Surviving One Breath at a Time: Celebrating the Launch of Creature Needs

On February 27th, Milkweed Editions and the University of Minnesota Press hosted a book launch to celebrate Creature Needs: Writers Respond to the Science of Animal Conservation, in collaboration with the nonprofit organization Creature Conserve.

“Before we read, I want a moment to breathe with you.”—Claire Wahmanholm

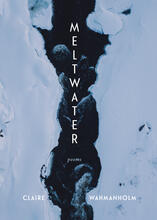

“Before we read,” Claire Wahmanholm—author of Meltwater and—began, “I want a moment to breathe with you.” Under her instruction, she coaxed the crowd into a gentle meditation of hummed breath. Within three exhales, she transformed the room into a living, vibrating singing bowl. By the final round, the audience was energized into a thrumming beehive. Already, she demonstrated a basic ‘Creature Need’ that their polyvocal collection aims to address—that we need air, food, water, shelter, room, and each other to survive. “I was assigned ‘shelter,’” she explained and, between breathwork and community, her essay is the first to break the night open.

After, Charles Baxter—author of Blood Test: a Comedy and The Feast of Love—set forth the question, “how many of you have seen a firefly?” A scatter of hands lit up in the spotlight, Claire Wahmanholm included. “Now,” he said, crooking his head, “how many of you have seen one in the past two years?” Slowly, those same palms slipped back into shadow. In two questions, he has personified the disappearance of fireflies as immediate as our own empty hands. Pivoting, he described the dying light of glow worms. How, in their manufacturing of artificial light, it can undermine the glow worm’s chances of attracting a mate. “We are so concerned about losing the light, what happens if we lose the darkness?” Then, he tilted our axis from ground-level to the entire sky, from disappearing fireflies to fading stars amid light pollution. For his prompt ‘Air,’ Baxter intertwined these vanishings until they were interchangeable extinctions. On stage, he inflated the microcosm to the macro, in which species and supernovae alike are falling together at the same, rapid pace.

“We are so concerned about losing the light, what happens if we lose the darkness?”—Charles Baxter

Next, Kimberly Blaeser—previous Wisconsin Poet Laureate and founding director of Indigenous Nations Poets—lit the presentation screen aglow, all grin and coiffed hair. Stuffed bookshelves lined the background. At her side, a table towered with journals. Also tasked with the prompt ‘Air,’ she explained how her mind initially drew to birds but, as she wrote under the looming threat of wildfire, her creativity crackled toward combustion. By the time the fire, known as the Greenwood fire, consumed twenty-five square miles and forced the evacuation of three-hundred homes, she explained, she pushed away from her desk, stricken. “How can I keep working when everything is aflame?”

“How can I keep working when everything is aflame?”—Kimberly Blaeser

From there her voice lilted into lyrical stanza, conjuring images of embers igniting—a reversal from those fading fireflies. “How do we chart it,” she asks, describing her action from witnessing, evacuating, then documenting, “the cartography of story?” In a poetic twist, the birds’ absence mirror reality. Among the first evacuees of every natural disaster, they detect subtle shifts only perceptible from their view and senses. By the time rising smoke signals danger to us—the birds are already gone.

Next, Sean Hill led the crowd from smoke plumes to a tower of ever-sharpening poetry, his name a serrated peak. His prompt is immediate as his poem renders the shape of ‘shelter’ itself. Hill’s voice, velvet and baritone following Blaeser’s birdsong timbre, filling the performance hall with the different forms of shelter. Afterward, Hill shocked the audience by peeling back his editor’s curtain by scrolling through endless drafts and revisions of this singular poem—all twenty-six pages. To the awe-struck audience, Hill shrugged his shoulders and grinned. “I was just trying to follow the sonic thread and resonant language,” he says, revealing the poem’s sharpening evolution. “It was just working itself out on the page.” A self-described ‘physical’ writer, he broke up drafting by mounting his bicycle and coasting through town. During this ride, he described, he came upon a pike that an encampment sought shelter within after being pushed to the cusp of the city. “That was it,” he recalled, taking in the scene. “That’s the poem.”

“I was just trying to follow the sonic thread and resonant language. It was just working itself out on the page.”—Sean Hill

As the performance closed, the four writers circled back to the core of Creature Needs by calling on viewers to harness the power of science and literature. “Scientists and poets are both drawn to that same sense of mystery in ourselves and in the universe,” Blaeser said, her voice wistful, “they just walk toward that mystery in their own ways.”

“Scientists and poets are both drawn to that same sense of mystery in ourselves and in the universe, they just walk toward that mystery in their own ways.”—Kimberly Blaeser

Balancing the heaviness of vanishing species and forced evacuations of animals and encampments alike, Claire Wahmanholm peppered the conversation with light quips and drew us back to mindful breath. This cohort of Creature Needs urged readers to re-center attention back to the basic needs we all need to survive—air, food, water, shelter, room, and each other. In this partnership between Milkweed Editions and the University of Minnesota Press, the authors of Creature Needs lightened the weight of survival one shared breath at a time. For more on Creature Needs: Writers Respond to the Science of Animal Conservation and the minds behind it, we invite you to learn more here.