is alive, we must tend to its roots, its blossoms, its roots. Sze teaches us that. “No part of language is worth more than any other,” as Sze says. I’m happy to say that I’ve worked with the two Poet Laureates so far: Joy Harjo and Ada Límon. I would be honored to work with Sze in any capacity.

So dear rez kid, your life is waiting for you and it’ll be beautiful. In the meantime, learn as much as you can. Make sure to shake hands with everybody at family gatherings. Help wash the dishes. Write things down. Read everything you can. This moment of your life goes too fast. — Jake Skeets

Milkweed Staff: From the time you first broke into publishing through winning the National Poetry Series to becoming the third Navajo Nation Poet Laureate, I feel so many emotions with my own memories growing up, taking road trips to Vanderwagen for ceremony. I am awe-struck at the growing possibilities emerging for Native kids from our communities, particularly in publishing. I have been that rez kid once, reading to escape. What would you say to a rez kid out there right now, at this moment?

Jake Skeets: There is beauty on the rez that you can only truly see and feel when you leave it. I know it feels like the rest of the world is far superior to the rez but there is no way to compare the two. Each have their value. Each have their dangers. So dear rez kid, your life is waiting for you and it’ll be beautiful. In the meantime, learn as much as you can. Make sure to shake hands with everybody at family gatherings. Help wash the dishes. Write things down. Read everything you can. This moment of your life goes too fast. I wish I could remember more. I wish I did more. Don’t be dumb, be curious.

Milkweed Staff: You’d mentioned that the book’s title was loosely inspired by Patti Smith’s album of the same name—I’m curious to hear more about this connection!

Jake Skeets: Horses came after most of the book was written. So I turned to Luci Tapahonso, Laura Tohe, Joy Harjo, and Patti Smith during the revision process. Particularly, the song “Land” from Smith’s album is a song I listened to on loop. I was researching a way to use the long form in poetry. I read a lot of book-length poems like Sherwin Bitsui and Brian Teare. I also read poets like Arthur Sze and Garrett Hongo. Eyes Bottle Dark was very fragmentary. A Goodreads review called the book a poetry collection cut in half. I employed the sentence, then. The twelve-part title poem “Horses” opens the collection. I wanted to carry a poem across pages so from there we spiral and meander across the Navajo Nation, through space and time, through language until we arrive at the promise of the next world.