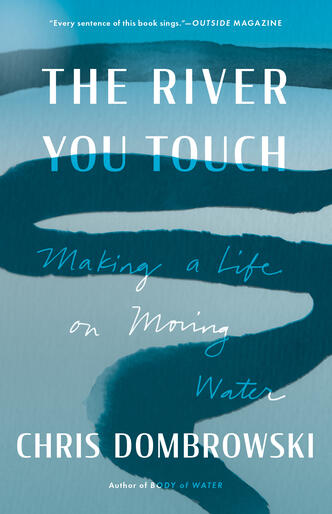

Surrender to the current; on writing to survive grief, finding comfort in one’s hybridity, and resisting the urge to write like Rimbaud

Chris Dombrowski is the author of The River You Touch: Making a Life on Moving Water. He is also the author of Body of Water: A Sage, A Seeker, and the World’s Most Elusive Fish, and of three acclaimed collections of poems. Currently the Assistant Director of the Creative Writing program at the University of Montana, he lives with his family in Missoula.

In the following interview, the famously personable hybrid-author made a stop in to the Milkweed Editions offices in Minneapolis, MN in the midst of touring for his new book, which has just been named a finalist for the Montana Book Award. He’s been to the Twin Cities no shortage of times as a beloved collaborator, speaking at events as various in range from cozy author readings at our brick and mortar bookstore to guest speaking at our Book Lovers Ball in 2016. As our in-house Editor & Storyteller, I was personally intrigued to learn more about the story of the man behind the book: a poet, a memoirist, a creative writing program director, a fly-fishing guide, a husband, and certainly not least of all, a father to the three children who just so happen to have inspired his latest book.

Milkweed Staff (MS): You’re an author, a fly-fishing guide, and a creative writing professor at the University of Montana, in addition to being a husband and father to three children. How are you able to set aside time for your art? Is there an intentional practice for setting aside that time, or does your art sporadically weave its way into the undercurrent of your day-to-day?

Chris Dombrowski (CD): To answer that question, I’ll share this story about how some poems came to be last winter: a dear friend of mine, this drummer named Billy Conway, passed away a couple of days before Christmas. At that time, I’d been working for a few years on what I’ll call the final draft of The River You Touch. I’d been making great progress on the book, and then we hit this inevitable pandemic gridlock, where we’d been bouncing things back and forth with some consistency and then everything kind of stoppered. All of that is to say, I hadn’t been working on poems for a long time, I’d just been working on The River You Touch from about the end of the pandemic—spring—until last year. And then right as I was about to finish, my friend passed away, and suddenly, these poems started coming to me in ways that poems never do. Usually it’s a seed or an image or a sound, and then the poem grows out of that, but these poems were coming almost fully intact as if I was taking some strange dictation or something. And I knew pretty soon after they were born that they were helping me survive the grief. In that sense, the necessities of survival verged me off into a different path in that moment, which is something that can happen.

A photo from Chris Dombrowski’s “writing shed” back in Missoula, MT, filled with stacks of manuscript drafts for The River You Touch.

When I’m working on a specific project, my practice is going to the work daily. I have this little shed in my backyard, a little 12x14—studio is an overstatement—that has a little bunk up top above the desk and a little heater and electricity but no wifi, and I can slip out there for a few hours a day and get it done. But that same feeling I was talking about with the poems that I wrote last winter, I had that initial feeling when beginning to write The River You Touch. I had written a few sign post essays by then that were kind of stewarding my voice as a prose writer, one of which was subtitled, “The Nature of Wonder,” and that was the original, ultimately jettisoned title; but I had to give myself over to the story before I understood where the book was going. How do I do it? I don’t know—time-wise, it doesn’t add up.

MS: It feels as though there’s these multiple different lives that are all cramming their way into one existence—The River You Touch somehow gracefully hints at that as well.

CD: It does feel like that. But when I’m not writing, I don’t write. I know that sounds simple, but this fall, with the new book out, and with the school season being as crazy as it is, I’ll make some journal entries here and there but that’s it. In the olden days, if I wasn’t writing, I’d be pretty awful to be around because I’d be upset and angsty all the time. But now, I don’t want to say I’ve given in to the reality of life, but I’ve tried to just be present for all of that and not always be worried about a piece of writing I’m working on. It gets tiresome to be around, and no kid deserves a writer for a parent, so I think, when you have kids, you have to just dissociate from that as much as possible.

MS: Would you say your relationship to urgency has changed, then, and in some ways deepened? It seems like you’re describing a new urgency for the present and to whatever life has conjured up to the surface for you. And it’s less about this idea of a construction of a timeline.

CD: Very much so. I think there’s an urge for the young writer to be like—

MS: Relentlessly prolific?

CD: Yeah, or to think, like, “I have to be like Rimbaud and write this book at age 18 that eclipses everything in its path.” I’m 46 now, and, it didn’t happen. I didn’t write that book. But what does my journey as a writer look like today? I’m staying present to the stories that surround me, the untold stories in my own personal sphere, which interest me more than being Rimbaud, anyway.

MS: Speaking of the stories around you, there’s a unique friendship and interdisciplinary collaboration between yourself and the musician Jeffrey Foucalt that’s enabled your work to have a gorgeous second life as an audiobook. In your preface, you write, “Listening refers to direct contact, engagement, what the forager Jenna Rozelle calls, ‘the primacy of immediate experience.” I was hoping you could speak to that idea as it relates to listening to an audiobook, and I’m also curious to know what you feel the experience of listening to your work in particular, versus reading it, will offer.

CD: It is a magical collaboration, and really, one of the coolest things I’ve ever had happen as an artist and a writer. One of the things most commonly expressed is this notion of the kind of vivaciousness of the language of the book paired with his fairly mellow approach to the prose. So his delivery is much less volcanic, say, than mine. As a speaker and reader, I’m very expressive and there’s a lot of this—[waves hands emphatically], whereas Jeff is way more composed in a way, which you would expect from a skilled performer. And I think it’s wonderful to have those seemingly disparate things working together.

I also love this idea that you’ve brought up in regards to Jenna’s quote, because when I read a book, I’m a proficient reader, and I can do five things at once. But when you’ve got on a pair of headphones and you’re listening to this audiobook, there’s an opportunity for deeper engagement with the language. And I love it, too, because as a poet…poetry is a bodily art, and it’s experienced in the body first because it’s meant to be read aloud. So the notion that something similar could happen with an audiobook, that an audience could have a bodily connection to it, especially because the prose has a lyrical quality to it—it’s really special.

MS: There’s definitely an evocative, immersive quality to your language. It’s sort of winding and serpentine, it’s flashing in and out of memories of the past, vignettes in the present, wilderness, and family—it parallels the movement of water, which is the thing you’re clearly so drawn to. It feels like water is your muse, but it’s also your form.

CD: Thank you for saying that—form following function is something writers always aspire to, but it’s a different thing altogether to hear it expressed that way.

MS: In some of your passages, you depict a wordless realm of flora and fauna and water—but then there are these passages, too, where you’re amongst friends in the backcountry of Montana, and it feels like a different universe. Running parallel still, your carefully crafted language reminds me that you’re deeply immersed in the worlds of art and academia. What is it like straddling these parallel universes—some of which seem to be effortlessly intuitive, while others are more instructional? Is there an element of code-switching required in these cases?

CD: The answer to that question is about 25 years in the making. Today, I’m very comfortable in my hybridity. But the opening narrative of my book takes place back in 2004, and that version of me was way more uncomfortable with it all.

When I was in my late teens, I was crazy about a book called A River Runs Through It by Norman Maclean, and there’s a great old interview for The American Audio Prose Library where he’s asked, “What was it like for you, going from the woods of Montana where you spent every summer to the University of Chicago every school year where you taught Shakespeare?” And he said, “It was a recipe for Schizophrenia, but I was determined not to let it happen.” And, I think, not to be melodramatic, but I felt a certain sense of schizophrenia between going to the river and making my living there for several months at a time and then coming back to the classroom or the desk. Making one’s living on the river, too, is fraught with complexities because when I was first starting out, I was often in the boat with people I didn’t care to be in a boat with. It took me years to establish a clientele that are basically made up of friends, which allowed me to make that endeavor more of a vocation or a calling. And then, as those relationships grew, people would say, like, “How’s your writing going? What’s your role at the university?” So over the course of 20 years, seemingly, that recipe for schizophrenia, if you will, became way more harmonized.

One of the realizations I experience in the book is that ultimately nothing is separate from anything else. We compartmentalize to survive, right? But we know that reality—the world—is completely interdependent. And so, that kind of confluence or coming together of those lives, and of becoming a parent…There’s no way you can live three separate lives, but you can live one life that allows those three existences to come together, if you’re accepting enough of that reality.

MS: I’m curious if you feel a similar sense of cohesion between your poetry and prose, despite what some would perceive as a total separation of genre and form throughout your published works. Was there a learning curve for you in the journey from one genre to the other?

CD: There’s definitely a learning curve for me in long-form nonfiction, and I feel like I first became addicted to it when I was working on Body of Water—in particular, when I began working with Daniel as my editor. Not to sound overly confident, but I began to feel a certain level of competence with the poems I was writing. I have an image—something that instigates a poem—and I can pretty quickly grasp what a good form for the poem might be, and it was like I was in a rut. Whereas when I started writing nonfiction, the learning curve was so steep and I fell in love with the challenge. For better or worse, my motto has always been, “If it’s the easy way, it’s probably the wrong way.” So the learning curve you mentioned actually attracted me to the long form. And once I fell in love with that, I wanted to find a way to make the prose as musical as possible while still retaining absolute clarity and meaning.

MS: So does it feel like you’ve found this place, this language, which is your language, that’s a kind of perfect confluence between both forms? It’s the musicality of your poetry, and the shape of your prose?

CD: It does feel like that for me. And I think, there’s much to be learned still, but I have an aspiration towards it. I feel like there’s more discovery for me in prose than what I was able to attain in poems. Which is not to say I won’t end up back there again, I’m sure I will—but I felt like I could see a poem, read three lines and think, “Okay, I know the effect this is going to generate in me before I’m even halfway through it.” And that wasn’t the right place to be in, whereas I feel way more lost in a field in a book of prose, and I love that feeling that, “The dog is out searching in a field, and the field is vast.” What is it going to find?

MS: And I think that comes across in your book, too. That sense of getting swept up in a current, of surrendering to it, feels delightful and intentional. What else are you hoping readers will discover in your book?

CD: I mean I hope they find a sense of wonder regenerated in themselves. I hope the language, number one, ignites that faculty in a way. Going back to that Jenna Rozelle comment, one of the things I wanted to attempt, even though it seemed impossible, was to create in each sentence as much direct contact with the natural world as possible. I know that seems almost backwards because it’s the written word, and you’re holding a book, and you can easily just go out and touch the river, to pull from the title—but I really felt like if the prose was alive enough, it could make tangible the natural world. It’s our main conduit to reigniting our sense of wonder, and if that’s reignited, we perhaps stand a chance of protecting it. The narrative takes us to a point in time where that reality becomes lost to the narrator, and it’s not until his children revivify it in him that he realizes the voices of the natural world can have more resonance than the voices in one’s head.

MS: In your saying that, it seems clear how the aims of your book and the ethos of Milkweed Editions feel stunningly aligned. There’s so much care in your words and in your work to share the beauty and sacredness of this more-than-human world, and you make a compelling case to protect it at all costs. I’m wondering if you can speak a little bit more about your journey to and with Milkweed, and how you realized it was the right home for your latest two books, my first point potentially notwithstanding.

CD: Obviously I’ve always loved the books that Milkweed publishes, and as a writer, it was a dream house for me. The first time I’d ever considered bringing something to Milkweed was back in 2012, and I’d been working on a series of essays on the Bahamas and this central character, David Pinder, that I had no idea what to do with. Milkweed began stewarding my work way back then, and they told me when they agreed to work with me that they didn’t just believe that it would become a beautiful book; they also believed that I was the type of writer whose career they wanted to help along the way. It started a magical relationship for me with Milkweed, both from an editorial standpoint and from a community perspective. The kinds of opportunities that have come to me because of my association with Milkweed are myriad, and when I tell other authors I know about my experiences with Milkweed—maybe they’re at other, bigger publishing houses—they’re blown away by the level of attention and support each book receives.