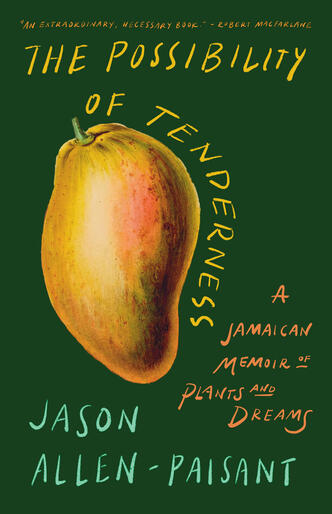

The Possibility of Tenderness: Author Q&A with Jason Allen-Paisant

In anticipation of the release of The Possibility of Tenderness this fall, we sat down with author Jason Allen-Paisant. It was an illuminating and profound conversation with wonderful insight of what is in store in the book.

Milkweed: The title of the book, The Possibility of Tenderness, is such a wonderful and welcoming lead into what the reader will find between its pages. Can you say a bit more about what you mean about tenderness and how the book explores it?

Jason: Racism doesn’t just affect how people are treated—it affects how people experience time. One of its most insidious effects, as Toni Morrison has pointed out, is its ability to trap people in cycles of reaction, whereby they are constantly responding to injustice. This book arises out of anger—how could it not? But I didn’t want it to be about anger. I wanted to claim the right to non-anger, to explore what it means to step outside that constant reaction.

For me, tenderness is a radical stance. It’s a rejection of the idea that Black life must always be framed through suffering and struggle. The book asserts a different way of being—one not defined by the need to explain or prove. That’s why it is called The Possibility of Tenderness. It’s about the right to softness, to presence, to a relationship with the world that isn’t framed by oppression, because we proceed from places that we know intimately to be beyond oppression. We proceed from a lineage of power, from ancient senses of kinship with the earth, with the land.

This kinship has long provided avenues of escape and sites of power—physical, spiritual, metaphysical—for people in the African diaspora, even in the midst of white supremacy’s daily, grinding realities. This is why earth and land are the grounding forces of this book, the guiding thread of its journey. It carries me between England, where I live, and Jamaica, where I return to the legacy of my grandmother—Mama, as she is named in the book. It was she who first taught me attentiveness to the earth, to growing things, to the patience and abundance embedded in land stewardship. That mode of care shaped my creativity, my poetics, and my sense of self.

So while I speak broadly of tenderness in terms of how we care for ourselves, how we practice and insist upon beauty and spiritual lavishness, and how it exists as an inviolable inner surety nourished in the intimacies we protect—the most tangible way tenderness is practiced in this book is through the soil. Through plants, food, and growing things, and our relationships with them. Through the ways they allow us to cultivate life in spite of what seeks to diminish us.

Milkweed: As a deeply personal account of your own relationship with your home in Jamaica and your reconnection with it after reawakening to nature in colonial UK, this book is also a way of reclaiming nature narratives and interrogating who has access to landscapes and nature. Can you say a bit more about what you hope sharing your story might make possible?

Jason: This book challenges the idea that nature writing must be tethered to a white, pastoral tradition. I wanted to show that nature writing doesn’t have to be about idyllic landscapes, untouched by history. It can be about labor, about the people who actually work the land. It can be about history.

One of my aims was to expand what nature writing can look like—to root it in Black and diasporic experiences. It can center peasants, who are often the people most attuned to reciprocity with the earth. It can talk about landscapes that resist romanticisation, landscapes that are not concerned with the romantic gaze. My book offers a version of Jamaica that is not shaped by the tourism industry—the dominant lens through which many outsiders understand the island. Instead, the lands I write about exist beyond the reach of those systems, beyond the capitalist forces that seek to bring them under control.

As I walked the hillsides and mountains in Jamaica, a thought began to settle in my mind: This is what “nature” is to us. That said, I also challenge the term nature itself, because it implies a kind of separation from the earth. The knowledge systems I grew up with never conceived of life outside of our relationship with the land. There was no need for a word that denoted an existence apart from it. In the Jamaica of my upbringing, nature simply did not exist.

So in a nutshell, I wanted my country people—my grung people, my rural mountain people—and all of us who have quieted those connections for years, to see our stories and our histories as legitimate. I wanted to inscribe the grung into literature.

Milkweed: You also are a poet and reference your collection Thinking with Trees in this book. We are so excited to be publishing at the same time and are curious to hear how they might have informed each other.

Jason:The Possibility of Tenderness emerges from the questions I was already grappling with in Thinking with Trees. That said, the expansiveness of literary nonfiction provided the space I needed. The Possibility of Tenderness required room to unfold.

Genre-wise, what nonfiction also offered me was the freedom of storytelling—not that storytelling isn’t possible in poetry, but in prose, it moves differently. It’s more overwhelming, more sustained in its explorations. I hope this doesn’t sound like I’m placing one form above another, because Thinking with Trees still means a great deal to me, even after all this time. To be honest, I’m insanely proud of that work. It was a big grappling, and I’m glad I followed my creative urgings as fully as I did.

But to your question more directly—I recognize, among other things, the connections between time, leisure, and history that I was already wrestling with in Thinking with Trees. That ongoing reckoning with land and time became something I pursued in The Possibility of Tenderness.

A book-length prose project also offers a different kind of space—a space to live with certain key questions, to let them stretch, shift, and work themselves out over time. And I think readers will recognize some threads from Thinking with Trees continuing here—probably more than I even realize. Hopefully, they’ll also see my vision and thinking deepening and evolving in the process.

Milkweed: I was so drawn to how intricately language and stories are tied to the land you grew up on in Jamaica. When writing this book, why did it feel important to also include the lineage and stories of the people, not just the landscape?

Jason: Thank you for noticing that. I have a line in the book that goes something like: as soon as you know land, you know it as a story. That isn’t just a personal conviction—it’s an attempt to put into words a fundamental reality of our relationship with landscape. Perhaps it’s the reality of any people, any community, that shares an intimate connection with its land.

I remember learning some years ago about the songlines—which, incidentally, are also called the dreaming tracks—of the Aboriginal people in Australia and realizing how their sung stories of the land served multiple intertwined functions. These stories are history, memory, and geography all at once—and because they are geography, they are also navigation and orientation. These songlines are obviously distinctive; among the Aborigines, they enable people to travel vast distances while reciting songs about the landscape they are traversing. They map the land not only in physical terms but as a way of expressing intimacy with it.

Likewise, in Coffee Grove and Mount Pleasant, the districts I write about in the May Day Mountains of Jamaica, I feel that stories—stories that mark the land, that function as landmarks, that serve as dot marks on the landscape—are a way of speaking to the land, of saying: I care about you. The ways we express place—through storytelling, through the intertwining of navigation, history, and memory—are ways of holding the land inside us. They are ways of binding ourselves to it. And within them, certainly, is an expression of intimacy.

The storytelling around land is, inevitably, also the storytelling of people. In a place where community is central, belonging to the land often means knowing what happened here and there, knowing the sagas, the legends, the major events that unfolded at specific points on the landscape. In other words, stories form part of an intimate mapping of place.

This book is less interested in the cartographical map than in what I’d call the affective map—the map shaped by feeling, memory, and kinship with the land. It is interested in what the affective map might reveal to us about a place.

Milkweed: Towards the beginning of the book, you talk about “living in another person’s landscape” by both physically living in the UK and through your encounters with the white imagination in literature. Can you say a bit more about how your book pushes against this?

Jason: It does so in different ways. One of them is connected to what I was saying just now—the way the book uncovers a different epistemology of place, of the earth, of plants, etc. So, for instance, I discuss dreams and dreaming in the book, and some may ask, “What does dreaming have to do with ecology, plants and the earth?” Well, in the book I show that in my culture, dreams aren’t just random—they are spaces where knowledge is transmitted. Dreaming is a form of guidance—from the ancestors, but even from plants themselves. A part of the connection that Mama, as well as Congolin (another character in the book), has with plants is through the dream world.

Now, here’s where your point about “the white imagination in literature” also comes in. At first, I found myself explaining this for a Western audience, almost justifying it. But a friend, who read an early draft, said, “Stop doing that. You’re assuming a Western readership. You’re writing in a way that’s defensive, as if you need to prove something.” That was a moment of reckoning. I realized that I needed to fully step into the worldview of the people I was writing about—my people.

Generally speaking, that quote you mention—about “living in another person’s landscape”—is about the urge to embrace the landscape that shaped me, rather than live in someone else’s imagination. But affirming the power and depth and my people’s worldview is also part of that process.