Deep Cuts—Larry Watson's Let Him Go

Hello, friends, and welcome to another edition of Deep Cuts. In this series, we dive in with some of our authors and discuss the behind-the-scenes work that goes into the composition and production of their books.

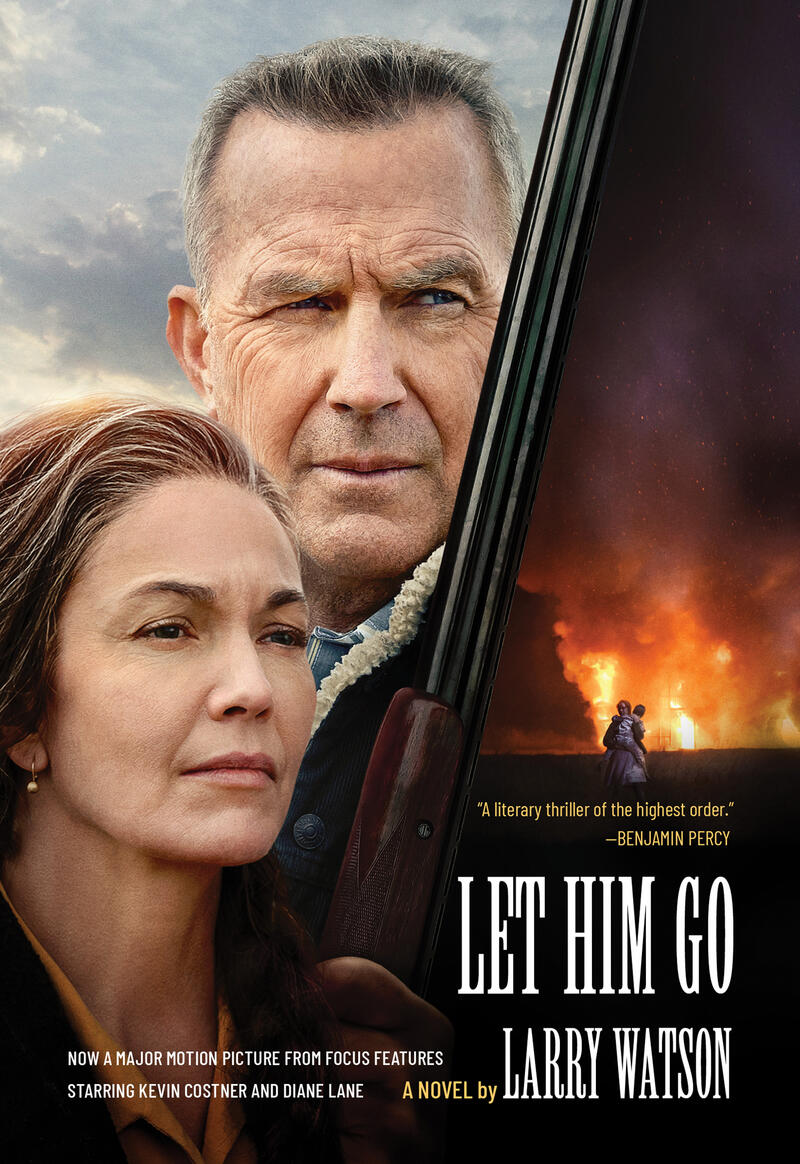

We’re all about transformative literature here at Milkweed—y’all know that—but this month we got to see a slightly different kind of transformation: Larry Watson’s Let Him Go, a novel we originally published in 2007, transformed into a Focus Features film. What sorts of changes happen between page and screen? How might an author feel seeing a character they wrote find life (literally) in an actor? What is the logic behind cutting a scene when adapting a book into a screenplay? (The answer might surprise you!)

Read on to learn more from the ever-insightful Larry Watson himself. And check out the excellent new cover of Let Him Go while you’re at it!

Bailey Hutchinson: What originally led you to this story? To these families, the badlands?

Larry Watson: With this novel, as with others I’ve written, a few things had to come together before I knew I had a story, or at least enough story to begin writing. It’s like cooking from a recipe—you take this ingredient, that ingredient, a little of this, a pinch of that—but you can’t make the thing until you learn how you can mix all the ingredients together.

Here, for example, are a few ingredients for Let Him Go: Our daughter, her husband, and their son were moving from their home in a small Wisconsin town. They stopped at our house on their way to their new home. I remember saying good-bye to them, and thinking, What if … (so much of writing fiction for me is answering what ifs), what if they weren’t moving sixty miles away but six hundred, six thousand. We wouldn’t see our grandson very often if at all. I had that feeling to draw on in writing the novel. My wife and I had seen more than a few examples of grandparents who competed with other grandparents to be the favorites. Sometimes those competitions were tied up with which family name or legacy was superior. (My parents had many quiet disagreements over whether it was better to be a Watson or a Peterson.) I remembered growing up and hearing about certain families that were trouble and to be feared and avoided. (The truth was probably that they were troubled.) I’ve often used borders in my fiction, of both the literal and metaphorical kind, to put characters in unfamiliar territory (both literal and metaphorical). Many of us grow up with warnings that it’s dangerous to leave here and go there, and the border separating here and there is often quite distinct. (It doesn’t matter that the people on the other side hear the same thing.) “Badlands” make a good symbolic division between those good and bad regions, and the Dakota Badlands are a literal area that must be crossed when traveling between North Dakota and Montana.

All of those elements sound pretty highfalutin’, but I could just easily have mentioned an image that occurs in the novel’s opening pages: the smell that permeates a household when the furnace comes on for the first time in the fall. I had that image in my mind for a long time, just waiting for a chance to use it. This novel gave me the opportunity, and it was an ingredient as important as some of the others I’ve mentioned.

BH: Can you tell us a bit about adapting Let Him Go for film? How involved were you in the process? What surprised you?

LW: I was not involved in adapting the novel for film at all. Thomas Bezucha and I had conversations about the novel, both before he had secured the rights and after. We continued to talk occasionally, and he kept me abreast on how the project was moving forward. I knew early on that we shared an understanding of the characters, and we saw the story’s basic themes, as borne out by the action, in similar ways. He told me about how the screenplay would differ from the novel and why, and since our talk always included the different demands of each medium, I understood his changes. But I didn’t, and still don’t, feel at all proprietorial about the story. I wrote a novel, and Tom Bezucha made a movie. First I did my thing and then he did his.

But here was something that I can’t say surprised me but that did illustrate nicely the difference between making movies and writing novels. Tom said he eliminated a scene in a gas station because he didn’t want to build another set. If, in writing fiction, I want a scene in a gas station, I simply write, “They pulled into the Texaco station.”

BH: I’m so interested in what we know about our stories before we write them and what our stories tell us as we write them. Did seeing your characters take on new life in film lead to even more discoveries?

LW: No, mostly because when I saw the movie I no longer thought of the characters as “mine.” They were characters in a movie that I watched as any moviegoer would—entertained, moved, and, sometimes, edified by what those characters said and did.

Once a novel of mine is published, the mental files I kept while I was writing it erase themselves very quickly. When I watched Let Him Go, I couldn’t tell whether a line of dialogue, for example, came from the book, and I wasn’t interested in making that determination.

But I certainly know what you’re talking about when you say, “what [our stories] tell us as we write them.” That could be my personal writing motto. I believe our stories are always trying to tell us something. If we ignore those instructions, suggestions, murmurings, we do so at great risk, for it’s on those occasions that we have opportunities to make discoveries about our material and perhaps even about ourselves.

BH: I’m thinking about your descriptions of autumnal northeast Montana, of Margaret’s recollection of a summer so hot the earth “cracked like a dinner plate”—all of your landscapes, really. I wondered if you might speak to the differences between your vision of places on the page versus how they manifest on screen.

LW: My response here is similar to my response to the previous question. When I watched the movie, I noted where actions took place, and the rightness of those locations and images for the movie. Those settings, both interior and exterior, had their own reasons for being and for the director’s vision and understanding of the story and its themes. And of course he had to find actual locations to be filmed to represent his vision. All I had to do was imagine and/or remember places and scenes and then find language that would convey the images. I think my job is easier. But the mediums are different. Comparisons of books and movies have always confounded me. We should all probably stop making them.

BH: I often ask authors what they’d include on a reading list for their books, but I think I’ll take a different approach this time around: what films would you include in a movie marathon culminating with Let Him Go?

LW: What a great question—and there are so many ways to answer. So I’ll do exactly that—go in many different directions.

Let Him Go is, among other things, a road trip movie and a doomed one, so how about Thelma and Louise?

It has noir-ish elements so Blood Simple, the Coen brothers’ first film. Especially for one particular scene and its special brand of violence.

The Searchers. Because both the Blackledges and Ethan Edwards embark on quests to find a family member and bring that person home.

Because a ruthless, manipulative woman rules the brutal Weboy family, how about Animal Kingdom, a 2010 Australian film about the scary Pettingill family?

The movie has two strong women in a western setting, so perhaps Barbara Stanwyck in Forty Guns or Joan Crawford in Johnny Guitar, both movies from the 1950s.

How’s that for a film festival? We could call it “Movies That Seem to Have Nothing in Common.” And probably don’t.