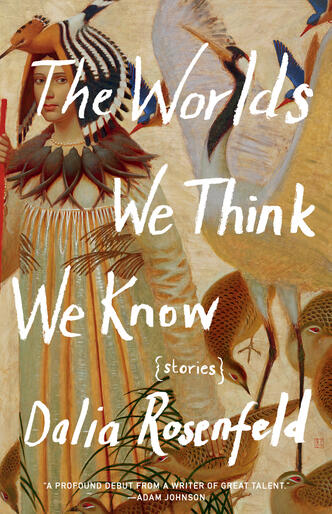

A Conversation with Dalia Rosenfeld

I received The Worlds We Think We Know on submission a few years ago, before I joined the staff at Milkweed, while I was working for another publishing house in New York. I thought the stories were wonderful: dreamlike and wry and sometimes sad, in a way that felt very grounded in a few different literary traditions but also somehow universal. Unfortunately they simply wouldn’t have been the right fit for a house that didn’t publish debut story collections, and I had to let them go.

But Dalia’s work stayed with me, and once I landed at Milkweed—where we do have the flexibility to take risks on work commercial publishers sometimes can’t—I got back in touch with the agent right away. I’m so happy we’re able to support writers like Dalia and stories like these. I sat down to talk with her before her recent book launch in Minneapolis.

Joey McGarvey: This is your first book! Do you know how long have you been working on these stories?

Dalia Rosenfeld: The first story I wrote probably dates back fifteen years. The whole collection was a long process. It’s been with me for over a decade, and each story feels like a child, like a family, and that family keeps expanding and growing in different ways. Eventually I realized I had enough for a book. But I was also ready to start a new project and move on to different themes.

JMG: Do you see certain themes woven throughout the collection?

DR: The more I talk about the book, the more commonalities I see between the stories. There’s a sense of displacement the characters feel, a sense of uprootedness. They’re given chances to reinvent themselves, which they regularly squander in ways that leave them a little bewildered and bemused—states of being which, while not redemptive, often lend themselves to irony and humor. They’re not loners, but they’re lonely. They’re not drifters, but they drift. For example, Misha in “Swan Street” moves to America to fulfill the American dream, but then stays put in a bed and breakfast and refuses to leave. These contradictions exist in us all.

JMG: When I read the book on submission (both times!) I was particularly struck by the recurring motifs: lemons, accordions, the piano. How did you gravitate toward those images and symbols?

DR: It never fails to amaze me that I’m living in Israel now, with a lemon or date tree on every corner, things I didn’t grow up with in Indiana. They’re such potent symbols, symbols of untouched, ideal places. Modern Arcadias. Not just visually—when they bloom, they take your breath away. Suddenly I live in this country where I’m connected to nature in a new, visceral way.

Music has always been a big part of my life. I grew up in Bloomington, Indiana, which has a world-famous music school. Many of my piano teachers were protégés of famous musicians. My former husband took up the accordion with great passion, and I admired and observed this passion from a distance. There was something there that was very personal, off limits, that I couldn’t access. I associate the accordion with certain longings, so it naturally found its way into my stories. And it’s ever-present in klezmer ensembles, so it also has a Jewish association for me.

Sometimes symbols or images will generate an idea for a story, but not always. “Swan Street,” again, which is about a Russian moving to America, started from a chance encounter I had. In Boston, I met a Jewish immigrant from Russia, and he seemed so alone and perplexed, as if he had woken up that morning to find himself transplanted to a different country. I asked him where he was settling in, and it was a bed and breakfast. He’d been there for months. That encounter led to me imagining his story.

JMG: Sometimes your characters feel more at home in books than in the real world. What is the role of reading in your own life, and which writers do you admire?

DR: Growing up, I was always a very uneven reader. My dad was an English professor and a scholar of Holocaust literature. Books about the Holocaust populated our home, and those were the books I read. That period of history shaped my identity in a substantive, haunting way. Because my dad taught the American Jewish writers, I also grew up with Philip Roth and Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud and Cynthia Ozick. Later I discovered (on a different shelf) Kafka and Nabokov, I.B. Singer, Bruno Schultz, Max Frisch, W.G. Sebald, and still later (on other people’s shelves) Jamaica Kincaid, Rivka Galchen, Nicole Krauss, Miranda July…

JMG: The stories in this collection are largely set in places you’ve lived: Charlottesville, Oberlin, Tel Aviv. I’m curious to hear how those places shape your characters.

DR: I think the characters, no matter where they are, find themselves feeling disjointed or disoriented, but not alienated. They always suspect there’s the potential to feel at home—they just have to seek the right formula and find the right people. And so they move between places, not simply geographically or physically, but sometimes just from the confines of their own bedrooms.

There’s a certain laziness in some of them. They want to engage with the world, but they’re not willing to fully do the work. They’re dreamers, instilled with a kind of comic innocence. They can be impulsive, acting on instinct and intuition, lacking self-awareness. It’s something that’s endearing; I’m not writing satire. The characters are aware of their own failings, and I try to inject humor into what might otherwise be seen as horrible situations. And they’re resilient: my characters pick themselves up again and start over.