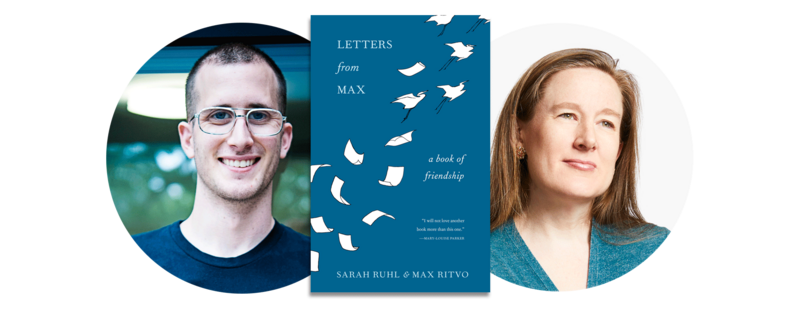

Excerpt: Letters from Max: A Book of Friendship

INTRODUCTION

Max Ritvo began as my student. I met Max when he was a senior at Yale. This is how he began his application to get into my playwriting workshop:

Dear Professor Ruhl,

Thanks for reading this application. My name is Max Ritvo—I’m a senior English major in the Creative Writing Concentration. All I want to do is write.

His application said that he was a poet and a comedian, part of an experimental comedy troupe. A poet and he’s funny? Huh. I reread his application, which had been left to stew in the “no” pile because he’d never written a play before.

And because funny poets are a rare and wonderful species of human being, I moved Max to the “yes” pile, despite his lack of experience writing plays. It is hard to imagine now that Max’s application could ever have remained in any other pile—a strange parallel universe in which I never met Max.

*

Max walked into my first class and it was as though an ancient light bulb hovered over his head, illuminating the room. Skinny to the point of worry, eyes luminous blue and large, even larger under his thick glasses. His eyes (both magnified and magnifying) were especially animated after he’d amused someone, anyone; with a hangdog look, he’d gaze up from behind his spectacles to see if the joke had found a target. His voice: surprisingly booming for so slight a frame. Some rarefied combination of a young Mike Nichols and an old John Keats, he seemed eighty years old and not from this century. Who is this boy? I wondered. He seemed to have read everything, from Vedic texts to contemporary poetry, and yet he had the air of a playful child.

The first missive I received from Max in my inbox began like this:

Dear Professor Ruhl,

I am writing because, before shopping period had even begun or I had even realized that this wonderful class existed, I booked tickets for Einstein on the Beach at the Brooklyn Academy of Music for this coming Friday.

Little did he know that I had longed to see Einstein on the Beach, had tried in fact to get a ticket, but it was sold out. Nothing could have been more delightful to me than a student who had the foresight to book tickets to a difficult and avant-garde theatrical epic. Max went on to apologize and ask permission to miss a class. I told Max that he must go, and I asked him for a short report (no more than five minutes) on the experience of seeing the show. I said maybe he could join us for the first part of class, then hightail it to Brooklyn to hear the great Philip Glass score.

Max wrote back, “Dear Sarah” (it took us two letters to drop the institutional formalities):

The show starts at seven. I’m worried if I leave later I won’t have time to properly get from Grand Central to eat something! The show is four hours long and I have to eat in a really regimented way to keep my weight up as a result of the cancer/chemotherapy I had in high school—more on that some other time.

I now had part of my answer as to why Max was different from the other students, why life and death seemed to hover near him, why (beyond being a poet) he’d already contemplated the big metaphysical questions, why he was so skinny. Max went on:

I would really love to take you up on your offer of some post-graduating advice. What days are you in New Haven, and when would it be convenient for you to be a sage for a half hour?

*

The following week, Max, as promised, delivered an insightful and detailed sermon to the class on Philip Glass and Robert Wilson. He was to have spoken for five minutes—he spoke for about an hour without stopping. (I later learned that a bright young woman in the class was horrified that a man was taking up an hour of her time with a lecture on Philip Glass; she was to become one of his best friends.) In class, Max had boundless enthusiasm. He had highly refined irony without ever being cynical. And if he was aware that his brain made connections ten times faster than most of his peers, he didn’t show it; he just seemed happy to be in such good company.

I met with Max after class at the local bookstore-café, Atticus, where we sat at the counter and ate black bean soup. Max ate slowly, with difficulty, and explained that in high school he’d had Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare pediatric cancer, and the chemotherapy made his digestion iffy. He explained that he was in remission and slowly finished three spoonfuls of the soup. Then he put his spoon down, and spoke about his dreams of becoming a poet, resting here and there to speak about the trials of love. (A girl was probably plaguing him at the time. A girl was often plaguing him.)

The semester wore on, with more deliciously coined phrases from Max in class (phrases like “theatrical onanism” and “lyric complicity”) and more of the same leaves falling on the same gothic campus. Then, in October, another email from Max, addressed to me and to the teaching assistant, Amelia:

Dearest Sarah and Amelia,

I write with sad news. Today was my cancer scanning day and an artifact was discovered in my right chest. We are waiting for more testing and surgical biopsy, but it is possible that this is a recurrence of my cancer. I have every intention of carrying on with my work—I just wanted to forewarn you that there might be some difficulties on the horizon. I can’t say how much you’ve both come to mean to me in my short time learning from you. If nothing else, maybe we’ll squeeze a great play out of whatever comes of this.

Gratefully,

Max

The small class and I were heartbroken.

A hurricane was about to arrive in New York City, and Max was about to go into surgery. The conversations Max and I had about art and life took on a new urgency, and our correspondence began in earnest.

from PART ONE:

NEW HAVEN, 2012-13

OCTOBER 25, 2012

Dear Sarah,

I go into surgery in five or six hours. I will miss you—wish me luck as they cut me and fill me with opium and hand down the unappealable verdict!

I will get everything in, perhaps just not in a timely fashion. The idea of my one act is daunting—I might want to do a cancer one act. And I might want to very much not do a cancer one act. I will only have clarity a little later.

In the meantime, I thought you might enjoy a few poems I’m working on: proof of a fecundity, if unsoundness, of mind. Any comments would be deeply appreciated. I’m clinging more and more to my writing as my panic is increasing—and have just not had the concerted span of time necessary to write some of the staged things that are brewing in me.

X

SCAN

Lie flat,

comes the command,

from a voice unsinging;

the voice starts to weep

and I blow it kisses.

—

OCTOBER 27

Dear Max,

I have been thinking of you and sending you, or trying to send you, powerful wishes of healing.

I loved your poems. You have such an ear, such a mind, such a beautiful singing ear and intellect. Thank you for the gift of them.

I am terribly terribly sorry about what seems to be the news of the artifacts. I am assuming that the fact that you emailed yesterday means that you are out of surgery. That is a comfort, and I hope you are resting and recuperating from the invasion.

I want you to write in any way that makes sense to you this semester.

Max, is there anything I can do to help? Happy to visit the hospital if you’re up for visitors, or do you need books or distractions? Or if there’s anything I can do for your mom while she is in New York during the hurricane?

We are all rooting for you,

Sarah

—

OCTOBER 29

Sarah,

I can’t tell you how much your note means to me.

I am in my room at home—tomorrow, assuming the hurricane doesn’t box me in, I will be back in Sloan’s to receive the protocol. I will be penned up there for two or three weeks. Then hopefully the treatment can be transferred to New Haven.

It would be great if you’re in New York anyway if you visited at the hospital. That would mean a lot to me. Bring me a book and inscribe it! Reading is good. Writing is about all I have.

Today was mostly breathing exercises and limping and coming off of the opiates, as well as the transfer to home. Strange dreams with lots of focus on skin texture. My uncle has flown in from Israel—he gave me some acupuncture, which unblocked a very preverbal chunk of fear and rage—I felt like I was a prophet channeling my tumor.

Max

—

That fall I was knee deep in rehearsal for a play of mine called Dear Elizabeth, an adaptation I wrote of the letters between Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop, that premiered at Yale Repertory Theater. It is strange now to reflect that just as I met Max, I was thinking keenly about the friendship between two writers, expressed through their letters. Bishop and Lowell found in each other’s minds a cure for a solitude particular to writers. When I read their letters for the first time, I found their friendship moving, and desperately wanted to hear their letters out loud. It had not been an easy play to write—I was trying to write while one child was vomiting, one child was screaming, and one child was imploring me to read Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle out loud. At the time, my twins—Hope and William—were two years old and my big girl—Anna—was five.

And that was the state of affairs when I met Max; motherhood and writing had me feeling underwater much of the time. Meanwhile, Hurricane Sandy hit, rehearsals for my play were canceled for a week, no trains were running between New York and New Haven—we were all waterlogged. I found myself stuck in New York at the same time Max was stuck at the hospital.

—

OCTOBER 30

Dear Max,

It certainly feels odd in New York. Thank God you’re uptown and were not at NYU. You must feel a little like Job stuck in the hospital during a hurricane. Like come on, what gives? And a hurricane too?

I want to come see you and probably can’t get to see you until the subways are more under control. Maybe this weekend if you are still in hospital then?

In the meantime, I’m supposed to be in rehearsals in New Haven for my play Dear Elizabeth and instead am madly baking at home (luckily we have power) and creating apartment-wide scavenger hunts to entertain the children.

I will try to think of some books that might entertain you.

Sending all good thoughts,

Sarah

—

NOVEMBER 4

Sarah!

I miss you, and the class. Seeing you this weekend would be wonderful. My mornings are spent in the hospital getting chemo drip and then I’m released to my apartment in the afternoons. It would probably be nice to spare you the childhood chemo ward (which is horrific) and the least functional part of my day, and see you in the afternoon.

I’m midway through the first run of chemo. The side effects seem to be accumulating, but I can talk and walk a little bit, and think clearly if with a marked slowing of pace. I’ll send you some of my writing.

I am so lucky to feel your warmth and concern. You are such a specific helpfulness in my life. Don’t know what I’d do without you.

Max

—

I visited Max after that surgery in New York, at his apartment on the Upper East Side, as soon as Hurricane Sandy allowed me to brave the subway. I brought noodle kugel and met his family. Max teased that though I was a Midwestern goy, my kugel passed his beautiful mother’s Israeli muster. Max was always good company, even post-surgery. I could tell he was furious if he wasn’t well enough to make the people around him laugh. If he was not well enough to make people laugh, he usually told friends not to come by.

I gave him Dear Elizabeth to read because he was wrestling with the ethics of quoting someone else’s letter in the play he was working on. I thought Max would enjoy reading Lowell and Bishop’s whopping fight about the ethics of Lowell using letters from his ex-wife in his book Dolphin.

Max was still very much my student—I gave him notes like “Put that speech in iambic pentameter.” “Bring in that scene rewritten with a 25 percent word reduction.” “Write a little song for that moment.” I would write him about a scene: “I love how specific and never arbitrary you are.” And he would write me about his hopes for a new scene: “I am adamant that something extravagant and silent happen.”

Max handed in his play at the end of the semester. It begins at an altar, and also features a scene in which a sick boy goes to get a new tattoo, but at the tattoo parlor, the tattoo artist is something of an analyst, and the boy and the tattoo artist speak in iambic pentameter. The boy says to the tattoo artist:

“So I have brought inside my little pouch,

a little draft of a Hokusai crane.”

Max got a tattoo after every surgery. He wanted to make something beautiful out of something painful. They were all birds, modeled after different artists. One was a crane, inscribed on his head, inspired by the Japanese artist Hokusai. In his tattoo parlor play, Max wrote these stage directions:

The tattoo artist finishes, and picks the boy up, very gently like an angel helping another angel. She offers him a compact mirror gently like an angel offering a compact mirror to another angel. He smiles and begins to check it out.

Then the boy says: “It’s dope. I really love it in this light.”

From Letters from Max: A Book of Friendship by Sarah Ruhl and Max Ritvo.