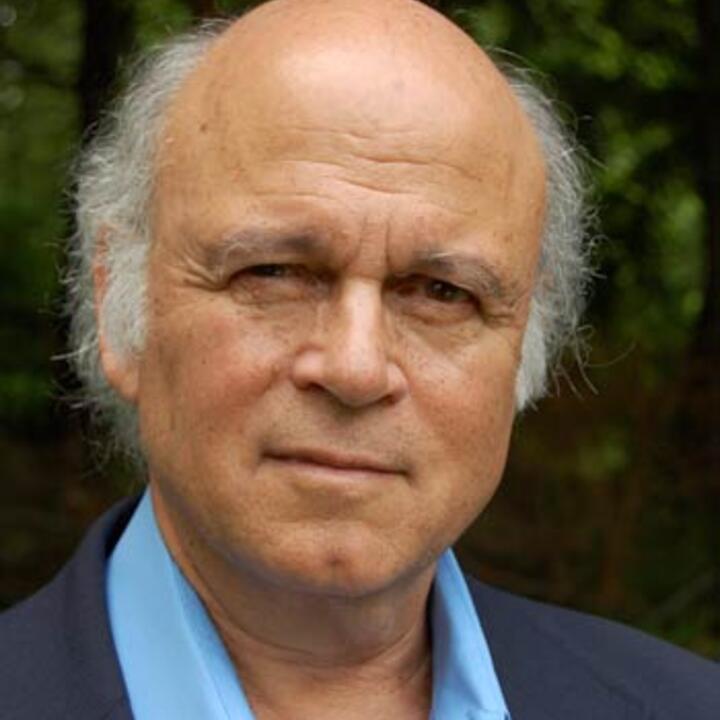

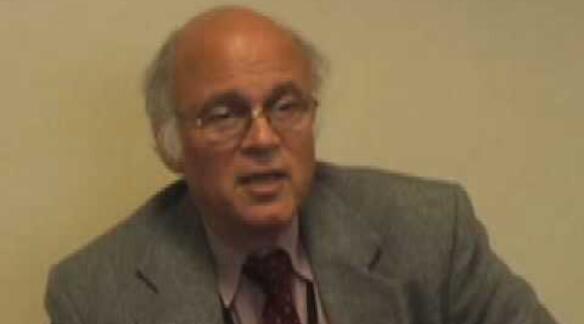

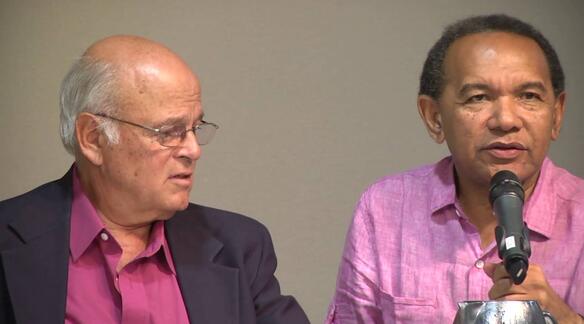

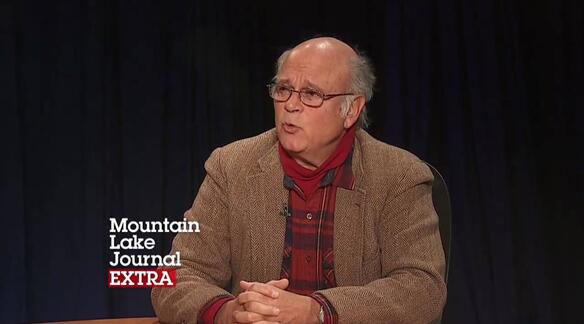

Alexis Levitin has translated over thirty collections of Portugese poetry and prose into English, including Rosa Alice Branco’s Cattle of the Lord, Salgado Maranhão’s Blood of the Sun, Clarice Lispector’s Soulstorm, Eugénio de Andrade Forbidden Words. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Fulbright Commission, the Witter Bynner Foundation, the Gulbenkian Foundation, and Columbia University’s Translation Center, which awarded him the Fernando Pessoa Prize. As a translator, he has benefitted from residencies at the Banff International Translation Centre in Canada, the European Translators Collegium in Germany, and the Rockefeller Foundation’s Study and Conference Center at Bellagio, Italy. A Distinguished Professor at SUNY Plattsburgh, he has given readings and lectures on translation at well over one hundred colleges and universities in the USA, as well as institutions in Brazil, Portugal, Ecuador, the Czech Republic and France.