The Company of Owls: Author Q&A with Polly Atkin

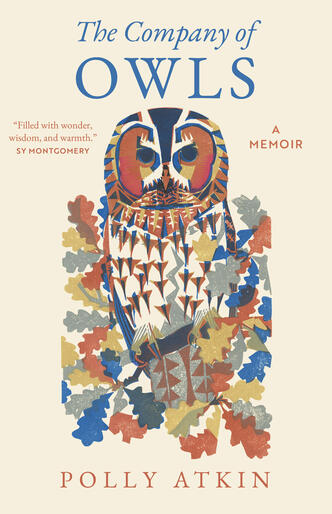

In anticipation of her forthcoming memoir Company of Owls, we sat down with author Polly Atkin—recently longlisted for the 2025 Wainwright prize—to discuss the kinds of company we keep, the habits that hold us steady, and the birds that transform our journey along the way.

I try to be a good neighbor to humans and nonhumans alike, mindful of community both present and future.

Milkweed staff: We were delighted to discover that you own the independent bookstore, Sam Read Bookseller! Living alongside the owls, how have they informed your place within the community—both as a bookseller and as a neighbor?

Polly Atkin: It’s a strange thing finding yourself at the helm of a shop that has been at the center of your village since 1887. It holds so much history and has seen so much. It means so much to so many people, it’s a great privilege and responsibility to be carrying that forward. Because it is right in the heart of the village, the shop often functions as an unofficial information and gathering point. My partner Will got to know so many people through working there for so long, and it’s really important to us that as a business it serves the local community and supports local creativity and learning as well as visitors. Because the shop doesn’t have a backroom or store-room, and is open seven days a week, we spend a lot of time after hours doing admin and sorting work, shelving and restocking, managing orders and doing shop maintenance. As well as the tawny owls who live around our house, there’s a whole cluster who live almost opposite the shop, so often we hear them when we’re shutting up the shop. They’re really linked now in my mind – coming out of the shop late, or on an autumn afternoon, and hearing the owls. I try to be a good neighbor to humans and nonhumans alike, mindful of community both present and future. I suppose there’s a similar feeling—the bookshop and the owls have both been here much longer than I have, and know much more than I do. But I hope I can help make sure they will be here for many generations more to come.

Milkweed Staff: One of your most striking sections of the book, “Uplokkid,” reckons with the pandemic. To quote a passage, “I was thinking a lot—as many people did in those weeks—about solitude, about aloneness, about separation and isolation and the subtle distinctions between those states.” What does isolation mean for you, now?

Polly Atkin: Living with chronic illness, I was already used to a certain degree of isolation before the pandemic. But the pandemic changed my relationship with socializing. As I write in the book, I love company, but being in it takes a heavy toll on me. Now it’s complicated by not being able to risk catching covid, and so much of the world having moved on as though it’s no big deal anymore. I’ve realized that people who have only met me since 2020 don’t know how much I used to love a party, how I’d always be the last to leave. There are so many things and so many people I miss now, not because I couldn’t do them at all, but because not enough people want to adapt activities to be covid safe or recognize that there is still a risk, not just to people like me who know how it could affect them, but to them too. There’s much to appreciate and enjoy in the different kind of life I’m living because of it, but there is sadness and loss too, especially around special occasions.

Milkweed Staff: In your memoir, Some of Us Just Fall, you touch on Henry David Thoreau’s observations living alone in the landscape near Grasmere, that “he lived in a state of separation but not total isolation, keeping, as he tells us, three chairs: one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.” How do you find yourself working in conversation with Thoreau or other writers in this second memoir?

Polly Atkin: Writing is itself a way of being together in thought if not in place, and to me that includes bringing community into my writing. It’s important to me to bring the voices of people who have influenced me in my thinking directly into my writing, as well as people I think in some way or other I am following in the wake of, whether they are contemporary writers or long dead. The Lake District as a place is so steeped in literary history I think it’s almost disingenuous to write about it without acknowledging the writers of earlier generations, but I think it’s also really important as writers – especially nonfiction writers – to acknowledge and include our contemporaries. I owe so much to writer friends who are rarely in the same place as me but are with me in my thoughts and my ways of thinking.

Although I’d been writing about them, I hadn’t thought they would become the main characters, but I’ve realized that’s a pattern in my books now, that something in the background will become central in the next. They are all concerned with my life in Grasmere.

Milkweed Staff: The presence of tawny owls arrived as early as the first chapter of Some of Us Just Fall—which prompts me to wonder: did you always feel the owls’ and their story waiting within you, even then? How do you see your two books in conversation with one another?

Polly Atkin: Definitely yes, on both counts. The owls have always been part of my life in Grasmere and their calls are part of the soundtrack to it – they’ve appeared in so much of my writing even if just in the background. When I started to see them more regularly after I started freelancing, and often working from home, in 2017, they became even more part of it. I was already writing poems about some of the owls who appear in The Company of Owls – particularly the owl I call “Lockdown Owl” before I began work on the book. In fact, it’s one of the reasons my agent knew I might be able to write a book about owls when the topic came up in a chance conversation with my UK editor, Sarah Rigby. Although I’d been writing about them, I hadn’t thought they would become the main characters, but I’ve realized that’s a pattern in my books now, that something in the background will become central in the next. They’re not direct sequels, as such, but they are all concerned with my life in Grasmere. What side characters from The Company of Owls might become the central narrative next, I wonder!

Milkweed Staff: As you’ve explained in Company, “so often we associate owls with fierceness, with the hunt, with brutality and with death … in some cases, we also throw in wisdom.” What do owls mean for you right now, in this current moment?

Polly Atkin: Owls do carry extraordinary knowledge, but it is the knowledge of any species that has survived and adapted over such an incredibly long time. Owls have been found in the fossil record of the Paleocene, 61 million years ago. I think maybe we feel that in the uncanny shiver when we hear them sometimes – we’re feeling that vast stretch of time – that they were here long before us and may be here long after us. That’s what they mean to me right now – continuation. And as always, when they’re calling around the house in the dark, company.

Milkweed Staff: Particularly in the wake of Raynor Winn’s controversy—and in light of your recent response against ‘nature as cure’ in Literary Hub––what are you hoping that American readers take away from Company, both as a nature memoir and as a portrait of what it means to live with chronic illness?

Polly Atkin: I hope people understand the ongoingness of chronic illness – that there are no simple solutions or none of us would be ill. But also that disabled lives are of just as much value as any lives. That a disabled live can be rich and full of joy. That disability is part of nature, not an aberration to be eradicated. I hope people also can be reassured that there are many ways of being with and living alongside nature. We don’t all have to be hyper-fit and living off grid like an adventurer to feel that daily companionship. It’s about attention to what is around us, not being in any particular place or body.

I think so much about the sole spotted owl I write about in the book, the last of their species living in the wild.

Milkweed Staff: In “Onlihede” you allude to the vanishing of certain owl species, which I’ve pondered ever since finishing your memoir—what are your thoughts or shifting views on the state of dwindling owl species since first publishing Company?

Polly Atkin: No species of owl should be at the brink of extinction because of human activity, directly or indirectly, and it’s heart-breaking that so many are. I think so much about the sole spotted owl I write about in the book, the last of their species living in the wild. How they call out for a mate, and no mate can come, because there are no others of her kind left.

Milkweed Staff: For the bird watchers who will be delighted to come across several owl species in Company, from tawny owls to great horned owls, I’m wondering if there’s an elusive species out there that you’re hoping to see one day?

Polly Atkin: Oh! So many. At the time of writing I still haven’t seen a long eared owl in the wild, which I would love so much. I’d obviously go wild to see some the rarer ‘unofficial’ residents or visitors to the UK, like a snowy owl or eagle owl. But there’s so many around the world I’d love to see. I used to have a real soft spot for burrowing owls, and I’d love to see a great grey owl in its own territory. But I think what I’d love the most to see is a northern saw-whet owl. Their faces are just amazing. Any owl is a good owl to me, though!