Deep Cuts: Northern Light

Hello, friends, and welcome to another edition of Deep Cuts! In this series, we dive in with some of our authors and discuss the behind-the-scenes work that goes into the composition and production of their books. This month, I’m so pleased to be featuring Kazim Ali’s Northern Light, a ruminative study of the word home.

Northern Light opens with a photo of a young, smiling Ali. He’s standing at the end of one of three rows of children—Jenpeg School’s ‘77-‘78 class of first graders. I’ve found myself lingering on this page, studying the various expressions marking the children’s faces, noting the nearby teacher’s sharp, polka-dotted collar; one child’s decidely seventies eyewear; Ali’s own smile, small, somewhat fogged by time and grayscale. It’s a pointed preamble for the coming pages—as is, for that matter, the overhead photo of Jenpeg, a community that no longer exists, that follows shortly thereafter. How does our relationship with a place change when it has been transformed by time, by distance, by colonization and industry? Even the cover of Northern Light (seen below) seems to ask this question—and in the midst of this hefty inquiry is Kazim Ali, weidling a poet’s patience.

In this round of Deep Cuts, we’ll see a bit more of the region and peoples so thoughtfully witnessed in Northern Light. Read on to hear from Ali himself about land, lineage, and his time with the Pimicikamak community.

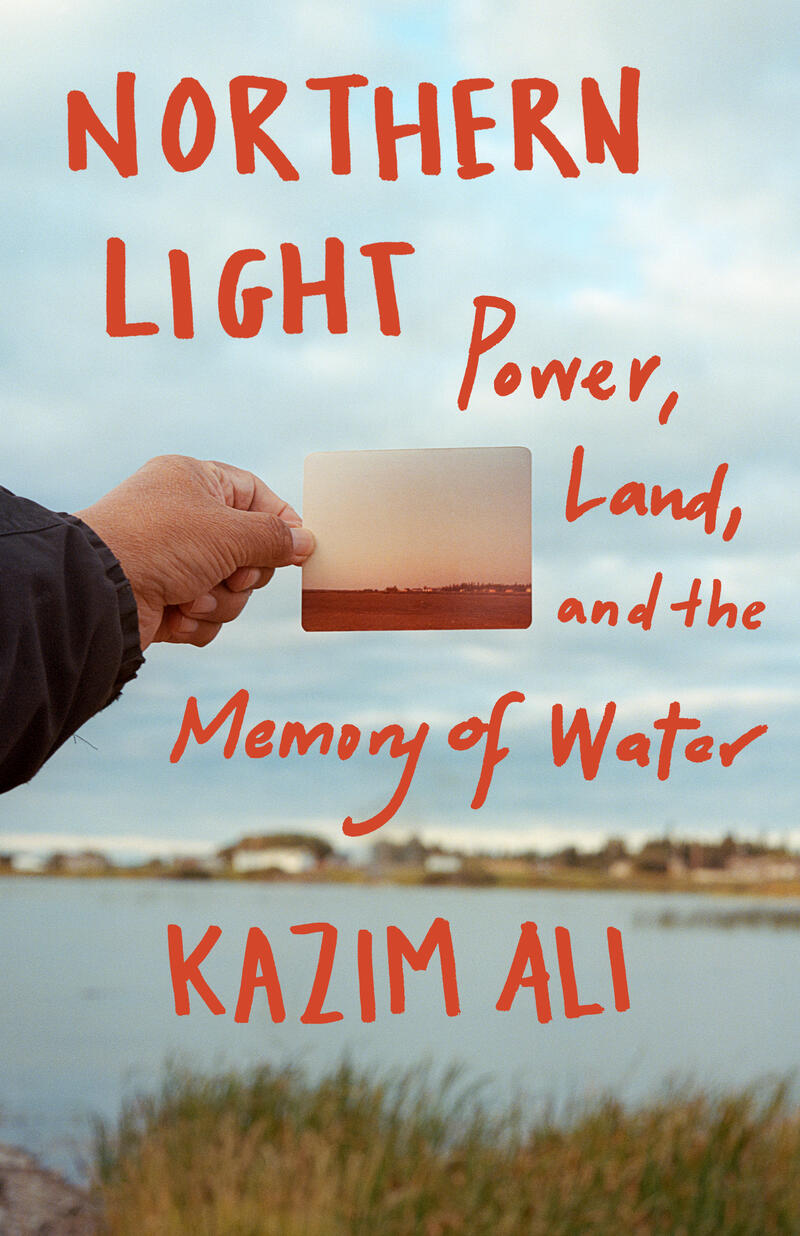

Jenpeg

Kazim Ali: This aerial photo of the little company town Jenpeg was taken by one of the men in a helicopter. All the houses you see are single and double-wide trailers. There were five main residential streets in the town of which you can see three in the upper part, and single residential street for management on the lower end of the photograph. My family lived in the trailer fifth from the right on that lower street. The larger buildings (in the upper right of the town) include the community center, a dormitory for the single men, a restaurant, a tavern, a curling rink, and the general store. Off the picture to left was where the school (serving K-8) and outdoor hockey rink were.

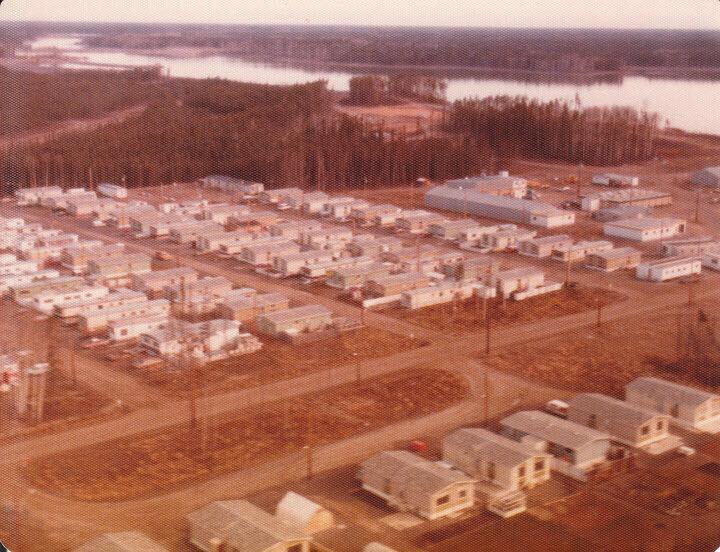

Cross Lake

KA: This picture was taken on my second trip to Cross Lake (the book recounts my original trip). Water and land are intertwined there, and there’s almost more water than land. Western concepts of “territorial water” or land and water as separable entities with rules around resource extraction of various taxonomies do not exist in the Pimicikamak world view, which sees the landscape and water (inclusive of animal, plant and mineral) as a unified system whose various components function in interdependence.

Chief Cathy Merrick

KA: Chief Cathy Merrick invited me to Pimicikamak to see first hand the environmental impact of the dam and the various ways those changes had affected the social and cultural life of the community. In the book I recount the time we sat down to talk about her journey in politics, her election as only the second woman chief in the nation’s history, as well what she sees as the most pressing issues facing the community.

KA: [Chief Merrick] is much loved in the community, but the internal politics of the community are robust and competitive and so we talk also of the many challenges she faced.

Two Gravestones

KA: One key motivation of writing this book (indeed the question with which it opens) was to interrogation to concept of being “from.” What does it mean, who earns the right, what privileges does it afford one, and what are the ways in which one is excluded if one is not “from”? I haven’t lived in Canada for forty years, neither was I born there, but I still have citizenship by virtue of the kind of documents my family had when we went there. And there I learned language. And there lie the bodies of grandfather and my uncle. Are those two last facts enough to make me “from” that place?