Excerpt: Kazim Ali's Northern Light

The simplest of questions is most complicated for me: “Where are you from?” I have no answer. But I most often think of a place I wasn’t born in, only lived for a few short years, and after moving away, didn’t visit for decades. When I was three or four my family moved north to the boreal forests of Canada, where my father worked for Manitoba Hydro helping to build a dam across the Nelson River to provide electricity to the province. Nearly forty years would pass before I learned of the impact of that dam on the ecosystem, the social, economic, and spiritual fabric of the Indigenous community upon whose land it was built, and the challenges in physical and mental health that community was facing. This book tells the story of my return, but more importantly it tells the story of the survivance of a community, fighting to overcome generations of colonialism and exploitation. I wasn’t sure what I would find there. Was I going as a poet, a journalist, a memoirist, an ethnographer? I didn’t know. But I knew I had to go.

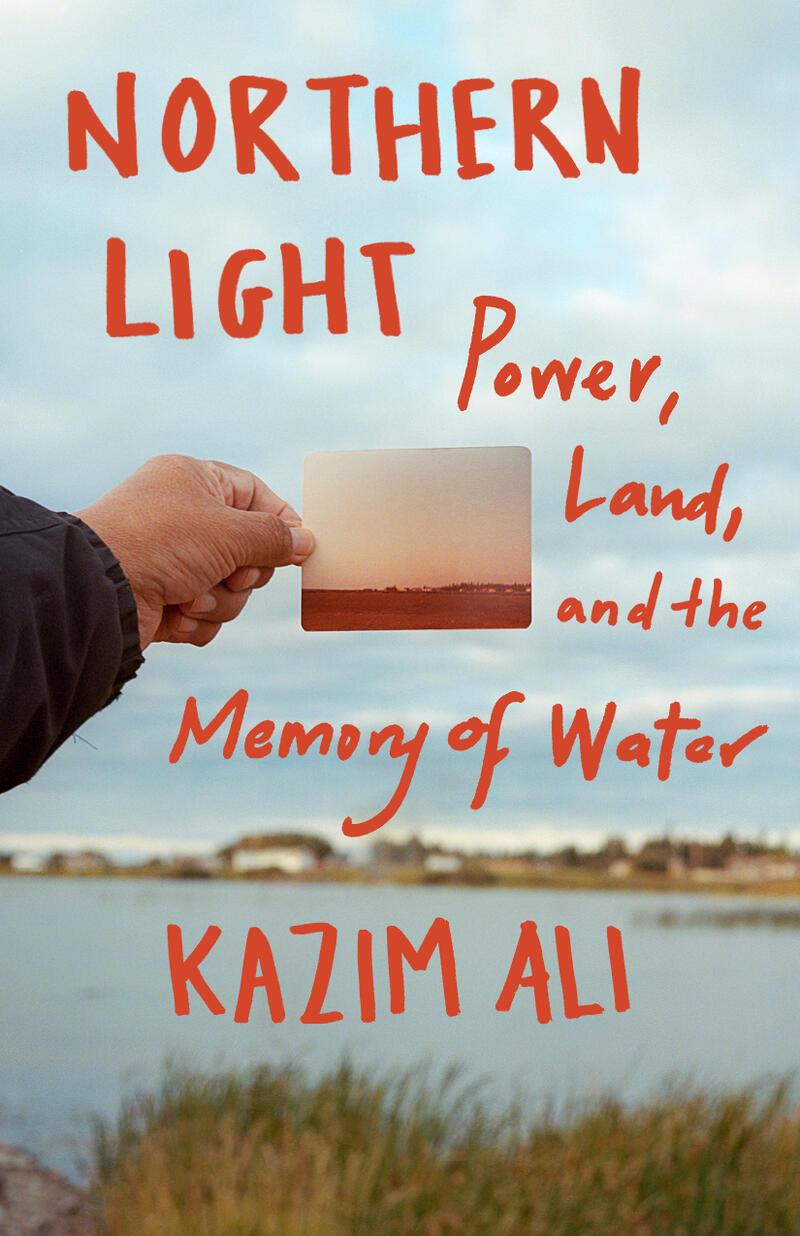

What follows is an excerpt from my book, Northern Light: Power, Land, and the Memory of Water, forthcoming March 2021. One of the Indigenous community members featured in this excerpt, Jackson, is the photographer of the photo you see on the book’s cover.

—Kazim Ali, author of Northern Light: Power, Land, and the Memory of Water

EXCERPT

On our drive, I am captivated anew by the quality of the northern light. It always looks like it’s been raining: the yellow-white golden color of the dry grasses; the muted green of fir trees and the wet black of their trunks, with pale, dirty-white paper birches interspersed; blue smoke of the clouds, and then luminous and dark gray, the soft heavy sky billows pulsing with incipient light above. The lake–broken branches rising here and there above the water–seems resentful, treacherous, resigned.

At Jackson’s direction, Donald pulls over and we clamber out of the car. “Okay, now close your eyes,” Jackson instructs, then guides me across the road to its shoulder, facing the lake. “Now open your eyes.”

Jackson is holding up a photograph in front of my face. I can see the actual lake to the left and right, and he is holding the picture so I can see the continuous shoreline and a small sandy beach with a promontory of three large boulders. “This picture is from ten years ago,” he says.

“Now look.” And his arm drops away so I can see the shore now.

“The whole beach is gone!” I exclaim. “Those protruding rocks too.”

“They’re all underwater,” Jackson says, pointing in the direction where the rocks lie submerged.

During construction of the Jenpeg Generating Station, Manitoba premier Ed Schreyer promised that water levels would not change beyond the negotiated limits, and this provision was written into the Northern Flood Agreement. During a 1975 press conference announcing the plan, he famously held up a pencil to reporters and vowed that the water level would only fluctuate the length of that pencil. Forty years later, in response to the 2014 occupation of the Jenpeg Generating Station and the Pimicikamak council serving eviction papers to the province and Manitoba Hydro, Premier Greg Selinger issued a formal apology for the economic and social damage from hydroelectric development, acknowledging that the province had vastly underestimated the impact of the dam. Jackson Osborne commented at the time, “The premier should apologize to the muskrats, to the beavers, to the fish, to the moose.”