The power of music and verse with stuttering poet JJJJJerome Ellis

“A stutter is an heirloom—something precious, that should be cherished.”

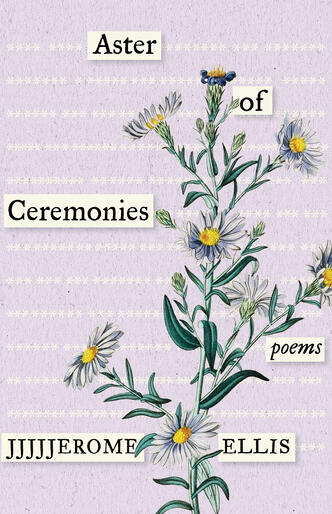

JJJJJerome Ellis inherited his stutter from his mother, who also stutters. They don’t speak often of their shared inheritance but she is supportive of his work. He sees his stutter as an heirloom and his teacher—both in language and in music. He has learned to gracefully accept and even anticipate how it informs his artistic processes of speaking and performing. In his new book, Aster of Ceremonies, he creates a world that blooms backward, reimagining what it means for Black and disabled people to have taken, and to continue to take, their freedom.

On October 7th Milkweed Editions and Liquid Music hosted a multidisciplinary book launch and musical performance to celebrate Aster of Ceremonies. It’s the latest addition to Milkweed Editions’ Multiverse, a literary series devoted to different ways of languaging. The evening’s musical and lyric performance was a unique and singular experience as an event but it can be relived by all via the Aster of Ceremonies audiobook, read and performed by JJJJJerome Ellis. Ellis stood before a rapt audience in a flowing black and white dress with a saxophone slung across his chest. Stage left is an ASL interpreter. In concert with the interpreter, Ellis verbally described his surroundings, his movements, the contents of the slides illuminated on the wall. Projected behind him, lavender lines of poetry from Aster of Ceremonies sit on top of a treble clef music staff. He began the evening by introducing some of his artistic influences: m. nourbese philips’s Zong! and Alison C. Rollins’s “Overkill,” in which Rollins’ declares, “Memory is an art form / forgetting is a science.”

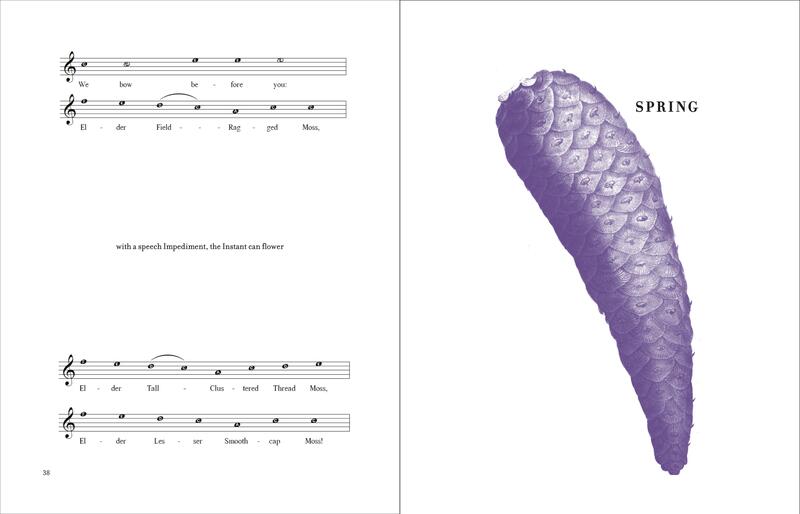

Using archival copy from enslavers’ newspaper advertisements for “run-away slaves,” Ellis created found poetry from them after noticing in their biographical sections frequent mentions of “stoppages,” a term utilized by enslavers to reference stuttering enslaved peoples. In his poems, Ellis liberates the term and reclaims it as something to be savored. Since disabled Black voices are often written out of history, Ellis seized the opportunity to unearth and celebrate those voices. The natural world is omnipresent in Ellis’s work and layered with undulating lyricism praising the flora that captivates him. Ellis shares that “plants make me happy,” and that, “from an early age, the natural world was a way of spending time with living beings,” in safe, judgment-free settings. For his poem “Benediction,” Ellis researched some 1,000 different plant species (he credits his wife, Luísa Black Ellis, a botanist, for conscientiously fact-checking each one) and listed them in litany. He imagined how these very plants were likely the ones escaping enslaved peoples encountered, such as Hannah, an enslaved woman from Charleston, South Carolina, and used them for medicine, food, and shelter along her journey. “We thank all of the Plant Elders for the oxygen she breathes,” Ellis intones. “Elder Mosses, did any of you offer yourselves as a pillow? Thank you.”

Ellis’s verbal delivery is legato and swells in the space of the performance hall—a mix of song and spoken verse. Occasionally, he flows into a stutter and its enjambment sits in the air before delivering the next line with gentle precision. Ellis compares his stutter to “a river that occasionally runs underground before resurfacing.” In an age of minimal attention spans, being able to sit in silence with Ellis’s verse as it submerged for a handful of beats before resurfacing, felt cathartic.

Toward the end of his performance, Ellis left the stage and physically circled the audience playing lingering bass notes on his saxophone. The vibrations danced in my chest and shivers rippled across my skin. Ellis started playing the saxophone at age thirteen, and said music was another source of comfort for him from very early on. “It was a way to express myself with my mouth that didn’t involve speaking, though I do stutter on the saxophone, too […]. It was a great freedom that I felt, and still feel.” JJJJJerome Ellis was joined on stage by neurodiverse poet Chris Martin, the editor and curator of Multiverse. The conversation soon converged upon Ellis’s stutter and how he reckons with it. Ellis opined that when it comes to a conversation, it takes two to stutter—both participants holding equivalent responsibility for carrying it forward. Equally, poetry is an invitation—it takes a poet and the reader to enter into its meaning making, and we invite you to read and listen to JJJJJerome’s work here.