The Long Game: Balancing Medicine and Ceremony in the Western World

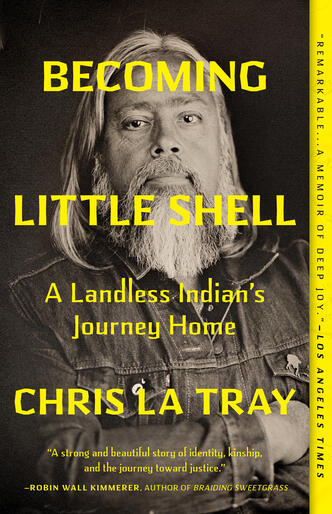

On March 18th, Becoming Little Shell author Chris La Tray partnered with Milkweed Editions and Bimosedaa—a supportive, culturally-relevant housing program serving vulnerable indigenous populations in Minneapolis—to tour their on-site location.

“Bimosedaa, it’s Ojibwe for ‘let’s walk together,’” Program Manager Heather Day says, welcoming Chris and Milkweed staff into their apartment-style housing program. Around us, sunlight filters in through sloping glass walls.

“Bimosedaa: It’s Ojibwe for ‘let’s walk together.’”

True to their namesake, Chris and Heather radiate into the very embodiment of the phrase. As they drift past tenant rooms and gathering spaces, Heather gestures to a traditional star quilt framed along the wall. “When we designated this room for therapy, we received it as a donation to honor it. It feels perfect here, doesn’t it?” Downstairs, Heather high-fives every other guest, checks in with everyone, and ensures that the halls remain barrier-free for those with special accommodations. Though most tenants are shy, one resident wheels his stereo into the common area, all laughter and R&B. When the song fades, he slips off his shades and cradles his beaded medallion, smiling at Chris. “What brought you to Bimo?”

At this question, the air shifts—one in which both passions between two creatives are lit and shared. Chris talks about life as the Montana Poet Laureate, exploring ways to write every day, and touches on his book, Becoming Little Shell. When the resident delves into his own story, Heather disappears with a knowing grin, returning with three giant canvases. “Since he’s been here, we’ve helped him get into painting again. In fact, we’re auctioning off one at our upcoming gala.” One by one, she displays his work along the wall—a line of tipis trail smoke along the canvas borders, a ghostly figure in a headdress fills a night sky. Beneath the figure, a blanketed woman cries a river into the bottom of a canyon. “This is just what I could do since coming here, of course,” he says, his voice softening. “Before, I used to paint with whatever I had. Expired juice, berries. I’ve even used coffee.”

For the “Irritable Métis” storyteller, Bimosedaa’s mission mirrors the same battle for belonging, restoration, and surviving within a system seemingly pitted against them. La Tray, too, has advocated endlessly about his tribe’s hard-won battle for federal recognition. That evening, as he takes the Milkweed stage to the tune of guitar riffs, it is no different. “We were known as the landless Indians until we were restored in 2019,” he begins, stepping away from the podium to speak directly to us. “We’d get knocked down and stand right back up against a system designed to eliminate us.” Here, I almost see his eyes flash to that afternoon in the sun, trading stories with a painter who created art by any means necessary. “We are a symbol of what happens when we play the long game.”

“We are a symbol of what happens when we play the long game.”

To prove his point, he weaves a resonant thread between the past and present with the Cree Deportation Act of 1896, reminding us that we have always fought these battles. “So many folks like to say ‘we just don’t have the words to describe what is happening,’” he says, his voice mockingly stern. “But the words have always been there, whether it was in Cree or Anishnaabe. Just because the majority have forgotten, doesn’t mean we have.”

As his Milkweed event draws to a finish, the room alights in a fury of questions. When asked, “how do you find balance between traditional medicine and ceremony with the western world?” He braces back a laugh, amused. “Well, I do whatever I can to avoid western treatment,” at the slight gasp from the crowd, he sighs, digs deeper. “I try to balance it where I can. I ground myself through nature—things like rocks, the land, trees, the spirits of all my relatives.” Here, a glint of knowing flickers in his gaze as he hints toward his latest work-in-progress on the more-than-human world. “That balance is all around us. We’ve been disconnected from it. We just have to find it again.”

At this mention of disconnection, Chris fields tough questions from the crowd, though he fires back with kindness, careful consideration, and always with a punch of humor. Here, again, he shows the long game in action. “The problem was never about feeling disconnected with the land,” his eyes skate across a vast field of memory. “Sometimes, as I’m driving across state lines for events and I’m coasting along thousands of miles through the plains, I can’t help but think to myself, ‘Why did they have to take all of it? Why wasn’t there any room for us?’”

“Why wasn’t there any room for us?”

This fine balance between medicine and ceremony—between the western world and the indigenous one—follows Chris from Milkweed and into the 41st Minnesota Indian Education Association Conference where, on the penultimate day, news on the closure of the Department of Education notifies all 1,000 Indigenous educators at once, sparking a conference-wide discussion. Tribal council members and legal interpreters alike set to work on their laptops, pivoting to absorb political trauma at the community level.

Despite rising tension—a ceaseless trickle of Indigenous readers trail Chris throughout each day, in the breakfast line, and as he juggles coffee between stacks of books. All week, it seems, he has signed countless copies of Becoming Little Shell. “I’ve never had so many Natives ask me to sign my book,” he says. “It’s making me a little emotional.”

On the final day, as he rings in the spring equinox with one final sunrise ceremony, all his lessons follow us home—on playing the long game, seeking ceremony within our western world, and remembering that we have all been here before. “We’ve survived so much throughout history,” he closes, as conference attendees set off across the country, past borders both international and reservation-bound. “We’ve survived the mastodons, the dire wolves, and the massacre of buffalo. We came together and have figured it out before. We’ve survived so much. We can do it again.”

“We’ve survived the mastodons, the dire wolves, and the massacre of buffalo. We came together and have figured it out before. We’ve survived so much. We can do it again.”