5 Reasons to Teach This Book: Wound from the Mouth of a Wound

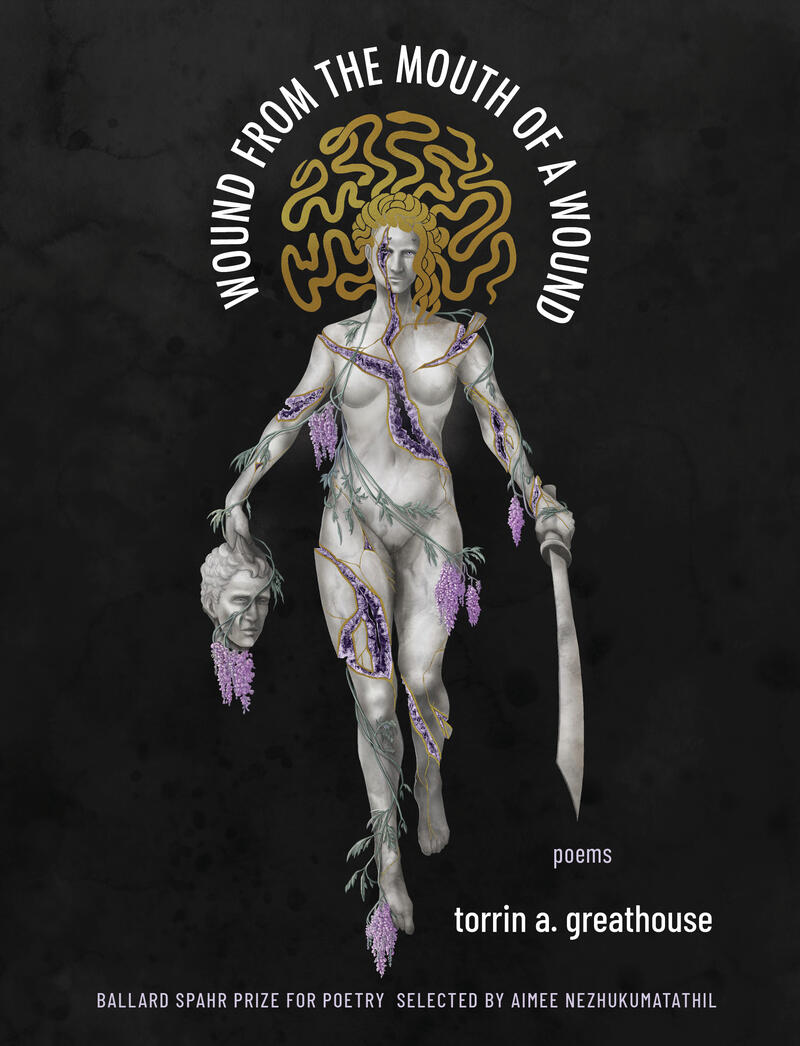

Welcome, friends, to the latest installment of 5 Reasons to Teach This Book! In this interview series, we examine what we can learn from Milkweed’s titles by discussing our books with educators, authors, and booksellers. This month, we’re featuring the 2020 Ballard Spahr Prize for Poetry winner, torrin a. greathouse and her debut full-length collection of poetry, Wound from the Mouth of a Wound.

Wound from the Mouth of a Wound is a deftly transformative text—one that resonates with prosodic brilliance. torrin’s formal variety is electric enough on its own, but combined with her stinging imagery and unreserved depictions of disability, physical illness, and gender nonconformity—well, this book crackles with classroom potential. Read on to hear more from torrin about poetic craft, hybridity, metaphor, and methods for “[subverting] cultural and institutional linguistic violences.”

Bailey Hutchinson: Wound from the Mouth of the Wound stuns me with its craft. Mirror sonnets, burning haibun, essay fragments—the book is peppered with paradigm-defying forms. Can you tell us a bit about your relationship with poetic form?

torrin a. greathouse: I’ve always conceptualized my relationship to form through the framework of embodied poetics. I write from within a body, both disabled and trans, that’s often misrepresented—when it’s represented at all. Bodies like mine are rendered as either metaphor or convenient narrative trope, within mainstream poetry. Meanwhile, so much of the received vocabulary we have for discussing the form of a poem is the language of the body: a body of work, or the body of a poem; muscular syntax; the poet’s voice, their breath; enjambment, drawn from the French “jambe” meaning leg; a metrical foot, for example the iamb, with its name tracing back to a word meaning a cripple.

If the poem—through all its component parts—forms a body, then I am most interested in constructing forms that resemble my own disabled trans body-mind. My body’s existence is defined by others through its fractures and dissonances, as well as the ways in which they fail to see me as legible. Each of the invented forms you noted within the collection takes a received form (sonnet, haibun, and scholarly essay) and infuses it with the same kind of fracture, or steps into a mode of illegibility, demanding that an assumed cisgender, heterosexual, abled, will have to engage in deconstructing their preconceived notions of poetic craft to enter these poems.

BH: Much about your work makes me think of genre-crossing, or writing beyond genre—particularly the Essay Fragments. Did you envision each Essay Fragment as it is, or did they begin as something else?

tag: Hybridity, in both logic and mechanics, is deeply important to my work. Even when it isn’t clearly identifiable on the page, my formal approaches have been shaped by disability studies, quantum mechanics, trauma psychology, folklore, & mythology.

In their earliest form, the poems you mentioned were conceptualized as self-portraits. The self-portrait is, of course, another crossing of genre, the visual object—real or unreal—rendered in text. However, it is a form so commonly interpolated into poetry that we rarely think of it in this way. Initially, the mode of portraiture served to help superimpose my own narrative on the various cultural models of disability the poems explored, but as I edited, the concept of rendering them as fragmented journal essays emerged, which allowed me to more closely hone the discursive elements of the poems. In a way, I began these poems by marrying two vastly different elements, a visual-cum-textual rendering of the body and a cultural conceptualization of disability, and had to pull back toward a less distant form of hybridity to find the form that suited the poem best.

BH: Another thing I’m struck by in your work is your imagery: the “slim hips a garland of cardinals” in “Aquagenic Urticaria,” a “[plum] plummeting against cement” in “Still Life with Bedsores,” a “throat wrapped in a necklace of rope” in “When My Brother Makes a Joke About Trans Panic.” Though frequently rooted in the body, your imagery so often sprouts into beyond the body—could you speak to your image-making process?

tag: All images for me begin in the mechanism of metaphor, which I like to frame to my students as a form of linguistic engineering. The example I typically use is a bridge, stretched out between two points—the tenor and the vehicle. I remember riding, as a child, in my parents’ car high over the Puget Sound, as we crossed the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Its creaking cables stretched out 5,400 ft., almost 200 ft. above the water, and that day a fog had rolled in so heavy that the road was swallowed ahead of us.

I spent the drive gripping my seat, convinced we would topple into the water below, until the sudden green of the coast split the endless gray. When I begin to create an image, this memory often guides me. Reminds me to construct a distance between the tenor and vehicle great enough that a reader may, for a moment, lose their destination, and experience the wonder of reaching it suddenly without having toppled into the water below.

BH: Your poems often take discipline-specific language to task for its failure to serve everyone who uses it and is affected by it (I’m thinking particularly of “When My Gender is First Named Disorder”). What guidance do you have for writers attempting to find (or invent) language that works on their behalf?

tag: In the title poem of her collection Look, Solmaz Sharif writes “Let it matter what we call a thing.” Language is one of our oldest, and most versatile, human technologies. A technology that is unfortunately profoundly capable of violence, particularly a settler-colonial language like English. A language where balm sounds so much like bomb.

When working toward reconstructing or inventing poetic language to subvert cultural and institutional linguistic violences, I begin through history. I trace the etymologies and common usages of language to unravel the ways in which it has gathered blood over time. Uncovering these histories, or rewriting them, is one way I have found to take power away from those two might use language for oppressive means, and to take it into my own hands.

BH: What books or other types of media would you include on a syllabus featuring Wound from the Mouth of a Wound?

tag: If I could put together a dream syllabus of texts which fed and inspired Wound from the Mouth of a Wound, it might look something like this:

Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability

Kay Ulanday Barrett, When the Chant Comes

sam sax, Madness

Jillian Weise, The Amputee’s Guide to Sex

Joshua Jennifer Espinoza, There Should Be Flowers

Jim Ferris, “The Enjambed Body: A Step Toward a Crippled Poetics”

Danez Smith, Don’t Call Us Dead

Ocean Vuong, Night Sky With Exit Wounds

George Abraham, Birthright

Sam Rush, Swallow

Against Me!’s album Transgender Dysphoria Blues