5 Reasons to Teach This Book—21|19: Contemporary Poets in the Nineteenth Century Archive

Welcome to 5 Reasons to Teach This Book! In this new interview series, I’ll be investigating and straight-up admiring some of Milkweed’s titles via conversations with educators, authors and booksellers. We’ll get down to the nuts-and-bolts of anthologies as well as some exciting pedagogical takes that will make your students want to steal this book from you. While the title of this series is prescriptive, we hope that your engagement with the dialogue is organic and that you find entry points into the texts that align with your goals as a teacher, reader, writer, or literary advocate.

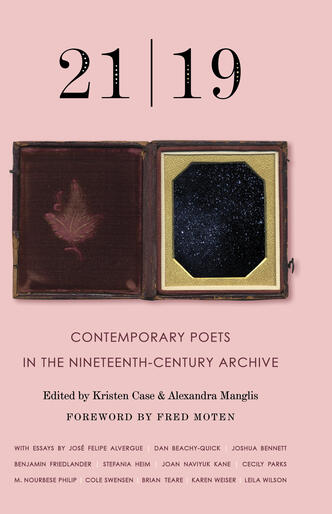

As the dregs of summer transition into Hot Nerd Fall and with syllabi rustling across the nation like the soon-changing leaves, we look back—as Fall often demands—to memory and to the archive. In that spirit, I interviewed Kristen Case and Alexandra Manglis, editors of 21|19: Contemporary Poets in the Nineteenth Century Archive (published this August), an anthology of muscular and innovative prose where contemporary poets such as Joshua Bennett, Cole Swensen, and Joan Naviyuk Kane—among other contemporary superheroes—wrestle, challenge and question the nineteenth century archive of Whitman, Dickinson, Poe, Eliot and many more. We also spoke about vulnerability, apocalypse, and the function of the archive—read on for more.

Julian Randall: There’s a lot to unpack in the foreword by Fred Moten but I think most prominent for me was this quote: “Can there be a renaissance that isn’t forged in vulgar imposition and forgetfulness of this radical inescapability?” As I read the foreword, I realized that Moten attaches this question not only to land but also to creative approach. We talk a lot about ideal readers but maybe less than we should about ideal lands, so what is the land (and with it, possible lives and renaissances) you hope this collection seeds?

Kristen Case: I hope the book fills people with a sense of permission. Permission to trespass, to cross boundaries, to disrupt, to enter the archive, to leave traces, to feel things. I hope that people feel exhilarated by the kinds of freedom that the writers in this anthology are practicing and that it expands their own practices of freedom and deepens their drive to extend freedom to others. That sounds embarrassingly idealistic, but there it is.

Alexandra Manglis: Following that vein of embarrassing idealism, my hope is that the collection seeds a land conscious of its trouble. In other words, what can a land look like where forgetfulness is not an option, even as memories and archives serve us imperfectly? How can leaning into the discomforts of history offer a sense of a living, active community that is cohesive even as it is fractured? These questions are too big for one anthology to answer, but I hope that 21|19 can offer through-roads towards those answers.

JR: In your introduction you mention that each essay within the anthology is characterized by an “affective openness.” I’m curious what the metric (if one exists) is for openness and how you find those qualities in essays. For instance, is it a temporal or emotional or intellectual consideration or some composite of how the three populate the essay in harmony? How do you see the opennesses in this collection working together and how did this affect your choices on ordering the essays?

KC: For me, one of the most meaningful aspects of this anthology is its range of feeling. Somewhere Charles Bernstein writes of the “narrow affective envelope of sobriety, neutrality, objectivity, authoritativeness, or deanimated abstraction” in which most academic essays are written. I feel suffocated in that envelope; I think thinking is suffocated in that envelope. Part of what we wanted to do was see what kind of thinking could happen when we explicitly told contributors that the whole affective range was open to them: that their writing could partake in rage, grief, love, bewilderment, etc.

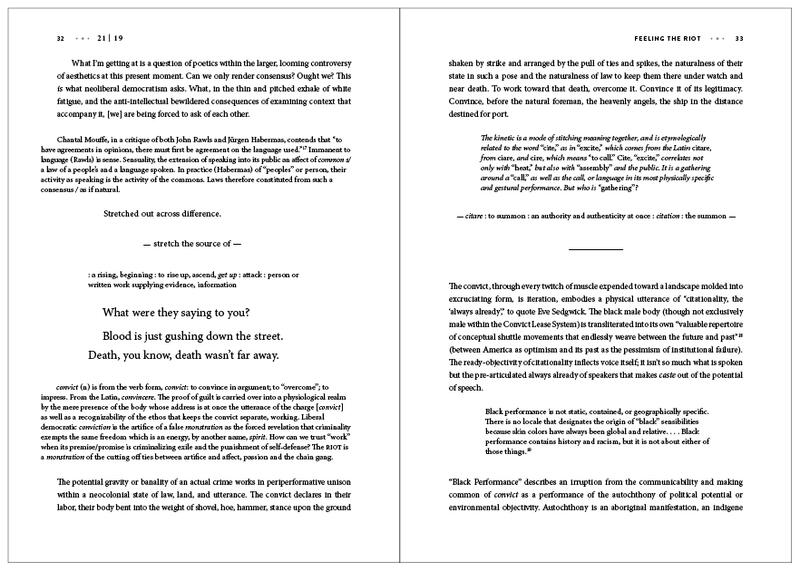

AM: I think “affective openness” can also be a way of saying “vulnerable” and some of the essays that started to come into our email inboxes had incredibly vulnerable moments in them. I’m thinking of Karen Weiser’s piece on Poe, horror, racism, and mass shootings. The pain and violence and anger that imbues José Felipe Alvergue’s piece “Feeling the Riot.” The everyday moment in the kitchen where Joan Naviyuk Kane describes sitting with her children discussing language. This isn’t a book that must be read in a particular order by any means, but if one were to follow the given order we’ve chosen I would like to think that it gives the reader room to breathe from one essay to the next, that it compiles these moments of vulnerability mindfully, and that the reader notices how the first and last essays are purposefully chosen to bring them literally back down to earth, to our shared ground.

JR: I’m thinking a bit about how some of these essays were previously published and some were not, and I’m wondering at more of a nuts-and-bolts level how this anthology came together at an author level. In knowing that some of these essays had had public lives before, were you seeking out specific writers and thinkers to help fill in the landscape or was the process a little more organic?

KC: The process was more organic. We wanted polyvocality and inclusion. We wanted poets at different stages in their careers. And we wanted poets whose writing we deeply admired. Those constraints were pretty absolute. But then we trusted that, if we chose our contributors carefully and trusted their voices, the book would find a shape, and it did. We didn’t set out to make this particular book: we made it as we went, working with what the contributors gave us.

AM: We approached all the poets about contributing before they had published their work in other venues—sometimes before they even knew they would be publishing in other venues. And I think they all showed us drafts of essays before they were published elsewhere, so we began to get a sense of where the collection was going from quite early on. This collection has been a five-year project in the making, with many, many drafts and iterations.

JR: One essay I particularly admired in its public life and was grateful to see expanded and anthologized is Joshua Bennett’s “Revising The Waste Land.” The scope of the essay is truly wild, covering Phillip B. Williams, James Monroe Whitfield, Public Enemy, Toni Morrison, and Margaret Garner—all against the backdrop of Kea Tawana’s Newark Ark, where both the images and the narrative are stark and haunting. In all of this, the line I can’t get out of my head is when Bennett writes, “We desire the end of the world because of a black love that demands such radical dreams.” At the end of the world what do you see as the function of the archive? What do you see as our obligation as writers and educators to the archive after the world it recorded concludes?

KC: The paradox there is that the archive, like the kind of apocalypse Bennett describes, assumes some kind of continuance, some new form of life. I don’t think so much about what we owe the archive but rather what we owe that future life, which is, I think, everything. I think of the archive as a kind of seed vault: it’s exactly for the “end of the world” that we need it—to hold traces of other forms of life, to preserve possible forms of life, of feeling and being and thinking.

AM: I love this question and I think that we are, in many ways, always already living the apocalypse—in our current moment we feel this most strongly through irreversible climate change. I’m in firm agreement with Kristen that archives are like seed vaults. In the collection’s final essay, Leila Wilson writes, “As I disintegrate, Whitman expands my kin.” I think therein lies our obligation to the archive: to leave things behind so that kin, family, [and] community may expand from them.

JR: There’s tremendous aesthetic variance between the writers in the collection and as a budding nonfiction writer myself I was stunned and delighted to learn of more things essays can do. I find this has something to do with received limits of language and print that this anthology sometimes pushes and nudges outward. After editing this collection what’s one thing that you found language doing that you wish it did more often?

KC: What a great question. To choose just one thing among many: I love how material the words in some of these essays feel. In Stefania Heim’s essay [“Essay in Fragments, A Pile of Limbs”], for example, I am absolutely floored, every time, by the effect of those beautiful archival scraps with their ink and (possible) blood stains, but also her careful rendering (and the typesetter’s careful reproduction of her rendering) of the pencil marks in the manuscripts. There are a few moments in the book that just feel magical for me in this way, that dissolve my sense of temporal distance and put me in curious touch with the dead and with language.

AM: I can’t wait to read your nonfiction! To answer your question, we were very clear in our brief that we wanted these essays to take on whatever form the writers needed or wanted. In large part because we wanted to see that variance sitting side-by-side in one book, and we are incredibly grateful to Milkweed and the typesetters for having the patience for such a stylistically mercurial book. Recently, I have been thinking about M. NourbeSe Philip’s piece [“Making Black Cake in Combustible Spaces”], which revisits a story she wrote and published and places it into a new context and conversation. Ben Friedlander does something similar in his essay [“Homage to Bayard Taylor”]. I love that we can go back to our old work and bring it into the present again, with all the regrets attached but still find value in it. So often what we create is meant to be finished and then left behind to become ossified, as though we aren’t allowed to play with it again. But where is the joy in that? Seeing NourbeSe and Ben’s work has me feeling less restricted about language’s temporal limitations, and has given me permission to revisit my own work more freely.