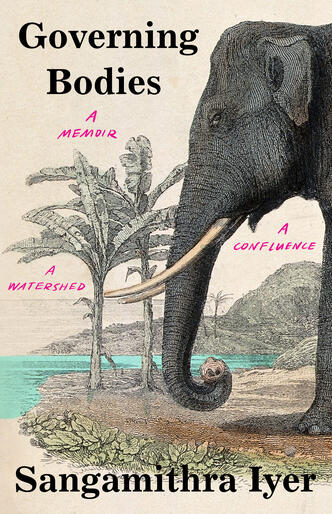

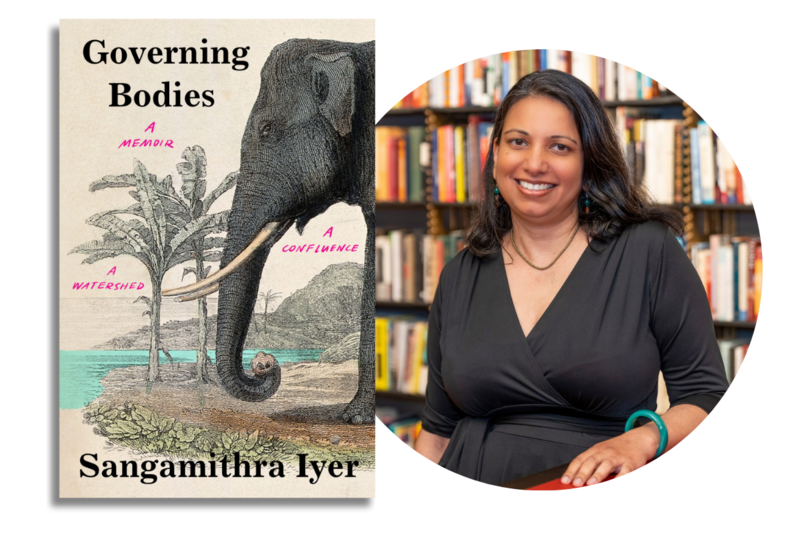

Governing Bodies: Author Q&A with Sangamithra Iyer

In anticipation of the release of Governing Bodies: A Memoir, A Confluence, A Watershed this fall, we sat down with author Sangamithra Iyer to learn more about the structure, themes, and interconnected layers in the book, including her work with animal rights.

Milkweed: Governing Bodies is uniquely structured. Can you talk about how you came to that form and why you chose it?

Sangamithra Iyer: Governing Bodies was an ungovernable book to write. The structure was not something I could engineer or impose. The blueprint didn’t come first; it was shaped with iteration over time.

I had been accumulating stories, learning to care for them and make meaning and connections. I was continually beginning again. The process was cyclical—like water repeatedly coursing through a river. Every time I returned to the work, I had changed, the river had changed, and the book had changed. I wanted to be able to capture this on the page. Water was not only a subject or a setting in my work, but also became my teacher. Water can take the shape of any container. A river can be narrow and fast or wide and slow. I needed a shape for this story, expansive and flexible enough to convey all I was carrying.

A few years ago, I sketched out the flow of the book’s contents. I was thinking about the book in three sections: one focused on my paternal grandfather, who I never met, and the parallels in our lives as engineers and activists; another oriented to my father, who passed away in 2003 and whose death prompted many of the questions that animate this book; and a third, my record of living through this time of compounding planetary crises and creating the archive I wanted to leave for the future. I had this big epiphany then—my book was a watershed! It was the convergence of all these different streams of thought. That was when the structure was revealed to me, and how I could hold all the parts in my head. I sent the sketch to my mom, and she immediately recognized it as a triveni sangam—the confluence of three rivers. I was thrilled to work with my niece, the talented Lavanya Manickam, to illustrate my watershed table of contents.

Each section moves like water and is written as a letter. The first is written to my grandfather, the second to my father, and the last to my gentle reader. The epistolary form was very liberating for me. I didn’t want the voice to be preachy or pedantic. I wasn’t interested in having an argument. In the epistolary, I found my voice, which could blend memoir, poetry, reportage, history, and philosophy. I could ask all these big ethical questions and dwell in silence with a trusted reader. I wanted to create a welcoming and generous space for my reader, who I am asking to come along on a grief- and whimsy-filled journey searching for kindness amongst a catalog of sorrows.

Milkweed: Your book covers such a wide range of topics: engineering, family history, animal activism, and, of course, water. Why or how are all of these things interconnected for you?

Sangamithra: I open the book with this declaration: “What you must understand is that when I tell you a story about my body, I cannot separate it from a story about water. And a story about water is about family …” I go on to say that what harms one body harms all bodies. “Like tributaries to the same river, our stories are entwined.”

Water, animals, and engineering are the currents that course through this book. They were also my entryways into different fields. For example, I had studied engineering but wanted to work to better the lives of animals. Offering my engineering skills was how I was able to volunteer at a chimpanzee sanctuary in Cameroon, and that experience led to my earliest published writings.

When I began researching my family history, many things were fuzzy, and I was navigating many gaps in the archive. I wondered if there could be another way into this material. If I could find my grandfather’s engineering records in Burma, perhaps I could use our common background as a bridge to his life. And when I began that search, I stumbled upon stories of elephants, who, like my grandfather, were also used for road and bridge building in Burma. This prompted questions about what it is like to be a subject of empire. When does one submit and when does one rebel?

My body holds the connection between all these subjects, and my experience in each one has advanced my understanding of the others. I am the link, and I wanted to show the expansiveness and possibilities of memoir to capture this on the page.

Milkweed: When I was reading Governing Bodies, I kept catching myself trying to divide the scientific and lyrical parts of it, but what is so moving about the book, in fact, is how these things are actually not treated as separate at all. From your perspective, how might blurring the line between art and science serve us?

Sangamithra: When I was 18 years old, I moved to New York City to attend The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. I loved looking at this beautiful dedication etched into the outer ledges of Cooper Union’s foundation building: “To Science and Art.”

As students, though, we were more often siloed in our disciplines. We declared ourselves engineers, artists, or architects when we had yet to discover who we were, what we were capable of, and what other fields could offer us. It was in our humanities classes where we would all come together. Many years later, when I pursued an MFA in creative writing, I found that there, too, we were separated by discipline—this time between nonfiction, fiction, and poetry.

As a practicing engineer, I often struggled with compartmentalizing different parts of my life. I would have a day job and carve out space for activism and writing on nights and weekends. I knew all these parts of me were connected, but it was challenging to find ways to integrate them more fully. What I came to realize is that every experience I’ve had in one field proved meaningful in unexpected and delightful ways in other contexts.

Writing this book allowed me to bring all of myself to the work and open myself up to the possibilities. Governing Bodies dwells in that liminal space between art and science, poetry and prose, and personal and planetary grief. I am drawn to the confluences of these subjects and approaches because I believe that is where we find connection, insight, and understanding.

Milkweed: Can you talk about your relationship with place and how it felt to interconnect places across multiple continents in this book through writing?

Sangamithra: I began this project with a search for one place in particular—Kallakurichi. This was

my father’s birthplace and the site of my grandfather’s activism at the bend of the Gaumukhi River in Tamil Nadu. It was a place that was both real and imagined, full of mythology and lore, and each year, I was losing more people who still remembered it.

My grandfather had quit his engineering post with the British in Burma to become a water diviner in Kallakurichi to bring water to those who had been denied access due to the cruelty of the caste system. My father and his siblings grew up in this ashram that was modeled after Sabarmati. I was interested in these attempts to disentangle ourselves from systems of harm.

I write that “Kallakurichi is an origin story, a beginning, a chosen ancestral land, an idea, a moral philosophy, a refuge, a refusal.” What Kallakurichi is and means to me kept evolving and expanding through the course of writing this book, which became not only a search for this specific place, but the search for a radically kinder world.

I trace my grandfather’s footsteps in 1920s and 1930s Burma in search of what it was that led him to his Kallakurichi. I realized that I was searching for my Kallakurichi too, whether it be in New York or in California, in the forests of Cameroon or the mountains of Rwanda, in a slaughterhouse in India or the limestone cliffs of France.

I begin again, and again, searching for my own Kallakurichi across the world.

Milkweed: Can you talk more about your work in animal rights? Why did it feel important to add that component of your life into this narrative?

Sangamithra: My book is about how we sit with sorrow on these planetary scales, and animal activism is where I first started these kinds of practices. It’s a lyrical reckoning of how we live with the legacy of historical harms across all bodies—and how bodies are controlled and liberated. Animal rights is where my courage comes from and where my sense of justice was first formed. I feel my concern for animals is a kind of inheritance from my father. I learned at a very young age the importance of advocating for what you think is just, even and especially when it is unpopular, and to continue to do so, even and especially when victories are few and infrequent.

The book explores my experiences thinking about animal lives, from being president of my animal rights club in high school, to protesting dissection and vivisection, to volunteering at various primate rescue sanctuaries, to bearing witness inside slaughterhouses and animal factories, to pondering how we can peacefully coexist in cities. I write about a very special time in my life when I worked at Satya magazine, a New York City–based publication that explored the intersection between animal advocacy, environmentalism, and social justice. I wanted to contribute to the history of that place and time by being part of this activist/writing community which was its own special urban ecosystem.

As a reader and writer, I am very much interested in how our lives are entangled with the other species with whom we share our world, and how we capture their lives and these entanglements on the page, which led me to start The Literary Animal Project. I am interested in how we write fully about animal lives and agency. How do we create art that moves beyond reverence, toward a radical reimagining of our relationships?