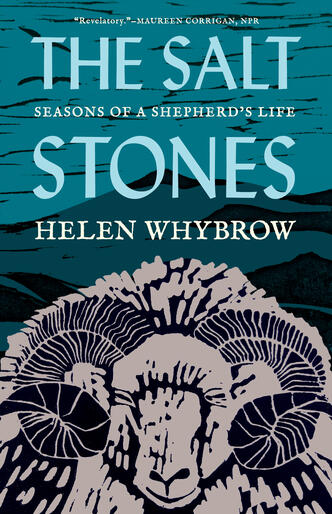

The Salt Stones: Author Q&A with Helen Whybrow

We recently sat down with author (and Milkweed editor-at-large) Helen Whybrow to talk about her forthcoming book, The Salt Stones: Seasons of a Shepherd’s Life. Touching on everything from cycles of life in nature to the art of belonging to parenting on a farm, read on for a taste of what’s to come in this profoundly moving book.

Milkweed Staff: A favorite section from the book is your description of belonging actually being a practice of participation. Can you say a bit more about how that looks as a Shepherd, mother, and activist?

Helen Whybrow: Belonging is something so many of us search for – I know I have, that it’s been a dominant theme in my life. We search for a place or a person or a purpose that helps us feel like we fit, we can be ourselves, we have meaning, we have a home. Belonging is not the same as unconditional love, but it’s closely connected and fundamentally nourishing to our well being. But so often in our modern life, when something or someone doesn’t feel like a fit, we keep searching. We no longer tailor our own clothes. And we rarely live in our clothes long enough that they become molded to our own natural shape. My own journey makes me believe that belonging is something you create by your participation, your curiosity and your deep engagement. It’s not something you find ready made but is shaped by your actions over time. It’s a two-way embrace.

My own journey makes me believe that belonging is something you create by your participation, your curiosity and your deep engagement. It’s not something you find ready made but is shaped by your actions over time. It’s a two-way embrace.

When I got sheep, I began to fully understand this two-way embrace. They forced me to immerse fully in the cycles of life. With each birth and tragic death and all the long days of walking in the field absorbed in weather and seasons and creaturely life, I came to belong on this hillside, a place I wasn’t at all sure I was ready to commit myself to at first. I don’t think I would have if I wasn’t forced to in this elemental way.

MS: I was so struck by how even the snails in the grass contribute to the health of your flock. It really shows just how connected everything is. In that vein, what do you think farming and connection to the land can teach us about community and collective well-being?

HW: Once you really feel that everything is connected– when it gets beyond an intellectual construct and is an embodied way you move through your life – it changes everything. The best way I know how to get there is to take yourself to a place where nature flourishes and start watching closely, and keep doing it in the same place over and over again. In farming, this happens naturally because the work is repetitive, and keeping the land and the flock healthy depend more than anything on your keen observation. But whenever you spend any length of time in nature, you begin to realize that there’s so much going on around us in the more-than-human world that we utterly fail to notice.

This blindness to the natural world starts in childhood; kids always want to poke at the dead bird, see what’s in the mud puddle, crawl into the thicket, and parents tell them no, that’s dirty, that’s dangerous. Our curiosity about the world is squashed early in life. So we need to welcome it back. It’s hard not to want to protect the integrity of a natural place once we have felt its full pulse and beauty and dynamic aliveness. It becomes imperative to protect it because it begins to feel like an extension of ourselves, which it is. We belong there. Similarly with people; it’s hard not to want to look out for people and their rights – all people – once you take the time to get to know them.

Our curiosity about the world is squashed early in life. So we need to welcome it back. It’s hard not to want to protect the integrity of a natural place once we have felt its full pulse and beauty and dynamic aliveness. It becomes imperative to protect it because it begins to feel like an extension of ourselves, which it is. We belong there.

MS: Time moves in such an interesting way in this book. You welcome us into the seasons of the farm but also reference the past and future through your matrilineal line with your mother and daughter. Can you say a bit more about how this expansive way of looking at time connects all the threads in your book and life?

HW: Thank you for noticing that. I think about time a lot. I wrote the book as one full seasonal year, beginning and ending with spring, but it covers twenty years of my life. Living by the repetitive tasks of the seasons on a farm makes you understand time as a circle, or a spiral, moving forward but at the same time circling and repeating and accruing meaning. I think of time as the layers of leaves that break down into soil on the forest floor; they fade, but they become something else that nourishes what will come in the future. There may be no such thing as living in the present – we are constantly living in multiple dimensions of time.

Living by the repetitive tasks of the seasons on a farm makes you understand time as a circle, or a spiral, moving forward but at the same time circling and repeating and accruing meaning.

As my mother’s dementia took over, I noticed how precious memory is, but also how memory is not only held in the mind but also in the body, and how important it is to learn how to do things with our hands and our movement through space, creating those nerve pathways that will possibly serve us longer than anything else. This is another reason why holding onto a pastoral or agrarian life is so important I think, because it gives a place for elders, who can feel competent and useful with tasks their bodies have always known how to do.

My mother died while this book was in production, and I discovered how my own study and writing of my mother, my intimacy with how she did things and the small joys she constantly noticed and celebrated, had become part of my own wiring. I was not only carrying memories of her, I was extending her loves and habits and temperament into the present, keeping her alive through me. The stories we pass on of grandparents through grandchildren and beyond are key to how we understand ourselves, and the same is true for how we understand nature. There is all kinds of traditional ecological knowledge that is being lost because we don’t keep it alive through our practices on the land, and in that way the land itself is losing its memory. Shepherding is a practice of remembering.

There is all kinds of traditional ecological knowledge that is being lost because we don’t keep it alive through our practices on the land, and in that way the land itself is losing its memory. Shepherding is a practice of remembering.

MS: If there is one thing about the experience of being a shepherd you hope your reader will take away from the book what would you want it to be?

HW: Toward the end of the book I write about shepherd’s mind, a phrase that came to me one day when I was trying to understand how the way I live on the land has changed the way I think about everything. What I mean by shepherd’s mind is to gather information by observing and by bravely accepting everything that comes into your expanded field of awareness, not acting on cultural norms or information you’ve been given that’s not rooted in your reality. My advice would be: Get a lot of experiential miles in the study of something you love under your belt, really watch, deeply listen, and then trust your intuition.

What I mean by shepherd’s mind is to gather information by observing and by bravely accepting everything that comes into your expanded field of awareness, not acting on cultural norms or information you’ve been given that’s not rooted in your reality.

MS: Can you tell us a little more about your daughter, Wren’s involvement on the farm and in the creation of this book? Do you have any insights on what it means to raise a child in such an interconnected way to the land?

HW: Thank you. This is the perfect question to end with because it brings us back to where we began, with belonging being something you create through participation and engagement, through falling in love. A child wants to feel competent and involved, included. One of the treasures of my life and of a farming life is that children can see and feel and contribute to what makes up their parents’ days. It can make sense to them. From a very young age we taught and trusted Wren to do things on the farm. She was washing eggs and chopping veggies with a sharp knife when she was so small she had to sit on the counter to reach the sink. She was feeding the chickens when she was still in diapers.

All the ways in which I had included her in my farming from the day she was born—strapped to my chest as I delivered lambs—made it natural for me to also include her in my writing process. I gave her the chapters to read and suggested she make some art – entirely her own interpretation – for each one. She has always made a lot of art, and been surrounded by creative people. Her art has a sincere raw quality to it that comes from a place of believing there is no one right way to draw or to be. I feel proud that I helped instill that sense of creative freedom in her. Wren is 20 now, and in her life, again I see how time is cyclical. Her deep attachment to our farm is like mine was to my childhood farm, and as a young woman she struggles with the conflict between the desire to stay on the beloved land where she was born and the longing to explore, as well as the great cultural pressure young people feel to leave home, just as I did. She has a deep love and comfort in nature as well as with people from all walks of life from having grown up at a center for activists. That’s a privilege and a gift. Now she just has to trust that she can carry her sense of belonging with her.

Publishing in June 2025, you can preorder your copy of The Salt Stones by Helen Whybrow here.