Listen Here: National Poetry Month Special (Part Two)

Hello again, friends! It’s time for round two of our National Poetry Month feature (check out part one here).

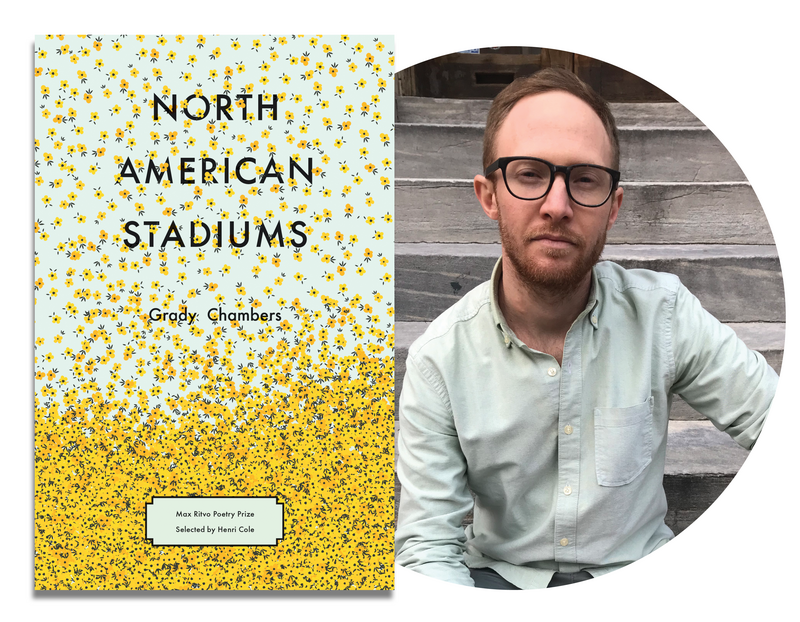

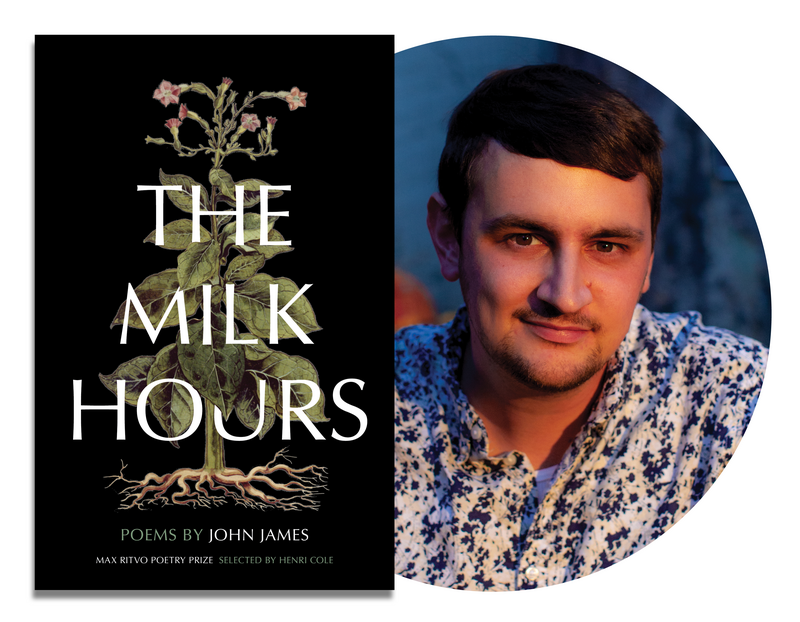

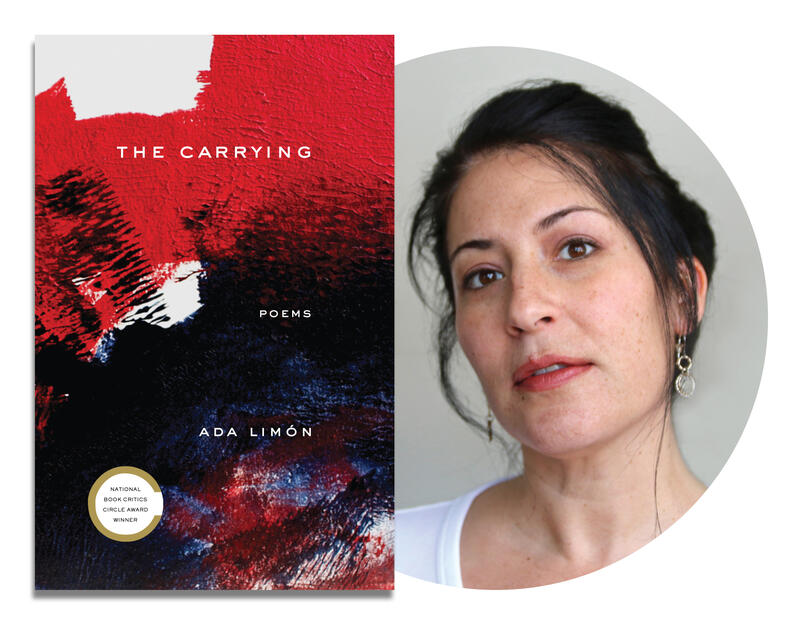

For our second installment, I touched base with a few well-loved poets whose books are entering the world again as paberbacks. I’m thrilled that Grady Chambers, John James, and Ada Limón shared their thoughts (and voices) with us to discuss the process of putting together a poetry collection, as well as the power of poetry-out-loud. Listen to audio of them reading from their collections below!

Note: for best listening experience, please use Google Chrome.

“A Story About the Moon” from North American Stadiums

Bailey Hutchinson: I often think—both as a writer and as a reader—about the “project” of a poetry collection. For some it seems like the shape of a book becomes slowly visible in a body of work—like a facial feature we didn’t clock until we spent a long time looking in the mirror. But sometimes the idea of the book exists long before the poems that make it. Which was the case for you?

Grady Chambers: With North American Stadiums it was definitely the former—the shape of the book emerging naturally from a larger body of work (I love the way your question articulates that experience). At a certain point around 2016, I realized I was sitting on over 100 pages of poems, and began reading back through them to see if I sensed the shape of a book among them. That was how North American Stadiums got its start—I pulled poems from that initial pile that I thought were all, to different degrees, orbiting around a common core, and began to order them. In doing so, I saw that there was a larger story the individual poems were adding up to, a larger narrative arc. And that’s been my experience as well with the manuscript I’m working on now. I feel that if you give yourself enough years, the poems you write across those years almost can’t help but come to tell a larger story.

BH: Some (okay, it’s me, I’m “some”) would say that teaching poetry-reading (as in, reading a poem out loud) is as important as teaching poetry-writing (as in, committing words to the page). And some might also say there’s a distinct power in poetry as an audible experience. This is a long way to ask: what goodness does hearing poetry carry for us, right now?

GC: The goodness for me in hearing a writer read their poem out loud—rather than just encountering it on the page—is the opportunity to experience the poem’s music and sonic qualities—its rhythms, its pacing, its pauses, its different emphases at different places—as the writer intended or hoped for them to be experienced. I imagine most writers “hear” the poem they have written in a very specific way—they know the pace they want for it, they intricately know its pauses and emphases, and the listener gets to really experience the writer’s full intention and vision for the poem when they get to hear the writer read it aloud. So, I love that. Also, hearing my poems aloud has always been an important part of my writing process, particularly with the poems in North American Stadiums. When I would finish a draft of a piece, often I would record myself reading it aloud. I would then play the recording back to myself. I felt l could tell where the poem needed work based on when I sensed it lost its rhythm / momentum. In that sense, hearing poetry has not only been “good” or pleasurable, but also helpful to me in my writing.

“Kentucky, September” and “Erosion” from The Milk Hours.

Bailey Hutchinson: Sometimes the idea of the book exists long before the poems that make it. Which was the case for you?

John James: For me, it was both. That is to say, the project only became visible over the course of many years, through a long process of trial and error, building and cutting—making and unmaking. But in a way, the book was inevitable. In fact, I’d have maybe preferred not to write it, or rather, not to have written about some of the more sensitive subject matter. I circled around my father’s suicide for a long time, writing poems that danced around that fact but never spoke it. Some of those poems are in the book. I’m thinking, for instance, of “Years I’ve Slept Right Through” and “Clock Elegy,” and some others. Ultimately, though, it had to come out, and the poems most central to that fact—especially the title poem—insisted not only on their own being but on their primacy within the collection. “The Milk Hours” had to be the opening poem, just as it had to be the title. I resisted it, actually. In the end, the poem demanded to be heard, so I let it speak.

BH: What goodness does hearing poetry carry for us, right now?

JJ: Poetry has its roots in the oral tradition: in traveling bards memorizing or improvising verse in front of an audience, sometimes to musical accompaniment. There’s an amazing moment in the first book of The Odyssey, for example, where Homer describes a bard singing to the hall of suitors, who’ve come to court Penelope. The move is self-reflexive: Homer, or the assemblage of traveling bards to which we ascribe the name “Homer,” is referring to himself and to the social conditions of his own creativity. To bring this to the present: whether written for the “page” or “stage” (a dichotomy I detest) poetry maintains an undeniable sonic quality, one that demands to be heard aloud. Even within the private space of the lyric, poetry’s aurality opens the potential for semantic play. How do you pun without sound? But even more essential is the rhythmic quality of poetry, which mimics—we might even say performs—functions of the body, the movements of the lungs and heart. This embodied affect comes alive when we read a poem out loud, and when read in the midst of other people, it manifests a shared or communal embodiment, which literalizes the frequent anatomical metaphors we employ to describe groups of people: the body politic, the army corps, etc. As communities, we view ourselves as bodies, together. In this moment of physical distance, I imagine we need that sense of communal embodiment more than ever.

“The Raincoat” from The Carrying

Bailey Hutchinson: Sometimes the idea of the book exists long before the poems that make it. Which was the case for you?

Ada Limón: The Carrying came to me slowly. I had to write many poems in the book with the idea of not publishing them at all. I needed that sense of freedom, the idea of writing without an audience, a reader in mind. And so when the poems started to come together, started to talking to each other, and when I felt ready to share a few of the individual poems in the book, then suddenly I realized a book was coming together. Then, I asked myself, “What does this book need? What am I leaving out? Where am I letting myself off the hook? Where is the praise? Where is the grief? Are they balanced in a way that feels true to my experience in this body right now?” When I asked myself those questions, soon I could write additional poems that spoke to the larger questions of my life at that time. The Carrying, like most of my books, wasn’t a concept, or an idea before the individual poems came to me. For me, the poems always come first, slowly and privately, and then suddenly I realized something was happening, a book was being made. It’s a great gift to witness that moment and I take the making of a book very seriously. I have to honor it once I see it forming.

BH: What goodness does hearing poetry carry for us, right now?

AL: I love reading poetry out loud, and I love experiencing poets perform their own poetry. I think that’s because poetry, for me, ins an experience of the whole body. It’s not just in the mind. If the body can engage in the poetic experience, then it feels like the poems is reaching its most complete form. For Deaf people or hard of hearing people that might mean signing the poem or experiencing it being interpreted into Sign Language. Poetry feels like it should live in the senses, in the physicality of reader. The fullness, the roundness, the wholeness of a poetic experience includes breath and so however poetry can find its way to alter your breath, that’s where the magic happens. Reading poetry to yourself is beautiful and intimate as well, but when you love something, when it reaches you deeply, we want to put those lines or words in our body, we want to hold them close like our own life-giving air.