Voicing grief: the language of elegy

By Melissa Kwasny

One of the first things I learned as a hospice volunteer is to think of death not as a medical emergency but rather as a spiritual event. After attending many deaths, including that of both my parents, I have learned something else: dying is a spiritual process, not a moment. It is a process not only for the person experiencing it but also for their loved ones who are left with grief.

Grief is universal. All peoples, and most animals, experience it. It is, paradoxically, also individual. We each suffer grief uniquely. It is perhaps our most dangerous emotion. People really do die of grief. That is why we have so many rituals and ceremonies around it. It is why certain cultures—I’m thinking of the Irish and those in India—hire keeners or professional mourners to relieve some of the strain by sharing it. Yet grief is a private emotion, and one of the most difficult to describe to others.

Poetry gives us a language to do this. It is called the elegy.

Peter Sacks, in The English Elegy: Studies in the Genre from Spenser to Yeats, writes that the English elegy has its roots in Greek funerary rituals and rites, lamentations for the dead written in hexameter couplets sung and accompanied by music. By the 16th century, the English elegy became a mix of tribute, lament, question—usually of one’s faith—and sometimes curse. We recognize these responses in what Freud called “the work of mourning.” Most elegies actually enact this work, moving through anger, sadness, and questioning to, hopefully, some kind of consolation or acceptance.

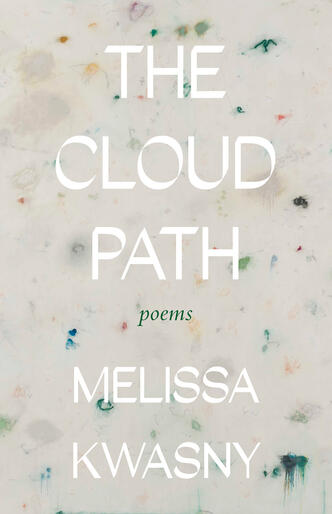

My seventh book of poetry, The Cloud Path, is elegiac. The poems speak about my mother’s dying, the caregiving, the hospice protocols, the subsequent grief, and the possibilities of consolation I discovered. It is also about the grief many of us share for the earth: the loss of beloved landscapes and weather patterns, and animal and plant extinctions. The cloud path, after all, is the path all beings walk on earth, a path that is temporary, temporal, and always life-changing.

Sacks says that contemporary American elegies depart from traditional elegies by rejecting or radically transforming certain conventions. Gone often are the pastoral myths and funerary rituals. The mourners (or chorus) have been “exiled.” The public figures that were the subject of well-known elegies—Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed” for Abraham Lincoln; Shelley’s “Adonais” for John Keats, Auden’s “In Memory of W.B. Yeats,” to name a few—are joined by ordinary and less public figures—mothers, friends, lovers. There are elegies for one’s people—M.L. Smoker’s “Book of the Missing, Murdered and Indigenous” and Mark Doty’s “Tiara,” a poem about a friend who died of AIDS, come to mind.

There are certain conventions of the elegy that survive in many contemporary poems. Tribute, certainly; certainly lament. In The Cloud Path, I detail some of them in a poem titled simply “Elegy”:

They say an elegy should include a catalog of flowers,

a cast of mourners, repetition of the deceased’s name, anger

and accusation, though performed in a measured pace,

one that follows the progressive drama of the seasonal gods.

In the writing of the poem, I found myself including most of them, asking a myriad of questions— “Must [death] always be like hers was, a dark hallway strewn / with broken glass. Can the scene ever be swept of dread?”—accusing my father and the “pine-winds,” including the bouquets my mother’s friends brought her from their kitchen gardens.

In his book Dominion of the Dead, Robert Pogue Harrison claims that the very definition of being human is to be bound up with humus, the earth, which accordingly means to be bound to the dead who have been buried there. “To be human,” he writes, “means to come after those who came before.” Our very idea of place, or home, he speculates, might have originated in our need to know where our dead are buried, citing evidence that burial sites have been found that pre-date our first human dwellings. We house our dead, first, in the earth, and then keep them alive in our homes, in our memories, our stories, and in our very language. In other words, it is our job to keep the dead alive.