Debra Magpie Earling on surfacing through silence: “The time is now.”

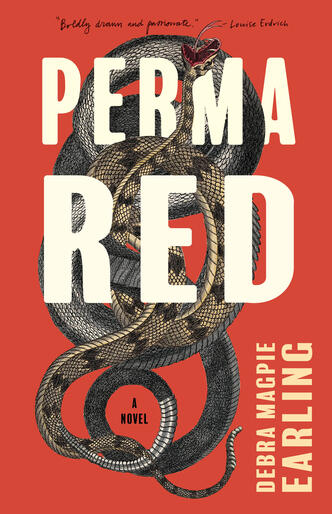

Debra Magpie Earling wasn’t exactly surprised when her first novel, Perma Red, was banned after its re-release in 2022. She’d already faced more than her fair share of adversity bringing the book to fruition: after spending nearly a decade conceiving of the first draft, she would lose it to a cabin fire. After tirelessly working to rewrite the story, she’d be advised—repeatedly—to adapt the ending of the work to cater to Western audiences. And after finally signing her first publication deal in 2002, the imprint would shutter its doors and force the novel out of print just four years later. But Earling was determined to stick by her story, which sheds urgent light on the ever-present erasure of missing and murdered Indigenous women’s narratives. For Earling’s story to break through the surface of silence not once, but twice, was nothing short of a miracle—but as Earling herself confirmed in her latest conversation with Milkweed Editions, it was also only a matter of time.

“I think times are changing now,” Earling said, referencing Indigenous author Tommy Orange’s There There as hopeful proof.

When I first set out to publish my book, I was told I couldn’t kill the heroine of my story…then my editors pressed me for details—they wanted more of an explanation for the ending. But the point was the mystery: no one knows what happens to missing and murdered Indigenous women. There’s a network of silence and silencing on the rez.” She then continued, “America is so burdened with the guilt of what is happening in tribal communities across the US, and in particular Montana. And despite whatever protective bills have passed there’s still an assiduous oppression of womens’ stories. How is the Western need for a [decisive] hopeful ending indicative of this?

Where another writer may have balked at the obstacles in the path to (re)publication, Earling’s inquiry above hints at what she knew was at stake: Who knew how long it would take for the next Indigenous author to be given a platform to speak out against American colonization and its countless harms? Earling had experienced them first- and secondhand, after all—despite being reimagined within a fictional lens, her first novel represents the real-life narrative of Earling’s aunt Louise, the eponymous “Perma Red.”

In an age where silence has become widely regarded as complicity, the Indigenous author was determined to not only address the long-held silence of missing and murdered Native women through her work, but also to break through the silencing of BIPOC authors which has picked up legislative steam along with a series of strict book-banning measures throughout the US. For those of you who have already read Perma Red, it would seem clear that her own courage in speaking out against oppression and historical whitewashing was undoubtedly inspired by the legacy of her aunt. With a misty softness in her voice, Earling reflected on Louise’s character: “She was such a strong woman, and she wanted to assert her independence and agency in a time when it wasn’t possible. When she was in boarding school, she stood up for people and didn’t kowtow to anyone. She had a certain allure, and an indelible spirit.”

In a past interview with Milkweed staff, the novelist opened up about the moment she first learned Perma Red had been banned in school districts across the state of Montana. Earling rightly identified how the actions of a single individual spoke louder than state-sanctioned silence: “Without [that one] teacher’s study, [Perma Red] would have remained in the dark, snuffed from public light, unseen in that community. She brought it out and had students read it whether they wanted to or not. It was a small brave act that became large. Readers cannot respond to a story kept in darkness.”

Today, Milkweed Editions is proud to celebrate beloved author Debra Magpie Earling not only for the traction and visibility Perma Red has gained both in spite of—and in some ways, because of— its banned status, but also because of her inspiring ongoing commitment to telling her story in new and accessible way. By seeking a path forward for the retelling of Perma Red on the big screen, Earling hopes to transcend the confines of the literary world and return her crucial message to the very underserved communities it is rooted in. “What I wanted more than anything was to have this story come to light, to become more than simply an oral history that gets passed around [and trapped in] the reservation,” Earling said.

I wanted to open up the story. I wanted it to reach people it otherwise wouldn’t. If it could be made into a series or motion picture, it would reach a wider audience, and maybe for just ten minutes it would stop someone from saying something derogatory about rez-life today or Indigenous people…The time is now for [these] stories to rise up…for us to change this narrative and open up the door to let Native people tell their own stories in powerful ways. And I think this story does exactly that, and also has the power to call for a different kind of silence—it’s the silence after a story that leaves room for justice.